Main Text

Charles Joseph Epstein, M.D., died on February 15, 2011, at the age of 77, after a year-long battle with pancreatic cancer. Charlie had a remarkable career as a scientist, clinician, educator, and leader in the human and medical genetics community. Charlie was the recipient of the two major awards of The American Society of Human Genetics (ASHG) in addition to serving as its President (1996) and as the editor of The American Journal of Human Genetics (AJHG), the Society's journal, for seven years (1987–1993). His impact and influence was immense, and he will be greatly missed.

Charlie grew up in Philadelphia, where his Ukrainian Jewish parents settled after separately immigrating to the United States in 1921. He was the second of three sons and grew up in an environment that was loving and supportive but demanding. There was a strong devotion to family, and the Epstein brothers remained close throughout their lives. Excellence was expected, and Charlie did not disappoint, nor did his two brothers, Herbert (older) and Edwin (younger); all being accomplished scholars.

Charlie's Hebrew name was Bezalel Joseph. Sometimes an individual's life reflects that of his namesake, but in this case the correspondence is truly remarkable. In the Bible, Bezalel was a talented builder and architect of the Tabernacle, and Joseph was known for his strong and courageous leadership. Charlie embodied both, bringing talent, creativity, and heart to everything he built and led.

Charlie's skill and ability manifested themselves early. In addition to excelling in school, he built model airplanes, ships, and crystal radios with precision. He played the cello. He was an eagle scout. He ran track; his event, the 440 yard dash, requires a perfect balance of speed and endurance. And his thirst for knowledge never ceased. He would continue to have broad scholarly and extracurricular activities throughout his life.

Charlie also had an independent streak. In addition to choosing cello over the expected piano, Charlie decided to attend Harvard College rather than the University of Pennsylvania, even though both his brothers attended Penn, the local Ivy League school. His move to Boston was enabled by receipt of a coveted Harvard scholarship, and he enthusiastically went to Boston. This decision was quite fortuitous, however, because soon after arriving at Harvard, Charlie met Lois Barth, a Radcliffe student who would become his life partner. Charlie excelled as a chemistry concentrator at Harvard and graduated summa cum laude. He and Lois then attended Harvard Medical School together, where Charlie graduated first in his class and magna cum laude. Charlie then did a residency in internal medicine and pathology, while Lois did one year of pathology at Brigham and Women's Hospital followed by a year of internship in internal medicine at New England Center Hospital.

As detailed in his Allen Award address,1 Charlie took a somewhat unusual path into the field of genetics. He decided to pursue laboratory work at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) with Christian Anfinsen on protein structure and function. In particular, Anfinsen was pursuing the idea that the 3D structure of a protein is determined by its amino acid sequence, and he won the Nobel prize for proving this theory. Charlie was given the task of denaturing and then refolding trypsin. Charlie felt that his time in the Anfinsen lab fostered his independence in research because Anfinsen left for a prolonged trip soon after Charlie's arrival. Charlie was able to make his own decisions about his research directions and approaches that allowed him to grow as an independent scientist, but he also knew that he did not want to become a protein chemist. This was also the time when molecular genetics was blossoming, and Charlie's work in the Anfinsen lab underscored the importance of genetics in understanding protein structure and function in health and disease. To be oriented in the nascent field of medical genetics and obtain clinical genetics training, Charlie went to the University of Washington in Seattle with one of us (A.M.). Seattle had one of the few programs providing such training. He studied Werner syndrome, the beginning of a life-long interest in aging. He returned to the NIH as a postdoctoral fellow after his Seattle stay, and his interest in medical genetics was fostered by attendance at half-day genetics conferences led by Victor McKusick at Johns Hopkins.2

Charlie and Lois then moved to the Department of Pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine in 1967, and they spent their entire academic careers there (Lois was based in the Cancer Research Institute). Charlie was hired as the first Chief of the UCSF Division of Medical Genetics in the Department of Pediatrics, one of the first divisions of medical genetics in the nation. He led this division for 40 years. He established a model genetics clinic and prenatal genetics services as well as satellite clinics to provide care to the Bay Area and much of Northern California. For years, Charlie led the Program in Human Genetics at UCSF and was a leading force in the formation of the Institute for Human Genetics at UCSF, recruiting one of us (N.R.) as the first director. This institute now has more than 60 faculty and celebrated its fifth anniversary this past year. Outside of UCSF, Charlie had a major influence on another Bay Area scientific institute, the Buck Institute for Research on Aging, serving on its scientific advisory board and the board of trustees for many years (Figure 1). Thus, Charlie's impact on the scientific and medical community of UCSF and the greater Bay Area was immense.

Figure 1.

Portrait of Charles Joseph Epstein

Charles J. Epstein, portrait taken in 2009. Photo courtesy of the Buck Institute.

Charlie was the consummate physician-scientist. His major research interests were in the genetics of early embryonic development, the pathogenesis of Down syndrome, genetic approaches to the study of free radical defense mechanisms, and aging.1 He authored over 300 peer-reviewed articles, more than 150 reviews and chapters, and several books. He first decided to use the mouse model when starting his own lab to study early preimplantation mouse development and made important discoveries regarding the timing of initiation of X chromosome inactivation. These studies convinced him of the power of using a mammalian model such as the mouse for studying problems important for understanding human genetic diseases. Charlie was always thinking (and writing) about mechanisms that cause birth defects, and his original ideas were influential. Two examples stand out. First, Charlie hypothesized that the abnormalities found in Down syndrome were due to an increased dosage of critical genes on chromosome 21. This was not the favored model at the time. One of the first genes identified on human chromosome 21 was the interferon-alpha receptor gene (IFNAR1). This was a fortuitous coincidence because Lois (who was also a scientific colleague and collaborator) was an international expert on interferon. So Lois and Charlie set out to study the binding of interferon to euploid and trisomy 21 cells. They found that 50% more interferon bound to trisomic cells than euploid cells, and the trisomy 21 cells were as much as 10 times more sensitive to the effects of interferon. Similar studies were performed to identify mouse chromosome 16 as a partial homologue for human chromosome 21. To further support this model, Charlie studied mice with partial trisomies for regions of the mouse chromosomes homologous to human 21, thus producing the first mouse model of Down syndrome. The findings resulting from these and other studies led to a landmark monograph on chromosome imbalance.3 Superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) was another gene residing on chromosome 21; Charlie investigated the role of SOD1 and other homologs in free radical metabolism and aging, an extension of his earlier work on Werner's syndrome. He was also one of the first to formulate the conception that birth defects are caused by mutations in genes that act as pathways—inborn errors of development—similar to biochemical pathways.4 These examples—the study of human diseases such as Down syndrome with mouse models and the concept of inborn errors of development—also illustrate the integration of the basic principles of human genetic diseases with clinical genetics that was a hallmark of Charlie's contribution to the field and was a major motivating force in his research. In fact, Charlie was co-editor (with Bob Erickson and A.W.-B.) of a book Inborn Errors of Development: The Molecular Basis of Clinical Disorders of Morphogenesis.5 As Charlie noted in his McKusick Leadership Award address at last year's ASHG meeting2, “The science is finally catching up to the clinic.”

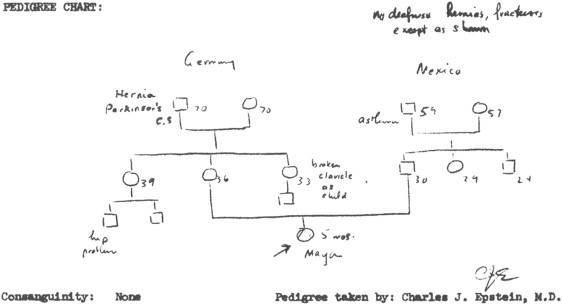

Charlie established training programs for genetics in pediatrics, medicine, and obstetrics and gynecology; these programs ultimately resulted in the establishment of medical genetics and maternal-fetal medicine/medical genetics fellowships at UCSF. He was instrumental in providing the clinical and much of the didactic training for the Genetic Counselor graduate program at University of California, Berkeley between 1974–2004, when the program ceased operation. Of particular historical interest, one individual that welcomed Charlie to the Bay Area and his role at UCSF was Curt Stern (then a genetics professor at University of California, Berkeley and after whom the ASHG Stern Award is named). Curt took advantage of his relationship with Charlie to seek professional advice for his daughter, Holly Stern Ynostroza, who had a concern about a possible genetic condition in her newborn daughter. Of course, Charlie graciously agreed to see Holly and her daughter and was pleased to inform her that her child was normal (see the attached hand-drawn and signed pedigree of the Stern-Ynostroza family, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Stern-Ynostroza Family Pedigree

The pedigree of the Stern-Ynostroza family, prepared and signed by Dr. Charles J. Epstein in 1973. Courtesy of Holly Stern Ynostroza.

Charlie trained more than fifty research fellows in medical genetics and more than one hundred medical genetics resident/fellows and genetic counselors (Figure 3), many of whom now head their own divisions and are leaders in academia and in industry. He taught countless numbers of medical and graduate students over those years. He was a personal friend and mentor to many trainees and faculty not only at UCSF but across the country and internationally. He believed that his role was to produce independent scientists, physicians, genetic counselors, and colleagues. He mentioned several times that his mentors fostered independence in him by allowing him “to decide what needed to be done and how to do it by myself”2. However, he also acknowledged how much he learned from his trainees. In his Leadership Award address,2 Charlie noted, “Although I was officially their mentor, I believe in many ways they were the mentors and I was the student.” This bidirectional mentor-trainee relationship was clearly successful, as demonstrated by the number of successful leaders he has trained in medical genetics research, clinical practice, and genetic counseling.

Figure 3.

Charles Joseph Epstein at Rounds with Fellows and Genetics Counselors

Medical genetics teaching rounds with staff, fellows, and genetic counselors. Photograph courtesy of Vicki Cox.

Charlie was a national and international leader in human and medical genetics, and he influenced all aspects of genetics. He served for seven years as a highly respected editor of AJHG, the premier human genetics journal and the Society's journal. He was elected as President of the three major American human and medical genetics organizations—the scientifically oriented ASHG, the clinically oriented American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG), and the American Board of Medical Genetics (ABMG) that tests the knowledge of medical geneticists. The ABMG was originally created in the early 1980s to certify medical geneticists and genetic counselors and to accredit training programs. However, the ABMG was not recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) and attempts in the 1980s to join the ABMS were unsuccessful. An opportunity presented itself in 1991, and Charlie was one of the driving forces behind medical genetics becoming an accredited medical specialty accepted by the ABMS. The most difficult aspect of this process was that the ABMS refused to include genetic counselors, who did not have MD degrees. As President of the ABMG and editor of the AJHG, Charlie took the lead by writing an editorial in The Journal and holding sessions at the annual ASHG meeting; these actions were decisive in obtaining the two-thirds approval vote of ABMG members needed to join the ABMS. Because 40% of the ABMG consisted of genetic counselors, this was quite a feat and would not have been possible without Charlie's leadership. The independent American Board of Genetic Counseling for genetic counselors and the National Society of Genetic Counselors have both been remarkably successful, a fact that was especially gratifying for Charlie.

Charlie has received all of the major awards of these genetic organizations. He received the William Allen Award from the ASHG in 2001 for his research on mouse models of Down syndrome, and the McKusick Leadership Award, which is awarded to an individual whose achievements have fostered and enriched the development of various human genetics disciplines in 2010, presented to Charlie this past November at the ASHG meeting. Charlie posthumously received the ACMG Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2011 ACMG meeting in Vancouver in March. UCSF and the Buck Institute have established a chair and lectureships. The Charles J. Epstein Professorship in Human Genetics and Pediatrics for the chief of the Division of Medical Genetics was established in honor of his pioneering role in developing the division of medical genetics. One of us was named to that Professorship (A.W.-B.), much to Charlie's delight (and enabling his well-deserved retirement!). To recognize the many contributions made by Charlie and Lois to UCSF, the Charles and Lois Epstein Visiting Professorship was established. Appropriately, the first recipient, in 2010, was Terry Magnuson, a former trainee of Charlie's who is now the Chair of the Department of Genetics at the University of North Carolina. Finally, the Buck Institute established a lectureship in his honor, and the first lecturer this year was Nobel laureate Stanley Prusiner from UCSF. The chair and lectureships will insure that his profound influence on UCSF and Bay Area institutions will be known for generations to come.

Charlie was one of the victims of terror by the Unabomber in 1993, and the attack nearly ended his life. He sustained permanent damage to his hearing, lost the tips of several fingers on his right hand, sustained nerve damage to his right arm that required nerve transplant surgery, and carried shrapnel from the attack with him for the rest of his life. No doubt, he was targeted because of his highly visible public persona in human genetics, and in particular his role at the time as editor of AJHG. In spite of all of these serious injuries, he worked courageously and undauntedly to rehabilitate and continue his research, clinical work, teaching, and service to the community. It was after the attack that Charlie served as president of all of the major genetics organizations listed above. He did not shy away from using his experiences as a strong personal motivation to raise the ethical and social issues derived from the advances in human and medical genetics, as outlined in his ASHG Presidential Address.6 To see Charlie return to research, teaching, clinical work, and especially service to the genetics community was inspirational.

Because of the strong connections he maintained between his research and clinical work and because of his strong ethical convictions, Charlie never lost sight of the goals of his research. His awareness of how genetic conditions are perceived by the public at large was no doubt heightened after the Unabomber attack, but he was always fully engaged in discussions regarding the ethics of human genetics research and practice. He repeatedly emphasized the importance of the individual human being in all these discussions and balanced the hopes and fears of society and the goals and interests of science.1

Charlie has been characterized by many as a “mensch,” someone of strong character, integrity, and honor, and one to be admired and emulated. How apt! Charlie's “menschlich” character was manifest in nearly everything he did, both professional and personal. In addition to his remarkable career as a scientist, clinician, educator, and leader in the human and medical genetics community, Charlie led an incredibly full life. Charlie and Lois shared not only their scientific collaboration but also a large extended family. As known to many, Charlie was devoted to Lois and their four children, David, Paul, Jonathan, and Joanna, and his six grandchildren (Figure 4) and was especially proud of each of their accomplishments. Throughout his life he also remained close to his two brothers Herbert and Edwin and their children, as well as Lois's extended family. Charlie and Lois traveled all over the world, with their children and grandchildren whenever possible, including road trips and festive travel to Hawaii. Together they built magnificent and intricate dollhouses and a lighthouse for their six grandchildren; Charlie was an avid gardener and took great pride in the exquisite garden he created at his home in Tiburon (yet more evidence of Charlie, the architect). Charlie was very happy playing his cello in small and large groups. He was particularly proud to be a member of the Bohemian Club Orchestra, one of the oldest men's clubs in San Francisco. Charlie delighted in participating in the fine music-making of the orchestra (which consisted of both amateur and professional musicians from the San Francisco area). In spite of his injuries from the Unabomber attack, he refused to give up the cello. He worked hard to regain mobility in his fingers, took private lessons, and returned to play with the orchestra for several years. In fact, Charlie had to learn to pluck the cello strings with his fifth finger on his right hand because the other fingers on his right hand were so severely damaged from the attack. It was very satisfying for him to be able to conduct a Mozart bassoon concerto this past December near his home in Marin County while his son Jonathan played the bassoon solo part and his granddaughter Genevieve played the cello in the orchestra.

Figure 4.

Epstein Family Portrait

The Epstein family gathered at the Epstein house in Tiburon for a combined 70th birthday party for Charlie and Lois. Photograph courtesy of Lois Epstein.

Charlie's legacy is enormous. His contributions in any single domain of his remarkable career as a scientist, clinician, educator, and leader in the human and medical genetics community would amount to an extraordinary legacy. That he contributed in all of these areas is a testament to the breadth of his intelligence, encyclopedic knowledge of science, and strong sense of ethics. His parting words at the end of his McKusick Leadership Award speech,2 after acknowledging the support of the Society and his family, were, “I have been truly blessed.” Indeed, it is we, the human genetics community, that has been blessed by the lifelong contributions of this towering figure, a true mensch, talented architect, and courageous leader.

Contributor Information

Anthony Wynshaw-Boris, Email: wynshawborist@peds.ucsf.edu.

Neil Risch, Email: rischn@humgen.ucsf.edu.

Arno Motulsky, Email: agmot@u.washington.edu.

References

- 1.Epstein C.J. 2001 William Allan Award Address. From Down syndrome to the “human” in “human genetics”. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;70:300–313. doi: 10.1086/338915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Motulsky A., Epstein C.J. 2010 Victor A. McKusick Leadership Award introduction and address. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;88:269–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein C.J. University of Cambridge Press; Cambridge, UK: 1986. The Consequences of Chromosome Imbalance. Principles, Mechanisms, and Models. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epstein C.J. The new dysmorphology: application of insights from basic developmental biology to the understanding of human birth defects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:8566–8573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epstein C.J., Erickson R.P., Wynshaw-Boris A.J., editors. Inborn Errors of Development: The Molecular Basis of Clinical Disorders of Morphogenesis. Second Edition. Oxford University Press; New York: 2008. 1617 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epstein C.J. 1996 ASHG Presidential Address. Toward the 21st century. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997;60:1–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]