Abstract

Context:

Two of the important algae from Persian Gulf are Gracilaria salicornia and Hypnea flageliformis (Rhodophyta). Antibacterial, antifungal, and cytotoxic effects of the mentioned algae have been presented in the previous studies.

Aim:

In this study, the isolation and structural elucidation of the sterols from these algae are reported.

Materials and Methods:

The separation and purification of the compounds were carried out with silica gel, sephadex LH20 column chromatography (CC) and HPLC to obtain six pure compounds 1-6. The structural elucidation of the constituents was based on the data obtained from H-NMR,13C-NMR, HMBC, HSQC, DEPT, and EI-MS.

Results:

The isolated compounds from G. salicornia were identified as 22-dehydrocholesterol (1), cholesterol (2), oleic acid (3), and stigmasterol (4), and the isolated constituents from H. flagelliformis were identified as 22-dehydrocholesterol (1), cholesterol (2), oleic acid (3), cholesterol oleate (5), and (22E)-cholesta-5,22-dien-3β-ol-7-one (6) based on the spectral data compared to those reported in the literature.

Conclusion:

Red algae are enriched with cholesterol polysaccharides. We first reported the presence of cholesteryl oleate and (22E)-cholesta-5,22-dien-3β-ol-7-one in H. flagelliformis.

Keywords: Gracilaria salicornia, Hypnea flagelliformis, sterols, (22E)-cholesta-5, 22-dien-3β-ol-7-one

INTRODUCTION

Algae are the large and diverse organisms among the marines, from which many secondary metabolites have been isolated. Some of these compounds possess biological and pharmacological activities.[1–3] Cytotoxic gracilarioside and gracilamides from Gracilaria species, a porcine pancreas elastase (PPE) inhibitor, diketosteroid, from Hypnea musciformis, and a new lectinof H. cervicornis have already been reported.[2,5] Bioactive sterols of Cladophora rivularis, anticoagulant sulfated polysaccharidesof Dictyota menstrualis, and an anti-HSV-1 agent from Cystoseira myrica have been reported.[6,8] Here we report the phytochemical analysis of G. salicornia and H. flagelliformis, which were previously reported for antibacterial and cytotoxic effects, leading to finding their main sterols.[9]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Algae material

Red algae were collected from northern coastal areas of Persian Gulf near to Bandare-Abbas city in July (2007) and identified as Gracilaria salicornia (C. Agardh) E. Y. Dawson and Hypnea flagelliformis Greville ex J. Agardh by Dr. Jelveh Sohrabipour. The voucher specimens (G. salicornia: 53-22R, and H. flagelliformis: 52-21R) are deposited at the Herbarium of Agriculture and Natural Resources Research Center of Hormozgan, Bandar Abbass, Iran.

Experimental

1 H- and 13C-NMR spectra were measured on a Brucker Avance 500 DRX (500 MHz for1 H and 125 MHz for13C) spectrometer (Germany) with tetramethylsilane as an internal standard, and chemical shifts are given in δ (ppm). EI-MS data were recorded on an Agilent Technology (HP) instrument (USA) with the 5973 network mass selective detector (MS model). Silica gel 60F254 precoated plates (Merck, Germany) were used for TLC. The spots were detected by spraying anisaldehyde-H2 SO4 reagent followed by heating. Sephadex LH20 was from Fluka (Switzerland). HPLC was used on a Knauer model with Vertex (Knauer, Germany) column C18 (250 × 20 mm ID). Detector was PDA (UV spectra were collected across the range of 200-900 nm) and injection volume was 2 ml.

Extractions of the marine algae

Marine algae were dried carefully and reduced to small pieces. The dried powder of both algae (1.5 kg) was extracted with chloroform: methanol (3:1) by percolation (72 h) at room temperature. The solvents were then evaporated under reduced pressure to obtain the concentrated extracts, and dried under vacuum in order to give a dried powder of the extracts of H. flagelliformis and G. salicornia (13 g and 15 g, respectively). The dried extract was dissolved in ethyl acetate and decanted three times with distilled water. The ethyl acetate (supernatant) and aqueous parts were dried to gain 3.2- and 9.8-g extracts of H. flagelliformis. The ethyl acetate (supernatant) and aqueous extracts of G. salicornia were found to be 4 and 11 g.

Isolation of the main constituents

G. salicornia

The ethyl acetate extract (4 g) was submitted to the silica gel column chromatography (CC) with hexane, chloroform, CHCl3:AcOEt (1:1), AcOEt, and MeOH consequently, to obtain six fractions (A-F). Fraction E (400 mg) was subjected to silica gel CC, with CHCl3 and CHCl3:AcOEt (5:5) to give five fractions (E1 -E5 ). Fractions E2 and E3 were pure compounds 1 (12 mg) and 2 (19 mg). Fraction E5 (150 mg) was purified on sephadex LH20 with MeOH as an eluent to obtain four fractions (E51 -E54 ). Fraction E53 was the pure compound 3 (7 mg). Compound 4 (12 mg) was obtained from silica gel CC, with CHCl3:AcOEt (8:2), from fraction E54 (66 mg).

H. flagelliformis

The ethyl acetate extract (3.2 g) was submitted to the silica gel CC with hexane, chloroform, CHCl3:AcOEt (1:1), AcOEt, and MeOH consequently, to obtain 10 fractions (A-J). The fraction E (368 mg) was subjected to silica gel CC, with CHCl3 and CHCl3:AcOEt (5:5) to give eight fractions (E1 -E8 ). Fractions E6 and E7 were pure compounds 1 (20 mg) and 2 (13 mg). Fraction E8 was purified on ephadex LH20 with MeOH as an eluent to obtain four fractions (E81 -E84 ). Fraction E83 was submitted to HPLC. Gradient elution (flow rate, 4 ml/min) is followed: Solvent system A was from 25% MeOH (initial state) to 10% MeOH (final state) during 40 min and solvent system B was from 10% MeOH to 100% H2 O during 20 min. Nine fractions were obtained using HPLC (E831 -E839 ). Fractions E834 and E835 were the pure compounds 3 (3 mg) and 5 (15 mg), respectively. Fraction H (208 mg) was subjected to sephadex LH20 with MeOH as an eluent to obtain five fractions (H1 -H5 ). Fraction H3 (83 mg) was submitted to HPLC. Gradient elution (flow rate, 4 ml/min) is followed: Solvent system A was from 75% MeOH to 90% MeOH during 40 min and solvent system B was from 90% MeOH to 100% MeOH during 20 min. Five fractions were obtained using HPLC (H31 -H35 ). Fraction H33 was the pure compound 6 (8 mg).

RESULTS

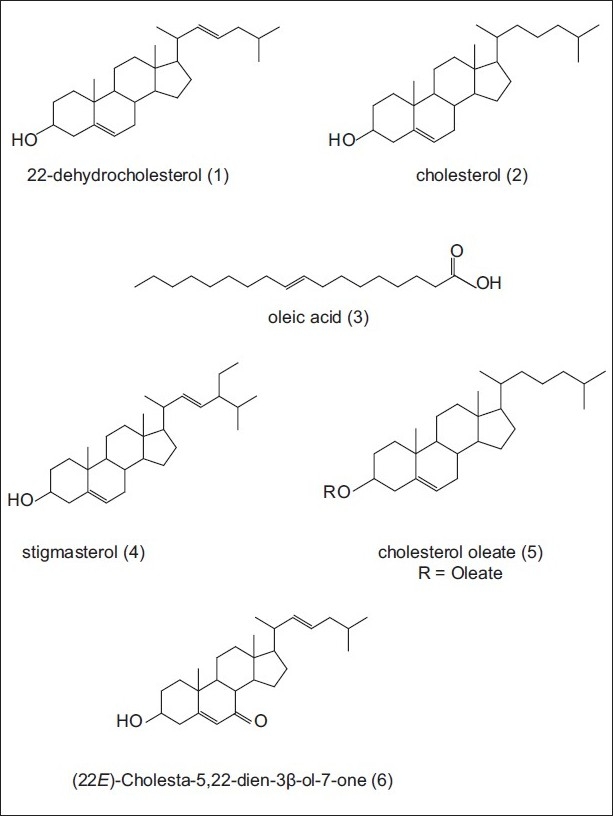

Ethyl acetate extracts of two marine algae (Rhodophyta), G. salicornia and H. flagelliformis, were analyzed in order to isolate the sterol components. The separation and purification of the compounds were carried with silica gel CC and HPLC to obtain six pure compounds 1-6. The structural elucidation of the constituents was based on the data obtained from H-NMR,13C-NMR, HMBC, HSQC, DEPT, and EI-MS. The separated compounds from G. salicornia were identified as 22-dehydrocholesterol (1), cholesterol (2), oleic acid (3), and stigmasterol (4) based on the spectral data compared to those reported in the literature. The structures of isolated constituents from H. flagelliformis were elucidated as 22-dehydrocholesterol (1), cholesterol (2), oleic acid (3) cholesterol oleate (5), and (22E)-cholesta-5,22-dien-3β-ol-7-one (6) [Figure 1].[10–13]13C-NMR data of the sterols are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Structures of the isolated sterols from Gracilaria salicornia and Hypnea flagelliformis

Table 1.

13C -NMR data (δ ppm) of the sterols 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6, isolated from Gracilaria salicornia and Hypnea flagelliformis

| No. | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 37.2 | 37.2 | 37.3 | 37.2 | 36.3 |

| 2 | 31.6 | 31.6 | 31.7 | 31.6 | 31.2 |

| 3 | 71.8 | 71.8 | 71.8 | 71.8 | 70.5 |

| 4 | 42.2 | 42.2 | 42.2 | 42.2 | 41.8 |

| 5 | 140.7 | 140.7 | 140.8 | 140.7 | 165 |

| 6 | 121.7 | 121.7 | 121.7 | 121.7 | 126.1 |

| 7 | 31.9 | 31.9 | 31.9 | 31.9 | 202.2 |

| 8 | 31.9 | 31.9 | 31.9 | 31.9 | 45.4 |

| 9 | 50.2 | 50.2 | 50.2 | 50.2 | 50 |

| 10 | 36.4 | 36.4 | 36.4 | 36.4 | 38.3 |

| 11 | 21.1 | 21.1 | 21.1 | 21.1 | 21.2 |

| 12 | 39.7 | 39.8 | 39.7 | 39.7 | 38.6 |

| 13 | 42.2 | 42.3 | 42.2 | 42.2 | 43 |

| 14 | 56.8 | 56.8 | 56.9 | 56.8 | 51.2 |

| 15 | 24.2 | 24.2 | 24.4 | 24.2 | 26.3 |

| 16 | 28.2 | 28.2 | 28.9 | 28.2 | 28.8 |

| 17 | 55.9 | 56.1 | 56 | 56.1 | 54.6 |

| 18 | 11.8 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12.2 |

| 19 | 19.3 | 19.3 | 19.4 | 19.3 | 17.3 |

| 20 | 40.1 | 35.8 | 40.5 | 35.8 | 39.9 |

| 21 | 20.8 | 18.7 | 21.2 | 18.7 | 21 |

| 22 | 128.1 | 36.2 | 138.3 | 36.2 | 137.9 |

| 23 | 126.2 | 23.8 | 129.3 | 23.8 | 126.4 |

| 24 | 41.9 | 39.5 | 51.6 | 39.5 | 41.9 |

| 25 | 28.6 | 28 | 31.9 | 28 | 28.5 |

| 26 | 22.3 | 22.7 | 19 | 22.7 | 22.3 |

| 27 | 22.2 | 22.6 | 21.1 | 22.6 | 22.3 |

| 28 | - | - | 25.4 | - | - |

| 29 | - | - | 12.2 | - | - |

DISCUSSION

Cholesterol and 22-dehydrocholesterol are found in these algae as two of the main sterols. This is in agreement with the literature which stated that most of the red algae (Rhodophyta) contain primarily cholesterol, although several species contain large amounts of desmosterol, and one species contains primarily 22-dehydrocholesterol. Only a few Rhodophyta contain traces of C-28 and C-29 sterols.[12]

Among the isolated compounds, oleic acid is a monounsaturated fatty acid (C-18) found naturally in many plant sources, well known as the omega-9 fatty acid, and considered one of the healthiest sources of fat in the diet (lower risk of coronary heart disease). There are many known plant sources of high-oleic acid oils such as olive, canola, sunflower, safflower, and Moringa oleifera.[14] Oleic acid may have protective effects against cardiovascular complications of diabetes since glutathione (GSH), total lipid, and triacylglycerol (TAG) levels are beneficially affected. The decreased tissue factor (TF) activity in diabetic-hyperlipidemic persons may protect these tissues from the risk of thrombosis.[15]

This is the first time that we report the presence of cholesteryl oleate in H. flagelliformis. As already reported in the literature, intravenously administered cholesterol oleate emulsion is known to be localized mainly in the Kupffer cells and in the splenic red pulp macrophages. Cultured macrophages treated with this lipid show inhibition of antigen-binding and depressed phagocytosis of heterologous erythrocytes. The lipid does not affect lymphocytes.[16] Among the isolated sterols, (22E)-cholesta-5,22-dien-3β-ol-7-one is separated from H. flagelliformis for the first time. The effects of dietary algae and cholesterol supplementation on postprandial lipemia and lipoproteinaemia and arylesterase (AE) activity in growing male Wistar rats were also reported.[17]

In conclusion, most of the red algae (and other seaweed) are edible, for example, Hypnea used as a salad or in soups. Also, red algae are enriched with cholesterol polysaccharides. Since, high postprandial lipemia increases cardiovascular risk, alga consumption may affect postprandial lipoproteinemia due to its high cholesterol contents.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cannell RJ. Algae as a source of biologically active products. Pest Sci. 2006;39:147–53. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernandez LE, Valiente OG, Mainardi V, Bello JL, Velez H, Rosado A. Isolation and characterization of an antitumor active agar-type polysaccharide of Gracilaria dominguensis. Carbohydr Res. 1989;190:77–83. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(89)84148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prashantkumar P, Angadi SB, Vidyasagar GM. Antimicrobial activity of blue-green and green algae. Indian J Pharma Res. 2006;68:647–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bultel-Ponce V, Etahiri S, Guyot M. New ketosteroids from the red alga Hypnea musciformis. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2002;l2:1715–8. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00295-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bitencourt FS, Figueiredo JG, Mota MR, Bezerra CC, Silvestre PP, Vale MR, et al. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of a mucin-binding agglutinin isolated from the red marine alga Hypnea cervicornis. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 2009;377:1432–912. doi: 10.1007/s00210-008-0262-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamenarska Z, Stefanov K, Dimitrova-Konaklieva S, Najdenski H, Tsvetkova I, Popov S. Chemical composition and biological activity of the brackish-water green alga Cladophora rivularis (L.) Hoek. Bot Marina. 2004;47:215–21. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albuquerque IR, Queiroz KC, Alves LG, Santos EA, Leite EL, Rocha HAO. Heterofucans from Dictyota menstrualis have anticoagulant activity. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2004;37:167–71. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2004000200002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zandi K, Fouladvand M, Pakdel P, Sartavi K. Evaluation of in vitro antiviral activity of a brown agae (Cystoseira myrica) from the Persian Gulf against the Herpes simplex virus type 1. Afr J Biotech. 2007;6:2511–4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saeidnia S, Gohari AR, Shahverdi AR, Permeh P, Nasiri M, Mollazadeh K, et al. Biological activity of two red algae, Gracilaria salicornia and Hypnea flagelliformis from Persian Gulf. Phcog Res. 2009;1:428–30. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goad LJ, Akihisa T. London: Blackie Academic and Professional; 1997. Analysis of sterols; pp. 375–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gohari AR, Saeidnia S, Hadjiakhoondi A, Honda G. Isolation and identification of four sterols from Oud. J Med Plants. 2008;7:47–55. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganchevakamenarska Z, Dimitrovadimitrova-konaklieva S, Stefanov KL, Popov SS. A comparative study on the sterol composition of some brown algae from the Black Sea. Serb Chem Soc. 2003;68:269–75. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riccardis FD, Minale L, Iorizzi M, Debitus C, Levi C. Marine sterols.Side-chain-oxygenated sterols, possibly of abiotic origin, from the new Caledonian sponge. J Nat Prod. 1993;56:282–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohammed AS, Lai OM, Muhammad SKS, Long K, Ghazali HM. Moringa oleifera, Potentially a new source of oleic acid-type oil for Malaysia. In: Hassan MA, editor. Investing in innovation: Bioscience and Biotechnology. Selangor: Universiti Putra Malaysia Press, Serdang Press; 2003. pp. 137–40. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emekli-Alturfan E, Kasikci E, Yarat A. Effects of oleic acid on the tissue factor activity, blood lipids, antioxidant and oxidant parameters of streptozotocin induced diabetic rats fed a highcholesterol diet. Med Chem Res. 2010;19:1011–24. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith II, Dewar AE, Ramage EF, Stuart AE, Adams W. The effect of cholesterol oleate treatment of mice on the rosette forming cell response against sheep erythrocytes. Exp Physiol. 1976;61:45–55. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1976.sp002333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bocanegra A, Bastida S, Benedi J, Nus M, Sanchez-Montero JM, Sanchez-Muniz FJ. Effect of seaweed and cholesterol-enriched diets on postprandial lipoproteinaemia in rats. Br J Nutr. 2009;4:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S000711450999105X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]