Abstract

Heavy metals are natural constituents of the earth's crust, but indiscriminate human activities have drastically altered their geochemical cycles and biochemical balance. This results in accumulation of metals in plant parts having secondary metabolites, which is responsible for a particular pharmacological activity. Prolonged exposure to heavy metals such as cadmium, copper, lead, nickel, and zinc can cause deleterious health effects in humans. Molecular understanding of plant metal accumulation has numerous biotechnological implications also, the long term effects of which might not be yet known.

Keywords: Ayurveda, herbal preparation, hyper accumulation, phytoremediation

Introduction

Any toxic metal may be called heavy metal, irrespective of their atomic mass or density.[1] Heavy metals are a member of an ill-defined subset of elements that exhibit metallic properties. These include the transition metals, some metalloids, lanthanides, and actinides. One source defines heavy metal as one of the common transition metals, such as copper, lead, and zinc. These metals are a cause of environmental pollution from sources such as leaded petrol, industrial effluents, and leaching of metal ions from the soil into lakes and rivers by acid rain.[2] Three principal systems of medicine are practiced in India: Ayurveda, Siddha and Unani-Tibb. These systems utilize drugs of natural origin constituting plants, animals, and mineral preparations.

Heavy Metals/Metalloids

Any metal (or metalloid) species may be considered a “contaminant” if it occurs where it is unwanted, or in a form or concentration that causes a detrimental human or environmental effect. Metals/metalloids include lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), mercury (Hg), arsenic (As), chromium (Cr), copper (Cu), selenium (Se), nickel (Ni), silver (Ag), and zinc (Zn). Other less common metallic contaminants include aluminium (Al), cesium (Cs), cobalt (Co), manganese (Mn), molybdenum (Mo), strontium (Sr), and uranium (U).[3]

History

Ayurvedic medicines originated in India more than 2000 years ago and rely heavily on herbal medicinal products (HMPs).[4] Approximately 80% of India's population use ayurveda through more than one-half million ayurvedic practitioners working in 860 ayurvedic hospitals and 22100 clinics.[5] As early as the 19th century, there were plants identified, which were capable of accumulating uncommonly high Zn levels and hyper accumulating up to 1% Ni in shoots. Following the identification of these and other hyper accumulating species, a great deal of research has been conducted to elucidate the physiology and biochemistry of metal hyper accumulation in plants.[6] In the United States, ayurvedic remedies are now available from South Asian markets, ayurvedic practitioners, health food stores, and the Internet. Because ayurvedic HMPs are marketed as dietary supplements, they are regulated under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA), which does not require proof of safety or efficacy.[7] Since 1978 more than 80 cases of lead poisoning associated with ayurvedic medicine use have been reported worldwide.[8] Metal contamination of garden soils may be widespread in urban areas due to past industrial activity and the use of fossil fuels.[9]

Heavy Metals and Living Organism

Living organisms require varying amounts of heavy metals. Iron, cobalt, copper, manganese, molybdenum, and zinc are required by humans.[10] All metals are toxic at higher concentrations.[9] Excessive levels can be damaging to the organism. Other heavy metals such as mercury, plutonium, and lead are toxic metals that have no known vital or beneficial effect on organisms, and their accumulation over time in the bodies of animals can cause serious illness. Certain elements that are normally toxic are for certain organisms or under certain conditions, beneficial. Examples include vanadium, tungsten, and even cadmium.[1–11] The Types of heavy metals and their effect on human health with their permissible limits are enumerated in Table 1.

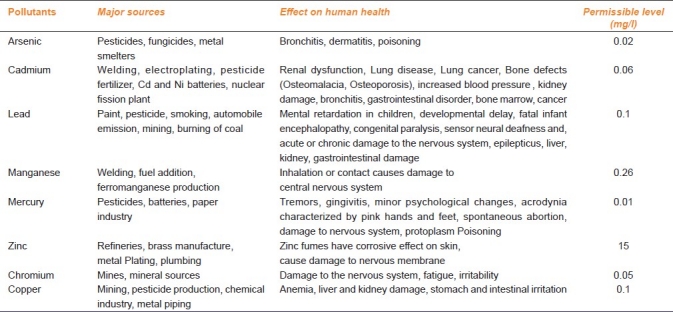

Table 1.

Types of heavy metals and their effect on human health with their permissible limits

Heavy metals disrupt metabolic functions in two ways:

They accumulate and thereby disrupt function in vital organs and glands such as the heart, brain, kidneys, bone, liver, etc.

They displace the vital nutritional minerals from their original place, thereb, hindering their biological function. It is, however, impossible to live in an environment free of heavy metals. There are many ways by which these toxins can be introduced into the body such as consumption of foods, beverages, skin exposure, and the inhaled air.[1]

Plants experience oxidative stress upon exposure to heavy metals that leads to cellular damage and disturbance of cellular ionic homeostasis. To minimize the detrimental effects of heavy metal exposure and their accumulation, plants have evolved detoxification mechanisms mainly based on chelation and subcellular compartmentalization. A principal class of heavy metal chelator known in plants is phytochelatins (PCs), are synthesized no--translationally from reduced glutathione (GSH) in a transpeptidation reaction catalyzed by the enzyme phytochelatin synthase (PCS). Therefore, availability of glutathione is very essential for PCs synthesis in plants at least during their exposure to heavy metals.[12]

On investigating the heavy metal and soil solution chemical changes at field moisture, after growth of either Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) or sunflower (Helianthus annus L.), in lon--term contaminated soils and the subsequent metal uptake by the selected plants, it was reported that soluble Cd and Zn decreased after Indian mustard growth in all soils, and this was attributed to increases in soil solution pH (by 0.9 units) after plant growth. Concentrations of soluble Cu and Pb decreased in acidic soils but increased in alkaline soils, hyper accumulator plants have been shown to either acidify rhizosphere soils and subsequently increase the dissolved concentrations of heavy metals or increase soil pH after plant growth. Increased pH and dissolved organic carbon (DOC) interacted antagonistically with regard to increased metal concentrations in solution. In the acidic soils (pH 6.5), the effect of pH increases was stronger than that of DOC increases, resulting in an overall decrease in dissolved metal concentrations in these soils. In contrast, the increased DOC after plant growth increased dissolved metal concentrations in the alkaline soils. Chemical changes in the rhizosphere also played an important role in controlling the speciation of metals in soil solution. Changes in dissolved metal concentrations and species greatly influenced metal uptake by plants. Plant uptake was primarily related to the concentrations of metals in the soil solution rather than total metal concentrations of the soil.[13]

Heavy Metals and Environmental Pollution

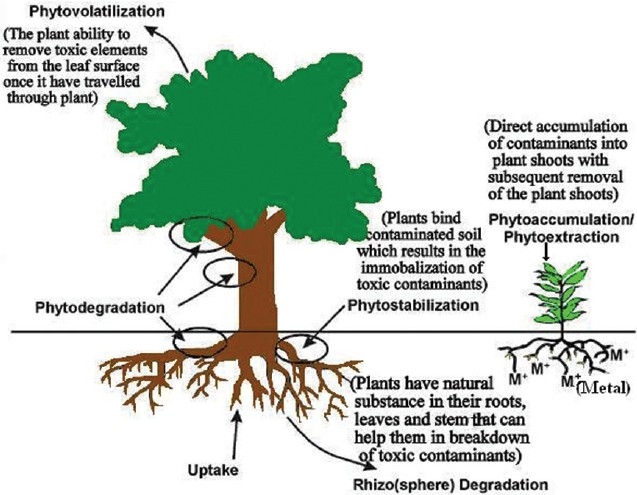

Metal concentration in soil typically ranges from less than one to as high as 100,000 mg/kg.[7] Heavy metals are the main group of inorganic contaminants and a considerable large area o land i contaminated with them due to use of sludge or municipal compost, pesticides, fertilizers, and emissions from municipal wastes incinerates, exudates, residues from metalliferous mines and smelting industries.[14] Irrespective of the origin of the metals in the soil, excessive levels of many metals can result in soil quality degradation, crop yield reduction, and poor quality of agricultural products, posing significant hazards to human, animal, and ecosystem health.[7] Therefore, it becomes essential to remove the accumulated metals. Various processes for removal of heavy metals are shown in Table 2. The removal of single heavy metals like Co and Zn from aqueous solutions using various lo-cost adsorbents (Fe2O3, Fe3O4, FeS, steel wool, Mg pellets, Cu pellets, Zn pellets, Al pellets, Fe pellets, and coal) was investigated. Th solution pH on metal adsorption using Fe2O3 and Fe3O4 was significantly effective, and the removal was p-independent over the entire pH range studied (1.5–9.0).[15] Mechanisms proposed to be involved in transition metal accumulation by plants are phytoaccumulation, phytoextraction, phytovolatilization, phytodegradation, and phytostabilization [Figure 1].[6]

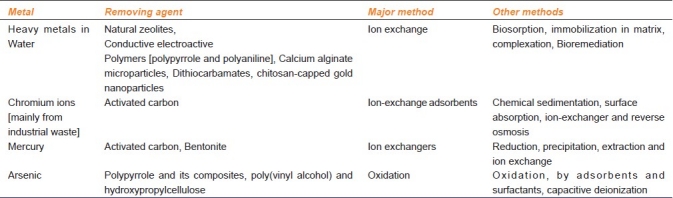

Table 2.

Various processes for removal of heavy metals

Figure 1.

Transition mechanism in plants for metal accumulation

The permissible limits for heavy metals in plant species as per Indian Pharmacopoeia 2007 guidelines are given in Table 3.[1] Research indicates that Nitric Oxide (NO) is involved in the regulation of multiple plant responses to a variety of abiotic and biotic stresses. NO helps plants resist heavy metal stress, first, by indirectly scavenging heavy meta--induced Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), It might be involved in increasing the antioxidant content and antioxidative enzyme activity in plants. Second, by affecting root cell wall components it might increase heavy metal accumulation in root cell walls and decrease heavy metal accumulation in the soluble fraction of leaves in plants. Finally, it could function as a signaling molecule in the cascade of events leading to changes in gene expression under heavy metal stresses.[16]

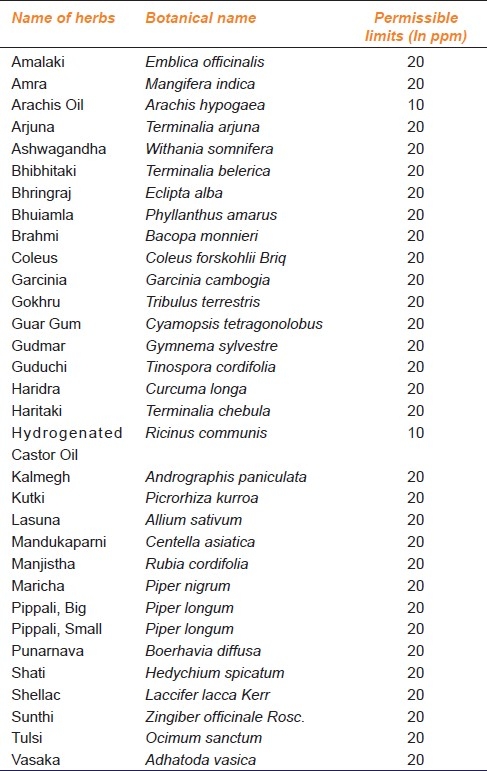

Table 3.

Permissible limits for plant species adopted from Singh MR. Impurities-heavy metals: IR Prespective, 2007[1]

Heavy Metals Contamination of Vegetables

Heavy metal contamination of vegetables cannot be underestimated as these foodstufs are important components of human diet. Vegetables are rich sources of vitamins, minerals, and fibers, and also have beneficial antioxidative effects. However, intake of heavy meta-contaminated vegetables may pose a risk to the human health. Heavy metal contamination of food is one of the most important aspects of food quality assurance. Heavy metals are no-biodegradable and persistent environmental contaminants, which may be deposited on the surfaces and then absorbed into the tissues of vegetables. Monitoring and assessment of heavy metals concentrations in the vegetables from the market sites have been carried out in some developed and developing countries.[17]

Heavy Metals and Polymers

Metal ions are not only valuable intermediates in metal extraction, but also important raw materials for technical applications. Complexation, separation, and removal of metal ions have become increasingly attractive areas of research and have led to new technological developments. Meta--chelating and ion exchange polymers were used in hydrometallurgical applications such as recovery of rare metal ions from seawater and removal of traces of radioactive metal ions from wastes. A polymeric ligand is used to selectively bind a specific metal ion in a mixture to isolate important metal ions from wastewater and aqueous media.dIt is usually used in an insoluble resin form to separate a specific metal ion from a liquid containing a mixture of metal ions. For example, uranium is a potential environmental pollutant, especially in mining industry wastewater, and the migration of uranium in nature is important in this context. Many types of adsorbents were developed and studied for the recovery of uranium from seawater and aqueous media. Among them, amidoxime group containing adsorbents were shown to be the most effective for the recovery of uranium from seawater and aqueous media. The unique advantage of these polymers is that due to its unique chemical structure, it recovers uranium and other transition metal ions from seawater, and aqueous media at very low concentration levels more efficiently.[18] Aspergillus niger immobilized by inclusion in two different polymers: polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel (PVA) and Ca alginate. A. niger biomass absorbed Fe3+, Pb2+, and Cd2+ ions from industrial wastewater more rapidly than other ions within 15 to 20 min. The removal percentages order at equilibrium reported was: Cd2+ (95%) > Pb2+ (88%) > Fe3+ (70%) > Cu2+ (60%) > Ni2+ (48.9%) > Mn2+ (37.7%) > Zn2+ (15.4%). The results showed that immobilized biomass of A. niger, appears as a possible biosorbent to be used for treatment of meta-polluted industrial wastewaters.[19] Efficiency of metal removal depended on the concentration of the metal as well as that of the biosurfactant. In evaluation of a microbial surfactant of marine origin for the remediation of heavy metals, the test anionic surfactant was capable of binding to metal ions even at concentrations lower than its carboxy methyl cellulose (CMC). At five times multiple of its CMC, it was capable of removing nearly the whole metal content. The property of this microbial product to chelate toxic heavy metals and form an insoluble precipitate, may find tremendous application in treatment of heavy metal containing wastewater.[20]

Heavy Metals and Ecosystem

Heavy metal contaminations of land resources continue to be the focus of numerous environmental studies and attract a great deal of attention worldwide. This is attributed to no--biodegradability and persistence of heavy metals in soils. In order to identify spatial relationship of heavy metals in soil-rice system at a regional scale, 96 pairs of rice and soil samples were collected from Wenling in Zhejiang province, China, which is one of the wel--known electronic and electric waste recycling centers. The results indicated some studied areas had potential contaminations by heavy metals, especially by Cd. The spatial distribution of Cd, Cu, Pb, and Zn illustrated that the highest concentrations were located in the northwest areas and the accumulation of these metals may be due to the industrialization, agricultural chemicals and other human activities.[21] Municipal solid waste (MSW) fly ash is classified as a hazardous material because it contains high amounts of heavy metals. For decontamination, MSW fly ash is first mixed with alkali or alkaline earth metal chlorides (e.g., calcium chloride) and water, and then the mixture is pelletized and treated in a rotary reactor at about 1000°C. More than 90% of Cd and Pb and about 60% of Cu and 80% of Zn could be removed in the experiments.[22] Among various water purification and recycling technologies, adsorption is a simple, inexpensive, and universal method. Spent grain is an abundantly available brewing industrial waste generated in the mashing process. Spent grain is a lignocellulosic biomass, which mainly consists of hemicellulose (30–35%), cellulose (23–25%), and lignin (7–8%). In principle, citric acid can directly interact with the hydroxyl groups of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin in spent grain by esterification, which produced an effective adsorbent (ESG), suitable for adsorption of heavy metal ions which can be utilized as a new lo--cost adsorbent for heavy metal ions removal.[23] Phytoremediation crop disposal is a problem inhibiting the widespread use of the remediation technique. Flash pyrolysis as processing method for metal contaminated biomass, low pyrolysis temperature prevents metal compounds from volatilisation while valuable pyrolysis oil is produced. Biomass and pyrolysis products are analysed with the focus on the metal distribution; target elements include Zn, Cd, Pb and Cu. IC--AES measurements confirm very low levels of metals in pyrolysis oil produced at 623 K (Cu and Zn <5 ppm; Cd and Pb <1 ppm) with almost all of the metals accumulated in the char/ash residue. Pyrolysis mass and energy balances are determined providing information in view of future valorisation purposes Flash pyrolysis ca offer a valuable processing method for heavy metal contaminated biomass, thus limiting the waste disposal problem associated with phytoremediation.[24] Lead and Zn uptake and chemical changes in rhizosphere soils of four emergen--rooted wetland plants; Aneilema bracteatum, Cyperus alternifolius, Ludwigia hyssopifolia and Veronica serpyllifolia were investigated. The results showed that the wetland plants with different Radial Oxygen Loss (ROL) rates had significant effects on the mobility and chemical forms of Pb and Zn in rhizosphere under flooded conditions. For Pb, as a no--essential element, the wetland plants are able to decrease its mobility in both “clean” soil (with lower Pb) and polluted soil (and higher Pb); while for Zn, as an essential element, the plants are able to increase its mobility in “clean” soil (with lower Zn), but decrease its mobility in polluted soil (with higher Zn). Among the four plants, V. serpyllifolia, with the highest ROL, formed the highest degree of Fe plaque on the root surface, immobilized more Zn in Fe plaque, and has the highest effects on the changes of Zn form in rhizosphere under both “clean” and contaminated soil conditions. These results suggested that ROL of wetland plants could play an important role in Fe plaque formation and mobility and chemical changes of metals in rhizosphere soil under flood conditions.[25]

The sewage sludge used in a study which had high content of organic C, available nutrients and heavy metals, its amendment led to higher concentrations of organic carbon, total N, available P and exchangeable Na+, K+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ in plants. This increases the beneficial utilization of sewage sludge for agriculture.[26] High contents of organic matter and nutrients make sewage sludge a perfect material for fertilization and recultivation of degraded soils. In the case of all sludges (in the proportion of 6%), a stimulating influence on seed germination was observed and inhibiting influence of sludges on germination and root growth observed in the case of cress (L. sativum) and barley (Hordeum vulgare). Toxic levels of heavy metals in the soil are responsible for the reduced chlorophyll content of the plants growing in polluted areas. After composting of sewage sludges, positively influences on the growth and development of L. sativum were noted.[27] The alternative aaerobic and aerobic composting of sewage sludge with organic garbage is a good way for improving the characteristics of sludge for the reuse and application in comparison with sewage sludge, the concentrations of heavy metals in the compost, such as Cu, Ni, Cd, Cr, Pb, and Zn, would decrease because of the dilution and fermentation. The results of the uptake of heavy metals by watercress show that the accumulation of Cu, Ni, Cd, Cr, Pb, and Zn in the crop is much lower than that required by the limited levels of Chinese criteria for vegetables. Watercress is a proper plant to be used in amended kailyard (KY) soil with compost of sewage sludge without any threat of bi--magnification of heavy metals.[28] Mangrove wetlands are important in the removal of nutrients, heavy metals, and organic pollutants from wastewater within estuarine systems due to the presence of oxidized and reduced conditions, periodic flooding by incoming and outgoing tides, and high clay and organic matter content. Study suggested that mangrove wetlands with Sonneratia apetala Buc--Ham species had great potential for the removal of nutrients and heavy metals in coastal areas. Wetland plants not only take up nutrients (e.g., N and P) and heavy metals, but also control the ventilation and microbial conditions in the wetland bed. The amount of total biomass for Sonneratia apetala Buc--Ham increased with wastewater nutrient concentrations, while the magnitude of heavy metal contents in the biomass was in the following order: Cu > Pb > Cd > Zn. Very good linear correlations existed between the biomass and the nutrients or heavy metals. In general, more than 98% of the heavy metals in the wastewater were removed by the soil and the rest of about 2% heavy metals were removed by the plant. This concluded that the Sonneratia apetala Buc--Ham species was more effective in the removal of nutrients than heavy metals.[29]

Evidence in Support of Heavy Metals

Heavy metals are toxic, but their oxides are usually not. Food and Drug Administration has approved arsenic trioxide to be used in Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL).[30] There are some reports published on the harmful effects of ayurvedic Bhasmas of Indian system of medicine. Actually the Bhasmas can be toxic or harmful to humans only if they are not prepared in the correct manner.[31] The preparations are then prescribed with certain Anupanas (accompaniments), e.g., ginger or cumin water, tulsi extract, etc. that have been shown to protect against unwanted toxicity due to varied reasons,[32,33] including high proportions of trace elements and synergistic or protective effects due to buffering between various constituents. As per Ayurveda, the bioavailability and toxicity of the metals depend on their chemical forms, especially of mercury, although some authors could not ascertain it experimentally.[34,35] An example of non-toxicity of ayurvedically processed (as suggested in Shastras) so-called toxic herbs are given as: crude aconite at 2.5 mg/mouse produces 100% mortality. ayurvedically processed aconite (compound A) the root of the plant was boiled with two parts of cow's urine for 7 hours per day for two consecutive days. The root was then thoroughly washed with water and boiled with two parts of cow's milk for the same duration. Processed aconite (compound B) processed only in cow's urine for 7 hr per day for 2 consecutive days. Aconite processed only in cow's milk for the same duration (compound C) was also considered safe at 20 mgs. The study exhibited that compound A was totally non toxic followed by compound B and C, respectively, which were also reported to be safer than crude aconite.[31]

Mercurous mercury, also called calomel, was used as diuretic, antiseptic, skin ointment, vitiligo, and laxative for centuries. Calomel was also used in traditional medicines, but now these uses have largely been replaced by safer therapies. Other preparations containing mercury are still used as antibacterials.[36] Rasa shastra experts claim that these medicines, if properly prepared and administered, are safe and therapeutic. Navbal Rasayan (NR) a metal based ayurvedic formulation is used for the treatment of multiple sclerosis; study with NR in animals does not show any toxic effect. However, decrease or attenuation of agonistic activities of histamine, acetylcholine and serotonin needs further exploration.[37] Two gold preparations, ayurvedic Swarna Bhasma and unani Kushta Tila Kalan are claimed to possess general tonic, hepatotonic, nervine tonic, cardiostimulant, aphrodisiac, detoxicant, antiinfective and antiaging properties.[38,39] In modern medicine, gold compounds (e.g., gold disodium thiomalate and auranofin) have been used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis for more than sixty years with well documented effects on immune function.[40] Marked analgesic (elicited through opioidergic mechanisms) and immunostimulant effects of these preparations with a wide margin of safety have been reported.[41] Anticataleptic, antianxiety, and antidepressant properties are also observed.[42]

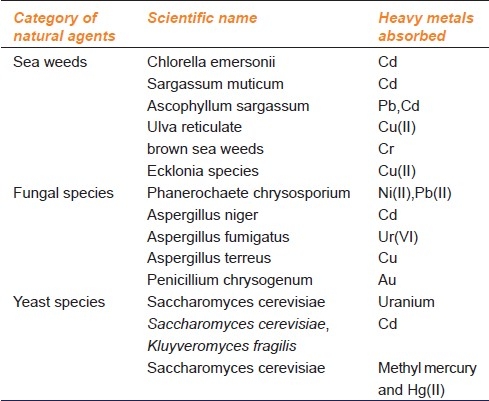

Tamra Bhasma, a metallic ayurvedic preparation, is a time-tested medicine in ayurveda and is in clinical use for various ailments specifically the free radical mediated diseases. Studies show that Tamra Bhasma inhibits lipid peroxidation (LPO), prevents the rate of aerial oxidation of reduced glutathione (GSH) content and induces the activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) in rat liver homogenate in the biphasic manner.[43] Tamra Bhasma is recommended in the dose of 10 mg to 30 mg for an adult (70 kg body weight; 0.2 mg/kg) to manage liver disorders, gastro-intestinal tract (GIT) disorders, old age diseases, leucoderma, cardiac problems, and various other free radical-mediated disorders, either alone or as herbo-mineral compositions.[44,45] Apart from all these, there are natural agents, which lead to absorption of heavy metals are shown in Table 4.[46]

Table 4.

Heavy metal absorbing capability of various natural agents adopted from Karnika et al Biosorption: An eco-friendly alternative for heavy metal removal, 2007[46]

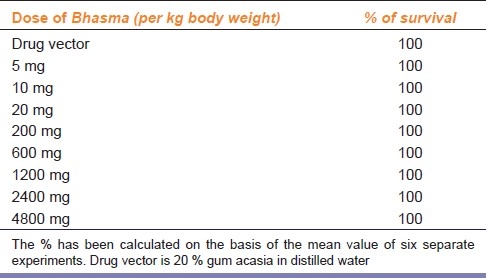

Deficiency of copper in the body causes weight loss, bone disorders, microcytic hypochromic anaemia, hypopigmentation, graying of hair and demyelination of nerves etc.[47] It is reported that Tamra Bhasma potentiates the antioxidant activity of animals, when given orally treated animals showed less degree of lipid peroxidation. Results clearly indicated that Tamra Bhasma does have antioxidant property in low doses, without any side effect, even up to 90 days of treatment in the dose of 5 mg/kg body weight. However in higher doses, when given for a longer period, it induced lipid peroxidation, without any effect on the rate of survival but these tested doses are much higher than the human therapeutic doses.[43,48] Table 5 illustrates the effect of Tamra Bhasma on the survival of albino rats up to 30 days.[43]

Table 5.

Effect of Tamra Bhasma on the survival of albino rats up to 30 days adopted from Pattanaik N. Toxicology and free radicals scavenging property of Tamra Bhasma 2003.[43]

Heavy metals may exert their acute and chronic effects on the human skin through stress signals. Findings suggest that heavy metals reduced the phosphorylation level of small heat shock protein 27(HSP27), and that the ratio of p-HSP27 and HSP27 may be a sensitive marker or additional endpoint for the hazard assessment of potential skin irritation caused by chemicals and their products.[49]

Contradictory Claims about the Effect of Heavy Metals

It is generally believed that herbal and natural products are safer than the synthetic or modern medicines but even some indigenous herbal products contain heavy metals as essential ingredients. Thus the expanded use of herbal medicine has led to concerns relating to its safety, quality, and effectiveness especially for Bhasmas as these are usually made of heavy metals like arsenic, mercury, copper, zinc, gold, and silver. Therefore, contamination of herbal drugs with heavy metals is of prime concern. Prolonged exposure to heavy metals such as cadmium, copper, lead, nickel, and zinc can cause deleterious health effects in humans.[50] Although many of traditional remedies are used safely, there have recently been an increasing number of case reports being published of heavy metal poisoning after the use of traditional remedies, in particular, Indian ayurvedic remedies.[51] These were started extensively after the study showed high levels of lead, mercury and arsenic found in ayurvedic products sold in US,[52] and this lead to a strong evidence for further quality and safety issues. The Indian population who frequent purchase ayurvedic herbal supplements, Bhasmas and Rasa, may not have understood that the traditional formulation contained heavy metals requiring special care and supervision. Inhalation of mercury vapour produces acute corrosive bronchitis and interstitial pneumonitis and, if not fatal, may be associated with central nervous system effects such as tremor or increased excitability.[34,53] Inhalation of large amounts of mercury vapour can be fatal. With chronic exposure to mercury vapour, the major effects are on the central nervous system. The triad of tremors, gingivitis and erethism (memory loss, increased excitability, insomnia, depression, and shyness) has been recognized historically as the major manifestation of mercury poisoning from inhalation of mercury vapor. Sporadic instances of proteinuria and even nephrotic syndrome may occur in persons with exposure to mercury vapour, particularly with chronic occupational exposure.[34,53] Methyl mercury crosses the placenta and reaches the fetus, and is concentrated in the fetal brain at least 5 to 7 times that of maternal blood.[36] The adverse effects of gold salts particularly on prolonged use (nephrotoxic, bone marrow depression, cutaneous reactions, and blood dyscriasis etc.) are well documented.[40] The preparations under study are not gold salts but calcined preparations of gold used in Ayurveda (SB) and Unani-Tibb (KTK) and involve incorporation of herbal juices (Aloe vera, Dolichos uniflorus, Rosa damascena), minerals (mercury, sulfur) and animal origin ingredients (whey, cow's urine) during the ashing process.[38,39] They constitute unidentified complexes of the metal which may not have properties and biological effects akin to gold salts. Kushta Tila Kalan (KTK) and Swarna Bhasma (SB) reported to produce immunostimulant, rather than immunosuppressant actions and analgesic actions, without descernible untoward effects at the doses used.[42]

Conclusion

Worldwide debate is on for the use of ayurvedic metallic preparations. The use of herbal medicine, the dominant form of treatment in developing countries has been increasing in recent years.[50] Some of the herbs selectively absorb and accumulate the heavy metals from the soils, which in turn can be utilized to decontaminate the soils . Several metallic preparations are in clinical use since 12th century. They have specific methods for their detoxification and Bhasma preparation, which becomes suitable for clinical use in therapeutic doses. Since centuries these preparations are sustaining themselves in use, therefore one can not just simply write off its usage just by assuming that heavy metals are toxic. Proper scientific documentation is the demand of time to validate the claims about these metallic preparations and also to ascertain whether the conventional Shodhan (purification) process of ayurveda is being properly followed or not. Post controversy reports, it has now been made mandatory (WHO guidelines) that herbal products should be tested for their heavy metal content prior to export so that heavy metals remain within permissible limits.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Singh MR. Impurities-heavy metals: IR prespective. 2007. [Last cited on 2009 Aug 10]. Available from: http://www.usp.org/pdf/EN/meetings/asMeetingIndia/2008Session4track1.pdf .

- 2.A dictionary of chemistry. Oxford university press. Oxford reference [Online]. Oxford University Press. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mcintyre T. Phytoremediation of heavy metals from soils. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2003;78:97–123. doi: 10.1007/3-540-45991-x_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chopra A, Doiphode W. Ayurvedic medicine: Core concept, therapeutic principles, and current relevance. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86:75–89. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(03)00073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gogtay NJ, Bhatt HA, Dalvi SS, Kshirsagar NA. The use and safety of non-allopathic Indian medicines. Drug Saf. 2002;25:1005–19. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200225140-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang XE, Long XX, Ni WZ, Fu CX, Sedum alfredii H. A new Zn hyperaccumulating plant first found in China. China Sci Bull. 2002;47:1634–7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Long XX, Yang XE, Ni WZ. Current status and prospective on phytoremediation of heavy metal polluted soils. J Appl Ecol. 2002;13:757–62. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ernst E. Heavy metals in traditional Indian remedies. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;57:891–6. doi: 10.1007/s00228-001-0400-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chronopoulos J, Haidouti C, Chronopoulou A, Massas I. Variations in plant and soil lead and cadmium content in urban parks in Athens, Greece. Sci Total Environ. 1997;196:91–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lane TW, Morel FM. A biological function for cadmium in marine diatoms. Proc Natl Acad Sc. . . . 200 ;9) [Last cited on 2009 Aug 13]. pp. 462–31. Available from: http://www.pnas.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=lon&andpmid=10781068 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Lane TW, Saito MA, George GN, Pickering IJ, Prince RC, Morel FM. Biochemistry: A cadmium enzyme from a marine diatom. Nature. 2005;435:42. doi: 10.1038/435042a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yadav SK. Heavy metals toxicity in plants: An overview on the role of glutathione and phytochelatins in heavy metal stress tolerance of plants. S Afr J Bot. 2010;76:16–179. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim KR, Owens G, Naidu R. Effect of roo--induced chemical changes on dynamics and plant uptake of heavy metals in rhizosphere soils. Pedosphere. 2010;20:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halim M, Conte P, Piccolo A. Potential availability of heavy metals to phytoextraction from contaminatrd soils induced by exogenous humic substances. Chemosphere. 2002;52:26–75. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang YH, Lin SH, Juang RS. Removal of heavy metal ions from aqueous solutions using various lo--cost adsorbents. J Hazard Mater. 2003B;102:29–302. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3894(03)00218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiong J, Fu G, Tao L, Zhu C. Roles of nitric oxide in alleviating heavy metal toxicity in plants. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;497:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma RK, Agrawal M, Marshall FM. Heavy metals in vegetables collected from production and market sites of a tropical urban area of Indi. Food Chem Toxicol. 2009;47:58–91. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kavakl PA, Guven O. Removal of concentrated heavy metal ions from aqueous solutions using polymers with enriched amidoxime groups. J Appl Polym Sci. 2004;93:1705–10. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsekova K, Todorova D, Ganeva S. Removal of heavy metals from industrial wastewater by free and immobilized cells of Aspergillus niger. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation. 2010;64:44–51. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Das P, Mukherjee S, Sen R. Biosurfactant of marine origin exhibiting heavy metal remediation properties. Bioresour Technol. 2009;100:488–90. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao K, Liu X, Xu J, Selim HM. Heavy metal contaminations in a soil–rice system: Identification of spatial dependence in relation to soil properties of paddy fields. J Hazard Mater. 2010;181:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.05.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nowak B, Pessl A, Aschenbrenner P, Szentannai P, Mattenberger H, Rechberger HF, et al. Heavy metal removal from municipal solid waste fly ash by chlorination and thermal treatment. J Hazard Mate. 2010;179:32–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Q, Chai L, Wang Q, Yang Z, Yan H, Wang Y. Fast esterification of spent grain for enhanced heavy metal ions adsorption. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101:379–99. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stals M, Thijssen E, Vangronsveld J, Carleer R, Schreurs S, Yperman J. Flash pyrolysis of heavy metal contaminated biomass from phytoremediation: Influence of temperature, entrained flow and wood/leaves blended pyrolysis on the behaviour of heavy metals. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2010;87:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang J, Ma Z, Ye1 Z, Guo X, Qiu R. Heavy metal (Pb, Zn) uptake and chemical changes in rhizosphere soils of four wetland plants with different radial oxygen loss. J Environ Sci. 2010;22:69–702. doi: 10.1016/s1001-0742(09)60165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh RP, Agrawal M. Variations in heavy metal accumulation, growth and yield of rice plants grown at different sewage sludge amendment rates. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2010;73:63–641. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oleszczuk P. Phytotoxicity of municipal sewage sludge composts related to physic--chemical properties, PAHs and heavy metals. Ecotoxicol Environ Say. 2008;69:49–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sha--qia Z, We--donga L, Xiao Z. Effects of heavy metals on planting watercress in kailyard soil amended by adding compost of sewage sludge. Process Saf Environ Prot. 2010;88:26–68. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jia-En Z, Jin-Ling L, Ying O, Bao-Wen L, Ben-Liang Z. Removal of nutrients and heavy metals from wastewater with mangrove Sonneratia apetala Buc-Ham. Ecol Eng. 2010;36:807–12. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Antman KH. Introduction: The history of arsenic trioxide in cancer therapy. Oncologist. 2001;6:1–2. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.6-suppl_2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thorat S, Dahanukar S. Can we dispense with ayurvedic samskaras.? J Postgrad Med. 1991;37:15–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma MK, Kumar M, Kumar A. Ocimum sanctum aqueous leaf extract provides protection against mercury induced toxicity in Swiss albino mice. Indian J Exp Biol. 2002;40:107–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samudralwar DL, Garg AN. Minor and trace elemental determination in the Indian herbal and other medicinal preparations. Biol Trace Elem Res. 199g;54:11–21. doi: 10.1007/BF02786258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klaassen CD. Goodman and Gilman's: The pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 10th ed. New York: McGraw--Hill Professional; 2001. Heavy metals and heavy metal antagonists; pp. 1851–76. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gochfeld M. Cases of mercury exposure, bioavailability, and absorption. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2003;56:17–9. doi: 10.1016/s0147-6513(03)00060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toxicological profile for mercury (update) Vol. 199. Atlanta: Agency for toxic substances and disease registry; Agency for toxic substances and disease registry; p. 485. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chandra D, Mandal AK. Toxicological and pharmacological study of Navbal Rasayan - A metal based formulation. Indian J Pharmacol. 2000;32:36–71. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chopra RN, Chopra IC, Handa KL, Kapur LD. 2nd en. Vol. 198. Calcutta: Academic Publishe; Chopra's indigenious drugs of India; pp. 46–64. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kabeeruddin WA. Vol. 199. New Delhi: Darul Kutub ul Masseh; Kita--u--Taqlees il----Kusht--e Jat (Urdu) pp. 15–58. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bloom JC, Thiem PA, Halper LK, Saunder LZ, Morgan DG. The effect of long term treatment with auranofin and gold sodium thiomalate on immune function of dog. J Rheumatoy. 1988;15:409–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bajaj S, Vohora SB. Analgesic effects of gold preparations used in Ayurveda and Unan--Tibb. Indian J Med Res. 1998;108:10–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bajaj S, Vohora SB. Ant--cataleptic, ant-anxiety and ant--depressant activity of gold preparations used in Indian systems of medicine. Indian J Pharmacol. 2000;32:33–346. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pattanaik N. Toxicology and free radicals scavenging property of Tamra Bhasma. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2003;18:18–89. doi: 10.1007/BF02867385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ciba foundation symposium 79 (New Series) Excerpta Medic. New York: Oxford Publishe; 1980. Biological roles of copper. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Said M. Vol. 196. Karachi: Hamdard Foundatio; Hamdard Pharmacopoeia of Eastern Medicine; pp. 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karnika AH, Reddy RS, Saradhi SV, Singh J. Biosorption: An ec--friendly alternative for heavy metal removal. Afr J Biotechnol. 2007;6:292–31. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pandey BL. A study of the effect of Tamra bhasma on experimental gastric ulcers and secretions. Indian J Exp Biol. 1983;21:25–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tripathi YB, Singh VP. Role of Tamra bhasma and ayurvedic preparation in the management of lipid peroxidation in liver of albino rats. Indian J Exp Biol. 1996;34:6–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Q, Zhang L, Xiao X, Su Z, Zou P, Hu H, et al. Heavy metals chromium and neodymium reduced phosphorylation level of heat shock protein 27 in human keratinocytes. Toxico. In Vitro. 2010;24:1098–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reilly C. 2nd ned. London and New York: Elsevier Science Publishers Lt; 1991. Metal Contamination of Foo. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lynch E, Braithwaite R. A review of the clinical and toxicological aspects of ‘traditional’ (herbal) medicines adulterated with heavy metals. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2005;4:76–8. doi: 10.1517/14740338.4.4.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saper RB, Kales SN. Heavy metal content of ayurvedic herbal medicine products. JAMA. 2004;292:2868–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.23.2868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. [Last cited on 2010 May 20]. Available from: http://www.amazon.com/Casaret--Doull--Toxicolog--Scienc--Poisons/dp/0071347216 .