Abstract

More than 90% of pregnant women take prescription or non-prescription drugs at some time during pregnancy. In general, unless absolutely necessary, drugs should not be used during pregnancy because many of them are harmful to the fetus. Appropriate dispensing is one of the steps for rational drug use; so, it is necessary that drug dispensers should have relevant and updated knowledge and skills regarding drug use in pregnancy. To assess the knowledge of drug dispensers and pregnant women regarding drug use in pregnancy, focusing on four commonly used drugs that are teratogenic or cause unwanted effects to the fetus and babies. The study was conducted in two parts: consumers′ perception and providers′ practice. It was a cross-sectional study involving visits to 200 private retail community pharmacies (as simulated client) within Temeke, Ilala and Kinondoni municipals in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. The second part of the study was conducted at the antenatal clinics of the three municipal hospitals in Dar es Salaam. A semi-structured questionnaire was used to gather information from pregnant women. In total, 200 pregnant women were interviewed. Out of 200 drug dispensers, 86 (43%) were willing to dispense artemether-lumefantrine (regardless of the age of pregnancy), 56 (29%) were willing to dispense sodium valproate, 104 (52%) were willing to dispense captopril and 50 (25%) were willing to dispense tetracycline. One hundred and thirty-three (66.5%) pregnant women reported that they hesitated to take medications without consulting their physicians, 47 (23.5%) indicated that it was safe to take medications during pregnancy, while 123 (61.5%) mentioned that it was best to consult a doctor, while 30 (15%) did not have any preference. Sixty-three (31.5%) women reported that they were aware of certain drugs that are contraindicated during pregnancy. It is evident that most drug dispensers have low knowledge regarding the harmful effects of drugs during pregnancy. Drug dispensing personnel should be considered part of the therapeutic chain and, if appropriately trained, they will play a very important role in promoting rational use of medicines.

Keywords: Drug dispensers, knowledge, pregnancy, pregnant women, teratogenic drugs

Introduction

Drug treatment during pregnancy presents a special concern due to potential teratogenic effects of some drugs and physiologic adjustments in the mother in response to pregnancy.[1,2] The use of drugs during pregnancy therefore calls for special attention because in addition to the mother, the health and life of her unborn child is also at risk.[3] The drug or metabolite concentration may be even higher in the embryonic or fetus compartment than in the mother. As a result, the fetus as an “additional” patient demands strict pharmacotherapeutic approach.

Total avoidance of pharmacological treatment in pregnancy is not possible and may be dangerous because some women become pregnant with medical conditions that require ongoing and episodic treatment.[2] Sometimes drugs are therefore essential for the health of the pregnant woman and the fetus. In such cases, a woman should talk with her physician or other health care providers about the risks and benefits of taking the drugs. For instance, in chronic conditions such as epilepsy, bronchial asthma, diabetes mellitus or infectious diseases, treatment is obligatory regardless of pregnancy.[2] In contrast, inessential products such as cough preparations, pregnancy supporting substances, high doses of vitamins and minerals are contraindicated as their potential risks outweigh their unproven benefits.

Appropriate dispensing is one of the key steps for rational drug use including minimizing the use of teratogenic drugs during pregnancy.[4,5] It is necessary that a drug dispenser should have relevant and updated knowledge and skills regarding dispensing of drugs during pregnancy. A misperception of the risk may lead to inappropriate decisions for pregnancy outcomes. On the other hand, perception of risk may influence a woman's decision to take a needed drug during pregnancy.[6] There is a general perception that drugs are not safe in pregnancy despite the fact that fewer than 30 drugs have been shown to cause major malformations in humans.[7] Avoidance of unnecessary use of drugs during pregnancy as well as knowledge and awareness of care providers and pregnant women concerning the harmful effect of drugs is of great significance.

Community retail pharmacies represent a readily and easily accessible point of contact for the public where they obtain medicines, drug information and medical advice.[8,9] These premises are particularly important in developing countries like Tanzania where many people do not have medical insurance. Drug dispensers have an important role in providing correct information and pharmaceutical services to patients including pregnant women. Since it has been reported that women generally overestimate the risk of teratogenicity of drugs,[10] it is important for health care providers including drug dispensing personnel to use evidence-based information so as to reduce unnecessary anxiety, and to ensure safe and appropriate drug use during pregnancy.[6]

Materials and Methods

Study Area

The study was conducted from December 2009 till May 2010 in Dar es Salaam, the commercial capital city of Tanzania. The city is divided into three municipals: Kinondoni, Ilala and Temeke. Drug dispensers working in the private retail community pharmacies within these municipals were assessed for rational dispensing to pregnant women. Each of the three municipals in Dar es Salaam has a public municipal hospital which provides health care services to the people within and outside the municipal. Therefore, pregnant women were interviewed at Mwanyanamala hospital (Kinondoni municipal), Amana hospital (Ilala municipal) and Temeke hospital (Temeke municipal).

Study Design

This was a cross-sectional descriptive study involving visits to the private retail community pharmacies (as simulated client) and interviewing pregnant women at the antennal clinics in the municipal hospitals in Dar es Salaam.

Sampling, Sample size and Data collection

Community pharmacies

A list of registered pharmacies was obtained from Tanzania Food and Drugs Authority. Using this list, selection of pharmacies was based on random sampling process in which pharmacies available in each municipal were first listed and assigned numbers. Simple random sampling done using balloting method was then used to select community pharmacies from each municipal. Pharmacies for inclusion in the study were selected according to their proportions from each municipal so as to provide a representative sample for each. Therefore 94, 82 and 24 pharmacies were selected from Kinondoni, Ilala and Temeke municipals, respectively. Thus, a total of 200 pharmacies were visited to assess drug dispenser's knowledge about drug use during pregnancy.

A checklist was used to assess the knowledge levels of drug dispensers in the community pharmacies regarding dispensing and use of potential teratogenic drugs during pregnancy. Three potential teratogenic drugs were selected as tracer drugs for the study. These drugs are artemether-lumefantrine,[11] sodium valproate[12] and captopril.[13] In addition, tetracycline, which is known to cause yellow-brown discoloration of the deciduous teeth (a fetal effect),[14,15] was also used in the study. A researcher posing as a surrogate pregnant shopper visited retail community pharmacies requesting for the chosen drugs. Immediately after leaving the pharmacy, the surrogate pregnant shopper filled in the information in the checklist. The information included counseling, willingness to dispense the drugs, questions asked regarding age of pregnancy and other information about use of potential teratogenic drugs during pregnancy.

A knowledge scale was used to assess the drug dispenser's knowledge. One point was awarded for a correct answer and zero point for a wrong answer. The knowledge scale included four items concerning the risk of drugs during pregnancy. These were correct reasons and advice provided by drug dispenser regarding use of the chosen drugs during pregnancy. Drug dispenser's knowledge was then assessed as low (0–1 score), medium (2–3 score) and high (4–6 score).

Pregnant women interviews

Pregnant women were selected using convenient sampling due to their limited availability at antenatal clinics. Each consenting pregnant woman (18 years and above) attending the antenatal clinic on the day of interview was interviewed. A total of 200 pregnant women were interviewed (68 at Mwanyanamala hospital, 80 at Temeke hospital and 52 at Amana hospital). A semi-structured questionnaire designed to assess the awareness and knowledge of pregnant women with regard to drug use during pregnancy was used for interview. The main focus was on the use of potential teratogenic drugs during pregnancy. The instrument was divided into two parts: socio-demographic factors and the knowledge scale regarding the effect of taking drugs during pregnancy. The background factors included age of the pregnant women, duration of pregnancy, parity, level of education and occupation.

Data Analysis

The data collected were analyzed using Epi Info (version 3.4). Summary statistics were employed to describe categorical data. Chi-square and Fisher exact test (t-test) were used to calculate P-value and to compare the knowledge of drug dispensers and pregnant women against study variables. A P-value of less than 0.05 was regarded as significant.

Ethical Issues

In assessing the knowledge of drug- dispensers using simulated client, the drug dispensers were not informed in advance and were not asked for consent to participate in the study. Permission to conduct the study at the selected retail community pharmacies was obtained from Tanzania Food and Drugs Authority. Informed consent was obtained from the pregnant study participants. All information was kept confidential, and none of the participant's responses were reported to the pharmacy owners or hospital management. No names of the drug dispensers or pregnant women were recorded in the checklist or questionnaires, and data were entered into the computer using only study code numbers. The study was granted ethical clearance from Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences Research and Publications Committee.

Results

Assessment of Knowledge of Drug Dispensing Personnel in the Private Community Retail Pharmacies

In total, 200 pharmacies were visited. Out of 200 drug dispensers, 78 (38.8%) were pharmacists, 17 (8.6%) were pharmaceutical technicians, 59 (29.6%) were nurse assistants and 46 (23%) sales persons (without a formal pharmaceutical training).

In 100 pharmacies (scenario 1), drug dispensers were requested to dispense artemether-lumefantrine and sodium valproate, while in the other 100 pharmacies (scenario 2), drug dispensers were requested for captopril and tetracycline. From the first scenario, 43 (43.4%) dispensers were willing to dispense artemether-lumefantrine regardless of the age of pregnancy and 29 (28.9%) were willing to dispense sodium valproate. In the second scenario, 52 (52.3%) drug dispensers were willing to dispense captopril, while 25 (25.2%) were willing to dispense tetracycline.

Out of 200 drug dispensers, 130 (65.1%) enquired about the duration of pregnancy before deciding to dispense the drugs. Twenty-eight (14%) drug dispensers consulted drug inserts and other available literature at the pharmacy. One hundred and twenty-nine (80%) dispensers advised a pregnant woman to consult a gynecologist for advice on the use of drugs during pregnancy.

In comparison, none-pharmaceutical personnel (nurse assistants and sales persons) were more willing to dispense teratogenic drugs than pharmaceutical personnel (pharmacists and pharmaceutical assistants) (P = 0.002). For instance, 22.2% pharmacists, 50% pharmaceutical technicians, 60% nurse assistants and 81% sales persons were willing to dispense captopril during pregnancy. When asked about specific drugs, mostly the pharmacists gave the correct advice. In case of artemether-lumefantrine, most pharmacists (20%) advised that it should be taken after the first trimester. Ten percent (10%) of the pharmacists advised that sodium valproate should not be taken during pregnancy unless benefits outweigh the risk. Twenty-nine percent of the pharmacists advised that methyldopa should be used instead of captopril for the management of hypertensive pregnant women, and amoxicillin should be used to treat infections instead of tetracycline. From this study, it was observed that out of the four teratogenic drugs, majority (74.8%) of the drug dispensers refused to dispense tetracycline and gave the correct reason that it causes teeth discoloration.

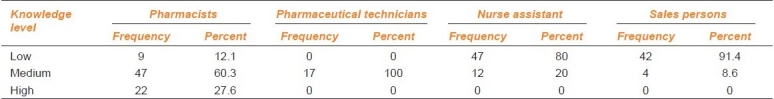

According to the knowledge scale, 99 (49.7%) of the drug dispensers were found to have low knowledge, 80 (39.7%) had a moderate knowledge and 21 (10.6%) had a high knowledge regarding drug use in pregnancy [Table 1]. The level of knowledge correlated with pharmaceutical training and level of education (P = 0.001).

Table 1.

Drug dispensers and their knowledge regarding use of potentially teratogenic drugs during pregnancy (n = 200)

Pregnant Women

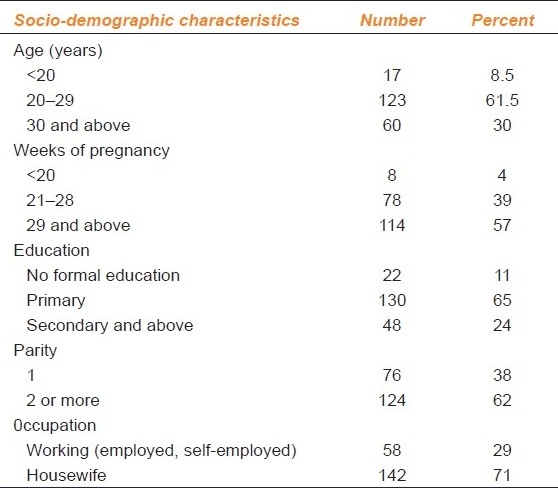

Majority (61.5%) of the 200 pregnant women who were interviewed at the antenatal clinics were in the age group of 20–29 years. About a third (65%) of them had attained primary school education and 71% were housewives. As for the age of pregnancy, 57% were between 29 and 38 weeks of gestation. In terms of parity, 62% pregnant women had already two or more pregnancies during the time of interview [Table 2].

Table 2.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants (pregnant women)

One hundred and thirty-three (66.5%) pregnant women reported that they would hesitate to take medications during pregnancy unless instructed by their physicians. Forty-seven (23.5%) women felt it was safe to take medications during pregnancy, while 123 (61.5%) indicated that it was best to consult a doctor before taking medication during pregnancy. On the other hand, 30 (15%) pregnant women did not have preference on whether to consult the doctor or take medications during pregnancy.

One hundred and fifty-eight (79%) pregnant women reported that they were aware that drugs can be harmful during pregnancy, and 63 (31.5%) were able to mention certain drugs that are known to cause harmful effects during pregnancy. About half (51%) of the pregnant women were aware of certain drugs which are safe to use during pregnancy. Thirty (15%) pregnant women were aware that some antimalarials can be harmful to the fetus, 10 (5%) mentioned some antibiotics which are harmful during pregnancy, 9 (4.5%) mentioned oral contraceptives, and 26 (13%) were aware about the contraindication of some antiepileptic and antihelminthic drugs. Majority of them (68.5%) were not able to mention any drug which is known to cause harmful effects if taken during pregnancy. According to the knowledge scale, 123 (61.8%) women had low knowledge, 70 (35.2%) had moderate knowledge and 6 (3%) had high knowledge regarding drug use during pregnancy. The level of knowledge was found to correlate only with the educational level (P < 0.05).

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to assess the knowledge of drug dispensers and pregnant women on the harmful effects of drug use during pregnancy. The results obtained from this study provide an insight into this. The simulated client methodology used in this study is useful since it involves direct observation, which has a number of strengths as it assesses provider's skills, behavior and knowledge in real time.[16,17]

In this study, it was found that availability of pharmacists in the community retail pharmacies was only 38.8%, an indication that more than half of the drug dispensing personnel in the pharmacies was not professionally trained. The results obtained in the present study are similar to those reported by Damase and his colleagues in which majority (80%) of the drug dispensers referred the pregnant women to a physician.[18] As shown in the present study, drug dispensers do not always give appropriate advice to pregnant women.[18] This can be due to insufficient knowledge.

With respect to provision of pharmaceutical care to pregnant women, pharmacists are more knowledgeable than pharmaceutical technicians, nurse assistants and sales persons. The results show different categories of drug dispensers having different levels of knowledge, with pharmacists having the highest knowledge level followed by pharmaceutical technicians, nurse assistants and sales persons. This is an indication that training is necessary for the dispensing personnel to be able to provide quality pharmaceutical care to patients including pregnant women. It was further observed that differences in the locality influence the type of services provided. It was found that most drug dispensers in pharmacies located within city center area could provide better advice than those in peri-urban areas. These findings are similar to those reported by Rogers et al.,[19] where it was shown that drug dispensers in urban areas provide better pharmaceutical care than those working in the community pharmacies located in rural areas.

Knowledge of pregnant women concerning the harmful effect of drugs is of great significance. Incorrect or insufficient knowledge may lead a pregnant woman to unjustified termination of pregnancy, and there is the likelihood that the fetus may be harmed. On the other hand, there can be several consequences of overestimating the risk of drug use during pregnancy. Nearly 70% of pregnant women in the study conducted by Nordeng et al.[20] chose not to use drugs because they feared they were not safe, an indication that non-compliance may be more common than previously documented.

In the present study, it was found that most of the pregnant women had low knowledge regarding drug use in pregnancy. The level of knowledge was found to correlate only with the educational level. These results are comparable to those reported in a study conducted by Nordeng et al.,[20] which showed that there was a significant association between women's education and their knowledge regarding drug use. In the latter study, less educated women believed that drugs in general were harmful, while women with a higher education were more reluctant to use any medication in pregnancy. In the present study, other variables such as age of pregnant women, weeks of pregnancy and parity did not have significant influence on the knowledge of pregnant women.

It is evident that drug dispensers and pregnant women in the present study have had low knowledge regarding the harmful effects of drugs during pregnancy. Safety in administering medications in pregnancy, as well as the probability of teratogenesis must become the subject of constant sensitization of the female population. Most women who had a low knowledge of drug use during pregnancy were scared to take any medications even if it is a safe drug. Non-compliance during pregnancy is therefore a topic that warrants further investigation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Czeizel AE. The estimation of human teratogenic/fetotoxic risk of exposures to drugs on the basis of Hungarian experience: A critical evaluation of clinical and epidemiological models of human teratology. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2009;8:283–303. doi: 10.1517/14740330902916459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sachdeva P, Patel BG, Patel BK. Drug use in pregnancy: A point to ponder. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2009;71:1–7. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.51941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rohra DK, Das N, Azam SI, Solangi NA, Memon Z, Shaikh AM, et al. Drug-prescribing patterns during pregnancy in the tertiary care hospitals of Pakistan: A cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2008;8:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-8-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrade SE, Raebel MA, Morse AN, Davis RL, Chan KA, Finkelstein JA, et al. Use of prescription medications with a potential for fetal harm among pregnant women. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:546–54. doi: 10.1002/pds.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee E, Maneno MK, Smith L, Weiss SR, Zuckerman IH, Wutoh AK, et al. National patterns of medication use during pregnancy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:537–45. doi: 10.1002/pds.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordeng H, Ystrøm E, Einarson A. Perception of risk regarding the use of medications and other exposures during pregnancy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;66:207–14. doi: 10.1007/s00228-009-0744-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pole M, Einarson A, Pairaudeau N, Einarson T, Koren G. Drug labeling and risk perceptions of teratogenicity: A survey of pregnant Canadian women and their health professionals. J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;40:573–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buurma H, De Smet PA, Egberts AC. Clinical risk management in Dutch community pharmacies: The case of drug-drug interactions. Drug Saf. 2006;29:723–32. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200629080-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toovey S. Malaria chemoprophylaxis advice: Survey of South African community pharmacists′ knowledge and practices. J Travel Med. 2006;13:161–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2006.00035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koren G, Levichek Z. The teratogenicity of drugs for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: Perceived versus true risk. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:S248–52. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.122601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nosten F, White NJ. Artemisinin-based combination treatment of falciparum malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:181–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vajda FJ, Hitchcock AA, Graham J, O′Brien TJ, Lander CM, Eadie MJ. The teratogenic risk of antiepileptic drug polytherapy. Epilepsia. 2010;51:805–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper WO. Clinical implications of increased congenital malformations after first trimester exposures to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008;23:20–4. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000305052.73376.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peterson CK. Tetracycline's effects on teeth preclude uses in children and pregnant or lactating women. Postgrad Med. 1984;76:24–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dashe JS, Gilstrap LC., 3rd Antibiotic use in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1997;24:617–29. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8545(05)70326-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schneider CR, Everett AW, Geelhoed E, Kendall PA, Clifford RM. Measuring the assessment and counseling provided with the supply of nonprescription asthma reliever medication: A simulated patient study. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:1512–8. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiss MC, Booth A, Jones B, Ramjeet S, Wong E. Use of simulated patients to assess the clinical and communication skills of community pharmacists. Pharm World Sci. 2010;32:353–61. doi: 10.1007/s11096-010-9375-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Damase C, Pichereau J, Pathak A, Lacroix I, Montastruc JL. Perception of teratogenic and foetotoxic risk by health professionals: A survey in Midi-Pyrenees area. Pharm Pract. 2008;6:15–9. doi: 10.4321/s1886-36552008000100003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogers A, Hassell K, Noyce P, Harris J. Advice-giving in community pharmacy: Variations between pharmacies in different locations. Health Place. 1998;4:365–73. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(98)00031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nordeng H, Koren G, Einarson A. Pregnant women's beliefs about medications: A study among 866 Norwegian women. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44:1478–84. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]