Abstract

Objectives

Following the measles outbreaks of the late 1980s and early 1990s, vaccination coverage was found to be low nationally, and there were pockets of underimmunized children primarily in inner cities. We described the percentage and demographics of children who were entitled to the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program in 2009 and evaluated whether Healthy People 2010 (HP 2010) vaccination coverage objectives of 90% were achieved among these children.

Methods

We analyzed data from 16,967 children aged 19–35 months sampled by the National Immunization Survey in 2009. VFC-entitled children included children who were (1) on Medicaid, (2) not covered by health insurance, (3) of American Indian/Alaska Native race/ethnicity, or (4) covered by private health insurance that did not pay all of the costs of vaccines, but who were vaccinated at a Federally Qualified Health Center or a Rural Health Center.

Results

An estimated 49.7% of all children aged 19–35 months were entitled to VFC vaccines. Compared with children who did not qualify for VFC, the VFC-entitled children were significantly more likely to be Hispanic or non-Hispanic black; to have a mother who was widowed, divorced, separated, or never married; and to live in a household with an annual income below the federal poverty level. Mothers of VFC-entitled children were significantly less likely to have some college experience or to be college graduates. Of nine vaccines analyzed, two vaccines—polio at 91.7% and hepatitis B at 92.2%—achieved the HP 2010 90% coverage objective for VFC-entitled children, and four others, including measles-mumps-rubella at 88.8%, achieved greater than 80% coverage.

Conclusions

Today, children with demographic characteristics like those of children who were at the epicenter of the measles outbreaks two decades ago are entitled to VFC vaccines at no cost, and have achieved high vaccination coverage levels.

From 1989 to 1991, there was a national resurgence in measles.1 Research revealed that cases observed during the measles resurgence were disproportionately inner-city, preschool-aged American Indian, Hispanic, or black children <5 years of age who had not been vaccinated2–7 and who were living in poverty.1 In response to this resurgence, the Childhood Immunization Initiative8,9 was developed in 1993 to address significant gaps in vaccination coverage among young children in the U.S. Among the strategies for achieving this goal was to eliminate the cost of vaccines as a barrier to being vaccinated. In October 1994, the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program10 was established to achieve this goal by providing financially vulnerable children with publicly purchased vaccines at no cost at the offices and clinics of vaccination providers who are enrolled in the VFC program. Children aged ≤18 years are entitled to receive VFC vaccines if they are (1) not covered by any health insurance that pays for doctor visits and hospital stays (“uninsured”), (2) on Medicaid, (3) of American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) race/ethnicity, or (4) covered by private health insurance that does not cover the costs of all recommended vaccines (“underinsured”) and vaccinated at a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) or a Rural Health Center (RHC). The VFC program is the only federal entitlement program administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The objectives of this article were to (1) describe the percentage of children who were VFC-entitled in 2009, (2) evaluate the extent to which VFC-entitled children were vaccinated by providers authorized to administer VFC vaccines, (3) provide a description of the demographic composition of VFC-entitled children, and (4) evaluate the extent to which Healthy People 2010 (HP 2010) vaccination coverage objectives of 90% for recommended vaccines have not been achieved by VFC-entitled children.

METHODS

The National Immunization Survey

We obtained estimates of vaccination coverage using data from 16,967 children aged 19–35 months sampled by the 2009 National Immunization Survey (NIS).11,12 The NIS begins with a landline telephone survey to identify households with children aged 19–35 months. Data collected in the telephone portion of the National Immunization Survey (NIS) include sociodemographic characteristics about sampled households. Among households with children aged 19–35 months that complete the NIS telephone interview, interviewers request consent to contact age-eligible children's vaccination providers. Among households for which consent is obtained, the NIS sends a mail survey to vaccination providers to obtain sampled children's provider-reported vaccination histories. In 2009, the response rate for the telephone portion of the NIS was 64%. Among the children aged 19–35 months in households that completed the NIS telephone interview, 69% had a sufficiently detailed vaccination history returned from the mail survey sent to vaccination providers to be included in our analyses. We used data from the 2009 NIS Health Insurance Module to determine whether, at the time of the NIS telephone interview, children were entitled to VFC vaccines because they were uninsured, on Medicaid, AI/AN, or underinsured and administered doses at an FQHC or RHC. To determine whether vaccination providers were enrolled in the VFC program to administer VFC vaccines to VFC-entitled children, providers were asked in the mail survey portion of the NIS whether their practice ordered vaccines from their state VFC program.

The recommended vaccination schedule and the HP 2010 vaccination objectives

Vaccines that were recommended for routine administration13 for all of the annual birth cohorts of children who were aged 19–35 months in 2009 included the following: diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis (DTaP), polio, measles-mumps-rubella (MMR), hepatitis B (Hep B), Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), varicella (VAR), heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate (PCV7), hepatitis A (Hep A), and seasonal influenza vaccines.

In this article, we provide estimates of vaccination coverage for ≥4 doses of DTaP, ≥3 doses of polio vaccine, ≥1 dose of MMR, ≥3 doses of Hib, ≥3 doses of Hep B, ≥1 dose of VAR after 12 months of age, ≥4 doses of PCV7, and ≥2 doses of Hep A. For the 2008–2009 seasonal influenza vaccine, two doses were recommended for children who received seasonal influenza vaccine for the first time, or received only one dose the previous influenza season; all other children were recommended to receive one dose.14 We measured influenza vaccination coverage for children vaccinated during September–December of the 2008–2009 influenza season. We provided estimates of vaccination coverage for the U.S. overall and 72 geographic areas, which consist of 63 nonoverlapping geographic areas, including all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and 12 other geographic areas.

HP 2010 established vaccination coverage targets of 90% for each of the individual vaccines listed previously, except for the Hep A and seasonal influenza vaccines.15 Although the Hep A and seasonal influenza vaccines were not included in the original HP 2010 goals, CDC had added them to its annual recommendations by 2009; thus, for this analysis, we chose to evaluate them at the 90% coverage level as with the other vaccines. Estimates with a 95% one-sided upper confidence limit that did not exceed 90% were considered to have failed to achieve the HP 2010 vaccination coverage objective.

RESULTS

Percentage of VFC-entitled children

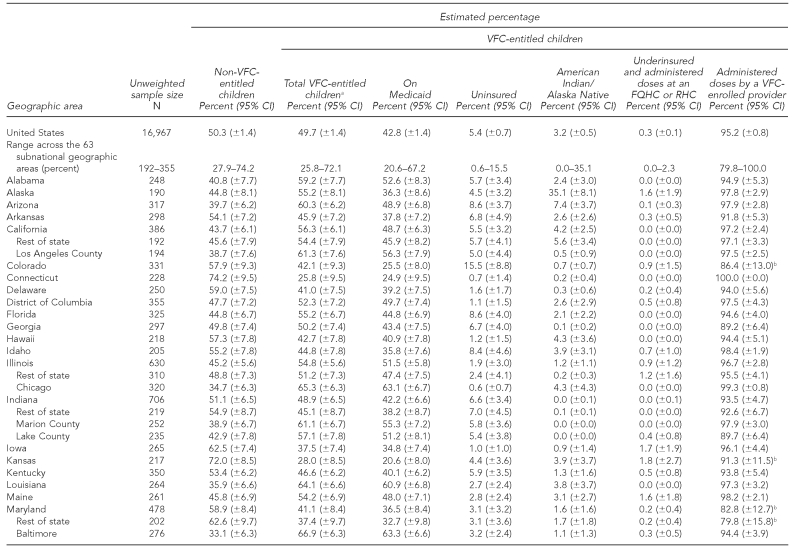

At the time of the NIS telephone interview in 2009, of all children aged 19–35 months, 49.7% (±1.4%) were entitled to VFC vaccines (range: 25.8% to 72.1% among states and substate areas); 42.8% (±1.4%) were on Medicaid (range: 20.6% to ±7.2%); 5.4% (±0.7%) were uninsured (range: 0.6% to 15.5%); 3.2% (±0.5%) were AI/AN (range: 0.0% to 35.1%); and 0.3% (±0.1%) were underinsured and were administered vaccine doses at an FQHC or RHC (range: 0.0% to 2.3%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Estimated percentage of children aged 19–35 months who are VFC-entitled, by geographic area: 2009 National Immunization Survey

aThe sum of the percentage of children who are on Medicaid, uninsured, American Indian/Alaska Native, and underinsured and administered doses at an FQHC or RHC exceeds the percentage of total VFC-entitled children because some children are represented in more than one of these categories.

bEstimates of 95% CI half-widths are >10 percentage points and may be imprecise.

CI = confidence interval

VFC = Vaccines for Children program

FQHC = Federally Qualified Health Center

RHC = Rural Health Center

Percentage of VFC-entitled children vaccinated by VFC-enrolled providers

Nationally, children who were entitled to VFC vaccines were significantly more likely to receive vaccines at VFC-enrolled providers than children who were not VFC-entitled (95.2% vs. 82.1%, p<0.05). Among the states and substate areas, the estimated percentage of VFC-entitled children who were administered vaccines by a VFC-enrolled provider ranged from 79.8% to 100.0%. Among children who were entitled to VFC vaccines, 86.0% (±1.5%) were on Medicaid. Among VFC-entitled children who were not on Medicaid, 77.3% (±4.8%) were uninsured, 19.8% (±4.7%) were AI/AN, and 4.3% (±1.5%) were underinsured and administered doses at an FQHC or RHC.

Among VFC-entitled children who were on Medicaid, 96.1% (±0.8%) received doses from a vaccination provider who was enrolled in the VFC program. Among VFC-entitled children who were uninsured and not on Medicaid, 90.3% (±3.3%) received doses from a vaccination provider who was enrolled in the VFC program. Among AI/AN children, 95.8% (±2.5%) were either on Medicaid, vaccinated at an Indian Health Service facility, or administered doses from a provider who was enrolled in the VFC program. In 2009, 9.3% (±0.7%) of all children aged 19–35 months were covered by private insurance that did not cover all of the costs of vaccines. Among those, only 3.4% (±1.1%) took advantage of their entitlement to VFC vaccines and were administered doses at an FQHC or RHC.

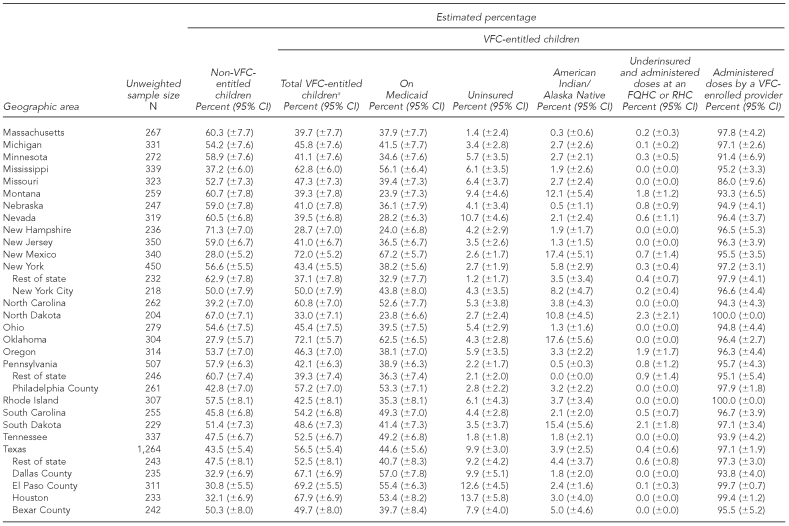

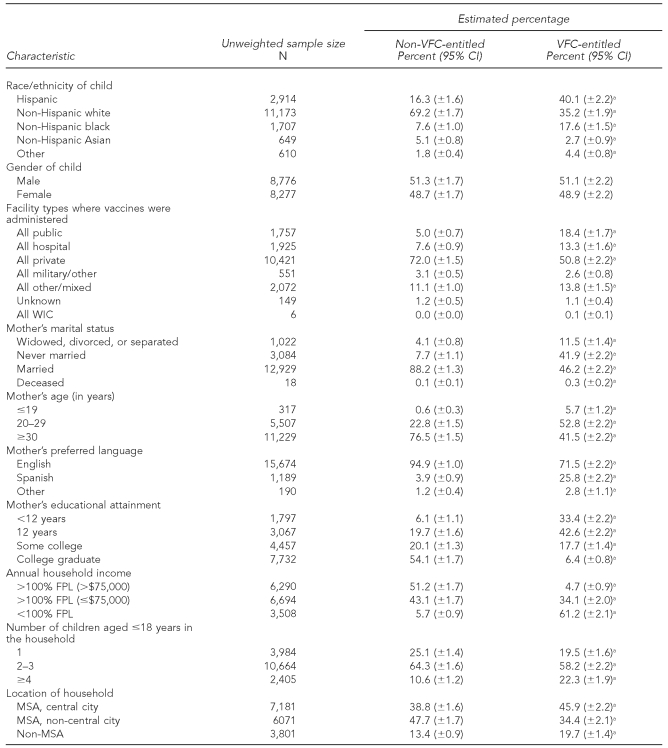

Demographic composition of VFC-entitled children

Compared with children who were not VFC-entitled, children who were VFC-entitled were significantly more likely to be Hispanic or non-Hispanic black, and significantly less likely to be non-Hispanic white or non-Hispanic Asian (Table 2). Also, compared with children who were not VFC-entitled, VFC-entitled children were significantly more likely to have received all of their vaccines at a public clinic and significantly less likely to have received all of their vaccines at a private clinic. However, about 50% of VFC-entitled children received all of their vaccines at a private clinic.

Table 2.

Comparison of VFC-entitled and non-VFC-entitled children by selected demographic characteristics: 2009 National Immunization Survey

aPercentage is significantly different from the percentage in the corresponding group among non-VFC-entitled children (p<0.05).

VFC = Vaccines for Children program

CI = confidence interval

WIC = Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

FPL = federal poverty level

MSA = metropolitan statistical area

Mothers of VFC-entitled children were significantly more likely to be widowed, divorced, separated, or never married and aged ≤29 years; significantly less likely to speak English during the random-digit-dialed portion of the NIS telephone interview; and significantly less likely to have some college experience or to be a college graduate. Finally, compared with children who were not VFC-entitled, children who were VFC-entitled lived in households that were significantly more likely to have annual incomes that were below the federal poverty level, have ≥4 children aged 18 years or younger in the household, or live in a central-city metropolitan statistical area.

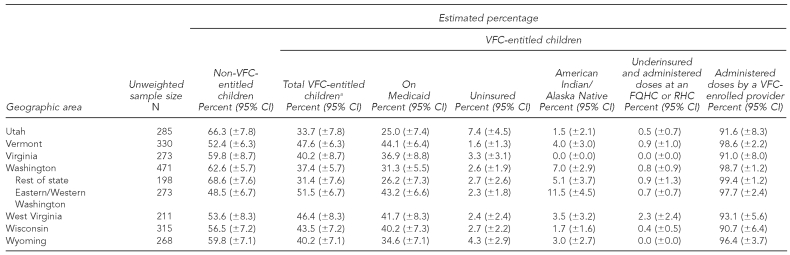

Vaccination coverage for VFC-entitled children and achievement of HP 2010 objectives

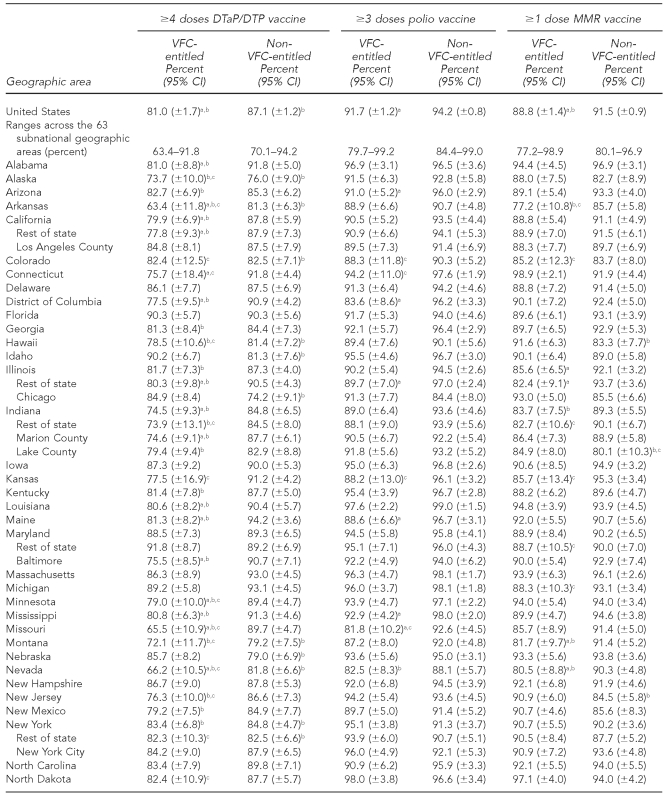

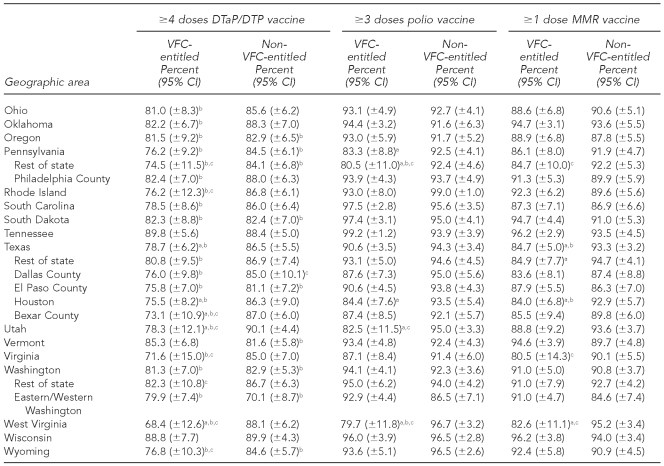

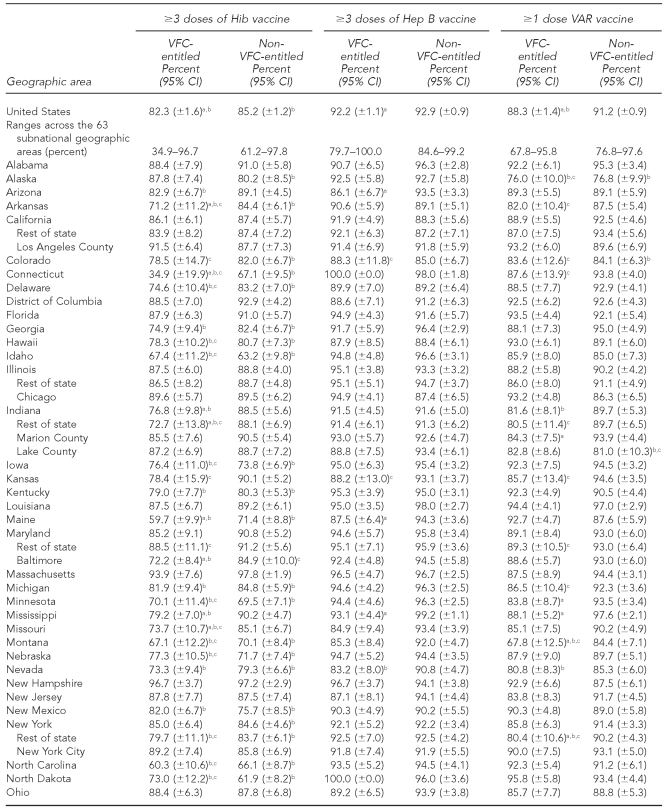

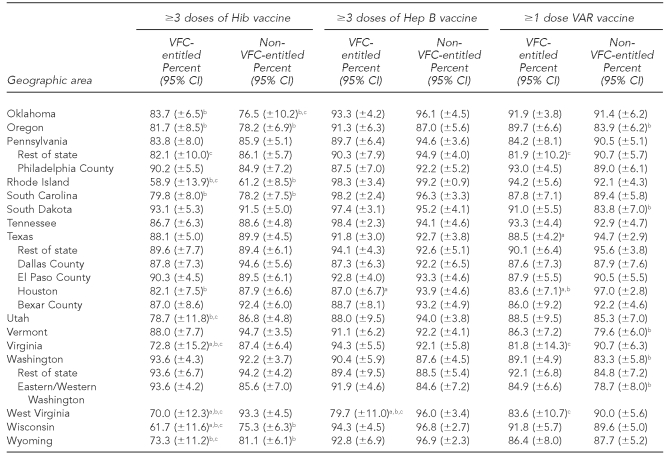

The national estimates of vaccination coverage for DTaP, polio, MMR, Hib, VAR, PCV7, and the seasonal influenza vaccine were significantly lower among VFC-entitled children than for non-VFC-entitled children (Tables 3a–3c). However, the national estimates of vaccination coverage for VFC-entitled children did not fail to achieve the HP 2010 vaccination coverage objective of 90% for the polio and Hep B vaccines.

Table 3a.

Estimated vaccination coverage for selected vaccines—DTaP/DTP, polio, and MMR— by VFC entitlement status and geographic area: 2009 National Immunization Survey

aThe estimate for VFC-entitled children is significantly lower than the estimate for non-VFC-entitled children (p<0.05).

bSignificantly less than the Healthy People 2010 objective of 90% coverage (p<0.05)

cEstimate has 95% CI half-width >10 percentage points and may be imprecise.

DTaP = diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis

DTP = diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis

MMR = measles-mumps-rubella

VFC = Vaccines for Children program

CI = confidence interval

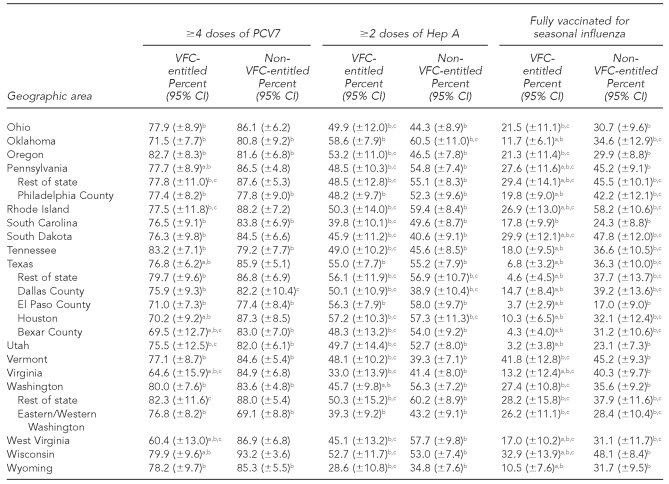

Table 3c.

Estimated vaccination coverage for selected vaccines—PCV7, Hep A, and seasonal influenza—by VFC entitlement status and geographic area: 2009 National Immunization Survey

Note: For the seasonal influenza vaccine, two doses were recommended for children who received seasonal influenza vaccine for the first time, and one dose was recommended for children who were vaccinated for the first time during a previous influenza season.

aThe estimate for VFC-entitled children is significantly lower than the estimate for non-VFC-entitled children (p<0.05).

bSignificantly less than the Healthy People 2010 objective of 90% coverage (p<0.05). (Note: Healthy People 2010 did not include objectives for the Hep A or seasonal influenza vaccines.)

cEstimate has 95% CI half-width >10 percentage points and may be imprecise.

PCV7 = heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate

Hep A = hepatitis A

VFC = Vaccines for Children program

CI = confidence interval

Among the 63 subnational geographic areas listed in Tables 3a–3c, the HP 2010 vaccination coverage objective of 90% was not achieved among VFC-entitled children for 41 (65.1%) areas for DTaP, three (4.8%) areas for polio, four (6.3%) areas for MMR, 33 (52.4%) areas for Hib, two (3.2%) areas for Hep B, five (7.9%) areas for VAR, 51 (81.0%) areas for PCV7, 63 (100.0%) areas for Hep A, and 63 (100.0%) areas for the seasonal influenza vaccine. Among the 63 subnational geographic areas listed in Tables 3a–3c, the HP 2010 vaccination coverage objective of 90% was not achieved among children who were not VFC-entitled for 17 (27.0%) areas for DTaP, zero (0.0%) areas for polio, three (4.8%) areas for MMR, 26 (41.3%) areas for Hib, zero (0.0%) areas for Hep B, seven (11.1%) areas for VAR, 29 areas (46.0%) for PCV7, 63 (100.0%) areas for Hep A, and 63 (100.0%) areas for the seasonal influenza vaccine. Again, it should be noted that the HP 2010 coverage goals did not include objectives for the Hep A or seasonal influenza vaccines, and because these vaccines were more recently added to the -recommended immunization schedule, it is not surprising that all 63 areas failed to achieve 90% coverage for these two vaccines among both VFC-entitled and non-VFC-entitled children.

DISCUSSION

The VFC program had been in place for 16 years as of 2009. The program was designed to provide access to vaccines for financially vulnerable children, and our results suggest that this goal has been achieved for many childhood vaccines.

Approximately half (49.7% ±1.4%) of all children in the U.S. who were aged 19–35 months in 2009 were entitled to VFC vaccines. Our results showed that most VFC-entitled children were on Medicaid, and a high percentage of those children were administered doses from a vaccination provider who was enrolled in the VFC program. All other VFC-entitled children who were on Medicaid but did not receive doses from a provider who was enrolled in the VFC program would have been administered vaccines at no cost through Medicaid's Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment program.16 Also, most of the non-Medicaid VFC-entitled children were uninsured, and a high percentage of those children were administered vaccines by a provider enrolled in the VFC program. Thus, a high percentage of the VFC program's entitled population of financially vulnerable children has received VFC vaccines.

However, we found that approximately 9.3% of all children aged 19–35 months were covered by private insurance that did not cover all of the costs of vaccines, and that among those, only 3.4% took advantage of their entitlement to VFC vaccine and were administered doses at an FQHC or RHC. If more of these children were vaccinated at FQHCs or RHCs, it could boost vaccination rates further.

A child's medical home may be either a private or public practice, such as a health department clinic. Our results showed that approximately half of VFC-entitled children received all of their vaccinations at private providers, and nearly one-fifth received all of their vaccinations at public providers. This result suggests that a large percentage of VFC-entitled children receive their primary care from a provider that serves as the child's medical home. Vaccination coverage among VFC-entitled children who use a medical home consistently has been shown to be essentially equivalent to that of privately insured children who are not VFC-entitled.17

For polio, MMR, Hib, Hep B, and VAR, national estimates of vaccination coverage for VFC-entitled children were within approximately three percentage points of those for non-VFC-entitled children. Thus, gaps in vaccination coverage between VFC-entitled and non-VFC-entitled children are narrow and provide evidence that the VFC program's goal of increasing vaccination coverage by eliminating vaccine cost as a barrier to being vaccinated has succeeded for those vaccines. It is not possible to determine what coverage would be without the VFC program. In 1993, when the Childhood Immunization Initiative was created, only diphtheria-tetanus/diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DT/DTP), poliovirus, MMR, Hib, and Hep B vaccines were recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).18 In 1992, estimated vaccination coverage for all children aged 19–35 months was 59% (±2.9%) for ≥4 doses of DT/DTP, 72.4% (±2.3%) for ≥4 doses of poliovirus, 82.5% (±3.8%) for ≥1 dose of measles-containing vaccine, and 28.2% (±2.7%) for ≥3 doses of Hib; CDC surveillance of vaccination coverage for Hep B had not commenced.19

In 2009, estimated vaccination coverage for these vaccines among non-VFC-entitled children was 87.1% (±1.2%) for DTaP, 94.2% (±0.8%) for polio, 91.5% (±0.9%) for MMR, 85.2% (±1.2%) for Hib, and 92.9% (±0.9%) for Hep B. For children who were VFC-entitled, estimated coverage rates were 81.0% (±1.7%) for DTaP, 91.7% (±1.2%) for polio, 88.8% (±1.4%) for MMR, 82.3% (±1.6%) for Hib, and 92.2% (±1.1%) for Hep B. Among children aged 19–35 months in 2009 who were not VFC-entitled, the HP 2010 vaccination coverage objectives of 90% were not achieved nationally for two out of five of those vaccines. Among 19- to 35-month-old children who were VFC-entitled, the objectives were not achieved for three out of five of the vaccines. It should be noted, however, that for Hib, a recent vaccine shortage may explain the failure to achieve the 90% coverage objective.20 Despite not achieving the 90% coverage objectives for many of these vaccines, the higher coverage rates for both VFC-entitled and non-VFC-entitled children show the great strides that have been made in the last two decades. Further diligence is required so that HP 2020 vaccination coverage goals are achieved for all recommended vaccines.

Limitations

The findings in this article are subject to at least four limitations. First, NIS is a landline telephone survey and does not have data from children who live in households with no telephone service or only cellular phone service. Therefore, our estimates could be biased insofar as households that are not covered by the NIS are different from those covered by the NIS with respect to vaccination coverage. However, recent work suggests that bias in surveys that only sample households with landline telephones may be small.21,22 Second, underestimates of vaccination coverage might have resulted from the exclusive use of provider-reported vaccination histories, because completeness of these records is unknown. Third, in our research, VFC status was measured at the time of the NIS telephone interview. Insofar as some children may have been eligible before that interview, but not at the time of the telephone interview, the percentage of children who had ever been entitled to VFC vaccines may be underestimated. Fourth, ascertainment of provider enrollment in the VFC program from the mail survey to age-eligible children's providers could be imperfect. Mis-measurement of provider enrollment in the VFC program could lead to the underestimation of the percentage of children served by VFC, particularly if clinic staff who provide data on that measurement are not familiar with their state's VFC program.

CONCLUSIONS

The VFC program has grown with the increasing number of vaccines recommended by ACIP. There is no doubt that adhering to the childhood immunization schedule to protect children from vaccine-preventable diseases benefits the health of children. However, the increasing number of recommended vaccines presents major challenges. Moreover, the high cost of recently recommended vaccines has created disincentives for states to contribute additional funds to cover groups of at-risk children not covered by VFC23 and for pediatricians and family physicians to purchase the vaccines for their uninsured patients.24,25 Vaccine costs are only one aspect of this challenge. The unreimbursed non-vaccine costs to private providers of serving VFC-entitled children include those for personnel time for ordering, administering, and recording vaccinations; time for counseling parents; storage equipment; and overhead.26

Because the vast majority of VFC-entitled children are enrolled in the Medicaid program, increasing access of Medicaid-eligible children to primary care providers will be essential to increasing VFC-entitled children's access to vaccines. Substantial effort by state health departments, which administer the VFC program at the state level, and state Medicaid programs will be needed to increase access to immunization providers for VFC-entitled children.

Additional challenges exist beyond giving access to immunization providers. Vaccination records may be scattered across multiple providers, which challenges the ability of any provider to know which vaccines should be offered to a child. Immunization providers should incorporate evidence-based methods to increase vaccination coverage levels of children in their practices.27 Immunization registries can coalesce scattered records and serve as a platform for conducting interventions to improve vaccination coverage levels.28 Evidence-based methods, such as recall and reminder systems, can be expensive to implement, and this expense challenges their widespread adoption.

Provider participation in immunization registries and employment of evidence-based interventions to improve immunization coverage levels are examples of practice expenses that could be supported by the clinical vaccine administration fee. However, administration fees for VFC/Medicaid have been shown to vary widely by state and to be substantially lower than the costs to vaccinate.29 Addressing low administration fees could be essential to enrolling additional immunization providers into VFC/Medicaid and to promoting evidence-based practices that improve vaccination coverage levels.29,30

The VFC program was created to reduce cost as a barrier to vaccination coverage among vulnerable children. Since the advent of the program in 1994, vaccination coverage for recommended vaccines has increased for VFC-entitled children. For the polio and Hep B vaccines, HP 2010 objectives have been achieved for VFC-entitled children. Maintaining or improving coverage levels for the polio and Hep B vaccines and achieving HP 2020 objectives for vaccines that had coverage lower than the HP 2010 goals are important to reduce the burden of vaccine-preventable diseases and to prevent a resurgence of vaccine-preventable diseases among pockets of underimmunized children. Continued partnerships among national, state, local, private, and public entities are needed to sustain these levels and ensure that vaccination programs in the United States remain strong.

Table 3b.

Estimated vaccination coverage for selected vaccines—Hib, Hep B, and VAR— by VFC entitlement status and geographic area: 2009 National Immunization Survey

aThe estimate for VFC-entitled children is significantly lower than the estimate for non-VFC-entitled children (p<0.05).

bSignificantly less than the Healthy People 2010 objective of 90% coverage (p<0.05)

cEstimate has 95% CI half-width >10 percentage points and may be imprecise.

Hib = Haemophilus influenzae type b

Hep B = hepatitis B

VAR = varicella

VFC = Vaccines for Children program

CI = confidence interval

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Measles—United States, 1992. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1993;42(19):378–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkinson WL, Markowitz LE. Measles and measles vaccine. Semin Pediatr Infec Dis. 1991;2:100–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkinson WL, Orenstein WA, Krugman S. The resurgence of measles in the United States, 1989–1990. Annu Rev Med. 1992;43:451–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.43.020192.002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cutts FT, Orenstein WA, Bernier RH. Causes of low preschool immunization coverage in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 1992;13:385–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.13.050192.002125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutchins SS, Escolan J, Markowitz LE, Hawkins C, Kimbler A, Morgan RA, et al. Measles outbreaks among unvaccinated preschool-aged children: opportunities missed by health care providers to administer measles vaccine. Pediatrics. 1989;83:369–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gindler JS, Atkinson WL, Markowitz LE, Hutchins SS. Epidemiology of measles in the United States in 1989 and 1990. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:841–6. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199210000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Measles surveillance—United States, 1991. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1992;41(6):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reported vaccine-preventable diseases—United States, 1993 and the Childhood Immunization Initiative. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1994;43(4):57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Department of Health and Human Services (US). HHS fact sheet, July 6, 2000. Washington: Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. The Childhood Immunization Initiative. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Social Security Online. Compilation of the Social Security laws. Program for distribution of pediatric vaccines: § 1928. [42 U.S.C. 1396s] [cited 2011 Mar 21]. Available from: URL: http://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title19/1928.htm.

- 11.Smith PJ, Battaglia MP, Huggins VJ, Hoaglin DC, Roden A, Khare M, et al. Overview of the sampling design and statistical methods used in the National Immunization Survey. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(4 Suppl):17–24. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00285-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith PJ, Hoaglin DC, Battaglia MP, Khare M, Barker LE. Statistical methodology of the National Immunization Survey, 1994–2002. Vital Health Stat. 2005;2:138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Recommended immunization schedules for persons aged 0 through 18 years— United States, 2009 [published erratum appears in MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009 57(53):1419] MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;57(51&52):Q1–Q4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Influenza vaccination coverage among children aged 6 months–18 years— eight Immunization Information System sentinel sites United States, 2008–09 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(38):1059–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Department of Health and Human Services (US). Healthy people 2010 [conference ed in 2 volumes] Washington: HHS; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Department of Health and Human Services (US),; Health Resources and Services Administration. EPSDT program background. [cited 2010 Jun 14]. Available from: URL: http://www.hrsa.gov/epsdt/overview.htm.

- 17.Smith PJ, Santoli JM, Chu SY, Ochoa DQ, Rodewald LE. The association between having a medical home and vaccination coverage among children eligible for the Vaccines for Children program. Pediatrics. 2005;116:130–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Recommended childhood immunization schedule—United States, 1995. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1995;44(RR-5):1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaccination coverage of 2-year-old children—United States, 1992–1993. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1994;43(15):282–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Licensure of a Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccine (Hiberix) and updated recommendations for use of Hib vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(36):1008–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blumberg SJ, Luke JV. Coverage bias in traditional telephone surveys of low-income and young adults. Public Opin Q. 2007;71:734–49. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blumberg SJ, Luke JV. Reevaluating the need for concern regarding noncoverage bias in landline surveys. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1806–10. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee GM, Santoli JM, Hannan C, Messonnier ML, Sabin JE, Rusinak D, et al. Gaps in vaccine financing for underinsured children in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:638–43. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.6.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freed GL, Cowan AE, Gregory S, Clark SJ. Variation in provider vaccine purchase prices and payer reimbursement. Pediatrics. 2009;124(Suppl 5):S459–65. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1542E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freed GL, Cowan AE, Clark SJ. Primary care physician perspectives on reimbursement for childhood immunizations. Pediatrics. 2009;124(Suppl 5):S466–71. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1542F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birkhead GS, Orenstein WA, Almquist JR. Reducing financial barriers to vaccination in the United States: call to action. Pediatrics. 2009;124(Suppl 5):S451–4. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1542B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Recommendations regarding interventions to improve vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1 Suppl):92–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hinman AR, Ross DA. Immunization registries can be building blocks for national health information systems. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:676–82. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2007.0594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coleman MS, Lindley MC, Ekong J, Rodewald L. Net financial gain or loss from vaccination in pediatric medical practices. Pediatrics. 2009;124(Suppl 5):S472–91. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1542G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindley MC, Shen AK, Orenstein WA, Rodewald LE, Birkhead GS. Financing the delivery of vaccines to children and adolescents: challenges to the current system. Pediatrics. 2009;124(Suppl 5):S548–57. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1542O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]