Abstract

The nonselective muscarinic antagonist scopolamine is known to impair the acquisition of some learning tasks such as inhibitory avoidance. There has been recent research into the effects of this drug in contextual fear conditioning and tone fear conditioning paradigms. The purpose of the present study was to assess the role of the selective M1 muscarinic antagonist dicyclomine in these paradigms and in the inhibitory avoidance test. Rats were administered different doses of dicyclomine or saline 30 min before acquisition training. The animals were tested 24 hr later, and it was observed that 16 mg/kg of dicyclomine impaired both contextual fear conditioning and inhibitory avoidance. However, dicyclomine (up to 64 mg/kg) did not affect tone fear conditioning. These results suggest that the selective M1 muscarinic antagonist dicyclomine differentially affects aversively motivated tasks known to be dependent on hippocampal integrity (such as contextual fear conditioning and inhibitory avoidance) but does not affect similar hippocampus-independent tasks.

Several studies have suggested the involvement of the cholinergic system in learning and memory processes (Bartus et al. 1982; Deutsch 1971; Sen and Battacharya 1991). Anticholinergic drugs, such as the muscarinic antagonist scopolamine, impair the performance of animals in a wide variety of memory tasks (for review, see Fibiger et al. 1991).

Recent studies suggest that the cholinergic system may have an important role in the modulation of Pavlovian fear conditioning in rats. In this type of conditioning, a conditional stimulus (CS), such as a tone, is paired with an unconditional stimulus (UCS), a foot shock, for instance, in a specific context. After a few pairings, the animal begins to present fear-conditioned response when exposed either to the tone or to the same context in which it was trained. It has been demonstrated that hippocampal lesions, before the acquisition session (Kim and Fanselow 1992; Phillips and LeDoux 1992) or 24 hours later (Kim and Fanselow 1992; Anagnostaras et al. 1999a), impair contextual fear conditioning but do not interfere with conditioning to a discrete stimulus such as a tone. Amygdala lesions, however, affect the acquisition of both kinds of conditioning (Phillips and LeDoux 1992; Maren et al. 1996).

An effect similar to that observed with hippocampal lesions was obtained by Anagnostaras et al. (1995, 1999b) after systemic administration of scopolamine before training, that is, an effect of impairment of contextual fear conditioning but no effect in tone fear conditioning. However, no effect was observed with posttraining scopolamine administration. Therefore, the authors suggest that only the pretraining administration of scopolamine appears to be capable of reproducing the effects of hippocampal lesions. Rudy (1996), however, observed that systemic injection of scopolamine, before or up to 3 hours after training, impairs tone conditioning in addition to hindering contextual conditioning. On the other hand, Young et al. (1995) observed that treatment with this substance before training hindered the acquisition of tone fear conditioning without interfering with contextual fear conditioning.

Some authors have already used inhibitory (passive) avoidance as a measurement of contextual conditioning (Selden et al. 1991; Bueno et al. 1993; Oliveira et al. 1998). The passive avoidance response, like contextual conditioning, depends on the integrity of the amygdala (Blanchard and Blanchard 1972; Grossman et al. 1975; Nagel and Kemble 1976) and of the hippocampus (O'Keefe and Nadel 1978; Gray 1982) and may be affected by the administration of cholinergic antagonists (for review, see Bammer 1982). In general, pretraining scopolamine treatment impairs the acquisition of the passive avoidance response, an effect that is unlikely to be related to state-dependent learning (Meyers 1965; Elrod and Buccafusco 1988; Quirarte et al. 1994). These results suggest an influence of the cholinergic system on emotional memory; however, because scopolamine lacks receptor specificity, it is difficult to determine which of the muscarinic receptors would be primarily involved in its action on this type of learning. Four types of muscarinic receptors are known, named M1 to M4 (Waelbroeck et al. 1990), and five subtypes of muscarinic receptors have been cloned and designated m1 to m5 (for review, see Hulme et al. 1990). It has been demonstrated that the M1 receptor subtype predominates in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus (Levey et al. 1991; Wei et al. 1994), areas in which cholinergic transmission appears to be essential to learning and memory processes. Moreover, blockade by the selective M1 receptor antagonist pirenzepine impairs learning of hippocampal-dependent tasks like delayed nonmatching to position (Aura et al. 1997) and delayed matching to position (Andrews et al. 1994) as well as working memory (Sala et al. 1991), spatial memory (Hagan et al. 1987; Hunter and Roberts 1988), and representational memory (Messer et al. 1990) tests.

The passive avoidance test can be affected by either systemic (Worms et al. 1989) or central injections (Ohnuki and Nomura 1996; Caufield et al. 1983) of pirenzepine, administered before the acquisition session. Roldán et al. (1997) showed that systemic administration of the M1 antagonists biperidine and trihexyphenidyl impairs the consolidation of the passive avoidance response in a dose-dependent manner, suggesting a critical influence of M1 receptor subtype in this kind of learning. Another compound, dicyclomine, which was shown to have a high affinity to the M1 muscarinic receptor (Giachetti et al. 1986), also impairs passive avoidance learning in mice when administered immediately after training. This effect was reversed by pretreatment with PG-9, a presynaptic cholinergic amplifier (Ghelardini et al. 1988). Recently, Ghelardini and coworkers (1999) observed that inactivation of the M1 gene hinders the acquisition of the passive avoidance response in mice, evidencing the importance of M1 receptor integrity for this type of task. Despite all this, as far as we know, there are no studies that examine the effect of selective M1 antagonists on classical fear conditioning.

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of a M1 selective antagonist, dicyclomine, on the acquisition of emotional memory, evaluated by the following tests: inhibitory avoidance, classical fear conditioning to a discrete stimulus (tone conditioning), and contextual fear conditioning.

RESULTS

Contextual Conditioning

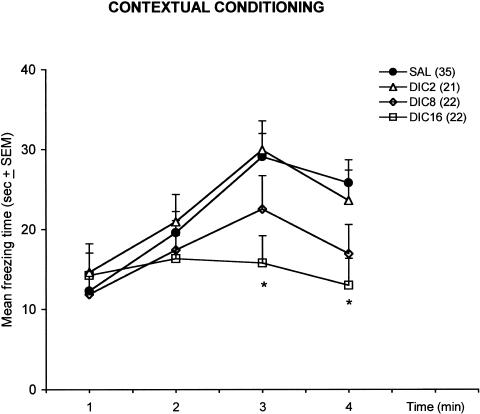

The higher dose of dicyclomine used (16 mg/kg) impaired the acquisition of the contextual conditioning (Fig. 1). There was a significant Minute effect (F(3,288) = 14.95; p < .0001) and a significant interaction between the test Minute and Treatment (F(9,288) = 2.12; p = .02). The post hoc test showed that animals injected with 16 mg/kg of dicyclomine showed significantly less freezing than saline-injected controls during the last two minutes of the test (p < .05). The main effect of Treatment was not significant (F(3,93) = 2.02; p = .11).

Figure 1.

Effects of dicyclomine (2, 8, and 16 mg/kg) on the freezing response of rats in the contextual conditioning test. DIC2, dicyclomine 2 mg/kg; DIC8, dicyclomine 8 mg/kg; DIC16, dicyclomine 16 mg/kg; SAL, saline. The number of animals per group is shown in parentheses after the group names; *p < .05 compared to SAL.

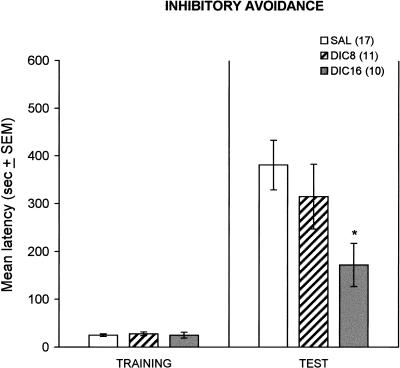

Inhibitory Avoidance

The same dose that impaired the contextual conditioning also impaired the inhibitory avoidance test. For the test latency, one-way ANOVA showed significant differences between Treatments (F(2,35) = 3.38; p = .04). The post hoc test showed that animals injected with 16 mg/kg of dicyclomine showed a significant decreased latency compared to saline-injected controls (Fig. 2). The group injected with 8 mg/kg of dicyclomine did not differ from other groups (Fig. 2). Dicyclomine did not affect training latencies (F(92,35) = 0.21; p = .8).

Figure 2.

Effects of dicyclomine (8 and 16 mg/kg) on the latency to enter the black compartment during one trial training and retention test of the inhibitory avoidance task. DIC8, dicyclomine 8 mg/kg; DIC16, dicyclomine 16 mg/kg; SAL, saline. The number of animals per group is shown in parentheses after the group names; *p < .05 compared to SAL.

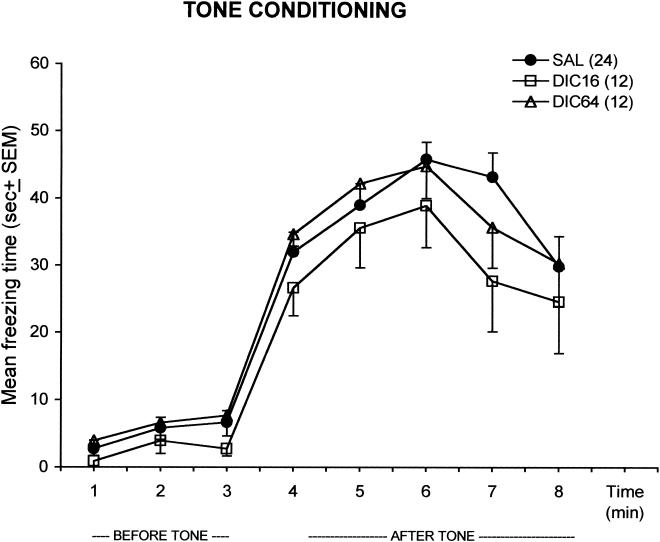

Tone Conditioning

As can be seen in Figure 3, dicyclomine did not affect conditioning to the tone. The main effect of Minute was significant (F(7,315) = 73.47; p < .00001). Post hoc analyses with the test of Tukey indicated that all groups displayed more freezing behavior after tone presentation (p < .05). There was no interaction between Minute and Treatment (F(14,315) = 0.59; p = .86). The main effect of Treatment was also not significant (F(2,45) = 1.56; p = .219).

Figure 3.

Effects of dicyclomine (16 and 64 mg/kg) on the freezing response of rats in the tone conditioning test before and after tone. DIC16, dicyclomine 16 mg/kg; DIC64, dicyclomine 64 mg/kg; SAL, saline. The number of animals per group is shown in parentheses after the group names.

DISCUSSION

The main findings of the present study are that treatment with 16 mg/kg of dicyclomine, an M1 selective antagonist, impairs contextual fear conditioning and reduces retention latency of animals submitted to the inhibitory avoidance test. However, the acquisition of tone fear conditioning was not affected, even with a dicyclomine dose four times higher (64 mg/kg).

There are several reports showing the effect of the nonselective muscarinic antagonist scopolamine on classical fear conditioning tests (tone and contextual conditioning). For instance, Anagnostaras and coworkers (1995, 1999b) obtained impairment on the acquisition of contextual, but not tone fear conditioning, following systemic pretraining administration of moderate doses of this substance. However, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports of the effects of selective M1 antagonists on these same tests. The effects of dicyclomine pretreatment reported here were similar to those obtained by Anagnostaras et al. (1995, 1999b).

Regarding the inhibitory avoidance task, our results are in accordance with previous studies which demonstrate that pretraining administration of scopolamine (Meyers 1965; Erold and Buccafusco 1988) or of the M1 selective antagonist pirenzepine (Caulfield et al. 1983; Ohnuki and Nomura 1996) impairs the acquisition of inhibitory avoidance response in mice. Recently, Ghelardini and coworkers (1998) observed that administration of dicyclomine immediately after training impairs the inhibitory avoidance response in mice. The same authors also showed that inactivation of the M1 receptor gene in mice produces anterograde amnesia in the inhibitory avoidance test (Ghelardini et al. 1999).

In the present study, dicyclomine mimicked the effects of moderate doses of scopolamine in tests for inhibitory avoidance and contextual fear conditioning, because this selective antagonist affected the inhibitory avoidance response in the same dose range as that which affects the contextual conditioned freezing, suggesting the participation of M1 receptors in these two types of tasks. Both tasks are also affected by hippocampal lesions (Gray 1982; Kim and Fanselow 1992; Phillips and LeDoux 1992). Hence, these data suggest that inhibitory avoidance and contextual fear conditioning present some common component related to the hippocampal function. It has been demonstrated that the M1 receptor subtype predominates in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus (Levey et al. 1991) and that selective M1 agonists exhibit the capacity to augment NMDA receptor function in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells (Rouse et al. 1999). An M1 receptor subtype-induced augmented function of NMDA receptors in the hippocampus may be involved in the process of learning an inhibitory avoidance task and contextual fear conditioning.

On the other hand, it is claimed that scopolamine, as well as electrolytic hippocampal lesion, produces motor hyperactivity leading to an impaired exploration, which may be responsible for deficits in contextual representation (Anagnostaras et al. 1999a, Maren et al. 1997). One possibility is that dicyclomine increases motor activity in the same way scopolamine does. We can not preclude this possibility at the moment, although it seems to be unlikely in the present situation, since the animals explored the environment in a drug-free state during the 5-min familiarization session.

The function of muscarinic receptors in the classical fear conditioning to a discrete stimulus, such as a tone, is not yet clear. Rudy (1996) observed that administration of scopolamine to juvenile rats affected acquisition and consolidation in both types of conditioning (contextual and tone conditioning). Using the same dose range, Anagnostaras et al. (1995) obtained an impairment of contextual, but not tone conditioning, after pretraining administration of scopolamine to mature rats. Recently, Anagnostaras et al. (1999b) observed that treatment with a very high dose of scopolamine (100 mg/kg) before training affected the tone fear conditioning test. In the present study, however, not even the highest dicyclomine dose (64 mg/kg) was capable of interfering with tone conditioning. A role for the M1 receptor is not possible to discard, as we did not test still higher doses, unlike Anagnostaras et al. (1999b), who used a dose 10 times higher than that which impaired contextual conditioning, whereas we only used a dose 4 times higher. It is, however, questionable whether extremely high doses maintain specificity to the M1 receptor.

M1 receptors were also found in the rat amygdala (Levey et al. 1991). Amygdala lesions affect both contextual and tone conditioning tasks (Blanchard and Blanchard 1972; Nagel and Kemble 1976; Phillips and LeDoux 1992). However, as observed by Anagnostaras et al. (1999b) and supported by the present results, blockade of cholinergic transmission produces effects that are different from those observed with amygdala lesion. On the other hand, our results were very similar to those produced by hippocampal lesion (Kim and Fanselow 1992; Phillips and LeDoux 1992). It is, therefore, possible that the hippocampal function is more susceptible to disruption caused by cholinergic manipulations than is the amygdala. Alternatively, other muscarinic receptors, beside the M1 receptor, may be involved in the acquisition of amygdala-dependent fear conditioning.

In the present study, treatment with M1 muscarinic antagonist was carried out 30 min before the conditioning session; therefore, all animals were trained under the influence of dicyclomine. Nonetheless, they were tested in an “off-drug” state because the three tasks were tested only 24 hr after training, raising the possibility of state-dependent learning. However, no state-dependent learning using scopolamine is observed either on the inhibitory avoidance task (Elrod and Buccafusco 1988) or on the contextual conditioned freezing (Anagnostaras et al. 1999b). Yet, the possibility of state-dependent learning cannot be ruled out. This possibility, however, would be interesting per se because it would show that state-dependent learning can be selective, occurring in some (inhibitory avoidance and contextual fear conditioning) but not in other tasks (tone fear conditioning). Although administered 30 min before training, the drug is present both when training occurs and during the temporal interval that immediately follows the training session. Thus, it is not possible to decide whether dicyclomine is affecting encoding or consolidation. More studies are needed to solve these issues.

It is well known that in classical fear conditioning, administration of a substance before training may impair conditioning by interfering with shock sensitivity. Based on the present results, it is unlikely that dicyclomine had interfered in any way with the UCS processing. If this had occurred, the same pattern of effects would be expected for all the tests performed, which was not the case. Moreover, Bartolini and coworkers (1992) demonstrated that systemic administration of dicyclomine, both in rats and mice, blocks the analgesia induced by M1 selective agonists, McN-A-343 and AF-102B, but does not present any effect per se on the animal's pain threshold. It is, therefore, unlikely that dicyclomine had interfered with the sensitivity of animals to shock.

In conclusion, the selective M1 muscarinic antagonist dicyclomine differentially affected aversively motivated tasks known to be dependent on hippocampal integrity (such as contextual fear conditioning and inhibitory avoidance), but did not impair similar tasks that are independent of the hippocampus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Wistar male rats, 3–4 months old (340–510 g of body weight), bred and raised in the animal facility of the Department of Psychobiology of UNIFESP/EPM, were used. Animals were maintained under controlled temperature (23 ± 2°C) and 12:12-h light–dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 a.m. ) conditions. Rat chow and tapwater were provided ad libitum. Each behavioral test was conducted in separate groups of animals.

Apparatus

The inhibitory avoidance apparatus consisted of two compartments, each measuring 22 × 21 × 22 cm, connected by a sliding door. The walls of the safe compartment were white, whereas the other compartment, where the animals received foot shock, had black walls with visual patterns (2 squares measuring 5.5 × 5.5 cm and 3 squares measuring 4.0 × 4.0 cm made of white cardboard). The tops of both compartments were covered with transparent acrylic. The floor consisted of a metal grid (0.4 cm-diameter rods placed 1.2 cm apart from each other) connected to a shock generator and control module (Ugo Basile model 7551), by which foot shocks of 1 mA and 1 second long could be delivered. For the tone conditioning test, a white cylindrical chamber, diameter 35 cm and height 60 cm, was used. The apparatuses were kept in different rooms. A buzzer placed outside the inhibitory avoidance apparatus or the cylindrical chamber produced an 80-dB tone, used as the CS.

Drug

Dicyclomine chloride (Sigma Chemical Co) was dissolved in 0.9% saline and injected, i.p., in a volume of 1.0 ml/kg. The doses used were 2, 8, 16, and 64 mg/kg. Preparation of the highest dose required heating the drug to 40°C for 10 min to make it soluble and placing it in a waterbath at 30°C to avoid precipitation of the salt.

Behavioral Procedures

Contextual Conditioning

The test was carried out during three consecutive days. On the first day (familiarization), the animals were individually placed in the black compartment of the avoidance apparatus, with the sliding door closed, where they remained for 5 min. After this period, the animals were removed from the apparatus and returned to their homecages. On the second day (training), the animals received either saline or dicyclomine (2, 8, or 16 mg/kg) and 30 min later were again individually confined in the black compartment of the avoidance box. Two min later, the CS, 5 s long, sounded, and in the last second a foot shock (UCS) was delivered, which finished together with the tone. The tone–foot-shock pairing was repeated five times, 30 s apart. Thirty seconds after the last foot shock, the animal was removed from the apparatus. The contextual conditioning test was performed on the third day, 24 h after the training. Each animal was placed in the same training context, that is, directly inside the dark compartment of the avoidance apparatus. The sliding door remained closed and no stimulus (tone or foot shock) was delivered. The freezing time—defined as complete immobility of the animal, with the absence of vibrissae movements and sniffing (Bouton and Bolles 1980)—was recorded minute by minute during 4 min.

Inhibitory Avoidance

The rats received either a saline or dicyclomine (8 or 16 mg/kg) injection and, 30 min later, were placed, individually, inside the light compartment (safe side) of the avoidance apparatus. Ten seconds later the door was opened, and, as soon as the animal entered the black compartment with all four paws, the door was closed and 5 foot shocks (1 mA, 1 s) were delivered at 30-s intervals. The latency for the animal to enter the black compartment was recorded. Thirty seconds after the last foot shock the animal was removed from the apparatus. The test was carried out 24 h after training. Each animal was placed again in the light compartment of the avoidance apparatus, and, 10 s later, the door was opened and the time taken by the animal to cross to the black compartment (four paws in) was recorded (test latency). If the animal did not cross within 540 s, it was removed from the apparatus and a latency of 540 s was attributed. No foot shock was delivered during the test.

Tone Conditioning

Tone conditioning was carried out for three consecutive days, in exactly the same way as contextual conditioning, except that on the third day, each animal was placed in the cylindrical chamber (new context), where it remained for 8 min. During the fourth minute of exposure to the apparatus, the CS was presented 5 times at 30-s intervals, beginning at the end of the third minute. The freezing time was measured, minute by minute, during the first 3 min (before the tone) and during the final 5 min (after the tone).

The pharmacological treatment was done 30 min before training, and the doses employed were 16 and 64 mg/kg of dicyclomine. The dose of 16 mg/kg was chosen because it was effective in impairing both contextual conditioning and inhibitory avoidance learning.

Statistical Analysis

Data from the classical fear conditioning (contextual as well as tone conditioning) were analyzed by a two-way ANOVA for repeated measures with Treatment and Minute as main factors. When applied, the analysis was followed by the Tukey honest significant difference test. The data from the inhibitory avoidance were analyzed by a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey when necessary.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by AFIP and FAPESP. We thank Orlando F.A. Bueno for helpful comments and criticisms and Deborah Suchecki for translating the manuscript.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL mgabi@psicobio.epm.br; FAX 5511-5572-5092.

Article and publication are at www.learnmem.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/lm.34900.

REFERENCES

- Anagnostaras SG, Maren S, Fanselow MS. Scopolamine selectively disrupts the acquisition of contextual fear conditioning in rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1995;64:191–194. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1995.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Temporally graded retrograde amnesia of contextual fear after hippocampal damage in rats: Within-subjects examination. J Neurosci. 1999a;19:1106–1114. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-03-01106.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostaras SG, Maren S, Sage JR, Goodrich S, Fanselow MS. Scopolamine and Pavlovian fear conditioning in rats: Dose-effect analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999b;21:731–744. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JS, Jansen JH, Linders S, Princen A. Effects of disrupting the cholinergic system on short-term spatial memory in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1994;115:485–494. doi: 10.1007/BF02245572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aura J, Sirvio J, Riekkinen P., Jr Methoctramine moderately improves memory but pirenzepine disrupts performance in delayed non-matching to position test. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;333:129–134. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bammer G. Pharmacological investigations of neurotransmitter involvement in passive avoidance responding: A review and some new results. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1982;6:247–296. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(82)90041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolini A, Ghelardini C, Fantetti L, Malcangio M, Malmberg-Aiello P, Giotti A. Role of muscarine receptor subtypes in central antinociception. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;105:77–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartus RT, Dean RL, Beer B, Lippa AS. The cholinergic hypothesis of geriatric memory dysfunction. Science. 1982;217:408–417. doi: 10.1126/science.7046051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard DC, Blanchard RJ. Innate and conditioned reactions to threat in rats with amygdaloid lesions. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1972;81:281–290. doi: 10.1037/h0033521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Bolles RC. Conditioned fear assessed by freezing and by the suppression of three different baselines. Anim Learn Behav. 1980;8:429–434. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno OFA, Oliveira MGM, Pomarico AC, Gugliano EB. A dissociation between the proactive ECS effects on inhibitory avoidance learning and on classical fear conditioning. Behav Neural Biol. 1993;59:180–185. doi: 10.1016/0163-1047(93)90938-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield MP, Higgins GA, Straughan DW. Central administration of the muscarinic receptor subtype-selective antagonist pirenzepine selectively impairs passive avoidance learning in the mouse. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1983;35:131–132. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1983.tb04290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch JA. The cholinergic synapse and the site of memory. Science. 1971;174:788–794. doi: 10.1126/science.174.4011.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrod K, Buccafusco JJ. An evaluation of the mechanism of scopolamine-induced impairment in two passive avoidance protocols. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1988;29:15–21. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90267-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fibiger HC, Damsma G, Day JC. Behavioral pharmacology and biochemistry of central cholinergic neurotransmission. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1991;295:399–414. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-0145-6_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghelardini C, Galeotti N, Gualtieri F, Marchese V, Bellucci C, Bartolini A. Antinociceptive and antiamnesic properties of the presynaptic cholinergic amplifier PG-9. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284:806–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghelardini C, Galeotti N, Matucci R, Bellucci C, Gualtieri F, Capaccioli S, Quattrone A, Bartolini A. Antisense “knockdowns” of M1 receptors induces transient anterograde amnesia in mice. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:339–348. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00194-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giachetti A, Giraldo E, Ladinsky H, Montagna E. Binding and functional profiles of the selective M1 muscarinic receptor antagonists trihexyphenidyl and dicyclomine. Brit J Pharmac. 1986;89:83–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1986.tb11123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray J. The Neuropsychology of Anxiety. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman SP, Grossman L, Walsh L. Functional organization of the rat amygdala with respect to avoidance behavior. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1975;88:829–850. doi: 10.1037/h0076396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan JJ, Jansen JH, Broekkamp CL. Blockade of spatial learning by the M1 muscarinic antagonist pirenzepine. Psychopharmacology. 1987;93:470–476. doi: 10.1007/BF00207237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme EC, Birdsall NJM, Buckley NJ. Muscarinic receptor subtypes. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1990;30:633–673. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.30.040190.003221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter AJ, Roberts FF. The effect of pirenzepine on spatial learning in the Morris Water Maze. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1988;30:519–523. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90490-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, Fanselow MS. Modality-specific retrograde amnesia of fear. Science. 1992;256:675–677. doi: 10.1126/science.1585183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levey AI, Kitt C, Simonds W, Price D, Brann MR. Identification and localization of muscarinic receptor subtype proteins in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1991;11:3218–3226. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03218.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S, Aharonov G, Fanselow M S. Retrograde abolition of conditional fear after excitotoxic lesions in the basolateral amygdala of rats: Absence of a temporal gradient. Behav Neurosci. 1996;110:718–726. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.110.4.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Neurotoxic lesions of the dorsal hippocampus and Pavlovian fear conditioning in rats. Behav Brain Res. 1997;88:261–274. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer WS, Jr, Bohnett M, Stibbe J. Evidence for a preferential involvement of M1 muscarinic receptors in representational memory. Neurosci Lett. 1990;116:184–189. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90407-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers B. Some effects of scopolamine on a passive avoidance response in rats. Psychopharmacologia. 1965;8:111–119. doi: 10.1007/BF00404171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel JA, Kemble ED. Effects of amygdaloid lesions on the performance of rats in four passive avoidance tasks. Physiol Behav. 1976;17:245–250. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(76)90072-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnuki T, Nomura Y. Effects of selective muscarinic antagonists, pirenzepine and AF-DX 116, on passive avoidance tasks in mice. Biol Pharmacol Bull. 1996;19:814–818. doi: 10.1248/bpb.19.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe J, Nadel L. The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira MG, Bueno OFA, Gugliano E. Anterograde effects of a single electroconvulsive shock on inhibitory avoidance and on cued fear conditioning. Brazil J Med Biol Res. 1998;31:1091–1094. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x1998000800009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips RG, LeDoux JE. Differential contribution of amygdala and hippocampus to cued and contextual fear conditioning. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106:274–285. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirarte GL, Cruz-Morales S E, Cepeda A, Garcia-Montañez M, Roldán-Roldán G, Prado RA. Effects of central muscarinic blockade on passive avoidance: Anterograde amnesia, state dependency, or both? Behav Neural Biol. 1994;62:15–20. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(05)80054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roldán G, Bolaños-Badillo E, González-Sánchez H, Quirarte GL, Prado-Alcalá RA. Selective M1 muscarinic receptor antagonists disrupt memory consolidation of inhibitory avoidance in rats. Neurosci Lett. 1997;230:93–96. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00489-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse ST, Marino MJ, Potter LT, Conn PJ, Levey A. Muscarinic receptor subtypes involved in hippocampal circuits. Life Sci. 1999;64:501–509. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00594-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudy JW. Scopolamine administered before and after training impairs both contextual and auditory-cue fear conditioning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1996;65:73–81. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1996.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala M, Braida D, Calcaterra P, Leone MP, Comotti FA, Gianola S, Gori E. Effect of centrally administered atropine and pirenzepine on radial arm maze performance in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991;194:45–49. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selden NRW, Everitt BJ, Jarrard LE, Robbins TW. Complementary roles for the amygdala and hippocampus in aversive conditioning to explicit and contextual cues. Neuroscience. 1991;42:335–350. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90379-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen AP, Bhattacharya SK. Effect of selective muscarinic receptor agonists and antagonists on active-avoidance learning acquisition in rats. Indian J Exp Biol. 1991;29:136–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waelbroeck M, Tastenoy M, Camus J, Christophe J. Binding of selective antagonists to four muscarinic receptors (M1-M4) in rat forebrain. Mol Pharmacol. 1990;38:267–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J, Walton EA, Milici A, Buccafusco JJ. m1–m5 musarinic receptor distribution in rat CNS by RT-PCR and HPLC. J Neurochem. 1994;63:815–821. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63030815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worms P, Gueudet C, Perio A, Soubrie P. Systemic injection of pirenzepine induces a deficit in passive avoidance learning in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1989;98:286–288. doi: 10.1007/BF00444707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SL, Bohenek DL, Fanselow MS. Scopolamine impairs acquisition and facilitates consolidation of fear conditioning: Differential effects for tone vs context conditioning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1995;63:174–180. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1995.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]