Abstract

Experimental traumatic brain injury (TBI) studies report the neuroprotective effects of female sex steroids on multiple mechanisms of injury, with the clinical assumption that women have hormonally mediated neuroprotection because of the endogenous presence of these hormones. Other literature indicates that testosterone may exacerbate injury. Further, stress hormone abnormalities that accompany critical illness may both amplify or blunt sex steroid levels. To better understand the role of sex steroid exposure in mediating TBI, we 1) characterized temporal profiles of serum gonadal and stress hormones in a population with severe TBI during the acute phases of their injury; and 2) used a biological systems approach to evaluate these hormones as biomarkers predicting global outcome. The study population was 117 adults (28 women; 89 men) with severe TBI. Serum samples (n=536) were collected for 7 days post-TBI for cortisol, progesterone, testosterone, estradiol, luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). Hormone data were linked with clinical data, including acute care mortality and Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) scores at 6 months. Hormone levels after TBI were compared to those in healthy controls (n=14). Group based trajectory analysis (TRAJ) was used to develop temporal hormone profiles that delineate distinct subpopulations in the cohort. Structural equations models were used to determine inter-relationships between hormones and outcomes within a multivariate model. Compared to controls, acute serum hormone levels were significantly altered after severe TBI. Changes in the post-TBI adrenal response and peripheral aromatization influenced hormone TRAJ profiles and contributed to the abnormalities, including increased estradiol in men and increased testosterone in women. In addition to older age and greater injury severity, increased estradiol and testosterone levels over time were associated with increased mortality and worse global outcome for both men and women. These findings represent a paradigm shift when thinking about the role of sex steroids in neuroprotection clinically after TBI.

Key words: global outcome, group based trajectory analysis, sex steroids, structural equations model, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

At least 5.3 million people in the United States currently require long-term or life-long assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs) as a result of traumatic brain injury (TBI) (Faul et al., 2010). Men have a higher incidence of TBI than women, with reported incidence ratios ranging from 2.0:1 to 2.8:1 and mortality ratios of 3.5:1 (Thurman et al., 1999). The clinical literature is mixed regarding the influence of sex on recovery and outcome. In studies that include mild TBI in at least a portion of the population, women have poorer outcomes. Other studies implicate female sex and menopausal status as both a risk and a protective factor depending upon the cohort studied (Berry et al., 2009; Farace et al., 2000; Farin and Marshall, 2004; Ottochian et al., 2009; Wagner and Sasser , 2000).

Although a significant portion of the population with TBI are women, the majority of the clinical and animal research on TBI to date has been with men. However, there are a growing number of studies using experimental injury models that report neuroprotection with female gonadal hormones. A number of review articles have evaluated this body of literature (Hurn et al., 2000; Mendelowitsch et al., 2001; Roof and Hall, 2000 a,b; Stein, 2001; Stein et al., 2008). Data implicate estradiol as an agent that can ameliorate excitotoxicity, promote neuronal lactate utilization, maintain cerebral blood flow, and decrease apoptosis in central nervous system (CNS) injury models. Decades of research also suggest that progesterone, along with its major metabolite allopregnanolone, has powerful effects on cerebral edema. Other reports suggest that progesterone reduces neuroinflammation, blood–brain barrier disruption, and oxidative injury. To date, two clinical studies demonstrate that treatment with pharmacological doses of progesterone is safe and can be beneficial toward recovery in patients with moderate to severe TBI (Wright et al., 2007; Xiao et al., 2008).

These and other findings have led many to the clinical assumption that women have more hormonally mediated neuroprotection because of the endogenous circulation of sex hormones at the time of injury. However, up to 80% of patients with significant TBI have some type of acute pituitary dysfunction and related hypogonadism, and up to 25% of long-term survivors continue to have pituitary dysfunction resulting in ongoing hypogonadism (Agha et al., 2004; Behan et al., 2008; Schneider et al., 2006; Wagner et al., 2010). At least in some cases, the pathology associated with these hypoendocrine states is attributed to primary and/or secondary injury to the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. However, major trauma is stressful to the body and results in increases in both adrenocorticotropin and cortisol (Woolf, 1992). The stress of acute or critical illness can result in hypothalamic-pituitary hypogonadism (van den Berghe et al., 2001; Woolf et al., 1985). Based on other stress paradigms, preserved or elevated cortisol levels may also contribute to hypogonadism (Kalantaridou et al., 2004; Mastuorakis and Pavlatou, 2005). Also, stress-induced elevations in estradiol have been noted in critically ill patients, including patients with major trauma and sepsis, where peripheral aromatization has been implicated with regard to these increased levels (Dossett et al., 2008 a,b; May et al., 2008; Spratt et al., 2006, 2008). In contrast, a significant portion of critically ill patients with severe TBI are also susceptible to adrenal insufficiency (AI), a phenomenon often induced by drugs commonly used in the intensive care unit (ICU) setting and often requiring additional ICU management to effectively support the patient who is in a coma (Hildreth et al., 2008; Llompart-Pou et al., 2007). The effects of cortisol on both systemic physiology and TBI pathology are not well synthesized, as experimental studies suggest that glucocorticoids can impair the ability of astrocytes to remove glutamate from the synapse. This may be one rationale for why clinical treatment with methylprednisolone in a randomized clinical trial was linked with increased adverse TBI outcome (Roberts et al., 2004). The literature on testosterone is also mixed in that in vivo work suggests that increased lesion size in stroke occurs with testosterone treatment, yet in vitro work suggests that aromatization in CNS (astrocytes) can be neuroprotective (Azcoitia et al., 2003; Garcia-Segura et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2002,2005).

Biomarkers identified in TBI often represent structural damage associated with the injury. Although not yet a part of standard clinical care, biomarkers such as S100B, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), and myelin basic protein (MBP), measured in the acute phases of injury can be informative about longer term outcomes (Berger, 2006; Berger et al., 2007; Kochanek et al., 2008; Mercie et al., 2008; Yamazaki et al., 1995). Because the literature suggests that hormones can influence damage after TBI and are associated with the stress response occurring in critical illness, we wanted to characterize temporal hormone profiles during the first week after TBI and determine if they can effectively predict outcome. Most biomarker work has focused on associations between a singular marker of interest and global outcome or survival status (Berger, 2006). Further, point estimates of biomarkers primarily have been utilized, (e.g. max, mean) and less is known about whether temporal modeling strategies such as trajectory analysis (TRAJ) (Nagin, 2005) are more informative. Other novel statistical modeling systems have emerged to more fully describe the complex relationships that exist between biomarkers in a biochemical synthesis or signaling pathway within the context of disease. Structural equations modeling (SEQM) is one method by which to represent these biological relationships within the statistical approach.

We hypothesized that sex steroids decline after injury in the setting of relatively preserved cortisol, rapid onset acute hypogonadism, and increased peripheral aromatase activity. Given the mixed literature about sex and hormones in relation to pathophysiology and outcome, the purpose of this study was to replicate previous findings regarding early hypogonadism and acute AI incidence and extend this work by 1) conducting a careful characterization of acute serum hormone profiles over time and identifying their potential sources of production; 2) assessing how sex and other demographic and clinical factors influence hormone profiles; 3) establishing hormone relationships with outcome using a biologically relevant statistical approach; and 4) evaluating hormones as informative biomarkers in TBI prognosis. We hypothesized that hormone profiles observed after TBI could serve as useful biomarkers in predicting acute and long-term outcomes.

In the setting of relatively stable cortisol levels, the data show that sex and pituitary hormones decline for the overall population. However, residual sex steroid production occurs from peripheral sources through adrenal production and peripheral aromatization (Lueprasitsakul and Longcope, 1990; Lueprasitsakul et al., 1990; Yildiz and Azziz. 2007). Group based TRAJ analysis, coupled with SEQM, effectively delineated distinct subpopulations of patients with serum hormone profiles that closely reflect physiological processes occurring with hormone production in this critically ill and injured population. Results show elevated hormone levels in some subpopulations compared to controls that appear to be reflective of greater injury severity. This approach shows that hormone profiles are effective prognosticators for acute mortality and long-term global outcome.

Methods

Study design and subjects

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pittsburgh. We evaluated 117 adults with severe TBI at our level 1 trauma center. Subjects were between the ages of 16 and 75, had a severe TBI based on a Glasgow Coma Scale ≤8 with positive findings on head computed tomography, required an extraventricular drainage catheter (EVD) for intracranial pressure (ICP) monitoring and management, and had at least two serum samples available for analysis. Patients with penetrating brain injury or with prolonged cardiac or respiratory arrest at injury were excluded from the study. Patients were also excluded if they had a previous history of pituitary or hypothalamic tumor, history of breast cancer requiring chemotherapy treatment/tamoxifen, history of prostate cancer requiring orchiectomy or LH suppression agents, or untreated thyroid disease. Additionally, 14 healthy subjects were separately enrolled as controls for serum hormone measurement. Control subjects did not have previous history of endocrine pathology and were not taking hormones for replacement therapy or contraception. Additionally, control women were interviewed about their reproductive history and menopausal status. Pre-menopausal females were sampled either in the follicular phase (days 5–10) or the luteal phase (days 18–23) of their cycle. For the healthy control population, there were n=7 men, and n=7 women enrolled. For women, n=2 were in the follicular phase, whereas n=4 were in the luteal phase of their cycle, and one menopausal woman was evaluated.

TBI subjects were admitted to the neurotrauma intensive care unit to receive treatment consistent with The Guidelines for the Management of Severe Head Injury (Bullock et al., 1996). This included initial placement of an EVD, central venous catheter, and arterial catheter. When clinically necessary, surgical intervention for decompression of mass lesions was provided. Elevated ICP was treated in a stepwise fashion to regain control and maintain the pressure within normal parameters (<20 mm Hg), and cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) was maintained at >60 mm Hg. If CPP remained low, then mean arterial pressure (MAP) was supported with pressors or inotropes to keep MAP >90 mm Hg. Temperature was monitored, and a small subset of subjects received moderate hypothermia (temperature 32.5–33.5°C for 48 h) if they were enrolled in a randomized controlled clinical trial evaluating moderate hypothermia after severe TBI. All subjects not receiving hypothermia were treated to maintain a normothermic state. In total, 11 patients received hypothermia, and 106 remained normothermic.

Serum sample collection

Blood was primarily collected at ∼7:00 a.m. daily for enrolled TBI subjects. Given the medical acuity of these subjects, they were not always present or able to have a morning sample taken for each of the first 7 days after injury. At least one sample per day was taken from 32 subjects where the sample was collected in the evening (7:00 p.m.) instead of the morning. For 21 additional subjects, an extra sample was collected on one day in the evening when patients were clinically available for the blood draw. Upon collection, each sample was centrifuged, aliquoted in polypropylene cryovials, and stored at −80°C until the time of assay. For control subjects, blood was drawn at 7:00 a.m., processed and stored for later batch analysis. Hormone levels post-TBI were measured in a total of 536 samples.

Serum hormone measurements

Serum cortisol, testosterone, progesterone, and estradiol were measured using radioimmunoassay with the Coat-A-Count® In-vitro Diagnostic Test Kit (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc., Los Angeles CA). Each kit was a solid-phase 125I radioimmunoassay designed for the direct, quantitative measurement of each hormone in serum using 25μl (cortisol and testosterone) or 100 μl (estradiol and progesterone) sample aliquots. The inter-assay and intra-assay coefficients of variation (CV) were <10 % for these assays. FSH and LH levels were measured in duplicate using a highly sensitive fluoroimmunometric assay (IFMA) (Delfia, Perkin Elmer-Wallac, Turku, Finland). This assay uses a solid phase two-site sandwich technique. The inter-assay and intra-assay CV's were <10%. Studies suggest pituitary hormone stability under a variety of collection and storage conditions (Evans et al., 2001).

Demographic and injury data

Demographic and premorbid variables including age, sex, menopausal status, body mass index (BMI), and racial background were recorded. Menopausal status was obtained by subject/family report when possible. When this information was not available, subjects >50 years of age were defined as post-menopausal.

Hypothermia status and mechanism of injury were recorded for each subject. Initial hospital GCS scores were recorded for each patient after resuscitation and without the influence of paralytics. Acute care hospital length of stay (LOS), acute care discharge location, and injury severity score (ISS) were obtained. Type of injury recorded from initial head CT report, as well as type and number of acute care complications, were collected. Acute AI status during the sampling period was coded using criteria previously published by Cohan and associates (2005), which included two consecutive morning cortisol levels of <150 ng/ml or one morning cortisol level of 50 ng/ml. Intravenous glucocorticoid and vasopressor use during the sampling period was recorded for comparison with AI status. The use of adrenal suppressing agents, including pentobarbital, etomidate, fentanyl, and propofol was also recorded and compared to AI status.

Outcomes data

Patients were administered Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) scores at 6 months post-injury. The GOS is a widely utilized measure that classifies outcome into five categories: 5=good recovery, 4=moderate disability, 3=severe disability, 2=persistent vegetative state, and 1=death (Jennett and Bond, 1975). For this study, GOS categories were collapsed into 1 vs. 2/3 vs. 4/5. Mortality during acute care hospitalization and mortality after acute care discharge was recorded by reviewing medical records and the Social Security Death Index (http://ssdi.rootsweb.ancestry.com/).

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics, including means, standard error of the mean (SEM), and medians were computed for all continuous variables. There were 117 subjects with at least two values recorded for progesterone and cortisol. 111 subjects had at least two samples for estrogen, and 115 had at least two samples for testosterone. Frequencies and percentages were determined for categorical variables. Data were checked for data errors, and normality was assessed for all continuous variables using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test. Hormone levels were graphed by day post- injury, gender, and hormone trajectory group membership. Sex, along with other independent variable differences in daily hormone values and continuous data, were compared using the Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis tests. Differences with regard to categorical data were assessed using χ2 analysis with Fisher's Exact test when appropriate.

Hormone profile assessments used a PROC TRAJ Macro (Jones et al., 2001) for SAS software (version 9.2. Copyright [2002–2008] SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). TRAJ is a specialized application of finite mixture modeling that assesses patterns of change over time (Nagin, 2005). TRAJ analysis uses maximum likelihood estimates as a way to handle missing values. The advantages of maximum likelihood estimation are well documented (Little and Rubin, 1987; Muthen et al., 1987; Wothke 2000). The TRAJ procedure determines trends in longitudinally collected data by identifying trajectory groups also on a likelihood basis. This method uses a probability function to discern a set of trajectories that closely resemble one another. TRAJ assumes the existence of unobserved (latent) subpopulations and leverages the power of repeated sampling to relate temporal patterns. Thus, TRAJ analyses can identify clusters of individuals following similar progressions of behavior or outcome over age or time. We applied this method to examine clusters of subjects following similar serum hormone profiles across time. Preliminary analyses (data not shown) were conducted with a male-only population, as well as the mixed-sex population, to determine how gender influenced TRAJ formulation and outcomes prediction. Mixed-population TRAJ results were more stable and informative, and were superior when predicting outcome.

Because daily hormone levels for the cohort were not normally distributed, hormone data for each day post-injury were ranked prior to deriving TRAJ groups for the population. The probability distribution of the data was determined using a censored normal approach, often used when there is a minimal detectable limit for data derived from hormones or other biomarker assays. We tested models ranging from one to four trajectory groups for each hormone. The number of TRAJ groups for each hormone was determined by evaluating the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), the Akaike information criterion (AIC), and by using clinical and theoretical knowledge about each hormone based on descriptive hormone analysis for the cohort. Each subject was assigned to a trajectory group based on posterior probability. Model diagnostics, such as average group posterior probability, odds of correct classification, and group membership comparisons, were used to assess model accuracy. The average posterior probability in our final models for each group and hormone ranged from 0.80 to 0.97, well above the 0.7 recommended for TRAJ (Nagin, 2005). TRAJ uses the maximum likelihood method (Fisher, 1922) to estimate the posterior probability of group membership. TRAJ groups for each hormone were labeled as high, middle, low, riser, and decliner based on their pattern of change over time.

The hormones assessed are synthesized and metabolized within the same steroidogenesis pathway, and progesterone is a synthetic precursor to the other hormones evaluated (Fig. 1a). SEQM was used to characterize hormone profiles simultaneously in relation to each other and outcome, while adjusting for other variables significantly related to outcome in bivariate analysis (Fig. 1b). Preliminary bivariate analysis (data not shown) were conducted with age and GCS using all covariates in Table 1. Results showed age and GCS as the primary covariates influencing outcome. SEQM analyses were performed using M-plus software (version 4. [Copyright 1998–2006] Muthen & Muthen, Los Angeles, CA). Preliminary analyses (data not shown) systematically compared the ability to predict outcome based on mean values across the sampling period versus TRAJ. TRAJ group membership was more informative with outcome prediction. Both direct and indirect (mediating) effects were assessed for progesterone. Because many of our variables in the SEQM model were categorical (e.g. trajectory groups, GOS), we used the nonparametric bias-corrected bootstrap method to estimate both direct and mediating effects (Efron, 1987). The bootstrap method utilizes random sampling with replacement from the original cohort so that a new cohort of the original size is obtained (the first bootstrap sample). A minimum of 1,000 samples typically are required to compute confidence limits (Efron and Tibshirani, 1993); our computations used 5,000 bootstrap samples. The bias-corrected bootstrap method was used for mediation analysis because of its rigorous approach in computing confidence intervals for mediated effects within the model (MacKinnon et al., 2004). Sensitivity analyses were conducted for the models, where 30% of the data was randomly eliminated and the model repeatedly refitted to establish SEQM consistency.

FIG. 1.

(A) Schematic of peripheral steroidogenesis highlighting progesterone, cortisol, estradiol, and testosterone. The adrenal gland can produce each of these hormones, and peripheral conversion of testosterone to estradiol can occur in cell types including adipocytes, osteoblasts, and fibroblasts. (B) Theoretical multivariate model for SEQM modeling that incorporates biologically relevant relationships between hormones for prediction of outcome. Theoretical hormone prognostic model: direct effects from hormones and demographic variables on outcome are represented by arrows. Indirect (mediated) effects from progesterone on outcome through other hormones are represented by *. SEQM, structural equations modeling.

Table 1.

Description of the TBI Population by Gender and Age

| Women (n=28) | Men (n=89) | p-value | Age (Years) | p-value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiological Injury Type | |||||||||||

| Subdural Hematoma, % | 43 | 51 | p=0.108 | 38.5±1.9 (32.6±1.7) | p=0.02 | ||||||

| Diffuse Axonal Injury, % | 32 | 28 | p=0.698 | 28.9±1.7 (39.9±1.7) | p<0.001 | ||||||

| Epidural Hematoma, % | 11 | 12 | p=0.949 | 32.8±3.2 (36.4±1.5) | p=0.34 | ||||||

| Subarachnoid Hemorrhage, % | 71 | 66 | p=0.335 | 37.8±1.6 (31.3±2.4) | p=0.03 | ||||||

| Contusion, % | 64 | 42 | p=0.084 | 38.1±1.9 (34.0±1.9) | p=0.13 | ||||||

| Intraventricular Hemorrhage, % | 21 | 34 | p=0.488 | 35.0±2.7 (36.3±1.5) | p=0.67 | ||||||

| Intracerebral Hemorrhage, % | 39 | 30 | p=0.875 | 40.2±2.4 (33.7±1.5) | p=0.02 | ||||||

| Acute Care Mortality | |||||||||||

| %Dead | 36 | 25 | p=0.331 | 44.1±2.5 | p<0.001 | ||||||

| %Alive | 64 | 75 | 33.2±1.5 | ||||||||

| GCS, Median(IQR) | 6 (5,7) | 6 (4,7) | p=0.224 | r=0.17 | p=0.06 | ||||||

| ISS, Median (IQR) | 34 (28,48) | 33 (29,38) | p=0.534 | r=−0.20 | p=0.03 | ||||||

| Menopausal Status | |||||||||||

| %Post-Menopausal | 25 | NA | NA | – | – | ||||||

| %Pre-Menopausal | 75 | NA | |||||||||

| BMI, Mean (SE) | 27.0 (1.6) | 26.8 (0.5) | p=0.328 | r=0.067 | p=0.471 | ||||||

| Age, years, Mean(SE) | 39 (3) | 35 (2) | p=0.298 | – | – | ||||||

| %<40 | 50 | 64 | p=1.85 | – | – | ||||||

| %>40 | 50 | 36 | – | – | |||||||

| Length of Hospital Stay, days, Mean(SE) | 18 (2) | 22 (1) | p=0.211 | R=− 0.23 | p=0.01 | ||||||

| Mechanism of Injury | |||||||||||

| Automobile/Motorcycle, % | 54 | 62 | p=0.674 | 32.7±1.5 | p=0.001 | ||||||

| Fall/Jump, % | 25 | 18 | 45.4±3.5 | ||||||||

| Other, % | 21 | 20 | 37.5±2.8 | ||||||||

| Discharge Disposition | |||||||||||

| Acute Rehabilitation, % | 46 | 52 | p=0.837 | 33.0±1.7 | p=0.003 | ||||||

| Death, % | 36 | 25 | 44.1±2.5 | ||||||||

| Nursing Home, % | 11 | 13 | 31.7±3.1 | ||||||||

| Other, % | 7 | 10 | 36.4±6.0 | ||||||||

| Complications, % present | |||||||||||

| Pulmonary | 61 | 71 | p=0.285 | 34.7±1.6 (38.7±2.3) | p=0.17 | ||||||

| Infectious Diseases | 14 | 17 | p=0.728 | 30.4±2.2 (37.0±1.5) | p=0.02 | ||||||

| Cardiac | 14 | 6 | p=0.216 | 39.9±5.4 (35.6±1.4) | p=0.39 | ||||||

| Musculoskeletal | 4 | 2 | p=0.567 | 30.0±11.5 (36.1±1.4) | p=0.48 | ||||||

| Hematological | 11 | 12 | p=0.798 | 35.1±3.8 (36.0±1.4) | p=0.82 | ||||||

| Renal | 39 | 8 | p<0.001 | 39.9±3.3 (35.2±1.5) | p=0.20 | ||||||

| Wounds/Integument | 11 | 9 | p=0.801 | 41.4±3.7 (35.3±1.4) | p=0.19 | ||||||

| Gastrointestinal | 4 | 11 | p=0.292 | 38.8±5.3 (35.6±1.4) | p=0.49 | ||||||

| Neuro/Endocrine | 25 | 20 | p=0.61 | 35.0±2.6 (36.2±1.6) | p=0.71 | ||||||

| Other | 7 | 5 | p=0.630 | 41.3±5.1 (35.6±1.4) | p=0.35 | ||||||

| Hypothermia, %Yes | 18 | 7 | p=0.130 | 26.4±2.2 (37.2±1.5) | p=0.001 | ||||||

| Number of Complications | 2.21±0.3 | 1.92±0.2 | p=0.354 | r=− 0.06 | p=0.54 | ||||||

| Acute Adrenal Insufficiency Status, %Yes | 32 | 45 | p=0.177 | 31.1±1.8 (40.0±2.0) | p=0.002 | ||||||

| Glasgow Outcome Score 6 months, % | 1 | 2/3 | 4/5 | 1 | 2/3 | 4/5 | p=0.309 | 1 | 2/3 | 4/5 | p<0.001 |

| 37 | 41 | 22 | 32 | 37 | 32 | 45.6±2.4 | 31.3±2.1 | 33.3±2.2 | |||

IQR, interquartile range; Parenthetical age (age), age for group without the characteristic or variable described.

Results

Description of the cohort

The mean age of the cohort was 36.2±1.4 years. Women represented 24% of the population, and 25% of these subjects were categorized as menopausal. Also, 34% of the male population was >40 years of age. The primary mechanism of injury was motor vehicle collisions (42%) followed by falls (20%). The median GCS for the main cohort was 6, and the mean ISS score was 34.4±1.0. This population had an average of 2.0±0.2 complications and a 27% acute care mortality rate. The mean hospital LOS was 20.9±1.1 days. Half of the population was discharged to an acute rehabilitation facility, and 19% were discharged to a skilled nursing or long-term acute care facility. Of this cohort, 41.9% developed AI based on criteria outlined by Cohan and associates (2005). The average BMI was 26.9±0.6. Table 1 outlines population characteristics by sex and age. There were no gender differences in types of injury observed by head CT, although women tended to have more cerebral contusions than men (p=0.08). Women did have a higher renal complication rate than men (p<0.001). Subjects who died acutely from their injuries were significantly older than those who survived (p<0.001), despite having better admission GCS and ISS scores. Subjects classified with AI were significantly younger than patients without AI (p=0.002). Of the 117 subjects, 21 had both a morning and evening sample collected on one day at some point during the sample collection period. For these subjects, values were averaged after comparing morning and evening hormone levels. There were no significant differences between morning and evening levels: cortisol (243.8±24.79 vs. 234.95±28.8 ng/ml), testosterone (7.0±1.4 vs. 6.1±1.2 nmol/L), progesterone (2.6±0.5 vs. 4.5±1.0 ng/ml), and estradiol (75.3±11.8 vs. 70.7±11.2 pg/ml).

Serum hormone levels by day and gender after TBI

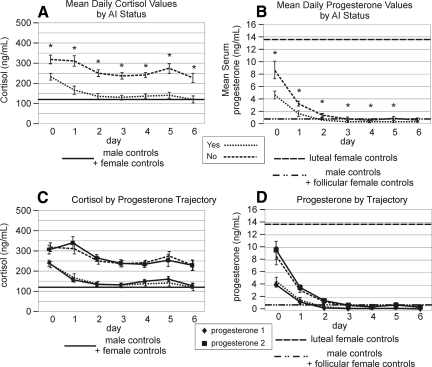

Figure 2 summarizes serum hormone levels by day and by sex for cortisol, progesterone, testosterone, and estradiol compared to healthy controls (Table 2). Mean day 0 cortisol levels (Fig. 2a) were higher than control values for both men and women (both p<0.001). Serum cortisol levels decreased by day 6 for both men and women after TBI, and values were not significantly different than those for controls. For progesterone (Fig. 2b), day 0 levels for women with TBI were at levels between that observed for healthy premenopausal control subjects in the luteal vs. follicular phase of their cycle. In contrast, day 0 progesterone levels for men with TBI were higher than for their healthy controls (p<0.001). Serum progesterone levels declined dramatically over time for both men and women such that by day 6 post-TBI, levels were similar to control values for men, women in follicular phase, and post-menopausal women.

FIG. 2.

Daily hormone levels by sex over the first 6 days after severe TBI compared to those of healthy controls. (A) Mean serum cortisol levels. There were no significant sex differences in cortisol levels over the time course. (B) Mean serum progesterone levels. There were no significant sex differences levels over the time course. (C) Mean serum testosterone levels. Female TBI subjects had testosterone levels higher than controls, and male values were higher than female values for days 0–2 (p<0.001 all comparisons). (D) Mean serum estradiol levels. Estradiol values for men were elevated compared to controls on days 0–2, and estradiol levels for women were significantly higher than for men only on day 0 (p<0.024 all comparisons). (E) Mean serum FSH levels. Values were significantly higher for women compared to those for men on days 0–5 (p<0.004 all comparisons). (F) Mean serum LH levels. Values were significantly higher for women compared to men on days 0–1 and 4 (p<0.001 all comparisons).

Table 2.

Serum Hormone Values for Healthy Control Population (n=14 Subjects)

| Control values | |

|---|---|

| Cortisol | 131.5±12.2ng/mL |

| Progesterone | |

| Men | 0.8±0.1ng/mL |

| Post-menopausal | 0.57ng/mL |

| Follicular Phase | 0.76±0.2ng/mL |

| Luteal Phase | 13.9±4.6ng/mL |

| Pre-menopausal | 9.5±4.0ng/mL |

| Testosterone | |

| Men | 15.9±3.0nmol/L |

| Women | 0.7±0.1nmol/L |

| Estradiol | |

| Men | 37.3±5.6pg/mL |

| Post-menopausal | 29.6pg/mL |

| Follicular Phase | 63.9±9.1pg/mL |

| Luteal Phase | 105.8±17.1pg/mL |

| LH | |

| Men | 4.6±0.9IU/L |

| Post-menopausal | 26.2IU/L |

| Pre-menopausal | 4.9±1.2IU/L |

| FSH | |

| Men | 5.07±1.5IU/L |

| Post-menopausal | 51.6IU/L |

| Pre-menopausal | 4.0±0.4IU/L |

Mean day 0 testosterone levels for men with TBI (Fig. 2c) were lower than those for their controls (p=0.002). In contrast, testosterone levels in women with TBI were higher than those for their controls (p<0.001). Serum testosterone levels decreased daily such that by day 6, both men and women with TBI had serum testosterone levels that were similar to those of healthy female controls. Mean day 0 estradiol levels for women with TBI (Fig. 2d) were variable and somewhat elevated compared to those of healthy premenopausal women. Day 0 serum estradiol values for men with TBI were significantly higher than those of healthy control men (p=0.024). Although not as sharp of a decline as occurred with progesterone and testosterone, estradiol levels did diminish over time such that by day 6, hormone levels for both men and women after TBI were low.

In Figure 2e, there were significant sex differences for day 0 FSH values after TBI (p<0.001). Whereas day 0 FSH levels for men with TBI were similar to those for male controls, day 0 FSH levels for women with TBI were higher than those for pre-menopausal female controls (p=0.004). FSH levels fell after TBI such that by day 6 post-TBI, FSH levels were significantly lower than in healthy controls for both men (p<0.001) and women (p=0.004) after TBI. Similar sex and time trends were noted for LH (Fig. 2f). As with FSH, day 0 LH levels for men with TBI were similar to those of male controls, and day 0 LH levels for women with TBI were higher than for pre-menopausal female controls (p=0.002). LH levels declined for both groups over time, and LH levels were significantly lower than those in healthy controls for men and women by day 6 post-TBI. Although gonadotropin levels were initially high, post-menopausal women also had a decline in gonadotropin values over time (LH Day 0: 31.9±9.78 IU/L, Day 6: 3.29±0.63 IU/L; FSH Day 0: 40.79±6.63 IU/L, Day 6: 11.69±3.38 IU/L).

Serum hormone trajectory profiles and associated hormone levels after TBI

There were three distinct TRAJ group profiles identified for serum cortisol (Fig. 3a): a high, decliner, and low group. The high group had the highest cortisol levels throughout the sampling period. Levels for the low group started high and declined over time to reach control levels by day 3 post-TBI. However, the low group levels began to rise again by day 4 in the sampling period. The decliner group levels started high and continued to decline over the entire sampling period and were similar to those of controls by day 3. Cortisol levels for each TRAJ were significantly different from each other for all 7 days (p<0.001 for all comparisons) (Fig. 3b).

FIG. 3.

(A) Trajectory groups for profiles over time and percent membership for each trajectory group for serum cortisol using ranked data. The y-axis represents the relative rank. TRAJ identified three groups for cortisol: group 1=decliner group, group 2=low group, 3=high group. (B) Mean serum cortisol concentrations over time for each cortisol trajectory group compared to those of healthy controls. There were significant differences in TRAJ group cortisol levels on days 0–6 (p<0.001 all comparisons).

There were two distinct TRAJ groups identified for serum progesterone (Fig. 4a). Whereas both groups declined over time, progesterone levels in low progesterone group were significantly lower than those in the high group for all days post-TBI (p=0.005 for all comparisons) (Fig. 4b).

FIG. 4.

(A) Trajectory group profiles over time and percent membership for each TRAJ group for serum progesterone using ranked data. The y-axis represents the relative rank. TRAJ identified two groups for progesterone: 1=low group, 2=high group. (B) Mean serum progesterone concentrations over time for each progesterone trajectory group compared to those of healthy controls. There were significant differences in TRAJ group progesterone levels on days 0–6 (p<0.001 all comparisons).

For testosterone, there were three distinct TRAJ group profiles identified (Fig. 5a), including a high, decliner, and low group. For days 0–1, testosterone levels were significantly less for the low group than for the other groups (p<0.001 both comparisons). By day three, decliner group levels were similar to those in the low group, however high group levels remained significantly higher than those for the other groups for days 3–5 (p<0.001 for all comparisons) (Fig. 5b).

FIG. 5.

(A) TRAJ groups for profiles over time and percent membership for each TRAJ group for serum testosterone using ranked data. The y-axis represents the relative rank. TRAJ identified three groups for testosterone. 1=low group, 2=decliner group, 3=high group. (B) Mean serum testosterone concentrations over time for each testosterone TRAJ group compared to those of healthy controls. There were significant differences in TRAJ group testosterone levels on days 0–5 (p<0.001 all comparisons).

There were four distinct estradiol TRAJ group identified (Fig. 6a). There was a low, middle, and high group, whereas a riser group was characterized by a late rise in serum estradiol levels. In fact, the riser group had significantly higher estradiol levels than the low and middle groups on days 5–6 post-TBI (p<0.001 all comparisons). Although there was some variability in estradiol levels, the high group had significantly higher estradiol levels than the other groups from day 0–5 post-TBI (p<0.001 for all comparisons) (Fig. 6b).

FIG. 6.

(A) TRAJ groups for profiles over time and percent membership for each TRAJ group for serum estradiol using ranked data. The y-axis represents the relative rank. TRAJ identified four groups for estradiol: 1=low group, 2=riser group, 3=middle group, 4=high group. (B) Mean serum estradiol concentrations over time for each estradiol TRAJ group compared to those of healthy controls. There were significant differences in TRAJ group estradiol levels on days 0–5 (p<0.001 all comparisons).

Hormone trajectory group associations with demographic and clinical variables after TBI

Hormone TRAJ group comparisons were made with demographic variables (Table 3a), injury variables (Table 3b), and hormone TRAJ group assignment (Table 3c). Sex was only a significant factor in progesterone TRAJ group membership (p=0.028). Women made up a larger proportion of the population in the high progesterone TRAJ group than in the low TRAJ group. Older age was associated with TRAJ group memberships with the high cortisol (p=0.001), progesterone (p<0.001), and estradiol (p=0.011) TRAJ groups. Additionally, the riser estradiol TRAJ group was composed of older subjects (mean age 48±6.3 years). Higher BMI was associated with high progesterone (p=0.003), estradiol (p=0.013), and testosterone (p=0.018) TRAJ groups. Hypothermia and injury severity, characterized by both ISS and GCS scores, were not associated with any hormone TRAJ group. People having high progesterone levels were more likely to have high cortisol values (p<0.001), high estradiol values (p<0.001), and high testosterone values (p=0.039). There was no significant relationship between secondary hormones (cortisol, estradiol, testosterone) in the multivariate SEQM models.

Table 3A.

Demographic Characteristics by Hormone Trajectory Group Membership

| Hormone trajectories | Sex % women | Age mean±SE | BMI mean±SE | Post menopause % | Men age>40 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortisol | |||||

| Decliner | 23 | 32±2.3 | 26.6±1.2 | 0 | 26.1 |

| Low | 19 | 33±1.9 | 26.0±0.8 | 10 | 27.9 |

| High | 32 | 44±2.6 | 28.9±1.1 | 54.5 | 52.2 |

| Statistics | p=0.369 | p=0.001 | p=0.102 | p=0.007 | p=0.101 |

| Progesterone | |||||

| Low | 16 | 32±1.5 | 25.7±0.8 | 9.1 | 23.2 |

| High | 34 | 42±2.2 | 28.7±0.9 | 35.3 | 51.5 |

| Statistics | p=0.028 | p<0.001 | p=0.003 | p=0.099 | p=0.010 |

| Estradiol | |||||

| Low | 24 | 31±2.3 | 23.9±0.9 | 0 | 26 |

| Riser | 29 | 48±6.3 | 24.4±1.1 | 50 | 80 |

| Middle | 18 | 34±2.1 | 27.8±0.9 | 22 | 31 |

| High | 39 | 40±2.8 | 28.5±1.3 | 36 | 41 |

| Statistics | p=0.184 | p=0.011 | p=0.013 | p=0.288 | p=0.149 |

| Testosterone | |||||

| Low | 29 | 32±2.7 | 24.1±0.8 | 13 | 25 |

| Decliner | 23 | 36±1.9 | 27.8±1.0 | 15 | 36 |

| High | 17 | 40±3.0 | 27.7±0.9 | 80 | 44 |

| Statistics | p=0.566 | p=0.178 | p=0.018 | p=0.016 | p=0.440 |

Table 3B.

Injury Characteristics by Hormone Trajectory Group Membership

| |

|

|

|

|

|

6 Months GOS,% |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hormone trajectories | GCS median | ISS mean±SE | Hypothermia status % hypothermic | AI status % | Acute care mortality % dead | 1 | 2/3 | 4/5 |

| Cortisol | ||||||||

| Decliner | 6 | 34.8±1.6 | 10 | 65 | 23 | 31 | 34 | 35 |

| Low | 6 | 34.5±1.2 | 11 | 62 | 21 | 24 | 45 | 31 |

| High | 6 | 34.9±1.9 | 6 | 3 | 41 | 47 | 31 | 22 |

| Statistics | p=0.532 | p=0.916 | p=0.720 | p=0.0001 | p=0.101 | p=0.314 | ||

| Progesterone | ||||||||

| Low | 6 | 35.0±1.0 | 9 | 73 | 19 | 26 | 40 | 34 |

| High | 6 | 34.2±1.5 | 10 | 10 | 38 | 42 | 35 | 23 |

| Statistics | p=0.465 | p=0.395 | p=1.00 | p=0.0001 | p=0.026 | p=0.176 | ||

| Estradiol | ||||||||

| Low | 6 | 33.8±1.8 | 12 | 78 | 4 | 5 | 40 | 55 |

| Riser | 7 | 38.6±3.3 | 0 | 33 | 43 | 57 | 29 | 14 |

| Middle | 6 | 34.9±1.3 | 8 | 43 | 26 | 28 | 39 | 33 |

| High | 6 | 34.3±2.0 | 14 | 29 | 50.0 | 60 | 32 | 8 |

| Statistics | p=0.381 | p=0.689 | p=0.712 | p=0.002 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | ||

| Testosterone | ||||||||

| Low | 7 | 33.8±1.8 | 4 | 62 | 7 | 8 | 46 | 46 |

| Decliner | 6 | 35.7±1.3 | 11 | 36 | 33 | 39 | 41 | 20 |

| High | 6 | 33.2±1.5 | 10 | 48 | 37 | 50 | 23 | 27 |

| Statistics | p=0.187 | p=0.452 | p=0.683 | p=0.095 | p=0.011 | p=0.009 | ||

GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; ISS, injury severity score; AI, adrenal insufficiency GOS, Glasgow Outcome Scale.

Table 3C.

Hormone Trajectory Group Membership by Hormone Trajectory Group

| |

|

Cortisol,% |

Progesterone,% |

Estradiol,% |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decliner | Low | High | Low | High | Low | Riser | Middle | High | |||||

| Progesterone,% | Low | 31 | 66 | 3 | X2=53.03, p<0.001 | ||||||||

| High | 18 | 18 | 64 | ||||||||||

| Estradiol,% | Low | 28 | 64 | 8 | X2=15.62, p=0.014 | 88 | 12 | X2=19.69, p<0.001 | |||||

| Riser | 14 | 57 | 29 | 71 | 29 | ||||||||

| Middle | 31 | 43 | 26 | 57 | 43 | ||||||||

| High | 14 | 32 | 54 | 29 | 71 | ||||||||

| Testosterone,% | Low | 11 | 79 | 11 | X2=18.93, p=0.001 | 79 | 21 | X2=6.33, p=0.039 | 35 | 4 | 35 | 27 | X2=8.91, p=0.178 |

| Decliner | 35 | 35 | 30 | 53 | 47 | 13 | 9 | 54 | 24 | ||||

| High | 23 | 33 | 43 | 50 | 50 | 28 | 0 | 45 | 28 | ||||

Because age was significantly associated with hormone TRAJ group membership, we explored further by evaluating hormone TRAJ membership by menopausal status for women and age dichotomized at 40 years for men. Women in menopause represented a larger portion of the female population in the high cortisol (p=0.007) and testosterone (p=0.013) TRAJ groups. Men >40 years of age also represented a larger portion of males in the high progesterone (p=0.010) group. Acute AI status was associated with cortisol, progesterone, and estradiol TRAJ groups having lower levels (p<0.002 all comparisons).

Acute care mortality was associated with high TRAJ group membership for progesterone (p=0.026), estradiol (p=0.001), and testosterone (p=0.014). Also, subjects in the riser estradiol TRAJ were more likely to die during the acute hospitalization. High estradiol and testosterone TRAJ group membership, as well as the estradiol riser group, was also associated with poor GOS scores at 6 months post-injury (p<0.03 all comparisons). Neither serum cortisol TRAJ group nor BMI were associated with acute mortality or GOS at 6 months.

Progesterone TRAJ group membership associations with serum hormone profiles after TBI

Progesterone is a precursor to cortisol and the gonadal hormones studied, and progesterone levels are largely regulated by the pituitary function. As such, we graphed daily levels for each hormone by progesterone TRAJ group assignment in order to evaluate pituitary hormone influences on progesterone TRAJ group and progesterone group TRAJ influences on the other gonadal and stress hormones. Serum cortisol and progesterone levels were graphed by progesterone TRAJ (Fig. 7a and b). Despite an overall decrease in serum progesterone levels over time, cortisol levels were stable in each progesterone TRAJ group. Cortisol levels remain significantly different by progesterone TRAJ group throughout the sampling period (p<0.025 all comparisons). In contrast, there were no differences in testosterone levels over time by progesterone TRAJ, and estradiol levels differed over time by progesterone TRAJ only on a few days (Fig. 7c and d) (p<0.018 days 3–5). Figure 7e and f, show FSH and LH hormone profiles over time by progesterone TRAJ group. At early times after TBI, FSH and LH levels were differentiated by progesterone TRAJ group membership (p<0.039 days 0–3 FSH; p<0.002 days 0–1 LH). The decreased ability of progesterone TRAJ to reflect differences in LH after day 1 indicates a diminishing role for the pituitary on progesterone levels at later times post-TBI.

FIG. 7.

Daily serum hormone levels by progesterone TRAJ and compared to those of healthy controls. (B) Serum progesterone levels. Hormone levels for each TRAJ group were significantly different from each other on days 0–6 post-TBI (p<0.001 all comparisons. (A) Serum cortisol levels. Hormone levels for each TRAJ group were significantly different from each other on days 0–6 post-TBI (p<0.025 all comparisons. (C) Serum testosterone levels. Hormone levels for each TRAJ group were not significantly different from each other on any day. (D) Serum estradiol levels. Hormone levels for each TRAJ group were significantly different from each other on days 3–4 post-TBI (p<0.018 both comparisons). (E) Serum FSH levels. Hormone levels for each TRAJ group were significantly different from each other on days 0–3 post-TBI (p<0.039 all comparisons). (F) Serum LH levels. Hormone levels for each TRAJ group were significantly different from each other on days 0–1 post-TBI (p<0.002 both comparisons).

Associations with AI status

To further assess hormonal relationships with AI status, we graphed daily progesterone and cortisol levels over time by AI group. Progesterone levels were significantly lower on days 0–5 (p<0.004 all comparisons), and cortisol levels were significantly lower on days 0–6 (p<0.002 for all comparisons) for subjects with AI (Fig. 8a and b). Progesterone and cortisol serum hormone levels over time by AI status were strikingly similar to both progesterone and cortisol levels by progesterone TRAJ group (Fig. 8c and d), suggesting that although overall progesterone levels decrease over time, the residual levels observed after TBI primarily influence cortisol production and AI status after TBI. In fact, 73% of people in the low progesterone TRAJ group had AI, whereas 90% of people in the high progesterone group had no AI (p<0.001) (Table 3b). AI status was not associated with vasopressor use, the use of adrenal suppressing agents, glucocorticoid use, acute mortality, or GOS 6 scores (Table 4). Glucocorticoids were given to 20.7% of the subjects in the decliner, 16.3% of subjects in the low, and 25% of subjects in the high cortisol TRAJ groups, and mean cortisol levels for those with AI and receiving glucocorticoids did not differ compared to those with AI and not receiving glucocorticoids (147.6±21.6 ng/ml AI+glucocorticoid vs. 151.3±5.1 ng/ml AI −glucocorticoids; p=0.871 ).

FIG. 8.

Daily serum profiles compared to those of healthy controls. (B) Progesterone levels by AI status. Subjects with AI have significantly lower progesterone levels for days 0–6 (p<0.001 all comparisons). (A) Cortisol levels by AI status. Subjects with AI had significantly lower cortisol levels for days 0–6 (p<0.001 all comparisons). (C) Progesterone levels by AI status with progesterone levels by progesterone TRAJ superimposed to demonstrate similarity of progesterone profiles over time. (D) Cortisol levels by AI status with cortisol levels by progesterone TRAJ superimposed to demonstrate similarity of cortisol profiles over time. AI, adrenal insufficiency.

Table 4.

Drug and Outcome Characterization Associated with Adrenal Insufficiency Status

| |

|

|

Adrenal suppressing agents |

GOS,% |

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pressors first week | Glucocorticoids first week | Etomidate | Fentanyl | Propofol | Pentobarbital | 1 | 2/3 | 4/5 | Mortality, % | |

| With AI,% | 65.3 | 19.3 | 59.2 | 100 | 100 | 16.3 | 27 | 37 | 35 | 25 |

| Without AI,% | 75.4 | 21.7 | 68.9 | 100 | 100 | 6.6 | 25 | 29 | 37 | 35 |

| p-value | p=0.293 | p=0.760 | p=0.321 | - | - | p=0.129 | p=0.46 | p=0.23 | ||

AI, adrenal insufficiency GOS,Glasgow Outcome Scale.

Serum hormone TRAJ in outcome prognostication after TBI:

We used SEQM to assess hormone influences on global outcome and survival while evaluating biologically relevant relationships between hormone levels in multivariate analysis. We included demographic and injury variables (age and GCS score) in which there were significant bivariate associations between these variables and outcome.

Figure 9 shows that both older age and lower GCS score were significantly associated with increased mortality rates. The SEQM model also shows that high progesterone TRAJ group membership was significantly associated with high cortisol, estradiol, and testosterone TRAJ group membership (p<0.021 all comparisons). High estradiol and testosterone TRAJ group membership was associated with higher mortality rates (p=0.026 and p=0.033, respectively). Tests for mediating effects show that there was a significant effect of progesterone TRAJ groups on mortality through their association with estradiol group membership (p=0.049). Figure 10 shows that older age and lower GCS also were associated with lower GOS scores at 6 months post-TBI. High progesterone TRAJ group membership was associated with high cortisol, testasterone, and estradiol TRAJ group membership (p<0.001 all comparisons), and high estradiol TRAJ membership was associated with worse outcomes. Also, estradiol TRAJ group membership mediated progesterone TRAJ associations with GOS scores (p=0.045). Serum cortisol TRAJ was not associated with mortality or GOS-6 score.

FIG. 9.

SEQM with acute mortality as outcome. Standardized coefficients are shown for direct comparison of hormonal effects on outcome. Mediated effects of progesterone and their 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals are shown in the table. Significant direct effects on outcome: age (p=0.003), GCS (p=0.002), estradiol (p=0.026), and testosterone (p=0.033). Progesterone has significant direct effect on estradiol (p<0.001) and cortisol (p<0.001), and a trend on testosterone (p=0.072). *Progesterone also has a significant indirect (mediated) effect on outcome through estradiol (p=0.049). SEQM. structural equations modeling.

FIG. 10.

SEQM with GOS at 6 month as outcome. Standardized coefficients are shown for direct comparison of hormonal effects on outcome. Mediated effects of progesterone and their 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals are shown in the table. Significant direct effects on outcome: age (p=0.002), GCS (p=0.001), and estradiol (p=0.021). Testosterone trends toward significance (p=0.163). Progesterone has significant direct effect on estradiol (p<0.001) and cortisol (p<0.001), and a trend on testosterone (p=0.072). *Progesterone also has significant indirect (mediated) effect on outcome via estradiol (p=0.045). SEQM: structural equations modeling; GOS: Glasgow Outcome Scale.

Discussion

The experimental literature demonstrates that female sex steroids can confer neuroprotection through multiple mechanisms. Clinically, however, significant injury can lead to acute hypogonadism and an acute hormonal stress response, calling into question the neuroprotection hypothesis for endogenous sex steroids after TBI. Disruption of the hypothalamus and pituitary can occur with severe TBI, and critical illness and associated clinical management practices can influence the adrenal response to injury, hypothalamic-pituitary function, and peripheral aromatization. The results of this study replicate and further extend previous work by demonstrating that hormone profiles for what are classically considered sex steroids rapidly decline over approximately the same time course as the pituitary hormones LH and FSH and primarily represent the uniform development of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in our population with severe TBI. Importantly, our data delineate TBI subpopulations with unique hormone profiles as risk factors for poor outcome and for other clinically relevant conditions such as AI. Moreover, there are specific patient subgroups with elevated estradiol who are at highest risk for poor outcome, and this finding represents a paradigm shift in thinking about how estradiol is neuroprotective in clinical populations with TBI. Finally, novel data modeling approaches such as group-based TRAJ and SEQM are effective methods for modeling TBI pathology and prognosis.

The data show that gonadal production is normally the largest contributor to overall progesterone levels and that declining progesterone levels correspond tightly with falling pituitary levels (Fig. 7). Declining pituitary hormone, estradiol, and testosterone levels are consistent with other recently published work in TBI (Wagner et al., 2010). Both studies report time-dependent decreases for FSH and LH, indicating that pituitary insufficiency significantly influences a decline in testosterone and estrogen over time. Our analyses extend beyond the concept of generalized hypogonadotropic hypogonadism to shed light on the role of extragonadal sources in residual sex steroid levels as well as the role of cortisol in sex steroid production and in predicting outcome after TBI.

On the day of injury (day 0), serum progesterone levels are elevated in men, which is consistent with previous studies assessing early serum progesterone levels prior to acute intervention with progesterone treatment (Wright et al., 2007). Other temporal hormone profiles, specifically estradiol for men and testosterone for women, are elevated compared to controls. The primary source of extragonadal steroidogenesis for these elevated levels is the adrenal gland and/or peripheral aromatization. Although corticotrophin levels were not measured, cortisol levels remained relatively constant over time for most subjects, suggesting that cortisol may be a contributing factor to hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction outside of the influence that the TBI itself may have in decreasing pituitary hormone levels over time (Van den Berghe et al., 2001). The similarities in morning versus evening cortisol data suggest disruptions in diurnal rhythms. This finding is consistent with other recent data demonstrating data suggesting that diurnal cortisol variation is disrupted after both TBI (Llompart-Pou et al., 2010) and critical illness (Paul and Lemmer, 2007).

The rapidly declining serum progesterone levels for both men and women provide a rationale for why both gender groups may benefit from acute progesterone therapy after severe TBI (Wright et al., 2007; Xiao et al., 2008). However, pharmacotherapy with progesterone results in significant elevations in progesterone that are higher than circulating levels (>300 ng/ml) (Wright et al., 2005), making it necessary to reassess hormone relationships to each other, to secondary injury, and to outcome within this treatment paradigm. Conversely, elevated estradiol profiles and their associations with poor outcome after TBI suggest that acute treatment with natural or conjugated estradiol preparations may not necessarily lead to neuroprotection as previously experimental studies have hypothesized.

Our work shows that these hormones can be grouped using TRAJ profiles over time to represent group differences in the extragonadal hormone production after severe TBI. Moreover, these hormone profiles can be analyzed in a biologically relevant way to create informative multivariate models for predicting acute mortality and global outcome. Descriptive variable comparisons to hormone TRAJ groups demonstrate that traditional demographic and injury severity variables do not fully capture information represented by the hormone TRAJ profiles. For example, the TRAJ groups generated were not age, sex, or GCS group exclusive.

Differences in daily hormone levels for men versus women were often small and non-significant, and our preliminary analysis (see Methods, data not shown) during TRAJ group formulation showed that TRAJ groups were more robust and able to predict outcome when both men and women were included in the same analysis. Decreased gonadotropins, along with the lack of large sex differences with hormone profiles, provide solid evidence that the residual hormone levels represented in these profiles over time were generated from the adrenal gland and/or peripheral aromatization. In fact, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and elevated peripheral aromatization, regardless of sex, have been noted in other studies involving critical illness, trauma, sepsis, and major surgery (Dossett et al., 2008 a,b; May et al., 2008; Spratt et al., 2006, 2008; Van den Berghe et al., 2001). Although normal FSH and LH levels for menopausal women are quite high, gonadotropin levels for our menopausal women decreased over time. Also, FSH and LH levels for women and men were similar by day 6 post-TBI. Both findings are consistent with other data involving patients with critical illness and TBI (Woolf et al., 1985).

Age was a significant contributor to TRAJ group membership, with a larger percentage of older subjects included in TRAJ groups having higher hormone levels. This result suggests that the stress response for older patients with severe TBI is greater than for their younger counterparts. The occurrence of elevated serum cortisol and estradiol levels after trauma and critical illness with advanced age after have also been documented previously (Beale et al., 2002; Desai et al., 1989; Horan, 1994; May et al., 2008). Additionally, peripheral aromatization in response to stress can increase with age (Simpson et al., 1989). Despite the strong influence of age on hormone TRAJ membership, age was still a significant independent factor in multivariate analysis in predicting outcome. As such, other age-related influences on secondary injury, complications, and co-morbid conditions probably contribute to this finding. BMI was significantly associated with TRAJ group membership for progesterone, estradiol, and testosterone. This may represent the fact that peripheral aromatase activity increases with increased adiposity (Simpson et al., 1989), and suggests that BMI may have some potential to serve as a biomarker in TBI. Injury severity levels, using both ISS and GCS scores, showed that subcategories for the severity of the neurological and concomitant injury in this severely injured population did not further influence the hormone response observed. However, the degree of neurological injury based on GCS did have an independent influence on survival and global outcome.

When evaluating the entire cohort with severe TBI, serum cortisol levels remained above that observed in the control population for much of the sampling period, and cortisol TRAJ analysis (Fig. 3) showed distinct temporal profiles. Cortisol levels by progesterone TRAJ demonstrate that despite declining progesterone levels over time, there was adequate progesterone substrate in the adrenal gland to support ongoing cortisol synthesis, and although not measured, imply relatively intact corticotrophin production. An augmented cortisol response can be a healthy response to acute stress and illness, and a diminished response did lead to the development of AI in a portion of our population, a phenomenon that can adversely impact on outcome (Behan et al., 2008; Cohan et al., 2005). Cortisol TRAJ and AI status, however, did not influence outcome in our cohort. Also, the use of various classes of drugs associated with cortisol levels and AI status did not appear to be a significant factor in this analysis. However, additional work is required to further assess factors affecting AI and outcomes.

Progesterone TRAJ did discern two distinct cortisol groups that very closely resembled the two cortisol groups identified using previously published AI criteria (Fig. 8). AI subjects had mean cortisol levels near healthy control levels, which is also consistent with the literature, (Cohan et al., 2005; Savaridas et al., 2004) and AI status was highly associated with TRAJ group membership across each of the four hormones studied. In each case, AI was associated with TRAJ groups having lower temporal hormone profiles. This finding, along with elevated testosterone for women and elevated estradiol for men, supports the concept that the adrenal gland contributes to the production of these other sex steroids.

In contrast to sustained, adrenal substrate-dependent cortisol profiles that characterize each progesterone TRAJ, testosterone and estradiol levels were less associated with progesterone TRAJ group membership. Peripheral aromatization of testosterone to estradiol is a large contributor to estradiol levels for both men and women (Lueprasitsakul and Longcope, 1990; Lueprasitsakul et al., 1990). The contribution of peripheral aromatization to both testosterone and estradiol levels in our cohort is our primary conclusion for why these hormones are not well differentiated based on progesterone TRAJ group assignment. When taking AI associations with estradiol and testosterone TRAJ together with increased testosterone levels for women and increased estradiol levels for men, these findings further support the idea that estradiol and testosterone profiles are a product of both adrenal progesterone reserves and peripheral aromatization. Gonadal production may still play a transient role in hormone profiles early when pituitary hormone levels are higher. Also, some studies show increased ovarian androgen production in menopausal women (Burger et al., 2002).

Aside from reflecting an acute stress response, other potential mechanisms underlying associations between elevated serum estradiol, testosterone, and poor outcome will require further study. This should also include cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) hormone measurements and a comparative analysis of how hormone concentrations in this compartment relate to TBI pathophysiology and are able to be used as biomarkers discriminating outcomes. Because gonadal hormones do influence several mechanisms of secondary injury in experimental models, future work might also focus on linking hormone profiles to structural injury markers linked to known secondary injury cascades. Importantly, peripheral aromatase activation can be specifically stimulated by key markers of inflammation that are also implicated as a part of the biochemical cascades that unfold after TBI such as TNF-α and other cytokines (Simpson et al., 1981). How this interplay between hormones and inflammation affects TBI and recovery is not known.

At first glance, associations between relative increases in estradiol and poor outcome appear to contrast with the experimental literature suggesting that estrogen is neuroprotective (Hurn et al., 2000; Mendelowitsch et al., 2001; Roof and Hall, 2000 a, b; Stein, 2001). However, these data cannot differentiate whether peripheral estrogen production directly influences TBI pathophysiology and/or if estrogen levels are an epiphenomenon reflecting the overall magnitude of injury and the body's stress response to this injury. The resulting direct and indirect hormonal interrelationships to TBI pathology are probably complex. For example, if peripheral aromatase activation in adipose tissue is modulated by inflammatory factors such as TNF-α (Simpson et al., 1981), an increasing peripheral inflammatory response may exacerbate TBI pathophysiology (Csuka et al., 1999; Morganti-Kossman et al., 1997) while estrogen production concomitantly increases as a byproduct. Conversely, both gonadal and thyroid hormones decline acutely in the setting of TBI (Klose, 2007), and imaging studies in uninjured subjects show that decreases in systemic thyroid and estrogen levels diminish the brain's metabolic demand (Constant et al., 2001; Silverman et al., 2010). Therefore, for some, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) activation from the critical illness and/or the TBI, and the resulting decreases in thyroid and gonadal hormone levels, may well be indirectly an adaptive response.

Further studies in experimental TBI assessing endogenous hormone profiles over time in relation to TBI pathology may also be informative, as some of the current experimental literature simply speculates that endogenous hormones are neuroprotective with regard to their observed histological and neurobehavioral endpoints. However, most experimental TBI models use an isolated brain injury model, which may not trigger the same types of systemic response that would be observed if these models also included peripheral concomitant injury (Dennis et al., 2009). Importantly, peripheral aromatase induction after stress is limited to primates, and therefore, may limit the translatability of hormone profiles to concepts such as neuroprotection and outcome with any rodent model used (Dossett et al., 2008 a,b; May et al., 2008). In comparison to other clinical studies (Berry et al., 2009; Farin and Marshall, 2004), the data suggest that age, rather than sex, is the more informative demographic variable in predicting outcome. Both older women and men have worse outcomes that are linked to age-related differences in hormone profiles.

From a statistical perspective, this study highlights the relevance of group-based TRAJ and SEQM as effective tools in discerning how these biomarkers relate to pathology and prognosis. Progesterone levels severely decline for both men and women over time. However, in univariate analysis, the progesterone TRAJ group having higher endogenous hormone levels was associated with worse outcomes. As progesterone is the synthetic precursor for estradiol, testosterone, and cortisol, SEQM was a biologically relevant way to determine the mediating effects of other hormones, particularly estradiol, on the relationship between progesterone and outcome. Further, this approach allowed us to incorporate additional variables, such as age and injury severity, that influence outcome outside of their associations with TRAJ group membership. Preliminary SEQM models were developed to comparatively assess the predictive value of point estimates (e.g., mean estradiol) and hormone TRAJ (data not shown). TRAJ group assignments were better predictors of outcome because temporal profiles yield unique information about evolving pathology over time. As an example, subjects in the decliner testosterone TRAJ group have somewhat intermediate GOS-6 scores and mortality rate compared to subjects in the low or high TRAJ group.

These results demonstrate the robustness of serum hormones as predictive markers of global outcome and the benefits of utilizing novel tools such as TRAJ and SEQM for biomarker modeling. Estradiol levels at 48 h post-admission for critical illness is an effective biomarker for predicting mortality for major trauma/surgery patients (Dossett et al., 2008 a,b; May et al., 2008). Further work will be required to determine the generalizeability of our models to other prospective TBI populations and to determine how serum hormone markers may be useful for predicting outcome in other domains such as cognition and quality of life. As our longitudinal profiles were built on 7 days of serum hormone data, there may be value in using approaches such as dynamic pattern recognition to generate prognostic information earlier during the hospital course (Singh, 1997). Also, understanding how robust serum estradiol TRAJ is as a biomarker when compared to other TBI-specific serum biomarkers published (Berger, 2006) will be an important next step.

Persistent hypopituitarism is an important clinical phenomenon affecting a large portion of the population with significant TBI (Blair, 2010; Gasco et al., 2010). Further, hypopituitarism has been associated with depression and decreased cognitive function in some small studies as well as with growth hormone dysfunction (Bavisetty et al., 2008). Future work will be required to determine if the acute hormone stress response is linked at all to a propensity for prolonged hypogonadism, and their relationships to cognition and quality of life.

Whereas the data presented here are unique and shed new light on acute hormonal response to TBI, some caveats should be considered. Although our time course and inclusion of pituitary hormones adds to the robustness of the data set, we only measured total hormone levels for each of the hormones evaluated in this study. Some literature suggests that the biologically active free fraction of cortisol and cortisol-binding globulin concentrations change in response to acquired brain injury without notable deviations outside of the reference range for total hormone levels (Savaridas et al., 2004). Other sex hormone binding globulins and their response to injury should be explored (Guennoun et al., 2008; Sutton-Tyrrell et al., 2005; Torpy and Ho, 2007). We used previously published criteria for establishing AI, and cortisol levels for our AI group were consistent with the literature (Cohan et al., 2005). However, our study design did not incorporate adrenal stimulation testing or corticotrophin levels to further define subjects as having AI (Llompart-Pou et al., 2007, 2008). Our measurements were made daily, and more frequent time intervals from which to assess hormone dynamics over time should also be considered.

Conclusions

The results of this work indicate that acute serum hormone profiles are affected by both the TBI and critical illness and are largely a reflection of the human stress response to severe TBI. The findings demonstrate the effectiveness of novel data modeling approaches such as TRAJ and SEQM in biomarkers research. The findings also challenge the concept of endogenous hormone mediated neuroprotection for women clinically after TBI, and suggest that peripheral production of sex steroids through adrenal production and peripheral aromatization dominate the acute residual serum hormone profiles observed after TBI. In addition to TBI, cortisol levels also may contribute to pituitary insufficiency during the acute illness period. Low progesterone profiles after TBI suggest that both men and women may benefit from pharmacological dosing of this hormone in clinical trial. However, careful hormone and biomarker monitoring would aid in understanding how treatment with progesterone may affect other hormone production in the adrenal and peripherally. The findings suggest that careful consideration should be given as to whether or not treatments such as estrogen supplementation may worsen outcome if given early after TBI. Additionally, consideration of acute aromatase inhibitor therapies for improving outcome in TBI subpopulations with elevated estradiol may be justified if future work implicates estrogen as causal in mediating CNS damage after TBI. Further work is required to understand the role of these hormones in the CNS early after injury and how both acute and chronic hormone profiles relate to the development of chronic hypopituitarism and support long-term neuroplasticity and recovery in the population with TBI.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Mary Synnott for figure construction, and the UPMC Trauma Registry team and the Brain Trauma Research Center for their role in data collection. This work was supported by CDC grant # R49/CCR323155 (A.K.W., S.L. B., A.F.), DODW81XWH-071-0701, DOD PT073914 (A.K.W., A.F.), and NIH 5P01NS030318-16 to (C.E.D.).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Agha A. Rogers B. Sherlock M. O'Kelly P. Tormey W. Phillips J. Thompson C.J. Anterior pituitary dysfunction in survivors of traumatic brain injury. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004;89:4929–4936. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azcoitia I. Sierra A. Veiga S. Garcia–Segura L.M. Aromatase expression by reactive astroglia is neuroprotective. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2003;1007:298–305. doi: 10.1196/annals.1286.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavisetty S. McArthur D.L. Dusick J.R. Wang C. Cohan P. Boscardin W.J. Swerdloff R. Levin H. Chang D.J. Muizelaar J.P. Kelly D.F. Chronic hypopituitarism after traumatic brain injury: risk assessment and relationship to outcome. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:1080–1093. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000325870.60129.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beale E. Zhu J. Belzberg H. Changes in serum cortisol with age in critically ill patients. Gerontology. 2002;48:84–92. doi: 10.1159/000048932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behan L.A. Phillips J. Thompson C.J. Agha A. Neuroendocrine disorders after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 2008;79:753–759. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.132837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger R.P. The use of serum biomarkers to predict outcome after traumatic brain injury in adults and children. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21:315–333. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200607000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger R.P. Beers S.R. Richichi R. Wiesman D. Adelson P.D. Serum biomarker concentrations and outcome after pediatric traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2007;24:1793–1801. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry C. Ley E.J. Tillou A. Cryer G. Margulies D.R. Salim A. The effect of gender on patients with moderate to severe head injuries. J. Trauma. 2009;67:950–953. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181ba3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair J.C. Prevalence, natural history and consequences of posttraumatic hypopituitarism: a case for endocrine surveillance. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2010;24:10–17. doi: 10.3109/02688690903536637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock R. Chesnut R.M. Clifton G. Ghajar J. Marion D.W. Narayan R.K. Newell D.W. Pitts L.H. Rosner M.J. Wilberger J.W. Guidelines for the management of severe head injury. Brain Trauma Foundation. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 1996;3:109–127. doi: 10.1097/00063110-199606000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger H.G. Androgen production in women. Fertil. Steril. 2002;774(Suppl.):S3–S5. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)02985-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohan P. Wang C. McArthur D.L. Cook S.W. Dusick J.R. Armin B. Swerdloff R. Vespa P. Muizelaar J.P. Cryer H.G. Christenson P.D. Kelly D.F. Acute secondary adrenal insufficiency after traumatic brain injury: a prospective study. Crit. Care Med. 2005;33:2358–2366. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000181735.51183.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constant E.L. de Volder A.G. Ivanoiu A. Bol A. Labar D. Seghers A. Cosnard G. Melin J. Daumerie C. Cerebral blood flow and glucose metabolism in hypothyroidism: a positron emission tomography study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001;86:3864–3870. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.8.7749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csuka E. Morganti–Kossmann M.C. Lenzlinger P.M. Joller H. Trentz O. Kossmann T. IL-10 levels in cerebrospinal fluid and serum of patients with severe traumatic brain injury: relationship to IL-6, TNF-alpha, TGF-beta1 and blood–brain barrier function. J. Neuroimmunol. 1999;101:211–221. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis A.M. Haselkorn M.L. Vagni V.A. Garman R.H. Janesko–Feldman K. Bayir H. Clark R.S. Jenkins L.W. Dixon C.E. Kochanek P.K. Hemorrhagic shock after experimental traumatic brain injury in mice: effect on neuronal death. J. Neurotrauma. 2009;26:889–899. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai D. March R. Watters J.M. Hyperglycemia after trauma increases with age. J. Trauma. 1989;29:719–723. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198906000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dossett L.A. Swenson B.R. Evans H.L. Bonatti H. Sawyer R.G. Serum estradiol concentration as a predictor of death in critically ill and injured adults. Surg. Infect. 2008a;9:41–48. doi: 10.1089/sur.2007.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dossett L.A. Swenson B.R. Heffernan D. Bonatti H. Metzger R. Sawyer R.G. May A.K. High levels of endogenous estrogens are associated with death in the critically injured adult. J. Trauma. 2008b;64:580–585. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31816543dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. Better bootstrap confidence intervals. J. Amer. Statistical Assoc. 1987;82:171–185. doi: 10.1080/10618600.2020.1714633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. Tibshirani R. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman & Hall; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Evans M.J. Livesey J.H. Ellis M.J. Yandle T.G. Effect of anticoagulants and storage temperatures on stability of plasma and serum hormones. Clin. Biochem. 2001;34:107–112. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(01)00196-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farace E. Alves W.M. Do women fare worse: a metaanalysis of gender differences in traumatic brain injury outcome. J. Neurosurg. 2000;93:539–545. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.4.0539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farin A. Marshall L.F. Lessons from epidemiologic studies in clinical trials of traumatic brain injury. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 2004;89:101–107. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0603-7_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul M. Xu L. Wald M.M. Coronado V. Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations and Deaths, 2002–2006. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; Atlanta: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher R.A. On the mathematical foundations of theoretical statistics. Philos.Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A. 1922;222:309–368. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia–Segura L.M. Veiga S. Sierra A. Melcangi R.C. Azcoitia I. Aromatase: a neuroprotective enzyme. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;71:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasco V. Prodam F. Pagano L. Grottoli S. Belcastro S. Marzullo P. Beccuti G. Ghigo E. Aimaretti G. Hypopituitarism following brain injury: when does it occur and how best to test? 2010. Pituitary [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Guennoun R. Meffre D. Labombarda F. Gonzalez S.L. Deniselle M.C. Stein D.G. De Nicola A.F. Schumacher M. The membrane-associated progesterone-binding protein 25-Dx: expression, cellular localization and up-regulation after brain and spinal cord injuries. Brain Res. Rev. 2008;57:493–505. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildreth A.N. Mejia V.A. Maxwell R.A. Smith P.W. Dart B.W. Barker D.E. Adrenal suppression following a single dose of etomidate for rapid sequence induction: a prospective randomized study. J. Trauma. 2008;65:573–579. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31818255e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan M.A. Aging, injury and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1994;719:285–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb56836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurn P.D. Macrae I.M. Estrogen as a neuroprotectant in stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2000;20:631–652. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200004000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]