Abstract

Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1) is a neuron-specific enzyme that has been identified as a potential biomarker of traumatic brain injury (TBI). The study objectives were to determine UCH-L1 exposure and kinetic metrics, determine correlations between biofluids, and assess outcome correlations in severe TBI patients. Data were analyzed from a prospective, multicenter study of severe TBI (Glasgow Coma Scale [GCS] score ≤8). Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum data from samples taken every 6 h after injury were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). UCH-L1 CSF and serum data from 59 patients were used to determine biofluid correlations. Serum samples from 86 patients and CSF from 59 patients were used to determine outcome correlations. Exposure and kinetic metrics were evaluated acutely and up to 7 days post-injury and compared to mortality at 3 months. There were significant correlations between UCH-L1 CSF and serum median concentrations (rs=0.59, p<0.001), AUC (rs=0.3, p=0.027), Tmax (rs=0.68, p<0.001), and MRT (rs=0.65, p<0.001). Outcome analysis showed significant increases in median serum AUC (2016 versus 265 ng/mL*min, p=0.006), and Cmax (2 versus 0.4 ng/mL, p=0.003), and a shorter Tmax (8 versus 19 h, p=0.04) in those who died versus those who survived, respectively. In the first 24 h after injury, there was a statistically significant acute increase in CSF and serum median Cmax(0–24h) in those who died. This study shows a significant correlation between UCH-L1 CSF and serum median concentrations and biokinetics in severe TBI patients, and relationships with clinical outcome were detected.

Key words: biomarkers, clinical trial, neural injury, outcome measures, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

In the United States alone, approximately 2 million people, including many young children, adolescent males, and elderly people, experience a traumatic brain injury (TBI) each year (Bruns and Hauser, 2003). Despite significant recent progress in the management of severely brain-injured patients, it is still difficult to quantify the extent of primary brain injury and ongoing secondary brain damage, apart from the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score or the initial computed tomography (CT) scan. Therefore, biologic markers that reliably reflect the extent of brain damage and can easily be measured (i.e., in peripheral blood), continue to be explored (Ingebrigtsen and Romner, 2002; Papa et al., 2008).

A promising candidate biomarker for TBI currently under investigation is ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1) protein. This protein was previously used as a histological marker for neurons due to its high abundance and specific expression in neurons. UCH-L1 is involved in either the addition or removal of ubiquitin from proteins that are destined for metabolism (via the ATP-dependent proteasome pathway; Tongaonkar et al., 2000), thus playing an important role in the removal of excessive, oxidized, or misfolded proteins, during both normal and neuropathological conditions in neurons (Gong and Leznik, 2007).

In a recent study researchers reported that levels of UCH-L1 in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) were significantly increased in severe TBI patients compared to control subjects, with a significant association between levels of UCH-L1 in CSF and injury severity measures, including GCS, evolving lesions on CT, and 6-week mortality (Papa et al., 2010). Similarly, UCH-L1 levels were also found to be elevated in CSF from patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, surgically-induced circulation arrest, and a small set of severe TBI patients (n=9) (Lewis et al., 2010; Siman et al., 2008, 2009). However, measurement of CSF biomarkers requires placement of ventricular catheters, which is invasive and not always possible, and moreover, may influence CSF protein levels (Berger et al., 2002; Kruse et al., 1991). Since UCH-L1 is highly specific to the neuron, the highest concentrations would be expected to be found in the CSF, and lesser amounts in the serum, due to distribution to and from the CSF.

For the first time, our study evaluates UCH-L1 levels in both CSF and serum in patients after severe head injury. The objectives were to investigate: (1) the exposure and kinetic metrics of UCH-L1, using a quantitative ELISA analysis; and (2) the correlation between exposure and kinetic metrics in the CSF and serum, and biofluid kinetics and 3-month mortality.

Methods

Study design

This is a biokinetic analysis of UCH-L1 CSF (n=59) and serum (n=86) patient data from parallel prospective multicenter studies of severe TBI conducted between 2003 and 2005 at the University of Florida Trauma System (Shands Hospital in Gainesville and Jacksonville), and the University Hospital of Pécs. The clinical studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Florida, and by the Regional Research Ethics Committee of the Medical Center, Pécs, respectively. Written informed consent was obtained from next of kin because all eligible patients were in coma within 24 h from admission. Adult patients with severe head injury as defined by a GCS score of ≤8, and requiring a ventricular catheter for intracranial pressure monitoring, were enrolled in the studies. Initial computed tomography (CT) scans obtained on admission were analyzed according to the classification of Marshall and associates (Marshall et al., 1991). There were 15 patients included in this analysis that were also included in our previous publication (Papa et al., 2010), but the samples for these patients were rerun using the new and improved assay described below. Patients requiring CSF drainage for other medical reasons (CSF, n=26), or healthy volunteers (serum, n=166), were used as control patients for biokinetic comparisons. All patient identifiers were kept confidential by the principal investigators at each institution; unidentifiable patient study codes were used for all data provided for kinetic analysis at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Sample collection

CSF samples were obtained every 6 h up to a maximum of 7 days following TBI. CSF samples from severe TBI subjects were collected directly from the ventriculostomy catheters, which were placed as a standard of care for severe TBI patients at these institutions. During the first 24 h after admission, the sample times varied for each patient due to differences between injury time and admission, as well as time to ventriculostomy placement. Thereafter, samples were collected approximately every 6 h on a standardized schedule. Approximately 3–4 mL of CSF was collected from each subject at each sample point. The samples were immediately centrifuged for 10 min at 5000g to separate CSF from blood cells, and immediately frozen and stored at −70°C until the time of analysis.

Serial blood samples (5–10 mL) obtained every 6 h up to a maximum of 7 days were collected in serum separator tubes. Blood in tubes was then allowed to clot at room temperature for 30–60 min, before being centrifuged for 45,000g at room temperature for 5–7 min. Then 500-μL aliquots of cleared serum (supernatant) were pipetted into 1.8-mL barcoded cryovials and snap-frozen on dry ice before being stored at −80°C until use.

Of the 95 patients who had samples available for analysis, serum samples were available for 86 patients; 59 of the 86 patients also had CSF samples available for analysis. Therefore, only those samples from the 59 patients with both serum and CSF samples were used for determining correlations between biofluids. In addition, a limited number of outcome data were available for the study patients (serum n=54; CSF n=44), and included in the outcome correlations with the serum (n=86) and CSF (n=59) patients.

Biomarker analysis methods

Serum and CSF sample concentrations of UCH-L1 were measured using a standard UCH-L1 sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) protocol (Liu et al., 2010; Papa et al., 2010). Both mouse monoclonal antibody (capture antibody) and rabbit polyclonal antibody (detection antibody) were made in-house against recombinant human UCH-L1 full-length protein. Both were affinity-purified using a target-protein-based affinity column. Their specificity to only target protein (UCH-L1) was confirmed by immunoblotting. Reaction wells were coated with capture antibody (500 ng/well purified mouse monoclonal anti-human UCH-L1) in 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate (pH 9), and incubated overnight at 4°C. The plates were then emptied and 300 μL/well blocking buffer (Startingblock T20-TBS) was added and incubated for 30 min at ambient temperature with gentle shaking. Antigen standard (UCH-L1 standard curve: 0.05–50 ng/well), unknown samples (3–10 μL CSF or 30 μL of serum), or assay internal control samples were then added. After the plate was incubated for 2 h at room temperature, it was washed using an automatic plate washer (each well was rinsed with 5×300 μL wash buffer [TBST]). Detection antibody (rabbit polyclonal antihuman UCH-L1-HRP conjugation, made in-house at 50 μg/mL) in blocking buffer was then added to the wells at 100 μL/well, and the plates were further incubated at room temperature for 1.5 h. After additional automatic washing, biotinyl-tyramide solution (Perkin Elmer Elast Amplification Kit; Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA) was added, and the plate was incubated for an additional 15 min at room temperature, followed by automatic washing. Streptavidin-HRP (1:500, 100 μL/well) in PBS with 0.02% Tween 20 and 1% BSA was added and incubated for 30 min at room temperature, followed by automatic washing. Finally, the wells were developed with substrate solution: Ultra-TMB ELISA 100 μL/well (#34028; Pierce Protein Research Products, Rockford, IL) with incubation for 5–30 min, then read at 652 nm with a 96-well spectrophotometer (Spectramax 190; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The lower limit of detection for this assay was 0.01 ng/mL for CSF and 0.1 ng/mL for serum. As negative controls, we noted that if anti-UCH-L1 capture or detection antibodies were substituted with non-immune normal IgG (mouse) or (rabbit), respectively, no target signals were detected.

Both anti-UCH-L1 mouse monoclonal antibody (capture antibody), and rabbit polyclonal antibody (detection antibody), were affinity purified using a target-protein-based affinity column. Detection antibody was then HRP-conjugated. Their specificity to only target protein (UCH-L1) was confirmed by immunoblotting, as we previously reported (Liu et al., 2010). We also showed that UCH-L1 target protein is highly enriched and specific to brain tissue, with only very minor expression detected in kidney, skeletal muscle, testes, and large intestine (Fig. 1A). In addition, the selection of this antibody pair for sandwich ELISA was based on vigorous combination screening of many candidate antibodies or clones to ensure they covered distinct epitopes, as well as worked well together in a sandwich ELISA format.

FIG. 1.

Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1) brain specificity and antibody-based immunoblotting detection of UCH-L1 following severe traumatic brain injury (TBI). (A) UCH-L1 shows strong brain enrichment and specificity among various human tissues. (B) UCH-L1 was also detected and elevated in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF; 6 and 24 h) from two randomly-selected TBI patients (TBI-1 and TBI-2) in comparison to three separate CSF controls (Con) by immunoblotting. Polyclonal antibody was used, but monoclonal antibody also produced similar results.

We have previously shown that in animal TBI studies, UCH-L1 protein was found to be detectible and elevated in rat CSF (Liu et al., 2010). Similarly, using immunoblotting with the polyclonal anti-UCH-L1 antibody, we examined a few selected patients with CSF samples at 6 h and at 24 h, as well as several non-brain-injury CSF controls. Figure 1B shows representative immunoblots demonstrating human UCH-L1 (the intact 24-kDa form) detected and elevated in the CSF (6 and 24 h) from two TBI patients in comparison to three separate CSF controls. We did not detect any noticeable breakdown products. We attempted the same detection method with human TBI serum or plasma samples, but due to the lower UCH-L1 levels and high protein content in serum/plasma, UCH-L1 protein cannot be readily detected by immunoblotting. We thus turned to sandwich ELISA for its sensitivity and quantitative characteristics. This sandwich ELISA format has been previously described and validated (Liu et al., 2010).

Exposure metrics and kinetic analysis

Exposure metrics describe the amount and duration of biomarker exposure, and the metrics evaluated in this study were acute (first 24 h after injury) and subacute (first 7 days after injury) area under the curve (AUC), mean residence time (MRT), maximum concentration (Cmax), and time to maximum concentration (Tmax). Half-life (t½) was the kinetic metric evaluated in this study, and it describes the rate of decline of the biomarker in the CSF and serum. These exposure and kinetic metrics were determined for each biomarker, and provide a better understanding of the changes that occur over time. AUC quantifies the amount of biomarker present, and MRT describes the average amount of time the biomarker is present in the biofluid during the study period. Cmax and Tmax identify the biomarker's peak concentration and the time it takes to achieve this peak concentration. Half-life provides quantitative data on the time it takes for the biomarker concentrations to decline by at least 50% in the biofluid evaluated, allowing for an estimate of how long it takes to eliminate the biomarker from the biofluid if no other injury occurs.

Non-compartmental kinetic calculations as described in Pharmacokinetics (Gibaldi and Peirrier, 1982) were used to determine AUC, MRT, and t½ for UCH-L1 in both the CSF and serum. The linear trapezoidal rule was used to calculate the AUC and area under the first moment curve (AUMC) from the first to last observed time point. MRT was calculated from AUC and AUMC (MRT=AUMC/AUC), and was used to describe the average duration of exposure of UCH-L1 in the biofluids. If the AUC and AUMC were zero, then MRT was unable to be determined and was not included in the MRT analyses. The rate constant for decline (λ) was estimated from log linear regression of 2 or more points between which at least a 50% decrease in concentration occurred. The half-life of UCH-L1 was calculated using the rate constant for decline [t½=ln(2)/λ]. Due to the highly variable concentrations of the biomarkers in the biofluids, the sample time points for calculating the rate constant for decline could occur at any time during the study period. In addition, only patients with detectable CSF and serum UCH-L1 concentrations that decreased by at least 50% during the study period were included in the half-life kinetic analysis. Therefore, half-life could not be determined for all patients. UCH-L1 Cmax and Tmax were determined from the observed CSF and serum concentrations. Patients that did not have concentrations greater than the level of detection were unable to be included in the Tmax analyses, since Cmax was “zero” and occurred at multiple time points. Kinetic equations used to determine these exposure and kinetic characteristics can be found in Table 1. The concentration of UCH-L1 in each patient prior to brain injury and ventriculostomy catheter placement was unknown, and concentrations for control patients were approaching zero; therefore, zero was used as the baseline level for analysis. In addition, all concentrations below the limit of detection were imputed as zero. Patients without ventriculostomy catheters were not included in the CSF kinetic analysis. In addition, the number of UCH-L1 CSF samples varied per patient due to early discontinuation of the ventriculostomy catheter if it was medically unnecessary or the patient expired.

Table 1.

Kinetic Equations Used to Determine Biomarker Exposure and Kinetic Metrics

| AUCtrap(tn)=sum i=1 to n ((ci+ci–1)*(ti–ti–1)/2) |

| AUMCtrap(tn)=sum i=1 to n ((ci*ti+ci–1*ti–1)*(ti–ti–1)/2) |

| MRT=AUMCtrap/AUCtrap |

| t1/2=ln(2)/lambda |

AUC, trapezoidal area under the curve; AUMC, trapezoidal area under the first moment curve; MRT, mean residence time.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe biokinetic metrics in both the CSF and serum and are expressed as medians with interquartile range. The Mann-Whitney U or the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to evaluate biokinetic metric differences based on GCS and clinical outcome. The correlation between the biokinetic properties of UCH-L1 in CSF and serum was performed using Spearman's rank correlation. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was constructed to assess cutoff values for predicting measures that would distinguish TBI from control patients. Sensitivity and specificity were maximized by selecting optimal cutoff values. Significance was set at p<0.05 (JMP® Version 8.0 software; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Of the 95 patients enrolled in the clinical study, biokinetic analysis was conducted on serum samples from 86 patients and CSF samples from 59 patients. UCH-L1 CSF and serum biokinetic data from 59 patients who had both samples available were used to determine correlations between biofluids. The demographic data for TBI patients and controls can be found in Table 2. As a comparison to the complete study group, demographics for patients that did not have UCH-L1 serum concentrations above the limits of detection (n=16) were also evaluated separately. These patients had a median GCS score of 6 (range 3–8), were 88% male, and had a median age of 42 years (SD 13 years). The majority of patients had data available from the time of injury until 3 days post injury. Exposure and kinetic metrics for both CSF and serum were determined from concentrations over the 7-day study period, unless otherwise stated.

Table 2.

Patient Demographics for Patients Included in the Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) and Serum Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) Biokinetic Analyses

|

TBI (CSF) n=59 |

Control (CSF) n=26 |

TBI (serum) n=86 |

Controls (serum) n=166 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 38±20 | 57±17 | 36±19 | 37±14 |

| Male, % | 72 | 70 | 74 | 57 |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | 12 | 24 | 27 | 133 |

| African American | 4 | 8 | 26 | |

| Other | 2 | 3 | 7 | |

| Not available | 41 | 2 | 48 | |

| ED GCS, median (range) | 3 (3–8) | 15 | 3 (3–8) | |

| Mechanism of injury | ||||

| Motor vehicle | 11 | 23 | ||

| Motor cycle | 2 | 4 | ||

| Fall | 4 | 3 | ||

| Assault | 0 | 3 | ||

| Other | 4 | 5 | ||

| Not available | 38 | 48 | ||

| Marshall classification | ||||

| Diffuse injury II | 1 | 1 | ||

| Diffuse injury III | 13 | 13 | ||

| Diffuse injury IV | 1 | 1 | ||

| EML | 14 | 14 | ||

| Not available | 30 | 57 | ||

| Procedure (controls): | ||||

| Lumbar puncture | 12 | |||

| Intraventricular placement | 12 | |||

| Not available | 2 | |||

| CSF drain rationale (controls): | ||||

| Hydrocephalus | 20 | |||

| Cyst (colloid, subarachnoidealis) | 2 | |||

| Other | 2 | |||

| Not available | 2 | |||

| Alcohol | 116 | |||

| Drug | 19 | |||

| Smoke | 53 | |||

| Health | ||||

| Excellent | 78 | |||

| Good | 74 | |||

| Average | 13 | |||

| Not available | 1 | |||

Data were not available for all patients and control cases. There were 4 TBI patients for whom no GCS data were available.

SD, standard deviation; ED, emergency department; GCS, Glasgow Comal Scale; EML, evacuated mass lesion.

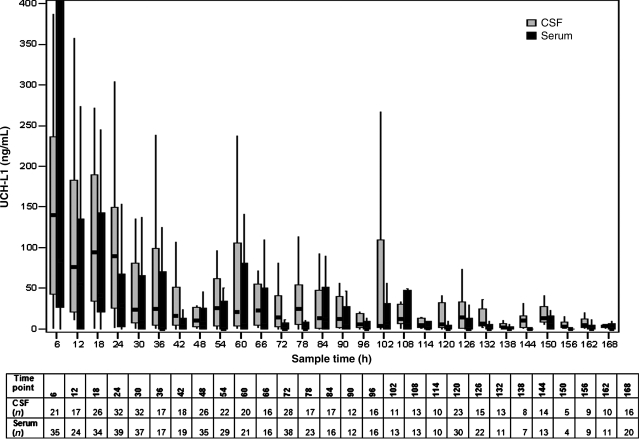

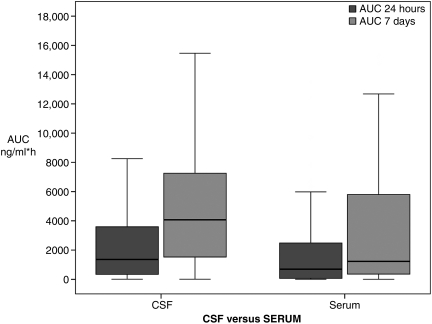

The temporal profile for UCH-L1 rounded to the nearest standardized 6-h time point over the 7-day period is shown in Figure 2. There was a significant overall correlation between median concentrations of UCH-L1 in CSF and serum (rs=0.59, p<0.001). CSF and serum exposure and kinetic metrics are reported in Table 3. The majority (61%) of the UCH-L1 total AUC for serum was observed acutely (within 24 h post-injury), whereas only 34% of the CSF total AUC was observed in this same time period (Fig. 3). UCH-L1 median AUC and Cmax were greater and median Tmax and MRT were prolonged in the CSF compared to serum (p<0.001). However, there were significant correlations between CSF and serum for median AUC (rs=0.3, p=0.027), Tmax (rs=0.68, p<0.001), and MRT (rs=0.65, p<0.001) over the 7-day study period. In addition, the correlation coefficient for median AUC(0–24h) over the first 24 h after injury was rs=0.57 (p<0.001), for Cmax(0–24h), was rs=0.60 (p<0.001), and for Tmax(0–24h) was rs=0.50 (p<0.001). The median half-life of UCH-L1 was similar in both CSF and serum.

FIG. 2.

Temporal profiles for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1) median concentrations at standardized 6-h time points up to 7 days post-injury (rs=0.59, p<0.001). Control median concentrations are shown for comparison. Data were not available for all patients at all time points, and the sample size for each time point is listed in the grid below the graph. Correlations between CSF and serum were performed using Spearman's rank correlation. The line in the box indicates the median value of the data, the upper edge of the box indicates the 75th percentile of the data set, and the lower edge indicates the 25th percentile. The ends of the vertical lines indicate the minimum and maximum data values.

Table 3.

Ubiquitin C-Terminal Hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1) Exposure and Kinetic Metrics in the Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) and Serum of Traumatic Brain Injury Patients

| CSF | Serum | Correlation coefficient (p value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (ng/mL*h) | n=59 | n=86 | 0.3 |

| Mean (SD) | 5892 (7115) | 46 (74) | (p=0.027) |

| Median (range) | 4053 (6–36,958) | 11 (0–416) | |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | n=59 | n=86 | 0.23 |

| Mean (SD) | 148 (122) | 2.71 (4.76) | (p=0.094) |

| Median (range) | 105.9 (0.7–468.2) | 0.71 (0–27.21) | |

| Tmax (hours) | n=59 | n=70 | 0.68 |

| Mean (SD) | 30 (32) | 22.05 (31.96) | (p<0.001) |

| Median (range) | 18 (3–135) | 8.71 (1.48–167.42) | |

| MRT (hours) | n=59 | n=70 | 0.65 |

| Mean (SD) | 40.77 (23.57) | 28.19 (32.84) | (p<0.001) |

| Median (range) | 36.72 (6.8–99.7) | 14.23 (1.83–167.42) | |

| Half-life (hours) | n=8 | n=41 | 0.03 |

| Mean (SD) | 11 (12) | 13 (11) | (p=0.90) |

| Median (range) | 7(0.1–55) | 9 (2–55) |

These metrics were determined using concentrations over the 7-day study period. Correlations between CSF and serum were performed using Spearman's rank correlation.

AUC, area under the curve; Cmax, maximum concentration; Tmax, time to maximum concentration; MRT, mean residence time; SD, standard deviation.

FIG. 3.

Median ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1) area under the curve (AUC) for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum dichotomized by time in traumatic brain injury (TBI) patients. AUC 24 hours describes the area under the curve for 0–24 hours after injury. Total AUC represents the total area under the curve over the 7-day study period. The AUC 24 hours was 34% of the total AUC for CSF and 61% of the total AUC for serum. AUC is expressed in ng/mL*h. The line in the box indicates the median value of the data, the upper edge of the box indicates the 75th percentile of the data set, and the lower edge indicates the 25th percentile. The ends of the vertical lines indicate the minimum and maximum data values.

No significant exposure or biokinetic differences were identified between males and females over the 7-day study period. Median biokinetic results for CSF comparisons between females and males, respectively, were as follows: AUC 4838 versus 3274 ng/mL*h (p=0.5); Cmax 114 versus 100 ng/mL (p=0.4); MRT 45 versus 36 h (p=0.4); and half-life 7 versus 7 h (p=0.8). However, there was a trend towards an increase in median CSF Tmax of female versus male patients (females 27 h versus males 14 h, p=0.056). The median biokinetic serum characteristics for females and males, respectively, were as follows: AUC 16 versus 10 ng/mL*h (p=0.2); Cmax 1.4 versus 0.5 ng/mL (p=0.2); Tmax 13 versus 8 h (p=0.50); MRT 15 versus 14 h (p=0.8); and half-life 9 versus 9 h (p=0.8).

When compared to control patients, there was a statistically significant higher median Cmax in the CSF and serum in the TBI patients (p<0.001; Table 4). Using a serum Cmax cut-off of >0.11 ng/mL, the ROC area was 0.83 (p<0.0001), and was highly sensitive (0.81) and specific (0.73) for determining TBI. The results of the ROC analysis also showed that Cmax was even more sensitive (0.80) and specific (1) for predicting TBI in the CSF (Cmax cut-off of >34 ng/mL, ROC area of 0.95 [p<0.0001]).

Table 4.

Comparison of Ubiquitin C-Terminal Hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1) Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) and Serum Median Cmax Concentrations in Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) Patients to Their Respective CSF and Serum Controls

| |

CSF Cmax |

Serum Cmax |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCH-L1 (ng/mL) | Control | TBI | Control | TBI |

| n | 26 | 59 | 166 | 86 |

| Median | 1.25 | 105.8 | 0 | 0.71 |

| IQR | 0.36–5.12 | 43.8–236.2 | 0–0.18 | 0.16–2.7 |

| p Value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

There was a significant difference between Cmax in patients with traumatic brain injury and control patient single-point concentrations. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine differences between groups.

Cmax, maximum concentration; IQR, interquartile range.

When comparing exposure and kinetic metrics over the 7-day study period, and neurological status as evaluated by the GCS score, the CSF UCH-L1 Tmax was significantly decreased in those with GCS scores 3–5 (n=41) versus those with a higher GCS score (n=18) over the 7-day study period, but there were no differences in the 24-h post-injury comparisons (Table 5). However, analysis of UCH-L1 metrics in the serum showed a significant increase in serum UCH-L1 AUC and Cmax, and a shorter Tmax in those that had GCS scores of 3–5 (n=62), compared to those with a GCS score of 6–8 (n=24). These differences were also significant when evaluated in the acute period 24 h post-injury. There were no significant differences in the percentage of patients who died by 3 months post-injury for those with GCS scores of 3–5 and those with GCS scores of 6–8 (CSF: 45% [n=13] versus 20% [n=3], p=0.097; Serum: 53% [n=20] versus 25% [n=4], p=0.057; respectively).

Table 5.

Comparisons of Ubiquitin C-Terminal Hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1) Biokinetic Metrics and Dichotomized Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) Scores Over the 7-Day Study Period and Acutely

| |

|

Over 7 days |

|

0–24 h post-injury |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCS 6–8 | GCS 3–5 | p Value | GCS 6–8 | GCS 3–5 | p Value | ||

| AUC (ng/mL*h) | CSF | 3391 | 4782 | 0.27 | 937 | 2302 | 0.08 |

| Serum | 3 | 25 | <0.001 | 0 | 12 | <0.001 | |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | CSF | 98 | 157 | 0.08 | 84 | 158 | 0.08 |

| Serum | 0.23 | 1.8 | <0.001 | 0 | 1.6 | <0.001 | |

| Tmax (h) | CSF | 26 | 14 | 0.04 | 16 | 12 | 0.10 |

| Serum | 13 | 6 | 0.03 | 13 | 7 | 0.04 | |

| MRT (h) | CSF | 46 | 32 | 0.06 | |||

| Serum | 16 | 14 | 0.18 | ||||

| t½ (h) | CSF | 6.3 | 7 | 0.09 | |||

| Serum | 6 | 9 | 0.28 | ||||

GCS represents scores documented upon admission to the emergency department. Serum metrics were significantly different in patients with worse GCS scores. The Mann-Whitney u test was used to determine differences between groups.

AUC, area under the curve; Cmax, maximum concentration; Tmax, time to maximum concentration; MRT, mean residence time; t½, half-life.

Associations between biofluid exposure metrics and biokinetics and outcome at 3 months (dead or alive) were also determined for those patients for whom outcome data were available (Table 6). There was no significant difference between the CSF median AUC, Cmax, Tmax, MRT, or t½ (using data from the first 7 days post injury) when comparing survivors (n=28) and those that died (n=16); however, there was a trend towards an increased median Cmax(0–7 days) in those that died (175 versus 100 ng/mL, p=0.056). Analysis of UCH-L1 serum exposure and biokinetic parameters (over the 7-day study period) and outcomes showed a statistically significant increase in median AUC and Cmax, and a shorter Tmax, in those who died (n=24) versus those who survived (n=30). Evaluation of only the acute post-injury period (24–72 h after injury) also showed a statistically significant increase in CSF and serum median Cmax(0–24h), in serum median AUC(0–24h), and in CSF and serum median AUC(0–72h) (CSF: 4782 versus 1845 ng/mL*h, p=0.045; Serum: 19 versus 4 ng/mL*h, p=0.014), in those that died versus those that survived at 3 months. Figure 4 shows the temporal profiles of the median UCH-L1 standardized 6-h time points for survivors versus non-survivors.

Table 6.

Comparisons of Biokinetic Metrics and Outcomes over the 7-Day Study Period and Acutely Post-Injury

| |

|

Over 7 days |

|

0–24 h post-injury |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survivors | Non-survivors | p Value | Survivors | Non-survivors | p Value | ||

| AUC (ng/mL*h) | CSF | 3685 | 4809 | 0.17 | 615 | 2302 | 0.07 |

| Serum | 4 | 34 | 0.006 | 1 | 15 | 0.003 | |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | CSF | 100 | 175 | 0.056 | 44 | 158 | 0.04 |

| Serum | 0.4 | 2 | 0.003 | 0.23 | 1.9 | 0.002 | |

| Tmax (h) | CSF | 21 | 14 | 0.26 | 14 | 12 | 0.87 |

| Serum | 19 | 8 | 0.035 | 13 | 9 | 0.24 | |

| MRT (h) | CSF | 41 | 36 | 0.74 | |||

| Serum | 32 | 18 | 0.21 | ||||

| t½ (h) | CSF | 5 | 7 | 0.23 | |||

| Serum | 14 | 9 | 0.16 | ||||

Outcome data were only available for a limited number of patients (CSF: survivors n=28, non-survivors n=16; Serum: survivors n=30, non-survivors n=24). The Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine differences between groups.

AUC, area under the curve; Cmax, maximum concentration; Tmax, time to maximum concentration; MRT, mean residence time; t½, half-life.

FIG. 4.

Median cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1) standardized 6-h time points for the 7-day study period for those that survived (CSF n=28; serum n=30), versus non-survivors (CSF n=16; serum n=24), at 3 months post-injury. These differences over time resulted in statistically significant differences in serum UCH-L1 biokinetics in those who had poor outcomes. Data were not available for all patients at all time points. The line in the box indicates the median value of the data, the upper edge of the box indicates the 75th percentile of the data set, and the lower edge indicates the 25th percentile. The ends of the vertical lines indicate the minimum and maximum data values.

To determine if the GCS influenced outcome, the exposure and kinetic metric analyses for those that survived versus those that died were adjusted for dichotomized GCS. This analysis showed that serum UCH-L1 Cmax (0–7 days) independently predicts mortality regardless of GCS score (p=0.045).

Discussion

UCH-L1 is a potential biomarker of TBI (Papa et al., 2010), and exposure and kinetic metrics in both the CSF and serum of severe TBI patients was characterized for the first time in this study. The results of this analysis show increases in UCH-L1 concentrations in both the CSF and serum of severe TBI patients compared to control patients, as well as differences in the exposure and kinetic metrics in the CSF and serum compartments. Although these biokinetic differences exist, there appears to be a strong correlation between CSF and serum concentrations over time. This study provides critical characteristics of UCH-L1 that may influence the sampling strategy for future clinical trials in TBI patients.

Although every patient did not have samples available for each time point, evaluation of the UCH-L1 over a 7-day period in both CSF and serum showed a strong correlation between the median concentrations over time. This is an encouraging result, as it suggests the possibility of using less invasive serum monitoring to predict CSF changes in UCH-L1 exposure. The amount of UCH-L1 in CSF and serum over time is represented by AUC, which can account for fluctuations over time that may not be captured by serial post-injury time point comparisons. The strong correlation between CSF and serum AUC adds additional support for the possibility of using only serum samples for analysis of this biomarker.

UCH-L1 AUC, Cmax, Tmax, and MRT were always greater in the CSF compared to serum over the 7-day study period. The median Tmax and MRT were over twice as long in the CSF, with CSF and serum median time to maximum concentrations (Tmax) occurring at approximately 18 and 9 h post-injury, respectively. Interestingly, the percentage of the total AUC(0–7 days) that occurred within the first 24 h post-injury was greater in the serum than the CSF. These exposure differences may be due to changes in distribution of UCH-L1 from rapid repair of the blood–CSF barrier post-injury. The half-life (used to help characterize the rate of decline) of UCH-L1 was similar in both CSF and serum, ranging from 7 to 9 h. Based on these exposure and kinetic characteristics, UCH-L1 concentrations would be expected to peak in the acute period and decrease rapidly over approximately the next 48 h in patients with an isolated injury and no secondary injury. This is an encouraging result, suggesting clinically-feasible monitoring time points for UCH-L1.

There was a strong correlation between all biofluid metric and kinetic parameters, except for Cmax (rs=0.23, p=0.094), over the 7-day period. In addition, the correlations between CSF and serum AUC, Cmax, and Tmax in the acute period 24 h after injury were all statistically significant. These strong exposure and kinetic metric correlations between the two compartments also support the possibility of using a minimally-invasive approach (i.e., peripheral serum sampling) to determine UCH-L1 changes in the CSF.

Since data exist that suggest progesterone may be neuroprotective (Wright et al., 2001, 2007), we also evaluated the UCH-L1 exposure and kinetic differences between females and males. There were no significant differences found; however, females tended to take a longer time to reach maximum CSF concentrations. Larger studies evaluating biomarker changes based on gender need to be conducted.

To assess UCH-L1 as a potential biomarker of severe TBI, we evaluated differences when compared to control patients. There was a 70- to 85-fold higher median Cmax in the serum and CSF, respectively, compared to the median control concentrations. There was also a high sensitivity and specificity for detecting differences between groups as shown by the ROC area analysis. These results support the data presented by Papa and associates, suggesting that UCH-L1 is a potential biomarker of severe TBI. (Papa et al., 2010).

Further analyses were done to compare exposure and kinetic metrics in patients with variable GCS scores and outcomes. In patients with a worse GCS score on admission (GCS 3–5), serum exposure and kinetic metrics were significantly different over the 7-day study period, as well as acutely post-injury, compared to those with a GCS score of 6–8. The patients with GCS scores of 3–5 had more UCH-L1 observed over time, and had higher maximum concentrations that developed more quickly, as well as acutely after injury, compared to those with GCS scores of 6–8. There were no significant differences over time in the exposure and kinetic metrics in the CSF, except when evaluating the 7-day data for Tmax. This showed a shorter time to reach maximum concentrations in those with worse GCS scores in the first 24 h post-injury, similarly to what was found for serum.

These differences were similar to what was found when exposure and kinetic metrics were evaluated based on outcome. There were no statistically significant differences found between median CSF UCH-L1 exposure and kinetic metrics over the 7-day period in those that died versus survival at 3 months, but there were statistically significant increases in median serum AUC and Cmax and a shorter Tmax in those that died. There were also significant increases in acute serum UCH-L1 AUC from admission to 24 h, CSF and serum Cmax from admission to 24 h, and AUC from admission to 3 days post-injury, in those that died. When comparisons of exposure and kinetic metrics were adjusted for GCS, serum Cmax (over 7 days) was the only independent predictor of outcome. These results for the acute post-injury time period are similar to what was found when evaluating mean UCH-L1 CSF concentrations during the first 24 h post-injury and 6-week outcomes in our previous study (Papa et al., 2010). Therefore, acute changes in UCH-L1 may be the most important with regard to predicting outcome.

The similar biokinetic changes of those seen in patients with a poor GCS score upon admission and those with a poor outcome at 3 months support the use of UCH-L1 for severe TBI. The statistically significant differences detected for exposure and kinetic metrics in the serum, but not the CSF, in those with a worse GCS score, and those that died versus those that survived, may have been due to the larger number of serum samples available for analysis over the 7-day period. Larger studies are needed to confirm these interesting findings and to elucidate the potential role of UCH-L1 as a biomarker for TBI.

Conclusion

This is the first study to determine the biokinetics of UCH-L1, a potential biomarker of TBI, in serum and CSF of severe TBI patients. UCH-L1 CSF and serum maximum concentrations were significantly greater than in control patients, and there were strong correlations between CSF and serum exposure and kinetic characteristics, especially during the acute period. Serum exposure metrics were more likely than CSF to correlate with survival at 3 months post-injury, and may be a less invasive way to determine biomarker changes in TBI patients. Further studies of UCH-L1 should be conducted to support these associations with outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by Department of Defense Award number DoD W81XWH-06-1-0517, and National Institutes of Health Award number R01 NS052831.

Author Disclosure Statement

Drs. Robicsek, Gabrielli, Brophy, and Papa are consultants of Banyan Biomarkers, Inc. Dr. Mondello is an employee of Banyan Biomarkers, Inc. Drs. Wang and Hayes own stock, receive royalties from, and are officers of Banyan Biomarkers Inc., and as such may benefit financially as a result of the outcomes of this research or work reported in this publication.

Disclaimer

Material has been reviewed by the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. There is no objection to its presentation and/or publication. The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors, and are not to be construed as official, or as reflecting true views of Department of the Army or Department of Defense.

References

- Berger R.P. Pierce M.C. Wisniewski S.R. Adelson P.D. Clark R.S. Ruppel R.A. Kochanek P.M. Neuron-specific enolase and S100B in cerebrospinal fluid after severe traumatic brain injury in infants and children. Pediatrics. 2002;109:E31. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.2.e31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns J., Jr. Hauser W.A. The epidemiology of traumatic brain injury: a review. Epilepsia. 2009;44(Suppl. 10):2–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.44.s10.3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibaldi M. Peirrier D. Pharmacokinetics. 2nd. Marcel Dekker, Inc.; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Gong B. Leznik E. The role of ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 in neurodegenerative disorders. Drug News Perspect. 2007;20:365–370. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2007.20.6.1138160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingebrigtsen T. Romner B. Biochemical serum markers of TBI. J. Trauma. 2002;52:798–808. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200204000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse A. Cesarini K.G. Bach F.W. Persson L. Increases of neuron-specific enolase, S-100 protein, creatine kinase and creatine kinase BB isoenzyme in CSF following intraventricular catheter implantation. Acta Neurochir. (Wien.) 1991;110:106–109. doi: 10.1007/BF01400675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis S.B. Wolper R. Chi Y.Y. Miralia L. Wang Y. Yang C. Shaw G. Identification and preliminary characterization of ubiquitin C terminal hydrolase 1 (UCHL1) as a biomarker of neuronal loss in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Neurosci. Res. 2010;88:1475–1484. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M.C. Akinyi L. Scharf D. Mo J. Larner S.F. Muller U. Oli M.W. Zheng W. Kobeissy F. Papa L. Lu X.C. Dave J.R. Tortella F.C. Hayes R.L. Wang K.K.W. Ubiquitin-C-terminal hydrolase as a biomarker for ischemic and traumatic brain injury in rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2010;31:722–732. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07097.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall L.F. Marshall S.B. Klauber M.R. van Berkum-Clark M. A new classification of head injury based on computerized tomography. J. Neurosurg. 1991;75:S14–S20. [Google Scholar]

- Papa L. Akinyi L. Liu M.C. Pineda J.A. Tepas J.J., 3rd Oli M.W. Zheng W. Robinson G. Robicsek S.A. Gabrielli A. Heaton S.C. Hannay H.J. Demery J.A. Brophy G.M. Layon J. Robertson C.S. Hayes R.L. Wang K.K. Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase is a novel biomarker in humans for severe traumatic brain injury. Crit. Care Med. 2010;38:138–144. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b788ab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa L. Robinson G. Oli M. Pineda J. Demery J. Brophy G.M. Robicsek S.A. Gabrielli A. Robertson C.S. Wang K.K. Hayes R.L. Use of biomarkers for diagnosis and management of traumatic brain injury. Expert Opin. Med. Diagn. 2008;28:1–9. doi: 10.1517/17530059.2.8.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siman R. Roberts V.L. McNeil E. Dang A. Bavaria J.E. Ramchandren S. McGarvey M. Biomarker evidence for mild central nervous system injury after surgically-induced circulation arrest. Brain Res. 2008;1213:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siman R. Toraskar N. Dang A. McNeil E. McGarvey M. Plaum J. Maloney E. Grady M.S. A panel of neuron-enriched proteins as markers for traumatic brain injury in humans. J. Neurotrauma. 2009;26:1867–1877. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.0882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tongaonkar P. Chen L. Lambertson D. Ko B. Madura K. Evidence for an interaction between ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes and the 26S proteasome. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;20:4691–4698. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.13.4691-4698.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright D.W. Bauer M.E. Hoffman S.W. Stein D.G. Serum progesterone levels correlate with decreased cerebral edema after traumatic brain injury in male rats. J. Neurotrauma. 2001;18:901–909. doi: 10.1089/089771501750451820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright D.W. Kellerman A.L. Hertzberg V.S. Clark P.L. Frankel M. Goldstein F.C. Salomone J.P. Dent L.L. Harris O.A. Ander D.S. Lowery D.W. Patel M.M. Denson D.D. Gordon A.B. Wald M.M. Gupta S. Hoffman S.W. Stein D.G. ProTECT: a randomized clinical trial of progesterone for acute traumatic brain injury. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2007;49:391–402. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.07.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]