Abstract

This paper evaluates theoretical claims linking relational uncertainty about a relationship partner to experiences of stress during interactions with that partner. Two observational studies were conducted to evaluate the association between relational uncertainty and salivary cortisol in the context of hurtful and supportive interactions. In Study 1, participants (N = 89) engaged in a conversation about core traits or values with a partner, who was trained to be hurtful. In Study 2, participants (N = 89) received supportive messages after completing a series of stressful tasks and receiving negative performance feedback. As predicted, partner uncertainty was associated with greater cortisol reactivity to the hurtful interaction in Study 1. Contrary to expectations, Study 1 results also indicated that self uncertainty was associated with less cortisol reactivity, when self, partner, and relationship uncertainty were tested in the same model. Study 2 revealed that relational uncertainty dampened cortisol reactions to performing poorly on tasks while the partner observed. As predicted, Study 2 also found that partner uncertainty was associated with less cortisol recovery after the supportive interaction, but neither self nor relationship uncertainty was associated with rate of cortisol change during the recovery period.

Keywords: relational uncertainty, stress, cortisol, emotional support, hurt

Uncertainty in the context of interpersonal interactions generally refers to an inability to predict and explain a communication partner’s behavior (Berger, 1997). Early conceptions of uncertainty, based on uncertainty reduction theory, focused on questions about communication partners and how an interaction would proceed during initial interpersonal interactions (Berger & Calabrese, 1975). More recent research has examined relational uncertainty, which is the degree of confidence people have in their perceptions of involvement in a relationship (Knobloch & Solomon, 1999). According to Knobloch and Solomon, relational uncertainty stems from three sources: doubts individuals have about their own involvement in the relationship (self uncertainty); questions about a partner’s participation in the relationship (partner uncertainty); and ambiguity about the status or future of the relationship itself (relationship uncertainty). Relational certainty exists when people clearly understand their own commitment to the relationship, when they are confident in their perceptions of a partner’s involvement (or lack thereof), and when they have few doubts about the enduring or fleeting nature of the association; relational uncertainty occurs when individuals are unclear about these aspects of the relationship.

Empirical evidence indicates that relational uncertainty complicates interactions with romantic partners. Individuals who are unsure about their relationship lack well-defined expectations for behavior, which makes conversations with a partner more difficult, more frustrating, and less meaningful (Knobloch & Solomon, 2005). Relational uncertainty has also been linked to more intense experiences of negative emotions, including anger, sadness, and fear (Knobloch, Miler, & Carpenter, 2007), both in general (Knobloch, Miller & Carpenter, 2007) and in response to particular events or stimuli (Knobloch & Solomon, 2002, 2003). Furthermore, people experiencing relational uncertainty tend to report experiencing more jealousy and perceiving more threats to the relationship (Afifi & Reichert, 1996; Knobloch, Solomon, & Cruz, 2001; Theiss & Solomon, 2006a). Perhaps not surprisingly, individuals experiencing relational uncertainty are also more likely to describe their relationship as unsteady or unstable (Knobloch, 2007).

Theoretical perspectives on uncertainty, in general, also imply that doubts about interpersonal relationships can be stressful. For example, uncertainty reduction theory describes uncertainty as an aversive state that people want to reduce (Berger & Calabrese, 1975). The theory of motivated information management claims that a discrepancy between the amount of uncertainty an individual desires versus the amount they experience causes anxiety that motivates information seeking (Afifi & Weiner, 2006). Similarly, empirical tests of anxiety/uncertainty management theory (Gudykunst, 1995) have shown that uncertainty is positively associated with anxiety across a variety of relationships and cultures (Gudykunst & Nishida, 2001). These theories point to various forces that can alleviate uncertainty, including opportunities to interact with another person and information seeking activities; however, the theories cohere in their assumption that uncertainty can be an aversive experience.

Although empirical evidence and theoretical logic suggest that uncertainty creates discomfort for communicators, we know of no research that has evaluated whether relational uncertainty is associated with physiological stress. The lack of research on this topic leaves untested the link between uncertainty and stress implied in extant theory. Evaluating the physiological consequences of relational uncertainty also responds to Brashers’ call for research that addresses “the range of behavioral and psychological responses to uncertainty” ( Brashers, 2001, p. 477). More generally, examining how cognitive states of uncertainty interface with physiological outcomes speaks to the mind-body connection that frames peoples’ interpretation of and responses to relationship events. Finally, because stress hormones, such as cortisol, are associated with a variety of negative mental and physical health outcomes (see Lovallo, 1997; Rabin, 1999), an examination of how relational uncertainty influences cortisol reactions to relationship events provides insight into the impact of social relationships on health.

What facets of engagement with a romantic partner are likely to produce a physiological stress response that is tied to relational uncertainty? As noted previously, Knobloch and Solomon (2005) found that relational uncertainty made communication about positive, negative, and surprising events more challenging. To the extent that uncertainty undermines both message production and processing (Berger, 1997), we expect relational uncertainty to affect the full spectrum of communication episodes involving the romantic partner. To provide a broad test of the association between relational uncertainty and physiological stress responses, we focused this investigation on two divergent communication events: (a) hurtful messages, which can induce stress, and (b) emotionally supportive messages, which can reduce stress. In the following section, we describe the stress response and the ways in which relational uncertainty may exacerbate stress. We then elaborate on our thinking with respect to hurtful and supportive messages from a dating partner, and we report two studies testing our logic.

Physiological Stress and Relational Uncertainty

The physiological stress response is initiated when an individual perceives a threat to the self that is negative or incongruent with the individual’s goals, and the person believes he or she will have difficulty coping with the threat (Sapolsky, 1998). The anticipation or perception of a threat activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA), one of multiple critical pathways in the stress response, resulting in the release of cortisol (for a more complete discussion of the stress response see Loving, Heffner, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2006). The trajectory of the stress response is an increase in stress hormones in response to a perceived threat (reactivity), which stabilizes or tapers off as the threat is mitigated (recovery; see Cannon, 1929; Selye, 1976). Although cortisol mobilizes energy to respond to a stressor, prolonged elevation of cortisol is associated with a multitude of negative health outcomes, including increased susceptibility to infectious diseases, cardiovascular problems, obesity, and cancer (Kiecolt-Glaser, Glaser, Gravenstein, Malarkey, & Sheridan, 1996; Lovallo, 1997; Padget & Glaser, 2003; Rabin, 1999). Thus, incorporating measures of cortisol reactivity and recovery within research on personal relationships may provide insight into the long-term health consequences of relationship phenomena.

Cortisol has benefits as a marker of stress reactivity and recovery because of its accessibility. Cortisol can be measured through saliva, which provides an unobtrusive and objective measure of internal changes during a potentially stressful event that cannot be reliably measured through self-reports. Previous research suggests that individuals experience stress as an undifferentiated feeling (see Cacioppo, Marshal-Goodell, & Gormezano, 1983; Cacioppo, Tassinary, Stonebraker, & Petty, 1987), making self-reporting of stress difficult. Consequently, self-report measures of stress may not be associated with biological indicators of stress (see Kirschbaum, Klauer, Filipp, & Hellhammer, 1995; van Eck, Nicolson, Berkhof, & Sulon, 1996). By measuring cortisol at multiple points before, during, and after an event, we can examine how factors impact the intensity of reactions to the episode and impede or expedite recovery after the event, and we can capture health-relevant aspects of the stress response that individuals may not be consciously aware of or able to self-report accurately.

We hypothesize that relational uncertainty may exacerbate physiological stress responses to a variety of relationship events. Although we know of no studies that have empirically tested this claim, the characteristics and outcomes associated with relational uncertainty provide evidence to support the proposition. First, relational uncertainty stems from doubts or questions an individual has about the nature of a relationship (relationship uncertainty) or their own (self uncertainty) or their partner’s involvement in that relationship (partner uncertainty). These ambiguities make interactions with a partner more unpredictable and uncontrollable, which are factors that heighten physiological stress responses (Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004). Specifically, uncertainty may lead to a lack of perceived epistemic control, or the ability to predict what will happen and whether goals will be attained, which is associated with heightened anxiety (Miceli & Castelfranchi, 2005). Combined with the negative emotions associated with relational uncertainty, including sadness, fear, and anger (Knobloch, Miller, & Carpenter, 2007), we expect that relational uncertainty magnifies stress during interactions with a relationship partner.

Second, research suggests that conversations that highlight relational uncertainty are associated with cortisol change. In particular, Loving, Gleason, and Pope (2009) assessed how varying levels of experience thinking and talking about marriage (i.e., marriage novelty) influenced individuals’ cortisol responses to discussing the probability of marriage with a dating partner. Results showed that individuals with greater marriage novelty had more elevated cortisol reactions to discussing the chance of marriage with their partner than did individuals who had thought or talked about marriage with their partner prior to the study. Loving et al. speculated that the increased reactivity to the conversation occurred because individuals who hadn’t previously discussed the possibility of marriage with their partner experienced more uncertainty about how they or their partner felt about the future of the relationship. Although the study did not measure relational uncertainty, per se, it suggests that conversations that accentuate or highlight questions about a relationship can provoke a cortisol response.

Relational Uncertainty and Stress Responses to Hurtful and Supportive Messages

To this point, we have proposed that relational uncertainty makes interactions with romantic partners more difficult, leading to heightened cortisol responses. To test this logic, we consider the association between relational uncertainty and cortisol changes in the context of two distinct communication episodes. Hurtful messages are a common occurrence in romantic relationships, which can lead to negative outcomes including relational distancing, decreased intimacy and relationship satisfaction, and increased likelihood of relationship dissolution (e.g., Feeney, 2004; Leary & Springer, 2001; Mills, Nazar, & Farrell, 2002). In contrast, emotional support can strengthen relationships and enhance relationship satisfaction (Cohen & Syme, 1985; Cutrona, Russell, & Gardner, 2005). Moreover, emotional support is associated with cardiovascular, endocrine, and immune changes that may have implications for health outcomes (Uchino, Cacioppo, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 1996), and greater well-being across a variety of chronic health conditions (see Helgeson & Cohen, 1996; Rook & Underwood, 2000; Seeman, 2001). The following sections examine these communication episodes and the role of relational uncertainty therein.

Hurt, Relational Uncertainty, and Stress

Hurt is a feeling of emotional injury (Folkes, 1982), which generally results from statements or behaviors that convey rejection (Fitness, 2001) or relational devaluation (Leary, Springer, Negel, Ansell, & Evans, 1998). Hurtful messages can be a source of stress because they threaten positive mental models of the self and others (Feeney, 2005), signal a discrepancy between what an individual believes to be true and what others communicate, and violate expectations for the relationship (Bachman & Guerrero, 2006). Previous research on contexts that are conceptually similar to hurt provide insight into the potential for hurt to elicit a cortisol response. First, social evaluative threats, such as rejection, criticism, and exclusion, were a primary predictor of cortisol responses to lab-based tasks (Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004). Similarly, withdrawal, which can be interpreted as passive rejection, is associated with greater physiological responsiveness (see Loving, Le, & Crockett, 2009). Because hurt is a negative emotion that can elicit feelings of emotional pain, hurtful interactions are likely to create physiological reactions similar to those experienced in response to pain (Eisenberg, Lieberman, & Williams, 2003).

Recent studies suggest that relational uncertainty may exacerbate the biological response to hurtful interactions. Individuals experiencing greater relational uncertainty evaluate hurtful interactions as more intensely hurtful, more intentional, and more damaging to the relationship (Theiss, Knobloch, Checton, & Magsamen-Conrad, 2009). Similarly, McLaren, Solomon, and Priem (in press), found that partner and relationship uncertainty predicted greater relational turbulence, which was positively associated with the intensity of negative emotions and severity of hurt that participants associated with hypothetical hurtful scenarios. Thus, doubts about involvement in a relationship constitute a feature of relationships that amplifies reactions to potentially hurtful events.

Based on this evidence, and our general assumption that relational uncertainty exacerbates the stress response to interactions with a romantic partner, we predict that all three sources of relational uncertainty will intensify cortisol responses to a hurtful interaction. Although our reasoning suggests the three facets of relational uncertainty have a uniform association with the cortisol response, unique results associated with self uncertainty have been documented in prior research. In particular, self uncertainty diverges from partner and relationship uncertainty in its associations with perceptions of relational turbulence and hurt, such that partner and relationship uncertainty were indirectly associated with greater perceptions of hurt by increasing perceptions of turbulence, leading to increased experience of hurt, whereas self uncertainty had a direct negative effect on perceived hurt (McLaren, et al., in press). Similarly, Theiss and Solomon (2006b) found that people experiencing self-uncertainty were more direct in confronting partners about relationship irritations, whereas partner and relationship uncertainty inhibited direct communication about problems. Although these findings imply that people’s own lack of conviction within a relationship may buffer them from the anxieties that accompany uncertainty, we lack a strong theoretical argument for expecting divergent patterns for the three facets of relational uncertainty. Thus, we advance the following hypothesis:

H1: Cortisol reactions in response to hurtful messages from a dating partner are positively associated with (a) self uncertainty, (b) partner uncertainty, and (c) relationship uncertainty.

Emotional Support, Relational Uncertainty, and Stress

Emotional support or comforting includes expressions of care, concern, assurance, or encouragement that are intended to alleviate or lessen the emotional distress of others (Burleson, 1985, 2003; Cutrona & Russell, 1990). Supportive messages can help individuals reappraise a stressful situation, leading to emotional improvement (Jones & Wirtz, 2006). Support can also facilitate faster physiological recovery after a stressful event. For example, satisfaction with spousal support is associated with lower blood pressure and cortisol levels after a conflict interaction (Heffner, Kiecolt-Glaser, Loving, Glaser, & Malarkey, 2004). Thus, emotional support may protect individuals from the harmful effects of stress or assist in recovery after a stressful event.

Previous research suggests that relational uncertainty may reduce the stress buffering effects of emotional support. Research on ambivalent relationships, which are characterized by both high positivity and high negativity, has shown that support provided by a person the support receiver feels ambivalent about is associated with greater cardiovascular responses to a stressor (Uchino, Holt-Lunstad, Uno, & Flinders, 2001; Uno, Uchino, & Smith, 2002). Uchino et al. suggest that interactions with ambivalent network members may be stressful due to unpredictability in the relationship. Similarly, Uno et al. state that support attempts by an ambivalent friend may be less effective because the negative feelings associated with that friend may cause the support receiver to question the sincerity of the support. In the context of relational uncertainty, Knobloch, Miller, Bond, et al. (2007) theorized that relational uncertainty may cause individuals to interpret messages more harshly or critically (see also McGregor, Zanna, Holmes, & Spencer, 2001). Consistent with this assertion, Knobloch et al. found that relational uncertainty was negatively associated with individuals’ perception of affiliation and involvement in a spouse’s message and was positively associated with people’s perceptions of self and relationship threat when discussing a surprising event. Questions about involvement in a relationship have also been shown to reduce an individual’s ability to interpret cues of intimacy and liking (Knobloch & Solomon, 2005). To the extent that relational uncertainty makes interpreting support attempts more difficult or reduces people’s ability to attend to positive relational cues, we expect that self, partner, and relationship uncertainty mitigate the positive effects of supportive communication. More specifically:

H2: Cortisol recovery in response to supportive messages from a dating partner is negatively associated with (a) self uncertainty, (b) partner uncertainty, and (c) relationship uncertainty.

Method

To test our predictions, we conducted two observational studies of dating dyads interacting in a laboratory setting. In Study 1, one individual in the dyad discussed core traits or values with their partner, who was instructed to be hurtful during the discussion. In Study 2, one member of the dyad completed a series of stressful tasks, received negative performance feedback, and discussed the feedback with their partner, who was instructed to be either neutral or supportive during the interaction. In both studies, participants’ self-reported relational uncertainty and we collected salivary cortisol as a measure of stress reactivity (Study 1) or recovery (Study 2).

In both studies, participants were recruited from introductory communication courses at a large eastern university. Potential participants completed a screening questionnaire, and the samples included individuals who: (a) were in a dating relationship with a partner who was geographically close and willing to attend the research session with them, (b) reported they were not diagnosed with or experiencing depression or an anxiety disorder, and (c) were not taking prescription medication. Participants who reported taking oral contraceptives (Study 1 n = 39; Study 2 n = 43) were not excluded because, given the prevalence of birth control use in college dating females, excluding these women would reduce the general applicability of our findings.

Participants earned 2% credit in the course for the completion of the study or an alternative assignment. The students’ partners attended the research session as volunteers, and they were not compensated for their participation. Both individuals provided informed consent, and the partners could refuse to participate in research procedures without penalty to the student. Because the partners were not compensated for participation, they engaged in limited procedures, whereas the participants completed all of the research procedures, including questionnaires and saliva samples. All of the data collection sessions were completed between 2:00 p.m. and 7:00 p.m. to minimize the effect of time of day on cortisol levels (Kirschbaum & Hellhammer, 1989).

In testing our hypotheses, we conducted parallel analyses of the data from the two studies to facilitate comparisons across the two relationship phenomena we investigated. In particular, we evaluated the role of participant sex in both sets of analyses, because of documented sex differences in both experiences of hurt (e.g., Feeney & Hill, 2006; Miller & Roloff, 2005) and emotional support (Burleson, Holmstrom, & Gilstrap, 2005). Likewise, theoretical perspectives on uncertainty, in general (e.g., uncertainty reduction theory; Berger, 1997), and empirical studies (e.g., Knobloch & Solomon, 2003) suggest that the length of a relationship affects people’s experiences of uncertainty; consequently, we examined relationship length as a covariate in both studies. Finally, because we argue that relational uncertainty influences cortisol responses independent of people’s subjective experiences of hurt and support, Studies 1 and 2 include perceptions of the hurt and support, respectively, within the analyses. To promote comparability of findings between the two studies, these variables are included in both sets of analyses if they are statistically significant covariates in either study.

Study 1

To provide a test of H1, Study 1 examined the association between relational uncertainty and cortisol reactivity in the context of hurtful interactions.

Participants

The sample included 89 participant/partner dyads, from which 89 individuals (47 males, 42 females) constituted the target participants. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 24 (M = 20.01, SD = 1.07). The majority of the sample self identified as Caucasian (n = 83; Native American, n = 1; Asian, n = 2; Hispanic, n = 2; “other,” n = 1). All participants reported being in a “serious” heterosexual dating relationship, with the length of involvement ranging from 1 month to 6.50 years (M = 22.83 months, SD = 18.52 months).

Procedures

To limit the impact of external factors on cortisol levels (see Kirschbaum & Hellhammer, 1989), participants received an email prior to their research session that asked them not to eat, drink caffeine or alcohol, or use tobacco products one hour prior to arrival at the lab and not to exercise on the day of research participation. At the research session, participants completed another screening questionnaire, and individuals who had engaged in these behaviors (n = 6) were asked to reschedule their appointment. For participants who met the screening criteria, salivary cortisol was collected, approximately 15 minutes after participants arrived at the lab, as an initial measure of stress. All research personnel were trained in and followed procedures for bloodborne pathogens. Cryovials (Salimetrics, State College, PA) were used to collect saliva samples using a passive drool procedure. Participants were asked to imagine they had food in their mouth and begin to chew to increase the production of saliva. When they felt saliva in their mouth, they spit it into a plastic tube.

Next, participants completed a short questionnaire soliciting demographic information. The final question on the initial questionnaire asked participants to list three traits or values that they considered especially important to them or central to their identity. The specific wording of the question was,

Many people have personal characteristics that are especially important to them. Although you probably have a lot of traits, beliefs, or attitudes that you could describe, we would like you to think about traits and values that you feel are central to who you are. These could be parts of your identity, personality traits, abilities, or values and beliefs. On the lines below, list the three traits or values that you see as most important to who you are.

We elected to focus on personal traits or values that were especially salient to participants, in light of research indicating that people are hurt, at least in part, by messages that are critical or convey devaluation (e.g., Leary et al., 1998; Vangelisti, 1994; Vangelisti, Young, Carpenter-Theune, & Alexander, 2005). Participants then completed a second questionnaire, which included the measure of relational uncertainty.

Meanwhile, researchers reviewed the procedures for the dyadic interaction with the partner. Partners received note cards with the three traits or values the participant reported and were told that they would be engaging in two 5-minute conversations with the participant about two of the traits or values. Partners were allowed to choose which characteristics to discuss during the conversation because they needed to be comfortable with the topics and able to effectively bolster or discount those traits. In the first conversation, the partner was instructed to support and validate the participant’s statements and feelings. Specifically, the partner was given a prompt card that asked him or her to “agree that your partner has the trait/value, discuss times when they show that trait/value, say that the trait/value is important and you admire it, and agree with your partner’s statements.” For the second conversation, the partner was instructed to discuss the second trait or value in a manner that was disconfirming or hurtful. The researcher reviewed different types of hurtful messages with the partner to prepare him or her for the interaction. The partner was also given a prompt card for the second conversation that stated, “disagree that your partner has the trait/value, discuss times when they didn’t show the trait/value, say that the trait/value isn’t important, say that it isn’t a trait/value that you admire, and do not agree with your partner’s statements.” The two conversation procedure was designed so that the first conversation would provide time for the dyad to get comfortable interacting in the lab environment. The partner’s agreement with the first trait also creates an expectation within the participant that the session will go well. Furthermore, because the partner affirms the first trait, he or she gains credibility as a source of feedback, which may intensify the perception of hurt in the second conversation.

After the participant was finished with the second questionnaire and the partner was trained, the dyad was reunited to engage in the two 5-minute conversations, which were videotaped. The participant was told that he or she would be discussing two of the values that they identified earlier with their partner. The participant was given an index card with prompts to help the discussion stay focused on the values previously identified. The prompts asked participants to, “describe what the trait/value means to you, why this trait/value is important to you, and how the trait/value affects your decisions.” During the conversation, the researchers monitored the interaction from the control room with the intention of interrupting the conversation if the participant was perceived to be excessively upset; none of the conversations needed to be stopped. After the conversation, the partners were separated again and participants completed a final questionnaire about the interaction.

Two additional saliva samples were collected 20 and 30 minutes after the interaction to measure the biological response to the interaction. Research indicates that cortisol takes approximately 15 to 20 minutes to reach saliva after secretion from the adrenal glands (Stansbury & Gunnar, 1994). Thus, collecting saliva at both 20 and 30 minutes ensured that peak reactivity to the interaction would be captured. After collecting the final saliva sample, the dyad was debriefed. During the debriefing, the participant was told that their partner was trained to be disconfirming and hurtful, and that their behavior did not reflect their true feelings or beliefs. The researcher continued to describe the training until the participant fully understood the procedures used and he or she no longer reported any degree of upset. Before leaving, participants were given information about how to contact psychological services on campus and the principle investigator.

Measures

Salivary cortisol

The dependent variable in the study was salivary cortisol; one sample was collected as a baseline measure of cortisol, and two additional samples indexed reactivity to the interaction. The saliva samples were analyzed using commercially available salivary cortisol enzyme-linked immunoabsorbant assay (EIA) kits (Salimetrics, PA).1 The analysis yields a value, which is the number of micrograms of cortisol per deciliter of saliva, such that higher values reflect a higher concentration of salivary cortisol. The distribution of the cortisol measures was analyzed for normality and skew; two participants who were extreme outliers across all cortisol samples (± 3 SD) were excluded, resulting in a more normal distribution.

Relational uncertainty

Knobloch and Solomon’s (1999) measure of relational uncertainty was used to assess the participants’ self, partner, and relationship uncertainty. Participants indicated their level of agreement with statements that followed the question, “How certain are you about …?” Responses were recorded on a 6-point Likert-type scale (1 = completely or almost completely uncertain, 6 = almost or completely certain). The items were recoded so that higher values reflected greater uncertainty. The scores for items within subscales were averaged to form measures of self uncertainty (e.g., “… how much you like your partner,” and “… how important the relationship is to you,” M = 1.48, SD = 0.66, α = .88), partner uncertainty (e.g., “… whether or not your partner is ready to commit to you,” and “… whether or not your partner wants to be with you in the long run,” M = 1.58, SD = 0.78, α = .88), and relationship uncertainty (e.g., “… whether or not the relationship is a romantic one,” and “… whether or not it is a romantic or a platonic relationship,” M = 1.73, SD = 0.64, α = .83). Although the three measures were positively correlated (r’s ranged from .62 to .81), they were maintained as separate variables based on the theoretical characterizations of self, partner, and relationship uncertainty as distinct constructs (Berger & Bradac, 1982; Knobloch, 2007; Knobloch & Solomon, 2002) and a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), which showed a good fit to the data χ2 (41) = 114.57, χ2/df = 2.79, CFI = .92, RMSEA = .10. CFA results also showed that the three subscales did not form a unidimensional factor when the subscales were assigned to first-order factors and the first-order factor was assigned to a second-order factor, χ2 (44) = 328.79, χ2/df = 7.47, CFI = .68, RMSEA = .27, or when the subscale items were all assigned to a single factor, χ2 (44) = 198.06, χ2/df = 4.50, CFI = .83, RMSEA = .20.

Hurt

We followed procedures similar to those used by Vangelisti and Young (2000) to measure the self-reported intensity of hurt. Participants rated how hurtful the second interaction was (1 = not at all hurtful, 7 = extremely hurtful), how much emotional pain it caused (1 = no emotional pain, 7 = intense emotional pain), and how hurt they felt overall (1 = not at all hurt, 7 = extremely hurt. We averaged the responses to the three items (M = 3.26, SD = 1.52, α = .93).

Results

To begin, we evaluated the extent to which participants experienced the interactions as hurtful. First, we compared the degree of hurt reported by this sample to participants from a pilot study (N = 71) in which the partner provided supportive messages in both 5-minute interactions. Participants in the pilot study reported significantly less hurt (M = 1.28, SD = 0.64) than participants in this study (M = 3.26, SD = 1.52), t (148) = −6.53, p < .01. Second, we used paired sample t-tests to compare perceptions of the first conversation with the second conversation, in which the partner was instructed to be hurtful. Participants were asked to rate both conversations on the following 7-point semantic-differential scales: negative-positive, hurtful-supportive, dissatisfying-satisfying, and frustrating-calming, with higher values reflecting more positive traits. Relative to the first conversation, the second conversation was perceived as less positive (conversation 1 M = 6.40, SD = 0.95; conversation 2 M = 3.38, SD = 1.67; t (88) = 15.82, p < .001), less supportive (conversation 1 M = 6.48, SD = 0.84; conversation 2 M = 3.29, SD = 1.29; t (88) = 19.23, p < .001), less satisfying (conversation 1 M = 6.08, SD = 1.19; conversation 2 M = 3.36, SD = 1.52; t (88) = 13.21, p < .001), and less calming (conversation 1 M = 5.92, SD = 1.11; conversation 2 M = 2.85, SD = 1.28; t (88) = 16.47, p < .001). Ethical considerations limit the amount of hurt that can be elicited in an experimental setting, and we deemed the manipulation effective within these constraints.

To provide initial insight into our hypothesis, we examined correlations between the three measures of relational uncertainty and the three cortisol samples. The baseline measure of cortisol was not significantly correlated with either self uncertainty, r(89) = .15, ns, or partner uncertainty, r(89) = .18, ns; however, it was positively correlated with relationship uncertainty, r(89) = .20, p < .05. Consistent with H1, all three measures of relational uncertainty were positively and significantly associated with the two cortisol samples indexing reactivity to the hurtful interactions (r’s ranged from .21 to .38).

To test H1, we used 2-level hierarchical linear growth models (HLM 6.0). Level-1 is the within-person level that represents change in cortisol levels over time; Level-2 is the between-persons level in which person-level parameters predict differences in the individual growth trajectories. To test the effect of relational uncertainty on stress reactions to a hurtful interaction with a dating partner, we estimated a total of four models with cortisol as the dependent variable: one model included all of the relational uncertainty variables simultaneously and three additional models tested each component of relational uncertainty individually. We analyzed the relational uncertainty variables both in combination and individually for several reasons. First, prior research on relational uncertainty has used both strategies. In particular, studies using multiple regression analysis or multilevel modeling tend to assess the variables in separate models (e.g., Knobloch, Satterlee, & DiDomenico, 2010; Theiss et al., 2009; Theiss & Solomon, 2008), whereas studies employing structural equation modeling typically include all three facets of relational uncertainty as exogenous variables in one model (e.g., Theiss & Solomon, 2006b; McLaren et al., in press). Second, patterns in our data and extant research raise competing concerns about multicolinearity and statistical suppression. On one hand, the correlations between the facets of relational uncertainty suggest problems of multicolinearity, which can produce spurious results for individual variables when they are analyzed simultaneously. At the same time, the positive correlations among the facets of relational uncertainty could mask divergent associations with the dependent variable if the three facets of uncertainty are examined individually. Although we hypothesized uniform patterns of association for the three relational uncertainty variables, divergent effects associated with self uncertainty that have been documented in previous studies (Theiss & Solomon, 2006b; McLaren et al., in press) suggest a need to estimate the associations for each variable, with the other measures of relational uncertainty in the model. To provide the most informative analysis of the data, we evaluated the three relational uncertainty variables both in combination and within separate models.

For all of the models, the Level-1 model is represented by the following equation: Yti = π0i + π1i (time) + eti, where Yti is the cortisol score at time t for individual i. The intercept, π0i, represents the predicted baseline cortisol level. The slope, π1i, is the linear growth trajectory, which represents the coefficient for the relationship between the linear effect of time and cortisol reactivity for person i. Based on the timing of the cortisol samples, the time variable was coded as minutes from the baseline sample in ten minute increments; accordingly, time was coded 0, 4, 5, with 0 being the baseline sample. Finally, the residual component at time t for individual i is eti.

The Level-2 equations treat the intercept and the slope of the Level-1 equation as outcome variables. Thus, variables can be added to the intercept to predict differences between individuals in baseline cortisol levels and to the slope to predict differences in change in cortisol over time. In the combined model, the three relational uncertainty variables were included on the intercept and slope; in the models focused on each facet of relational uncertainty, only the relational uncertainty variable featured in each model was included on the intercept and slope. The variables on the intercept take into account the possibility that an individual’s stress level while anticipating participating in a research study with a dating partner could vary based on his or her self, partner, or relationship uncertainty. The relational uncertainty variables on the slope test how each facet of relational uncertainty is associated with reactivity to the hurtful interaction.

As discussed previously, participant’s sex was included as a predictor on both the intercept and slope to assess sex differences in cortisol responses to the interactions. Sex was coded 0 for males and 1 for females, and was grand mean centered so that the coefficients are interpretable as the average effect for the sample. We also examined whether relationship length was a significant predictor of the intercept or slope; because this variable was nonsignificant in both this and the subsequent study, it was removed from the model for parsimony. 2 Finally, we included individuals’ self-reported hurt in the equation predicting the intercept and slope of the model; by doing so, we evaluated the impact of relational uncertainty controlling for variation in the level of hurt individuals experienced, which allows us to estimate the unique variation in cortisol that is accounted for by the relational uncertainty variables.

The Level-2 model tested is as follows:

The first equation estimates sex, self, partner, and relationship uncertainty, and self-reported hurt as predictors of baseline cortisol, which is the intercept in the model. The second equation estimates the effects of sex, self uncertainty, partner uncertainty, relationship uncertainty, and self-reported hurt on slope of the model, which is change in cortisol across the three cortisol measurements. The models examining each facet of relational uncertainty individually were identical, except that the other two measures of relational uncertainty were omitted from both the intercept and the slope.

Coefficients for the multi-level models are reported in Table 1. Results for the equations predicting baseline cortisol point to a positive association between relationship uncertainty and participants’ cortisol prior to the dyadic interaction. In the combined model, this association approaches conventional levels of statistical significance; in the model evaluating relationship uncertainty separately, this association is significant at p < .05. None of the other predictors on the intercept were significant in either the combined model or in the models evaluating each relational uncertainty variable.

Table 1.

Relational Uncertainty Predicting Changes in Cortisol Over Time in Study 1

| Combined Model | Self Uncertainty | Partner Uncertainty | Relationship Uncertainty | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Cortisol | .127** (.045) | .144*** (.044) | .141** (.043) | .126** (.038) |

| Sex | .010 (.018) | .008 (.018) | .005 (.018) | .010 (.018) |

| Self-reported Hurt | −.012 (.008) | −.008 (.008) | −.007 (.008) | −.009 (.007) |

| Self Uncertainty | −.022 (.022) | −.024 (.014) | ||

| Partner Uncertainty | .009 (.014) | .023† (.013) | ||

| Relationship Uncertainty | .045† (.026) | .035* (.017) | ||

| Linear Slope | −.020* (.010) | −.015† (.010) | −.022* (.009) | −.020* (.009) |

| Sex | −.007 (.004) | −.006 (.004) | −.006 (.004) | −.005 (.004) |

| Self-reported Hurt | .004* (.002) | .004* (.002) | .004* (.002) | .004* (.002) |

| Self Uncertainty | −.008* (.001) | −.003 (.004) | ||

| Partner Uncertainty | .010* (.005) | .008* (.004) | ||

| Relationship Uncertainty | .002 (.007) | .005 (.004) |

Note: The dependent variable in the model is cortisol, which is measured in micrograms per deciliter (μg/dL). Cell entries are model coefficients; parenthetical values are standard errors. Sex is coded 0 = males, 1 = females and is grand mean centered.

< .10,

< .05,

< .01,

< .001.

For the equations predicting the slopes of the models, the coefficient for the intercept indicates that, controlling for the other variables in the models, individuals’ cortisol levels decreased across the three measurements; this trend was significant in three of the four analyses, and approached conventional levels of statistical significance in the model assessing self uncertainty. In all four analyses, participant’s sex was not significantly associated with the change in cortisol over time, but self-reported hurt was. In particular, the positive coefficient for self-reported hurt indicates that people who reported more hurt tended to have greater increases in cortisol across the three measurements.

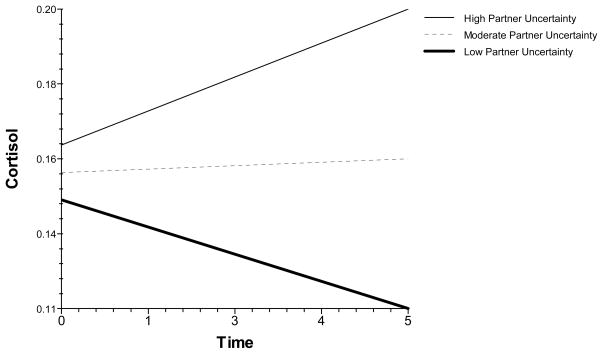

Our first hypothesis is tested by the coefficients for the relational uncertainty variables entered on the slope of the models. Results associated with self uncertainty differed between the combined model and the analysis focused exclusively on self uncertainty. When the other facets of relational uncertainty were included in the analysis, results showed a significant negative association between self uncertainty and rate of cortisol change. This finding indicates that, controlling for the effects of partner and relationship uncertainty, self uncertainty was associated with a decrease in cortisol. In the model analyzing self uncertainty individually, the coefficient was not statistically significant. These results run counter to H1a. In contrast, partner uncertainty was positively associated with cortisol change in both the combined model and the separate model. Consistent with H1b, these results indicate that individuals who were more uncertain about their partner’s feelings about the relationship experienced a significant increase in cortisol across the three cortisol measurements (see Figure 1). Contrary to H1c, relationship uncertainty was not associated with the rate of cortisol change in either the combined model or the model assessing this facet particular facet of relational uncertainty.

Figure 1.

Changes in Cortisol over Time as a Function of Partner Uncertainty in Study 1

Study 2

Our second hypothesis focused on the association between relational uncertainty and reactions to supportive, rather than hurtful, messages. In this study, we first induced a state of stress, and then examined cortisol recovery as a function of communication with a dating partner.

Participants

The sample contained 103 participants (41 males, 62 females), who ranged in age from 18 to 27 years (M = 20.39, SD = 1.97). Most of the participants reported being in a “serious dating relationship” (93.5%; “casual daters” n = 4). The length of relationship ranged from 1 week to 5.38 years (M = 6.03 months, SD = 7.03 months).

Procedures

Upon arriving at the lab, the dyad was separated and completed informed consent. As in Study 1, participants were also screened for factors that could artificially impact cortisol levels; individuals who met the screening criteria provided a baseline saliva sample.

Participant pre-interaction procedures

The participants’ pre-interaction activities included three parts: a questionnaire, stressor tasks, and performance feedback. First, participants completed a questionnaire, which collected demographic information and included the measure of relational uncertainty. Next, participants were introduced to a research confederate, whom they believed to be another student completing the study. The participant and confederate were placed across from each other at a table. They were told that they would be competing against each other on three tasks, and that performance at these tasks provided insight into their personal traits. They were also told that their dating partners were watching their performance from the other room, and that they would receive feedback on their performance, which they would discuss with their dating partner.

The three tasks included a number tracking task (see Schultheiss & Rohde, 2002; Wirth, Welsh, & Schultheiss, 2006), a timed typing task that was created for the purpose of this study, and a timed mental math task often used in the Trier Social Stress Test (a protocol used for the experimental induction of psychological stress; see Kudielka, Hellhammer, & Kirschbaum, 2007).3 The tasks, which are themselves stress provoking, were designed so that the confederate would consistently outperform the participant. The specific tasks were chosen because they included components shown to increase stress. Namely, the situation was novel, uncontrollable, and unpredictable, and the motivated performance tasks involved failure and social evaluation (see Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004; Kudielka, Hellhammer, Kirschbaum, 2007). In total, the tasks took approximately 20 minutes to complete.

Following completion of the tasks, the participant and confederate were separated and instructed to wait to receive their performance feedback. After 3 minutes, the researcher rejoined the participant. The researcher explained that the tasks had been used in previous research over the past 20 to 30 years and had been shown to be reliable and valid measures of a person’s traits (for example, participants were told that because people type words that are self-relevant faster than words that are irrelevant to their self-concept, the timed typing task measures people’s traits). The researcher then presented the performance feedback in a folder and explained the format of the results. The feedback, supposedly tailored to the participant, was written to indicate that the participant’s performance reflected negative personal qualities. The researcher instructed the participant to read the results well enough that he or she could explain them to the dating partner. Participants were told they would be given some time to review the feedback and then the partner would be brought in to begin the conversation.

Partner pre-interaction procedures

While the participant was completing the stressor tasks, the partner prepared for the conversation. The research assistant explained that the dyad would discuss how the participant felt while completing the tasks, what his or her feedback was, and how he or she felt about the feedback. To limit the impact of the partners’ evaluations of the relationship (including relational uncertainty) on their production of supportive messages and to ensure variation in levels of supportiveness within the sample, we randomly assigned partners to one of two conditions.

Roughly half of the partners were instructed to be impartial during the conversation, defined as refraining from offering personal opinions, feelings, or thoughts during the conversation. Partners were told to provide brief answers to questions the participant might ask, and then ask the participant a question to refocus the conversation away from the partner’s opinions. Partners were told that they should engage in the conversation as they normally would, with the exception of withholding their own perspective.

Partners in the other group were instructed to be as supportive as possible. Based on Jones and Guerrero’s (2001) manipulation of immediacy and person-centered messages, partners were asked to maintain eye contact, show nonverbal signs of listening, ask questions that probe how the tasks or feedback made the participant feel, validate the participant’s feelings, encourage the participant to elaborate on his or her feelings, try to get the participant to focus on positive aspects of him or herself, and communicate explicit statements that make the participant feel better about him or herself. The partners were also given examples of how each of these behaviors could be enacted.

Interaction

After the participant reviewed feedback on his or her performance, the dyad was reunited. The researcher explained that the pair was to discuss how the participant felt about the tasks, the contents of the feedback, and how the participant felt about the feedback. To standardize the conversations, the dyads were given a note card with prompt questions, which included, “what were your results on the tasks?”, “how did you compare to other college students?”, “how did you feel while completing the tasks?” and “how did you feel while you were reading your performance feedback on the tasks?” The dyad was given 8 minutes for the conversation, at which point they were separated to complete additional procedures. Previous research examining supportive communication has employed interaction intervals of 5 minutes (e.g., Barker & Lemle, 1984; Cousins & Vincent, 1983; Jones & Guerrero, 2001; Jones & Wirtz, 2006), whereas other research has utilized interaction intervals of up to 10 minutes (Fritz, Nagurney, & Helgeson, 2003). In this study, the 8-minute interval was chosen to give the dyad ample time to discuss the tasks and feedback without exhausting topics related to the research session.

Post-interaction procedures

Following the interaction, participants completed a questionnaire about their perceptions of the conversation. Then, the dyad was debriefed. The researcher explained the goal of the study and the procedures that were meant to induce a stress response, including the role of the confederate, the tasks, and the fabrication of the feedback. Finally, the researcher discussed how the tasks did not reflect the participant’s abilities or personality traits. The participant was allowed to ask questions until the purpose of the research procedures was understood and the participant stated that he or she was not upset.

Measures

Cortisol

Participants provided 6 saliva samples. The first sample was collected when the participants arrived at the lab as a baseline measure. Five additional saliva samples were collected after the conversation to index stress reactivity and recovery. Because cortisol takes approximately 15 to 20 minutes to reach saliva after secretion from the adrenal glands (Stansbury & Gunnar, 1994), each sample actually measures a participant’s cortisol level from 15 to 20 minutes earlier. For example, due to the time required to complete the tasks, feedback, and conversation, the second cortisol sample measures cortisol values while completing the tasks. The cortisol samples were timed to index phases of the stress process as detailed in Table 2.4 The patterns of reactivity to the stressful tasks and recovery after the interaction are substantiated by the positive linear trend from samples 1 to 3 and the negative linear trend from samples 3 to 6. The saliva samples were analyzed in the same manner as described in Study 1.

Table 2.

Study 2 Timing and Descriptive Statistics for Cortisol Samples

| Cortisol Sample | Timing of Cortisol | Name of Sample | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cortisol level prior to arriving at lab | Baseline | 0.13 (0.06) |

| 2 | Cortisol level during the middle of the stress tasks | Reactivity | 0.28 (0.16) |

| 3 | Cortisol level after receiving feedback, but before conversation | Completion | 0.26 (0.16) |

| 4 | Cortisol level 20 minutes after conversation | Initial Recovery | 0.22 (0.13) |

| 5 | Cortisol level 35 minutes after conversation | Recovery 2 | 0.18 (0.10) |

| 6 | Cortisol level 50 minutes after conversation | Final Recovery | 0.15 (0.09) |

Relational uncertainty

As in Study 1, Knobloch and Solomon’s (1999) measure of relational uncertainty was used to assess the participants’ self uncertainty (M = 1.73, SD = 0.87, α = .90), partner uncertainty (M = 1.63, SD = 0.91, α = .90), and relationship uncertainty (M = 2.10, SD = 0.93, α = .86). Again, the variables were positively correlated (r’s ranged from .45 to .68), but were retained as separate measures. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) showed a satisfactory fit to the data, χ2 (32) = 82.95, χ2/df = 2.59, CFI = .94, RMSEA = .09. CFA results also showed that the three variables did not form a unidimensional factor when the subscales were assigned to first-order factors and the first-order factor was assigned to a second-order factor, χ2 (36) = 211.65, χ2/df = 5.88, CFI = .80, RMSEA = .21, or when the subscale items were all assigned to a single factor, χ2 (33) = 309.92, χ2/df = 9.39, CFI = .69, RMSEA = .26.

Support effectiveness

Four 7-point semantic differential scales were used to measure perceptions of support effectiveness (as used in previous research, see Goldsmith & MacGeorge, 2000; Jones & Burleson, 1997). The questions asked participants to rate their partner’s behavior during the conversation on the following scales: appropriate-inappropriate, effective-ineffective, sensitive-insensitive, and helpful-unhelpful. The four items were recoded so that higher numbers reflect greater support effectiveness, and responses were averaged to create a composite measure of support effectiveness (M = 5.46, SD = 1.35, α = .92).

Perceptions of the interaction

Recall that some participants were instructed to maintain neutrality in the interaction, whereas others were asked to be supportive. To serve as a check of the interaction manipulation, a series of items assessed the participants’ perceptions of their partner’s messages during the interaction. Three items (“During the conversation, my partner made explicitly supportive comments,” “was clear about his or her opinion,” and “made directly supportive comments”) measured the explicitness of the partner’s supportive messages (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = undecided, 7 = strongly agree; M = 5.03, SD = 1.72, α = .89). Three items assessed perceived argument strength or elaboration of supportive messages: “During the conversation, my partner gave reasons why I shouldn’t feel bad,” “elaborated on his or her feelings or opinions,” and “gave examples that supported his or her opinion” (M = 4.42, SD = 1.82, α = .86).

Results

As a preliminary step, we conducted a series of t-tests comparing the neutral and supportive conditions to assess the effects of the experimental manipulation. Participants in the neutral condition rated their partners as being less explicit (M = 3.78, SD = 1.50) and conveying less argument strength (M = 2.90, SD = 1.47) than did participants in the supportive condition (explicitness M = 6.29, SD = 0.85; t(101) = −10.74, p < .001; argument strength M = 5.84, SD = 0.90; t(101) = −12.52, p < .001). Furthermore, compared to the neutral group, the supportive group rated the interaction higher in perceived support effectiveness (M = 6.37, SD = 0.62; neutral group M = 5.02, SD = 1.51; t(101) = −6.15, p < .001). These findings suggest that the manipulation was effective in creating variance in participants’ experience of supportiveness. Because self-reported support effectiveness is a more proximal predictor to isolate the effect of support on cortisol than is the interaction condition, and because supportiveness provides a continuous variable that enhances statistical power compared to the dichotomous manipulation, we included self-reported supportiveness in tests of the hypothesis.5

Whereas Study 1 assessed a projected increase in cortisol levels over three measurements, Study 2 involved activities designed to increase physiological stress and then decrease it. A piecewise growth model analysis is useful when distinct growth rates are predicted and changes in the growth rate are expected to occur at the same time for everyone in the sample (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). In this study, we expected that individuals would experience an increase in stress reflected in cortisol samples 1 to 3, which indexed stress reactivity associated with the tasks, and a decrease in stress reflected in cortisol samples 3 to 6, which indexed the recovery period and the interaction with the partner. Thus, we analyzed our data using 2-piece hierarchical linear growth curve models (HLM 6.0).

To measure the divergent changes, the Level-1 growth curve model included 2 linear slopes, rather than the single linear slope in the model evaluated in Study 1: Yti = π0i + π1i (pre-interaction time) + π2i (post-interaction time) + eti. The pre-interaction slope, π1i, indexes the degree of stress reactivity individuals experienced due to the tasks; the post-interaction slope, π2i, indexes stress recovery due to the interaction. As suggested in Raudenbush and Bryk (2002), two coding schemes were created to index each growth period of interest, pre-interaction and post-interaction. In each coding scheme, the third cortisol sample, representing cortisol levels after completing the tasks, was coded 0, making the intercept for the models the average cortisol values at the completion measurement, rather than at baseline. The remaining measurements were calculated as minutes from the completion cortisol measurement, in ten minute intervals. The pre-interaction slope was coded as −4.5, −1, 0, 0, 0, 0, which tests the change in cortisol values from samples 1 to 3. The post-interaction slope was coded as 0, 0, 0, 1.5, 3, 4.5, which tests the change in cortisol values from samples 3 to 6. The other variables in the models were specified in the same manner as that in Study 1.

In the Level-2 model, between-person variables were added to the intercept (π0i) to explain individual variation in completion cortisol levels, the pre-interaction slope (π1i) to predict individual differences in reactivity to the tasks, and the post-interaction slope (π2i) to predict individual differences in cortisol recovery. Paralleling the analyses conducted in Study 1, participant sex was included in all of the equations. In addition, relationship length was evaluated on the intercept and both slopes; because it was not a significant predictor of cortisol in either Study 1 or 2, it was removed from the models. Finally, we included the self-reported effectiveness of the support provided by the partner on the intercept and post-interaction slope because it was a characteristic of the conversation that could affect cortisol recovery. By doing so, the models evaluate how relational uncertainty impacts cortisol recovery, controlling for the level of support participants perceived. The Level-2 model tested was as follows:

As in Study 1, three additional models tested each facet of relational uncertainty individually.

The coefficients for the models are in Table 3. We observed a sex difference on the intercept, such that completion cortisol levels were lower for females than males; this coefficient was statistically significant in the combined model and in the analysis of self uncertainty, and it approached conventional levels of significance in the analyses of partner and relationship uncertainty. Not surprisingly, self-reported perceptions of a partner’s supportiveness during the interaction were unrelated to levels of cortisol upon completing the stressor tasks. Self uncertainty was negatively associated with completion cortisol levels, in both the combined and individual analyses, indicating that people who questioned their own involvement in their relationship exhibited a lower cortisol response to the stressor tasks. The coefficient for partner uncertainty was also negative at a level that approached significance in the analysis focused on partner uncertainty; however, this association was not significant in the combined model. In the combined model, relationship uncertainty had a positive association with completion cortisol levels that was marginally significant, but relationship uncertainty was not a significant predictor on the intercept when examined individually. In total, these findings suggest that the cortisol response to the stressor tasks was dampened among females and individuals reporting more self uncertainty.

Table 3.

Relational Uncertainty Predicting Changes in Cortisol Over Time in Study 2

| Combined Model | Self Uncertainty | Partner Uncertainty | Relationship Uncertainty | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completion Cortisol Sample | .300*** (.053) | .307*** (.055) | .268** (.042) | .257** (.046) |

| Sex | −.095* (.041) | −.096** (.041) | −.060† (.033) | −.063† (.035) |

| Support Effectiveness | −.002 (.004) | −.002 (.004) | −.003 (.004) | −.003 (.004) |

| Self Uncertainty | −.063* (.028) | −.048* (.023) | ||

| Partner Uncertainty | −.024 (.015) | −.027† (.014) | ||

| Relationship Uncertainty | .036† (.023) | −.015 (.014) | ||

| Pre-interaction Slope | .043*** (.009) | .043*** (.009) | .036*** (.007) | .035*** (.007) |

| Sex | −.015* (.008) | −.016* (.008) | −.007 (.007) | −.001 (.007) |

| Self Uncertainty | −.013* (.006) | −.012** (.005) | ||

| Partner Uncertainty | −.006† (.003) | (.003) | −.007* | |

| Relationship Uncertainty | .005 (.004) | −.001* (.003) | ||

| Post-interaction Slope | −.040** (.013) | −.039*** (.013) | −.041** (.001) | −.041** (.001) |

| Sex | .020** (.006) | .021*** (.006) | .018*** (.005) | .019** (.005) |

| Support Effectiveness | .001 (.002) | .001 (.002) | .002 (.002) | .002 (.002) |

| Self Uncertainty | .004 (.004) | .004 (.003) | ||

| Partner Uncertainty | .006* (.002) | .005** (.002) | ||

| Relationship Uncertainty | −.003 (.003) | .003 (.002) |

Note: The dependent variable in the model is cortisol, which is measured in micrograms per deciliter (μg/dL). Cell entries are model coefficients; the parenthetical values are standard errors. Sex is coded 0 = males, 1 = females and is grand mean centered.

< .10,

< .05,

< .01,

< .001.

The equation predicting the pre-interaction slope reflects factors that affected the rate of cortisol change prior to the participant’s interaction with the dating partner. In all four models, the main effect of the pre-interaction slope was significant and positive, indicating that cortisol levels generally increased from baseline through the third cortisol sample. The combined model and the individual analysis of self uncertainty revealed that participant’s sex interacted with pre-interaction change in cortisol, suggesting that females exhibited less of an increase in cortisol relative to males; this association was not documented in the analyses focused on either partner or relationship uncertainty. We also observed a significant negative coefficient for self uncertainty, in both the combined and individual analyses, such that higher levels of self uncertainty corresponded with less of an increase in cortisol across the first three measurements. Likewise, partner uncertainty was negatively associated with the rate of cortisol change; this coefficient was significant in the analysis focused on partner uncertainty and approached significance in the combined model. Although relationship uncertainty was not significantly associated with the rate of cortisol change in the combined model, the individual analysis of relationship uncertainty indicated a negative and significant coefficient.

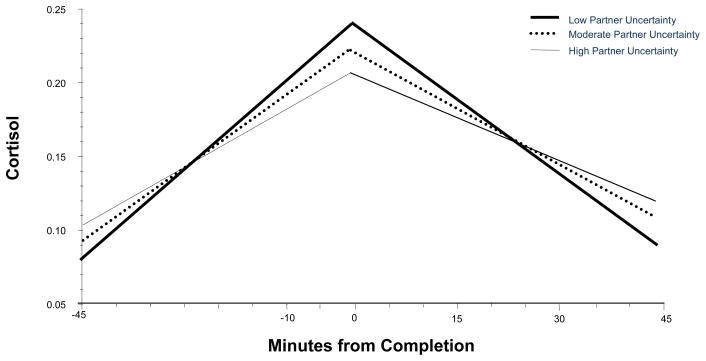

Results vary between the combined and individual analyses; however, they generally imply that relational uncertainty attenuated increases in cortisol across the first three measurements. Results for the equation predicting the post-interaction slope test H2, because they evaluate whether relational uncertainty was associated with the rate of cortisol recovery. In all four models, we observed a significant main effect of the post-interaction slope indicating that participants, on average, manifested decreases in cortisol across the four final measurements. We also observed a significant sex difference in all four analyses, such that decrease in cortisol during the recovery period was slower for females relative to males. Support effectiveness was not significantly associated with the cortisol measures of recovery in any of the analyses. With regard to H2, neither self (H2a) nor relationship uncertainty (H2c) was a significant predictor of the rate of cortisol change during the recovery period, in either the combined or individual analyses. Consistent with H2b, however, the coefficient for partner uncertainty was significant and positive in both the combined model and the separate analysis of partner uncertainty. The positive coefficient suggests that individuals experiencing greater partner uncertainty recovered from the stressor tasks more slowly than people with less partner uncertainty (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Changes in Cortisol over Time as a Function of Partner Uncertainty in Study 2

Discussion

We sought to extend previous theory and research, which has positioned relational uncertainty as a force that makes interactions with romantic partners difficult, by evaluating the associations between relational uncertainty and physiological stress responses to communicative events. Specifically, we examined how self, partner, and relationship uncertainty correspond with salivary cortisol reactivity to hurtful messages from a partner and how it impacts the effectiveness of emotional support messages after a stressful event, as measured by cortisol recovery. Across two studies, we tested the hypotheses predicting that relational uncertainty exacerbates cortisol reactivity (H1) and inhibits cortisol recovery (H2) associated with communication with a dating partner.

In the context of hurtful messages, we found that individuals who reported greater partner uncertainty experienced a significantly greater increase in salivary cortisol over the course of the study than individuals who were more certain about their partner’s feelings about the relationship. Contrary to our expectations, self uncertainty corresponded with a significant decrease in salivary cortisol in response to a partner’s hurtful messages, when controlling for relationship and partner uncertainty; however, the effect of self uncertainty on cortisol change was nonsignificant when self uncertainty was analyzed separately. In our second study, partner uncertainty was associated with significantly less recovery from a stressful episode following an interaction with the dating partner, as indicated by salivary cortisol. Study 2 also showed that self, partner, and relationship uncertainty tended to attenuate the cortisol response to the stress induction tasks. In other words, individuals who experienced relational uncertainty showed a smaller increase in cortisol after the stressful tasks.

On a general level, our findings address the basic theoretical assumption that relational uncertainty is a negative and stressful component in romantic relationships. Our results indicate that uncertainty about a partner’s involvement in the relationship can cause interactions with that partner to be either more stressful, in the case of hurtful interactions, or less stress relieving, in the case of supportive interactions. These findings align with early research on uncertainty and initial interactions, which focused on unknowns about a communication partner as the type of uncertainty most relevant to understanding communication challenges (for example Berger, 1975; Clatterbuck, 1979). More recent research also suggests that ambiguity about a partner’s involvement in the relationship leads people to attach more negative connotations to a romantic partner’s messages (Knobloch, Miller, Bond, et al., 2007). Thus, the patterns we observed could reflect either the tendency for partner uncertainty to generally exacerbate tension during interactions with that partner or a more elaborate process by which doubts about a partner lead to more negative message interpretations. Although further research is needed to clarify why partner uncertainty contributes to elevated salivary cortisol, these findings highlight how doubts about a partner’s commitment to the association can contribute to physiological stress.

Other findings ran counter to our assumption that relational uncertainty exacerbates the stress response. In particular, the results of Study 2 suggest that relational uncertainty may buffer individuals from physiological stress. On average, participants in Study 2 experienced an increase in cortisol associated with completing the stressful tasks; however, participants who reported relational uncertainty showed significantly lower cortisol increases during this period. Why might relational uncertainty correspond with lower cortisol reactivity to the tasks? To the extent that rate of cortisol change reflects experiences of threat, perhaps the threat imposed by performing poorly in competitive tasks while the partner watched, as well as anticipating a discussion of that performance with the partner, was greater for individuals who had relatively low relational uncertainty. In contrast, individuals who were relatively uncertain about their own feelings, their partner’s involvement in the relationship, or the relationship itself may have been less affected by the social-evaluative threat of the tasks. We wonder if people who have doubts about the relationship are less invested in the partner’s evaluation of their performance in these tasks, while individuals with less relational uncertainty are threatened by episodes that may alter that understanding. Perhaps people who have confidence in their perceptions of the association are reluctant to disclose their own failures and faults to partners because they don’t want to introduce ambivalence into an otherwise certain association. If substantiated in future work, this conclusion could have implications for understanding some people’s reluctance to seek social support from relationship partners.

When we examined the effects of self, partner and relationship uncertainty in combination, the results of Study 1 also indicated that people experiencing self uncertainty showed a decrease in cortisol in response to a partner’s hurtful messages. These findings resonate with previous research indicating that self uncertainty diverges from partner and relationship uncertainty in its associations with perceptions of relational turbulence (McLaren et al., in press) and the directness of communication about relationship problems (Theiss & Solomon, 2006b). In particular, those studies showed that people experiencing self uncertainty perceived their relationships as less turbulent and were more direct in confronting partners, whereas partner and relationship uncertainty accentuated perceptions of turbulence and inhibited direct communication about problems. Perhaps individuals who are uncertain about their own involvement in a relationship are less dependent on that association and, consequently, less vulnerable to their partner’s critical evaluations (Roloff & Cloven, 1990; Sprecher & Felmlee, 1997). By this logic, individuals who are working out their own commitment to a relationship may be insulated from the physiological consequences of negative relationship events.

On the other hand, we cannot rule out the possibility that the decreased cortisol in response to the hurtful interaction associated with self uncertainty is a sign of other underlying mechanisms not tested in this study. For example, a meta-analysis of studies that examined the relationship between depression and cortisol reactivity showed evidence that clinical depression is associated with blunted cortisol reactivity to stressors (Burke, Davis, Otte, & Mohr, 2005). Furthermore, in chronically stressed individuals, attenuated cortisol reactivity may be a sign of maladaptive alterations of the HPA axis (Fries, Hesse, Hellhammer, & Hellhammer, 2005). Interestingly, Knobloch and Knobloch-Fedders (2010) found that self, partner, and relationship uncertainty were positively correlated with females’ depressive symptoms, but not men’s. Although, in this study, we screened out participants who reported experiencing or being diagnosed with depression, these studies remind us that attenuated cortisol could be symptomatic of other underlying negative issues, rather than a sign that self uncertainty is buffering individuals from potential harmful effects of stress. To fully understand the positive and negative consequences of relational uncertainty on health outcomes, future research must examine how relational uncertainty and cortisol are impacted by a broader range of personal and situational variables.

Notably, the divergent association between self uncertainty and cortisol reactions to hurtful interactions was only documented when the variance associated with partner and relationship uncertainty was statistically accounted for within the multi-level model. When self uncertainty was analyzed individually, the association between self uncertainty and cortisol level was not significant. Unfortunately, neither analysis is conclusive. Because of the correlations among the relational uncertainty variables, the effects for self uncertainty in the combined model could be driven by spurious patterns in the limited variance remaining after the other relational uncertainty variables are covaried. On the other hand, positive associations among the relational uncertainty variables could be masking what is a true, divergent association between self uncertainty and cortisol reactions when the other relational uncertainty variables are not covaried. Given evidence discussed previously, which suggests that self uncertainty may give people some distance from negative consequences within a relationship, we are inclined to believe that self uncertainty may have unique effects, once it is disentangled from other questions and doubts about the relationship. We see developing theory and more definitive empirical tests of this possibility as a valuable direction for this program of research.

Finally, the associations between the facets of relational uncertainty and baseline cortisol in both studies provides preliminary insight into additional ways in which self, partner, and relationship uncertainty function differently to influence cortisol. In Study 1, relationship uncertainty was associated with greater baseline cortisol values, when the relational uncertainty variables were analyzed separately (an effect that was marginally significant in the combined model). The pattern of results found in Study 1 are the same as those found in hierarchical linear regression analyses of the Study 2 data, such that when relationship uncertainty is regressed onto baseline cortisol values, relationship uncertainty is positively associated with baseline cortisol, F(1, 102) = 5.10, R2 = .05, p < .05. Although speculative, we wonder if recruiting dating partners, per se, for a study induces a degree of stress for those individuals who are unsure about the status of their relationship. Moreover, to the extent that people experiencing relationship uncertainty begin research procedures in a more aroused physiological state than their more certain counterparts, they may manifest attenuated reactions to experimental stimuli. Consistent with this pattern, our findings suggest that relationship uncertainty may affect baseline cortisol more so than cortisol reactivity or recovery, whereas partner and self uncertainty impact changes in cortisol.