Abstract

Studies have shown racial disparities in neighborhood access to healthy food in the United States. We used a mixed methods approach employing geographic information systems, focus groups, and a survey to examine African Americans’ perceptions of the neighborhood nutrition environment in Pittsburgh. We found that African Americans perceive that supermarkets serving their community offer produce and meats of poorer quality than branches of the same supermarket serving White neighborhoods (p<0.001). Unofficial taxis or jitneys, on which many African Americans are reliant, provide access from only certain stores; people are therefore forced to patronize these stores even though they are perceived to be of poorer quality. Community-generated ideas to tackle the situation include ongoing monitoring of supermarkets serving the Black community. We conclude that stores should make every effort to be responsive to the perceptions and needs of their clients and provide an environment that enables healthy eating.

Keywords: community, social determinants of health, access to food, neighborhood, GIS

INTRODUCTION

Nutritious food—fruit and vegetable intake in particular—has been shown to be a protective factor against diabetes, heart disease, and some types of cancer (Joshipura et al., 2001, Key et al., 2004, Knowler et al., 2002, Liu et al., 1999, Ness and Powles, 1997). African Americans in Pittsburgh bear a disproportionate amount of the burden of mortality resulting from diabetes, heart disease, and cancer (Hunte, 2002, Robins, 2005) and nationwide, African American adult obesity rates are higher than those of White adults (Flegal et al., 2010). In order to affect dietary behavior, there must be access, both real and perceived, to grocery stores selling high-quality produce at affordable prices. In the United States (US), access to good, affordable produce is often a function of access to supermarkets, which, because of their economies of scale, make fresh produce available at lower prices than independently owned grocery stores. Recent evidence suggests that neighborhoods with access to large, chain supermarkets have a lower prevalence of obesity than those without such access (Black et al., 2009, Morland and Evenson, 2009). The eastern part of the city of Pittsburgh, where this study is based, is home to a large percentage of the African American population of Allegheny County, where Pittsburgh lies (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000). Our aim was to explore whether the African American community in these eastern neighborhoods of the city had access to a chain supermarket. If so, we wanted to understand people’s perceptions of the service and quality of food in their supermarkets, and whether these perceptions affected dietary behavior.

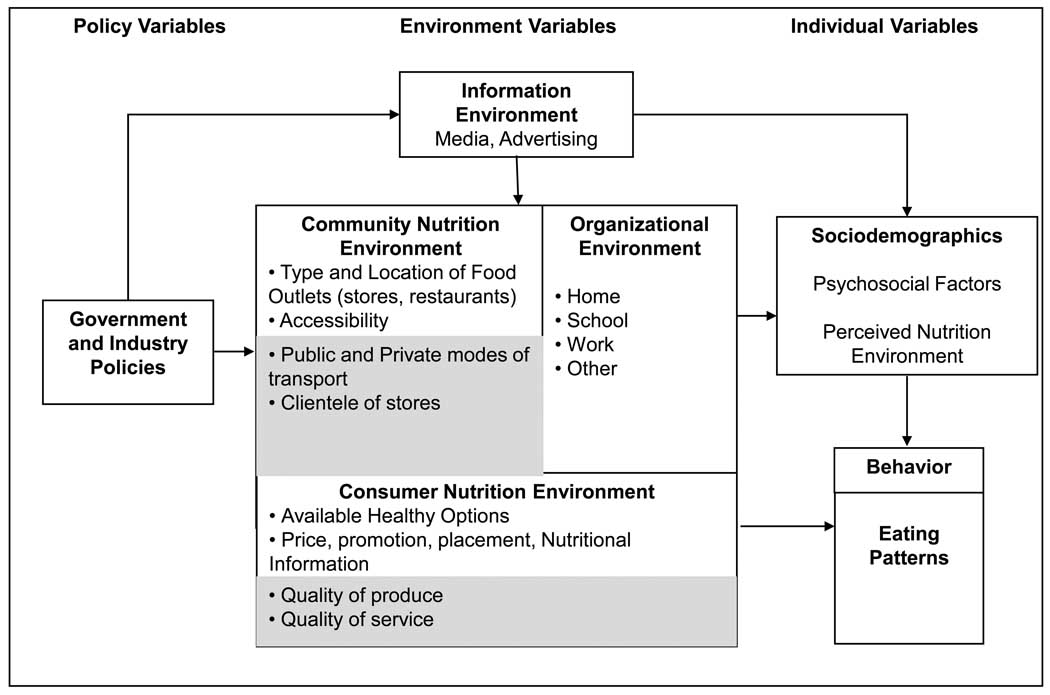

To conceptualize the neighborhood food resource environment, Glanz et al. (Glanz et al., 2005) put forth a model, which posits that multiple levels in the Social Ecological Model--policy, environmental variables, and individual-level variables--could affect dietary behavior. Of greatest relevance to this study are the concepts of the community nutrition environment and the consumer nutrition environment; the former represents the location of supermarkets and restaurants in the neighborhood, and people's access to them (in the form of public or private transportation). The latter represents people's experiences in stores, determined by the price, availability, and marketing of products.

Multiple studies have shown that African Americans have less access to supermarkets, and hence, a different community nutrition environment compared to Whites. Census tracts with less than 20% Black population had four times as many supermarkets as census tracts with greater than 80% African American population in four states studies (Morland et al., 2002b). In Baltimore, the availability of healthy foods, as determined by the Nutrition Environment Measures Survey--supermarkets (NEMS-S) (Glanz et al., 2007), was shown to be higher in predominantly White census tracts than in predominantly African American census tracts. Furthermore, supermarkets in Black census tracts had a lower healthy food availability index, a measure of the availability of healthy foods (determined using the NEMS-S), than those in White tracts (Franco et al., 2008). These studies suggest that African American neighborhoods have not only fewer supermarkets, but also poorer quality supermarkets and hence, less access to healthy food items than White neighborhoods. In a 2003 study in the city of Pittsburgh, most chain supermarkets lay in neighborhoods with less than 15% African American population (Borden et al., 2003); however, we know little about the quality of supermarkets serving White and Black neighborhoods in Pittsburgh.

Linking the presence of supermarkets to the diet of neighborhood residents has been more difficult. Morland et al. showed that fruit and vegetable intake by African Americans increased by 32% for every additional supermarket in their census tract (Morland et al., 2002a). In Baltimore, the healthy food availability index (HFAI) of a neighborhood correlated with lower fat intake, but not with whole grain or fruit consumption among residents (Franco et al., 2009). These studies did not, however, take into account neighborhood residents’ perceptions of the quality of stores and that of the food available in them, possibly an important determinant in people's dietary decisions. In fact, the lack of correlation between the HFAI and people's fruit intake in Baltimore (Franco et al., 2009) may be a direct result of the quality of fruit available in these stores, which was not assessed. Similarly, whereas no differences were found in the Brisbane food study between the price and availability of food in low- and high-income neighborhoods of Brisbane, Australia, there may indeed be differences in the real and perceived quality of produce available in these neighborhoods (Winkler et al., 2006).

The model presented by Glanz et al. does not explicitly include concepts of perceived food quality, or the quality of service in the store (Glanz et al., 2005). It has been shown, however, that women who shopped in supermarkets or specialty stores rated the quality and selection of produce higher and consumed more fruit and vegetable than those who shopped at independent grocery stores (Zenk et al., 2005). In Los Angeles, the number of people served by each grocery store was higher in African American neighborhoods than in neighboring White areas. Furthermore, fruits and vegetables were more damaged in grocery stores in African American neighborhoods than they were in White neighborhoods. The selection of produce was also significantly different in African American and White neighborhoods (Sloane et al., 2003).

We believe that studies need to take into account consumers' perceptions of the quality of food and service at stores in their neighborhoods when determining the neighborhood food environment. We explored African Americans' perceptions of their access to chain supermarkets in Pittsburgh. Using geographic information systems (GIS), a survey, and focus groups, we aimed to relate their perceptions to the location of supermarkets and their preferred store choices to their confidence in the ability to find and afford healthy, good quality food.

METHODS

This study included: 1) A description of the location of supermarkets in relation to neighborhoods using GIS; 2) A community-based survey of people's perceptions regarding their supermarkets; and 3) Two focus groups to gain an in-depth understanding of the reasons underlying people's choices with respect to supermarkets and dietary behavior. This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Geographic Information Systems Analyses

For the purposes of this study, we focus on chain supermarkets in Allegheny County, which includes national chain and value supermarkets as well as the dominant local chain supermarket. Addresses of supermarkets in the eastern neighborhoods of Pittsburgh and neighboring townships were obtained from the Allegheny County Health Department, and geocoded using ArcGIS (Environmental Systems Resource Institute, 2009). Population data as well as data regarding access to vehicles was obtained for census tracts in Allegheny County from the US Census Bureau (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000).

The Consumer Preference Survey

The Consumer Preference Survey was originally designed and used by the Community Health Councils, Inc. (CHC) in Los Angeles (Sloane et al., 2006). It was adapted, with permission from CHC, at the Center for Minority Health at the University of Pittsburgh, to suit the local situation in Pittsburgh. Specifically, we included demographic measures, including questions to gauge race, gender, level of education, and annual household income before taxes. The survey asked respondents their neighborhood of residence, zipcode, and name and address of “most frequently used grocery store.” It also queried the respondents on their mode and frequency of travel to shop and the number of people for whom they have purchased groceries. Rather than ask people whether they were unable to buy healthy food due to cost, as the original survey did, we framed questions that would allow us to gauge self-efficacy (a construct of the Social Cognitive theory (Bandura, 1977)) with respect to ability to afford and to find healthy food.

The survey was pilot tested in East Liberty, a neighborhood with 72.5% African American population, to test for appropriateness of wording and the length of the survey. It was then self-administered, either online or using a paper version, to a convenience sample of people who voted in the US presidential elections at the Kingsley Association in Larimer (87.9% African American) on November 4th 2008, as well as to participants of the Healthy Black Family Project (HBFP). At the time, the HBFP was a University of Pittsburgh health promotion and disease prevention program aimed at African American residents of the ‘Health Empowerment Zone,’ a collection of eastern neighborhoods in which the proportion of the population that is African American is greater than 60% (Thomas and Quinn, 2008). The Health Coaches at HBFP recruited participants for the survey. The survey was also offered in the neighborhood of Lincoln-Lemington Belmar (88.7% African American) through Lemington Community Services, a senior care center. Respondents completing the paper version of the survey had physical access and those completing the survey online had phone access to the first author in case they had questions; she received no questions in either case.

Survey analysis was carried out using SPSS (SPSS Inc., 2006). Bivariate analyses to address relationships with the outcomes (satisfaction with the quality and freshness of food, selection of produce, and selection of meat) were conducted using Fisher’s exact tests. Correlations between satisfaction level (very satisfied, satisfied, dissatisfied, or very dissatisfied) and confidence in ability to find or afford healthy food (extremely confident, very confident, somewhat confident, not very confident, or not confident) were conducted, and a Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient is reported. A p-value of <0.05 indicated a significant finding.

Annual household income (before taxes) was collected using a categorical scale. For each respondent, the mean of the income interval was divided by the number of people shopped for to arrive at an estimate of the income available per person in the household ($9999 was used for the category <$10,000; $50000 was used for the interval >=$50,000). Respondents were then categorized into two groups of roughly equal sizes: those earning $14,999/person and below as “low” income and those earning $16666.67 and higher as “high” income.

Focus Groups

Two focus groups were held. The first at the Kingsley Association involved four female participants of HBFP. The second focus group was held at the Vintage Inc. Senior Center in East Liberty and involved ten participants (9 females and 1 male). All participants were African American. The ideal size of focus groups varies based on the topic; we aimed to have no fewer than 4 people in each focus group and no more than 10 to maximize the possibility of in-depth discussion of people’s experiences in their grocery stores (Kitzinger, 1995, Krueger, 2009). Though four people is the smallest recommended size for focus groups, such small groups have been used in studies of neighborhood perception in the past (Yen et al., 2007). Expecting that both men and women engage in grocery shopping, we did not limit participation by gender. We have a mixture of same- and mixed-gender focus groups in this study; given the gender-neutral nature of the topic under study, we do not expect this to have introduced any bias. Both hour long focus groups were facilitated by the first author, with an independent note-taker. Participation in the focus groups was incentivized by raffling a $20 gift card to a co-operatively owned grocery store in the city.

The moderator welcomed participants, informed them about the voluntary nature of their participation in the study, and asked them to introduce themselves and the grocery store they shopped at most often. The discussion was then oriented towards the reasons for choosing the particular stores, the experience of shopping at those stores, what healthy food items they look for at the stores, and the ease or difficulty of finding these items.

Focus groups were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim and analyzed using inductive codes (Miles, 1994). Codes were generated to represent the major themes of the discussion in the first focus group. These codes were then applied to analyze the second focus group. One additional theme representing issues relevant to seniors was generated in focus group two. A codebook was maintained to facilitate reliability of coding. Coding Analysis Toolkit (CAT), an open source qualitative analysis application (http://cat.ucsur.pitt.edu/), was used to analyze the transcripts using the generated codes.

RESULTS

This paper will report descriptive results from the GIS study as well as survey and focus group results interspersed with each other, organized by substantive issues.

Demographics of Survey Respondents

As shown in Table 1, a majority of the 236 survey respondents were African American, and 28.6% were over the age of 65. Only 27.6% were male, and 37.9% reported having graduated from college. In addition, 69% of the 236 respondents took the survey on paper, with the rest taking it online.

Table 1.

Demographics and primary grocery store of survey respondents: n=236

| Characteristic | Number (%)* |

|---|---|

| Race | |

| African American | 191 (84.5) |

| White | 28 (12.4) |

| Asian American | 3 (1.3) |

| Other | 4 (1.8) |

| Age | |

| 18–35 | 42 (18.8) |

| 36–65 | 118 (52.7) |

| >65 | 64 (28.6) |

| Gender | |

| Females | 163 (72.4) |

| Male | 62 (27.6) |

| Education | |

| <High School | 19 (8.4) |

| High School Graduate | 53 (23.3) |

| Some college (1–3 years) | 60 (26.4) |

| College Graduate | 86 (37.9) |

| Decline to answer | 9 (4.0) |

| Annual Household Income | |

| <$10,000 | 26 (11.6) |

| $10,000–$19,999 | 36 (16.0) |

| $20,000–$29,999 | 35 (15.6) |

| $30,000–$49,999 | 42 (18.7) |

| >=$50,000 | 46 (20.4) |

| Decline to answer | 40 (17.8) |

| Annual Income/head | |

| Low =<$14,999 | 105 (57.7) |

| High >=$16,666 | 77 (42.3) |

| Primary Grocery store | |

| Store A | 45 (20.4) |

| Store B | 43 (19.5) |

| Store C | 19 (8.6) |

| Any other branch of the supermarket chain | 55 (24.9) |

| Other stores | 59 (26.6) |

Number of respondents for each characteristic differs due to varying levels of non-response

Eighteen percent of the respondents refused to answer the question asking about their annual income; the rest were distributed across the categorical income intervals in the survey. Income/head annually ranged from $1666.5 to $50,000. The average number of people respondents reported shopping for was 2.3. For a two-person household in the 48 contiguous states of the US, the federal poverty level threshold is $14,570 (Department of Health and Human Services, 2009). Thus, our low- and high-income categories are comparable to categorization by the federal poverty level in the US.

Where Respondents Shop

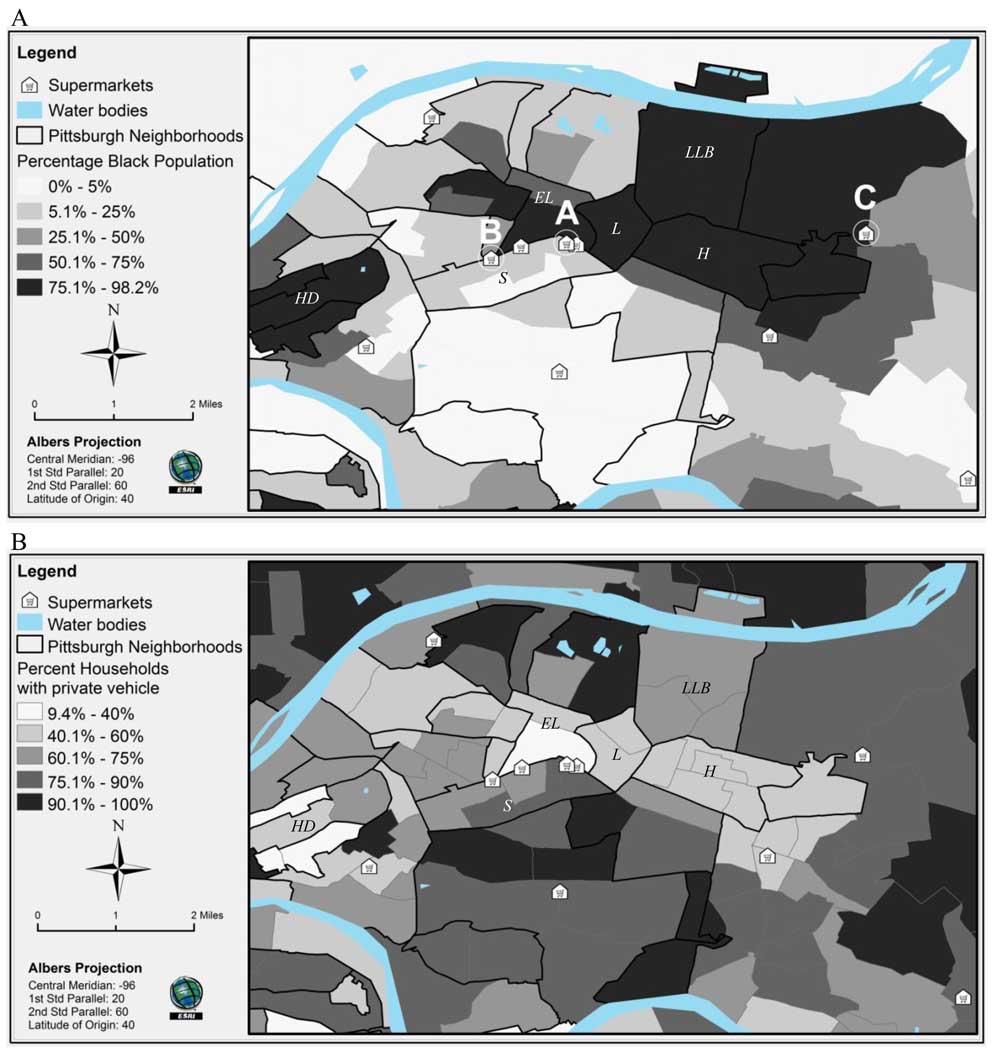

Respondents reported shopping for groceries in a range of stores. Only 11 respondents mentioned a co-operatively owned or specialty store as their primary grocery store. Most (95%) picked a supermarket as their primary grocery store; no one reported shopping primarily at a convenience store. Seventy-three percent of respondents mentioned a branch of the local supermarket chain as their primary grocery store (Table 1). Throughout the text, we refer to three branches of the dominant local supermarket chain, coded as A, B, and C. Please see Figure 1A for a map of the three branches. Store A is a branch on the border between a predominantly White neighborhood, Shadyside, and an African American neighborhood, East Liberty. Store B is a flagship branch of the supermarket chain, located less than a mile from Store A. Store C is an African American-owned franchise branch of the supermarket chain, located 3.7mi from StoreA.

Figure 1.

Supermarkets in the eastern neighborhoods of Pittsburgh. Neighborhoods mentioned in the text are labeled in italics: EL East Liberty, L Larimer, H Homewood, LLB Lincoln Lemington Belmar, S Shadyside, and HD Hill District. Stores picked most often as the primary grocery store are circled and labeled A, B, or C. Census tracts in Allegheny County were color-coded by percent Black population (A; see legend) or percent households with access to private vehicles (B; see legend).

Private transportation is not universally available in many African American neighborhoods. As seen in Figure 1B, neighborhoods such as Lincoln-Larimer-Belmar and Homewood—in which greater than 75% of the population is African American—have no supermarket within a 1 mile radius from the center of the neighborhood; these are also neighborhoods in which fewer than 75% of households have access to private vehicles. Compared to respondents of the survey from East Liberty or Larimer (n=66), those from Lincoln-Lemington-Belmar (n=23) were significantly poorer (p=0.013), twice as likely to travel to the grocery store by bus, and shopped significantly less frequently (Fisher's exact test; p=0.016). They were also more likely to shop at Store A than at Store B compared to respondents from East Liberty or Larimer (p=0.036; see below, and Figure 1A).

Stores Perceived to Cater to African Americans

As seen in Figure 1A, four supermarkets, including two national chain supermarkets, as well as stores A and B, which are both local chain supermarkets, lie within a 1 mile radius from each other on the border between Shadyside and East Liberty. African American participants in focus groups, however, perceived that only one of these four (Store A), and only 2 supermarkets in all (A & C in Figure 1A) served the Black community. Clientele and staff were reportedly all African American in store A in spite of the fact that the store lay in close proximity to a predominantly white neighborhood, Shadyside. The store is perceived to serve an exclusively African American customer base. One participant said this about Store A:

That used to be a mixed area. It is no longer that mixed. Most of the people in there---most of the customers are Black, most of the sales people are Black. And I just think it's a low priority. In terms of the care and the kind of staff they put in there.

A branch of the local supermarket chain in the northern Allegheny County borough of Fox Chapel is perceived to be the best of all branches. Suggesting that the quality of food sold at a store depends on the clientele, one focus group participant said:

Fox Chapel is Fox Chapel. The majority of the clientele is Caucasian, upper class. The people are nice, and not only their produce---their meats, cheeses, everything is so much better and fresher.

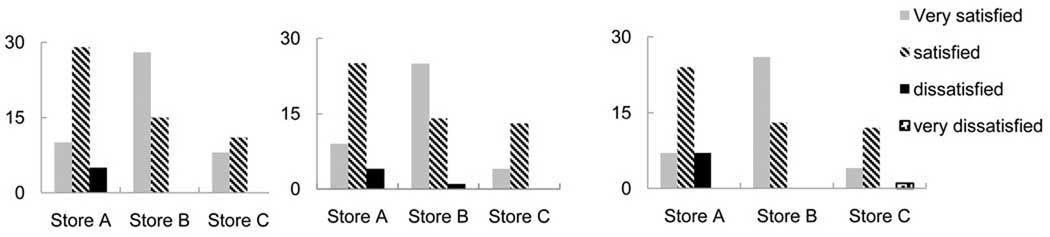

The Quality and Selection of Food in Stores

As seen in Figure 2, the proportion of people who are ‘very satisfied’ with the quality and freshness of food available in their primary grocery store was higher in Store B than either Store A or Store C. Similarly, satisfaction with the selection of produce (fruits/vegetables) was also lower in Stores A and C compared to B. Though most respondents picked either ‘very satisfied’ or ‘satisfied’ rather than ‘dissatisfied’ or ‘very dissatisfied’ to express their perception of the quality of food and the selection of produce, focus groups revealed a deeply dissatisfied clientele of stores A and C. Referring to Store A, one participant noted:

Well, in the produce, there's things like, however they pack it on the trucks or whatever, the first part of the truck's produce will probably go to certain areas, and by the time it gets to the back end, it may be a couple days, a week, then it gets to the other stores. I don't know if they do it systematically like that all the time, but you can kinda tell, because there's no way you'd be touching the fruit!

Figure 2.

Satisfaction level in the primary grocery store. A. Quality and freshness of food. n=106; Fisher’s exact test p<0.001. B. Selection of produce. n=95; Fisher’s exact test p<0.001. C. Selection of meat. n=94; Fisher’s exact test p<0.001

Currently, store A no longer sells fresh meat, forcing clients to buy only packaged meat. This may be one reason for the difference in satisfaction with the selection of meat between Stores A and B. As seen in Figure 2, the proportion of people ‘very satisfied’ with the selection of meat was significantly reduced at Stores A and C compared to that at Store B. Dissatisfaction with the quality of meat at Store A was a recurring theme in both focus groups. One participant put it thus:

They don't have the fresh meats---fresh poultry or fresh fish, where you can say I want that one, and that one. It's not like that, they're already packaged, sealed, with price, and a deadline for when it's supposed to be no longer sold, but you know, that may or may not be checked.

Concern was expressed about expiration dates on salads as well as meats at stores in the area: “Another thing is that you have to watch for expiration dates---their meats, I think they tie that over and put different stickers on them, and you've really got to be careful.”

Price of food

When asked if food was cheaper at Store A to make up for the lack in quality, one participant responded, “Same price. Low quality….food is directed to the area.” One respondent noted that she would like more in-store specials at Store A; these specials are reportedly offered at other branches of the local supermarket chain, but not at Store A. This is a theme that was discussed in one focus group:

The prices could be higher sometimes at [Store A] too, like you don't see….at some of the other [branches of the local chain supermarket] they have in-house manager sales. I have never seen that at [Store A].

One participant voiced her perception of the reason for this disparity between branches:

[At Store A,] they can't afford to lose any more profit. They're probably thinking they gotta get this much money if they can, from the people that do come into the store, whereas the other stores---they're getting a variety of communities, a variety of people coming in that are going to spend their money.

Quality of Service at Stores Catering to African Americans

Perception about the quality of service was gauged from open-ended comments in the survey and from focus groups. In response to a question about desired changes at the primary grocery store, respondents at both Stores A and B mentioned a desire for lower prices, but only respondents who shop primarily at Store A mentioned the need for more cashiers and more check-out clerks. There was a recurrent theme of bad service at Store A compared to other supermarkets in the area. One participant put it thus: “You could go within a radius of [Store A], and you can see the difference in the quality of the employees.” Furthermore, participants reported that the in-store manager was not responsive to their complaints, leading to a perception that stores in minority neighborhoods were not managed as well as stores in predominantly white communities:

They just want to make sure that they have these stores open, in these so-called communities. They don't care about the managers' attitude, and they don't care about how they run their store.

Why People Continue to Shop at Stores Perceived to be of Poorer Quality

As can be seen in Figure 1A, stores A and B are located near each other. They are also on many of the same bus routes. Hence, it becomes important to understand why people continue to shop at Store A given their perceptions that the quality and selection of food and meat at this store are inferior to that at Store B. Three themes emerged from the focus groups.

Need to support stores that cater to the Black community

A participant in one focus group voiced a need for stores in minority neighborhoods:

I stopped going there [to store A], but [my friend] had a very good point about---she said that she purposely goes there because she doesn't want them to close the store. Because they really are the only….you know they're one of the more accessible grocery stores for our community---for the black community.

The lived history of the community may give them reason to be apprehensive about Store A shutting down; a branch of the store that served a historic Black neighborhood, the Hill District, shut down in recent years, forcing Hill District residents to shop further away.

Jitneys are only available at some stores and not at others

Jitneys are unofficial taxis that are part of the historic landscape of Pittsburgh, providing an important service to Black communities where legal taxis are difficult to come by (May, 2004). A theme that arose in both focus groups was that of the availability of Jitneys at stores A and C, but not at Store B, effectively forcing people who did not have access to private transportation, to shop at stores in spite of perceptions of lower quality of food and service there. The importance of Jitneys in determining the choice of supermarket was voiced thus:

You only see that [Jitneys] at [Store C], and [Store A]. And they do that for the Black; people go there to do their large shopping, and they've got two carts. They can't afford to go to [Store B] because they can't get on the bus with that.

One participant reported that people from the Hill District without private transportation had to call for a Jitney at Store B, an added inconvenience, rather than find one waiting outside as was possible at Stores A and C:

They have to get a Jitney. And that's an extra expense. They have to go by bus and get a Jitney to bring their things back so that makes them have to spend more money. And at [Store B], they make them—they have to call for a Jitney to come, you know.

Pride in Black ownership of a franchise branch of the supermarket

A third theme that explains continued patronage of supermarkets perceived to offer low-quality food and service is support for African American ownership of the franchise branch (Store C) of the supermarket chain. Store C is owned by an African American; this is a major source of pride in the community, which wants her to be successful: “I really want to support her. I'm hoping that she's able to hold that store,” said one participant. A resident of Homewood, who perceives Store C to lie in her neighborhood, had this to say: “I live in Homewood, and we have been so many years without a grocery store, so finally [we] have one, it's owned by a black woman, and she keeps her store clean.” A complaint about Store C, while voiced in the first focus group, was qualified thus:

I mean it's not quite as bad [as Store A] but you can tell it's going to go that way. And I had to deal with the manager---I mean not the lady manager, but there was another manager---same attitude.

In spite of the lower level of satisfaction with the quality of produce and meat, and selection of produce available in store C reported in the survey (Figure 2), Black ownership of this franchise store is clearly a source of pride in the community and may serve as a moderating factor in the perceptions voiced about it.

The Impact of Perceptions on Self-efficacy

In order to eat a healthy diet, people need to both afford and find healthful foods in their stores. We measured people's confidence in their ability to engage in these two behaviors, and studied its correlation with their reported level of satisfaction with the quality and selection of produce and meat. As seen in Table 2, the more satisfied a person reported being with the quality of food, selection of produce, or the selection of meat, the more confident they were in their ability to find healthy food, irrespective of their household income.

Table 2.

Spearman correlation coefficients between satisfaction with quality and freshness of food and confidence in affording or finding healthy food in store; bold p<0.05

| Quality and Freshness | ||

|---|---|---|

| Low-income | High-income | |

| Affording healthy food | 0.174 | 0.381 |

| Finding healthy food | 0.301 | 0.516 |

A correlation between self-efficacy to afford healthy food and reported satisfaction with the quality and freshness of food (Spearman’s rho = 0.36; p<0.01) exists, but only for people who reported an annual income >$16,666.67 per person in the household. Among lower-income people (annual income per head in the household =<$14,999), there is no significant correlation between their level of satisfaction with the quality of food, and reported confidence in their ability to afford healthy food (see Table 2). This suggests that people's perception of the quality of food available to them is an important determinant of self-efficacy to afford healthy food, given a minimum level of income.

Community-generated Ideas to Tackle Issues

We asked focus group participants how their neighborhood nutrition environment might be improved.

The importance of having your voice heard

There was a recurring theme in both focus groups that complaints about Store A to the in-store manager were not acted on. One participant had this to say about the importance of complaining: “If people do not bring it to management's attention, they think everything is ok, or oh, that's the way they like to be treated.” Another participant said:

You'd have to go above management-you'd have to go to the corporate-and say, in these areas, in these stores, they need retraining, or new management or something like that. Because this talking to them-it's just like it falls on deaf ears.

One participant suggested that the clients of supermarkets could be involved in ongoing monitoring of the quality of food and services at the store:

I think every so often, they should do surveys, when people come in, they should pass out a survey. How was the service? Was the meat fresh? Was the vegetables fresh? What did you find wrong with the store? How were the attitudes? I think that would help too. And it would have to go to the corporate office. Not to the manager there, but to the corporate office. And let them handle it. Because that-I think that's the only way it would get solved.

This suggestion ties back to the original study conducted in Los Angeles; CHC, Inc. is implementing “Neighborhood Food Watch” (Community Health Councils Inc.) to involve the community in providing feedback to stores in an effort to encourage a dialog between clients and store managers about the needs and perceptions of shoppers.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that perceptions about the quality of food and service available to people are determined by their choice of supermarket. Only two of nine supermarkets in the eastern neighborhoods are perceived by African Americans to cater to their community. Respondents who shop at either of these two supermarkets rated their satisfaction with the quality and freshness of food, the selection of produce, and the selection of meat lower than did respondents who shopped at a different branch of the same supermarket. They also perceived the quality of service to be poorer at one of the two stores. In general, African Americans perceive that they are discounted, their voices not heard, and that the consumer nutrition environment available to them is poorer because of a lack of attention to stores that cater to a predominantly low-income, Black consumer base. This exploratory study provides findings that open up opportunities for future research to document the quality of the food environment in neighborhoods using objective measures such as the NEMS-S. The community-generated ideas suggest interventions that may improve the perceived quality and availability of healthy food to African Americans. We found that in Pittsburgh, access to stores is dependent on the availability of Jitneys, which reflect a legacy of discrimination against African Americans. Similar to our study, respondents in Adelaide, Australia, reported difficulty hauling grocery bags into and out of buses, and reported taking the bus to, but a taxi back from the grocery store. However, in Adelaide, access to taxis is subsidized by the government (Coveney and O'Dwyer, 2009). Subsidizing transportation costs (of either a legal taxi or a Jitney) from supermarkets is an approach that may be worth exploring in Pittsburgh.

Participants' ideas about tackling the issue of poor perceived quality of food in certain branches of the local supermarket chain included an ongoing monitoring program involving clients monitoring the quality of food and service. Ongoing monitoring of store A would entail participation by customers of this store—significantly poorer than customers of Store B and predominantly African American—in the management of this store. The NEMS-S (Glanz et al., 2007), a validated instrument designed and tested by Glanz et al. to measure the availability and quality of produce in stores, could be used, after adaptation to the local environment, to make objective measurements of the availability of food in supermarkets and other grocery stores serving the African American community in Pittsburgh. Its use in a community-based participatory manner to accurately measure quality of food available may be essential if the perceptions of the consumers themselves are to be factored in to understanding the environment accurately. If the in-store managers or corporate management of the chain were receptive to this idea, it has the potential to provide feedback to the store from shoppers, and over time, to improve efficiency and quality of food and service at the store. However, even in the absence of discernable improvement in the store itself, ongoing monitoring by this historically disadvantaged customer base could lead to capacity building and empowerment of the Black community. From the point of view of the social determinants of health, an acknowledgement by the community of their needs and voicing their perceptions on an ongoing basis could empower them to reassess their access to healthy food on a regular basis, and make the strides necessary to making sure that they have easy access to affordable, healthy food in their community. Community-based monitoring of ecology and health services is underway in multiple countries, with an explicit aim in each case, of empowering the community (Environment Canada, 2007, Management Sciences for Health and the United Nations Children's Fund, 1998, National Rural Health Mission, 2010).

Price has been shown to be a barrier to healthy eating in multiple studies (French, 2003, French et al., 1997, Steptoe et al., 1995). In our study, we found that self-efficacy to afford healthy food was increased when people (who earned >$16,666.67 per head annually) were satisfied with the quality of food available in their preferred grocery store. In low-income people, the perceived quality of food had no effect on self-efficacy to afford healthy food. The social cognitive theory suggests that self-efficacy is a pre-requisite to sustained behavior change (Bandura, 1977). We conclude that for low-income people, self-efficacy to afford healthy food can be increased through the presence of grocery stores that serve affordable healthy food in underserved neighborhoods, or by reducing the price of food in supermarkets. However, for people who earn more than $16,666.67 annually, improving the perceived quality and freshness of food and selection of produce available to them in their preferred supermarket should increase their self-efficacy to afford healthy food. In high- and low-income people alike, however, self-efficacy to find healthy food was high if people perceived the quality and freshness of food, and the selection of produce and meat to be of a high quality. Thus it is important that people perceive that their store makes available high-quality food if they are to be confident of their ability to find and buy healthy food.

In light of our results, we propose that the Glanz et al. model (Glanz et al., 2005) can be modified as shown in Figure 3; the construct of the community nutrition environment, which includes the location and type of stores, should also include the clientele or customer base of the store. Our results suggest that the perceived clientele of a store has an impact on the shopping behavior of residents, as well as on their perceptions of the quality of food available in the store. The dimension of access, which includes transportation, should reflect the availability of both public and private transportation, and both official and unofficial forms of transportation. The construct of the consumer nutrition environment should include the quality of food, and the quality of service, which impact people's shopping and dietary behaviors.

Figure 3.

Adapted from (Glanz et al., 2005); text on grey background is addition to the published model

We posit that the disparity in the perceived quality of the food environment between neighborhoods could be widespread, and should be examined along with the distribution of stores and availability of food in neighborhoods. This is relevant in cities both in the US and in other countries in which access to food is dependent on access to formal stores and restaurants. In Baltimore, US, the lack of correlation between the availability of produce and residents’ fruit-intake in neighborhoods (Franco et al., 2009) may be explained by differences in the quality of available produce. Similarly, in Brisbane, Australia, the lack of difference in the availability and variety of produce in neighborhoods by socioeconomic characteristics (Winkler et al., 2006) does not preclude a difference in the real or perceived quality of produce available to residents there. We suggest that it is important to explore people’s perceived access to high quality, healthy food in order to understand and affect dietary behavior.

This study has several limitations. Our survey was administered to a convenience sample which limits our ability to generalize our findings to the African American population at large in these neighborhoods. However, we do have representation from across the age, education, and income ranges expected in these neighborhoods (Pittsburgh Department of City Planning, 2000), increasing our confidence in the ability of the data to contribute valuable information about the perceptions and needs of residents in these areas. The survey was offered in two forms—either online or on paper. We expected that making a computer terminal with the survey available at the Kingsley center would encourage people to take the online version. We made the paper version available for those who might be uncomfortable using a computer. When people had access to the online and paper versions, they overwhelmingly chose the paper version (observed at the Kingsley center). We conclude that surveys in a community setting may be best offered on paper, and should probably also be made available with the explicit option of interview administration to enable lower literate people to take the survey. We acknowledge that having the survey available in two forms introduced the potential for bias; however, we believe it enabled older people and those unfamiliar with computers to take the survey.

We have focused only on a subset of neighborhoods in Pittsburgh and adjoining Boroughs in Allegheny County, based on the Health Empowerment Zone (Robins, 2005, Thomas and Quinn, 2008). The study gives us valuable information about the perceptions of African Americans in these areas, but does not allow us to draw conclusions about supermarkets in other areas of the city/county. Our study of the community nutrition environment focused on supermarkets, and did not explore the distribution of convenience stores or fast-food outlets, both important aspects of the nutrition environment available to community residents. However, given our finding that 95% of our survey respondents shop primarily in a supermarket, and none reported shopping primarily in a convenience store, we hypothesize that compared to African American neighborhoods that may be farther away from supermarkets in many other US cities, African American neighborhoods in Pittsburgh may be less reliant on convenience stores.

CONCLUSIONS

We conclude from this study, that the community and consumer food environment have impacts on the perception of individuals regarding the healthy food available to them, and impact their behavioral choices. Eating a healthy diet is essential in preventing multiple chronic diseases. This study demonstrates that customers of specific stores in the eastern neighborhoods of Pittsburgh perceive a poor quality of food and service directed at the Black community. We suggest that stores should pro-actively engage their customers in ongoing monitoring in order to understand their concerns and needs. This could lead to the empowerment of the community along with improvement in the quality of healthy food available in the store. Ultimately, this should lead to better access to healthy food in disadvantaged communities and a reduction in the rate of chronic disease and obesity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the health coaches, especially Felicia Savage, as well as Tom Sturgill, and Arnold Perry for their help with recruitment of participants for this study. We are grateful to CHC, Inc. for sharing their survey instrument with us. This study was funded through the Research Center of Excellence on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIH-NCMHD: 2P60MD000207-08; PI, Thomas).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black JL, Macinko J, Dixon LB, Fryer GE., Jr Neighborhoods and obesity in New York City. Health Place. 2009;16:489–499. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borden M, Niemeyer M, Dalton E, Shucker C, Ehrlich S, Velezmoro AJ, Flores M, Walsh L, Heberlein E. Food Availability in Allegheny County, PA Systems Synthesis Project Summer 2003. Pittsburgh: The H. John Heinz III School of Public Policy and Management, Carnegie Mellon University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Community Health Councils Inc. Los Angeles: Neighborhood Food Watch; [Google Scholar]

- Coveney J, O'dwyer LA. Effects of mobility and location on food access. Health Place. 2009;15:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services. The 2009 Poverty Guidelines for the 48 Contiguous States and the District of Columbia. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Environment Canada. Community based monitoring. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Systems Resource Institute. ArcMap 9.2. Redlands, California: ESRI; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco M, Diez Roux AV, Glass TA, Caballero B, Brancati FL. Neighborhood characteristics and availability of healthy foods in Baltimore. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:561–567. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco M, Diez-Roux AV, Nettleton JA, Lazo M, Brancati F, Caballero B, Glass T, Moore LV. Availability of healthy foods and dietary patterns: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:897–904. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French SA, Story M, Jeffery RW, Snyder P, Eisenberg M, Sidebottom A, Murray D. Pricing strategy to promote fruit and vegetable purchase in high school cafeterias. J Am Diet Assoc. 1997;97:1008–1010. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(97)00242-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French SA. Pricing effects on food choices. J Nutr. 2003;133:841S–843S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.3.841S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Frank LD. Healthy nutrition environments: concepts and measures. Am J Health Promot. 2005;19:330–333. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-19.5.330. ii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Frank LD. Nutrition Environment Measures Survey in stores (NEMS-S): development and evaluation. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunte H, Bangs R, Thompson D. Status of African Americans in Allegheny County: A Black Paper for the Urban League of Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Joshipura KJ, Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Rimm EB, Speizer FE, Colditz G, Ascherio A, Rosner B, Spiegelman D, Willett WC. The effect of fruit and vegetable intake on risk for coronary heart disease. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:1106–1114. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-12-200106190-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Key TJ, Schatzkin A, Willett WC, Allen NE, Spencer EA, Travis RC. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of cancer. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7:187–200. doi: 10.1079/phn2003588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger J. Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. BMJ. 1995;311:299–302. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. SAGE; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Latham J, Moffat T. Determinants of variation in food cost and availability in two socioeconomically contrasting neighbourhoods of Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. Health Place. 2007;13:273–287. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Stampfer MJ, Hu FB, Giovannucci E, Rimm E, Manson JE, Hennekens CH, Willett WC. Whole-grain consumption and risk of coronary heart disease: results from the Nurses' Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:412–419. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.3.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Management Sciences for Health and the United Nations Children's Fund. Community-Based Monitoring. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- May G. Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Pittsburgh: 2004. Jitneys remain in driver's seat. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A. The contextual effect of the local food environment on residents' diets: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am J Public Health. 2002a;92:1761–1767. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A, Poole C. Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places. Am J Prev Med. 2002b;22:23–29. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morland KB, Evenson KR. Obesity prevalence and the local food environment. Health Place. 2009;15:491–495. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Rural Health Mission, G. O. I. Community based monitoring of health services under NRHM. 2010

- Ness AR, Powles JW. Fruit and vegetables, and cardiovascular disease: a review. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:1–13. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittsburgh Department of City Planning. Census: Pittsburgh A comparative digest of Census data for Pittsburgh's neighborhoods. Pittsburgh, PA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Robins AG. Surveillance of Selected Chronic Diseases: Benchmarks for the Healthy Black Family Project. Allegheny County Health Department; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sloane D, Nascimento L, Flynn G, Lewis L, Guinyard JJ, Galloway-Gilliam L, Diamant A, Yancey AK. Assessing resource environments to target prevention interventions in community chronic disease control. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006;17:146–158. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloane DC, Diamant AL, Lewis LB, Yancey AK, Flynn G, Nascimento LM, Mccarthy WJ, Guinyard JJ, Cousineau MR. Improving the nutritional resource environment for healthy living through community-based participatory research. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:568–575. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21022.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoyer-Tomic KE, Spence JC, Raine KD, Amrhein C, Cameron N, Yasenovskiy V, Cutumisu N, Hemphill E, Healy J. The association between neighborhood socioeconomic status and exposure to supermarkets and fast food outlets. Health Place. 2008;14:740–754. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spss Inc. SPSS 15.0 for Windows. Chicago IL: SPSS Inc.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Pollard TM, Wardle J. Development of a measure of the motives underlying the selection of food: the food choice questionnaire. Appetite. 1995;25:267–284. doi: 10.1006/appe.1995.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SB, Quinn SC. Poverty and elimination of urban health disparities: challenge and opportunity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1136:111–125. doi: 10.1196/annals.1425.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Census 2000 Summary File 3. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Winkler E, Turrell G, Patterson C. Does living in a disadvantaged area entail limited opportunities to purchase fresh fruit and vegetables in terms of price, availability, and variety? Findings from the Brisbane Food Study. Health Place. 2006;12:741–748. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen IH, Scherzer T, Cubbin C, Gonzalez A, Winkleby MA. Women's perceptions of neighborhood resources and hazards related to diet, physical activity, and smoking: focus group results from economically distinct neighborhoods in a mid-sized U.S. city. Am J Health Promot. 2007;22:98–106. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-22.2.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenk SN, Schulz AJ, Israel BA, James SA, Bao S, Wilson ML. Neighborhood racial composition, neighborhood poverty, and the spatial accessibility of supermarkets in metropolitan Detroit. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:660–667. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]