Abstract

Mechanistic investigations of a MeOH-induced kinetic epoxide-opening spirocyclization of glycal epoxides have revealed dramatic, specific roles for simple solvents in hydrogen-bonding catalysis of this reaction to form spiroketal products stereoselectively with inversion of configuration at the anomeric carbon. A series of electronically-tuned C1-aryl glycal epoxides was used to study the mechanism of this reaction based on differential reaction rates and inherent preferences for SN2 versus SN1 reaction manifolds. Hammett analysis of reaction kinetics with these substrates is consistent with an SN2 or SN2-like mechanism (ρ = −1.3 vs. ρ = −5.1 for corresponding SN1 reactions of these substrates). Notably, the spirocyclization reaction is second-order dependent on MeOH and the glycal ring oxygen is required for second-order MeOH catalysis. However, acetone cosolvent is a first-order inhibitor of the reaction. A transition state consistent with the experimental data is proposed in which one equivalent of MeOH activates the epoxide electrophile via a hydrogen bond while a second equivalent of MeOH chelates the sidechain nucleophile and glycal ring oxygen. A paradoxical previous observation that decreased MeOH concentration leads to increased competing intermolecular methyl glycoside formation is resolved by the finding that this side reaction is only first-order dependent on MeOH. This study highlights the unusual abilities of simple solvents to act as hydrogen-bonding catalysts and inhibitors in epoxide-opening reactions, providing both stereoselectivity and discrimination between competing reaction manifolds. This spirocyclization reaction provides efficient, stereocontrolled access to spiroketals that are key structural motifs in natural products.

INTRODUCTION

Catalysts that exploit hydrogen bonds to accelerate organic reactions are powerful complements to Lewis acids. Mild and environmentally benign, Brønsted acids are often effective catalysts because their weak interactions with substrates afford low product inhibition and high turnover.1 Indeed, the seminal disclosure by Wassermann on the acceleration of Diels–Alder cycloadditions by phenol and substituted acetic acids preceded the first report of Lewis acid catalysis of this reaction by nearly two decades.2 However, hydrogen-bonding catalysis did not recapture scientific interest until the mid-1980s, when Hine demonstrated the power of cooperative hydrogen-bonding interactions in the epoxide opening of phenyl glycidyl ether, in which 1,8-biphenylene diol provided a 600-fold rate increase compared to a monoprotic acid of the same strength.3 Related bidentate catalysis by proximal tyrosine residues has also been observed in epoxide hydrolase enzymes.4 These studies set the stage for the more recent development of other epoxide-opening reactions that are catalyzed by hydrogen-bonding interactions with hydroxyl functionalities.

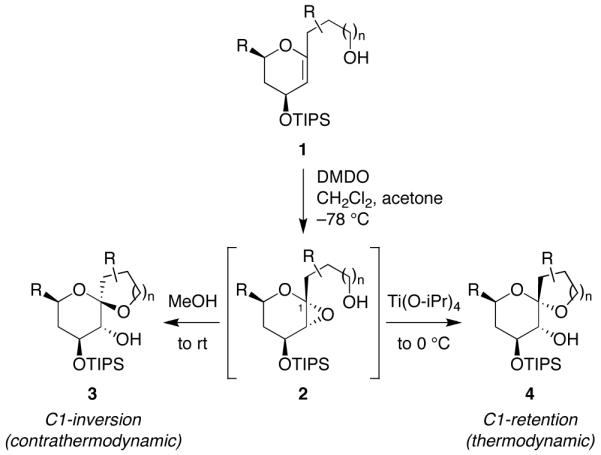

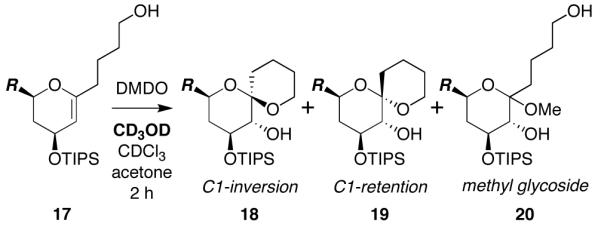

We have previously reported a novel MeOH-induced kinetic epoxide-opening spirocyclization of glycal epoxides to form spiroketal products stereoselectively with inversion of configuration at the anomeric carbon (Figure 1).5,6 A complementary Ti(Oi-Pr)4-catalyzed spirocyclization reaction provides the C1-epimeric spiroketals with retention of configuration at the anomeric carbon.7 These reactions afford stereocontrolled access to spiroketals, independent of thermodynamic considerations that govern classical approaches to these structures.8

Figure 1.

Stereoselective spirocyclization of glycal epoxides (2) with inversion (3) or retention (4) of configuration at the anomeric carbon. DMDO = dimethyldioxirane; TIPS = triisopropylsilyl.

We have proposed that the MeOH-induced epoxide-opening spirocyclization proceeds via hydrogen-bonding catalysis.5 This hypothesis was based on several observations: (1) Polar aprotic solvents do not induce spirocyclization, suggesting that the reaction is not driven simply by solvent polarity effects. (2) A methyl glycoside side product, which results from competing intermolecular epoxide opening with MeOH, is not converted to the spiroketal product upon reexposure to reaction conditions, eliminating it as a potential intermediate in mechanisms involving nucleophilic catalysis by MeOH. (3) Subjection of a thermodynamically-favored retention product (4) to the reaction conditions does not afford the inversion product (3), indicating that the MeOH-induced spirocyclization is under kinetic control.5

Subsequently, related epoxide-opening reactions have been reported to be catalyzed by water, methanol, and other simple alcohols, and similarly proposed to proceed via hydrogen-bonding catalysis. Jamison and coworkers have reported second-order catalysis by water in their landmark studies of regioselective epoxide-opening cascades to form ladder polyethers.9 Williams and coworkers have provided computational support for hydrogen-bonding catalysis at the distal epoxide in their intriguing work on spirodiepoxide-opening reactions.10 To date, however, the role of hydrogen-bonding catalysis in epoxide-opening spirocyclizations of glycal epoxides, and the critical and distinctive impact upon stereoselectivity in this reaction, has not been studied in detail. Outstanding questions also remain regarding the possible role of acetone, a residual cosolvent from the initial glycal epoxidation with dimethyldioxirane, and the paradoxical observation that decreased MeOH concentrations lead to increased competing intermolecular methyl glycoside formation.

Herein, we report our detailed mechanistic studies of this reaction using kinetic analyses of a series of electronically-tuned glycal epoxide substrates. Experimental evidence is provided for stereoselective formation of inversion products 3 via an SN2 or SN2-like reaction manifold, rather than an alternative SN1 mechanism. We have also investigated the temperature dependence of the reaction, determined the kinetic order of MeOH in the transition state, identified the acetone cosolvent as an inhibitor of the reaction, and unraveled the paradox regarding competing intermolecular methyl glycoside formation. A transition state structure is proposed based on these experimental results.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

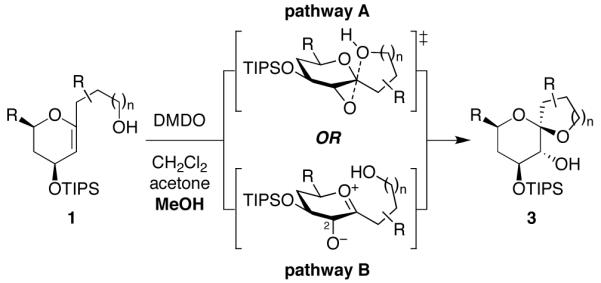

Our glycal epoxide substrates are structurally and electronically distinct from the 1,2-dialkyl epoxide and spirodiepoxide substrates studied previously by the Jamison and Williams groups.9,10 In particular, the observed stereoselectivity for inversion of configuration at the anomeric carbon may be attributed to either of two possible reaction mechanisms (Figure 2). An SN2 reaction manifold (pathway A) would require sufficient hydrogen-bonding activation of the epoxide electrophile to induce nucleophilic substitution by the sidechain hydroxyl group without formation of a discrete oxocarbenium intermediate, which might lead to reduced stereoselectivity. Alternatively, an SN1 mechanism (pathway B) might still afford high stereoselectivity if the C2-alkoxide could sterically and/or electronically block one face of the oxocarbenium ion-pair intermediate. While there is a wealth of literature devoted to describing the influence of nucleophiles, electrophiles, and reaction conditions in promoting SN1 and SN2 manifolds in glycosylation11,12 and solvolysis12,13 reactions, at benzylic positions14,15 and at acetals,16 the majority of these studies have involved intermolecular reactions of relatively simple substrates. Moreover, attempts to distinguish between SN1 and SN2 manifolds are complicated by the fact that some of the reactions cited above fall into a gray area along the SN1–SN2 continuum and, in some cases, are described as having concurrent, competing reaction manifolds.15,17,18 We envisioned that detailed kinetic studies of a series of electronically-tuned glycal epoxide substrates would allow us to distinguish between these two pathways in this intramolecular reaction of these complex substrates.

Figure 2.

Possible SN2 and SN1 mechanisms for MeOH-induced epoxide-opening spirocyclization of glycal epoxides with inversion of configuration at the anomeric carbon.

Selection of Reaction Probes.

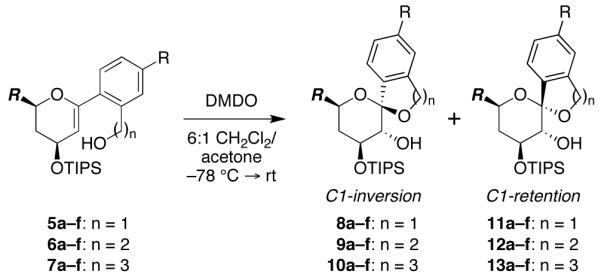

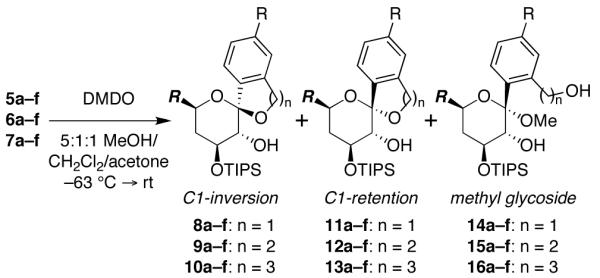

We recently developed a systematic approach to the synthesis of benzannulated spiroketals from C1-aryl glycal substrates.6 To probe the mechanism of the epoxide-opening spirocyclization, we synthesized a series of these glycal substrates in which the electronic character of the anomeric carbon was modulated using various C1-aryl substituents (Table 1, 5–7). These substrates were converted to the corresponding glycal epoxides in situ and exposed to spontaneous thermal or MeOH-induced spirocyclization conditions.

Table 1. Spontaneous Thermal Spirocyclizations of Substituted C1-Aryl Glycal Epoxides.a.

| ratio of inversion (8–10) to retention (11–13) products | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R = OMe (a) | Me (b) | H (c) | Cl (d) | CF3 (e) | NO2 (f) | |

| 8:11 (n = 1) | <2:98 | 13:87 | 31:69 | 32:68 | 27:73 | 67:33 |

| 9:12 (n = 2) | <2:98 | <2:98 | 9:91 | 19:81 | 43:57 | 44:56 |

| 10:13 (n = 3) | <2:98 | <2:98 | <2:98 | <2:98 | <2:98 | 18:82 |

Glycal epoxides generated in situ from glycal precursors with DMDO (−78 °C, 10 min), then allowed to warm to rt. Reactions proceeded in quantitative yields and product ratios were determined by 1H-NMR analysis.

R = CH2CH2OTBDPS.

Diastereomeric product ratios resulting from spontaneous thermal spirocyclizations (−78°C → rt) were first determined to assess the electronic influence of the various aryl substituents (Table 1). While most of these reactions favored spirocyclization with retention of configuration at the anomeric carbon to form thermodynamically-favored (bisanomeric) spiroketals (11–13), increasing formation of the contrathermodynamic (mono-anomeric) inversion products (8–10) was observed for more electron-deficient substituents (e.g., 5a–7a vs. 5f–7f). These results are as expected for formation of retention products via a presumed SN1 mechanism, which is favored by electron-donating substituents that stabilize the discrete oxocarbenium intermediate and disfavored by electron-withdrawing substituents that destabilize this intermediate.19 Interestingly, larger ring systems showed enhanced preferences for spirocyclization with retention of configuration (5 vs. 6 vs. 7), suggesting that the corresponding inversion products are formed, at least in part, via an SN2 mechanism, which becomes less competitive with the SN1 process as the rate of cyclization decreases, since the rate-limiting step in the latter reaction is oxocarbenium formation rather than cyclization.

Next, we investigated the corresponding MeOH-induced epoxide-opening spirocyclizations (Table 2). As expected, MeOH provided increased selectivity for inversion of configuration compared to the spontaneous thermal spirocyclizations (cf. Table 1), although inherent substrate biases could still be observed (e.g., 5a–7a vs. 5f–7f). As the methyl glycosides have previously been eliminated as intermediates in these reactions5 (e.g., double inversion, net retention), the retention products must form via an SN1 mechanism. Consistent with this mechanism, electron-donating substituents again trended toward increased levels of retention products when considered across the entire substrate panel, presumably by stabilizing the oxocarbenium intermediate, while electron-withdrawing substituents conversely trended toward enhanced selectivity for inversion of configuration by destabilizing this intermediate. Larger ring systems likewise exhibited enhanced preferences for spirocyclization with retention of configuration (5 vs. 6 vs. 7), as well as increased formation of methyl glycoside side products (16) that result from competing intermolecular epoxide opening by MeOH, also with retention of configuration at the anomeric carbon. This again suggests that the inversion products are formed preferentially via an SN2 mechanism that becomes less competitive with alternative SN1 processes as the rate of cyclization decreases. Notably, the combination of electron-withdrawing substituents and MeOH-induced spirocyclization allowed selective access to 7-membered ring products with inversion of configuration (10d–f) for the first time via this approach.6

Table 2. MeOH-Induced Spirocyclizations of Substituted C1-Aryl Glycal Epoxides.a.

| ratio of inversion (8–10) to retention (11–13) products | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R = OMe (a) | Me (b) | H (c) | Cl (d) | CF3 (e) | NO2 (f) | |

| 8:11 (n = 1) | 88:12 | 95:5 | >98:2 | >98:2 | >98:2 | >98:2 |

| 9:12 (n = 2) | 5:95 | 37:63 | 47:53 | 55:45 | 68:32 | 63:37 |

| 10:13 (n = 3) | <2:51b | <2:46b | <2:38b | 18:44b | 81:12b | 93:7 |

Glycal epoxides generated in situ from glycal precursors with DMDO (−78 °C, 10 min), stirred at −63 °C for 2 h, then allowed to warm to rt. Reactions proceeded in quantitative yields and product ratios were determined by 1H-NMR analysis.

Remainder methyl glycoside 16.

R = CH2CH2OTBDPS.

Based on these results, we surmised that this panel of C1-aryl glycal substrates possessed sufficient electronic variability to influence product distribution and to allow us to probe the mechanism of the MeOH-induced epoxide-opening spirocyclization reaction through detailed kinetic studies.

Temperature Dependence of MeOH-Catalyzed Epoxide-Opening Spirocyclization.

Next, in preparation for kinetic studies using low-temperature NMR, we sought to determine the temperature at which epoxide-opening spirocyclization occurs. To provide a direct comparison to our earlier mechanistic studies with the aliphatic glycal 17,5 we began by investigating the spirocyclization of this substrate (Table 3). The glycal was dissolved in CD3OD (17.8 M solvent concentration) and cooled to −78 °C, followed by addition of DMDO in acetone to generate the corresponding glycal epoxide in situ. The sample was then transferred to a precooled NMR probe, by which time the glycal had been converted completely to the corresponding glycal epoxide (<3 min). As observed by low-temperature NMR, the glycal epoxide intermediate was stable at −63 °C over a 2 h time frame (entry 1). Conversion to products within 2 h was observed beginning at −40 °C (not shown), with efficient formation of spiroketal 18 and methyl glycoside 20 occurring at −35 °C (entry 2).20

Table 3. Optimal Temperatures for Stereoselective Epoxide-Opening Spirocyclization of Glycal Epoxide Substrates.a.

| entry | substratea | T (°C) | CD3OD (M) | inversion (18, 8-10) |

retention (19, 11-13) |

glycoside (20, 14-16) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 17 | −63 | 17.8b | nr | ||

| 2 | 17 | −35 | 17.8 | 93 | 0 | 7 |

|

| ||||||

| 3 | 5c (R = H) | −35 | 17.8 | >98 | <2 | 0 |

| 4 | 5c (R = H) | −35 | 11.9c | >98 | <2 | 0 |

| 5 | 5c (R = H) | −35 | 0 | nr | ||

|

| ||||||

| 6 | 6c (R = H) | −20 | 17.8 | 70 | 30 | 0 |

| 7 | 7c (R = H) | 0 | 17.8 | 0 | 41 | 59 |

Glycal epoxides generated in situ from glycal precursors with DMDO (−78 °C, 10 min), then warmed to the indicated temperature in the NMR probe.

6:1:1.3 CD3OD/CDCl3/acetone.

4:3:1.3 CD3OD/CDCl3/acetone.

R = CH2CH2OTBDPS; nr = no reaction.

In our initial report, we noted that decreased MeOH concentration led to marked decreases in both stereoselectivity (18 vs. 19) and chemoselectivity (18, 19 vs. 20).5 However, consistent with the enhanced selectivities observed with five-membered ring systems above (Tables 1 and 2), stereo- and chemoselective spirocyclization of the glycal epoxide derived from C1-aryl glycal 5c could be achieved equally effectively at both the original concentration (17.8 M CD3OD) and a somewhat lower concentration (11.9 M CD3OD) (entries 3 and 4). Importantly, the glycal epoxide was unreactive at −35 °C in the absence of CD3OD (entry 5). These findings were valuable as they allowed the convenient design of experiments in which the concentrations of all three solvents could be varied to assess their influences upon reaction outcome and in which the slower reaction rate at 11.9 M CD3OD facilitated kinetic studies by low-temperature NMR (vide infra).

The corresponding six- and seven-membered ring systems (6c, 7c) only began to spirocyclize at higher temperatures and did so with decreased stereo- and chemoselectivity (entries 6 and 7). Consistent with our mechanistic hypotheses above, we reasoned that, for these larger rings, epoxide-opening spirocyclization with inversion of configuration via an SN2 manifold requires temperatures at which SN1 reactions via oxocarbenium intermediates become competitive or even dominant.

Thus, having identified appropriate temperatures for NMR analysis of the epoxide-opening spirocyclization reactions, we were poised to carry out detailed kinetic studies of these reactions.

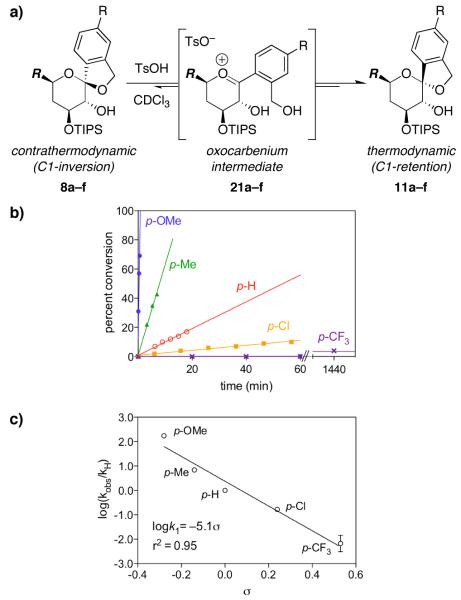

Hammett Analysis of Acid-Catalyzed Spiroketal Epimerization via an SN1 Mechanism.

Substrates having electron-withdrawing C1-aryl substituents exhibit increased preferences for epoxide-opening spirocyclization with inversion of configuration (Tables 1 and 2). Because oxocarbenium formation should be strongly disfavored in these substrates, we postulated that the inversion products are formed via an SN2 pathway rather than an SN1 pathway (Figure 2). To explore this idea further, we first characterized reactions known to proceed by an SN1 mechanism to serve as a benchmark against which to compare our proposed SN2 MeOH-catalyzed epoxide-opening spirocyclization.15,18

Thus, contrathermodynamic (inversion) spiroketals 8a–f were treated with TsOH (10 mol% in CDCl3) at rt to induce epimerization to the corresponding thermodynamic (retention) spiroketals 11a–f via oxocarbenium intermediates 21a–f (Figure 3a). The rate of conversion via this SN1 mechanism was measured by NMR. Substrates having electron-donating C1-aryl substituents that stabilize the requisite oxocarbenium intermediate were expected to exhibit faster reaction rates, while substrates having electron-withdrawing substituents were expected to display slower rates. Accordingly, the p-methoxy-substituted spiroketal 8a reacted completely within <2.5 min (Figure 3b), while the p-nitro-substituted spiroketal 8f showed no conversion over 72 h. Spiroketals 8b–e, bearing substituents with intermediate electronic properties, displayed intermediate rates.

Figure 3.

Hammett analysis of acid-catalyzed spiroketal epimerization via an SN1 mechanism. a) SN1 mechanism for acid-catalyzed epimerization of contrathermodynamic (inversion) spiroketals 8a–f to thermodynamic (retention) spiroketals 11a–f. R = CH2CH2OTBDPS. b) Rates of conversion with 10 mol% TsOH in CDCl3 at rt. The p-nitro-substituted substrate 8f does not react within 72 h under these conditions. Pseudo-first-order rate differences among the six substrates 8a–f illustrate the electronic requirements for the formation of oxocarbenium intermediates 21a–f. Representative data from one of two replicate experiments shown. c) Hammett plot exhibits a linear correlation for the electronically varied substrates 8a–e with a steep negative slope indicative of an SN1 transition state (ρ = −5.1).

Rate constants were determined using the initial rates for these SN1 processes, and the logarithms of these observed rate constants were plotted against reported σ values to define the Hammett correlation (Figure 3c).21 Generally, Hammett ρ values range from +5 to −5,22 with greater absolute values associated with greater buildup of charge at the reactive center. We anticipated that a positive charge would develop at the anomeric center in these reactions, narrowing the range of ρ values to between 0 and approximately −5.23 As expected, a linear relationship with a ρ value (slope) of −5.1 indicated a distinctly positive SN1 transition state.

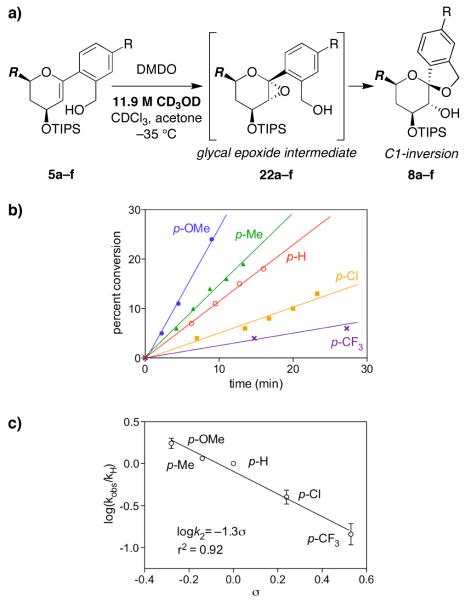

Hammett Analysis of MeOH-Catalyzed Epoxide-Opening Spirocyclization via a Proposed SN2 Mechanism.

We next used the analogous analysis to probe the transition state for the MeOH-catalyzed epoxide-opening spirocyclization with inversion of configuration (Figure 4a). If an SN2 mechanism is operative (Figure 2, pathway A), the ρ value should be closer to zero than that observed for the TsOH epimerization above. In contrast, if the epoxide-opening spirocyclization occurs via an SN1 mechanism involving a discrete oxocarbenium intermediate (Figure 2, pathway B), the ρ value should be similar to that of the TsOH epimerization.

Figure 4.

Hammett analysis of methanol-catalyzed epoxide-opening spirocyclization via a proposed SN2 mechanism. a) Methanol-catalyzed epoxide-opening spirocyclization of glycal epoxides 22a–f with inversion of configuration to afford spiroketals 8a–f. R = CH2CH2OTBDPS. b) Rates of inversion product formation with 11.9 M CD3OD (4:3:1.3 CD3OD/CDCl3/acetone) at −35 °C. The p-methoxy-substituted substrate 5a also forms the corresponding retention product 11a, but the diagnostic NMR peaks are resolved. The linear fit for the p-CF3-substituted substrate 5e is based upon a total of seven datapoints out to 52 min,25 although only the first three datapoints are shown for clarity. The p-nitro-substituted glycal epoxide intermediate 22f does not react at this temperature. Representative data from one of three replicate experiments shown. c) Hammett plot exhibits a linear correlation for the electronically varied substrates 22a–e with a shallow negative slope indicative of an SN2 transition state (ρ = −1.3).

Thus, CD3OD-catalyzed spirocyclization with inversion of configuration of the glycal epoxides 22a–f generated in situ from 5a–f (−78 °C, 10 min) was monitored in 11.9 M CD3OD at −35 °C by NMR (Figure 4b). Rate constants were again determined using the method of initial rates, and the logarithms of the observed rate constants were plotted against reported σ values (Figure 4c).21 The resulting Hammett correlation exhibited a negative slope with a ρ value of −1.3, consistent with an SN2 (or SN2-like) transition state.14f,15c,d,18,24 The slope was significantly shallower than that observed for the SN1 process above (ρ = −5.1), indicating the smaller electronic influence of the aryl substituents upon this SN2 reaction.

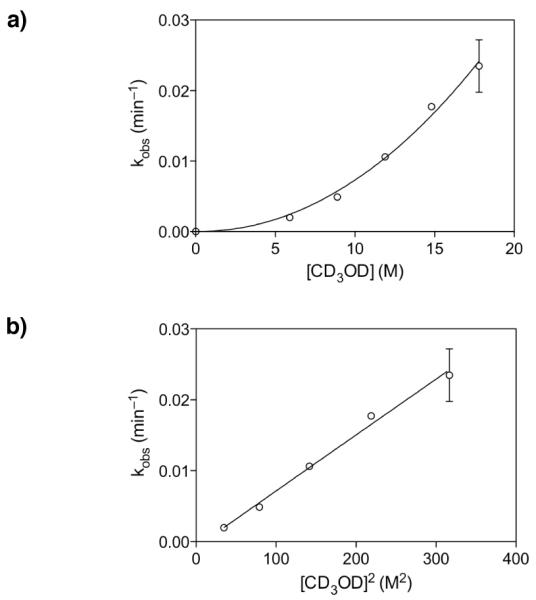

Kinetic Analysis of MeOH-Catalyzed Epoxide-Opening Spirocyclization.

To assess the role of MeOH in hydrogen-bonding catalysis of the epoxide-opening spirocyclization with inversion of configuration, we determined the kinetic order of MeOH in the transition state. Thus, the initial rates of spirocyclization of the glycal epoxide 22c (R = H) derived in situ from glycal 5c (R = H) were measured in the presence of varying CD3OD concentrations at −35 °C by NMR.25 A polynomial curve was obtained, suggesting more than one equivalent of MeOH in the transition state (Figure 5a). Non-linear least squares fit of the data to the equation f(x) = c[x]n gave values of c = 6.1×10−5 and n = 2.1, consistent with second-order catalysis by MeOH. Indeed, plotting the observed rate against [CD3OD]2 yielded a linear fit with r2 = 0.96 (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Second-order catalysis by methanol in the epoxide-opening spirocyclization of glycal epoxide 22c (R = H). a) Plot of kobs (min−1) for inversion product formation at varying [CD3OD] yields a polynomial curve. Mean values over two replicate experiments shown. b) Plot of kobs (min−1) versus [CD3OD]2 yields a linear correlation, consistent with second-order dependence on methanol. Mean values over two replicate experiments shown.

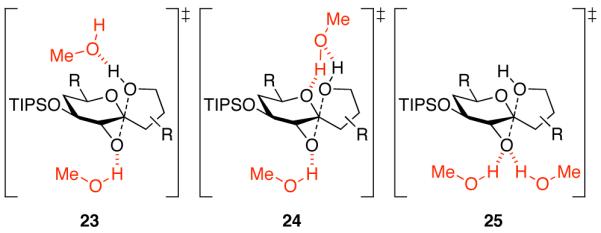

Based on these data, we envision three possible transition states (Figure 6). In transition state 23, one molecule of MeOH interacts with the epoxide oxygen and another with the attacking nucleophilic alcohol by hydrogen-bonding interactions. In transition state 24, one MeOH again interacts with the epoxide oxygen, while the second MeOH engages in two hydrogen bonds to both the alcohol nucleophile and the tetrahydropyran ring oxygen. In this model, the second MeOH may direct the nucleophile to anti-attack and also enhance reaction selectivity by disfavoring oxocarbenium formation in competing SN1 pathways. In transition state 25, both MeOH molecules participate in hydrogen-bonding activation of the epoxide leaving group. This transition state mimics the active site mechanism proposed in epoxide hydrolase enzymes.26,27

Figure 6.

Three possible SN2 transition states for MeOH-catalyzed epoxide-opening spirocyclization with inversion of configuration under MeOH hydrogen-bonding catalysis. In transition state 23, both the epoxide leaving group and alcohol nucleophile are activated with separate MeOH hydrogen bonds. Transition state 24 is similar, but the upper MeOH also engages in a second hydrogen bond to the tetrahydropyran ring oxygen that may disfavor competing SN1 mechanisms involving oxocarbenium formation. In transition state 25, the epoxide electrophile is activated by two MeOH hydrogen bonds, as seen in epoxide hydrolase enzymes.26

Strikingly, Jamison and coworkers have also reported second-order catalysis by water in their studies of regioselective epoxide-opening cascades to generate ladder polyethers, and have proposed related hydrogen-bonding interactions in their systems.9a,b

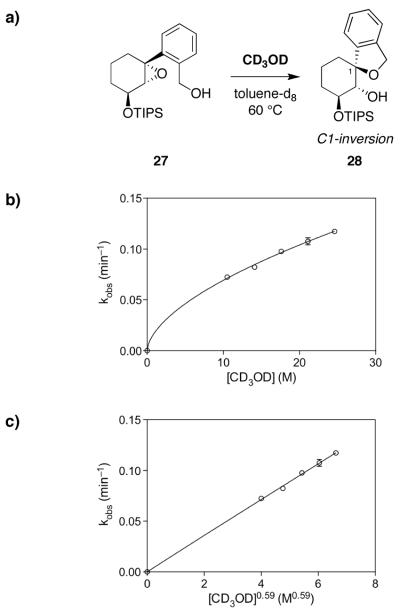

Role of the Glycal Ring Oxygen in MeOH-Catalyzed Epoxide-Opening Spirocyclization.

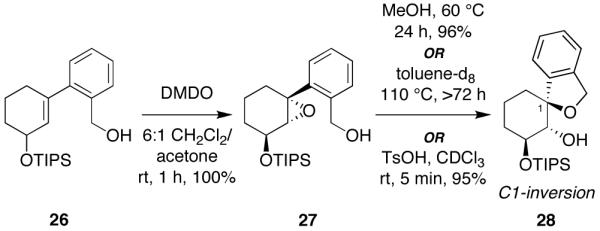

One of the proposed transition states for the MeOH-catalyzed epoxide-opening spirocyclization invokes hydrogen bonding between the glycal ring oxygen and one molecule of MeOH (24, Figure 6). This proposal is attractive in that this interaction might also disfavor competing oxocarbenium formation leading to alternative SN1 pathways. Thus, to investigate the possible role of this glycal ring oxygen, we explored an analogous carbocyclic system lacking that ring oxygen (Figure 7). As expected, the cyclohexene substrate 26 was less reactive to DMDO oxidation, requiring much higher temperature and longer reaction time than the analogous glycals. Moreover, the resulting cyclohexene oxide intermediate 27 could be isolated at rt, facilitating the introduction of other solvents prior to the subsequent spirocyclization step.

Figure 7.

Epoxide-opening spirocyclizations of a cyclohexene oxide substrate lacking the glycal ring oxygen. The thermal spirocyclization in toluene-d8 proceeds to only 85% conversion even after 72 h. Stereochemical assignments were determined by 1H-NMR and NOESY analysis of the spiroether product.

Spirocyclization of 27 in neat MeOH (24.6 M) required warming to 60 °C and 24 h reaction time, affording the spiroether 28 with inversion of configuration. Reaction in toluene-d8 required even higher temperature and longer reaction time (110 °C, 72 h, 85% conversion), establishing the catalytic activity of MeOH in this reaction. Interestingly, treatment of epoxide 27 with TsOH led to rapid conversion to spiroether 28, again with inversion of configuration, despite the presumably contrathermodynamic nature of this product (axial aryl group observed by NMR).25 That epoxide opening occurs with inversion of configuration even with TsOH further emphasizes the differences in reactivity between alkyl epoxides such as 27 and those studied previously by Jamison and coworkers,9 and the corresponding glycal epoxides that are the focus of this study (cf. Figure 3), for which stereoselectivity becomes a key consideration due to the electronic influence of the glycal ring oxygen.

We next determined the kinetic order of MeOH in the transition state of the spirocyclization of cyclohexene oxide 27 to spiroether 28 (Figure 8a), for comparison to our results with the analogous glycal epoxide 22c. Initial rates of spirocyclization were measured in the presence of varying CD3OD concentrations at 60 °C by NMR (Figure 8b). There was no reaction in neat toluene ([CD3OD] = 0) at 60 °C over the timescale of these experiments. Intriguingly, fitting the data to f(x) = c[x]n gave values of c = 1.8×10−2 and n = 0.59, indicative of fractional-order kinetics. Indeed, plotting the observed rate against [CD3OD]0.59 yielded a linear fit with r2 = 0.99 (Figure 8c). Fractional orders often suggest a complex kinetic scenario.28

Figure 8.

Fractional-order catalysis by methanol in the epoxide-opening spirocyclization a substrate lacking the glycal ring oxygen. a) Methanol-catalyzed epoxide-opening spirocyclization of cyclohexene oxide 27 with inversion of configuration to afford spiroether 28. b) Plot of kobs (min−1) for spiroether formation at varying [CD3OD] yields a fractional-order curve. Mean values over two replicate experiments shown. c) Plot of kobs (min−1) versus [CD3OD]0.59 yields a linear correlation, consistent with the fractional-order dependence on methanol. Mean values over two replicate experiments shown.

Importantly, this result clearly demonstrates that the glycal ring oxygen, while not required for MeOH catalysis in general, is required for second-order catalysis of the epoxide-opening spirocyclization reaction. This may also be considered additional circumstantial support for proposed transition state 24 (Figure 6), which is the only one of the three structures that invokes a specific interaction with the ring oxygen, although removal of the ring oxygen also clearly results in a drastic decrease in the inherent reactivity of the epoxide electrophile, which could certainly cause the change in mechanism. In addition, it remains a formal possibility that subtle steric or conformational changes resulting from replacement of the ring oxygen with a methylene group could also disable either of the other proposed transition states 23 or 25.

Inhibition of MeOH-Catalyzed Epoxide-Opening Spirocyclization by Acetone.

The in situ DMDO epoxidations of the glycal substrates are carried out at −78 °C, a temperature at which spirocyclization does not occur (Table 3), making this step insignificant in our kinetic analyses. However, this step necessarily introduces acetone into the reaction milieu, which remains present during the epoxide-opening spirocyclization reaction.29 Under our typical reaction conditions, acetone is maximally one-seventh of the total reaction volume (1.9 M), a relatively minor component. Nonetheless, since acetone is both a hydrogen-bond acceptor and an electrophile that may react with MeOH, it is possible that this cosolvent could affect the spirocyclization reaction. Indeed, initial studies indicated that increased relative acetone concentrations led to increased methyl glycoside formation and decreased stereoselectivity.5,30

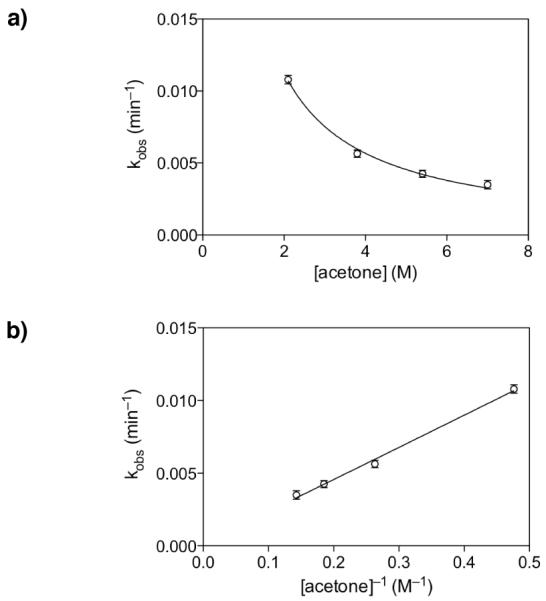

Thus, to determine the potential role of acetone in the spirocyclization reaction, initial rates of spirocyclization of the glycal epoxide 22c (R = H) derived in situ from glycal 5c (R = H) were measured in the presence of varying acetone concentrations and constant CD3OD concentration (11.9 M) at −35 °C by NMR.31 An inhibitory curve was obtained when the rate of spirocyclization was plotted as a function of acetone concentration (Figure 9a). Fitting the data to f(x) = c[x]n gave values of c = 2.2×10−2 and n = −1.0, indicative of first-order inhibition. Indeed, plotting the observed rate against [acetone]−1 yielded a linear fit with r2 = 0.99 (Figure 9b).

Figure 9.

First-order inhibition by acetone in the epoxide-opening spirocyclization of glycal epoxide 22c (R = H). a) Plot of kobs (min−1) for inversion product formation at varying [acetone] yields an inhibitory curve. Mean values over two replicate experiments shown. b) Plot of kobs (min−1) versus [acetone]−1 yields a linear correlation, consistent with negative first-order dependence on acetone. Mean values over two replicate experiments shown.

The inhibitory activity of acetone suggests that it may sequester MeOH catalyst molecules, lowering the effective concentration of MeOH, leading to a lower rate of spirocyclization and decreased stereoselectivity for inversion of configuration. However, simple subtraction of [acetone] from [MeOH] is insufficient to explain the rate decreases observed in Figure 9. This suggests that complex solvent interactions are involved, in which acetone alters the catalytic activity of MeOH in a non-linear fashion. Indeed, previous experimental and computational studies have shown that the hydrogen-bonded network of MeOH species in neat MeOH is both complex and significantly reorganized by the addition of a hydrogen-bond acceptor such as acetone.32 Within the range of acetone concentrations examined herein, reorganizations have been described that decrease higher-order MeOH branching off of hydrogen-bonded MeOH chains. Thus, higher concentrations of acetone may disfavor related higher-order MeOH hydrogen-bonding interactions required in the transition state necessary for selective epoxide opening (cf. 24, 25, Figure 6).

Additionally, the previously observed increase in competing methyl glycoside formation5,30 in the presence of increased acetone concentrations suggests that this side reaction becomes more competitive at lower effective concentrations of MeOH (vide infra).

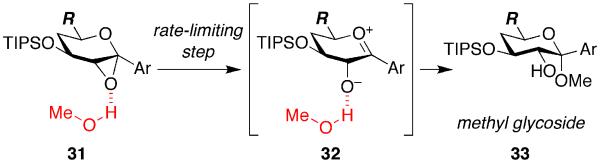

Competing Intermolecular Methyl Glycoside Formation.

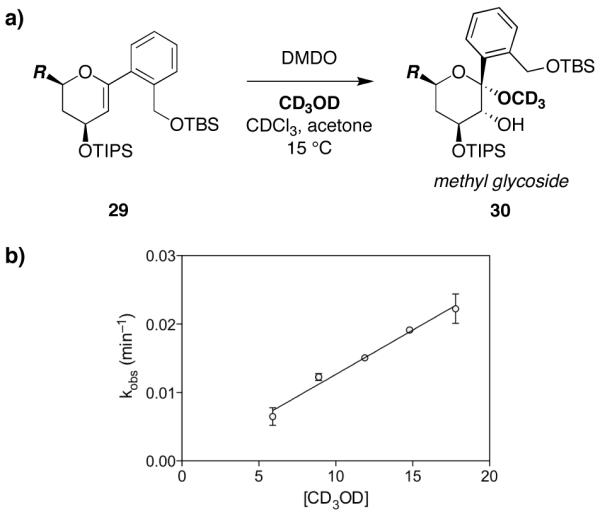

Intermolecular addition of MeOH is a side reaction that can be competitive with the desired epoxide-opening spirocyclization. In our initial studies, we found that, paradoxically, decreased MeOH concentration led to a profound increase in this competing side reaction.5 As noted above, increased acetone concentrations also lead to increased methyl glycoside formation.5,30 To understand these effects, we carried out kinetic analysis of the methyl glycoside formation reaction using a substrate that cannot undergo spirocyclization.

Thus, the primary alcohol functionality of glycal 5c (R = H) was protected as a TBS ether in 29 (Figure 10a). This glycal was then epoxidized with DMDO (−78 °C, 10 min) and initial rates of methyl glycoside formation were measured in the presence of varying CD3OD concentrations at 15 °C by NMR. Notably, this intermolecular reaction requires a much higher temperature than the corresponding intramolecular spirocyclization, which occurs at −35 °C (cf. Table 3). Fitting the data to f(x) = c[x]n gave values of c = 1.3×10−3 and n = 1.0, indicative of first-order dependence of the methyl glycoside formation reaction upon methanol, and plotting the observed rate against [CD3OD] yielded a linear fit with r2 = 0.94.

Figure 10.

First-order dependence on methanol in the intermolecular methyl glycoside formation side reaction. a) Methanolysis of the glycal epoxide generated in situ from protected glycal 29 to afford methyl glycoside 30. b) Plot of kobs (min−1) versus [CD3OD] yields a linear correlation, consistent with first-order dependence on methanol. Mean values over two replicate experiments shown.

We also observed that the methyl glycoside 30 is formed with retention of configuration at the anomeric carbon.33 At this elevated temperature of 15 °C, we posit that the reaction occurs via an SN1 mechanism, involving initial methanol-catalyzed epoxide opening to an oxocarbenium intermediate 32 in the rate-limiting step,34 followed by stereoelectronically favored axial attack of methanol (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Proposed SN1 mechanism for competing intermolecular methyl glycoside-forming side reaction.

Based on these results, it is evident that decreased MeOH concentrations lead to increased methyl glycoside formation by decreasing the relative rate of the desired spirocyclization, as the intermolecular reaction is first-order dependent upon MeOH while the intramolecular reaction is second-order dependent upon MeOH. This is, perhaps, not surprising, as an intermolecular reaction via any of the proposed SN2 transition states (Figure 6) would require three molecules of methanol, with third-order dependence likely rendering that reaction manifold kinetically inaccessible. These results are also consistent with the increased methyl glycoside formation observed in the presence of increased acetone concentrations above, whereby acetone lowers the effective concentration of MeOH, increasing the relative rate of the intermolecular reaction compared to the intramolecular reaction.

Interestingly, in their studies of regioselective epoxide-opening cascades, Jamison and coworkers have reported that differential kinetic orders of dependence upon water similarly influence the relative rates of competing endo and exo reaction manifolds, playing a critical role in the regioselectivity of those reactions.9b

Finally, the fact that a single equivalent of MeOH is sufficient to catalyze epoxide opening in the intermolecular SN1 manifold suggests that only one such hydrogen-bonding interaction is likewise required in the SN2 epoxide-opening spirocyclization reaction, in contrast to alternative bidentate activation mechanisms precedented in epoxide hydrolase enzymes (23,24 vs. 25, Figure 6).

CONCLUSION

We have obtained intriguing mechanistic details about the stereoselective MeOH-catalyzed epoxide-opening spirocyclization of glycal epoxides through low-temperature NMR studies of substituted C1-aryl substrates. Hammett analyses of reaction kinetics are consistent with spirocyclization via an SN2 or SN2-like mechanism (ρ = −1.3 vs. ρ = −5.1 for SN1 reactions of these substrates), leading to inversion of configuration at the anomeric carbon. Additional support for an SN2 mechanism is provided by the trend toward enhanced stereoselectivity for inversion of configuration observed with electron-deficient substrates that disfavor oxocarbenium formation in competing SN1 mechanisms. The reaction exhibits second-order dependence on MeOH, with hydrogen-bonding interactions between the substrate and two molecules of MeOH proposed in the spirocyclization transition state (Figure 6). Notably, the glycal ring oxygen is required for second-order MeOH catalysis. Conversely, acetone cosolvent acts as a first-order inhibitor of the reaction, presumably reducing the effective concentration of MeOH by altering its hydrogen-bonding activity. The previous paradoxical finding that decreased MeOH concentrations lead to increased competing intermolecular methyl glycoside formation is resolved by the determination that this side reaction is only first-order dependent on MeOH, proceeding via a presumed SN1 mechanism. Taken together, the results support a proposed transition state 24, in which one molecule of MeOH activates the epoxide oxygen while the second chelates both the incoming nucleophile and the glycal ring oxygen to disfavor oxocarbenium formation and possibly to direct anti attack.

In our initial report, we noted that other alcohols (EtOH, i-PrOH, CF3CH2OH, [CF3]2CHOH) proved to be inferior catalysts in this epoxide-opening spirocyclization reaction with respect to stereo- and/or chemoselectivity.5 It is apparent that numerous features make MeOH an optimal catalyst for this reaction, including appropriate hydrogen-bonding strength, low acidity, low freezing point, small steric size, low cost, and volatility to facilitate product recovery. While water could theoretically also be an effective catalyst,9 its use in this reaction is precluded by its higher freezing point, as the glycal epoxides undergo spontaneous thermal spirocyclization even at temperatures below 0 °C (Table 3).

Overall, these studies provide fundamental new insights into the dramatic, specific roles that simple solvents such as MeOH and acetone can play in hydrogen-bonding catalysis and inhibition of stereoselective epoxide-opening reactions of complex molecules. In these systems, MeOH plays a critical role both in providing stereoselectivity (SN2 vs. SN1) and in discriminating between competing reaction manifolds (intra- vs. intermolecular). The resulting spiroketal products represent key structural motifs in a wide range of natural products, and MeOH catalysis provides stereocontrolled access to contrathermodynamic spiroketals that are not readily accessible using other synthetic methods. Further, these findings raise the possibility that specific solvent catalysis may be an underappreciated factor in other reactions as well.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Dedicated to the memory of our colleague and mentor, Prof. David Y. Gin (1967–2011), with our gratitude for his thoughtful guidance, steadfast support, and invaluable insights into this project. We thank Prof. Dale Drueckhammer (Stony Brook) and Prof. Minkui Luo (MSKCC) for helpful discussions and Dr. George Sukenick, Dr. Hui Liu, Hui Fang, and Dr. Sylvi Rusli for expert NMR and mass spectral support. D.S.T. is an Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellow. Financial support from the NIH (P41 GM076267), Tri-Institutional Stem Cell Initiative, and Starr Cancer Consortium is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. Complete experimental procedures, characterization data for all new compounds, and kinetic data in tabular format. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Schreiner PR. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2003;32:289–296. doi: 10.1039/b107298f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Taylor MS, Jacobsen EN. Angew. Chem. Intl. Ed. 2006;45:1520–1543. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Wassermann A. J. Chem. Soc. 1942:618–621. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yates P, Eaton P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960;82:4436–4437. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Hine J, Linden S-M, Kanagasabapathy VM. J. Org. Chem. 1985;50:5096–5099. [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Rink R, Kingma J, Spelberg JHL, Janssen DB. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5600–5613. doi: 10.1021/bi9922392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yamada T, Morisseau C, Maxwell JE, Argiriadi MA, Christianson DW, Hammock BD. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:23082–23088. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001464200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Potuzak JS, Moilanen SB, Tan DS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13796–13797. doi: 10.1021/ja055033z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Liu G, Wurst JM, Tan DS. Org. Lett. 2009;11:3670–3673. doi: 10.1021/ol901437f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Moilanen SB, Potuzak JS, Tan DS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:1792–1793. doi: 10.1021/ja057908f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).(a) Aho JE, Pihko PM, Rissa TK. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:4406–4440. doi: 10.1021/cr050559n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Perron F, Albizati KF. Chem. Rev. 1989;89:1617–1661. [Google Scholar]

- (9).(a) Vilotijevic I, Jamison TF. Science. 2007;317:1189–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.1146421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Byers JA, Jamison TF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:6383–6385. doi: 10.1021/ja9004909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Morten CJ, Jamison TF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:6678–6679. doi: 10.1021/ja9025243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Morten CJ, Byers JA, Jamison TF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:1902–1908. doi: 10.1021/ja1088748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Lotesta S, Kiren S, Sauers R, Williams L. Angew. Chem. Intl. Ed. 2007;46:7108–7111. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).(a) Lemieux RU, Hendriks KB, Stick RV, James K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975;97:4056–4062. [Google Scholar]; (b) Banait NS, Jencks WP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:7951–7958. [Google Scholar]; (c) Nukada T, Berces A, Zgierski MZ, Whitfield DM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:13291–13295. [Google Scholar]; (d) Jung K–H, Müller M, Schmidt RR. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:4423–4442. doi: 10.1021/cr990307k. 4442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Garcia BA, Gin DY. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:4269–4279. [Google Scholar]; (f) Bérces A, Enright G, Nukada T, Whitfield DM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:5460–5464. doi: 10.1021/ja001194l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Jensen KJ. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 2002:2219–2233. [Google Scholar]; (h) Crich D, Chandrasekera NS. Angew. Chem. Intl. Ed. 2004;43:5386–5389. doi: 10.1002/anie.200453688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Kim J-H, Yang H, Park J, Boons G-J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:12090–12097. doi: 10.1021/ja052548h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) El-Badri MH, Willenbring D, Tantillo DJ, Gervay-Hague J. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:4663–4672. doi: 10.1021/jo070229y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Zhu X, Schmidt R. Angew. Chem. Intl. Ed. 2009;48:1900–1934. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Mydock LK, Demchenko AV. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010;8:497–510. doi: 10.1039/b916088d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).(a) Piszkiewicz D, Bruice TC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967;89:6237–6243. [Google Scholar]; (b) Piszkiewicz D, Bruice TC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968;90:2156–2163. doi: 10.1021/ja01010a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sinnott ML, Jencks WP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:2026–2032. [Google Scholar]; (d) Namchuk MN, McCarter JD, Becalski A, Andrews T, Withers SG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:1270–1277. [Google Scholar]; (e) Stubbs JM, Marx D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:10960–10962. doi: 10.1021/ja035600n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Beaver MG, Woerpel KA. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:1107–1118. doi: 10.1021/jo902222a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).(a) Winstein S, Grunwald E, Jones HW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1950;73:2700–2707. [Google Scholar]; (b) Frisone GJ, Thornton ER. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968;90:1211–1215. [Google Scholar]; (c) Bentley TW, Schleyer P. v. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976;98:7658–7666. [Google Scholar]; (d) Arnett EM, Petro C, Schleyer P. v. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;101:522–526. [Google Scholar]; (e) Koo IS, An SK, Yang K, Lee I, Bentley TW. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2002;15:758–764. [Google Scholar]

- (14).(a) Baker JW. J. Chem. Soc. 1933:1128–1133. [Google Scholar]; (b) Baker JW, Nathan WS. J. Chem. Soc. 1935:519–527. [Google Scholar]; (c) Baker JW, Nathan WS. J. Chem. Soc. 1935:1840–1844. [Google Scholar]; (d) Sugden W, Willis JB. J. Chem. Soc. 1951:1360–1363. [Google Scholar]; (e) Amyes TL, Richard JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:9507–9512. doi: 10.1021/ja00182a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Buckley N, Oppenheimer NJ. J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:7360–7372. doi: 10.1021/jo960729j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Toteva MM, Richard JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:9798–9805. doi: 10.1021/ja026849s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).(a) Richard JP, Jencks WP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:4689–4691. [Google Scholar]; (b) Richard JP, Jencks WP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:4691–4692. [Google Scholar]; (c) Lim C, Kim S–H, Yoh S–D, Fujio M, Tsuno Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:3243–3246. [Google Scholar]; (d) Yoh SD, Cheong DY, Lee CH, Kim SH, Park JH, Fujio M, Tsuno Y. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2001;14:123–130. [Google Scholar]

- (16).(a) Young PR, Jencks WP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977;99:8238–8248. [Google Scholar]; (b) Amyes TL, Jencks WP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:7900–7909. [Google Scholar]; (c) Buckley N, Oppenheimer NJ. J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:8048–8062. doi: 10.1021/jo960748t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Liras JL, Lynch VM, Anslyn EV. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:8191–8200. [Google Scholar]; (e) Shenoy SR, Woerpel KA. Org. Lett. 2005;7:1157–1160. doi: 10.1021/ol0500620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Krumper JR, Salamant WA, Woerpel KA. Org. Lett. 2008;10:4907–4910. doi: 10.1021/ol8019956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Krumper JR, Salamant WA, Woerpel KA. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:8039–8050. doi: 10.1021/jo901639b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).(a) Gold V. J. Chem. Soc. 1956:4633–4637. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ingold CK. Structure and Mechanism in Organic Chemistry. 2nd ed. Cornell University Press; Ithaca, NY: 1969. [Google Scholar]; (c) Bartlett PD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94:2161–2170. [Google Scholar]; (d) Sneen RA. Acc. Chem. Res. 1973;6:46–53. [Google Scholar]; (e) Jencks WP. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1981;10:345–375. [Google Scholar]; (f) Katritzky AR, Brycki BE. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1990;19:83–105. [Google Scholar]; (g) Buckley N, Oppenheimer NJ. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:540–551. doi: 10.1021/jo9620977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Smith MB, March J. March’s Advanced Organic Chemistry. 6th ed. Wiley; New York: 2007. Chapter 10. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Phan TB, Nolte C, Kobayashi S, Ofial AR, Mayr H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:11392–11401. doi: 10.1021/ja903207b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).(a) Jorge JAL, Kiyan NZ, Miyata Y, Miller J. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2. 1981:100–103. [Google Scholar]; (b) Vitullo VP, Grabowski J, Sridharan S. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1981:737–738. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Our original experimental protocol (ref. 5; 92:0:8 ratio of 18:19:20) called for rapid addition of MeOH to the −63 °C CH2Cl2/acetone solution of the glycal epoxide, which likely resulted in transient warming of the reaction mixture to a temperature at which the spirocyclization occurred. The reaction may also have proceeded during warming from −63 °C to rt prior to workup. Along these lines, low-temperature NMR analysis of the reaction during that warming process (−63 °C → rt over 15 min) herein indicated formation of a 80:0:20 ratio of 18:19:20.

- (21).Hansch C, Leo A, Taft RW. Chem. Rev. 1991;91:165–195. [Google Scholar]

- (22).(a) Hammett LP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1937;59:96–103. [Google Scholar]; (b) Carpenter BK. Determination of Organic Reaction Mechanisms. Wiley; United States: 1984. Chapter 7. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Absolute ρ values between 0 and 1 are usually seen as radical reactions, further narrowing our range of expected Hammett correlation values. (e.g., Pryor WA, Lin TH, Stanley JP, Henderson RW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:6993–6998.

- (24).Interestingly, while there are many precedents for U- or V-shaped curves in Hammett correlations for SN2 reactions at benzylic centers, the plot had fairly good linearity in this case (r2 = 0.92). Hammett plot curvatures across different substituents have been attributed to changing mechanism from SN1 to SN2, changing polarity of the transition state (degree of bond formation vs. cleavage), changing ability to stabilize the transition state based on different inductive and resonance capacities, or changing electrostatic interactions between reaction partners. In this case, the negative ρ value is indicative of positive charge buildup at the reactive center. If the C1-aryl ring is in full conjugation with the reactive center in the transition state, a positive deviation in the left portion of the plot would be expected, indicating enhanced rate acceleration due to resonance effects for the p-OMe and p-Me substituents. Alternatively, if the C1-aryl ring is fully out of conjugation from the reactive center, as is the case in the spiroketal product, a negative deviation in the left portion of the plot would be expected, due to inductive electron-withdrawing effect of the p-OMe substituent. Accordingly, the linear plot observed is suggestive of a transition state in which the aromatic ring is partially conjugated to the reactive center. For lead references on the analysis of SN2 reactions of benzylic systems, see: Young PR, Jencks WP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;101:3288–3294. Galabov B, Nikolova V, Wilke JJ, Schaefer HF, Allen WD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9887–9896. doi: 10.1021/ja802246y.

- (25).See Supporting Information for full details.

- (26).Lau EY, Newby ZE, Bruice TC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:3350–3357. doi: 10.1021/ja0037724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Attempts to distinguish between these possible transition states using computational methods have been unsuccessful thus far.

- (28).Smith MB, March J. March’s Advanced Organic Chemistry. 6th ed. Wiley; New York: 2007. Chapter 6. [Google Scholar]

- (29).(a) DMDO is prepared from acetone and was delivered herein as an 0.073 M solution in acetone: Murray RW, Jeyaraman R. J. Org. Chem. 1985;50:2847–2853. (b) Previous efforts in our laboratory to generate acetone-free DMDO using a published protocol have been unsuccessful: Gilbert M, Ferrer M, Sanchez-Baeza F, Messeguer A. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:8643–8650. (c) In addition, the epoxidation reaction itself produces one equivalent of acetone as a byproduct.

- (30).Potuzak JS. PhD. Dissertation. Cornell University; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Acetone-d6 was added prior to treatment with DMDO in acetone-h6 to achieve higher acetone concentrations in these experiments.

- (32).For lead references on MeOH–acetone liquid mixtures, see: Venables DS, Schmuttenmaer CA. J. Chem. Phys. 2000;113:3249–3260. Max J-J, Chapados C. J. Chem. Phys. 2005;122:014504/1–18. doi: 10.1063/1.1790431.

- (33).Methyl glycosides 16a–e (cf. Table 2) were similarly observed exclusively with retention of configuration at the anomeric carbon. Interestingly, this stereoselectivity in the aryl substrate series is not seen in the aliphatic substrate series, where both glycoside anomers are observed (ref. 5). This may result from the increased steric bulk of the C1-aryl substituent in 30, further disfavoring an axial orientation.

- (34).For a lead reference on glycoside hydrolysis via SN1 mechanisms, see: Ahmad IA, Birkby SL, Bullen CA, Groves PD, Lankau T, Lee WH, Maskill H, Miatt PC, Meneer ID, Shaw K. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2004;17:560–566.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.