Intussusception is defined as the invagination of a portion of bowel into the lumen of the adjacent segment of bowel [15]. Intussusception, one of the causes of intestinal obstruction, is not a common gastrointestinal condition in cattle [12,15,16] and is usually seen in calves less than two months old [5]. The cause of an intussusception is often unknown but any condition that alters intestinal motility has been implicated [1,5]. It is suggested that intussusception can represent a diagnostic challenge in cattle medicine. History, clinical and clinicopathologic examinations are important in the diagnosis of intussusception [5,14]. Although ultrasonography has been commonly used as a diagnostic tool to detect internal diseases of large animals, there is limited ultrasonographic data demonstrating intussusceptions in cattle [4,7,3]. This case report describes a small intestinal intussusception in a cow and the transrectal ultrasonographic view of the lesion.

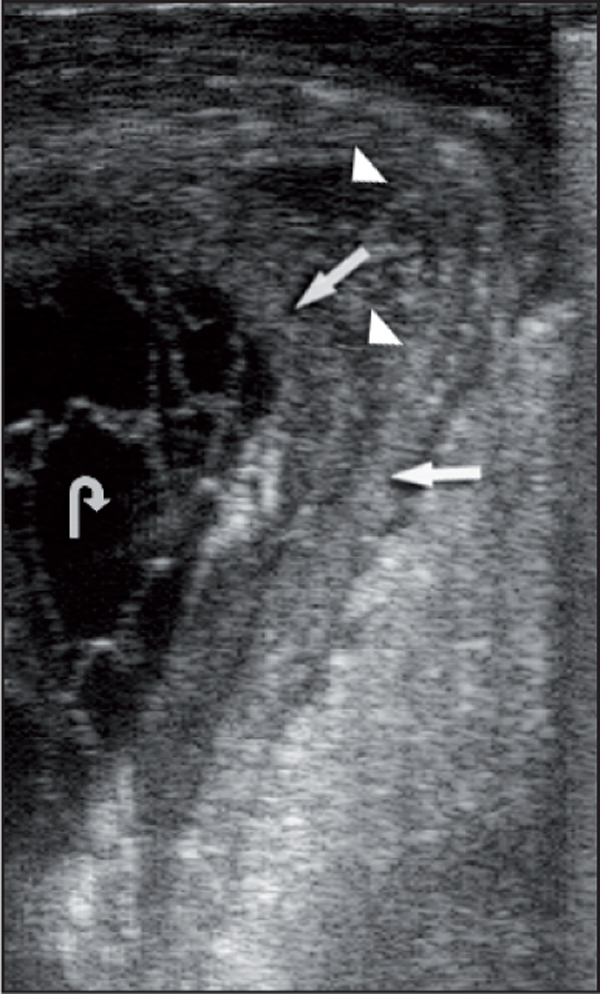

In November 2005, a four-year-old, non-pregnant Simmental cow, with a history of anorexia, colic and a lack of defaecation was submitted to the clinic after two days without treatment. Values for rectal temperature, pulse and respiratory rate were 38.2°C, 100 beats/minute and 20 breaths/minute, respectively. Ruminal contractions were markedly reduced (two contractions every five minutes). The cow showed mild abdominal pain. Auscultation with percussion over the right flank was negative and abdominal distention was not evident. Rectal examination revealed the presence of a firm mass on the left of the median line and cranial to the pelvis. There was no faecal material in rectum. No distended loops of small intestine were palpable on rectal examination. The firm mass was examined using an 8-MHz rectal transducer (100 Falco, Pie Medical). The transducer was placed in a rectal palpation sleeve containing transducer coupling gel and inserted per rectum. The longitudinal ultrasound view of the firm mass revealed several echogenic parallel densities with a hypoechogenic central core representing the intestinal lumen of the intussusception (Figure 1). Ultrasonographic examination of the right flank failed to reveal dilated loops of small intestine.

Figure 1.

The ultrasonographic appearance of the intussusception. This sonogram was obtained transrectally with an 8-MHz rectal transducer. Mildly echogenic densities represent bowel walls (arrows). Hypoechogenic areas among the echogenic linear densities probably represent oedema (arrowheads). The hypoechogenic central core indicates the intestinal lumen of the intussusception (curved arrow).

The cow was slightly dehydrated. Haematocrit value, total serum protein and fibrinogen concentrations were 36% (reference range 24-46%), 7 g/dl (reference range 6.7-7.5 g/dl), and 600 mg/dl (reference range 100-600 mg/dl), respectively. Clinical pathology revealed that there was a mild hyperglycemia (5.1645 mmol/L; reference range 2.4975-4.1625 mmol/L), hypocalcaemia (1.675 mmol/L; reference range 2.425-3.1 mmol/L) and a slight hypochloraemia (93 mmol/L; reference range 97-111 mmol/L). Serum urea, creatinine, potassium and sodium concentrations were all within the normal range.

Based on the history and the results of physical, ultrasonographic and biochemical examination, a tentative diagnosis of intussusception was made and the cow was submitted for surgery. Surgery was performed by a right flank laparotomy with the cow in a standing position, under local infiltration analgesia using 2% lidocaine hydrochloride (Vilcain; Vilsan, Ankara, Turkey). The intussusception was found. However, it could not be reduced by manual traction. An end-to-end anastomosis was performed following the jejunoileal resection. Postoperative therapy included 0.9% sodium chloride (10 L iv, daily) (Eczacibasi-Baxter, Istanbul, Turkey) for two days and penicillin (Strepto-Veticilline; Eczacibasi-Baxter, Istanbul, Turkey) for five days. The cow became appetent one day post surgery and made steady improvement over the following ten days. The resected bowel segment (Figure 2) was placed in formalin for subsequent histopathological examination. Histopathological examination confirmed that the intussusceptum was distal jejunum and that the intussucipiens was ileum.

Figure 2.

The view of the resected bowel segment.

Different types of intussusception have been recognised in cattle such as enteric, ileoileal, ileocecocolic, cecocolic and colocolic. Among these types, the enteric type of intussusception which occurs with invagination of one segment of the small intestine into another (usually distal jejunum or the ileum), is the most common form in cattle [17,5]. Enteric intussusception was diagnosed in this case. Although the majority of intussusceptions are idiopathic, intussusception may result from enteritis, intestinal parasitism, abrupt dietary changes, drug-induced changes in intestinal motility, mural or luminal intestinal lesions and foreign bodies [8,17,18,11,10,5]. The prevalence of enteric intussusception in cattle has been attributed to the length and mobility of the jejunal mesenteric attachments, especially the distal third [15]. Based on history, clinical examination findings on laparotomy and pathological findings, the cause of intussusception couldn't be determined in this case.

Classic signs of intussusception are, initially, either chronic low grade pain or acute signs of abdominal pain, followed by progressive inappetence, abdominal distention, a reduction in faecal volume and lethargy [13]. The cow showed slight signs of colic, anorexia, lack of defaecation and lethargy but no abdominal distention. In the diagnosis of small intestinal obstruction, rectal palpation is considered valuable. Although intussusception is palpable in only a minority of affected adult cattle (23%), distended loops of small intestine are palpable per rectum in 50% of cases with intussusception [5]. In this case, while the intussusception was diagnosed on the rectal examination, neither rectal palpation nor ultrasonographic examination of the right flank revealed distended loops of small intestine.

The transabdominal ultrasonographic pattern of an intussusception in cross-section has been described as 'bowel within bowel', a 'bull's eye' lesion, 'target pattern' or as a multiple layered, 'onion ring-type' mass with varying echogenities [2,3]. In longitudinal section, the typical lumen-within-a-lumen can be clearly identified and has been described as a 'sandwich' configuration [3]. Abdominal ultrasonography was attempted using a 3.5 MHz curved array with a maximal penetration depth of 17 cm, but the lesion could not be imaged probably because of the depth of the lesion.

Transrectal ultrasonography has also been employed to diagnose intussusceptions in equine medicine. The transrectal ultrasonographic pattern associated with the intussusception varies in respect to transducer placement. It has been suggested that while the target-like configuration is obtained on a transverse section of intussusception, longitudinal ultrasound views of the intussusception reveals several echogenic parallel densities and a hypoechogenic core [7]. In the present case, there were several echogenic parallel densities with a hypoechogenic central core representing the intestinal lumen of the intussusception. Moreover, hypoechogenic densities were evident in parallel with hyperechogenic areas. The transrectal ultasonographic findings of the case are similar to those described by Edens et al. [7]. The hyperechogenic densities indicate the bowel walls. Hypoechogenic parallel linear densities interspersed among hyperechogenic areas probably correspond to oedema. Lack of faecal output, signs of abdominal pain, the palpation of a firm mass on rectal examination and especially the transrectal ultrasonographic pattern of the lesion led to the suspect diagnosis of intussusception requiring immediate exploratory laparotomy. Small intestinal intussusceptions are surgically repaired by means of resection and end-to-end anastomosis in both cattle and horses [2,5,6,9], because end-to-end anastomosis causes less chance of stricture formation and leakage [5]. This technique was preferred in this cow and no complications were observed. In conclusion, transrectal ultrasonography can be a valuable diagnostic tool in cattle that have a palpable mass on rectal examination.

Acknowledgements

We express our deep appreciation to Associate Professor Murat Dabak and Professor M. Resat Ozercan.

References

- Aytug CN. Sigir Hastaliklari. Istanbul: Tumvet; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard WV, Reef VB, ReimeR JM, Humber KA, Orsini JA. Ultrasonographic diagnosis of small-intestinal intussusception in three foals. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1989;194:395–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun U. Ultrasonography in gastrointestinal disease in cattle. The Veterinary Journal. 2003;166:112–124. doi: 10.1016/S1090-0233(02)00301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun U, Pusterla N, Wild K. Ultrasonographic findings in 11 cows with a hepatic abscess. Veterinary Record. 1995;137:284–290. doi: 10.1136/vr.137.12.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constable PD, StJean G, Hull BL, Rings DM, Morin DE, Nelson DR. Intussusception in cattle: 336 cases (1964-1993) Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1997;210:531–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabak M, Unsaldi E, Gul Y. Diagnosis and treatment of intussusception in a cow. Turkish Journal of Veterinary Animal Science. 2001;25:387–389. [Google Scholar]

- Edens LM, White NA, Dabareiner RM, Sullins KE. Transrectal ultrasonographic diagnosis of an ileocaecal intussusception in a horse. Equine Veterinary Journal. 1996;28:81–83. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1996.tb01594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ein SH, Stephens CA. Intussusception: 354 cases in 10 years. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 1971;6:16–27. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(71)90663-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine-Rodgerson G, Rodgerson DH. Diagnosis of small intestinal intussuception by transabdominal ultrasonography in 2 adult horses. Canadian Veterinary Journal. 2001;42:378–380. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford TS, Freeman DE, Ross MW, Richardson DW, Martin BB, Madison JB. Ileocecal intussusception in horses: 26 cases (1981-1988) Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1990;196:121–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DD, Ellison GW. Intussusceptions in dogs ang cats. Compendium on Continuing Education for the Practicing Veterinarian. 1987;9:523–533. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson H, Pinsent HJ. Intestinal obstruction in cattle. Veterinary Record. 1977;101:162–166. doi: 10.1136/vr.101.9.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DF. Intussusception in adult cattle. Compendium on Continuing Education for the Practicing Veterinarian - Large Animal Supplements. 1980;11:S49–S53. [Google Scholar]

- Smith DF. Bovine intestinal surgery: Part 3. Modern Veterinary Practice. 1984;65:909–912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DF. Bovine intestinal surgery: Part 5. Modern Veterinary Practice. 1985;66:405–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DF. Surgery of the bovine small intestine. Veterinary Clinics of North America Food Animal Practice. 1990;6:449–60. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0720(15)30869-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson H. Intussusception in cattle. Veterinary Record. 1971;89:426–437. doi: 10.1136/vr.89.16.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson JT. Differential diagnosis and surgical management of intestinal obstruction in cattle. Veterinary Clinics of North America Large Animal Practice. 1979;1:377–394. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9846(17)30190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]