Abstract

The equine industries in Ireland are vibrant and growing. They are broadly classified into two sectors: Thoroughbred racing, and sports and leisure. This paper describes these sectors in terms of governance, education and training in equine welfare, and available data concerning horse numbers, identification, traceability and disposal. Animal welfare, and specifically equine welfare, has received increasing attention internationally. There is general acceptance of concepts such as animal needs and persons' responsibilities toward animals in their care, as expressed in the 'Five Freedoms'. As yet, little has been published on standards of equine welfare pertaining to Ireland, or on measures to address welfare issues here. This paper highlights the central role of horse identification and legal registration of ownership to safeguard the health and welfare of horses.

Keywords: equine, horse, identification, industry, Ireland, welfare

The equine industries in Ireland have been vibrant and growing. Total Thoroughbred (TB) horse sales at public auction in Ireland grew in value by 31.5% in one year alone from €145,626 in 2005 to €191,463 in 2006. The numbers of TB foals registered and horses returned in training has grown by 17.5% (from 10,214 to 12,004) and 22% (from 9,080 to 11,109), respectively, over the five years to 2006 [25]. In contrast, in 2007 as compared to 2006, although there has been a further 9.7% increase in the numbers of horses returned in training (from 11,109 to 12,188), there has been a 7% decrease (from a record €189.4 million in 2006) in the value of bloodstock sales at public auction [26]. This latter figure is sensitive indicator of current confidence in the market for young horses, and thus future trends for older animals. There are an estimated 27.5 sports/leisure horses per thousand people (the most horse-dense population in Europe), highlighting the importance of equestrianism in Ireland [23].

The role of animal welfare within the equine industries has gained increasing prominence internationally. Animal use is generally accepted by society, provided that the benefits associated with this use do not outweigh harm to the animals. When we use animals, we take on a moral obligation towards those animals [7,52]. This duty of care is informed by legislative provisions, codes of practice and guidelines aimed at safeguarding the health and welfare of animals. The aim of this paper is to describe the organisation of the equine industries in Ireland and examine how these structures relate to equine welfare concerns.

Overview of the current equine industry structures

There are two broad sectors within the Irish equine industry. The majority of TB horses in Ireland are bred for racing - non-TB horses cannot be so used - and a discrete structure can be identified for the TB racing sector. Sports horses are defined as those of all breeds and types used for recreational and competitive purposes other than racing [22]. The discussion here specifically focuses on the two sectors of racing and sports/leisure.

Overall horse numbers

The racing sector

Thoroughbred horses born in either the Republic of Ireland (ROI) or Northern Ireland (NI) are generally registered, with the suffix 'Ire', in the General Stud Book for Britain and Ireland, maintained by Weatherbys. Since 1999, TBs have been permanently identified, at the time of registration, by means of an inserted microchip transponder. Blood-typing for pedigree analysis is also mandatory. Passports are issued by Weatherbys Ireland, which is the sole horse passport issuing organisation (HPIO) in Ireland (ROI and NI) for registering TBs for racing purposes. Updates on the number of TB horses in Ireland are published annually by Horse Racing Ireland (HRI) (Table 1; [25].

Table 1.

The numbers of stallions, mares, foals and horses in training registered with Weatherbys Ireland in the years 2002 to 2006

| 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stallions | 356 | 390 | 420 | 405 | 414 |

| Mares | 16,467 | 16,938 | 18,867 | 18,817 | 19,251 |

| Foals | 10,214 | 10,574 | 10,992 | 11,748 | 12,004 |

| Horses in training | 9,080 | 9,360 | 9,618 | 10,416 | 11,109 |

| Total | 36,117 | 37,262 | 39,897 | 41,386 | 42,778 |

Currently, it is not possible to obtain a complete profile (including the number, location or ownership) of TB horses in Ireland, because the following data are not available:

• The number of Thoroughbred horses exported and imported but not recorded: The rules of the International Agreement on Breeding and Racing [29] stipulate that HRI/Weatherbys should be notified if TB horses are moved abroad for racing or breeding; however, there is no such requirement to furnish a report if the movement is for any different purpose, or if movement is to the UK for whatever purpose;

• Thoroughbred foals and horses in the ROI or NI not registered with Weatherbys Ireland: These may either be unregistered or registered without a TB pedigree with an alternate Irish or UK HPIO. This latter registration would satisfy legislative requirements on equine identification but preclude the animals being used for racing purposes;

• Thoroughbred yearlings: The number of TB foals registered in 2005 is recorded (11,574) but not their place of residence at any given time;

• Point-to-point race horses: These animals are not included within the HRI's 'Horses in training' category. Furthermore, no other data on the numbers and location of these animals is available;

• Thoroughbreds in 'pre-training': TB horses, destined for a race-related activity, two years of age or older, but not returned as being in training or at stud; and,

• The actual number of horses that die or are slaughtered: The number of TBs reported to Weatherbys as having died in 2005, 2006 and 2007 were 1,213, 1,832 and 1,911, respectively. Reporting is on the basis of owner declaration, not surrender of identification documents in all cases.

The sports/leisure sector

In contrast to the racing sector, identification systems within the sports/leisure sector are less complete. Systems are run on an owner application basis by several HPIOs, licensed by DAFF, including:

• Weatherby's Ireland Ltd;

• The Irish Horse Board Co-operative Society (including the Irish Draught Horse Society);

• The Irish Pony Society Ltd;

• The Irish Cob Society;

• The Kerry Bog Pony Co-operative Society Ltd;

• The Connemara Breed Society; and,

• The Irish Horse Passport Agency.

Pedigree details are recorded, blood-typing performed and microchip transponders inserted if the HPIO is acting as the keeper of a stud-book. There is currently no central database of recorded microchip numbers, though some may share information on an informal basis. For non-pedigree animals, there is no common policy on permanent marking and no cross-referencing of information. Organisations or groups that are not HPIOs may use further separate batches of microchips for other identification purposes, for example to record previous presence in a horse pound or by a local authority to monitor the horse population in an area. Irish horses may carry none, one, or more than one functioning or nonfunctioning microchip device.

Irish horses may be identified by means of registration documents issued in another jurisdiction. For example, members of the Show Jumping Association of Ireland (SJAI) (recently renamed Showjumping Ireland) can secure UK passports for horses via the Ulster Region of the SJAI, an approved UK HPIO. The Horse Board of NI is a registered UK HPIO. The Donkey Sanctuary in Ireland sources passports and microchips for Irish donkeys from the Donkey Breed Society (a HPIO in the UK). UK HPIOs, under licence by DEFRA, can appoint 'competent persons' other than veterinary practitioners to complete the identification requirements for passport application, and the rules of some UK HPIOs even allow the owner of the animal, rather than an appointed 'competent person', to complete the silhouette, providing that a microchip transponder device has been previously inserted [14].

Few estimates are available of the total horse population within the sports/leisure sector. In a questionnaire of registered Irish Horse Board breeders (ISHQ) performed as part of a sports horse industry report, 8% admitted owning unregistered mares, although this figure was considered likely to be a sizeable underestimate [22]. These authors made calculations based on Central Statistics Office (CSO) figures and responses from the ISHQ and estimated a conservative national figure of 110,000 sport horses. Census figures from the CSO provided a farm ownership based measure of the equine population. Respondents to the ISHQ indicated if their sport horses were included in the CSO census data collection; regional and total sport horse herd populations were then calculated.

Legislation

Identification and horse movements

Since 2004, it has been a requirement under Irish national law (the European Communities [Stud-book and Competition] Regulations 2004) for horses to be accompanied by identification documents when moved. A 'move' is defined here as any movement out of a holding or other place, including movement between premises, entering competitions, for the purpose of breeding, being sold or being presented for slaughter. The legislation is specific to the movement of horses, and thus does not require the identification of horses kept permanently in one location. In July 2007, this was amended to read: "A person shall not move onto or from a premises, enter for a show, competition, race or other cultural event, sell, supply, acquire, export, present for slaughter or slaughter a horse ... unless it is accompanied by an identification document" (European Communities [Equine Stud-book and Competition, amendment] Regulations 2007). The power to stop, search and seize vehicles and horses where breaches of this legislation are suspected has now been enacted by the Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Foods. As per the European Communities (Equine Stud-book and Competition) Regulations of 2004, it is an offence to possess more than one identification document for a horse.

Disease notification

In 2006, consequent upon an outbreak of equine infectious anaemia in Ireland, the existing provisions relating to the notification and control of animal diseases contained in the Diseases of Animals Act of 1966 were consolidated and modernised (Diseases of Animals Act 1966 (Notification and Control of Animal Diseases) Order 2006). In brief, this requires that those in control of animals they suspect of being affected with the named diseases notify the relevant veterinary authorities and duly comply with instructions and restrictions that may be legally imposed. Of most immediate relevance to horses, African horse sickness (AHS) and West Nile Virus (WNV) are insect-transmitted viral diseases that are increasingly likely to spread here due to the increased transport of horses and equine products, the blurring of international borders and climate change. AHS has been identified in the horse population in Spain and WNV antibodies in birds in the UK [16].

Medical treatment of horses

For horses, EU animal remedies legislation is predicated on identification of the animal and its status as 'for human food production' (the default setting) or not so intended. Under national legislation, when the owner or keeper of a horse does not provide an identity document to a veterinary surgeon when requesting treatment, the veterinary surgeon may not administer any, except where the health or welfare of the horse is at risk (European Communities [Equine Stud-book and Competition] Regulations 2004). Where this condition is satisfied, the veterinary surgeon is authorised only to administer medicines listed in annexes I, II and III of EU Regulation 2377/90/EEC: these have an agreed maximum residue level (MRL) rendering them suitable for use in food producing horses. This precludes the use, in unidentified horses, of medicines under the cascade system (veterinary medicines licensed in other species or human pharmaceuticals), medicines in Annex IV of 2377/90/EEC (no MRL for horses), medicines specifically licensed for non-food producing horses (for example phenylbutazone) or medicines on the EU Essential Substances List for horses (EU Regulation 1950/2006). The Heads of Veterinary Medicines Agencies (HMA-V) in the EU commissioned a report on the (lack of) availability of veterinary medicines within member states [44] highlighting increasing concern for animal health and welfare as well as consumer safety from a dearth of authorised medicines.

Legal ownership and responsibility

Ownership of horses is currently recorded on a voluntary basis at registration and this does not confer legal title or impose legal responsibility in the context of any duty of care toward the animal. All owners, in the case of syndicates for example, may not be recorded. The lack of identification, traceability and legal linkage between a horse and a responsible person is considered to be an important industry issue [48]. A Commission Regulation (No 504/2008) has been agreed to implement Council Directives 90/426/EEC and 909/427/EEC as regards methods for the identification of equidae. This legislation makes it a requirement for all horses born or released for free circulation within member states (excepting designated populations of feral animals) to be identified, documented and registered by December 2009. In addition, it will confer legal responsibility on an identified keeper, who may be an owner of a horse, to ensure that proper identification of that animal is performed.

Transport

Since January 2007, commercial journey times and conditions have been governed by EU Transport of Horses Regulations as implemented by the European Communities (Animal Transport and Control Post) Regulations 2006 Statutory Instrument No. 675 of 2006. The transport of animals directly to or from veterinary practices or clinics, under the advice of a veterinarian, and the transport of animals to or from events by owners are excluded from the provisions of the Regulation. The Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food have issued guidelines for industry concerning the transport of horses and related operations [12].

In additional to statutory instruments on road transportation of horses, trade organisations also provide guidelines to their members. For example, the International Air Transport Association provides specifications for the transport of animals by IATA-affiliated aircraft [28].

Similarly, the Animal Transportation Association provides its members with best practice guidelines [1]. Monitoring of the long distance transport of horses and compliance with EU Council Regulation 1/2006 on the protection of animals during transport has also been carried out on a covert basis and reported [3].

The transport of horses between Ireland, the UK and France is subject to a tripartite trade agreement, as permitted by EU Council Directive 90/426/EEC, which permits free movement without health certification [10]. There is no centralised database recording the movement of horses between the Tripartite Agreement states. Other countries taking direct imports from Ireland may impose health certification requirements on Irish exporters. Irish horses subsequently registered, or re-registered, in the UK or France may move out of the Tripartite Agreement zone without reference to Irish law.

Removal of horses from population in ireland

Overview

It is an offence to slaughter or present a horse for slaughter unless it is accompanied by a lawful identification document (European Communities [Equine Stud-book and Competition, amendment] Regulations 2007).

Horses may legally be removed from the live population in Ireland by disposal through:

• Slaughter at approved meat export plants;

• Slaughter and disposal via Category 2 knackeries, licensed sub-contractors and approved veterinary pathology laboratories;

• Death, or euthanasia, and burial; or,

• Export.

Slaughter at approved meat export plants

There are currently only two approved meat export plants on the island of Ireland (one in the ROI and one in NI) licensed to supply horse meat for human consumption. In the ROI, licensed slaughter plants must only take horses which have valid identification documents (European Communities [Equine Stud-book and Competition, amendment] Regulations, 2007) issued at least six months previously (European Communities [Equine Stud-book and Competition] Regulations, 2004). These documents must be surrendered to the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (DAFF) at the time of slaughter. The total numbers for horses slaughtered annually from 2002 to 2007 in the one remaining ROI plant are summarised in Table 2. The licensed NI plant, which possesses a UK HPIO licence, has not shown returns for any horses slaughtered for human consumption since March 2006.

Table 2.

The total number of horses slaughtered in Ireland between 2002 and 2007 in the sole remaining licensed horse slaughter plant in the ROI

| Year | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of horses slaughtered | 1,995 | 2,060 | 824 | 614 | 822 | 1,486 |

Slaughter and disposal via Category 2 knackeries, licensed sub-contractors and approved veterinary pathology laboratories

In the ROI, Category 2 knackeries are licensed to collect horse carcases not for human consumption either directly or indirectly via licensed sub-contractors. They are not currently required to submit records of the numbers of horses disposed of. A voluntary submission scheme was commenced in 2007.

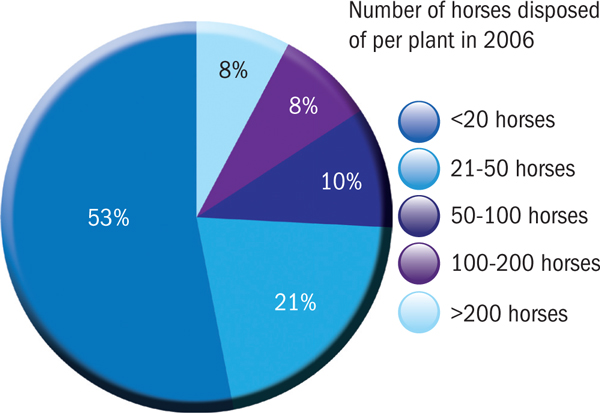

As part of the research for this paper, a telephone survey of the 39 Category 2 plants and approved sub-contractors was conducted in September 2007. On average, 51 horses were reported as collected or processed at Category 2 plants and licensed subcontractors in Ireland. The total estimated number processed by this means was 1,975 horses. More than half (53%) of the plants processed fewer than 20 horses in that period (Figure 1). Horses are also disposed of by the State Veterinary Service and the Irish Equine Centre (Table 3). It should be noted that there is some overlap between these disposals and those of Category 2 Plants, as some of the horse carcases disposed of via veterinary laboratories have been delivered to them by Category 2 operators.

Figure 1.

The number of horses disposed of by Category 2 plants in the ROI during 2006.

Table 3.

The number of horses recorded as being disposed of through registered veterinary laboratories (the State Veterinary Service and the Irish Equine Centre) during 2006

| Organisation | Horses | Foetuses/neonates |

|---|---|---|

| State Veterinary Service | 68 | 20 |

| Irish Equine Centre | 260 | 390 |

Death, or euthanasia, and burial

Statutory Instrument No. 612 of 2006 sets out the national legislation incorporating the provisions of EC Regulation 1774 of 2002. Pet animals, defined as 'any animal belonging to species normally nourished and kept, but not consumed, by humans for purposes other than farming', may be disposed of by the granting of a licence.

Total numbers of horses disposed of within Ireland

Without allowing for the overlap between State Laboratories and Category 2 knackeries, the total number of horses disposed of by the stated licensed routes in 2006 was 3,207. This compares with a registration number for TB foals alone, for the same period, of 12,004.

Exports

As previously mentioned, there is no comprehensive system of recording of the movement of horses within the Tripartite Agreement area. Point-of-exit checks are carried out by veterinary inspectors of health certified horses (required for direct export to non-tripartite countries) and random inspections of tripartite horses: the numbers recorded for the years 2001 to 2005 are detailed in Table 4[10].

Table 4.

The numbers of horses exported from Ireland for which there are records in the years 2001 to 2005

| 2001 | 4,764 |

| 2002 | 2,837 |

| 2003 | 2,588 |

| 2004 | 2,025 |

| 2005 | 1,917 |

Governance of the irish equine industry

The racing sector

Thoroughbred racing on the island of Ireland is governed by HRI and the Racing Regulatory Body. Their functions are established by statute - the Irish Horse Industry Act 1994 and the Horse and Greyhound Racing Act 2001. HRI regulates and controls the financial and business aspects of racing. It encourages new racehorse ownership groups to emerge by means of promoting syndication. HRI supports the provision of racing prize money, the activities of the Racing Regulatory Body, the Irish Equine Centre, Irish Thoroughbred Marketing, the Irish Farriery Authority, the Irish TB Breeders Association, the Race Academy and Centre of Education (RACE) and a racehorse retraining scheme, run by the Irish Horse Welfare Trust (IHWT charity no. 14634).

The Racing Regulatory Body comprises the Turf Club and the Irish National Hunt Steeplechase Committee. It is charged with administering the rules of racing, upholding the integrity of the sport, and safeguarding the health and welfare of participants. The Racing Regulatory Body licences key personnel in racing who must complete courses of education at RACE. The Racing Regulatory Bodies Inspector of Course inspects racecourses and point-to-point tracks in advance of racing to confirm safety for horse and rider; a Turf Club official then attends each event and furnishes a report to the Turf Club Office. A veterinary statistical report is submitted annually, and a full review of safety, primarily aimed at addressing the issue of safety for human participants in racing, was last conducted in 2004 [47].

In terms of horse welfare, the number of falls per race varied with the type of sport (Table 5). In general, horses in point-to-point racing have a substantially higher rate of falls than in either flat or national hunt racing. The Turf Club Safety Review [47] reported a reduction in jockey falls per point-to-point race from over 15% to less than 10% between 2000 and 2003. It did not detail how closely jockey falls correlated with horse falls.

Table 5.

The fall rate, in percent, per jockey ride during 2000 to 2003, by race type in Irish Thoroughbred racing

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flat | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.26% |

| National hunt | 5.3% | 4.5% | 5.0% | 4.9% |

| Point-to-point | 15.1% | 16.2% | 13.4% | 9.5% |

The Irish Equine Centre (a registered charity) acts as a sentinel for the equine industries and provides a repository of expertise and data on disease issues. It also has a stated aim to conduct research on the incidence, causes, prevention and treatment of equine disease [31]. In the UK, this type of research is coming under increasing scrutiny by animal rights organisations [2], with increasing emphasis on funding sources and whether benefit accrues to horses in terms of improved health and welfare standards rather than solely to those who would use them for profit or sport.

Irish Thoroughbred Marketing is directed by HRI to promote the sale of Irish TB horses, especially abroad. It encourages foreign investors to purchase TBs by means of promotional events and financial support. The Inward Buyers Programme, which was introduced in July 1996, refunds part or all of overseas horse purchasers' travel costs.

The Irish Farriery Authority conducts courses of education and training for farriers and maintains the Irish Farriery Register, which has an open door policy regarding inclusion [32]. The practice of farriery is not controlled under statute in Ireland.

The Irish TB Breeders Association (ITBA) is the representative organisation for breeders of Thoroughbred horses in Ireland. It provides education, support, advice and training for members, helps to direct the work of bodies such as HRI and the Irish Equine Centre, and represents the interests of breeders both in the national forum and internationally via the European Federation of Thoroughbred Breeders' Association. The Race Academy and Centre for Education (RACE) is the Irish racing industry's training centre for those seeking a HRI-licensed career within racing, as well as for those seeking more general racing education and guidance. A racehorse retraining scheme, run by the Irish Horse Welfare Trust (IHWT) is funded by HRI with current funding of €63,000 for 2007. An additional capital grant of €144,000 in 2008 has been promised toward the development of purpose-built facilities with the aim of at least a doubling of the numbers of racehorses retrained from a current base of approximately 15 [39].

The sports/leisure sector

On November 8, 2006, the Minister for Arts, Sport and Tourism announced the establishment of a new agency for equestrianism in the form of a limited company, horse Sport Ireland [15]. This followed a report prepared by a former Secretary General of the Department of Agriculture and Food, which recommended new governance structures for the sports and leisure equestrian sectors.

Horse Sport Ireland (HSI) is to co-ordinate standards and communication between the many organisations that have traditionally represented smaller equine industry sectors. The board of directors of HSI comprises an independent chairman; eight directors representing Federation Equestre Internationale (FEI) disciplines, eg., Eventing Ireland, the Show Jumping Association of Ireland (SJAI) and Dressage Ireland; four directors representing other sport/leisure organisations, for example the Irish Pony Club, the Association of Irish Riding Establishments (AIRE), the Association of Irish Riding Clubs (AIRC) and the Irish Pony Society; and five directors representing breeding. HSI formally adopted the largest of the sports horse breeding organisations (The Irish Horse Board) on January 1, 2008.

State funding of the equine industries

The racing sector

Horse Racing Ireland receives state funding via the Horse and Greyhound Racing Fund as well as from internal industry sources such as:

• The returns from betting - the betting levy;

• The breeding of Thoroughbred horses - the statutory foal levy;

• The licensing of participants - registry office income; and,

• Sponsorship/contributions from supporters

Between 2001 and 2006, €317 million of state support has been provided and the government is committed to a similar level of funding until 2008 [18]. During this period, the level of current (as distinct from capital) funding has been greater than the combined funding for more than 60 other sports bodies supported by the Department of Arts, Sport and Tourism and Irish Sports Council [18]. The contribution of the Horse and Greyhound Fund to HRI's income for 2006 was €56,045, an increase of €1.4 million or 2.5% over the previous year [24].

Funding and the sports/leisure sectors

At the inception of Horse Sport Ireland, an additional €1.75 million was allocated by the Department of Arts, Sports and Tourism to fund its establishment and its role in governing equestrian activity in the sports and leisure horse sectors [41]. In 2007, its actual allocation of state support was of the order of €1.85 million from the Department of Arts, Sport and Tourism, €1.6 million from the DAFF and €1.1 million from the National Development Plan (NDP). As per Irish Thoroughbred Marketing, the breeding wing of HSI (the Irish Horse Board) partakes in the Inward Buyers Programme to promote sales of Irish horses abroad.

Education and training

General

The bodies which provide information or teaching on equine health and welfare can be divided into two distinct groupings: those focusing on improving performance by some measurable criterion, and those with a primary remit to improve welfare standards for horses.

Education and training aimed at improving performance

A range of education and training programmes are available for members of the equine industry. The programmes are designed to fulfil different needs corresponding to the different sectors; success may be measured in terms of economic, social or athletic achievement. As examples, RACE serves the racing industries needs for training and education; Teagasc, a government body, is tasked with improving education standards for those involved in the farming industries; the University of Limerick and University College Dublin provide third level courses in equine science; and the Association of Irish Riding Establishments (AIRE) conduct training courses in conjunction with FAS, another government education and training agency. Charitable groups are also involved in this work: for example, the Festina Lente Foundation, Riding for the Disabled-Ireland, the Cherry Orchard Project, Fettercarne Tallaght Project and Pavee Point's Horsemen Project. These aim to promote human social welfare through an improved quality of interaction with horses.

Improving standards of horse welfare is an aim that takes second place to improving human returns; financial rewards, personal achievement, competition successes. Nevertheless, these groups play an important role in communicating the value of improved standards to groups of horse owners and riders.

Education and training with a primary focus on equine welfare

Education focused on equine health and welfare is provided by third level institutions, as described above. Charities such as the Irish Horse Welfare Trust (IHWT), the Irish Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ISPCA), Regional SPCAs, the Blue Cross and the Donkey Sanctuary also provide training to support best practice and promote better standards of equine health and welfare. On December 13, 2006 the Minister for Agriculture and Food announced grants of €1.2 million for animal welfare bodies countrywide to assist in their work in 2007 [11]. On December 14, 2007, the Minister announced an increase in funding to animal welfare charities of 25% (€1.46 million for 2008) and an increase in the number of welfare bodies funded by 13 to 107 [13].

Animal welfare

Introduction

The welfare of animals is broadly considered in three disciplines:

1 Animal welfare science, which studies the effects of environment, human interaction, and husbandry procedures on behaviour, productivity, physiology and indices of clinical health on animals. With reference to horses, the advent of a new subset 'equitation science' is noteworthy [34];

2 Animal welfare law: The first laws on animal welfare were based on cruelty to animals. On a philosophical level, legal requirements are changing towards a duty of care to be imposed on animal keepers/owners; and,

3 Animal ethics, which considers the acceptability of the use of animals in different contexts.

There are a multitude of definitions of animal welfare with no one gaining universal acceptance. In common usage is a definition by Broom [6] which describes welfare as an individual animal's state as regards attempts to cope with its environment. Some authors advocate defining welfare by focusing on animal needs rather than human perceptions [51].

Guidelines on animal needs, and the responsibilities of animal keepers, are contained in the 'Five Freedoms'. These are now generally accepted as the standards to benchmark animal welfare. They have been adopted at national e.g.,)[19], European [17,20] and global levels [43]. For domesticated horses, the Five Freedoms can be described as follows [38]:

1. Freedom from hunger, thirst and malnutrition: This requires a supply of fresh, clean water, an appropriate diet to attain and maintain health and vigour, and the use of appropriate management practices to allow these resources to be correctly utilised.

2. Freedom from thermal and physical discomfort: This requires that horses have sufficient bedding and shelter to insulate them against adverse climatic conditions. However, the provision of adequate ventilation is essential for respiratory health; rugs and blankets offer a better solution to issues of thermal comfort than a reduction in the quality of ventilation.

3. Freedom from pain, injury and disease: These should be prevented, where preventable, and otherwise there should be rapid diagnosis and treatment of injury, infections, infestations and disease. The increased risk of injury between horses in unstable groups must be balanced against a need for social contact. Imposed 'non-natural' feeding patterns may lead to physical disease, for example gastric ulceration.

4. Freedom to express normal patterns of behaviour: Horses are sociable animals, they should have the company of other animals, preferably horses, and be kept in situations that foster normal behaviour patterns. Imposed confinement and 'non-natural' feeding patterns may lead to repetitive, non-function behaviour patterns such as stereotypies.

5. Freedom from fear and distress: Horses should not be subjected to prolonged periods where they experience significant psychological stress. Management practices such as the keeping of horses in unstable social groups potentially inflict an ongoing fear of aggression.

Equine welfare and the human-horse relationship

People can enhance or diminish the standard of welfare for horses with which they interact: people affect the provision of horses' needs as laid out by the Five Freedoms. The value placed by a person on a horse's welfare will depend on the type and intensity of the human-horse relationship, and how the personal costs of ownership are balanced against the perceived benefits [46]. The human perception of animal welfare is undoubtedly affected by what the animal is used for [52] and thus, the more valued the animal is, the more likely that the human influence will tend to improve the welfare standard. Where animals are valued primarily in an economic context there can be an inherent conflict between animal welfare (as perceived by humans) and livestock productivity (as pursued by increasingly 'intensive' methods of production) [37]. Another method of grading an animal's value to us is to place it on a sociozoologic scale, where 'good' animals rank highly as pets or companions; those with some extrinsic value to us occupy middle ranking as tools; and pests, vermin and others considered to represent a nuisance or threat are assigned the lowest status (Table 6) [4].

Table 6.

The status of animals when categorised according to a sociozoologic scale, from Arluke and Sanders, Regarding Animals, 1996, Templar University Press

| Status | Category of animal |

|---|---|

| Friends | Companion animals hobby animals horses |

| Tools | Food producing animals laboratory animals |

| Foes | Vermin predators |

Equine welfare internationally

There has been increasing interest in the subject of equine welfare. Until relatively recently, however, little research was directed at investigating welfare standards for domesticated horses [50]. Research emphasis has been on investigating the effects of environment and management practices on patterns of behaviour and the development of abnormal behaviours such as stereotypies. For example, a lower incidence of aberrant behaviour (which has been equated with better welfare) has been identified in paddock reared, group-housed weanlings as compared to a cohort weaned in individual stalls [21]. Studies have been conducted on the prevalence of stereotypic behaviour patterns in TB horses [49,5,45] and in dressage, eventing and endurance horses [35]. A compensatory increase in the intensity and rate at which an unwanted stereotypic behaviour may be displayed post behaviour inhibition has been noted [36]. This has implications for equine welfare. The study of equine learning behaviour and training methods has proved fruitful with important conclusions about how to develop appropriate and effective training methods for equitation purposes [34] and when retraining horses in rescue and re-homing projects [30].

Equine welfare in an Irish context

Animal welfare science is a poorly funded research discipline in Ireland. This is especially the case with equine welfare, reflected by the small number of peer-reviewed publications (e.g.,) [9]. In spite of the limited framework supporting horse welfare in Ireland, the horse industries understand that they have a general responsibility to ensure the health and welfare of horses they use. It is also vital to the organising bodies that the general public are convinced that the training, competition and management practices used are not in any way abusive [22]. In a report commissioned by the Irish Horse Board, these authors identified areas in which standards may be compromised and listed recommendations for the safeguarding of equine welfare. Horse Sport Ireland has appointed a training and education manager who will have responsibility for co-ordinating this approach to improving welfare standards [27]. Comprehensive animal welfare guidelines for horses, donkeys and ponies in Ireland have been developed by an advisory council to the Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food [19]. Currently, the legislative standard for animal welfare in the ROI is that as set down in the UK Protection of Animals Act of 1911, although in more recent years, regulations have emanated from the EU establishing a framework of legal provisions concerning food producing species and animals used in research. In 2008, equines (excepting while being used in competitions, shows, cultural and sporting events) were brought within the scope of EU legislation designed to protect the welfare of farmed animals (Statutory Instrument 14 of 2008) obliging a person to ensure that an animal under their care is not caused unnecessary pain, suffering or injury.

The Minister for the Environment and Green Party TD, John Gormley, has stated that animal welfare and the legal protection of animals are the responsibility of the Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food: "The programme for government includes a commitment that a comprehensive animal welfare bill will be introduced, updating existing legislation to ensure that the welfare of animals is properly protected and that the penalties for offenders are increased significantly" [42]. At the time of writing, there is a Government-sponsored animal health and welfare bill in the drafting stage. The Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food has announced that there will be proper provision for the protection of animal welfare and increased penalties for offenders [33]. Once enacted, this national legislation is likely to determine the standard of protection that animals, including horses, in Ireland can expect for some time to come.

Discussion

-There are a number of fundamental issues that adversely compromise the health and welfare status of horses in Ireland. Each is underpinned by concerns relating to equine identification and the registration of ownership. It is not currently possible to track horses from birth to death, except those whose owners/keepers voluntarily register their origin, change of ownership, movement and ultimate demise. There is no legally enforced system of mandatory registration of horses, their place of keeping or their ownership. The export and import of horses are not effectively monitored. With at least 8% of members of a large sports horse breeders' co-operative admitting keeping unregistered mares, it is highly likely that others, who are not members of any equestrian organisation or registered with the CSO as farm-owners, will possess unregistered horses in even greater percentages [22]. Issues that depend on a coherent and comprehensive system cannot be legally enforced. There has been little formal study or discussion of these further issues to-date. The chief executive of Horse Racing Ireland has warned that "horses were currently being produced for which there would be no races" [26]. There must be evidence-based research to provide objective data on the numbers, types, suitability, uses and endpoints of horses produced.

Disposal of horses

The number of horses being processed for the human food chain, taken in combination with the number being disposed of legally via the registered knackery system and veterinary laboratories, is at variance with the numbers of horses being produced. Excepting those horses processed by the sole licensed horse slaughter facility, there is no system of recording when horses leave the population by death or transport abroad. Many are falling through the gaps in the industry structures, and being unaccounted for, which represents a real or potential threat to equine welfare. For example, it is commonly held that licences are not sought for the disposal of horses by burial in remote areas.

Disease surveillance

An outbreak of equine infectious anaemia in the horse population in Ireland in 2006 has served as a wake-up call to the government and the equine industries about how ill-prepared we might be if a more contagious disease entered our immunologically naïve population of horses. AHS and WNV may represent such threats to our equine population and to our equine industries [16].

Both can cause high morbidity and mortality rates in susceptible populations, raising serious welfare concerns for our horse population, were we unable, due to lack of a rigorous identification and tracing system for horses, to contain an outbreak.

Medicines use

Animal remedies regulations depend, for their implementation regarding horses, on a reliable system of identification of equidae. Horses are classified in EU legislation as a 'food-producing animal' unless otherwise specifically declared by the owner. The financial turnover of the veterinary medicines market is reported to be only 3-5% of the pharmaceutical market, with more than 50% of the market involving the agriculture sector and profit margins smaller than in the human sector [44]. As the market in licensed veterinary medicinal products progressively contracts due to the cost of the licensing procedure (particularly a problem when studying medicines for equidae) and the relatively small available market, the importance of innovative, non-equine licensed veterinary and human remedies becomes ever greater for safeguarding equine welfare. These non-equine licensed medicines must be used under the cascade system for non-food producing species with a requirement to permanently exclude the horse from the human food chain. This process relies on an ability to accurately identify the animal being treated, but encourages non-compliance with identification legislation due to the cost of disposal of non-food designated horses.

Legal responsibility for owning and keeping horses

Currently the registered owner of an animal is not necessarily the legal owner, this has been based on owner self-certification at the time of registration. There is no legal responsibility to correctly register ownership or any subsequent change. An unknown number of horses remain unregistered. This presents serious legal difficulties when it becomes necessary to conduct a prosecution under animal welfare legislation. Showing a case proven without being able to correctly lay responsibility is a Pyrrhic victory at best.

Transport

EU transport of animals regulations, as applied to equidae, which were implemented in 2007, were motivated by a desire to pressurise those engaged in the long-distance transport of horses for slaughter sufficiently so as to render this trade uneconomic. The work of groups such as Animals' Angels and the International League for the Protection of Horses (ILPH) in this regard continues. There is, however, increasing disquiet among the commercial horse transport sector that their ability to trade in non-slaughter horses has been unduly compromised. The increased requirements for driver training and certification, partitioning of horses, lodging of travel plans and satellite tracking of vehicles has undoubtedly introduced an additional layer of bureaucracy and cost.

Governance and funding

In the racing sector, the regulatory body (Racing Regulatory Authority) charged with safeguarding the welfare of the human and animal participants is funded by the body (HRI) that directs the financial and business activities of the sport. Mr Michael Smurfit alluded to turmoil in the financial world generally, adding that, "It could well have a significant adverse effect on the Government's income and it could mean increased scrutiny for the present large subsidies that our industry has recently enjoyed" [40]. In the sports/leisure sectors, a new body (Horse Sport Ireland) has been set up with state support to direct the organisations, which individually monitor the many equestrian sports and leisure activities. Its progress is being watched with great interest as it promises to bring coherence to a previously seriously fragmented industry.

Training and education

At present, there is no integrated structure for the dissemination of information relating to horses or the equine industries. State-sponsored programmes work alongside private programmes focused on members of individual organisations; the teaching of equine welfare as part of the course content is not mandatory. How and when horse owners and keepers learn about equine health and welfare, and the quality of that learning, seems critical in any attempt to improve accepted industry standards. The Pony Club, for example, is often the first point of contact for young people (and their parents) with the concept of a responsibility for horse care, and thus it represents an ideal opportunity for education and guidance [8]. The practice of farriery, with real potential for adverse welfare effects, remains unregulated by statute and thus training is of a voluntary and non-standardised nature. Similarly, the provision of para-veterinary services such as physical therapies and dental treatments by non-veterinarians has not been subject to direct legislative control in Ireland to date, and only indirectly where such might be deemed to fall outside of the provisions of the Veterinary Practice Act 2005. Charitable groups compete for government aid, as for private support. There is no unifying voice to act as a conduit for financial support, a central point of advocacy for animal welfare and education for those involved with horses.

Conclusion

Horses are hugely valuable to Ireland on several levels - economic, social and individual. The success of industry sectors in positioning Ireland as a global force in the racing and sports horse business cannot be overestimated. Socially, culturally and traditionally horses have been interwoven with Irish society at a fundamental level. Similarly, the risks to Ireland's equine industries from a failure to appreciate the threats to equine health and welfare cannot be ignored. There are current and potential future problems with the horses themselves. The issue which underpins these threats is that of identification of horses, and the registration of horse ownership. The lack of a comprehensive integrated system of horse identification, and thus the other issues identified in this paper which depend on it, fundamentally links current concerns for equine welfare. Research into these links is required, the findings should be disseminated appropriately so that those who are responsible for developing policy, those who manage the financial resources available to the equine industries, and those who are directly responsible for the horses themselves can be appropriately educated and the findings translated into actions that will nullify the threats, and achieve real improvements in equine health and welfare.

Relevant legislation

a. Irish legislation

Diseases of Animals Act 1966 (Notification and Control of Animal Diseases) Order (2006). SI 359 of 2006. Dublin, DAFF.

European Communities (Animal transport and control post) Regulations (2006). SI 675 of 2006. Dublin, DAF.

European Communities (Equine stud-book and competition) Regulations (2004). SI 399 of 2004. Dublin, DAF.

European Communities (Equine stud-book and competition) (amendment) Regulations (2007). SI 530 of 2007. Dublin, DAFF.

European Communities (Welfare of farmed animals) Regulations (2008). SI 14 of 2008. Dublin, DAFF.

Veterinary Practice Act 2005. Number 22 of 2005. Dublin, DAF.

b. European legislation

Commission Regulation (EC) No 504/2008 of 6 June 2008 implementing Council Directives 90/426/EEC and 90/427/EEC as regards methods for the identification of equidae. IN: Official Journal of the European Communities L149, 3-32. June 7, 2008.

References

- AATA. Animal Transport Association manual for the transport of live animals. 2. 2007. http://www.aata-animaltransport.org/ [Accessed 22 December 2007] [Google Scholar]

- Animal Aid. Animal Aid. Tonbridge, Kent, UK; 2007. A Dead Cert: Vivisection and the horse racing industry.http://www.animalaid.org.uk/images/pdf/booklets/deadcert.pdf [Accessed 22 December 2007] [Google Scholar]

- Animals' Angels. Enforcement of Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2005 on the protection of animals during transport. Frankfurt, Germany, Animal's Angels; 2007. Transport of horses requirement for "Individual stalls" for long journeys. [Google Scholar]

- Arluke A, Sanders C. Regarding Animals (Animals, Culture and Society) Philadelphia, Temple University Press; 1996. pp. 169–182. [Google Scholar]

- Borroni A, Canali E. In: Proceedings of the 26th Congress of Applied Ethology. Nichelmann M, Wierenga H, Braun S, et al, editor. 1993. Behavioural problems in Thoroughbred horses reared in Italy; pp. 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Broom DM. Indicators of poor welfare. British Vet Jounal. 1986;142:524–526. doi: 10.1016/0007-1935(86)90109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broom DM. Quality of life means welfare: how is it related to other concepts and assessed? Animal Welfare. 2007;16(S):45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley P, Dunn T, More SJ. Owners' perceptions of the health and performance of Pony Club horses in Australia. Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 2004;63:121–133. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll NP. Stereotypies in Irish thoroughbred horses in race training. MSc thesis, Department of Life Sciences, University of Limerick. 2002.

- Coughlan M. Dail Eireann. Written answers - live exports of horses. 2006. http://historical-debates. oireachtas.ie/D/0625/D.0625.200610170109.html [Accessed 22 December 2007]

- DAF. Minister Coughlan announces grants of €1.2 m for animal welfare bodies countrywide. 2006. http://www.agriculture.gov.ie/index. jsp?file=pressrel/2006/244-2006.xml [Accessed 22 October 2007]

- DAFF. Guidelines for Council Regulation (EC) no. 1 of 2005 of 22 December 2004 on the protection of animals during transport and related operations concerning the transport of horses. Dublin, DAFF; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- DAFF. Minister Coughlan announces 25% increase in funding for animal welfare organisations. 2007. http://www.agriculture.gov.ie/index. jsp?file=pressrel/2007/263-2007.xml [Accessed 18 December 2007]

- Defra. Livestock movements, identification and tracing: horse passports - questions and answers. 2008. http://www.defra.gov.uk/animalh/id-move/horses/horses_qa.htm#4 [Accessed 18 January 2008]

- Department Of Arts Sports & Tourism. Establishment of Horse Sport Ireland. Dept of Arts, Sport & Tourism. 2006. http://www.dast.gov.ie/publications/release. asp?ID = 1707 [Accessed 21 October 2007]

- Duggan V. Exotic viral diseases and the current threat to the Irish equine population. Irish Veterinary Journal. 2008;61:116–121. [Google Scholar]

- EU Commission. Animal welfare. 2007. http://ec.europa.eu/food/animal/welfare/index_en.htm [Accessed 21 November 2007]

- Fahey T, Delaney L. Budget Perspectives 2007. Dublin,The Economic and Social Research Institution; 2006. State financial support for horse racing in Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- FAWAC. Animal welfare guidelines for horses, donkeys and ponies. In: Farm Animal Welfare Advisory Council, editor. Dublin. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Federation of Veterinarians of Europe. Stable to table. 2007. http://www.fve.org/papers/pdf/fhph/position_papers/stabletotable.pdf [Accessed 21 November 2007]

- Heleski CR, Shelle AC, Nielsen BD. et al. Influence of housing on weanling horse behavior and subsequent welfare. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 2002;78:291–302. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1591(02)00108-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy K, Quinn K. The future of the Irish sport horse industry. University College Dublin, commissioned by the Irish Horse Board; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy KD, Quinn KM, Brophy PO. The importance of the Irish sport horse industry in the development of social capital within a changing rural Ireland. Agricultural Research Forum. 2007. http://www.agresearchforum. com/publicationsarf/2007/Page%20122.pdf [Accessed 20 December 2007]

- HRI. Annual report 2006. Horse Racing Ireland. 2006. http://www.goracing.ie/AssetLibrary/Files/HRI/Info/annualreport2006.pdf [Accessed 30 January 2008]

- HRI. Factbook. Horse Racing Ireland. 2006.

- HRI. Horse Racing Ireland issues 2007 industry statistics. 2008. http://www.goracing.ie/Content/hri/hrinews.aspx?id=5090 [Accessed 18 January 2008]

- HIS. Announcement of management positions. 2007. http://www.horsesportireland.ie/pressrelease.html [Accessed 21 October 2007]

- IATA. Live Animal Regulations, IATA, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. 2006. http://www.iata.org/ps/publications/lar.htm [Accessed 22 December 2007]

- IFHA. International agreement on breeding and racing. Pub International Federation of Horseracing Authorities. 2007. http://www.horseracingintfed.com/racingDisplay.asp?section=10 [Accessed 1 February 2008]

- Innes L, McBride S. Negative versus positive reinforcement: An evaluation of training strategies for rehabilitated horses. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 2008;112:357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2007.08.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Irish Equine Centre. 2007. http://www. irish-equine-centre.ie/research.htm [Accessed October 18 2007]

- Irish Farriery Registry. The Irish Farriery Authority. 2007. http://www.irishfarrieryauthority.com/IFRaboutus.htm [Accessed 18 October 2007]

- MacConnell S. Concern over animals abandoned after Christmas. The Irish Times. Dublin. 2007. p. 4.

- McGreevy PD. The advent of equitation science. The Veterinary Journal. 2007;74:492–500. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGreevy PD, French NP, Nicol CJ. The prevalence of abnormal behaviours in dressage, eventing and endurance horses in relation to stabling. The Veterinary Record. 1995;137:36–37. doi: 10.1136/vr.137.2.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGreevy PD, Nicol CJ. Physiological and behavioural consequences associated with short-term prevention of crib-biting in horses. Physiology and Behaviour. 1998;65:15–23. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(98)00070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInerney J. Defra Farm & Animal Health Economics Division. London; 2004. Animal welfare, economics and policy. [Google Scholar]

- Mills DS, Clarke A. In: The welfare of horses. Waran N, editor. The Netherlands, Springer/Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2007. Housing, management and welfare; pp. 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Morris J. Horse Racing Ireland provides grant of €144,000 to the Irish Horse Welfare Trust. Ireland's Horse Review. 2008.

- O'Connor B. The Irish Times. Dublin; 2007. Carbery in class of his own.http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/sport/2007/1203/1196375209804.html [Accessed 22 December 2007] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donoghue J. The Minister for Arts, Sport and Tourism at the launch of Horse Sport Ireland, 20/11/2006. 2006. http://www.arts-sport-tourism.gov.ie/publications/release.asp?ID = 1727 [Accessed 29 January 2008]

- O'Regan M. The Irish Times. Dublin; 2007. Gormley concerned over hunting of tame deer; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- OIE. Guidelines for animal welfare. Terrestrial animal health code. 2007. http://www.oie.int/eng/normes/mcode/en_titre_3.7.htm [Accessed 21 November 2007]

- Report of task force on availability of veterinary medicines. 2007. http://www.hma.eu/203.html [Accessed 28 January 2008]

- Redbo I, Redbo-Torstensson P, Odberg. et al. Factors affecting behavioural disturbances in race-horses. Animal Science. 1998;66:475–481. doi: 10.1017/S1357729800009644. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson I. The human-horse relationship: how much do we know? Equine Veterinary Journal Supplement. 1999;28:42–45. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1999.tb05155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turf Club Safety Review: report and recommendations. The Irish Turf Club. 2004. http://www.turfclub.ie/site/index.php?option=com_wrapper&Itemid = 39 [Accessed 28 January 2008]

- Turnbull SN, Abraham DM. Applying Equine Science: research into business. Cirencester, UK, BSAS; 2005. The public's opinion regarding the impact of equine passports on the industry. [Google Scholar]

- Vecchiotti GG, Galanti R. Evidence of heredity of cribbing, weaving and stall-walking in Thoroughbred horses. Livestock Production Science. 1986;14:91–95. doi: 10.1016/0301-6226(86)90098-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waran NK. The welfare of horses. The Netherlands, Springer/Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2007. p. ix. [Google Scholar]

- Webster AJF. Animal welfare limping towards Eden. Blackwell Science Ltd; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfsensohn S, Honess P. Laboratory animal, pet animal, farm animal, wild animal: which gets the best deal? Animal Welfare. 2007;16:117–123. [Google Scholar]