Abstract

INTRODUCTION

IBS traditionally has been classified by stooling pattern (e.g., diarrhea-predominant). However, other patterns of symptoms have long been recognized, e.g., pain severity. Our objective was to examine the utility of subtyping women with IBS based on pain/discomfort severity as well as predominant bowel pattern.

METHODS

Women (n=166) with IBS completed interviews, questionnaires, and kept a diary for 28 days. Rome II questionnaire items eliciting past 3-month recall of hard and loose stools, and frequency and severity of abdominal pain or discomfort were used to classify participants into six subtypes - three bowel pattern categories by two pain/discomfort severity categories. Concordance of these subtypes with corresponding diary items was examined. Analysis of variance tested the relationship of bowel pattern and pain categories to measures of quality of life and symptoms.

RESULTS

There is moderate congruence of retrospective classification of bowel pattern and pain/discomfort severity subtypes with prospectively reported stool frequency and consistency and pain severity. Quality of life, impact of IBS on work and daily activities, and cognitive beliefs about IBS differed significantly based on abdominal pain/discomfort category but not on predominant bowel pattern. There is evidence of an interaction, with the effect of pain severity being strong in the IBS-diarrhea and IBS-mixed groups but absent in the IBS-constipation group. Similar results hold for most diary symptoms, except for those directly related to bowel pattern.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall distress of abdominal pain/discomfort is more strongly related to severity of abdominal pain/discomfort than is the predominant stool pattern in patients with IBS. Categorizing IBS patients by abdominal pain/discomfort severity in conjunction with predominant bowel pattern may be useful to clinicians and researchers in developing more effective management.

INTRODUCTION

Functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorders (FGIDs), including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in adults, are among the most common and costly health care problems in the US [1]. IBS is diagnosed by the presence of abdominal pain or discomfort associated with bowel pattern changes and/or relieved by bowel movement, and patients usually suffer from diarrhea and/or constipation. Effective, targeted therapies for IBS are challenged by the clinical recognition that there is significant variability in the clinical presentation of patients with IBS and the fact that these symptoms can fluctuate over time. Patients differ by predominant stool type, severity and frequency of pain/discomfort, comorbidities including psychological distress and somatic complaints as well as gynecologic symptoms in women) [2].

The use of categories based on predominant bowel pattern (constipation-predominant, diarrhea-predominant, alternating or mixed; IBS-D, IBS-C, IBS-M, respectively) has received acceptance by most clinical investigators [3]. Indeed, this categorization commonly dictates pharmacological management. However, the influence of other symptoms such as pain/discomfort also may differentiate the response of patients to treatments. Yet, little attention has been paid to further differentiate these patients (beyond stooling pattern) according to other symptoms.

There is evidence that these other symptoms, particularly pain and discomfort, are relevant to subtyping IBS. In a prior study we noted that women with medically diagnosed IBS reported more abdominal pain/discomfort, bloating and intestinal gas than bowel pattern symptoms of constipation and diarrhea [4]. In this population the abdominal pain/discomfort symptoms was correlated more strongly with reductions in quality of life (QOL) and interference with work and school than bowel symptoms [4]. The contribution of symptom severity to the disease burden of IBS was recently addressed by Bond and colleagues [5] and has been further substantiated by the recent work of Spiegel [6].

The report of abdominal pain/discomfort is a fundamental symptom in the diagnosis of IBS using the ROME III criteria [7]. In our prior work, premenopausal women with IBS (Rome II criteria) reported moderate to severe abdominal pain on 37% of days in a 28-day diary [8]. While all 3 bowel pattern IBS subgroups (constipation, diarrhea, alternating) report abdominal pain/discomfort it is unknown whether the severity of abdominal pain/discomfort is similar across bowel pattern subgroups or whether it is equally associated with reductions in quality of life, increases in psychological distress and impact on functional activities. However, the study of abdominal pain/discomfort within distinct bowel pattern subgroups is challenged by the various methodological approaches that can be taken. Often in clinical practice or research protocols, retrospective questionnaires are used. But this information may not capture the typical bowel pattern. For example, in one study investigators noted that women with functional constipation had difficulty remembering if symptoms had occurred more or less during a 6-month period [9]. Daily pain and stooling recorded over 4 weeks may provide different information than retrospective recall over several months.

Subtypes of IBS based on retrospective recall will be clinically much more practical and useful than subtypes based on a several week diary. Therefore, in this report we propose using retrospective recall of symptoms over the past 3 months to classify women with IBS into 6 subtypes based on further dividing each of the three bowel pattern subtypes into high pain and low pain groups. The concordance of these subtypes with 4-week diary data is first evaluated. Then we tested for differences across subtypes in QOL, impact on work and daily activities, daily symptoms, and cognitive beliefs about IBS. We hypothesize that clinically meaningful differences will be evident across the 6 subtypes, more so than across just the three bowel pattern subtypes. Specifically, we hypothesize that subjects in the high pain subtypes will have substantially worse QOL and other outcomes than those in the corresponding low pain subtypes.

Methods

Data for this analysis were derived from the baseline assessment period from a randomized controlled trial design of a cognitive behavioral self management program. A more detailed description of methods has been published previously [10]. Women with IBS completed interviews, questionnaires, and kept a diary for 28 days. Volunteers with IBS were recruited through community advertisements and a single mailing to patients in a university-based gastroenterology practice.

Women were eligible if over 18 years of age, had a prior diagnosis of IBS made by a health care provider, and reported current IBS symptoms (Rome-II criteria). Participants were excluded if they had a history of coexisting GI pathology (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease) or surgery (e.g., bowel resection), renal, or reproductive pathology (e.g., endometriosis). Subjects were excluded for conditions such as severe fibromyalgia, type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus, infectious diseases (e.g., hepatitis B or C, HIV), symptoms of dementia, severe cardiovascular disease, severe depression, or current substance abuse. Human subjects institutional review approval was obtained prior to enrolling participants and consent obtained from subjects.

Subjects were assessed for eligibility at the initial telephone screening. Next, subjects were met in person to obtain written consent and have questionnaires completed. Subjects were given a 4-week symptom diary to be completed each evening. All data were reviewed by a gastroenterologist to determine whether the diagnosis of IBS was appropriate and there were no red flags that indicated a need for further assessment.

METHODS

Rome II Diagnostic Questionnaire for Functional GI Disorders was used to assess abdominal pain and IBS symptoms severity over the previous 1 year [11]. The questionnaire is based the criteria for FGIDs in adults including: gastroduodenal, bowel (e.g., IBS), functional abdominal pain, esophageal, biliary, and anorectal disorders [11].

Symptoms and Stool Consistency: Daily Diary

Subjects completed a symptom diary that contained 26 symptoms, which were rated every evening. Each symptom was rated on a scale from 0 (not present) to 4 (extreme). GI pain/discomfort symptoms in the daily diary included abdominal pain, abdominal distension, bloating, and intestinal gas. GI symptoms related to stool characteristics were diarrhea, constipation, and urgency. Psychological/emotional items include anger, anxiety, depressed or blue, stressed, fatigue/tiredness, and sleepiness during the day. Somatic symptoms were backache, headache, joint pain and muscle pain. The daily diary also included a rating of consistency for each stool on a 5-point scale: very hard, hard, formed, loose, watery. A summary score was used in the analysis.

Quality of Life

The IBS-Quality of Life (IBSQOL) questionnaire is a 42-item questionnaire with nine scales: sleep, emotional, mental health beliefs, energy, physical functioning, diet, social role, physical role, and sexual relations [12]. Example questions are “How often did your IBS make you feel fed up or frustrated” e.g., 1 (always), 2 (often), 3 (sometimes), 4 (seldom) to 5 (never); or “My IBS affected my ability to succeed at work/main activity” e.g., 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). The scales are transformed to a standard 0 to 100 scale. A total score was computed by averaging all but one of the scales (sexual relations). Extensive and acceptable validity and reliability tests have been conducted 10]. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for the scales ranged from α = 0.73 to 0.93 for this study. A summary score was used.

Cognitive beliefs

The Cognitive Scale for Functional Bowel Disorders (CSFBD) describes 25 cognitive beliefs related to functional bowel disorders [13]. The items are rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A typical item is, “I often worry that there might not be a bathroom available when I need it.” The CSFBD has high concurrent criterion validity, acceptable convergent validity, and high content validity and face validity with minimal social desirability contamination. The internal consistency for this study was α = 0.937. The summary score was the mean of all items.

Work Productivity and Activity

The Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI) was adapted for persons with IBS [14]. It includes 9 questions related to the impact of IBS on work and other regular activities. Construct validity is acceptable when tested against known measures in employed individuals affected by a health problem. The test-retest (1-day) ranged from r = 0.71 to 0.95 for the items [14]. For this analysis two scales were used, the Overall Work Productivity Loss (missed work and work impairment due to IBS) and the Daily Activity Impairment scales (impairment while working due to IBS). In addition the WPAI additional items were added to the diary including ‘how much did your IBS symptoms affect your ability to carry out normal daily activities, other than work?’ and ‘did you go to work/school today?’

Other Variables

Demographic information included age, marital status, years of education, ethnic affiliation, occupation, body mass index, age when IBS pain began, and medication use. A retrospective measure of psychological distress, the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) was completed. It includes 53 items that measure psychological distress. Participants were asked to rate how much the symptom distressed or bothered them over the prior 7 days on a scale from not at all ‘0’ to extremely distressing ‘4’. For this study the Global Severity Index (GSI: mean of all 53 items) are reported. Acceptable indicators of validity and reliability have been described [15]. The internal consistency of the GSI was α = 0.96 in this study.

Analyses

The Rome III criteria [16] for defining bowel pattern subgroups are based only on stool consistency. Two questions on the Rome II Diagnostic Questionnaire for Functional GI Disorders ask how often, in the last three months, you have had ‘lumpy or hard bowel movements (stools)’ and ‘loose, mush or watery bowel movements (stools)’. IBS patients who answered at least ‘often’ to both questions were classified as mixed (IBS-M), those who answer ‘often’ or greater only to hard stools were classified as constipation-predominant (IBS-C) while those who answer at least ‘often’ only to loose stools were classified as diarrhea-predominant (IBS-D). Those who answered less than ‘often’ to both questions were excluded from the analyses.

Because pain/discomfort is a central component of the diagnosis of IBS, we chose to include this symptom in the subtyping. To increase the likelihood of differentiating groups as well as making them more clinically applicable we classified participants as either high pain or low pain based on two questions on the Rome II Diagnostic Questionnaire for Functional GI Disorders [11] that ask about the frequency and severity of ‘discomfort or pain in your belly or abdomen’ in the past 3 months. The high pain group consisted of those IBS patients who reported having either ‘moderate’ pain that occurred at least ‘very often’ or ‘severe’ pain/discomfort that occurred at least ‘often’.

Scatterplots were used to examine how well diary measures of diarrhea, constipation, stool consistency, and abdominal pain agreed with the pain and bowel pattern classifications based on the retrospective questionnaire.

Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to test the association of each outcome variable to pain level, predominant bowel pattern and the interaction between the two, while controlling for age. The interaction term tests whether the effect of pain level on the outcome was the same in all three bowel pattern subgroups.

RESULTS

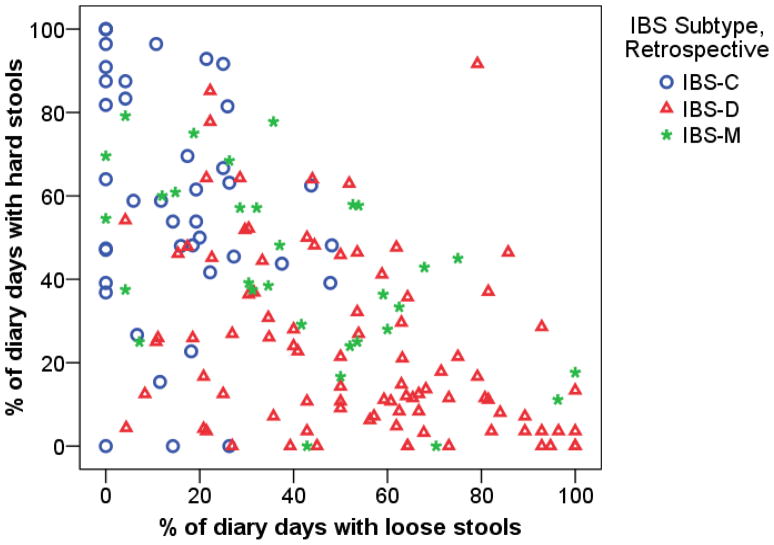

Figure 1 illustrates the association between stool consistency as measured retrospectively and prospectively on the daily diary. The three predominant bowel pattern groups are defined based on the retrospective Rome II questionnaire, while the two axes of the plot show percent of days with hard and loose stools as determined from the daily diary. The figure shows moderate congruence between the diary and questionnaire (recall) data with fairly good separation between the IBS-C (upper left) and IBS-D (lower right) groups, with the IBS-M group in between and overlapping with both of the other groups. Eighty-eight percent of IBS-C subjects have more days with hard stools than with loose stools, 73% of IBS-D subjects have more days with loose stools than with hard stools, and 50% of IBS-M patients have more days with loose stools than with hard stools.

Figure 1.

Comparison of IBS bowel pattern subtype groups defined by retrospective questionnaire to percent of days with hard and loose stools from daily diary.

Participants were further classified into 6 categories based on predominant bowel pattern and pain severity (constipation vs. diarrhea vs. mixed X high and low pain). Table 1 shows a comparison of the demographics across these 6 categories. Overall 55% of participants are in the high pain group. The fraction of participants in the IBS-C group with high pain is somewhat higher than in the IBS-M and IBS-D groups but this difference is not statistically significant (P=0.581).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome Based on Retrospective Report of Abdominal Pain and Bowel Pattern Predominance

| IBS-Constipation | IBS-Diarrhea | IBS-Mixed | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Pain (n=15) | High Pain (n=26) | Low Pain (n=42) | High Pain (n=47) | Low Pain (n=15) | High Pain (n=16) | |

| Age mean (SD) | 44.3 (13.8) | 46.2 (13.7) | 40.7 (15.0) | 45.1 (13.2) | 41.4 (13.8) | 42.1 (16.8) |

| Income>$50,000, n (%) | 6 (35.3) | 10 (38.5) | 26 (59.1) | 23 (44.2) | 8 (44.4) | 12 (66.7) |

| Income≥$50,000, n (%) | 11 (64.7) | 16 (61.5) | 18 (40.9) | 29 (55.8) | 10 (55.6) | 6 (33.3) |

| Married/partnered, n (%) | 8 (47.1) | 15 (55.6) | 16 (35.6) | 24 (44.4) | 7 (38.9) | 5 (27.8) |

| College Education, n (%) | 12 (70.6) | 16 (59.3) | 27 (60.0) | 29 (53.7) | 10 (55.6) | 6 (33.3) |

| White, n (%) | 16 (94.1) | 25 (92.6) | 42 (93.3) | 50 (92.6) | 16 (88.9) | 16 (88.9) |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Non-professional, n (%) | 8 (47.1) | 11 (40.7) | 21 (46.7) | 25 (46.3) | 10 (55.6) | 10 (55.6) |

| Professional, n (%) | 9 (52.9) | 16 (59.3) | 24 (53.3) | 29 (53.7) | 8 (44.4) | 8 (44.4) |

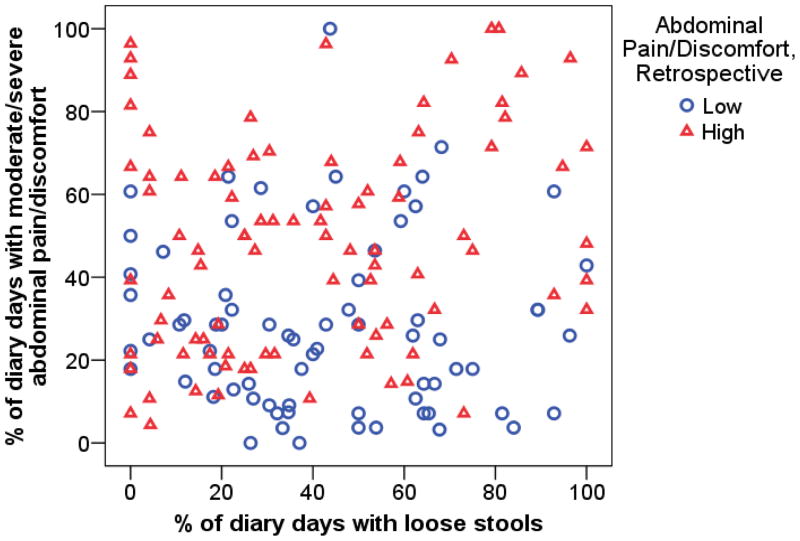

Figure 2 shows that the average percent of diary days with moderate/severe abdominal pain is considerably higher in the questionnaire-based high pain group. However, there is quite a bit of overlap between the two distributions. This figure also shows that there is very little association between percent of days with moderate/severe abdominal pain/discomfort and percent of days with loose stools.

Figure 2.

Comparison of abdominal pain category defined by retrospective questionnaire to percent of days with moderate/severe abdominal pain and percent of days with loose stools from daily diary.

The results in Table 2 confirm the observations in Figures 1 and 2. Percent of days with hard and loose stools differ significantly by bowel pattern group but not by pain group or the interaction between the two. Similar results hold for percent of days with moderate/severe constipation and diarrhea. Percent of days with moderate/severe abdominal pain differs by pain group but not by bowel pattern group. Most of the other IBS symptoms show a pattern similar to abdominal pain, except for urgency.

Table 2.

Daily Stool Characteristics and Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Women with IBS-Constipation, IBS-Diarrhea, and IBS-Mixed

| IBS-Constipation | IBS-Diarrhea | IBS-Mixed | p-values1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Pain (n=15) | High Pain (n=26) | Low Pain (n=42) | High Pain (n=47) | Low Pain (n=15) | High Pain (n=16) | Bowel pattern | Pain | Inter-action | |

| Stool Characteristics (mean ± SD) | |||||||||

| % of days with hard stools | 54.1 (26.6) | 61.2 (29.4) | 24.5 (21.6) | 22.6 (21.9) | 40.1 (21.6) | 44.3 (22.4) | <.001 | .656 | .617 |

| % of days with loose stools | 15.5 (16.8) | 13.7 (12.3) | 52.6 (24.3) | 54.0 (27.4) | 42.1 (23.6) | 38.9 (29.7) | <.001 | .954 | .862 |

| Mean stools/day (n) | 1.78 (1.43) | 1.71 (.983) | 2.24 (.845) | 2.24 (1.03) | 1.98 (.879) | 2.17 (1.10) | .022 | .961 | .790 |

| Moderate/Severe Symptom Days (% ± SD) | |||||||||

| Abdominal pain/discomfort | 34.1 (22.6) | 41.1 (27.4) | 29.2 (20.9) | 49.7 (26.7) | 20.5 (18.0) | 55.1 (18.5) | .719 | <.001 | .091 |

| Abdominal pain after eating | 29.8 (25.2) | 34.9 (28.7) | 22.6 (23.7) | 37.5 (27.5) | 20.5 (19.2) | 43.3 (22.0) | .970 | .001 | .447 |

| Abdominal distension | 27.9 (33.5) | 41.7 (33.8) | 21.1 (22.6) | 39.7 (34.9) | 19.6 (25.2) | 50.3 (29.6) | .807 | <.001 | .418 |

| Bloating | 37.8 (35.1) | 49.0 (33.9) | 25.1 (25.3) | 45.8 (32.9) | 22.3 (26.7) | 44.6 (26.1) | .434 | <.001 | .673 |

| Intestinal gas | 46.7 (29.6) | 47.3 (30.7) | 31.5 (26.6) | 50.1 (31.6) | 26.3 (24.7) | 50.9 (26.8) | .760 | .002 | .129 |

| Flatulence | 46.1 (31.0) | 45.6 (31.5) | 38.3 (25.3) | 52.6 (30.0) | 38.5 (27.5) | 55.0 (26.9) | .874 | .025 | .337 |

| Constipation | 39.4 (28.9) | 44.6 (31.0) | 11.3 (15.6) | 17.1 (21.3) | 20.9 (16.0) | 32.5 (21.5) | <.001 | .030 | .807 |

| Diarrhea | 5.81 (7.80) | 4.36 (7.73) | 17.2 (13.0) | 24.2 (25.2) | 11.9 (13.6) | 17.8 (25.0) | <.001 | .083 | .459 |

| Urgency | 6.23 (7.08) | 9.43 (14.4) | 22.6 (19.9) | 25.9 (24.1) | 15.3 (15.1) | 23.6 (26.9) | <.001 | .168 | .920 |

p values are for the main effects of predominant bowel pattern (constipation, diarrhea, mixed) and pain severity (high versus low) and the interaction between them using ANCOVA model controlling for age.

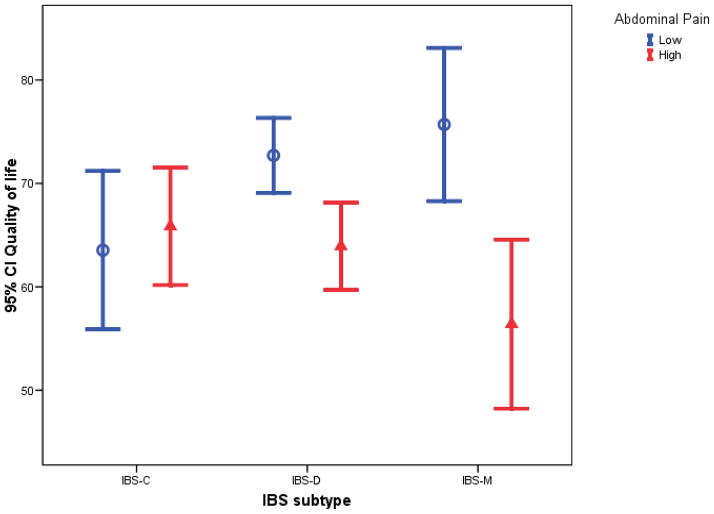

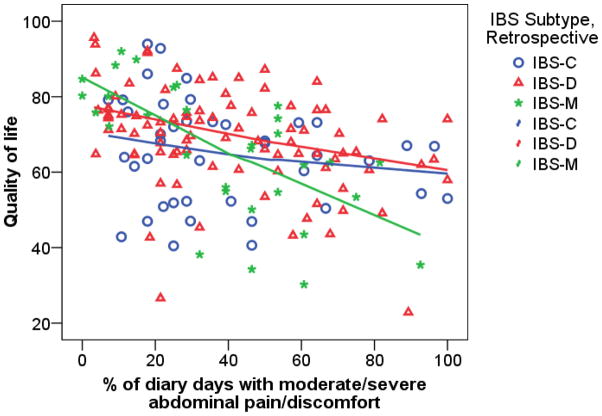

Table 3 gives results for measures of QOL, cognitive beliefs about IBS (CSFBD), psychological distress, and the impact of IBS on work and other activities. Note the very significant effect on QOL of pain severity and the interaction between pain and bowel pattern. There is a very strong effect of abdominal pain severity on QOL among IBS-M patients and somewhat lesser among IBS-D, versus no effect of pain severity among IBS-C patients. The pattern of means is illustrated in Figure 3. Figure 4 shows that a similar effect holds when abdominal pain severity is measured with the diary. Among IBS-M subjects there is a very strong effect of pain severity on QOL as seen by the steep slope for the IBS-M group and the fact that most of the IBS-M subjects with fewer than 40% of days with moderate/severe pain have very good QOL (>70), while most of those with more than 40% of days with moderate/severe pain have very poor QOL. Exploration of the subscales of QOL (results not shown) shows that the work impact subscale shows the strongest interaction effect. A similar interaction effect and main effect of pain severity is seen in the analyses of the diary items concerning impact of IBS on work productivity and other activities, but not the retrospective report of work interference.

Table 3.

Quality of Life, Cognitive Functions Related to IBS, Psychological Distress, Impact on Activity, and Daily Symptoms in Women with IBS-Constipation, IBS-Diarrhea, and IBS-Mixed

| Measures | IBS-Constipation | IBS-Diarrhea | IBS-Mixed | p-values1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Pain (n=17) | High Pain (n=27) | Low Pain (n=43) | High Pain (n=51) | Low Pain (n=18) | High Pain (n=18) | Bowel pattern | Pain | Inter- action | |

| Quality of Life | 63.5 (13.8) | 65.9 (14.0) | 72.7 (11.9) | 63.9 (14.5) | 75.7 (13.4) | 56.4 (15.3) | .536 | <.001 | .007 |

| Cognitive Beliefs about IBS | 4.9 (.638) | 4.47 (.972) | 4.22 (1.03) | 4.69 (1.08) | 4.11 (1.22) | 5.07 (.978) | .660 | .023 | .016 |

| Global Severity Index | .463 (.282) | .574 (.486) | .382 (.326) | .513 (.391) | .485 (.574) | .661 (.399) | .253 | .024 | .942 |

| Work Productivity and Activity | |||||||||

| Work Productivity Loss | 32.1 (24.3) | 34.5 (30.1) | 21.6 (21.2) | 32.0 (21.6) | 24.1 (20.0) | 31.4 (20.4) | .499 | .051 | .698 |

| Daily Activity Impairment | 32.4 (20.8) | 39.3 (31.2) | 28.1 (18.2) | 38.8 (24.8) | 30.0 (19.7) | 40.6 (21.8) | .829 | .004 | .889 |

| Diary Variables | |||||||||

| Days with some impact on work productivity (% ± SD) | 58.0 (31.3) | 45.9 (37.4) | 40.2 (29.0) | 49.6 (36.3) | 30.8 (21.8) | 74.5 (27.8) | .624 | .048 | .005 |

| Days with some impact on activities (% ± SD) | 56.7 (30.7) | 48.6 (36.4) | 40.4 (27.7) | 53.5 (32.6) | 30.9 (19.2) | 66.6 (26.6) | .874 | .012 | .012 |

| Psychological Distress Symptoms (% days ± SD)2 | |||||||||

| Anxiety | 24.8 (27.8) | 24.1 (23.7) | 15.5 (17.8) | 17.3(21.5) | 15.5(13.6) | 25.7 (19.3) | .126 | .367 | .571 |

| Depression | 12.1 (24.9) | 9.7 (14.9) | 8.7 (15.1) | 9.01 (12.3) | 10.5 (11.7) | 15.7 (13.2) | .394 | .774 | .610 |

| Fatigue | 31.2 (30.3) | 40.0 (32.0) | 28.3 (24.4) | 43.4 (28.5) | 31.6 (19.2) | 56.0 (26.0) | .244 | .001 | .411 |

| Sleepy | 15.8 (23.1) | 32.7 (28.6) | 20.6 (22.7) | 29.1 (25.2) | 17.1 (13.4) | 48.7 (26.1) | .207 | <.001 | .064 |

| Stressed | 22.7 (25.2) | 31.5 (27.5) | 21.6 (20.5) | 24.7 (22.6) | 21.3 (17.4) | 37.0 (26.3) | .335 | .055 | .472 |

| Somatic Symptoms (% days ± SD)2 | |||||||||

| Backache | 9.30 (23.9) | 18.6 (24.8) | 12.8 (18.8) | 26.4 (33.4) | 6.61 (9.54) | 28.6 (18.7) | .345 | .001 | .496 |

| Headache | 8.65 (10.9) | 15.6 (15.8) | 10.8 (13.4) | 21.4 (24.9) | 8.74 (7.28) | 25.8 (25.1) | .359 | <.001 | .536 |

| Muscle pain | 12.9 (28.5) | 32.1 (34.6) | 17.3 (24.2) | 21.5 (27.6) | 10.8 (13.0) | 21.7 (25.8) | .653 | .045 | .246 |

| Upper GI Symptoms (% days ± SD)2 | |||||||||

| Heartburn | 16.9 (26.8) | 5.14 (8.92) | 5.37 (11.1) | 11.9 (22.0) | 2.62 (5.31) | 9.82 (18.1) | .793 | .462 | .014 |

| Nausea | 14.1 (26.8) | 6.06 (10.9) | 5.03 (7.78) | 13.2 (20.8) | 3.39 (4.77) | 14.1 (14.1) | .983 | .053 | .017 |

p values are for the main effects of predominant bowel pattern (constipation, diarrhea, mixed) and pain severity (high versus low) and the interaction between them using ANCOVA model controlling for age.

Days with moderate to severe symptoms in diary

Figure 3.

95% confidence intervals for Quality of Life by IBS subtype and abdominal pain category.

Figure 4.

Comparison across IBS bowel pattern subtypes of the slope of the relationship of retrospective QOL to percent of days with moderate/severe abdominal pain from daily diary.

Table 3 also shows results for diary items related to psychological distress, somatic symptoms, and upper GI symptoms. There is no evidence of an effect of predominant bowel pattern on any of these symptoms. Abdominal pain severity does appear to have an effect on some psychological distress and somatic symptoms (fatigue and sleepy, backache and headache), but no evidence of interaction effects. There is some evidence of an interaction effect for heartburn and nausea. It is interesting to note that depression and anxiety measured by daily diary do not differ across pain or bowel pattern groups.

DISCUSSION

In practice clinicians diagnose and make treatment decisions based on predominant bowel pattern characteristics. However, findings from the current study indicate that regardless of bowel pattern, those patients with more frequent or severe abdominal pain/discomfort report greater psychological distress, more negative cognitions about IBS, reduced QOL, and more interruptions in daily activities.

This study evaluated the agreement of daily diary ratings of pain severity and stool consistency with IBS subtypes defined using retrospective ratings of pain severity and frequency and stool consistency. There is moderately good agreement between the diary and retrospective IBS group subtypes. Since different time periods are being rated (subjects began keeping the diary after giving their retrospective rating of the past year), perfect agreement would not be expected. Digesu and colleagues [9] utilizing respondents from urogynecology, gynecology, and colorectal clinics found that women had difficulty recalling bowel symptoms that had occurred even within a 6-month period. With recall there is the potential for recall bias to influence responses to bowel questionnaires [17–19]. IBS symptoms wax and wane over time along with predominant bowel pattern making it challenging to determine treatment outcomes using bowel patterns only [20, 21].

The daily diary used in the current study incorporated consistency rating of every stool as well as symptom severity ratings of a variety of symptoms. Degen and Phillips utilizing healthy young to middle-aged adults observed that the extremes of stool form (i.e., hard and loose texture) as recorded in stool diary were useful in discriminating between slow and fast colonic transit [22]. Findings from the current study reveal congruence between daily stool frequency and consistency and designation of Rome II subgroups based on recall. However, as illustrated in the Figures there is considerable variability in daily stool reports within each of the three predominant bowel pattern subgroups. These results support the inclusion of abdominal pain/discomfort severity as part of the diagnostic criteria for IBS.

The second aim of this study was to describe differences in QOL and other measures across the 6 subtypes. We found that in general, abdominal pain severity seems to have a bigger impact on QOL, IBS interference with work and activities and cognitive beliefs about IBS than does bowel pattern subtype. However, the strong influence of abdominal pain severity seems to be limited to the IBS-M and IBS-D groups. The results suggests that it is the presence of abdominal pain rather than the stool pattern that contributes to overall distress and reductions in QOL in women with diarrhea or mixed diarrhea and constipation.

These results are consistent with our earlier results, based on a different sample of women aged 18–48, that abdominal pain was most strongly related to life impact variables and QOL [4]. Analysis of day-to-day variation within women showed that abdominal pain was most strongly correlated with daily life impact variables and that constipation had the weakest correlation.

Chronic abdominal pain/discomfort is an essential component of the diagnosis of IBS. Under laboratory testing conditions, the measurement of pain thresholds in many patients with IBS (i.e., IBS-C, IBS-D, IBS-M) demonstrate heightened responsiveness to painful stimuli (discomfort reported at lower balloon volume). Several investigators have addressed the relationship between laboratory measurement of visceral sensitivity and report of urge, discomfort and pain [23]. For the most part, these studies indicate that visceral sensitivity is comparable across bowel pattern subgroups. Using Rome II criteria to distinguish bowel pattern subgroups the proportion of patients within different predominant bowel habit groups have equal numbers with and without heightened rectal perception [24, 25]. In addition, Kanazawa found that pain thresholds and motility index were not correlated in 3 IBS bowel pattern subgroups (IBS-C, IBS-D, IBS-M) [23]. Consistent with this, Dorn and colleagues using the ascending methods of limits in a sample of IBS-C, IBS-D and IBS-unclassified patients showed that increased colonic sensitivity was influenced by a psychological tendency to report pain and urge rather than neurosensory sensitivity [26].

In the current study there was significant effect of pain group on recalled greater psychological distress and negative cognitions. Several investigators have employed retrospective measures of both GI and psychological distress to examine the associations of pain or discomfort severity with perceptual sensitivity [24, 27, 28]. Posserud utilized the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale-IBS for pain, bloating, constipation, diarrhea, satiety and found that compared to patients with normal rectal perception, patients with altered perception more frequently reported at least moderate pain, bloating and diarrhea [24]. Using a multivariate approach to determine independent factors associated with GI symptom severity they found pain and pain along with gender (female) and anxiety contributed to 48% of the variance in perceived sensitivity to visceral stimuli. Adding to this is more recent data showing that psychological factors may account for IBS-D versus control group differences in peripheral pain inhibition as well as visceral hypersensitivity [29].

Others have suggested that subgroups of patients with functional GI disorders based on bowel patterns alone may not sufficiently identify clinically distinct entities [30, 31]. Our results suggest that abdominal pain severity may constitute the basis for meaningful subtypes. They also suggest that mechanistically pain and bowel pattern are separate but overlapping phenomenon.

Within the IBS-D and IBS-M groups there was a clear separation in daily pain-related diary symptoms between the high pain and low pain subgroups, while such a separation is not apparent in the IBS-C group. The reason for the lack of separation in the constipation group is not clear, though it may be related to the fact that women with IBS-C low pain tended to report more daily symptoms and worse QOL than women in the low pain IBS-D and IBS-M groups. The degree of constipation bowel pattern ‘severity’ in the IBS-C high and low pain groups were similar as evidenced by percentage of days with hard stools and report of constipation.

The current study was of women with IBS and whether similar results would be found in men with IBS remains to be determined. In a study comparing men and women with and without IBS, Chang and colleagues [32] noted a significant lowering of discomfort thresholds after noxious sigmoid stimulation in women but not men with IBS. Women also reported more unpleasant abdominal pain over the previous 6 months. Gender differences in IBS as well as other chronic conditions associated with visceral pain have been well described [2, 33].

Our sample was based on community recruitment and most likely includes some patients with less severe symptoms than would a sample recruited from a gastroenterology referral center. Thus, this sample is likely more representative of those patients seen in primary care settings. However, those with high pain/discomfort levels may be similar to those attending a gastroenterology clinic.

Conclusion

Taking abdominal pain/discomfort severity into account when categorizing patients with IBS leads to subtypes which differ on quality of life and other related outcomes, much more so than subgroups based solely on predominant bowel pattern. Further investigation is needed into whether such subtyping is useful to clinicians deciding on treatment recommendations or researchers designing clinical trials or other studies.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by the following grants: 1RC2NR011959, NR04142, P30 NR04001.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services NIH. Opportunities and Challenges in Digestive Diseases Research: Recommendations of the National Commission on Digestive Diseases. National Institute of Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adeyemo MA, Spiegel BM, Chang L. Meta-analysis: do irritable bowel syndrome symptoms vary between men and women? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;16(3):299–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitehead WE, Drossman DA. Validation of symptom-based diagnostic criteria for irritable bowel syndrome: a critical review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:814–820. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cain KC, Headstrom P, Jarrett ME, et al. Abdominal pain impacts quality of life in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:124–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bond B, Quinlan J, Dukes GE, Mearin F, Clouse RE, Alpers DH. Irritable bowel syndrome: more than abdominal pain and bowel habit abnormalities. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:73–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spiegel BM, Bolus R, Agarwal N, et al. Measuring symptoms in the irritable bowel syndrome: development of a framework for clinical trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:1275–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorn SD, Morris CB, Hu Y, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome subtype defined by Rome II and Rome III criteria are similar. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:214–220. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31815bd749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cain KC, Jarrett ME, Burr RL, Rosen S, Hertig VL, Heitkemper MM. Gender differences in gastrointestinal, psychological, and somatic symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1542–9. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0516-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Digesu GA, Panayi D, Kundi N, Tekkis P, Fernando R, Khullar V. Validity of the Rome III Criteria in assessing constipation in women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2010 May 25; doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1179-0. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarrett ME, Cain KC, Burr RL, Hertig VL, Rosen SN, Heitkemper MM. Comprehensive self-management for irritable bowel syndrome: randomized trial of in-person vs. combined in-person and telephone sessions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(12):3004–14. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drossman D, Corazziari E, Talley N, Thompson W, Whitehead WE. Rome II: The functional gastrointestinal disorders. McLean: Degnon Associates, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hahn BA, Kirchdoerfer LJ, Fullerton S, Mayer E. Evaluation of a new quality of life questionnaire for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:547–552. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.00168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toner BB, Stuckless N, Ali A, Downie F, Emmott S, Akman D. The development of a cognitive scale for functional bowel disorders. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:492–497. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199807000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work Ringel Y, Williams RE, Kalilani L, et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and impact of bloating symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastrotenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Derogatis L. BSI: Brief Symptom Inventory; Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual. 4. Minneapolis: National Computer Systems; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, Spiller RC, Talley NJ, Thompson WG, Whitehead WE. Rome III: The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. McLean, VA: Degnon Associates, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCrea GL, Miaskowski C, Stotts NA, Macera L, Paul SM, Varma MG. Gender differences in self-reported constipation characteristics, symptoms, and bowel and dietary habits among patients attending a specialty clinic for constipation. Gend Med. 2009;6:259–71. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varma MG, Wang JY, Berian JR, Patterson TR, McCrea GL, Hart SL. The constipation severity instrument: a validated measure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(2):162–172. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bharucha AE, Seide BM, Zinsmeister AR, Melton JL., III Relation of bowel habits to fecal incontinence in women. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1470–1475. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01792.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pamuk ON, Pamuk GE, Celik AF. Revalidation of description of constipation in terms of recall bias and visual scale analog questionnaire. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:1417–1422. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.03155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halder SL, Locke GR, III, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ, III, Talley NJ. Natural history of functional gastrointestinal disorders: a 12-year longitudinal population-based study. Gastroenterol. 2007;133:799–807. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Degen LP, Phillips SF. How well does stool form reflect colonic transit? Gut. 1996;39:109–113. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanazawa M, Palsson OS, Thiwan SI, et al. Contributions of pain sensitivity and colonic motility to IBS symptom severity and predominant bowel habits. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2550–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Posserud I, Syrous A, Lindström L, Tack J, Abrahamsson H, Simrén M. Altered rectal perception in irritable bowel syndrome is associated with symptom severity. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1113–23. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuiken SD, Lindeboom R, Tytgat GN, Boeckxstaens GE. Relationship between symptoms and hypersensitivity to rectal distension in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:157–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dorn SD, Palsson OS, Thiwan SI, et al. Increased colonic pain sensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome is the result of an increased tendency to report pain rather than increased neurosensory sensitivity. Gut. 2007;56:1202–1209. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.117390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zar S, Benson MJ, Kumar D. Rectal afferent hypersensitivity and compliance in irritable bowel syndrome: differences between diarrhoea-predominant and constipation-predominant subgroups. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:151–158. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200602000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poitras P, Riberdy Poitras M, Plourde V, Boivin M, Verrier P. Evolution of visceral sensitivity in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;474:914–910. doi: 10.1023/a:1014729125428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piche M, Arsenault M, Poitras P, Rainville P, Bouin M. Widespread hypersensitivity is related to altered pain inhibition processes in irritable bowel syndrome. Pain. 2010;148(1):49–58.28. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Talley NH, Boyce P, Jones M. Identification of distinct upper and lower gastrointestinal symptom grouping in an urban population. Gut. 1998;42:690–695. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.5.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong RK, Palsson OS, Turner MJ, et al. Inability of the Rome III Criteria to distinguish functional constipation from constipation-subtype irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 May 27; doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.200. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang L, Mayer EA, Labus JS, et al. Effect of sex on perception of rectosigmoid stimuli in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Physiol. 2006;291(2):R277–84. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00729.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee KJ, Kim JH, Cho SW. Relationship of underlying abnormalities in rectal sensitivity and compliance to distension with symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion. 2006;73:133–41. doi: 10.1159/000094099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]