Abstract

Immunosuppressive lentivirus infections, including human, simian, and feline immunodeficiency viruses (HIV, SIV, and FIV, respectively), cause the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), frequently associated with AIDS enteropathy. Herein, we investigated the extent to which lentivirus infections affected mucosal integrity and intestinal permeability in conjunction with immune responses and activation of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress pathways. Duodenal biopsies from individuals with HIV/AIDS exhibited induction of IL-1β, CD3ε, HLA-DRA, spliced XBP-1(Xbp-1s), and CHOP expression compared to uninfected persons (P<0.05). Gut epithelial cells exposed to HIV-1 Vpr demonstrated elevated TNF-α, IL-1β, spliced Xbp-1s, and CHOP expression (P<0.05) together with calcium activation and disruption of epithelial cell monolayer permeability. In addition to reduced blood CD4+ T lymphocyte levels, viral loads in the gut and plasma were high in FIV-infected animals (P<0.05). FIV-infected animals also exhibited a failure to gain weight and increased lactulose/mannitol ratios compared with uninfected animals (P<0.05). Proinflammatory and ER stress gene expression were activated in the ileum of FIV-infected animals (P<0.05), accompanied by intestinal epithelial damage with loss of epithelial cells and leukocyte infiltration of the lamina propria. Lentivirus infections cause gut inflammation and ensuing damage to intestinal epithelial cells, likely through induction of ER stress pathways, resulting in disruption of gut functional integrity.—Maingat, F., Halloran, B., Acharjee, S., van Marle, G., Church, D., Gill, M. J., Uwiera, R. R. E., Cohen, E. A., Meddings, J., Madsen, K., Power, C. Inflammation and epithelial cell injury in AIDS enteropathy: involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress.

Keywords: ER stress, HIV, FIV, gut, lentivirus, disease

In humans infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1, a rapid and marked depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes occurs in the gut-associated lymphoid tissues, proximal to the mucosa (1, 2). The loss of this population of T cells may contribute to mucosal immunodeficiency and ensuing gut opportunistic infections. However, there is also intrinsic damage to the gut in the absence of secondary infections (termed AIDS enteropathy; ref. 3), which can occur acutely after primary infection and continue into the advanced stage of disease (4). This enteropathy is presumably caused by the virus through direct damage mediated by virus-encoded proteins or pathogenic actions of host-derived molecules such as cytokines, chemokines, and reactive oxygen species produced by resident gut cells or infiltrating leukocytes (5, 6). During the later stages of HIV infection, the enteropathy manifests as villous atrophy and blunting, enterocyte loss, inflammation within the submucosa with reduced regeneration, and dedifferentiation of epithelial cells within the gut (7). These events are accompanied by weight loss, malabsorption, malnutrition, diarrhea, and chronic pain, likely due to down-regulation of genes implicated in lipid metabolism, cell cycle regulation, and digestion (8). Moreover, these latter signs and symptoms also occur in children infected with HIV, resulting in developmental delays and failure to thrive.

Despite the recognition of these clinical and pathological features and their apparent, albeit partial, amelioration with combination antiretroviral therapy, the underlying disease mechanisms for AIDS enteropathy remain unclear. Inflammation within the gut in diseases such as Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis has recently been linked to the unfolded protein response and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress (9). ER stress and its ensuing inflammation is characterized by the up-regulation of the prototypic ER stress markers X-box binding protein-1 spliced variant (XBP-1s) and C/EBP (CCAAT enhancer binding protein) homologous protein (CHOP). Intestinal epithelial cells appear to be most vulnerable to ER stress within the gut, resulting in increased permeability and malabsorption.

Like HIV, feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) is an immunosuppressive lentivirus, which infects lymphocytes and macrophages with high levels of viremia, consequently depleting CD4+ T lymphocytes (10). Furthermore, FIV infection results in marked immunosuppression with accompanying multisystem disorders, evident as encephalopathy, weight loss, diarrhea, and secondary infections, which respond positively to antiretroviral therapy (11). FIV is structurally similar to HIV, containing gag, pol, env sequences, and, in particular, encodes an accessory protein, open reading frame A (ORF-A), an ortholog of the HIV-1 viral protein R (Vpr), which is involved in regulation of G2 cell cycle proteins and apoptosis, resulting in immune dysfunction (12). More recently, Vpr has been shown to directly induce ERK- and caspase 8-dependent apoptosis in epithelial cells (13). Indeed, HIV-1 and FIV also share a common nonstructural ortholog, which encodes an open reading frame: Vpr for HIV-1 and ORF-A for FIV, both of which exert similar effects on the virus and host. For these reasons, FIV infection represents a desirable model for studying HIV/AIDS pathogenesis, from which pathogenic mechanisms might be elucidated and antiretroviral therapies can be tested in vivo.

In the present studies, it was hypothesized that lentivirus infections mediate injury of the gut through mechanisms involving host inflammatory responses and direct viral protein actions, which contribute to reduced gut cell viability. By adopting a multiplatform approach using clinical samples, ex vivo assays, and a unique animal model, lentivirus infections were shown to cause intestinal epithelial cell damage contributing to loss of mucosal integrity, together with inflammation within the lamina propria associated with ER stress. These findings highlight novel feline lentivirus models of AIDS enteropathy and implicate several host and viral factors, which contribute to the development of enteropathy and might serve as future therapeutic targets.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses

Culture supernatants from feline peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) infected with an infectious molecular clone (FIV-Ch) served as sources of infectious FIV (14) for the in vivo experiments. Viruses were titered by limiting dilution, as previously reported (15).

Human duodenal samples

Human gut tissue (duodenal) was collected at biopsy and stored at −80°C from HIV-infected (HIV+, n=4) and noninfected (HIV−, n=4) control patients with their consent and with approval by the University of Calgary Ethics Committee. All HIV-infected individuals were AIDS defined and displayed evidence of AIDS enteropathy. Controls comprised age-matched, uninfected subjects, none of whom exhibited symptoms of enteropathy (16). HIV+ subjects received either didanosine or zidovudine treatment, while HIV− (control) patients did not receive any treatment.

Animals and virus infection

Adult specific pathogen-free pregnant cats (queens) were housed according to University of Alberta and University of Calgary animal care facility guidelines, in agreement with Canadian Council on Animal Care (CCAC) guidelines. All queens were negative for feline retroviruses (FIV, FeLV) by PCR analysis and serological testing. At d 1 postnatal, animals were infected with 200 μl of FIV-Ch29 at 104 TCID50/ml in accordance with CCAC guidelines, as described previously (15, 17). Control animals (FIV−) received heat-inactivated virus. Animals were weaned at 6 wk and monitored for 12–15 wk postinfection, during which time changes in body weight and neurobehavioral tests were conducted, and samples were taken for analyses of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations. At 12 or 15 wk, the animals were euthanized by pentobarbital overdose; ileum and plasma were harvested at this time. Samples were frozen immediately at −80°C for subsequent protein or total RNA extractions. Gut tissue was fixed in 4% buffered (pH 7.4) paraformaldehyde for immunocytochemical analysis.

Flow cytometry analysis

PBMCs were isolated from blood of FIV− and FIV+ animals at wk 8, 12, and 15 as previously reported (18). PBMCs were labeled with antifeline CD4 or CD8 monoclonal antibodies, and FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1 antibody was used a secondary. Omitting the primary antibody served as a control. FACS analysis was performed using the FACSCanto flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Plasma and gut viral load

Using a quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR protocol in which the oligonucleotide primers were derived from the FIV pol gene, the number of copies of viral RNA in plasma and ileum (per microgram RNA) was determined (19).

Host gene analysis by real-time RT-PCR

First-strand cDNA was synthesized by using aliquots of 1 μg of total RNA prepared from ileum (experimental animals), duodenum (humans), and cultured human epithelial cells (T84 human colonic adenocarcinoma cell line) together with Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA, USA) and random primers (20). Specific genes were quantified by real-time PCR using the i-Cycler IQ system (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, ON, Canada). cDNA prepared from total RNA derived from plasma and gut tissues and cell cultures was diluted 1:1 with sterile water, and 5 μl was used as template per PCR reaction. The specific primers used in the real-time PCR are summarized (Table 1). Semiquantitative analysis was performed by monitoring, in real time, the increase of fluorescence of the SYBR Green dye on the Bio-Rad detection system, as previously reported (21) and expressed as relative fold change (RFC) compared to mock-infected samples.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used in real-time RT-PCR analyses

| Primer | Sequence, 5′-3′ | Tm (°C) | Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH forward | AGCCTTCTCCATGGTGGTGAA | 56–60 | Human/feline |

| GAPDH reverse | CGGAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCG | 56–60 | Human/feline |

| IL-1β forward | CCAAAGAAGAAGATGGAAAAGCG | 56 | Human/feline |

| IL-1β reverse | GGTGCTGATGTACCAGTTGGG | 56 | Human/feline |

| CD3ε forward | GATGCAGTCGGGCACTCACT | 58 | Human |

| CD3ε reverse | CATTACCATCTTGCCCCCAA | 58 | Human |

| HLA-DRA forward | GGACAAAGCCAACCTGGAAA | 58 | Human |

| HLA-DRA reverse | AGGACGTTGGGCTCTCTCAG | 58 | Human |

| Xbp-1 spliced forward | GCTGAGTCCGCAGCAGGT | 58 | Human |

| Xbp-1 spliced reverse | GCAGTGGCTGGATGAAAGCAGAT | 58 | Human |

| CHOP forward | GAGCTGGAACCTGAGGAGAGA | 58 | Human |

| CHOP reverse | GCCAGAGAAGCAGGGTCAA | 58 | Human |

| TNFα forward | CCCAGGGACCTCTCTCTAATCA | 56 | Human |

| TNFα reverse | GCTACAGGCTTGTCACTCGG | 56 | Human |

| CD8β forward | CCGACGATCATGCAGAAGTA | 56 | Human |

| CD8β reverse | GGTGAAGAGGTGGAACAGGA | 56 | Human |

| Xbp-1 spliced forward | TGAGCTGGAGCAGCAAGTGG | 58 | Feline |

| Xbp-1 spliced reverse | GCCTGCACCTGCTGCGGACT | 58 | Feline |

| CHOP forward | GGCTCAAGAGGAAGAACACG | 58 | Feline |

| CHOP reverse | ACCATTCGGTCAATCAGAGC | 58 | Feline |

| CD3ε forward | AAGCAAGAGTGTGTCAGAACT | 56 | Feline |

| CD3ε reverse | CTGATTCAGGCCAGAATACAG | 56 | Feline |

| F4/80 forward | CACGACGGAGTTACCCTTGT | 56 | Feline |

| F4/80 reverse | GCGAGGAAAAGGTAGTGCAG | 56 | Feline |

| TNFα forward | CCCCAGGGCTCCAGAAGG | 56 | Feline |

| TNFα reverse | TGGGGCAGAGGGTTGATTAGTTG | 56 | Feline |

Cell culture

T84 human colonic adenocarcinoma cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA); cells were seeded and grown in a 1:1 mixture of Ham's F12 medium and Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 2.5 mM l-glutamine, 95%; fetal bovine serum (FBS, Life Technologies, Burlington, ON, Canada), 5%; and maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2.

Soluble Vpr preparation

The procedure for producing full-length HIV-1 Vpr protein derived from pNL4-3 has been described previously (22, 23).

Vpr exposure to T84 cells

T84 cells were seeded in 24-well plates and grown in decreasing amounts of FBS with complete removal of FBS from the growth medium, 2 h prior to Vpr exposure. T84 cells were exposed to 100 and 200 nM Vpr or PBS in growth medium without FBS for 2 h, after which the medium was aspirated, and cells were washed and resuspended in TRIzol for total RNA extraction. Subsequent real-time RT-PCR was performed to determine T84 gene expression in response to Vpr exposure.

ECIS measurements in T84 cells exposed to Vpr

T84 monolayers were mounted into sterile 8-well gold microelectrode chambers for measurement of transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) using a real-time electric cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) system (Applied BioPhysics, Troy, NY, USA). Soluble Vpr (or PBS) was added to the wells at time 0. The array was mounted on the ECIS system within an incubator (37°C, 5% CO2). Changes in resistance in each well were measured for up to 8 h. The acquired data were analyzed for changes in resistance and capacitance using the ECIS software.

Calcium imaging

T84 cultures were plated in 35-mm Nunclon tissue culture dishes (VWR, Radnor, PA, USA). The 3-d-old cultures treated with 10 μM Fluo-8 acetoxymethyl ester (Fluo-8 AM; ABD Bioquest, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) for 1 h 30 min were imaged. Changes in Fluo-8 AM-fluorescence intensity evoked by a Vpr (50 nM) using an epifluorescence microscope equipped with an argon laser and filters (IX81 microscope system; Olympus, Markham, ON, Canada). During recording, the cells were perfused with a solution containing 137 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 147.1 mM CaCl2, 0.8 mM MgSO4, 0.3 mM Na2HPO4 · 7H2O, 0.4 mM KH2PO4, 4.2 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM HEPES, and 5 mM glucose. Full-frame images (512×512 pixels) were acquired at a scanning time of 3 s/frame using the Metamorph software (Olympus). Selected regions of interest were drawn around distinct cell bodies and traces of time course of change of fluorescence intensity were generated with Metamorph software (Olympus).

Intestinal permeability

Twelve-week-old animals were deprived of food overnight prior to gavaging with 10 ml of a solution consisting of 250 mg/ml sucrose, 60 mg/ml lactulose, and 40 mg/ml mannitol in sterile water. All urine excreted overnight was collected (or directly drawn from the bladder via cystocentesis) into a sterile container containing 5 ml of thymol (1%) to prevent bacterial growth. Urine was subsequently assayed by high-performance liquid chromatography, as described previously (23). Briefly, urine samples were deionized and centrifuged. The resulting supernatant was separated on an anion exchange column by high-performance liquid chromatography. Peak identification was determined by comparison to authentic standards, and quantitation was performed by comparing to known linear standards at multiple concentrations. Small bowel permeability was measured as the fractional excretion of lactulose to mannitol in urine.

Immunodetection in tissue sections

Immunohistochemical and immunofluorescent labeling was performed using 6-μm paraffin-embedded serial feline ileum sections and 8-μm epon-embedded serial human duodenal sections, respectively, prepared as described previously (24). Briefly, feline ileum and human duodenal sections were deparaffinized and hydrated using decreasing concentrations of ethanol. Antigen retrieval was performed by boiling the slides in 0.01 M trisodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 10 min. Sections were blocked in PBS containing 10% normal goat serum (NGS), 2% BSA, and 0.1% Triton X-100 overnight at 4°C. Tissue sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with antibodies against feline CD3 (1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and major histocompatability complex class II (MHC class 2; 1:100; Dr. Peter Moore, University of California, Davis, CA, USA), washed in PBS, then incubated with either Cy3 or Alexa 488 conjugated goat anti-rabbit or mouse (1:500 dilution; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) for 1 h at room temperature in dark followed by repeated washing in PBS. Feline sections were mounted in Gelvatol before viewing. Human duodenal sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with antibodies against CD3ε (1:100; Abcam) and CHOP (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), washed in PBS, then incubated with biotin-conjugated goat antibodies, followed by avidin-biotin-peroxidase amplification (1:500 dilution; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 2 h at room temperature, followed by repeated washing in PBS. Subsequent immunoreactivity was detected by 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrachloride staining (Vector Laboratories). The specificity of staining was confirmed by omitting the primary antibody. Human and feline tissue sections were also stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Briefly, sections were deparaffinized and hydrated using decreasing concentrations of ethanol. After staining in hematoxylin stain (Surgipath, Richmond, IL, USA), sections were decolorized in 1% acid alcohol and then developed in ammonia. After counterstaining in eosin stain (Surgipath), slides were dehydrated in increasing amounts of alcohol and mounted. All sections were examined with a Zeiss Axioskop 2 upright microscope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Oberkochen, Germany) and a LSM510 META confocal laser-scanning microscope (Zeiss) and analyzed using LSM 5 Image Browser (Zeiss).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by Student's t test when comparing two different groups or by ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer or Bonferroni as post hoc tests, using GraphPad Instat 3.0 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Human duodenal studies

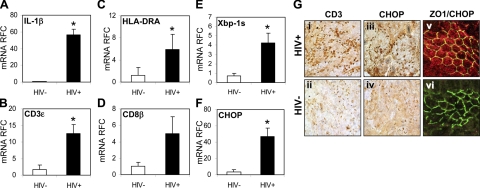

Infection and inflammation of the gut are an intrinsic component of AIDS, leading to injury of epithelial cells lining the lumen of the small and large bowels with ensuing clinical signs and symptoms (2). To investigate the mechanisms underlying damage to the small bowel, duodenal biopsies from HIV-1 seronegative (HIV−) and AIDS-defined seropositive (HIV+) persons were assessed. Transcripts encoding IL-1β (Fig. 1A), CD3ε (Fig. 1B), HLA-DRA (Fig. 1C), and CD8β (Fig. 1D) were significantly increased in samples from HIV+ persons compared to samples from HIV− persons. Xbp-1 spliced (Xbp-1s; Fig. 1E) showed increased expression, as did mRNA levels of CHOP/GADD153 (Fig. 1F). To confirm the expression of the above genes, specimens were analyzed by immunocytochemical staining, showing an increased number of CD3-immunopositive cells within the tissues from HIV+ persons (Fig. 1Gi) relative to the uninfected group (Fig. 1Gii). Given the above results of increased Xbp-1s and CHOP, CHOP immunoreactivity was also assessed at the protein level, revealing substantial immunostaining within the HIV+ samples (Fig. 1Giii). CHOP immunoreactivity was found in cells positively stained for ZO-1, a protein present on the cytoplasmic membrane surface of intercellular tight junctions (Fig. 1Gv). These results underlined the inflammation, which occurs in the gut during AIDS and is accompanied by evidence of augmented ER stress gene expression in epithelial cells.

Figure 1.

HIV-1 infection induces ER stress and immune activation in the gut. A–D) Duodenal biopsies from HIV+ patients showed elevated IL-1β (A), CD3ε (B), HLA-DRA (C), and CD8β (D) transcripts compared with HIV− patients. E, F) Levels of the ER stress markers, Xbp-1 spliced (Xbp-1s; E) and CHOP (F), were also up-regulated. G) Low levels of CD3 immunoreactivity were evident in HIV− sections (ii) compared to HIV+ sections (i), revealing lymphocyte infiltration. HIV+ sections (v) showed abundant levels of CHOP immunopositive nuclei (iii) compared to HIV− sections (iv). CHOP immunoreactive for cells also revealed positive Z0–1 staining in HIV+ sections (v), compared to HIV− sections (vi). Values are means ± se. Original view ×400. *P < 0.05; Student's t test.

Gut epithelial responses to HIV-1

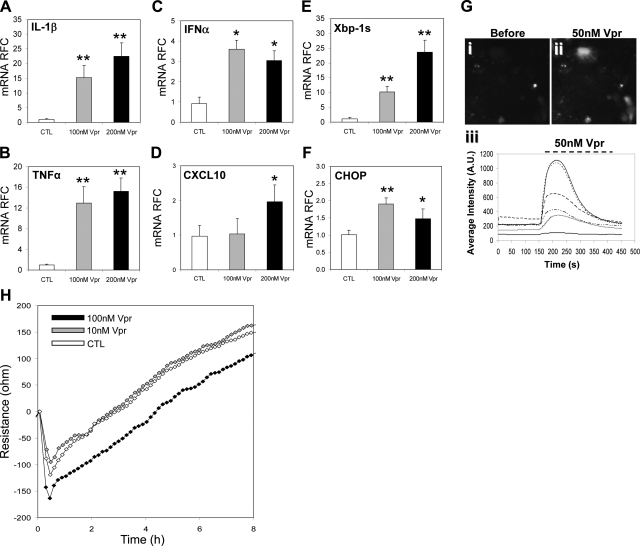

Reduced epithelial cell viability is a key feature of AIDS enteropathy associated with local inflammation, malabsorption, and increased gut permeability. To determine the direct effects of HIV-1 on epithelial cells, T84 cells (a human colonic adenocarcinoma cell line) were exposed to the HIV-1 protein, Vpr, and the cellular response was assessed. Vpr-exposed cells showed an induction of innate immune responses, as evidenced by significantly increased levels of IL-1β (Fig. 2A) TNF-α (Fig. 2B) and IFN-α (Fig. 2C), which was complemented by enhanced CXCL10 expression (Fig. 2D). These findings resembled the above observations in the human gut samples.

Figure 2.

Exposure of intestinal epithelial cells to HIV-1 Vpr results in ER stress induction and calcium activation. A–D) Vpr exposure of epithelial (T84) cells resulted in up-regulation of proinflammatory transcripts TNF-α (A), IL-1β (B), IFNα (C), and CXCL10 (D). E, F) ER stress markers XBP-1s (E) and CHOP (F) gene expression levels were also increased. G) Imaging of Fluo-8 labeled T84 cells before (i) and during (ii) Vpr exposure revealed increased intracellular fluorescence, which was confirmed by time course and fluorescence intensity changes in T84 cells (iii). H) Epithelial cell monolayer integrity was disrupted by exposure to Vpr over time, as evidenced by a decrease in resistance compared to control as determined by ECIS resistance. Values are means ± se. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; Student's t test.

Changes in calcium levels within a cell, whether from mobilization of intracellular stores or from influx through Ca2+-permeable channels, mediate several downstream signaling pathways, leading to cellular injury. To investigate this question herein, calcium responses were measured after exposure to Vpr in T84 cells, which showed a rapid and transient change in fluorescent intensity (171±45%, n=10) within 20 s after exposure to Vpr (50 nM; Fig. 2Gii) and shown graphically (Fig. 2Giii). In addition, similar to the gut specimens from HIV+ persons, cells exposed to Vpr displayed activation of XBP-1s (Fig. 2E) and CHOP (Fig. 2F) transcripts, indicating an increase in ER stress responses. To assess the biological consequences of Vpr exposure, the permeability of confluent epithelial cells was evaluated following Vpr (100 nM) application, which disclosed persistently diminished resistance (Fig. 2H). However, a change in resistance was not evident at a lower Vpr concentration (10 nM). Thus, soluble HIV-1 Vpr directly and acutely induced gut epithelial cell immune and ER stress gene expression in conjunction with altered calcium signaling, all of which was accompanied by increased permeability in the cellular monolayer.

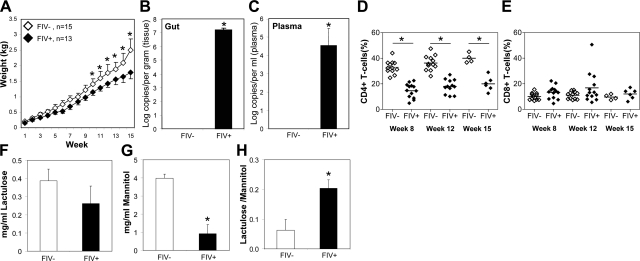

In vivo model of AIDS

While in vitro assays are informative about individual host cell responses, in vivo analyses can often provide a broader understanding of the pathogenic events involving a multisystem disease like AIDS. To investigate effects of FIV infection, weight gain was recorded following infection of neonatal cats, which showed that FIV-infected (FIV+) animals failed to gain weight at the same rate as mock-infected (FIV−; Fig. 3A). Mean viral load in the gut of FIV+ animals was high (≈7 log10/g; Fig. 3B) and was also evident in plasma (≈4.5 log10/ml; Fig. 3C). At 8, 12, and 15 wk postinfection, FIV+ animals showed significantly lower CD4+ T-lymphocyte levels compared with FIV− animals (Fig. 3D). Conversely, CD8+ T-lymphocyte levels did not differ significantly in FIV+ animals compared to FIV− animals (Fig. 3E). As there were changes observed in gut epithelial cell monolayers following exposure to the HIV-1 protein Vpr, the in vivo permeability in the present model was examined. Following oral administration of a lactulose:mannitol mixture, lactulose levels in urine did not differ between FIV+ and FIV− animals (Fig. 3F). In contrast, urine mannitol levels were significantly lower in FIV+ animals relative to the FIV− group (Fig. 3G). Mannitol is a marker of villus tip surface area, whereas lactulose is a marker of paracellular permeability. The lactulose:mannitol ratio, an indicator of paracellular permeability per unit surface area in the small intestine, was significantly higher in the FIV+ groups (Fig. 3H), implying that FIV infection increased permeability in the small intestine, likely by reducing the surface area of the villus tips. These results highlighted the effect of FIV infection on systemic variables, such as weight gain, immune status, and concurrent abundance of viral infection of gut and blood, accompanied by altered gut permeability.

Figure 3.

FIV infection causes high gut viral burden, reduced weight gain, and immunosuppression together with altered permeability. A) Weight gain was significantly reduced in FIV+ animals as compared to FIV− animals in all weeks after wk 10. B, C) Viral load measurements in gut (B) and plasma (C) confirmed FIV infection. D, E) FIV infection reduced CD4+ T-cell levels in blood of infected animals at 8, 12, and 15 wk postinfection (D), compared to uninfected animals with minimal change in CD8+ T-cell levels (E). F, G) Analysis of lactulose and mannitol levels in excreted urine revealed that FIV+ animals exhibit a general malabsorption of nutrients, as indicated by low levels of both lactulose (F) and mannitol (G) compared to FIV− animals. H) FIV+ animals exhibited a high lactulose/mannitol ratio in the urine, indicative of increased permeability across the intestinal wall and disrupted integrity. Values are means ± sd. *P < 0.05; Student's t test.

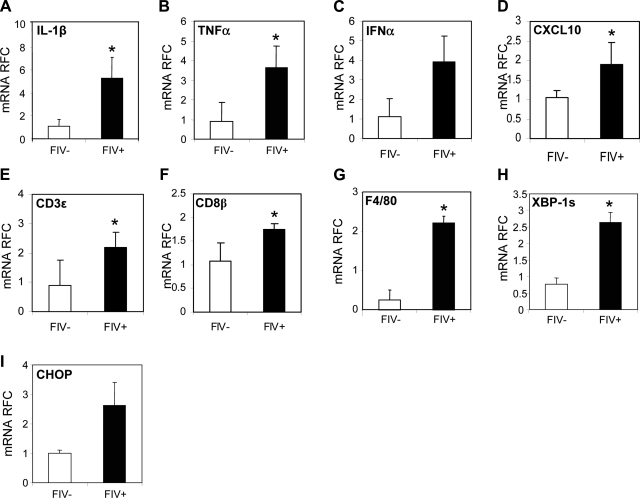

In vivo host immune gut responses

Since an accentuated host immune response is a key aspect of AIDS-related enteropathy, host immune gene changes were analyzed in the ileum from the present in vivo model. These studies showed that IL-1β (Fig. 4A), TNF-α (Fig. 4B), IFN-α (Fig. 4C), CXCL10 (Fig. 4D), CD3ε (Fig. 4E), CD8β (Fig. 4F), and F4/80 (a myeloid cell activation marker; Fig. 4G) transcript levels were significantly increased in the ileum of FIV+ animals compared to FIV− animals. Likewise, XBP-1s (Fig. 4H) and CHOP (Fig. 4I) transcript levels were also increased in the gut of FIV+ animals relative to the FIV− animals. These observations paralleled findings in HIV/AIDS duodenal samples (Fig. 1), as well as in epithelial cells exposed to HIV-1 Vpr (Fig. 2).

Figure 4.

Altered host gene expression in the gut of FIV+ animals. A–D) Proinflammatory transcript levels of IL-1β (A), TNF-α (B), IFNα (C), and CXCL10 (D) were increased in FIV+ animals in gut compared to FIV− animals. E–G) Similarly, markers of immune cell infiltration and activation, CD3ε (E), CD8β (F), and F4/80 (G), were also increased in FIV+ animals. H, I) Transcript levels of ER stress markers XBP-1s (H) and CHOP (I) were also elevated in FIV+ animals. Values are means ± se. *P < 0.05; Student's t test.

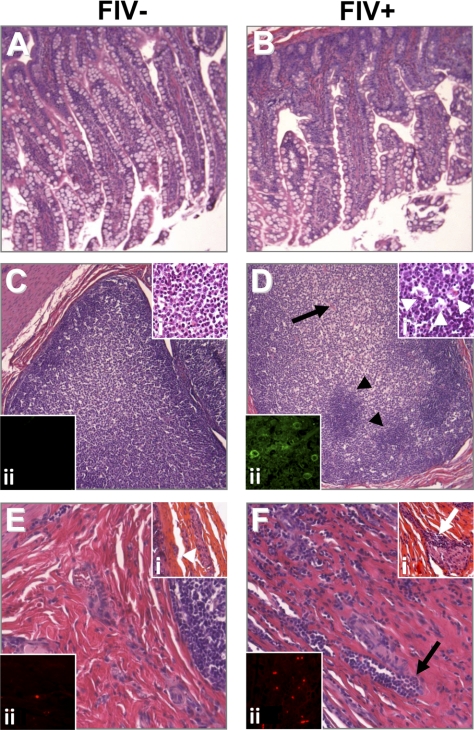

In vivo pathological changes in gut

Since pathophysiological and molecular changes were apparent in the present AIDS model, the morphological correlates of these perturbations were examined. Histochemical staining of gut sections from FIV− (Fig. 5A) and FIV+ animals (Fig. 5B) showed areas of reduced epithelial cell density coupled with atrophied villi from the FIV+ animals (Fig. 5B). In Peyer's patches from FIV− animals, numerous mononuclear cells were evident (Fig. 5C), which were uniform in appearance (Fig. 5Ci). In contrast, Peyer's patches in the FIV+ animals displayed heterogenous cellularity (Fig. 5D) and were characterized by the presence of phagocytic Tingle body macrophages (Fig. 5Di). In addition, feline MHC class II immunoreactivity was abundant on gut myeloid-resembling cells of FIV+ animals (Fig. 5Dii) but was minimally detected in FIV− animals (Fig. 5Cii). Within the lamina propria, occasional lymphocytes were observed in FIV− animals (Fig. 5E), accompanied by preserved Meissner's plexi (Fig. 5Ei). However, in the gut submucosa from FIV+ animals, numerous infiltrating lymphocytes were observed (Fig. 5F). This finding was accompanied by clusters of lymphocytes invading the Meissner's plexus ganglia and loss of associated neurons (Fig. 5Fi). Moreover, the infiltrating lymphocytes in the gut of FIV+ animals were CD3 immunopositive (Fig. 5Fii), suggesting that T-lymphocyte infiltration was a component of the disease process.

Figure 5.

FIV infection causes inflammation in the gut and results in disruption of intestinal mucosa. A, B) Epithelial cells in FIV− animals (A) revealed a more regular and elongated phenotype compared to FIV+ tissue (B), which appeared shortened and irregular. C, D) Peyer's patches in FIV− animals (C) showed a uniform cellular composition compared to FIV+ animals (D, arrowheads), which exhibited a disrupted, irregular appearance (arrow). i) Higher magnification of the Peyer's patches in FIV− (Ci) and FIV+ (Di) animals revealed abnormal tissue structure in FIV+ animals (arrowheads). ii) Immunofluorescence staining of feline MHC class II revealed an increased population of immunoreactive cells in FIV+ animals (Dii) compared to FIV− animals (Cii). E, F) FIV+ animals exhibited extensive leukocyte infiltration within the lamina propria and Meissner's plexus (F) compared to FIV− animals (E). i) This infiltration was highlighted by comparing FIV− (Ei, arrowhead) and FIV+ animals (Fi, arrow). ii) CD3ε immunoreactivity was highly abundant in FIV+ animals (Fii) compared to FIV− animals (Eii). Original view ×400.

DISCUSSION

The present studies used a multiplatform experimental strategy, including human ex vivo biopsy samples, an in vitro cell culture model, and an in vivo feline lentivirus model to investigate the mechanisms by which AIDS enteropathy develops. In each phase of this series of experiments, ER stress in gut epithelial cells was demonstrated, accompanied by prototypic inflammation and enteropathic damage. Notably, local inflammation mediated by infiltrating lymphocytes and activated macrophages, which expressed proinflammatory cytokines, was a key feature of AIDS enteropathy. In fact, a viral protein, HIV-1 Vpr acutely (and directly) induced innate immune activation, calcium signaling, and ER stress in gut epithelial cells, underscoring the capacity of a lentivirus protein to instigate enteropathic mechanisms through its direct actions. Finally, these studies emphasize the potential effect of acute ER stress with ensuing inflammation in diseases of the gut, suggesting these pathogenic mechanisms might be relevant to other inflammatory bowel diseases.

Markers of ER stress and inflammation were up-regulated in the gut during lentiviral infection, which was complemented by a direct induction of calcium signaling and ER stress genes by the soluble viral protein, Vpr. Vpr is critical for viral infection of macrophages but also modulates cell cycle and survival (25). Vpr is encoded by all strains of HIV, but there are also orthologs in other lentiviruses. In fact, FIV encodes an open reading frame, ORF-A, which is located in a similar position within the FIV genome to that of Vpr within HIV-1 and exerts comparable actions (26). Although the receptor for ORF-A remains unknown, the receptor for Vpr has been posited to be the glucocorticoid receptor, providing a direct link to modulating inflammation and cell survival, but the underlying pathogenic pathways remain to be defined. Taken together, the consistent findings of ER stress and inflammation in both HIV- and FIV-infected gut tissues was not surprising, given the similarity in the viruses' structure and biology, but also point to Vpr as a potential virulence factor in AIDS enteropathy. An alternative explanation for the present findings of gut-associated ER stress and inflammation might be a concurrent opportunistic infection mediating these host responses. However, on the basis of histopathological analyses, in the present studies, gut samples from humans were not coinfected with other pathogens. Likewise, the present feline colony was raised in specific pathogen-free conditions and did not display differing bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA levels in plasma, depending on FIV infection status (27), precluding roles for concurrent bacterial sepsis or microbial translocation in the present model. Indeed, the latter assumption was supported by histopathological studies of the experimental animals' ileum.

The unfolded protein response is a homeostatic mechanism by which cells handle aggregation of misfolded or unfolded proteins but can progress to ER stress depending on the circumstances (28). The ER is a multifunctional organelle that is involved in protein folding, lipid biosynthesis, and calcium homeostasis (29). There are 3 principal ER stress cascade initiators: PRKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), inositol requirement enzyme 1 (IRE-1), and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF-6). IRE-1 has kinase and endoribonuclease activities, but its chief function in ER stress is to cleave an intron in premature transcript of X-box binding protein (XBP-1) to yield a mature spliced XBP-1 transcript that regulates transcription, including MHC class II expression (30). In fact, XBP-1s represents the prototype in terms of ER stress markers and was induced in all models examined in these current studies. Phosphorylated eIF-2α is also activated during ER stress and augments transcription of specific chaperones, such as CHOP, which can stimulate the expression of ERAD component genes and in some instances leads to cellular apoptosis. Like Xbp-1s, CHOP was increased in all experimental platforms but was immunodetected in epithelial cells in human gut specimens, which was complemented by villus atrophy and goblet cell loss. Nuclear factor κ-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) is a key transcriptional regulator and on translocation to the nucleus, it activates transcription of several inflammatory genes. The precise mechanism by which NF-κB initiates inflammation through ER stress remains unclear; however, experiments using calcium chelators and antioxidants indicate that reactive oxygen species are also a signal for ER-associated NF-κB induction during ER stress. Likewise metabolic factors and calcium homeostasis also influence ER stress, resulting in inflammation (31). While many diseases involve inflammation, it is important for ER stress to avoid pathogenic protein aggregation but conversely, control of ER stress is also crucial to avoid inflammation.

Inflammation represents a major feature of lentivirus infections involving both innate and adaptive immune activation. Given that the gut contains the largest quantity of lymphoid tissue within the body, inflammation in proximity to the gut is to be expected, as has been reported in HIV and SIV infections (32). The current data support this notion in that IFN-α and HLA-DR transcript levels were increased in vitro and in vivo, and in both HIV and FIV-infected gut specimens, there was evidence of lymphocyte infiltration, suggestive of innate and adaptive immune activation, respectively. The relative contribution of each arm of immunity to gut damage in lentivirus enteropathy remains unknown, but compelling evidence implies overexpression of innate immune molecules might be a critical determinant of systemic lentivirus virulence (33). However, the induction by inflammation of ER stress might also be driven by other stressors within the gut; for example, leukocyte infiltration of Meissner's plexus (Fig. 5) could induce neurohumoral stress responses leading to excess production of 6-OH-dopamine and other neurotoxins. In fact, injury to the human and feline nervous system by HIV and FIV, respectively, is well established and can readily contribute to substantial organ dysfunction (34).

The present observations of lentivirus infections mediating ER stress in conjunction with inflammation and epithelial loss as a pathogenic mechanism raises the possibility of therapeutic targeting of ER stress. The use of protease inhibitors as antiretroviral therapies might be contraindicated in the setting of AIDS enteropathy. Conversely, the use of ER stress inhibitors such as rebamipide (35) and specific proteases might offer therapeutic benefits. Similarly, suppression of inflammation and the generation of free radicals by gut-specific drugs could improve clinical outcomes. The experimental models described presently provide relevant and manageable models of AIDS enteropathy, which could be utilized in future studies of pathogenesis and potential therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Naomi Hotte, Claire Arrieta, and Amber Paul for their technical assistance and the staff in the University of Alberta Health Sciences Laboratory Animal Services for their support and assistance. E.A.C. and C.P. hold Canada Research Chairs (CRCs; tier 1) in Human Retrovirology and Neurological Infection and Immunity, respectively. C.P. holds an Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research senior scholarship.

These studies were supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (C.P., K.M.) and the U.S. National Institutes of Health (National Institute for Mental Health; C.P.). None of the authors have commercial interests or activities related to the contents of the present manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Shacklett B. L., Beadle T. J., Pacheco P. A., Grendell J. H., Haslett P. A., King A. S., Ogg G. S., Basuk P. M., Nixon D. F. (2000) Characterization of HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes expressing the mucosal lymphocyte integrin CD103 in rectal and duodenal lymphoid tissue of HIV-1-infected subjects. Virology 270, 317–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dandekar S. (2007) Pathogenesis of HIV in the gastrointestinal tract. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 4, 10–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brenchley J. M., Douek D. C. (2008) The mucosal barrier and immune activation in HIV pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 3, 356–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brenchley J. M., Douek D. C. (2008) HIV infection and the gastrointestinal immune system. Mucosal Immunol. 1, 23–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li Q., Estes J. D., Duan L., Jessurun J., Pambuccian S., Forster C., Wietgrefe S., Zupancic M., Schacker T., Reilly C., Carlis J. V., Haase A. T. (2008) Simian immunodeficiency virus-induced intestinal cell apoptosis is the underlying mechanism of the regenerative enteropathy of early infection. J. Infect. Dis. 197, 420–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sankaran S., George M. D., Reay E., Guadalupe M., Flamm J., Prindiville T., Dandekar S. (2008) Rapid onset of intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction in primary human immunodeficiency virus infection is driven by an imbalance between immune response and mucosal repair and regeneration. J. Virol. 82, 538–545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Batman P. A., Kotler D. P., Kapembwa M. S., Booth D., Potten C. S., Orenstein J. M., Scally A. J., Griffin G. E. (2007) HIV enteropathy: crypt stem and transit cell hyperproliferation induces villous atrophy in HIV/microsporidia-infected jejunal mucosa. AIDS 21, 433–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kotler D. P. (2005) HIV infection and the gastrointestinal tract. AIDS 19, 107–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kaser A., Blumberg R. S. (2010) Endoplasmic reticulum stress and intestinal inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 3, 11–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Elder J. H., Sundstrom M., de Rozieres S., de Parseval A., Grant C. K., Lin Y. C. (2008) Molecular mechanisms of FIV infection. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 123, 3–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Willett B. J., Flynn J. N., Hosie M. J. (1997) FIV infection of the domestic cat: an animal model for AIDS. Immunol. Today 18, 182–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bukrinsky M., Adzhubei A. (1999) Viral protein R of HIV-1. Rev. Med. Virol. 9, 39–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Snyder A., Alsauskas Z. C., Leventhal J. S., Rosenstiel P. E., Gong P., Chan J. J., Barley K., He J. C., Klotman M. E., Ross M. J., Klotman P. E. (2010) HIV-1 viral protein r induces ERK and caspase-8-dependent apoptosis in renal tubular epithelial cells. AIDS 24, 1107–1119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhu Y., Vergote D., Pardo C., Noorbakhsh F., McArthur J. C., Hollenberg M. D., Overall C. M., Power C. (2009) CXCR3 activation by lentivirus infection suppresses neuronal autophagy: neuroprotective effects of antiretroviral therapy. FASEB J. 23, 2928–2941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Power C., Buist R., Johnston J. B., Del Bigio M. R., Ni W., Dawood M. R., Peeling J. (1998) Neurovirulence in feline immunodeficiency virus-infected neonatal cats is viral strain specific and dependent on systemic immune suppression. J. Virol. 72, 9109–9115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gill M. J., Sutherland L. R., Church D. L. (1992) Gastrointestinal tissue cultures for HIV in HIV-infected/AIDS patients. The University of Calgary Gastrointestinal/HIV Study Group. AIDS 6, 553–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Johnston J. B., Silva C., Hiebert T., Buist R., Dawood M. R., Peeling J., Power C. (2002) Neurovirulence depends on virus input titer in brain in feline immunodeficiency virus infection: evidence for activation of innate immunity and neuronal injury. J. Neurovirol. 8, 420–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhu Y., Jones G., Tsutsui S., Opii W., Liu S., Silva C., Butterfield D. A., Power C. (2005) Lentivirus infection causes neuroinflammation and neuronal injury in dorsal root ganglia: pathogenic effects of STAT-1 and inducible nitric oxide synthase. J. Immunol. 175, 1118–1126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kennedy J. M., Hoke A., Zhu Y., Johnston J. B., van Marle G., Silva C., Zochodne D. W., Power C. (2004) Peripheral neuropathy in lentivirus infection: evidence of inflammation and axonal injury. AIDS 18, 1241–1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boven L. A., Noorbakhsh F., Bouma G., van der Zee R., Vargas D. L., Pardo C., McArthur J. C., Nottet H. S., Power C. (2007) Brain-derived human immunodeficiency virus-1 Tat exerts differential effects on LTR transactivation and neuroimmune activation. J. Neurovirol. 13, 173–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Power C., Henry S., Del Bigio M. R., Larsen P. H., Corbett D., Imai Y., Yong V. W., Peeling J. (2003) Intracerebral hemorrhage induces macrophage activation and matrix metalloproteinases. Ann. Neurol. 53, 731–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Levy D. N., Refaeli Y., MacGregor R. R., Weiner D. B. (1994) Serum Vpr regulates productive infection and latency of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91, 10873–10877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meddings J. B., Gibbons I. (1998) Discrimination of site-specific alterations in gastrointestinal permeability in the rat. Gastroenterology 114, 83–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tsutsui S., Vergote D., Shariat N., Warren K., Ferguson S. S., Power C. (2008) Glucocorticoids regulate innate immunity in a model of multiple sclerosis: reciprocal interactions between the A1 adenosine receptor and beta-arrestin-1 in monocytoid cells. FASEB J. 22, 786–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Planelles V., Benichou S. (2009) Vpr and its interactions with cellular proteins. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 339, 177–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gemeniano M. C., Sawai E. T., Sparger E. E. (2004) Feline immunodeficiency virus Orf-A localizes to the nucleus and induces cell cycle arrest. Virology 325, 167–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maingat F., Viappiani S., Zhu Y., Vivithanaporn P., Ellestad K. K., Holden J., Silva C., Power C. (2010) Regulation of lentivirus neurovirulence by lipopolysaccharide conditioning: suppression of CXCL10 in the brain by IL-10. J. Immunol. 184, 1566–1574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang K., Kaufman R. J. (2008) From endoplasmic-reticulum stress to the inflammatory response. Nature 454, 455–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kaser A., Blumberg R. S. (2009) Endoplasmic reticulum stress in the intestinal epithelium and inflammatory bowel disease. Semin. Immunol. 21, 156–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Malhotra J. D., Kaufman R. J. (2007) The endoplasmic reticulum and the unfolded protein response. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 18, 716–731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gargalovic P. S., Gharavi N. M., Clark M. J., Pagnon J., Yang W. P., He A., Truong A., Baruch-Oren T., Berliner J. A., Kirchgessner T. G., Lusis A. J. (2006) The unfolded protein response is an important regulator of inflammatory genes in endothelial cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26, 2490–2496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Orandle M. S., Veazey R. S., Lackner A. A. (2007) Enteric ganglionitis in rhesus macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 81, 6265–6275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mogensen T. H., Melchjorsen J., Larsen C. S., Paludan S. R. (2010) Innate immune recognition and activation during HIV infection. Retrovirology 7, 54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zink M. C., Laast V. A., Helke K. L., Brice A. K., Barber S. A., Clements J. E., Mankowski J. L. (2006) From mice to macaques—animal models of HIV nervous system disease. Curr. HIV Res. 4, 293–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ishihara T., Tanaka K., Tashiro S., Yoshida K., Mizushima T. (2010) Protective effect of rebamipide against celecoxib-induced gastric mucosal cell apoptosis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 79, 1622–1633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]