Abstract

Clinical question:

What are the most effective treatment(s) for mild, moderate, severe, and hormonally driven acne?

Results:

Mild acne responds favorably to topical treatments such as benzoyl peroxide, salicylic acid, and a low-dose retinoid. Moderate acne responds well to combination therapy comprising-topical benzoyl peroxide, antibiotics, and/or retinoids, as well as oral antibiotics in refractory cases and oral contraceptive pills for female acne patients. Severe nodulocystic acne vulgaris responds best to oral isotretinoin therapy. In female patients with moderate to severe acne, facial hair, loss of scalp hair and irregular periods, polycystic ovarian syndrome should be considered and appropriate treatment with hormonal modulation given. Adjunctive procedures can also be considered for all acne patients.

Implementation:

Pitfalls to avoid when treating acne: treatment of acne in women of child-bearing age; familiarization of all acne treatments in order to individualize management for patients; indications for specialist referral.

Keywords: acne vulgaris, benzoyl peroxide, retinoids, antibiotics, light and laser therapy, photodynamic therapy, photopneumatic therapy, chemical peels

Acne vulgaris

Definition:

Acne vulgaris is a common multifactorial inflammatory condition of the pilo sebaceous follicle.

Classification:

Based on the severity: mild, moderate, or severe, and the types of lesions present: comedones, papules, pustules, and nodules as well as the presence or absence of scarring.

Pathogenesis:

Four factors: follicular epidermal hyper proliferation, surplus of sebum production, inflammation, and the concentration and activity of Propionibacterium acnes.1

Incidence:

Mean age for the start of acne in girls is 11 years and boys 12 years, as concluded by several studies from multiple countries,2 with a peak at 15 to 18 years.3 Acne prevalence in the adolescent community is estimated at 70% to 87%.2 In one large community based study in the United Kingdom, physiologic facial acne was seen in 54% of the adult population (ages 25 to 58 years), with clinical acne estimated at 3% in adult men and 12% in adult women.4

Assessment:

Note areas involved (face, neck, chest, and/or back), type and number of acne lesions, presence/absence and tendency for scarring, possible hormonal influence relating to acne flare, and the psychological role acne may be playing in the patient’s life.5 In females with moderate to severe acne, a history of facial hair, loss of scalp hair, and irregular periods should be noted. In males, use of anabolic steroids should be ascertained.

Outcomes:

Patients seek improvement of acne lesions, with the hope of full clearing. Relapse is common. A patient specific course of therapy is needed, and may require trials of different medications and procedures until an optimal regimen is found.

Economics:

US$100 million per year is spent on over-the-counter treatments for acne, while the price of acne likely exceeds US$1 billion per year in the United States.6

Treatment:

Goal of therapy is to target the four steps contributing to the pathogenicity of acne, while selecting a treatment based on the patient’s skin type and acne severity.

Consumer summary:

Acne is a common skin complaint which can affect both genders at all ages. Treatment is based on the severity and appearance of acne, and consists of various topical and oral medications, as well as medical procedures.

The evidence

What treatments are most effective for mild to moderate acne?

Search sources: PubMed, Cochrane Library, Medline, clinical evidence.

Search strategy: Keywords used in this search include “mild acne”, “moderate acne”, “benzoyl peroxide”, “topical retinoids and acne”, “topical acne antibiotics”, and “oral acne antibiotics”. Articles used were limited to systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Search limits include a publication date 1995 to present and English language. The systematic review and meta-analyses were selected based on evaluations of several current treatments for mild and moderate acne. RCTs were chosen based on investigator-blind or double-blind, randomized studies with at least an 11-week treatment duration, as well as documentation of acne severity, and reduction of total, inflammatory, and/or noninflammatory lesions. Two RCTs listed below (Thiboutot et al9 and Ozolins et al21) were also analyzed in the systematic review.

Table 1.

RCTs of benzoyl peroxide and topical retinoids used to treat acne after 12 weeks

| Reference | No of patients | Acne severity | Treatment | Reduction of inflammatory lesions, % | P value | Reduction of noninflammatory lesions, % | P value | Total reduction of lesions, % | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thiboutot et al9 | adapalene gel 0.3% = 258 adapalene gel 0.1% = 261 vehicle = 134 |

moderatea | adapalene gel 0.3% (1) vs adapalene gel 0.1% (2) vs gel vehicle (3) | 62.5 58 47 |

(1) vs (2) = 0.015 (2) vs (3) < 0.001 |

52 43 29 |

(1) vs (2) = 0.061 (2) vs (3) < 0.001 |

56 48 36 |

(1) vs (2) = 0.02 (2) vs (3) < 0.001 |

| Tan et al10 | adapalene-BPO = 983 adapalene = 986 BPO = 979 vehicle = 907 |

moderatea | adapalene 0.1%/BPO 2.5% (1) vs adapalene 0.1% (2) vs BPO 2.5% (3) vs vehicle (4) | 66 52 57 38 |

(1) vs (2, 3, 4) < 0.001 |

58 48 45 38 |

(1) vs (2, 3, 4) < 0.05 |

59 47 46 33 |

(1) vs (2, 3, 4) < 0.05 |

| Shalita et al11 | adapalene = 149 tretinoin = 139 |

moderatea | adapalene gel 0.1% vs tretinoin gel 0.025% | 48 38 |

0.06b | 46 33 |

0.02b | 49 37 |

< 0.01b |

| Cunliffe et al12 (meta-analysis of 5 trials) |

adapalene = 450 tretinoin = 450 |

mild-moderate | adapalene gel 0.1% vs tretinoin gel 0.025% | 52 51 |

0.51b | 58 52 |

0.38b | 57 53 |

0.48b |

| Shalita et al13 | tazarotene = 424 vehicle = 423 |

moderatea | tazarotene 0.1% cream vs vehicle cream | 43 27 |

< 0.001b | 44 24 |

< 0.001b | 43 23 |

< 0.001b |

| Shalita et al14 | tazorotene = 86 adapalene = 87 |

mild-moderatea | tazarotene 0.1% cream vs adapalene 0.1% cream | 62 50 |

NS | 68 36 |

≤ 0.001b | n/a n/a |

|

| Thiboutot et al15 | tazorotene = 86 adapalene = 86 |

moderatea | tazorotene 0.1% gel vs adapalene 0.3% gel | 59 67 |

0.066b | 55 55 |

0.307b | 57 61 |

0.515b |

| Tanghetti et al16 | tazarotene = 90 adapalene = 90 |

moderate-severe | tazortene 0.1% cream vs adapalene 0.3% gel | 63 48 |

0.274b | 68 60 |

0.107b | 63 56 |

0.221b |

Notes:

severity estimated from lesion counts or global grades;

between group comparisons.

Abbreviations: BPO, benzoyl peroxide; n/a, data not reported; NS, not significant.

Table 3.

RCT of five antimicrobial treatment regimens for 18 weeks duration

| Reference | No of patients | Acne severity | Treatment | Treatment difference for patient’s perception of improvement, % (95% CI) | Odds ratio, (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ozolins et al21 | oxytetracycline = 131 | mild-moderate | 500 mg oxytetracycline po bid (1) vs | 2 vs 1 = −1.2 (−13.3–10.9) | 0.95 (0.58–1.55) |

| minocycline = 130 | 100 mg minocycline po daily (2) vs | 4 vs 1 = 11.1 (−0.7–22.9) | 1.64 (0.98–2.74) | ||

| topical 5% BPO = 130 | topical 5% BPO bid (3) vs | 4 vs 2 = 12.3 (0.4–24.2) | 1.74 (1.04–2.90) | ||

| topical 5% BPO + 3% | topical 5% BPO + 3% | 5 vs 4 = −3.5 (−15.2–8.2) | 0.84 (0.50–1.42) | ||

| erythromycin = 127 | topical erythromycin bid (4) vs | 3 vs 1 = 5.0 (−7.0–17.0) | 1.19 (0.72–1.96) | ||

| topical 2% erythromycin in AM + topical 5% BPO in PM (5) | 3 vs 2 = 6.2 (−5.8–18.2) | 1.26 (0.76–2.08) | |||

| topical 2% erythromycin + 5% BPO = 131 |

3 vs 4 = −6.1 (−17.9–5.7) | 0.72 (0.43–1.21) |

Abbreviations: AM, morning; PM, evening; BPO, benzoyl peroxide; bid, twice daily; CI, Confidence interval; po, by mouth.

The systematic review7 looked at the efficacies and potential benefits of various topical and oral treatments for all stages of acne, and included 67 systematic reviews, RCTs, or observational studies. All medications were compared to placebo, except for oral erythromycin which was compared to oral doxycycline and oral tetracycline, as no placebo studies were found at the time of search. Results showed that benzoyl peroxide is effective as a first-line treatment for mild to moderate acne as measured by the reduction in total lesion counts. If acne does not significantly improve, tretinoin or adapalene are effective treatment options as both medications showed a reduction in noninflammatory and inflammatory lesion counts. Topical antibiotics (clindamycin and erythromycin) are an effective treatment for predominance of inflammatory lesions in mild to severe acne, and can be combined with a regimen that contains topical benzoyl peroxide, tretinoin, and/or adapalene. Evidence was lacking as to the success of oral antibiotics in treating acne, but is recommended for moderate acne patients whose acne severity has not been adequately reduced by the above topical treatments. Oral erythromycin demonstrated a similar efficacy to oral tetracycline in total lesion count reduction. Oral doxycycline also showed a similar effectiveness as other oral antibiotics. One crossover RCT reported a statistically significant reduction (P = 0.001) in inflammatory lesions versus placebo after 4 weeks with 100 mg daily of oral doxycycline.

The meta-analyses8 reviewed 23 studies of topical nonretinoid combination acne treatments in comparison to the corresponding single therapies in 7309 patients: 5% benzoyl peroxide +2% salicyclic acid, 2.5% to 5% benzoyl peroxide +1% to 1.2% clindamycin, 5% benzoyl peroxide, and 1% to 1.2% clindamycin. Acne severity was not specifically stated in the analysis results; however lesion counts were included and are most consistent in patients with moderate acne. In short, combination treatments offer the most favorable results in the reduction of acne lesions compared to the corresponding single therapies. Results showed that 5% benzoyl peroxide +salicylic acid had the highest effectiveness in the reduction of lesions at 2 to 4 weeks compared to the other 3 treatments; however, benzoyl peroxide + clinamycin was equally as effective as benzoyl peroxide + salicyclic acid after 10 to 12 weeks. Mean percentage reduction in inflammatory lesion counts after 10 to 12 weeks was: benzoyl peroxide +salicyclic acid = 51.8%, benzoyl peroxide +clindamycin = 55.6%, benzoyl peroxide = 43.7%, clindamycin = 45.9%, and placebo = 26.8%. Mean percentage reduction in noninflammatory lesions after 10 to 12 weeks was: benzoyl peroxide +salicyclic acid = 47.8%, benzoyl peroxide +clindamycin = 40.3%, benzoyl peroxide =30.9%, clindamycin =32.6%, and placebo =17%.

Conclusions

In the treatment of mild acne, benzoyl peroxide is an effective first-line treatment. If results are unsatisfactory, topical tretinoin or adapalene should be added.

In moderate acne, combination therapy has shown the most favorable results and typically consists of a regimen including benzoyl peroxide, topical antibiotics, and a topical retinoid (tretinoin, adapalene, or tazorotene). Tretinoin, adapalene, and tazorotene demonstrate similar effectiveness in the reduction of inflammatory, noninflammatory, and total lesion counts after 12 weeks of treatment. Oral antibiotics may be tried for patients with a predominance of inflammatory lesions who have not responded favorably to the above topical treatments.

What treatments are most effective for severe acne?

Search sources: PubMed, Cochrane Library, Medline, clinical evidence.

Search strategy: Keywords used include “severe acne”, “cystic acne”, “conglobate acne”, “oral isotretinoin and acne”, and “systemic isotretinoin and acne”. Articles used were limited to systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and RCTs in the English language. No limits were placed on publication date. Systematic reviews were very limited and chosen based on evaluation of current treatments for severe acne. A meta-analysis was not found at the time of search. RCTs were also very limited and selected based on double-blind, randomized studies with documentation of acne severity.

| Systematic reviews: | 1 |

| RCTs: | 2 (Table 4) |

Table 4.

RCTs of isotretinoin used to treat severe acne for 16 and 20 weeks respectively

| Reference | No of patients | Acne severity | Treatment | Reduction of inflammatory lesions, % | P value/CI | Total reduction of lesions, % | P value/CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peck et al22 | isotretinoin = 16 vehicle = 17 | severe | isotretinoin vs placebo | n/a | n/a | After 8 wks 32% decrease in cystic lesions in isotretoin group with placebo patients demonstrating a 57% increase in cystic lesions |

P < 0.001 at 1 month P < 0.008 at 2 months between isotretinoin and placebo |

| Strauss et al23 | Micronized isotretinoin = 300 isotretinoin = 300 |

severe | 0.4 mg/kg micronized isotretinoin per day without food vs 1.0 mg/kg isotretinoin per day in 2 separate doses with food | 87 90 |

95% CI = 0.885–0.989 |

89b 90b |

95% CIa = 0.899–1.011 |

Notes:

equivalence between groups;

total nodule counts.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; n/a, data not reported.

The systematic review7 stated that oral isotretinoin is more effective than placebo and tetracycline at 1 month and 24 weeks, respectively, in the reduction of lesions in severe acne patients. Only 1RCT (Peck et al22) was found in this systematic review comparing isotretinoin to placebo. Results of this study are listed in Table 4. When compared to tetracycline at 24 weeks, isotretinoin significantly reduced acne cysts (P < 0.01), and pustules and comedones (P < 0.01).

Conclusions

In cases of severe acne, oral isotretinoin is the most effective therapy. In patients who are not candidates for oral isotretinoin, topical and oral treatments as mentioned above in treatments for mild to moderate acne can be considered in the treatment regimen.

What treatments are the most successful in reducing hormonally driven acne in women?

Search sources: PubMed, Cochrane Library, Medline, clinical evidence.

Search strategy: Keywords used include “acne and spironolactone”, and “oral contraceptives and acne”. Articles used were limited to systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and RCTs in the English language. No limits were placed on publication dates. A meta-analysis was not found and systematic reviews were limited to those presented below at the time of search. RCTs were limited and selected based on double blinding, randomization, and placebo control.

| A: Spironolactone | |

| Systematic reviews: | 1 |

| RCTs: | 1 |

The systematic review conducted by Brown et al24 analyzed the role of spironolactone in hirsutism and/or acne. Most studies in this review examined only hirsutism as a treatment outcome, due to a lack of studies evaluating acne. The RCT by Muhlemann et al25 was included in this review and is summarized below. The authors concluded that there is “No evidence for effectiveness (of spironolactone) for the treatment of acne vulgaris. Studies in this area are scarce and small. Individual study data indicates some superiority of spironolactone over other drugs, but results cannot be generalized”.

A randomized double-blind trial conducted by Muhlemann et al,25 examined 200 mg daily of oral spironolactone for 12 weeks versus placebo, and showed a statistically significant improvement (P < 0.001) in spironolactone patients through the reduction of inflammatory lesions and patient perception of improvement. Photographs analyzed by 3 blinded investigators during treatment also revealed an improvement (P < 0.02).

| B: Oral contraceptive pills | |

| Systematic reviews: | 1 |

| RCTs: | 6 (Table 5) |

Table 5.

RCTs of oral contraceptive pills (OCP) in the treatment of acne after 24 weeks

| Reference | No of patients | Acne severity | Treatment | Reduction of inflammatory lesions, % | P value | Reduction of non-inflammatory lesions, % | P value | Total reduction of lesions, % | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maloney et al27 | OCP = 218 | moderate | 3 mg drospirenone/20 μg ethinyl estradiol vs placebo | 50a | < 0.001c | 42a | < 0.001c | 46 | < 0.001c |

| placebo = 213 | 35 | 28 | 31 | ||||||

| Thiboutot et al28 | OCP = 96 | moderate | 100 μg of levonorgestrel/20 μg of ethinyl estradiol vs placebo | 47 | 0.027b | 25 | 0.098b | 40 | 0.004b |

| placebo = 105 | 33 | 13.5 | 23 | ||||||

| Plewig et al29 | OCP = 251 | moderate | ethinyl estradiol 0.03 mg/chlormadinone acetate 2 mg vs placebo | 64 | < 0.05b | 55 | < 0.05b | n/a | n/a |

| placebo = 126 | 45 | 0.03c | 32 | 0.0006c | |||||

| Leyden et al30 | OCP = 185 | moderate | ethinyl estradiol 20 μg/100 μg levonorgestrel vs placebo | 32 | 0.081b | 13 | 0.0485b | 23 | 0.0045b |

| placebo = 186 | 22 | 4 | 9 | ||||||

| Lucky et al31 | OCP = 79 | moderate | ethinyl estradiol 0.035 mg/norgestimate 0.180, 0.215, or 0.250 mg vs placebo | 62 | 0.0001c | 43 | 0.0003c | 53 | 0.0001c |

| placebo = 81 | 39 | 13.6 | 27 | ||||||

| Palombo-Kinne et al32 | EE/DNG = 525 | mild–moderate | ethinylestradiol 0.030 mg/dienogest 2 mg vs ethinylestradiol 0.035 mg/cyproterone acetate 2 mg vs placebo |

66 | < 0.05 EE/DNG vs placebo and non-inferiority of EE/DNG to EE/CPA | n/a | n/a | 55 | < 0.05 EE/DNG vs placebo and non-inferiority of EE/DNG to EE/CPA |

| EE/CPA = 537 | 65 | 54 | |||||||

| placebo = 264 | 49.5 | 39 |

Notes:

data estimated from graph;

between group comparisons;

mean relative difference to baseline.

Abbreviations: CPA, cyproterone acetate; DNG, dienogest; EE, ethinylestradiol; n/a, data not reported.

The systematic review conducted by Arowojolu et al26 examined 25 trials of combined oral contraceptive pills (COCs) versus placebo and various hormone regimens in the treatment of female acne patients. In summary, “The four COCs evaluated in placebo-controlled trials are effective in reducing inflammatory and noninflammatory facial acne lesions. Few important differences were found between COC types in their effectiveness for treating acne”. Of these differences, COCs containing chlormadinone acetate or cyproterone acetate fair better than those containing levonorgestrel in reducing acne severity, but this observation is based on a small selection of data. Four studies listed in the review are also listed below in the RCTs.

Conclusion

In women with moderate to severe acne or acne refractory to treatment, placement on a combined oral contraceptive pill with or without spironolactone offers significant relief and reduction of acne lesions. More studies are needed to fully evaluate the potential benefit of spironolactone in improving acne.

Nontraditional treatments in acne – are they effective?

Search sources: PubMed, Cochrane Library, Medline, clinical evidence.

We chose to focus on three popular areas of adjunctive treatments for mild–severe acne vulgaris: light, laser and photodynamic therapy (light therapy with a photosensitizer), photopneumatic therapy (light with vacuum therapy), and chemical peels.

A: Light, laser, and photodynamic therapy (PDT)

Search strategy: Keywords used included “acne and photodynamic therapy”, and “light and laser therapies and acne vulgaris”. Papers were limited to meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and RCTs in the English language. No meta-analysis was found at the time of search. RCTs were chosen based on controlled, randomized studies, and at least investigator-blinding. All RCTs focused on facial acne, except for one study (Barolet and Boucher)35 involving back and facial acne.

| Systematic reviews: | 2 |

| RCTs: | 5 (Table 6) |

Table 6.

RCTs for PDT with aminolevulinic acid therapy (ALA) and/or methyl aminolavulinate (MAL)

| Reference | No of patients | Treatment | Outcome measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barolet and Boucher35 | 10 | split face or back: pre-treatment with IR LED (970 nm) + ALA + PDT LED (630 nm) vs ALA + PDT LED (630 nm) | reduction of inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions | 73% reduction in IR pre-treated side vs 38% reduction on control side after 4 weeks, P < 0.0001; also significant decrease in non-inflammatory lesions with IR pre-treatment, P = 0.037 |

| Wiegell and Wolf36 | 15 | split face: ALA-PDT vs MAL-PDT | reduction of inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions | 59% decrease in inflammatory lesions after 12 weeks with both treatments; no significant change in percent reduction of inflammatory lesions among the 2 treatments, P = 0.455; no significant difference in reduction of non-inflammatory lesions seen in both groups, P = 0.6355 |

| Wiegell and Wolf37 | 21 | full face: MAL + PDT vs control | reduction of inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions | 68% reduction with MAL + PDT vs no difference in control after 12 weeks, P = 0.0023; no reduction in non-inflammatory lesions was seen |

| Horfelt et al38 | 30 | split face: MAL + PDT vs placebo cream + PDT | reduction of inflammatory and non-inflammatory lesions | MAL + PDT resulted in 54% median reduction of inflammatory lesions vs 20% with placebo cream + PDT after 12 weeks, P = 0.0006; no significant difference found in reduction of non-inflammatory lesions between the two groups; P = 0.6875 for open comedones; P = 1.00 for closed comedones |

| Orringer et al39 | 44 | split face: ALA + PDL vs control | reduction of inflammatory lesions | statistically significant decrease in inflammatory lesions in ALA + PDL group at 10 weeks (P = 0.01); effect was no longer seen at 16 weeks |

Abbreviations: IR, infared radiation; LED, light emitting diode; PDT, photodynamic therapy; PDL, pulsed-dye laser.

Hamilton et al33 reviewed light therapy (13 trials) and PDT (12 trials) in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Acne severity in most trials was mild to moderate. Limits include a small sample size in many of the trials as well as questionable randomization and at least investigator-blinding methods. Light studies examined yellow, blue, red, and blue-red light as well as infrared radiation. In comparison to placebo, green and yellow light showed none to a minimal difference in acne improvement, and infrared radiation showed some improvement in comedones in one study and an improvement in mean lesion counts in another. The most favorable light therapy results were shown with red, blue, and blue-red light, demonstrating a statistically significant improvement (P < 0.05) in total or inflammatory lesion counts in 3 studies included in this review. PDT compared to light therapy showed a significant reduction in acne lesions favoring PDT in most studies.

The second systematic review34 of 16 RCT and 3 controlled trials (CT) examined the efficacy of PDT (5 RCTs), infrared lasers (4 RCTs), broad-spectrum light sources (3 RCTs, 1CT), pulsed dye lasers (RCTs, 1CT), intense pulsed light (1 RCT, 2CT), and a potassium titanyl phosphate laser (1RCT) in the reduction of acne lesions. The authors conclude that the most dependable results from the above therapies are achieved with PDT through the reduction of inflammatory acne lesions. Limitations of this review include “suboptimal methodological quality” secondary to questionable randomization methods in 10 of the studies, but were included due to a limited selection. Several of the studies in this review are included in Table 6.

B: Photopneumatic therapy – Isolaz™

Search strategy: Keywords used include “acne and photopneumatic therapy”, “pneumatic energy”, “pneumatic therapy”, and “Isolaz”. There were no meta-analyses or systematic reviews at the time of search. Randomized controlled trials were limited to one unpublished study. No mention of randomization was found in the first two clinical trials listed below; these papers were obtained through inquiry to Solta Medical (Hayward, CA).

| Clinical Trials: | 2 |

| RCTs: | 1 |

Gold and Biron40 examined the efficacy of Isolaz™ (AestheraCorporation, Pleasanton, CA) a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) -approved treatment, in 11 mild to moderate acne patients with 4 total treatments at 3-week intervals. Three months after the fourth treatment, both inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions showed a statistically significant decrease (P = 0.0137, 0.0383, respectively) in number, but was based on 6 of the 11 patients.

Wanitphakdeedecha et al41 also examined photo-pneumatic therapy in the treatment of 18 patients with mild–severe acne vulgaris. Patients received 4 treatments at 2-week intervals. An improvement of acne was demonstrated after 2 treatments in most patients through clinical improvement scores and acne lesion counts. Severe acne patients received the greatest benefit in acne clearance from this treatment.

A recent unpublished study examining Isolaz + adapalene 0.3% versus adapalene 0.3% alone, showed a quicker improvement with the combination therapy, but after 4 weeks response to both treatments was similar.

C: Glycolic and salicylic acid chemical peels

Search strategy: Keywords used included “acne and chemical peels”. Papers were limited to meta-analyses, systematic reviews and RCTs in the English language. No meta-analysis or systematic review was found at the time of search. RCTs were extremely limited and were at least investigator-blind and randomized.

| RCTs: | 3 |

The RCT of Kessler et al42 examined the effectiveness of both a 30% glycolic acid peel and a 30% salicylic acid peel in 20 patients every 2 weeks for 6 treatments, with a split-face application. Both peels showed a statistically significant decrease in acne lesions (P < 0.05) by the second treatment session, and proved equally effective.

Ilknur et al43 also showed an equal effectiveness in the reduction of acne lesions with glycolic and amino fruit acid peels given every 2 weeks for 6 months in a split-face study with 24 patients. Noninflammatory lesions significantly decreased (P < 0.05) after 1 month with the glycolic acid peel and after 2 months with the amino fruit acid peel. Inflammatory lesions also decreased significantly (P < 0.05) after 5 and 6 months with the glycolic acid peel and after 5 months with the amino fruit acid peel.

In an unpublished study comparing 30% salicylic acid peels to Isolaz™, both treatments resulted in a similar improvement of acne lesions, with the Modified Global Acne Grading Scale demonstrating acne improvement before and after treatment of both procedures.

Conclusions

Blue and red light and PDT offer some relief in the reduction of inflammatory acne lesions, with the most promising results seen with PDT. The photosensitizers aminolevulinic acid and methyl aminolavulinate display similar effectiveness. Photopneumatic therapy (Isolaz™) and chemical peels also offer an improvement in acne lesions; however more studies are needed to fully assess the effectiveness of these medical treatments.

The practice

Cautions

- Women of child-bearing age and acne treatments:

- ○ All topical acne therapy should be stopped if pregnancy occurs.

- ○ Topical retinoids should not be prescribed to pregnant women, women wishing to become pregnant, or nursing patients.

- ○ Oral tetracycline should not be taken by pregnant or nursing women.

- ○ The only FDA-approved medication to treat acne during pregnancy is azelaic acid (category B) and should be used with caution in nursing women.

- ○ It is imperative for women who are starting oral isotretinoin (category X) to practice 2 forms of birth control, participate monthly in pregnancy tests, and not become pregnant for at least 1 month after cessation of therapy due to oral isotretinoin’s known teratagenic effects.

Management

Stress to patients that most acne therapies require at least 8 to 12 weeks to see improvement.

Start with a medication with the most tolerable side effects and increase in strength as needed and tolerated by the patient.

Clinicians should match the patient’s skin type to formulation vehicle (dry skin type creams; oily skin type solutions/gels/salicylic acid products; normal skin type lotions).

Assessment

Thorough examination of face, neck, chest, and back.

Obtain detailed history of past acne medications.

Question males about anabolic steroid use and females about irregular periods, facial hair, and loss of scalp hair.

Treatment

Table 7.

Global Acne Grading System44

| Location (L) | Clinical assessment (A) | Local score | Global score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forehead = 2 | 0 = no lesion | Local score = L × A | 0 = None |

| Right cheek = 2 | 1 = ≥ 1 comedo | sum of local scores = global score | 1–18 = mild acne |

| Left cheek = 2 | 2 = ≥ 1 papule | 19–30 = moderate acne | |

| Nose = 1 | 3 = ≥ 1 pustule | 31–38 = severe acne | |

| Chin = 1 | 4 = ≥ 1 nodule | >39 = very severe acne | |

| Chest/upper back = 3 |

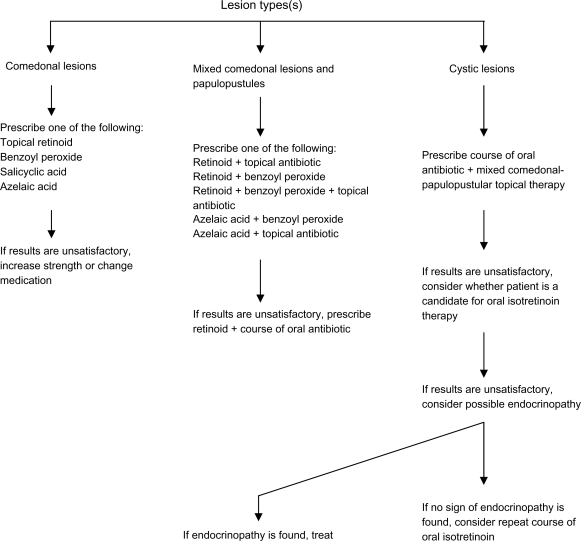

Figure 1.

Guideline for acne treatment based on lesion type.

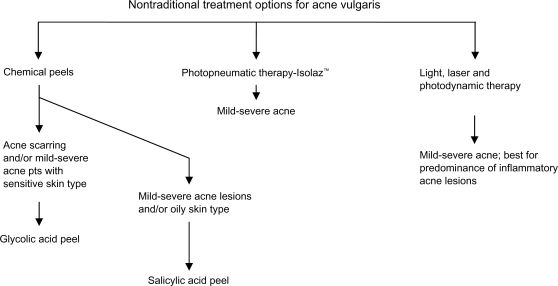

Figure 2.

Adjunctive acne treatment algorithm.

Specialist referral

Mild–severe acne patients.

Patient interest in nontraditional approaches to acne.

Table 2.

RCTs of topical antibiotic therapies

| Reference | No of patients/treatment duration | Acne severity | Treatment | Reduction of inflammatory lesions, % | P value | Reduction of noninflammatory lesions, % | P value | Total reduction of lesions, % | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cunliffe et al17 | CDP/BPO gel = 40 clindamycin gel = 39 for 16 weeks |

mild-moderate | CDP 1%/BPO gel 5% vs CDP 1% gel | 50b 30 |

0.035e | 45b 23 |

0.046e | 53 27.5 |

0.013e |

| Babayeva et al18 | SA + CDP = 23 all-TRA + CDP = 23 for 12 weeks |

mild-moderate | 3% SA/CDP 1% lotion vs all-TRA 0.05%/CDP 1% lotion | 78/4.9 ± 4.1c 81.5/3.8 ± 3.2 |

0.366d | 81.5/8.3 ± 4.7 87/5.8 ± 3.5 |

0.059d | 80/13.2 ± 6.9 86/9.6 ± 5.7 |

0.081d |

| Lookingbill et al19 | CDP/BPO gel = 95 CDP gel = 89 BPO gel = 92 vehicle gel = 58 for 11 weeks |

mild-moderatea | CDP 1%/BPO gel 5% (1) vs CDP 1% gel (2) vs BPO 5% gel (3) vs vehicle gel (4) | 61 35 39 5 |

(1, 2, 3) vs (4) ≤ 0.002 @ 2–11 weeks (1) vs (3) < 0.02 @ 2, 8, 11 weeks (1) vs (2) < 0.02 @ 2, 5, 8, 11 weeks (2) vs (3) = NS+ |

36 9 30 −11 |

(1) vs (4) ≤ 0.004 @ 2–11 weeks (3) vs (4) ≤ 0.005 @ 5–11 weeks (2) vs (4) = 0.04 @ 11 weeks (1, 3) vs (2) ≤ 0.01 (throughout study) (1) vs (3) = NS+ |

n/a | n/a |

| Webster et al20 | CDP 1.2%/BPO 2.5% gel-moderate = 643 CDP 1.2%/BPO 2.5% gel-severe = 154 CDP-moderate = 653 CDP-severe = 159 BPO-moderate = 667 BPO-severe = 142 placebo-moderate = 319 placebo-severe = 76 for 12 weeks |

moderate | CDP 1.2%/BPO 2.5% gel (1) vs CDP 1.2% (2) vs BPO 2.5% (3) vs placebo (4) | 68 56 58 36.4 |

(1) vs (4) < 0.001 (1) vs (2,3) < 0.001 |

50 41 44 25 |

(1) vs (2) = 0.001 (1) vs (3) = 0.001 (1) vs (4) < 0.001 |

54 45 47 30 |

(1) vs (2) < 0.001 (1) vs (3) < 0.001 (1) vs (4) < 0.001 |

| severe | CDP 1.2%/BPO 2.5% gel (1) vs CDP 1.2% (2) vs BPO 2.5% (3) vs placebo (4) |

49 n/a n/a 24 |

(1) vs (4) < 0.001 | 45 n/a n/a 27 |

(1) vs (4) < 0.001 | 44 n/a n/a 19 |

(1) vs (4) < 0.001 |

Notes:

severity estimated from lesion counts;

data estimated from graph;

mean ± SD lesion count;

P value reflects mean ± SD lesion count;

between-group comparisons.

Abbreviations: all-TRA, tretinoin; CDP, clindamycin phosphate; NS, not significant; n/a, data not available; SA, salicylic acid.

Footnotes

Date of preparation: 30th November 2010

Conflicts of interest: None declared

Further reading

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, et al. Dermatology. London, Edinburgh, NY, Philadelphia, St Louis, Sydney, Toronto: Mosby; 2003. pp. 531–45. Section 6. [Google Scholar]

- Plewig G, Kligman AM. Acne and Rosacea. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

References

- 1.Zaenglein AL, Graber EM, Thiboutot DM, Strauss JS. Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest B, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, editors. Chapter 78. Acne vulgaris and acneiform eruptions. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7e: http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=2963025. Accessed August 8, 2010.

- 2.Dreno B, Poli F. Epidemiology of Acne. Dermatology. 2003;206(1):7–10. doi: 10.1159/000067817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zouboulis C, Piquero-Martin J. Update Future of Systemic Acne Treatment. Dermatology. 2003;206(1):37–53. doi: 10.1159/000067821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goulden V, Stables GI, Cunliffe WJ. Prevalence of facial acne in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(4):577–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gollnick H, Cunliffe W, Berson D, et al. Management of acne: a report from a global alliance to improve outcomes in acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(1 Suppl):S1–S37. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Health-care Research and Quality, Management of acne . Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Mar, 2001. Summary-Evidence Report/Technology Assessment: Number 17. AHRQ Publication No. 01-E018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Purdy S, DeBerker D. Acne vulgaris. Clin Evid. 2008;5:1714. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seidler E, Kimball A. Meta-analysis comparing efficacy of benzoyl peroxide, clindamycin, benzoyl peroxide with salicylic acid, and combination benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin in acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63(1):52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thiboutot D, Pariser D, Egan N, et al. Adapalene gel 0.3% for the treatment of acne vulgaris: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, controlled, phase III trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2):242–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.10.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan J, Gollnick H, Loesche C, et al. Synergistic efficacy of adapalene 0.1%-benzoyl peroxide 2.5% in the treatment of 3855 acne vulgaris patients. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010 Jul 28; doi: 10.3109/09546631003681094. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shalita A, Weiss JS, Chalker DK, et al. A comparison of the efficacy and safety of adapalene gel 0.1% and tretinoin gel 0.025% in the treatment of acne vulgaris: A multicenter trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34(3):482–485. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90443-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cunliffe WJ, Poncet M, Loesche C, Verschoore M. A comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of adapalene 0.1% gel versus tretinoin 0.025% gel in patients with acne vulgaris: a meta-analysis of five randomized trials. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139(Suppl. 52):48–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.1390s2048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shalita A, Berson D, Thiboutot D, et al. Effects of tazarotene 0.1% cream in the treatment of facial acne vulgaris: pooled results from two multicenter, double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled, parallel-group trials. Clin Ther. 2004;26(11):1865–1873. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shalita A, Miller B, Menter A, et al. Tazarotene cream versus adapalene cream in the treatment of facial acne vulgaris: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2005;4(2):153–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thiboutot D, Arsonnaud S, Soto P. Efficacy and tolerability of adapalene 0.3% gel compared to tazarotene 0.1% gel in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7(6 Suppl):s3–s10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanghetti E, Dhawan S, Green L, et al. Randomized comparison of the safety and efficacy of tazarotene 0.1% cream and adapalene 0.3% gel in the treatment of patients with at least moderate facial acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9(5):549–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunliffe W, Holland K, Bojar R, Levy S. A randomized, double-blind comparison of a clindamycin phosphate/benzoyl peroxide gel formulation and a matching clindamycin gel with respect to microbiologic activity and clinical efficacy in the topical treatment of acne vulgaris. Clin Ther. 2002;24(7):117–1133. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(02)80023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Babayeva L, Akarsu S, Fetil E, Gunes AT. Comparison of tretinoin 0.05% cream and 3% alcohol-based salicylic acid preparation in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010. Jul 28, [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Lookingbill DP, Chalker DK, Lindholm JS, et al. Treatment of acne with a combination clindamycin/benzoyl peroxide gel compared with clindamycin gel, benzoyl peroxide gel and vehicle gel: combined results of two double-blind investigations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(4):590–595. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Webster G, Rich P, Gold M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of a fixed combination of clindamycin phosphate (1.2%) and low concentration benzoyl peroxide (2.5%) aqueous gel in moderate or severe acne sub-populations. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8(8):736–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ozolins M, Eady E, Avery A, et al. Comparison of five antimicrobial regimens for treatment of mild to moderate inflammatory facial acne vulgaris in the community: randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9452):2188–2195. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17591-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peck G, Olsen T, Butkus D, et al. Isotretinoin versus placebo in the treatment of cystic acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;6(4 Pt 2 Suppl):735–745. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(82)70063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strauss J, Leyden J, Lucky A, et al. A randomized trial of the efficacy of a new micronized formulation versus a standard formulation of isotretinoin in patients with severe recalcitrant nodular acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45(2):187–195. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.115965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown J, Farquhar C, Lee O, et al. Spironolactone versus placebo or in combination with steroids for hirsutism and/or acne (Review) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(4):CD000194. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muhlemann MF, Carter GD, Cream JJ, Wise P. Oral spironolactone: an effective treatment for acne vulgaris in women. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115(2):227–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1986.tb05722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne (Review) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD004425. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004425.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maloney J, Dietz P, Watson D, et al. Treatment of Acne Using a 3-Milligram Drospirenone/20-Microgram Ethinyl Estradiol Oral Contraceptive Administered in a 24/4 Regimen. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(4):773–781. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318187e1c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thiboutot D, Archer D, Lemay A, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a low-dose contraceptive containing 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol and 100 μg of levonorgestrel for acne treatment. Fertil Steril. 2001;76(3):461–468. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)01938-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plewig G, Cunliffe W, Binder N, Hoschen K. Efficacy of an oral contraceptive containing EE 0.03 mg and CMA 2 mg (Belara®) in moderate acne resolution: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase III trial. Contraception. 2009;80(1):25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leyden J, Shalita A, Hordinsky M, et al. Efficacy of a low-dose oral contraceptive containing 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol and 100 μg of levonorgestrel for the treatment of moderate acne: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(3):399–409. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.122192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lucky A, Henderson T, Olson W, et al. Effectiveness of norgestimate and ethinyl estradiol in treating moderate acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(5 Pt 1):746–754. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palombo-Kinne E, Schellschmidt I, Schumacher U, Graser T. Efficacy of a combined oral contraceptive containing 0.030 mg ethinylestradiol/2 mg dienogest for the treatment of papulopustular acne in comparison with placebo and 0.035 mg ethinylestradiol/2 mg cyproterone acetate. Contraception. 2009;79(4):282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamilton FL, Car J, Lyons C, et al. Laser and other light therapies for the treatment of acne vulgaris: systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160(6):1273–1285. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haedersal H, Togsverd-Bo K, Wulf HC. Evidence-based review of lasers, light sources and photodynamic therapy in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(3):267–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barolet D, Boucher A. Radiant near infrared light emitting diode exposure as skin preparation to enhance photodynamic therapy inflammatory type acne treatment outcome. Lasers Surg Med. 2010;42(2):171–178. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiegell SR, Wulf HC. Photodynamic therapy of acne vulgaris using 5-aminolevulinic acid versus methyl aminolevvulinate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(2 Suppl):S60–S62. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiegell SR, Wulf HC. Photodynamic therapy of acne vulgaris using methyl-aminolaevulinate: a blinded, randomized, controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154(5):969–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.07107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horfelt C, Frohm-Nilsson M, Wiegleb Edstrom D, Wennberg AM. Topical methyl aminolaevulinate photodynamic therapy for treatment of facial acne vulgaris: results of a randomized, controlled study. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(3):608–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orringer JS, Sachs D, Bailey E, et al. Photodynamic therapy for acne vulgaris: a randomized, controlled, split-face clinical trial of topical aminolevulinic acid and pulsed dye laser therapy. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2010;9(1):28–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2010.00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gold MH, Biron J. Efficacy of a novel combination of pneumatic energy and broadband light for the treatment of acne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7(7):639–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wanitphakdeedecha R, Tanzi EL, Alster TS. Photopneumatic therapy for the treatment of acne. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8(3):239–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kessler E, Flanagan K, Chia C, et al. Comparison of α and β-Hydroxy acid chemical peels in the treatment of mild to moderately severe facial acne vulgaris. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34(1):45–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ilknur T, Demirtasoglu M, Unlu M, et al. Glycolic acid peels versus amino fruit acid peels for acne. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2010;12(5):242–245. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2010.514919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doshi A, Zaheer A, Stiller M. A comparison of current acne grading systems and proposal of a novel system. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36(6):416–418. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1997.00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]