Abstract

Past research has established that delayed first language exposure is associated with comprehension difficulties in non-native signers of American Sign Language (ASL) relative to native signers. The goal of the current study was to investigate potential explanations of this disparity: do non-native signers have difficulty with all aspects of comprehension, or are their comprehension difficulties restricted to some aspects of processing? We compared the performance of deaf non-native, hearing L2, and deaf native signers on a handshape and location monitoring and a sign recognition task. The results indicate that deaf non-native signers are as rapid and accurate on the monitoring task as native signers, with differences in the pattern of relative performance across handshape and location parameters. By contrast, non-native signers differ significantly from native signers during sign recognition. Hearing L2 signers, who performed almost as well as the two groups of deaf signers on the monitoring task, resembled the deaf native signers more than the deaf non-native signers on the sign recognition task. The combined results indicate that delayed exposure to a signed language leads to an overreliance on handshape during sign recognition.

Keywords: ASL, Sign language, Perception, Sign recognition, Lexical access, Language experience, Delayed first language acquisition, Second language acquisition

Introduction

The aim of this study is to investigate the effects of early language learning experience on language processing in American Sign Language (ASL). ASL is the primary language used in the Deafi communities of the United States and parts of Canada. It has a lexicon and grammar that are distinct from the spoken languages in use in the same communities (e.g., English). ASL is also distinct from other signed languages (e.g., British Sign Language). Studies of language processing in English and other spoken languages have primarily been concerned with monolingual native speakers. An important contrast between speaking and signing communities is the relative frequency of native to non-native language users. In many spoken language communities, native speakers are common. By contrast, most individuals who use a signed language as their primary language did not acquire the signed language from birth, and would be considered “non-native” signers by standard psycholinguistic definitions.ii Of the few studies on signed language processing, most have focused on native signers. Thus, the larger and more “typical” population of non-native signers is poorly understood. The current study compares language processing in three groups of signers with the goal of shedding more light on the consequences of delaying language exposure past infancy. The three groups include:

-

1)

deaf non-native signers who were exposed to ASL between the ages of 10 and 18, and who use ASL as their primary language;

-

2)

hearing second language (L2) signers who acquired English as their native language and subsequently learned ASL as a second language between the ages of 16 and 26, and who use ASL regularly, but not as their primary language;

-

3)

a control group of deaf native signers who were exposed to ASL by family members in early infancy, and who use ASL as their primary language.

There is now considerable evidence that deaf adults who acquired ASL in infancy outperform deaf adults who acquired ASL as a first language in childhood or adolescence on a wide variety of language tasks (Emmorey, Bellugi, Frederici, & Horn, 1995; Mayberry & Fischer, 1989; Newport, 1990). Mayberry and colleagues have documented important differences in comprehension between deaf native and non-native signers through sentence shadowing and recall tasks (Mayberry, 1993; Mayberry & Eichen, 1991; Mayberry & Fischer, 1989) and grammaticality judgment tasks (Boudreault & Mayberry, 2006). Deaf non-native signers in these studies recall fewer signs, delete bound morphemes, and make qualitatively different errors than native signers. Specifically, non-native signers have a tendency to replace target signs with phonologically related substitutes that are semantically anomalous in the sentence context. Further, longitudinal studies of non-native signers first exposed to ASL in adolescence demonstrate that despite rapid gains in both lexical and grammatical expression, deficits in comprehension abilities persist (Morford, 2003).

Mayberry (1993) tested a third population of deaf signers that are not included in the current study. Called “late-deafened adults”, these signers learned English from birth, but became deaf in adolescence, and subsequently learned ASL as a second language at similar ages and with comparable years of experience to the deaf non-native first language learners. Interestingly, these individuals are much less likely to generate the types of errors produced by the deaf non-native first language learners of ASL, indicating that exposure from infancy to another language is a mitigating factor in comprehension of later learned languages (Mayberry, 1993). Mayberry & Lock (2003) provide additional evidence that severe language comprehension difficulties are specific to delayed first language (L1) acquisition and are not found in second language (L2) learners, regardless of the modality of the first language, signed or spoken. Specifically, both deaf native signers and hearing L2 learners of English demonstrate near-native performance on L2 English grammaticality judgment and sentence to picture matching tasks. Deaf non-native signers of ASL who have also learned English as a second language, by contrast, are slower and less accurate on these same tasks than the groups who had access to a first language in infancy. In sum, deaf non-native signers who did not have full access to a language in infancy and early childhood demonstrate deficits in comprehension on both L1 and L2 comprehension tasks, and relative to both native and L2 learners of those languages.

In this paper, we refer to deaf individuals who did not obtain communicative competence in a signed or spoken language in early childhood as non-native signers. Non-native signers are a very heterogenous group, and as we have pointed out, they make up the vast majority of deaf signers. Our study, however, does not evaluate the performance of this large and heterogeneous population. We specifically recruited deaf individuals that had unusually long delays in their initial exposure to ASL, on the order of 12 years on average. Prior to this age, these individuals also had very heterogeneous experiences in the amount of spoken and gestural communication in their families and schools, and in their degree of success in using these communicative methods. However, all of these participants consider ASL to be the first language that they were fully able to use in a competent manner. The hearing signers are also non-native signers, but are qualitatively different in their acquisition history since they had full competence in English prior to learning ASL. We refer to this group as hearing L2 signers.

Current research on deaf non-native signers is attempting to identify the locus of language processing breakdowns. Comprehension encompasses many sub-processes, each of which may be impacted differently by acquisition history (Clahsen & Felser, 2006; Scherag Demuth, Rösler, Neville, & Röder, 2004; Sebastián-Gallés, Echeverria, & Bosch, 1995). Mayberry (1994) summarizes much of the early work on non-native language processing in deaf signers and concludes that different types of errors in comprehension may be the result of a single underlying problem that has cascading effects on subsequent processing (cf. Mayberry & Eichen, 1991). More specifically, she hypothesizes that individuals who do not learn a first language in early childhood may have “controlled phonological processing, that is, nonautomatic and effortful phonological processing” (84), resulting in delays to lexical access and meaning integration. There are several possible ways that this hypothesis might be instantiated. For example, non-native signers could experience difficulty in the perception of phonological parametersiii, which in turn, would delay the onset of sign recognition processing, whether or not non-native signers had actual difficulties recognizing signs on the basis of the phonological representation. Alternatively, non-native signers might be able to perceive sign parameters efficiently, but have difficulty relating the phonological form to lexical representations. Finally, both problems could disrupt language processing in non-native signers, compounding the difficulties at each stage of processing.

To date, there are no studies of sign perception and sign recognition with the same set of participants, allowing for a direct comparison of processing across these two domains. While it is likely that both sign perception and sign recognition will show an influence of delayed exposure to language, a comparison of performance across these domains can be instructive to our growing understanding of the effects of early language experience on language acquisition outcomes. Further, a comparison to second language learners of ASL can distinguish effects common to both L1 and L2 learners who began acquisition later than early infancy, from those effects that are specific to individuals with restricted early language experience. We investigate these issues by evaluating the performance of native, non-native and L2 signers on a monitoring task (Foss & Swinney, 1973), and a gating task (cf. Pollack & Pickett, 1963 for English; cf. Clark & Grosjean, 1982; Grosjean, 1981; Emmorey & Corina, 1990 for ASL).

Study 1: Handshape and Location Monitoring

The first task is modeled after spoken language phoneme monitoring, and requires participants to attend to a list of stimuli, in this case ASL signs, and to respond whenever a target sub-lexical unit, in this case a handshape or a location, is detected. Monitoring experiments with spoken language stimuli have generally found that participants are faster to detect full words and syllables relative to phonemes (Foss & Swinney, 1973). Results have demonstrated differential sensitivity to the particular perceptual units present in the native language. Native speakers of English, for example, are slower than native speakers of Japanese to detect mora, a phonological unit present in Japanese but absent in English (Cutler & Otake, 1994). For the present study, we hypothesized that non-native and L2 signers of ASL would be slower and less accurate than native signers to detect both handshape and location units. In order to be certain that all participants could nevertheless successfully complete the task, participants were shown a sign that included the targeted handshape or location. This sign was then included in the list of stimuli that participants viewed when performing the monitoring task, and is referred to as the familiar condition. If participants had difficulty identifying the target in novel signs, i.e., signs they had not previously viewed during the experiment, they would minimally be able to respond to the presentation of the target in the familiar sign. In sum, three independent variables were manipulated in the monitoring experiment: language background (deaf non-native, hearing L2 or deaf native signers), sign familiarity (familiar, novel), and phonological parameter (handshape, location).

Method

Participants

Thirty-six individuals participated in the study. Participants were informed of the nature of the experiment in ASL and English, and all 36 individuals gave their consent to participate. All participants were paid $25 for their participation.

Participants were recruited into three groups. The deaf non-native signer group (5 women, 7 men) were all born deaf to hearing parents and began acquiring ASL between the ages of 10 and 18 (M=12.67). They had an average of 30 years of experience signing ASL (range 16 – 44), and an average of 15 years of education (some vocational or undergraduate training beyond high school). Ten of 12 participants were educated at least in part in schools that focused on oral training; half of those participants were also mainstreamed with hearing students, while the other half were in classrooms for deaf students. The two participants who did not attend oral schools were both mainstreamed, but also had some experience in a self-contained classroom in which the teachers used a total communication approach. Participants in the hearing L2 signer group (7 women, 4 men, 1 unreported) were all hearing and had acquired ASL as a second language between the ages of 16 and 26 (M=21.83). They had an average of 21 years experience signing ASL (range 14 – 25), and 17 years of education (post-graduate study). The native signer group (6 women, 6 men) were all born deaf. Eleven had at least one deaf parent and one had an older deaf sibling; all acquired ASL in the home prior to attending school. They had an average of 31 years of experience signing ASL (range 22 – 42 years), and 16 years of education (undergraduate degree). No significant difference was found in the length of experience signing ASL between the two groups of deaf signers (t (22) = .75, n.s.). The hearing L2 signers differed from the other two groups both in their age of acquisition and their years of experience using ASL. All participants were highly practiced signers of ASL and reported using it on a daily basis, either as their primary language of communication in the case of the deaf signers, or in maintaining daily social or professional relationships in the case of the hearing signers.

Materials

Nine handshapes and six locations were selected as targets for a total of 15 experimental blocks. Additionally, two handshapes and one location were selected as targets for three practice blocks. For each block, five signs were selected that included the target, and five distracter signs were selected that did not include the target. One target sign and one distracter sign were then assigned to the familiar condition. These signs were presented four times during the appropriate experimental block. The remaining 8 signs (4 target, 4 distracter) were each presented once in the novel condition, for a total of 16 stimuli in each block: 8 stimuli that included the target (4 familiar, 4 novel), and 8 distracters (4 familiar, 4 novel).

Stimuli were generated by filming a native signer of ASL producing each sign in citation form. Familiar signs were filmed multiple times, and four tokens of the familiar signs were selected for use in the experiment rather than repeatedly using the same recording. Each stimulus consisted of 1000 ms of a still frame of the signer, followed by the citation form of the sign. On average, the target sub-lexical unit occurred 429 ms after sign onset. Videos were compressed and presented as QuickTime movies at 720 × 480 pixels, and 30 frames per second.

Targets were presented to participants in the form of jpeg images showing the target handshape or, in the case of location targets, as an image of a signer's face or body with a pink square highlighting the target location.

Procedure

All contact with participants was carried out by a deaf research assistant fluent in ASL. The researcher met the participant at a location of the participant's choice. Participants were informed of the nature of the task, risks, benefits and conditions of participation through a written form in English, with additional explanation provided by the research assistant in ASL. Those who agreed to participate and signed the consent form were then asked to fill out a language survey describing their acquisition history with respect to ASL. For the experimental task, participants were seated in front of a Macintosh PowerBook G3 Laptop using PowerLaboratory software (Chute, 1996). Participants were given 3 practice blocks, during which they were able to ask the experimenter any remaining questions. There were 15 experimental blocks.

Each experimental block began with the presentation of the target handshape or location and a prompt to press the spacebar to see an example sign with that handshape or location. After the spacebar was pressed, participants saw the example sign, which was also the target sign for the familiar condition. Participants were prompted to press the spacebar to begin the block, following which the 16 signs (4 familiar targets, 4 familiar distracters, 4 novel targets, 4 novel distracters) for that block were presented in random order. Participants were instructed to press a green key on the keyboard with their dominant index finger as quickly and as accurately as possible whenever they saw the target handshape or location. No response was required to signs that did not have the target sub-lexical unit. No feedback was given regarding the accuracy of the response. At the end of each block, participants were prompted to press the space bar to begin the next block when they were ready. The entire procedure was completed in approximately 20 minutes.

Results

The effects of language background (deaf native, deaf non-native and hearing L2), sign familiarity (familiar, novel), and phonological parameter (handshape, location) on reaction time for correct responses were evaluated with a 3 × 2 × 2 repeated measures mixed three-way ANOVA. There was a main effect of sign familiarity, F1(1, 33) = 128.80, p < .001, F2(1,116)=47.87, p < .001, on reaction time. Participants responded to the target sub-lexical unit in the sign that was presented as the “example” sign on average 155 ms faster than in the signs that had not previously been seen. There was also a significant interaction of phonological parameter and language background, F1(2, 33) = 3.81, p < .05, F2(2,232) = 23.29, p < .001. The three groups of participants differed with respect to their relative performance on the handshape vs. the location trials. Fisher's LSD with adjustments for multiple comparisons indicated that the deaf non-native signers were significantly faster on the handshape than on the location trials (p < .05 in the subject analysis, p < .01 in the item analysis), whereas the other two groups did not show this pattern. The deaf native signers were faster on location than on handshape trials, although this difference while significant in the item analysis (p < .01) only approached significance in the subject analysis (p = .076). The hearing L2 signers, who were somewhat slower than the other two groups, had similar monitoring times for handshape and location targets (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Handshape and Location monitoring RTs by group

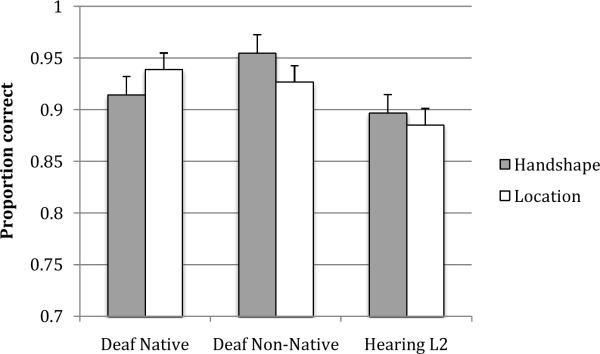

A second ANOVA evaluated effects of language background, sign familiarity and phonological parameter on monitoring accuracy. Because accuracy was at ceiling in the familiar condition, all accuracy scores were normalized using an arcsine transformation. Again there was a main effect of sign familiarity on accuracy, F1(1,33) = 153.86, p < .001, F2(1,116) = 38.15, p < .001. Accuracy was higher in the familiar condition (98.4%) than in the novel condition (92%). There was a main effect of language background on monitoring accuracy, F1(2, 33) = 3.54, p < .05, F2(2,232) = 7.61, p < .001. Pairwise comparisons using Fischer's LSD revealed that the deaf non-native group was significantly more accurate than the hearing L2 group (p < .05 Subjects, p < .01 Items), and there was a trend for the deaf non-native group to be more accurate than the native group (p = .07 Subjects, p < .05 Items). A significant interaction of familiarity and language background emerged in the item analysis, F2(2,232) = 10.32, p < .001, but not the subject analysis, F1(2, 33) = 4.98, p = .13, due to the fact that effects of language background were more pronounced in the novel condition, when participants were responding to signs that had not previously been viewed. Pairwise comparisons indicated that the deaf non-native signers (p < .001 Subjects, p < .001 Items) and the deaf native signers (p < .01 Subjects, p < .001 Items) were more accurate than the hearing L2 signers in the novel condition (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Handshape and Location monitoring accuracy by group in the Novel condition

Discussion

Contrary to our hypothesis, the deaf non-native signers were not slower or less accurate in the detection of the handshape and location primes relative to the native signers. Indeed, their performance overall was the best of the three groups. The only significant difference in RT performance was a within-group difference for the deaf non-native signers who were faster on handshape than on location monitoring trials, as well as a trend for the native signers to respond more rapidly on location than on handshape monitoring trials. The primary differences across groups were found in the accuracy levels. Interestingly, the deaf non-native signers were the most accurate, differing significantly from both native and L2 signers, particularly in the novel condition. The native signers were also more accurate than the hearing L2 signers, but only in the novel condition.

These results allow us to rule out at least one explanation of comprehension difficulties in non-native signers. The superior monitoring performance of this group would be inconsistent with an explanation that poor comprehension is a result of inadequate abilities to perceive handshape and location parameters. There may nevertheless be perceptual processing differences in native and non-native signers (cf. Best, Mathur, Miranda, & Lillo-Martin, 2010; Morford, Grieve-Smith, MacFarlane, Staley & Waters, 2008). Hildebrandt & Corina (2002) report a study in which both native and non-native signers of ASL were asked to observe a phonologically permissible nonce sign, and to select the most “similar” sign from a set of three nonce signs that shared handshape, location or movement with the target sign. Native signers showed a preference for nonce signs sharing the movement parameter, while non-native signers overwhelmingly selected signs overlapping in handshape. It is possible that both our monitoring task and Hildebrandt & Corina's sign similarity judgement task tap metalinguistic or post-perceptual rather than perceptual processing. However, as more and more studies are finding differences in how non-native signers respond to the handshape parameter in experimental settings, it is important to consider how a heightened sensitivity to this aspect of the sub-lexical structure of signs may impact comprehension processes more generally. We return to this point in the general discussion.

We suspect that the superior accuracy of the deaf non-native signers may be an indication that they completed this task pre-lexically, while the other groups, or at least the native signers, could not inhibit lexical access of the stimuli prior to making a monitoring response. This is a second reason to interpret the results of the experiment with caution. Additional monitoring studies using nonce signs would be sufficient to evaluate this possibility.

We turn now to the second study that investigated sign recognition skills in the same set of participants, to evaluate whether language experience in early development affects lexical processing.

Study 2: Gating

The gating task (Pollack & Pickett, 1963) is ideal for investigating the earliest stages of lexical processing. In particular, the task evaluates the amount of phonetic information required to identify words or signs. We hypothesized that both non-native and L2 signers would not be able to identify ASL signs as rapidly as native signers, and specifically, that they would consider a broader range of lexical competitors prior to selecting the appropriate lexical target.

The stimuli for this gating task consisted of repeated video presentations of a target sign. The first presentation, or gate, consisted only of the sign onset. Subsequent trials presented increasingly longer segments of the sign, with each stimulus beginning at sign onset. The final trial for a specific target included the full sign. After each trial, participants attempted to identify the target sign.

Method

Participants

The same participants who completed Experiment 1 also completed Experiment 2.

Materials

Thirty-five ASL signs were selected from vocabulary included in lessons in published ASL curricula (see Appendix 1). Each sign was videotaped in the carrier sentence SHOW-ME SIGN <target sign> (Show me the sign <target sign>) by a native signer. The target sign was cut from the carrier sentence at the transition from the sign SIGN to the target sign. This transitional point was determined by selecting the frame in which the dominant signing hand moved out of the trajectory of the preceding sign and began the movement trajectory of the target sign. Six gates were prepared for each stimulus. The first gate consisted of the first 4 frames of the sign (132 ms). The second through fifth gates were increased by 2 frames (66 ms) each (6, 8, 10 and 12 frames). The sixth and final gate was 30 frames (1 second) in duration, and presented the full target sign. A one second animation was added to the onset of each stimulus to allow participants to focus their attention on the location of the stimulus on the computer screen. Participants saw a circle closing to a point in the middle of the video frame. When the circle was completely closed, the stimulus began. Videos were compressed and presented as QuickTime movies at 720 × 480 pixels, and 30 frames per second.

Procedure

Following completion of Experiment 1, the consenting procedure was repeated for Experiment 2. Those who agreed to participate and signed the consent form were then presented with the second experiment. Participants were told they would see only part of a sign, and were asked to guess what sign was presented. Participants were encouraged to provide a response even when they had no idea what the sign was. Participants were given 5 practice trials, during which they were able to ask the experimenter any remaining questions. After any questions were resolved, the experiment began. There were 30 experimental trials.

Each experimental trial began with the presentation of a fixation point and a prompt to press the spacebar to begin the trial. Immediately after the spacebar was pressed, the first gate of the first stimulus was presented. Participants saw the 1 second animation followed by the 4 frames of the first sign. A question mark appeared centered over the location of the stimulus and served as a visual mask as well as a prompt for participants to sign a response. Participants were instructed to guess the identity of the sign, even if they were uncertain, and then to press the spacebar to proceed to the next gate. Participants saw all 6 gates of a target sign before moving to the next trial. Two button presses were required to move to a new trial, so that participants were always warned that they would be seeing a novel stimulus. The stimuli were presented in a fixed random order. Responses were videotaped. The entire procedure was completed in approximately 25 minutes.

Signed responses were transcribed from the videos and evaluated for phonological overlap with the target sign by two deaf research assistants fluent in ASL. Inter-rater reliability was evaluated for approximately 10% of the data. Cohen's Kappas were calculated for agreement on the identity of the signs (K = .96, p < .05, s.e. = .010) and agreement on whether the signed responses overlapped with the target signs in location (K = .73, p < .05, s.e. = .032), handshape (K = .82, p < .05, s.e. = .028) and movement (K = .93, p < .05, s.e. = .017).

Results

On average, participants were able to correctly identify the target signs after the second gate, or just 6 frames (198 ms). There was a significant effect of language background on the number of gates needed to identify a sign as revealed by a one-way ANOVA, F1(2, 33) = 4.62, p<.02, F2 (2,87) = 2.62, p=.078. Native signers identified the signs after just 1.9 gates (188 ms) on average, whereas both the deaf non-native and the hearing L2 signers identified the signs after 2.3 gates (218 ms) on average.

Two additional measures of the ease with which participants were able to recognize the target sign were computed. First, we calculated the number of gestured, non-ASL responses on the first gate as a measure of the frequency with which participants were unable to identify any potential ASL signs on the basis of the phonetic input. All signed responses that could not be identified as an ASL sign by the first coder were reviewed by a second coder. Only signs that both coders identified as gestures were included in this analysis. A one-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of language background on the number of gestured responses, F1(2,33) = 3.21, p = .053, F2 (2,87) = 15.43, p < .001, see Table 2. Gestured responses were much more frequent for the deaf non-native signers and the hearing L2 signers than among the native signers. The frequency of gestured responses varied by participant, but whereas only 3 of the native participants produced a gestured response, 8 of the 12 hearing L2 learners produced a gestured response, and all but one of the deaf non-native signers produced a gestured response. A correlation analysis of gestured responses and number of gates required to identify the target sign indicated a strong relationship between these two measures, r = .60. We also tabulated the number of unique responses across the entire group (correct and incorrect) to the first gate, and averaged this value across trials. This analysis revealed that the native signers' responses were more consistent with each other (2.2 signs per trial) than the deaf non-native (3.6 signs) or the hearing L2 (4.0 signs) signers.

Table 2.

Mean number and range of gates and of gestured responses by group

| Number of Gates | Number of Gestured Responses | |

|---|---|---|

| Deaf native signers (n=12) | 1.9 [1.5, 2.4] | .5 [0, 3] |

| Deaf non-native signers (n=12) | 2.3 [1.9, 2.8] | 3.6 [0, 15] |

| Hearing L2 signers (n=12) | 2.3 [1.7, 3.1] | 2.1 [0, 8] |

All prior gating studies of ASL found that location and orientation were identified earliest during sign recognition, followed by handshape (Clark & Grosjean, 1982, Emmorey & Corina, 1990, Grosjean, 1981). We investigated which phonological parameter was identified first in the current study by evaluating the proportion of non-target sign responses that shared the same location, handshape or movement with the target sign. A two-way repeated measures ANOVA with language background as a between-subjects variable and phonological parameter as a within-subjects variable revealed a significant main effect of language background on the proportion of non-target signs with the same location, handshape or movement as the target sign, F(2,33) = 19.27, p < .001. Pairwise comparisons revealed that native signers more frequently responded with signs that were phonologically similar to the target signs than the deaf non-native (p < .001) and hearing L2 (p < .02) signers (see Figure 3). Moreover, the hearing L2 signers more often responded with non-target signs that were phonologically similar to the target signs than the deaf non-native signers (p < .01).

Figure 3.

Proportion of non-target responses sharing handshape, location, or movement with the target sign

There was also a main effect of phonological parameter, F(2,66) = 109.66, p < .001. Participants were most likely to respond with a sign that matched the target in handshape (63%), followed by location (45%). Consistent with past studies, very few responses prior to sign recognition included the target movement (20%). Finally, there was a significant interaction of language background and phonological parameter (F(4,66) = 3.62, p < .01). Pairwise comparisons indicated that both deaf non-native (p < .001) and hearing L2 (p < .01) signers were more likely to produce responses with the correct handshape than the correct location, but this was not the case for native signers, who identified both parameters correctly in the majority of their responses. All groups were more likely to produce a response with the correct handshape and location than the correct movement, as has been documented in prior studies (all ps < .001 except for deaf non-natives, location vs. movement, p < .01). Further, comparisons across groups revealed that the native signers' responses matched the target sign in both location and movement more often than responses of the deaf non-native and hearing L2 signers (all ps < .05), and their responses were more likely to match the target sign in handshape than the deaf non-native signers (p < .05) as well. The hearing L2 signers' responses were also more likely to match the target sign in location (p < .001) and movement (p < .05) than the deaf non-native signers' responses.

Discussion

The results of the gating task demonstrate clear differences in lexical access across the three participant groups. Language experience influences both the speed and the manner of sign identification processes. The most straightforward difference is in the amount of the sign signal necessary for sign recognition. Non-native signers needed to see about 1 video frame more than native signers to recognize the sign stimuli in the current study. This finding replicates the results of Emmorey & Corina's (1990) gating study that also compared native and non-native signers. In addition to replicating non-native signers' reliance on a longer sign onset for recognition, we found three important differences in the process of sign identification that have not been documented in prior gating studies.

The first of these differences concerns the phonological relationship between responses and the target sign. Native signers' responses were closely related phonologically to the target sign, as well as to each other's responses. Non-native signers' responses, by contrast, shared fewer phonological parameters with the target signs, and were also less similar to responses from other non-native signers. Assuming an interactive model of word recognition (e.g., Marslen-Wilson, 1987, Dijkstra & Van Heuven, 2002), this pattern in the results is a possible indication that the spread of activation across the lexicon is more variable in non-native than native signers, or alternatively, that there is greater individual variability in lexical representations among non-native than among native signers.

A second difference is that the phonological parameters that were shared by responses and the target sign differed across groups. The native signers' responses indicate that they initially identify both the handshape and the location of the target sign, and subsequently identify the movement. The hearing L2 signers first identified the target handshape, followed by location, and finally by movement. The deaf non-native signers produced responses that were the least likely to overlap in any of the three parameters, but handshape was clearly the primary basis for their responses. Fewer than 25% of their non-target responses shared location, and fewer than 10% of their non-target responses shared movement with the target sign. Thus, while native signers anticipate the movement parameter on the basis of location and handshape cues in the input, the non-native signers show little evidence of integrating phonological cues, relying instead on handshape alone to guide their lexical search.

These differences indicate that the structure of the lexicon may well differ between these groups. The results also parallel the findings of Study 1, which showed an enhanced sensitivity to handshape by deaf non-native signers, but in a task that did not require sign recognition. Native signers, by contrast, showed a trend for greater sensitivity to location in Study 1, and were also significantly more likely to identify signs on the basis of location in this task. Further study is needed to determine whether an overreliance on handshape is disruptive to lexical access for non-native signers, and whether sensitivity to location and movement can be trained in members of this population in such a way that it improves lexical processing (cf. Fukkink, Hulstijn & Simis, 2005 for evidence of increased efficiency in lexical processing for spoken language L2 learners through training). One way that reliance on handshape to identify signs could be detrimental to non-native signers is that handshape alone is a poorer constraint on lexical competitors than the combination of multiple parameters, such as location and handshape (cf. Emmorey & Corina, 1990). A signer searching the lexicon for all signs that include an extended |index| finger as the dominant handshape, for example, will have to consider and reject hundreds of signs, whereas the same handshape combined with the location of the |cheek| limits the possible signs to only a handful.

A third and final noted difference between non-native and native signers concerns the production of gestured responses. The non-native signers were at times unable to identify any relevant signs on the basis of the first gate of the target sign, and thus responded with a gesture rather than an ASL sign. This was not the case for native signers. Native signers nearly always had a potential sign in mind that could match the sensory input even when that input was extremely minimal. Gestured responses appeared to be an attempt to recreate the phonological shape of the stimulus in order to rehearse the stimulus or explore possible continuations of the sign form. It may be the case that non-native signers hoped to activate the sign through kinesthetic feedback instead of relying solely on perceptual input.

The results of this study conflict with previous ASL gating studies in two respects. First, our participants were able to correctly identify the target signs somewhat faster than was reported by either Clark & Grosjean (1982) or Emmorey & Corina (1990), and our participants identified handshape as soon as or earlier than location in contrast to these prior studies. One explanation for these differences may be that the stimuli were not produced in a list format as in Emmorey & Corina's study; the stimuli for this experiment were extracted from a signed sentence following Clark & Grosjean. Thus, it is possible that the hands were closer to the target location and already in the target handshape at the onset of the stimulus than in Emmorey & Corina's study. Moreover, our study differed because the first gate consisted of four frames, or 128 ms, whereas prior studies used a first gate consisting of 1 frame, or 33 ms. We wanted the initial stimulus to be dynamic rather than static. This difference in methodology may have influenced our results by giving participants more time for perceptual integration of the sensory input prior to supplying their first response. Alternatively, differences in the identification of location and handshape may exist in the first 128 ms of stimulus presentation. Additional studies using more fine-grained analyses or alternative methods will be necessary to determine the unique contributions of these parameters to sign recognition. Orfanidou, Adam, McQueen & Morgan (2009), for example, have used the sign spotting task to evaluate the relative contributions of the location, movement and handshape parameters to sign recognition. They report that non-native signers of British Sign Language (BSL) are more likely to substitute handshapes than native signers when misperceiving nonce signs as actual BSL signs, suggesting that location and movement play a more fundamental role in sign recognition for non-native signers. Note however, that responses on the two tasks are made at different points in the recognition process. Thus, future work is needed that taps subtle changes over time in the way that signers constrain their lexical choices on the basis of phonological input.

Our results also indicate that there are some minor but important differences between hearing L2 and deaf non-native signers. Both groups are slower than native signers to identify ASL signs, but the hearing L2 signers appear to make better use of location and movement to narrow the range of signs associated with the sign onset. Although they responded with just as many non-target signs as the deaf non-native signers after the first gate, these signs formed a tighter phonological cluster around the target sign. This is an interesting and somewhat surprising result given the outcome of Study 1, in which the hearing L2 signers were less accurate in their monitoring of handshape and location relative to the non-native signers. Past studies reporting superior language processing by L2 signers relative to non-native L1 signers have explained those results as largely due to the use of top-down processing to improve somewhat weaker bottom-up processing abilities. In the context of sentence repetition and shadowing, for example, Mayberry (1993) has proposed that L2 learners may rely on semantic and syntactic skills to improve sign recognition. However, in the current task, these constraints are not available. Thus, the relative performance of these groups on this task suggests a more fundamental difference in sign recognition abilities; rather than indicating the use of compensatory strategies by L2 learners, the results may underscore the fact that an overreliance on handshape as an entry into the lexicon is unique to deaf non-native signers who do not develop lexical recognition skills in early childhood.

In sum, the results of Study 2 indicate that deaf non-native signers sometimes have difficulty identifying appropriate signs to match incoming perceptual input, but when they do identify possible signs in response to input, those signs are most often identified on the basis of handshape information. Hearing L2 signers are no faster than deaf non-native signers to identify the appropriate sign. But interestingly, prior to sign recognition, hearing L2 signers are more likely to consider lexical candidates that match the perceptual signal in location and movement than deaf non-native signers. Native signers require the least phonetic input to identify the target sign, and their lexical search differs most from non-native signers in their ability to identify lexical candidates matching the input in both handshape and location parameters.

General Discussion

There are relatively few published studies investigating sign language perception and sign recognition, and fewer still that consider how differences in early acquisition profiles may impact these abilities. The results of our studies replicate and extend the finding that restricted linguistic input in early development affects language processing abilities even after decades of language use. Non-native signers who did not benefit from language exposure in early childhood differ in language processing relative to native signers, and are also unique when compared to L2 learners. Prior work has documented difficulties in comprehension for deaf non-native signers relative to deaf native signers (Emmorey et al., 1995; Mayberry & Eichen, 1991; Newport, 1990), and relative to L2 learners of ASL (Mayberry, 1993; Mayberry & Lock, 2003). We considered several possible explanations of these difficulties in comprehension, including disruptions in sign perception that have cascading effects on sign recognition and subsequent stages of processing (Mayberry & Eichen, 1991), versus intact perception but disrupted sign recognition abilities, or a combination of these problems (cf. Mayberry, 2007). The present work clarifies the nature of the comprehension difficulties of deaf non-native signers by providing a direct comparison of performance on a monitoring task and a sign recognition task in the same population of signers.

Deaf non-native signers differ from both hearing L2 signers and deaf native signers in both domains of investigation, but whereas they outperform the other groups on the perception task, they are clearly the weakest group on the sign recognition task. The combined results across the two studies provide the most revealing insights into how restricted language exposure in early development may impact language processing in adulthood. Results of both studies point to a special role for handshape in non-native sign language processing. The non-native signers were significantly faster and more accurate in their detection of handshapes on the monitoring task, and their sign recognition performance indicated a reliance on handshape to search the lexicon. Handshape may be a preferred phonological entry point to the ASL lexicon for non-native signers because it is more static than movement and location, and thus more perceptually stable, or possibly because handshape is more iconically-motivated, and thus semantically rich than location or movement. These possibilities require further investigation. Signers who have been exposed to ASL from early development have been argued to be insensitive to the iconic motivation of the signs they are learning (Meier, 1987; Morgan, Herman, Barriere, & Woll, 2008; Orlansky & Bonvillian, 1984; but see also Wilcox, 2004), but similar studies have yet to be completed with non-native signers. Particularly in the case of non-native signers who were first exposed to ASL in late childhood when they are cognitively much more mature than infants, the earliest experiences with signs are made in the context of communication rather than, as is the case for infants, passive observations of the phonotactically permissable forms of the language in the absence of referential communication (Morford & Mayberry, 2000). Thus, form-meaning relationships will be established prior to the discovery of the sub-lexical patterns that are recurrent across the lexicon.

Another factor that is likely to influence the development of the lexicon in non-native signers concerns the type of language input they receive once they finally begin to learn a signed language. Native signers are likely to have regular exposure to other native signers, among their family members if not also through more frequent involvement in the Deaf community. Non-native signers, by contrast, are more likely to have non-native signers (e.g., parents, teachers, peers) as their primary sources of language input. If signs are more often produced in semantically anomalous ways by non-native than by native signers (Johnson, Liddell & Erting, 1989), then the signed interactions used to generate lexical networks will be much more variable for non-native signers. Compounding the issue of the demographics of the signing community is the fact that non-native signers are more likely to identify signs incorrectly, and hence to activate signs in semantically anomalous contexts (Mayberry & Fischer, 1989; Mayberry & Eichen, 1991). This combination of variability in both input and uptake could be counterproductive to the generation of efficient lexical networks that are form-based, and encourage non-native signers to rely on semantics more than form during face-to-face communication.

Our results may on first reflection appear counter-intuitive in comparison to the spoken language learning literature that has consistently shown poorer perceptual processing for non-native learners relative to native learners (Baker, Trofimovich, Flege, Mack, & Halter, 2008; Kuhl, Williams, Lacerda, Stevens, & Lindblom, 1992). However, difficulty with non-native phoneme perception has been attributed to the assimilation of non-native contrasts to native language contrasts (e.g., Best, 1990; Iverson, Kuhl, & Akahane-Yamada, 2003; Polka, 1995). There is no a priori reason to assume that non-native signers would have prior phonological representations, for example of gesture or homesigns (Goldin-Meadow, 2003; Morford, 2000). Even if they did, and this is a possibility worth investigating (Brentari, Coppola, Massoni & Goldin-Meadow, 2010), these representations would have emerged across childhood rather than being established within the first year of life as is the case in spoken language development. Our interpretation that non-native perception of handshape and location is largely intact despite late onset is consistent with the findings of two other recent studies that report excellent discrimination of selected handshape contrasts in deaf non-native signers (Best et al., 2010; Morford et al., 2008). In the context of understanding the impact of delayed language exposure on language comprehension, our results and those of prior studies suggest that differences in perception alone cannot explain the superior comprehension performance of native signers relative to non-native signers.

We are not the first to propose a relationship between language input and language proficiency (Hart & Risley, 1995; Hoff, 2003; Huttenlocher, Haight, Bryk, Seltzer & Lyons, 1991; Pine, Lieven & Rowland, 1997). Indeed, there is now considerable evidence that changes in the speed of word recognition in the second year of life are associated with individual variability in vocabulary growth at 24 months, and that both of these measures can be predicted longitudinally by natural variations in the amount of maternal talk to young children (Fernald, Perfors & Marchman, 2006; Hurtado, Marchman & Fernald, 2008). Moreover, Marchman & Fernald (2008) demonstrated that word recognition abilities and vocabulary size at these younger ages predict language abilities at 8 years. While we have no way to estimate the vocabulary size of our participants in childhood, the non-native signers in our study most certainly had even more restricted input during these early years of development than hearing children with slower spoken language developmental trajectories. Our study suggests that restricted exposure to language results in a long-term processing deficit that further restricts uptake of the language once language exposure does begin (Morford, 2002). Further, even decades of experience using a signed language as the primary language cannot redress differences in acquisition in early childhood. Whether these long-term differences also apply to children with only minor variations in language exposure in childhood remains to be seen.

By this account, one could argue that the hearing L2 learners should also exhibit similar problems in sign recognition since they also were not exposed to signs in early development. However, L2 learners can and do typically rely on L1 knowledge during L2 word recognition (Sunderman & Kroll, 2006), particularly prior to full proficiency in the second language. Thus, the L2 signers may have been able to rely on prior lexical organization during the development of their L2 lexical processing strategies. The L2 learners are indeed slower to recognize signs than native signers, but they are better able to benefit from the perceptual input to constrain the nature of their lexical search than are the non-native signers.

Some limitations of the current studies are related to the absence of two critical resources for psycholinguists investigating signed language processing. First, although we know that frequency affects lexical processing in signed languages (Emmorey, 2002; Carreiras, Gutierrez-Sigut, Baquero, & Corina, 2008), there are no published frequency ranges for ASL signs (but see Morford & MacFarlane, 2003). Even more critical to the psycholinguistic study of signed languages are assessment tools to evaluate the signing skills of participants. Given the variability in access to language among signers, it is particularly important that we have independent means to evaluate proficiency in various signed languages. No assessment tools were publicly available at the onset of this study, but there are assessment tools for ASL currently under development (e.g., Hauser, Paludneviciene, Supalla, & Bavalier, 2008). Such tools will greatly enhance our ability to investigate the relationship between acquisition profiles in early childhood and language proficiency in adulthood.

Table 1.

Response latencies in milliseconds (standard error) by group and condition

| Familiar | Novel | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Handshape | Location | Handshape | Location | |

| Deaf native signers (n=12) | 769 (13) | 722 (16) | 882 (14) | 818 (14) |

| Deaf non-native signers (n=12) | 763 (15) | 816 (21) | 858 (16) | 927 (21) |

| Hearing L2 signers (n=12) | 805 (18) | 805 (17) | 952 (17) | 929 (19) |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants of our research, as well as Sarah Hafer and Joshua Staley for help in collecting data, and Gabriel Waters for assistance with data analysis. Portions of this study were presented at the 2006 Meeting of the Linguistic Society of America in Albuquerque, NM, the 2009 VL2 Presentation Series at Gallaudet University, and the University of Hamburg's SFB 538 Center for Multilingualism. This research was supported by NIH Grant R03 DC03865 to Jill P. Morford and in part by the National Science Foundation Science of Learning Center Program, under cooperative agreement number SBE-0541953. The writing of the manuscript was completed while the first author was a Visiting Researcher at the SFB 538 Center for Multilingualism, University of Hamburg. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the National Science Foundation. We sincerely thank colleagues, meeting participants, and especially three anonymous reviewers and the journal editor for their insights and constructive feedback on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Appendix 1

Practice items:

HEARING

HOME

NIGHT

CLASS

NAME

Test items:

GIRL

ORAL

PUNISH

INTERESTING

AWFUL

BROTHER

CALIFORNIA

REMEMBER

SEE

MISCHEVIOUS

NONE

OLD

PRINCIPAL

TALK

USE

BUILDING

CHANGE

HIGH

SCHOOL

BEAUTIFUL

BORING

ENJOY

EXPERIENCE

FAMILY

KNOW

LAST

OTHER

PART

QUIET

SISTER

STAY

Footnotes

Manuscript under review. Please do not duplicate, distribute or cite without permission of the authors.

Not all individuals with hearing loss participate in the sociolinguistic community made up of individuals who identify themselves as deaf, and who most typically use a signed language and socialize with other deaf individuals. Thus, a capitalized `D' is used to distinguish the sociolinguistic community from the usage of `deaf' as a reference to hearing loss (Padden & Humphries, 1988).

The sociolinguistics of communities of signers is quite distinctive from communities of speakers. Many signers are exposed to signed language through peers rather than through parents. If this is the first language in which functional competence is achieved, signers may consider ASL their native language even if they did not learn it in the home, or from birth.

Phonological models of signed languages identify four phonological parameters in the sub-lexical structure of signs: Handshape (the form of the hand), Location (the position on the body or in neutral space where a sign is articulated), Orientation (the direction of the palm of the hand), and Movement (the path of movement of the hands during the sign) (Stokoe, Casterline & Croneberg, 1965; Battison, 1978).

References

- Baker W, Trofimovich P, Flege J, Mack M, Halter R. Child-adult differences in second-language phonological learning: The role of cross-language similarity. Language and Speech. 2008;51(4):317–342. doi: 10.1177/0023830908099068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battison R. Lexical borrowing in American Sign Language. Linstok Press; Silver Spring, MD: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Best CT. Adult perception of nonnative contrasts differing in assimilation to native phonological categories. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1990;88:S177. [Google Scholar]

- Best CT, Mathur G, Miranda KA, Lillo-Martin D. Effects of sign language experience on categorical perception of dynamic ASL pseudosigns. Attention, Perception & Psychophysics. 2010;72(3):747–762. doi: 10.3758/APP.72.3.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreault P, Mayberry RI. Grammatical processing in American Sign Language: Age of first-language acquisition effects in relation to syntactic structure. Language and Cognitive Processes. 2006;21(5):608–635. [Google Scholar]

- Brentari D, Coppola M, Mazzoni L, Goldin-Meadow S. When does a system become phonological? Handshape production in gesturers, signers, and homesigners. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s11049-011-9145-1. accepted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chute D. PowerLaboratory for Macintosh. Brooks/Cole; Pacific Grove, CA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Clahsen H, Felser C. How native-like is non-native language processing? TRENDS in Cognitive Sciences. 2006;10(12):564–570. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LE, Grosjean F. Sign recognition processes in American Sign Language: The effect of context. Language and speech. 1982;25(4):325–340. [Google Scholar]

- Carreiras M, Gutierrez-Sigut E, Baquero S, Corina D. Lexical processing in Spanish Sign Language (LSE) Journal of Memory and Language. 2008;58:100–122. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler A, Otake T. Mora or phoneme? Further evidence for language-specific listening. Journal of Memory & Language. 1994;33:824–844. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra A, Van Heuven WJB. The architecture of the bilingual word recognition system: From identification to decision. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2002;23:175–197. [Google Scholar]

- Emmorey K. Language, cognition, and the brain: Insights from sign language research. Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Emmorey K, Bellugi U, Frederici A, Horn P. Effects of age of acquisition on grammatical sensitivity: Evidence from on-line and off-line tasks. Applied Psycholinguistics. 1995;16:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Emmorey K, Corina D. Lexical recognition in sign language: Effects of phonetic structure and morphology. Perceptual and motor skills. 1990;71:1227–1252. doi: 10.2466/pms.1990.71.3f.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A, Perfors A, Marchman VA. Picking up speed in understanding: Speech processing efficiency and vocabulary growth across the second year. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:98–116. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foss DJ, Swinney DA. On the psychological reality of the phoneme: Perception, identification, and consciousness. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1973;12:246–257. [Google Scholar]

- Fukkink R, Hulstijn J, Simis A. Does training in second-language word recognition skills affect reading comprehension? An experimental study. Modern Language Journal. 2005;89(1):54–75. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow S. The resilience of language. Psychology Press; Philadelphia. PA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean F. Sign and word recognition: A first comparison. Sign Language studies. 1981;32:195–220. [Google Scholar]

- Hart B, Risley TR. Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Brookes Publishing Co.; Baltimore, MD: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser P, Paludneviciene R, Supalla T, Bavalier D. American Sign Language-Sentence Reproduction Test: Development and Implications. In: de Quadros RM, editor. Sign Language: Spinning and unraveling the past, present and future. Editora Arara Azul; Petropolis, Brazil: 2008. pp. 160–172. [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt UC, Corina DP. Phonological similarity in American Sign Language. Language and Cognitive Processes. 2002;17(6):593–612. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff E. The specificity of environmental influence: Socioeconomic status affects early vocabulary development via maternal speech. Child Development. 2003;74:1368–1378. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado N, Marchman V, Fernald A. Does input influence uptake? Links between maternal talk, processing speed and vocabulary size in Spanish-learning children. Developmental Science. 2008;11(6):F31–FF39. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00768.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher J, Haight W, Bryk A, Seltzer M, Lyons T. Vocabulary growth: Relation to language input and gender. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:236–248. [Google Scholar]

- Iverson P, Kuhl PK, Akahane-Yamada R. A perceptual interference account of acquisition difficulties for non-native phonemes. Cognition. 2003;87(1):B47–B57. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(02)00198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RE, Liddell SK, Erting CJ. Gallaudet Research Institute Working/Occasional Paper Series, No. 89-3. Gallaudet University Research Institute; Washington, DC: 1989. Unlocking the curriculum: Principles for achieving access in deaf education. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl PK, Williams KA, Lacerda F, Stevens KN, Lindblom B. Linguistic experience alters phonetic perception in infants by 6 months of age. Science. 1992;255:606–608. doi: 10.1126/science.1736364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchman VA, Fernald A. Speed of word recognition and vocabulary knowledge in infancy predict cognitive and language outcomes in later childhood. Developmental Science. 2008;11:F9–F16. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00671.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marslen-Wilson WD. Functional parallelism is spoken word recognition. Cognition. 1987;25:71–102. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(87)90005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry RI. First-language acquisition after childhood differs from second-language acquisition: The case of American Sign Language. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1993;36:1258–1270. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3606.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry RI. The importance of childhood to language acquisition: Insights from American Sign Language. In: Goodman JC, Nusbaum HC, editors. The development of speech perception: The transition from speech sounds to words. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1994. pp. 57–90. [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry RI. When timing is everything: Age of first-language acquisition effects on second-language learning. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2007;28:537–549. [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry RI, Eichen E. The long-lasting advantage of learning sign language in childhood: Another look at the critical period for language acquisition. Journal of Memory and Language. 1991;30:486–512. [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry RI, Fischer SD. Looking through phonological shape to lexical meaning: The bottleneck of non-native sign language processing. Memory & Cognition. 1989;17(6):740–754. doi: 10.3758/bf03202635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberry RI, Lock E. Age constraints on first versus second language acquisition: Evidence for linguistic plasticity and epigenesis. Brain and Language. 2003;87:369–383. doi: 10.1016/s0093-934x(03)00137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier RP. Elicited imitation of verb agreement in American Sign Language: Iconically or morphologically determined? Journal of Memory & Language. 1987;26(3):362–376. [Google Scholar]

- Morford JP. Delayed phonological development in ASL: Two case studies of deaf isolates. Recherches linguistiques de Vincennes. 2000;29:121–142. [Google Scholar]

- Morford JP. Why does exposure to language matter? In: Givón T, Malle B, editors. The evolution of language from pre-language. Benjamins; Amsterdam: 2002. pp. 329–341. [Google Scholar]

- Morford JP. Grammatical development in adolescent first-language learners. Linguistics. 2003;41(4):681–721. [Google Scholar]

- Morford JP, Grieve-Smith AB, MacFarlane J, Staley J, Waters GS. Effects of language experience on the perception of American Sign Language. Cognition. 2008;109:41–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morford JP, MacFarlane J. Frequency characteristics of American Sign Language. Sign Language Studies. 2003;3:2, 213–225. [Google Scholar]

- Morford JP, Mayberry RI. A reexamination of “early exposure” and its implications for language acquisition by eye. In: Chamberlain C, Morford JP, Mayberry RI, editors. Language acquisition by eye. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2000. pp. 111–127. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan G, Herman R, Barriere I, Woll B. The onset and mastery of spatial language in children acquiring British Sign Language. Cognitive Development. 2008;23:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Newport Elissa L. Maturational constraints on language learning. Cognitive Science. 1990;14:11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Orfanidou E, Adam R, McQueen JM, Morgan G. Making sense of nonsense in British Sign Language (BSL): The contribution of different phonological parameters to sign recognition. Memory & Cognition. 2009;37(3):302–317. doi: 10.3758/MC.37.3.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlansky M, Bonvillian J. The role of iconicity in early sign language acquisition. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1984;49:287–292. doi: 10.1044/jshd.4903.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padden C, Humphries T. Deaf in America: Voices from a Culture. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Pine JM, Lieven EVM, Rowland CF. Stylistic variation at the `single-word stage': Relations between maternal speech characteristics and children's vocabulary composition and usage. Child Development. 1997;64:807–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polka L. Linguistic influences in adult perception of non-native vowel contrasts. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1995;97:1286–1296. doi: 10.1121/1.412170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack I, Pickett JM. The intelligibility of excerpts from conversation. Language and Speech. 1963;6:165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Scherag A, Demuth L, Rösler F, Neville H, Röder B. The effects of late acquisition of L2 and the consequences of immigration on L1 for semantic and morpho-syntactic language aspects. Cognition. 2004;93(3):B97–b108. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastián-Gallés N, Echeverria S, Bosch L. The influence of initial exposure on lexical representation: Comparing early and simultaneous bilinguals. Journal of Memory and Language. 2005;52:240–255. [Google Scholar]

- Stokoe W, Casterline D, Croneberg C. A dictionary of American Sign Language on linguistic principles. Gallaudet College Press; Washington, DC: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox S. Cognitive iconicity: Conceptual spaces, meaning and gesture in signed languages. Cognitive Linguistics. 2004;15(2):119–147. [Google Scholar]