Abstract

Systemic signals induced by wounding and/or pathogen or herbivore attack may be realized by either chemical or mechanical signals. In plants a variety of electrical phenomena have been described and may be considered as signal-transducing events; such as variation potentials (VPs) and action potentials (APs) which propagate over long distances and hence are able to carry information from organ to organ. In addition, we recently described a new type of electrical long-distance signal that propagates systemically, i.e., from leaf to leaf, the “system potential” (SP). This was possible only by establishing a non-invasive method with micro-electrodes positioned in substomatal cavities of open stomata and recording apoplastic responses. Using this technical approach, we investigated the function of the peptaibole alamethicin (ALA), a channel-forming peptide from Trichoderma viride, which is widely used as agent to induce various physiological and defence responses in eukaryotic cells including plants. Although the ability of ALA to initiate changes in membrane potentials in plants has always been postulated it has never been demonstrated. Here we show that both local and long-distance electrical signals, namely depolarization, can be induced by ALA treatment.

Key words: alamethicin, long distance electrical signal, depolarization, non-invasive recording

Peptaibols are linear membrane active peptide antibiotics produced by various fungi.1,2 They are characterized by the presence of an unusual amino acid, α-aminoisobutyric acid, and a C-terminal hydroxylated amino acid and are generated by non-ribosomal peptide synthetases.2,3 Due to their amphiphilic nature they self-associate into oligomeric ion-channels that span the width of lipid bilayer membranes.3 Peptaibols exhibit antibiotic activity against bacteria and fungi, tissue damage in insect larvae, as well as cytolytic activity towards mammalian cells.2 ALA is a voltage-gated ion channel-forming peptide mixture that consists of at least 12 compounds each containing 20 amino acid residues.1,2 This peptaibole is often used to elicit typical systemic responses in plants, many of which are in the context of indirect defences, such as the induction and accumulation of secondary metabolites in general, volatile compounds, and the phytohormones jasmonic acid and salicylic acid but also tendril coiling is induced.4–7 Moreover, ALA has been shown to permeabilize mitochondria and the plasma membrane of tobacco suspension culture cells but not the tonoplast for small molecules.8 Thus, ALA is a valuable tool in plant science but its primary biological activity in plant tissues has never been shown experimentally.

Because of the channel-forming properties of ALA, effects on the membrane potential of cells are very likely. Therefore, to monitor ALA application-elicited electrical signals, we employed the non-invasive method with microelectrodes placed in the apoplasm of the sub-stomatal cavities of open stomata. Whereas electrical signals in plants such as action potentials and variation potentials have been well documented in literature,9 this particular approach has been successfully applied for the detection and characterization of the novel system potentials.10,11 With an intracellular recording the depolarization of a membrane occurs when the cell interior becomes less negative; whereas for the apoplastic recording used here, the inverse argument holds true. To avoid confusion, we follow the convention and call an apoplastic hyperpolarization a depolarization.10,11

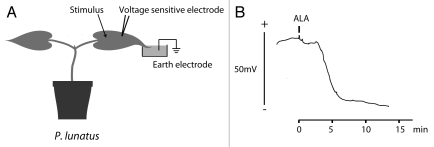

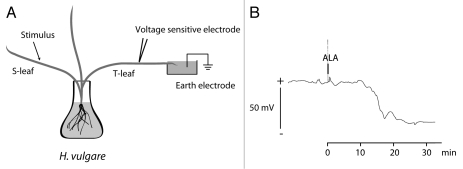

ALA (mixture of several isoforms purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) was tested on the dicotyledonous lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus L.) and the monocotyledonous barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). As shown in Figure 1, upon a 5 nM ALA stimulus a 40 mV depolarization was induced and detected at a distance of 5 cm on the same leaf in lima bean. Systemic electric propagation was tested and demonstrated in barley (Fig. 2). We used barley for these experiments because we learned from earlier studies that electrical signals are not propagated between the primary leaves of lima bean whereas in barley electrical signals pass nodes and internodia more easily. Application of 25 nM ALA on one leaf (S-leaf) resulted in a 45 mV depolarization response at a distant of 25 cm on a different leaf (T-leaf), indicating that ALA induced a systemic electrical response that moved from one to the other leaf. In both plants the velocity of the propagating depolarization signal was calculated to be 2.5 cm min−1. Whereas these results basically demonstrate the ability of ALA to initiate electrical signals in plant tissues both locally and systemically, the molecular interconnections between these electrical phenomena, the induction and synthesis of phytohormones as well as secondary metabolites, and how the ALA signal is transduced mechanistically, remains to be elucidated.

Figure 1.

Local response of Phaseolus lunatus to Alamethicin. (A) Experimental setup for the measurement of apoplastic voltage changes using microelectrodes positioned in the sub-stomatal cavities of P. lunatus.11 Stimuli and measurements of apoplastic voltage changes were performed on the same leaf with a distance of approximately 5 cm. The tip of the leaf was submerged in 5 mM KCl with 0.1 mM CaCl2, pH 5, and the solution was connected to earth with a reference electrode filled with 0.5 M KCl. (B) The voltage response to 5 nM Alamethicin (ALA) (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) added to a cut injury of the P. lunatus leaf at the indicated time shows a hyperpolarization of the apoplast (negative shift of the apoplastic potential), suggesting depolarization of the symplast. A typical recording of one out of three independent experiments is presented.

Figure 2.

Systemic response of Hordeum vulgare to Alamethicin. (A) Experimental setup for the measurement of apoplastic voltage changes using microelectrodes positioned in the sub-stomatal cavities of H. vulgare.11 Stimuli were applied to one leaf (Stimulus leaf, S-leaf), and measurements of apoplastic voltage changes were performed on a second leaf (Target leaf, T-leaf) with a distance of approximately 25 cm. The tip of the T-leaf was submerged in 5 mM KCl with 0.1 mM CaCl2, pH 5, and the solution was connected to earth with a reference electrode filled with 0.5 M KCl. (B) The voltage response to 25 nM Alamethicin (ALA) (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) added to a cut injury of the H. vulgare S-leaf at the indicated time shows a hyperpolarization of the apoplast (negative shift of the apoplastic potential), suggesting depolarization of the symplast. A typical recording of one out of three independent experiments is presented.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/12223

References

- 1.Brewer D, Mason FG, Taylor A. The production of alamethicins by Trichoderma spp. Can J Microbiol. 1987;33:619–625. doi: 10.1139/m87-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leitgeb B, Szekeres A, Manczinger L, Vagvölgyi C, Kredics L. The history of alamethicin: A review of the most extensively studied peptaibol. Chem Biodivers. 2007;4:1027–1051. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200790095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chugh JK, Wallace BA. Peptaibols: Models for ion channels. Biochem Soc Transact. 2001;29:565–570. doi: 10.1042/bst0290565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruinsma M, Baoping P, Mumm R, van Loon JJA, Dicke M. Comparing induction at an early and late step in signal transduction mediating indirect defence in Brassica oleracea. J Exp Bot. 2009;60:2589–2589. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engelberth J, Koch T, Kuhnemann F, Boland W. Channel-forming peptaibols are potent elicitors of plant secondary metabolism and tendril coiling. Angewandte Chem Internat Ed. 2000;39:1860–1862. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(20000515)39:10<1860::aid-anie1860>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engelberth J, Koch T, Schüler G, Bachmann N, Rechtenbach J, Boland W. Ion channel-forming alamethicin is a potent elicitor of volatile biosynthesis and tendril coiling. Cross talk between jasmonate and salicylate signaling in Lima bean. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:369–377. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.1.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viterbo A, Wiest A, Brotman Y, Chet I, Kenerley C. The 18mer peptaibols from Trichoderma virens elicit plant defence responses. Mol Plant Pathol. 2007;8:737–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matic S, Geisler DA, Møller IM, Widell S, Rasmusson AG. Alamethicin permeabilizes the plasma membrane and mitochondria but not the tonoplast in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L. cv Bright Yellow) suspension cells. Biochem J. 2005;389:695–704. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies E. Electrical signals in plants: facts and hypotheses. In: Volkov AG, editor. Plant Electrophysiology. Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg, New York; 2006. pp. 407–422. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felle HH, Zimmermann MR. Systemic signalling in barley through action potentials. Planta. 2007;226:203–214. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0458-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zimmermann MR, Maischak H, Mithöfer A, Boland W, Felle HH. System potentials, a novel electrical long-distance apoplastic signal in plants, induced by wounding. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:1593–1600. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.133884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]