Abstract

We recently reported that H2S could significantly promote the germination of wheat grains subjected to aluminum (Al3+) stress.1 In these experiments seeds were pretreated with the H2S donor NaHS for 12 h prior to Al3+ stress. During this pre-incubation period we observed that H2S increased the activity of grain amylase in the absence of Al3+. Using embryoless half grains of wheat we now show that H2S preferentially affects the activity of endosperm β-amylase and that α-amylase synthesis and activity is unaffected by this treatment.

Key words: α-amylase, β-amylase, hydrogen sulfide, reactive sulfur species, seed germination, wheat (triticum)

Cereal grains contain many acid hydrolases, some synthesized de novo by the scutellum and aleurone layer and others are found preformed in the starchy endosperm. The amylases are the best known of these types of enzymes. α-Amylases are synthesized and secreted by the scutellum and aleurone layer, and in the case of aleurone isoforms their synthesis is regulated by GAs and ABA.2,3 Whereas GAs stimulate the synthesis of α-amylases and many other secreted hydrolases, ABA inhibits these processes. β-Amylases, on the other hand, are preformed enzymes whose synthesis is not affected by ABA and GAs. Two forms of β-amylase are found in wheat grains, one is a soluble form present in ungerminated grains which can form high-molecular-weight homopolymers or heteropolymers; the other is bound in an inactive form via S-S linkages to proteins at the periphery of starch grains.4,5 The activation of β-amylases is thought to result at least in part from their release from endosperm proteins by the action of GA-induced proteases secreted from the aleurone layer.6

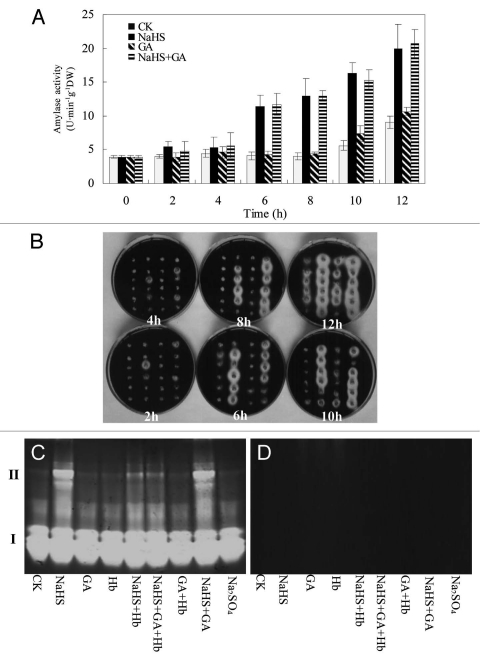

To examine in more detail the effect of H2S on wheat grain amylases we used de-embryontated wheat grains where only the aleurone layer and starchy endosperm were the possible sources of amylase activity. Embryoless half grains of wheat (Triticum aestivum L., c.v Yangmai 158) were incubated in water, the H2S donor NaHS, GA, or combinations of these treatments for up to 12 h. After incubation soluble proteins were isolated from grains by homogenizing in buffer and amylase activity was determined colorimetrically using starch-I2KI. Figure 1A shows that during the first 8 h of incubation there was no increase in amylase activity from half grains incubated in H2O or GA but there was a small but significant increase in activity after 10 h and 12 h of incubation in these two treatments. By contrast, incubation in NaHS brought about a three-fold increase in amylase activity by six h and this increased to about five-fold above the initial activity by 12 h of incubation.

Figure 1.

Amylolytic activity from wheat half grains measured colorimetrically (A), by diffusion into agar-starch (B) and following native gel electrophoresis (C and D). (A) Half grains were incubated in water (CK), 0.5 mM NaHS, 10 µM GA3 and 0.5 mM NaHS plus 10 µM GA3 for up to 12 h. Amylase activity was measured colorimetrically on grain homogenates by the starch I-KI method. (B) Half grains pre-incubated as (A) then transferred to agar containing 0.2% starch and 2 mM EDT A for a further 12 h. Amylolytic activity was determined by the diameter of the starch-free halo after flooding the agar-starch plate with I-KI solution. Seeds treated with CK, NaHS, GA3 and NaHS plus GA3 were lined from left to right in each plate, respectively. (C and D) Wheat grains incubated for 12 h in H2O, NaHS, GA3 and Hb (0.1 g/L) and combinations of these treatments, were homogenized and aliquots of extracts were electrophoresed by non-denaturing PAGE. After electrophoesis gels were soaked in starch, washed and stained with I-KI. Amylolytic activity is shown by cleared areas in the gel. For the gel in (C), homogentes were incubated with 25 mM EDT A to inactivate α-amylase and for (D), they were heated at 70°C to inactivate β-amylase.

We confirmed these results by incubating wheat half gains on 0.2% agar containing 0.2% soluble starch and 2 mM EDTA (Fig. 1B). In this experiment, half grains were first incubated in H2O, GA or NAHS for up to 12 h as for the experiment shown in Figure 1A and half grains were transferred to agar to estimate amylase activity. Because α-amylases are Ca2+-containing metalloenzymes whose activities are dependent on Ca2+ binding we incorporated EDTA into the agar to favor the appearance of β-amylase activity. The data in Figure 1B confirm what we observed when we measured amylase activity colorimetrically, namely that starch degrading activity was high in half grains exposed to NaHS but low in those incubated in H2O or GA. From this experiment we also concluded that the starch degrading activity was likely a result of the activity of β-amylase as α-amylase activity would have been reduced or eliminated by the presence of EDTA.

We established that the amylolytic activity produced by wheat grains in response to the NaHS donor was largely β-amylase by selectively inhibiting amylase activities following native gel electrophoresis. α-Amylases are heat stable but are sensitive to metal chelators, whereas β-amylases are denatured by heating but are not inhibited by chelators such as EDTA.4 Figure 1C and D show the activities of amylase isoforms measured by incubating non-denaturing polyacrylamide gels in 1% soluble starch followed by staining in I-KI. Figure 1C shows amylolytic activity after incubation of the gel in starch containing 25 mM EDTA. Two distinct sets of bands are seen together with minor bands of activity. Whereas group I amylases do not change significantly following treatment incubation in the presence of NaHS or GA, group II amylases show high activity in the presence of NaHS, but show no activity with GA (Fig. 1C). When the enzyme preparations were heated to 70°C for 15 min before electrophoresis almost all activity was lost showing that the activity seen in the absence of heating but in the presence of EDTA was likely that of β-amylase. We also used hemoglobin (Hb) a nonspecific H2S scavenger to show that the effects of NaHS were indeed via the production of H2S. Figure 1C shows that Hb almost completely abolished the inductive effect of NaHS on β-amylase activity.

Although at present we have no direct evidence that H2S acts as an endogenous regulator of endosperm function in cereal grains, it is tempting to speculate that this is indeed the case. Our previous work showed an increase in the synthesis of H2S by wheat grains that is detected as early as 12 h following the start of imbibition in H2O.1 Although we have no information on the route of H2S synthesis in wheat, there is abundant evidence that plants synthesize H2S as its emission has been observed in many species.7–13 In plants, H2S is thought to be released from cysteine via a reversible O-acetylserine (thiol) lyase (OASTL) reaction, and recently several L- and D-cysteine-specific desulfhydrase candidates have been isolated and partially characterized from Arabidopsis thaliana, confirming H2S release by the action of desulfhydrases in various cellular compartments.14–17 The induction of L-cysteine desulfhydrase upon pathogen attack,18 freezing tolerance by H2S fumigation,19 emission of H2S from plants exposed to SO2 injury,10,20 and abiotic stresses tolerance in plants treated with H2S donor,1,21–24 all infer that H2S is involved in these responses.

It is also tempting to speculate that H2S may work in cereal grains by influencing redox status.15,25 It has been proposed that H2S can bring about an increase in synthesis of glutathione from cysteine and an overall improvement of plant performance under stress. The release of β-amylase from starchy endosperm proteins or the dissociation of free β-amylase from small homopolymers or heteropolymers has been shown to be enhanced by reducing agents such as dithiothreitol and by S-H proteinases. We propose that one plausible action of H2S in cereal endosperm is to enhance reactive sulfur species that can lead to reduction of S-S bonds between β-amylase and its binding partners in the endosperm. Release of activated β-amylase would then be free to participate in starch degradation providing sugar units for seedling growth and development prior to the induction of α-amylases by GAs.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the Great Project of Natural Science Foundation from Anhui Provincial Education Department (ZD200910), and the Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province (070411009).

Abbreviations

- ABA

abscsic acid

- GAs

gibberellins

- H2S

hydrogen sulfide

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/12297

References

- 1.Zhang H, Tan ZQ, Hu LY, Wang SH, Luo JP, Jones R. Hydrogen sulfide alleviates aluminum toxicity in germinating wheat seedlings. J Integr Plant Biol. 2010;52:556–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fincher GB. Molecular and cellular biology associated with endosperm mobilization in germinating cereal grains. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1989;40:305–346. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lovegrove A, Hooley R. Gibberellin and abscisic acid signaling in aleurone. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:102–110. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(00)01571-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forsyth SA, Koebner RMD. Wheat endosperm high molecular weight albumins and β-amylase; genetic and electrophoretic evidence of their identity. J Cereal Sci. 1992;15:137–141. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ziegler P. Cereal β-amylases. J Cereal Sci. 1999;29:195–204. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sopanen T, Laurière C. Release and activity of bound β-amylase in a germinating barley grain. Plant Physiol. 1989;89:244–249. doi: 10.1104/pp.89.1.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson LG, Bressan RA, Filner P. Light-dependent emission of hydrogen sulfide from plants. Plant Physiol. 1978;61:184–189. doi: 10.1104/pp.61.2.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winner WE, Smith CL, Koch GW, Mooney HA, Bewley JD, Krouse HR. Rates of H2S emission from plants and patterns of stable sulphur isotope fractionation. Nature. 1981;289:672–673. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sekiya J, Schmidt A, Wilson LG, Filner P. Emission of hydrogen sulfide by leaf tissue in response to L-cysteine. Plant Physiol. 1982;70:430–436. doi: 10.1104/pp.70.2.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sekiya J, Wilson LG, Filner P. Resistance to injury by sulfur dioxide: Correlation with its reduction to, and emission of, hydrogen sulfide in cucurbitaceae. Plant Physiol. 1982;70:437–441. doi: 10.1104/pp.70.2.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rennenberg H. Role of O-acetylserine in hydrogen sulfide emission from pumpkin leaves in response to sulfate. Plant Physiol. 1983;73:560–565. doi: 10.1104/pp.73.3.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rennenberg H. The fate excess of sulfur in higher plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1984;35:121–153. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rennenberg H, Huber B, Schröder P, Stahl K, Haunold W, Georgii HW. Emission of volatile sulfur compounds from spruce trees. Plant Physiol. 1990;92:560–564. doi: 10.1104/pp.92.3.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leon S, Touraine B, Briat JF, Lobréaux S. The AtNFS2 gene from Arabidopsis thaliana encodes a NifS-like plastidial cysteine desulphurase. Biochem J. 2002;366:557–564. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rausch T, Wachter A. Sulfur metabolism: a versatile platform for launching defence operations. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papenbrock J, Riemenschneider A, Kamp A, Schulz-Vogt HN, Schmidt A. Characterization of cysteine-degrading and H2S-releasing enzymes of higher plants—from the field to the test tube and back. Plant Biol. 2007;9:582–588. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-965424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Álvarez C, Calo L, Romero LC, García I, Gotor C. An O-acetylserine(thiol)lyase homolog with L-cysteine desulfhydrase activity regulates cysteine homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2010;152:656–669. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.147975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bloem E, Riemenschneider A, Volker J, Papenbrock J, Schmidt A, Salac I. Sulphur supply and infection with Pyrenopeziza brassica influence L-cysteine desulfhydrase activity in Brassica napus L. J Exp Bot. 2004;55:2305–2312. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stuiver CEE, De Kok LJ, Kuiper P°C. Freezing tolerance and biochemical changes in wheat shoots as affected by H2S fumigation. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1992;30:47–55. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hällgren JE, Fredriksson SÅ. Emission of hydrogen sulfide from sulfate dioxide-fumigated pine trees. Plant Physiol. 1982;70:456–459. doi: 10.1104/pp.70.2.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang H, Hu LY, Hu KD, He YD, Wang SH, Luo JP. Hydrogen sulfide promotes wheat seed germination and alleviates the oxidative damage against copper stress. J Integr Plant Biol. 2008;50:1518–1529. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang H, Ye YK, Wang SH, Luo JP, Tang J, Ma DF. Hydrogen sulfide counteracts chlorophyll loss in Sweet potato seedling leaves and alleviates oxidative damage against osmotic stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2009;58:243–250. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang H, Jiao H, Jiang CX, Wang SH, Wei ZJ, Luo JP, et al. Hydrogen sulfide protects soybean seedlings against drought-induced oxidative stress. Acta Physiol Plant. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s11738-010-0469-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang H, Wang MJ, Hu LY, Wang SH, Hu KD, Bao LJ, et al. Hydrogen sulfide promotes wheat seed germination under osmotic stress. Russ J Plant Physiol. 2010;57:532–539. (in print) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacob C, Giles GI, Giles NM, Sies H. Sulfur and selenium: the role of oxidation state in protein structure and function. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2003;42:4742–4758. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]