Abstract

Topical microbicides for use by women to prevent the transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other sexually transmitted infections are urgently required. Dendrimers are highly branched nanoparticles being developed as microbicides. SPL7013 is a dendrimer with broad-spectrum activity against HIV type I (HIV-1) and -2 (HIV-2), herpes simplex viruses type-1 (HSV-1) and -2 (HSV-2) and human papillomavirus. SPL7013 [3% (w/w)] has been formulated in a mucoadhesive carbopol gel (VivaGel®) for use as a topical microbicide. Previous studies showed that SPL7013 has similar potency against CXCR4- (X4) and CCR5-using (R5) strains of HIV-1 and that it blocks viral entry. However, the ability of SPL7013 to directly inactivate HIV-1 is unknown. We examined whether SPL7013 demonstrates virucidal activity against X4 (NL4.3, MBC200, CMU02 clade EA and 92UG046 clade D), R5 (Ba-L, NB25 and 92RW016 clade A) and dual-tropic (R5X4; MACS1-spln) HIV-1 using a modified HLA-DR viral capture method and by polyethylene glycol precipitation. Evaluation of virion integrity was determined by ultracentrifugation through a sucrose cushion and detection of viral proteins by Western blot analysis. SPL7013 demonstrated potent virucidal activity against X4 and R5X4 strains, although virucidal activity was less potent for the 92UG046 X4 clade D isolate. Where potent virucidal activity was observed, the 50% virucidal concentrations were similar to the 50% effective concentrations previously reported in drug susceptibility assays, indicating that the main mode of action of SPL7013 is by direct viral inactivation for these strains. In contrast, SPL7013 lacked potent virucidal activity against R5 HIV-1 strains. Evaluation of the virucidal mechanism showed that SPL7013-treated NL4.3, 92UG046 and MACS1-spln virions were intact with no significant decrease in gp120 surface protein with respect to p24 capsid content compared to the corresponding untreated virus. These studies demonstrate that SPL7013 is virucidal against HIV-1 strains that utilize the CXCR4 coreceptor but not viruses tested in this study that solely use CCR5 by a mechanism that is distinct from virion disruption or loss of gp120. In addition, the mode of action by which SPL7013 prevents infection of cells with X4 and R5X4 strains is likely to differ from R5 strains of HIV-1

Keywords: Dendrimer, microbicide, SPL7013, HIV, virucidal activity

UNAIDS (2008) estimates that 33 million people are infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and half of these are women (UNAIDS, 2008). Microbicides are being developed that prevent or reduce transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) when applied to the vagina or rectum (Balzarini and Van Damme, 2007). Microbicide classes include nonspecific surfactants or detergents and acid buffering agents, moderately specific macromolecular anionic polymers that block HIV and other STIs, and HIV specific drugs that inhibit viral entry and reverse transcription (Balzarini and Van Damme, 2007). Proof of concept that a vaginal topical microbicide gel (1% tenofovir gel) can protect women against HIV acquisition has been reported (Abdool Karim et al., 2010).

The development of novel microbicides that are not used for the treatment of HIV and that have dual action against HIV and other STIs including HSV would be desirable since the latter is known to increase HIV acquisition (Brown et al., 2007; Freeman et al., 2006). Dendrimers (dendri- = tree, -mer = branching) are a relatively new class of macromolecule characterized by highly-branched, well-defined, three-dimensional structures that are being developed as a topical microbicide (Rupp et al., 2007). Dendrimer structure-activity relationship studies have revealed that SPL7013 has the greatest potency against both HIV-1 and HSV-2 (Tyssen et al., 2010). SPL7013 is comprised of a divalent benzylhydrylamine core, four generations of L-lysine branches radiating from the core, with the outermost branches capped with 32 naphthalene disulfonic acid (DNAA) surface groups which impart hydrophobicity and a high anionic charge to the dendrimer surface (Tyssen et al., 2010). SPL7013 [3% (w/w)] has been formulated in a mucoadhesive Carbopol®-based aqueous gel (SPL7013 Gel, VivaGel®) for use as a topical vaginal microbicide (Rupp et al., 2007; Tyssen et al., 2010).

SPL7013 demonstrates broad-spectrum activity against a wide-range of HIV-1 clades and HIV-2 in vitro (Gong et al., 2005; Lackman-Smith et al., 2008; Tyssen et al., 2010), is active against HIV-1 in explant cultures (Abner et al., 2005; Cummins et al., 2007), blocks HIV-1 infection in vitro in the presence of serum and cervicovaginal secretions (Tyssen et al., 2010), and retains HIV-1 inhibitory activity in seminal plasma (Lackman-Smith et al., 2008). SPL7013 does not specifically enhance HIV-1 replication in vitro (Sonza et al., 2009) and demonstrates low toxicity in cervical and colorectal epithelial cell lines (Dezzutti et al., 2004). SPL7013 Gel was protective against vaginal challenge with a chimeric simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV89.6P) (Jiang et al., 2005) and is well tolerated in animal models (Bernstein et al., 2003; Patton et al., 2006; Tyssen et al., 2010) and in phase I safety studies (Chen et al., 2009; O'Loughlin et al., 2010).

SPL7013 has similar inhibitory activity against CXCR4-using (X4) and CCR5-using (R5) strains of HIV-1 in cell culture assays by reportedly blocking viral attachment and entry (Lackman-Smith et al., 2008; Tyssen et al., 2010). However, these studies were performed in assays where the direct impact of SPL7013 on HIV-1 infectivity could not be ascertained. In this study we evaluated the ability of SPL7013 to directly inactivate laboratory-adapted and clinical HIV-1 isolates that utilize different chemokine receptors to establish whether SPL7013 has HIV-1 virucidal activity.

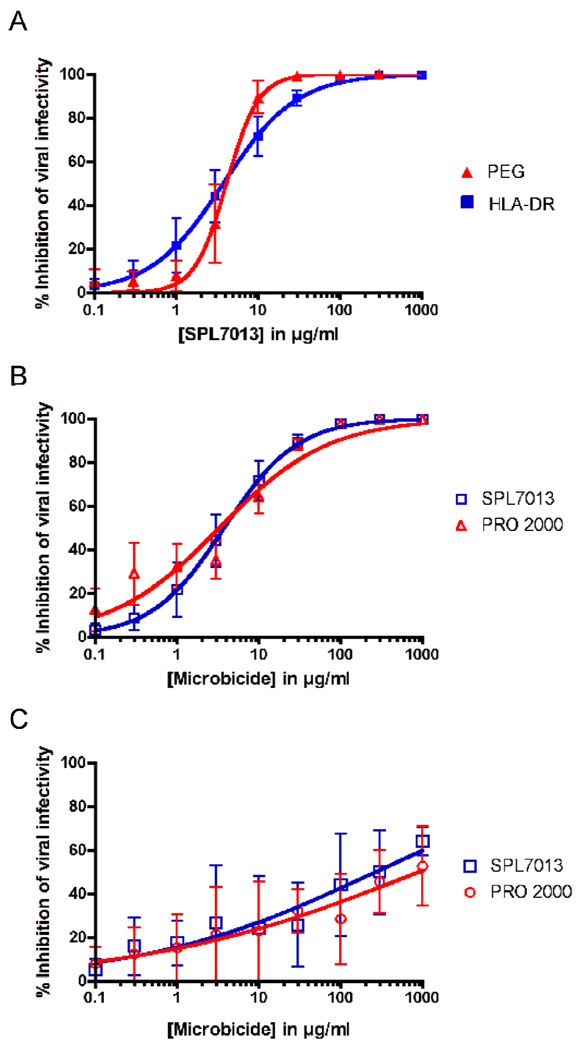

Virucidal activity was determined by solid-phase immobilization of HIV-1 using a HLA-DR monoclonal antibody (L243, ATCC) bound to a 96 well flat-bottom tissue culture plate (Nunc) to capture virus as previously described (Fletcher et al., 2006) with several modifications, most notably the use of TZM-bl cells to quantify HIV-1 infectivity by measuring luciferase activity in cell lysates (Tyssen et al., 2010). To validate the modified HLA-DR capture assay we performed a distinct virucidal assay based on differential polyethylene glycol (PEG) precipitation of virus and by confirming whether the linear polyanion, PRO 2000 previously shown to have virucidal activity against an X4 but not an R5 laboratory isolate (Fletcher et al., 2006), was virucidal against X4 in the modified HLA-DR capture method. Incubation of NL4.3 with SPL7013 for 1 h at 37°C followed by either HLA-DR capture or PEG precipitation revealed similar SPL7013 50% virucidal concentrations (VC50 ± SE) [4.6 ± 1.9 µg/ml (n=3) and 4.5 ± 2.0 µg/ml (n=3), respectively] (Figure 1A). The PRO 2000 positive control demonstrated NL4.3 virucidal activity in the HLA-DR capture method (VC50 = 4.3 ± 2.0 µg/ml, n=3) with a similar potency compared to SPL7013 (4.5 ± 2.0 µg/ml, n=3) (Figure 1B). Both PRO 2000 and SPL7013 lacked virucidal activity against NB25, an early R5 HIV-1 strain (Tyssen et al., 2010) with VC50 values of 890 and 270 µg/ml, respectively (Figure 1C). Taken together, these data validate the modified HLA-DR capture assay for the determination of SPL7013 virucidal activity, which was used in the subsequent experiments. In addition they show that PRO 2000 and SPL7013 have similar virucidal activity against an X4 laboratory strain and dramatically less activity against a R5 clinical isolate.

Figure 1. SPL7013 virucidal activity against NL4.3 by HLA-DR capture and PEG precipitation.

(A). Comparison of the SPL7013 virucidal activity against NL4.3 as measured by HLA-DR capture and PEG precipitation. The HLA-DR capture method was performed as published previously (Fletcher et al., 2006) with the following modifications. After incubation with SPL7013 or PRO 2000, plates were washed 5 – 6 times with Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin and 2 mM glutamine (DMEM-10) to remove microbicide. TZM-bl cells were then added (2.5 × 105/well) to quantify HIV-1 infectivity by measuring luciferase activity in cell lysates as published (Tyssen et al., 2010). Sufficient virus, grown in PHA-stimulated PBMC, was used to yield ≥100,000 relative light units (RLU; virus titers 2 × 105 – 1 × 106 infectious units/ml, depending on strain). PEG precipitation assays, initially performed with SPL7013 in the absence of HIV-1, established that 3% (w/v) PEG did not precipitate the dendrimer up to 500 µg/ml (data not shown). For assays performed with virus, an equal volume of NL4.3 (sufficient to yield ~100,000 RLU) was mixed with an equal volume of medium containing microbicide. The mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37°C followed by the addition of a half volume of PEG/NaCl [9% PEG 6000 (w/v) and 0.5 M NaCl] and overnight incubation at 4°C. HIV-1 was pelleted by centrifugation in a microfuge at 13,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature. Supernatant was removed and the pellets resuspended in DMEM-10 and added to wells seeded with TZM-bl cells. Luciferase activity was measured after 48 h incubation as described (Tyssen et al., 2010). (B). NL4.3 virucidal activity of SPL7013 compared to PRO 2000 in the HLA DR capture assay. (C). NB25 virucidal activity of SPL7013 compared to PRO 2000 in the HLA DR capture assay. Data for graphs A and B were derived from three independent assays and error bars denote standard error of the mean. For graph C, data were derived from two independent assays and error bars denote the standard error.

We next assessed SPL7013 virucidal activity against the X4 clade B isolate MBC200 (Oelrichs et al., 2000), the clade EA isolate CMU02 (Tyssen et al., 2010), the clade D isolate (92UG046), the R5X4 clade B isolate (MACS1-spln) (Gorry et al., 2001) and three R5 strains (Ba-L, NB25 and the clade A 92RW016 strain) in the HLA-DR capture assay (Table 1). The VC50 values were compared to the 50% effective concentration (EC50) values obtained from drug susceptibility assays previously performed in TZM-bl cells where the dendrimer was present during HIV-1 infection of target cells (Tyssen et al., 2010). SPL7013 had potent virucidal activity against the X4 strains, NL4.3, MBC200 and CMU02 (Table 1). The dendrimer was also virucidal against the X4 92UG046 isolate although the VC50 was 15-fold greater than that observed for NL4.3 (Table 1). The most potent SPL7013 virucidal activity was observed for the R5X4 strain, MACS1-spln (Table 1). The SPL7013 VC50 values for NL4.3, MBC200, CMU02 and MACS1-spln were similar compared to their SPL7013 EC50 values (also determined in TZM-bl cells) (Tyssen et al., 2010) suggesting that the main mode of action for SPL7013 is by direct viral inactivation. In contrast, the SPL7013 VC50 values were the highest for the three R5 strains with the 92RW016 R5 strain demonstrating resistance to SPL7013 activity even up to 1,000 µg/ml (Table 1). In a separate study where SPL7013 virucidal activity was determined using a virucidal suspension test (a test method to assess the activity of microbicides against viruses in suspension, ASTM E1052) incubation of the X4 HIVMN strain with 0.5% (w/w) SPL7013 for 30 sec and 1 min resulted in a 1.8 × 103-fold and 3.2 × 104-fold reduction in HIV-1 infectivity, respectively (assay performed by Biosciences Laboratories Inc, Montana USA). These data are consistent with our observation that SPL7013 is virucidal against X4 HIV-1 strains.

Table 1.

SPL7013 virucidal activity against HIV-1 strains

| HIV Strain |

Clade |

Co- receptor usagea |

Mean SPL7013 EC50 (µg/ml)b |

Mean SPL7013 VC50 (µg/ml)c |

Fold differenced |

V3 loop charge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NL4.3 | B | X4 | 3.3 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 2.0 | 1.4 | +9 |

| 92UG046 | D | X4 | 3.7 ± 1.3 | 67 ± 14 | 18 | +8 |

| MBC200 | B | X4 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 1.5 | 4 | +7 |

| CMU02 | EA | X4 | 1.7 ± 0.7 | 5.6 ± 2.2 | 4 | +7 |

| MACS1-spln | B | Dual tropic | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 2.4 ± 1.0 | 2 | +7 |

| Ba-L | B | R5 | 4.3 ± 0.8 | 132 ± 92 | 31 | +4 |

| 92RW016 | A | R5 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | >1,000f | >431 | +5 |

| NB25e | B | R5 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 270f | 159 | +8 |

X4 denotes HIV-1 that uses the CXCR4 chemokine receptor for entry, R5 denotes HIV-1 that uses the CCR5 chemokine receptor for entry and dual tropic can use both X4 and R5 receptors for entry.

50% effective concentration (EC50) ± standard error was determined in the TZM-bl indicator cell line from at least three independent assays. Data was obtained from (Tyssen et al., 2010).

50% virucidal concentration (VC50) ± standard error was determined in the HLA-DR capture assay using the TZM-bl indicator cell line from at least three independent assays (except for 92RW016 and NB25).

VC50 divided by the EC50.

Early R5 HIV-1 isolated from PBMC of an individual that was asymptomatic with CD4 counts >500 cells/µl (CDC category II disease)(Tyssen et al., 2010).

Data from two independent assays.

Molecular modeling predicts that SPL7013 binds to the HIV-1 gp120 V3 loop, in addition to conserved positively charged residues in the CD4 induced domain on gp120 (Tyssen et al., 2010). The greater virucidal activity against X4 compared to R5 HIV-1 strains suggests that the interaction of SPL7013 with HIV-1 is in part mediated by electrostatic interactions with positively charged residues in the V3 loop of X4 HIV-1. To determine whether SPL7013 virucidal activity correlates with the overall charge on the V3 loop we manually calculated the net charge by identifying positively charged residues (His, Arg, Lys) and negatively charged amino acids (Asp, Glu) in the protein sequences (Pinter, 2007). While there was a trend where X4 and R5X4 HIV-1 strains with a higher V3 loop charge tended to be more susceptible to SPL7013 virucidal activity, this measure did not appear to be the sole determinant (Table 1). For example, the R5X4 strain MACS1-spln does not have the highest positive charge (+7) although it is the most sensitive to SPL7013 virucidal activity while the clade D strain (+8) and NB25 (+8) have a higher charge than MACS1-spln but are less susceptible to inactivation by SPL7013. The lack of association between overall V3 loop charge and SPL7013 virucidal potency suggests additional factors mediate virucidal susceptibility to the dendrimer. In this regard it is possible that the positive charges associated with V3 loops differ in their accessibility to the dendrimers due to the conformational property of the V3 loops (Sterjovski et al., 2010) or modifications in the N-linked glycosylation sites around the base of the V3 loops. For example, the MACS1-spln sequence lacks two clade B consensus N-linked glycosylation sites located upstream and downstream of the V3 loop.

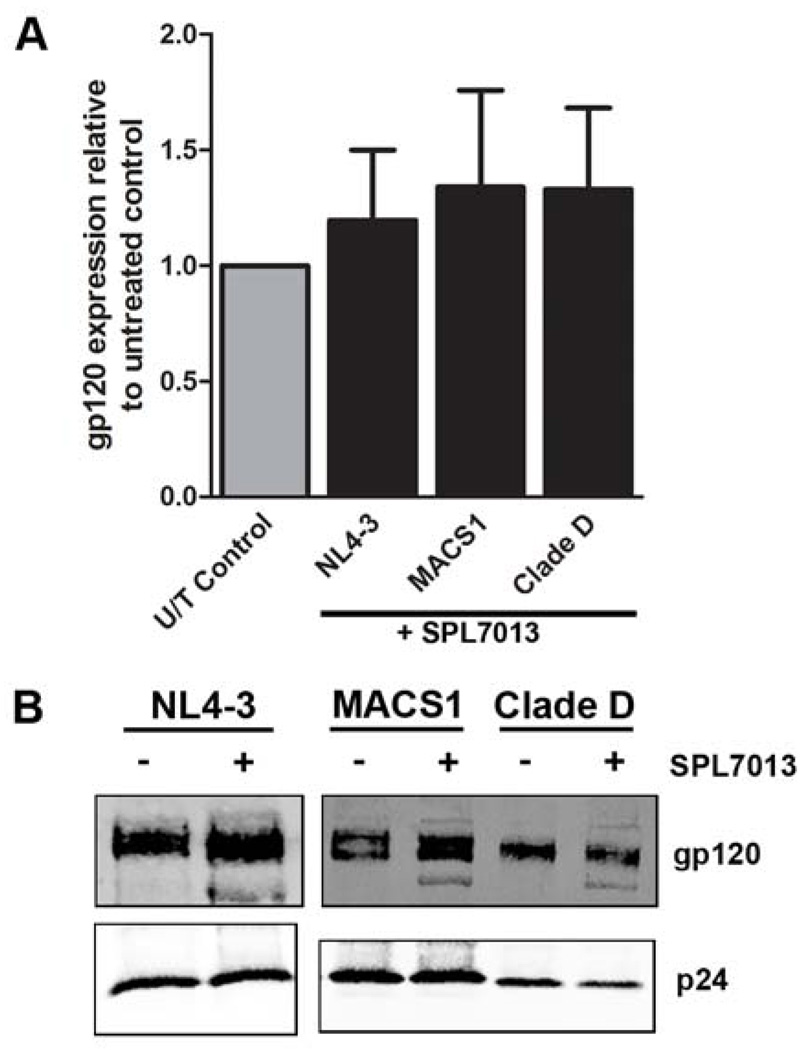

We next determined whether SPL7013 virucidal activity was due to either disruption of the viral particle or loss of the gp120 surface protein, which is essential for viral attachment to the host cell. Accordingly, we treated NL4.3, 92UG046 and MACS1-spln with SPL7013 followed by ultracentrifugation and quantitative Western blot analysis (Figueiredo et al., 2006). Our results show that SPL7013 does not disrupt HIV-1 as determined by the presence of p24 capsid following pelleting through a sucrose cushion (Figure 2). In addition, there was no significant decrease in gp120 on the surface of the virion compared to the corresponding untreated virus (Figure 2). We consistently observed a faster migrating band running immediately below gp120 in SPL7013 treated but not in untreated HIV-1 (Figure 2B). This band may represent gp120 that has lost carbohydrate from the surface. However, taken together with the complete inactivation of HIV-1 NL4.3 by SPL7013 at 200 µg/ml used in the assay (Figure 1) and the relative low abundance of this species compared to fully glycosylated gp120 (Figure 2B), it is unlikely that this minor species would play a major role in SPL7013 virucidal activity.

Figure 2. SPL7013 treated HIV-1 does not lead to viral disruption or loss of gp120 surface protein.

(A). Quantitation of the expression of gp120 relative to p24 in SPL7013 treated virus normalized to untreated HIV-1 (U/T Control). Virus was treated with 200 µg/ml of SPL7013 for 1 h at 37°C followed by ultracentrifugation at 120,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C through a 25% (w/v) sucrose cushion. The pellets were resuspended in TNEN buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA and 0.5% IGEPAL) containing protease inhibitors (1 µg/ml each of aprotinin, leupeptin and pepstatin), subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by quantitative Western blot analysis using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System as described previously (Figueiredo et al., 2006). Human anti-p24 from pooled sera was used to detect HIV capsid, mouse anti-gp120 ID6 was used to detect NL4.3 gp120 and sheep anti-gp120 (Shutt et al., 1998) was used to detect gp120 of MACS1-spln and the clade D strain. Secondary antibodies used were IRDye 800CW conjugated affinity purified anti-human IgG (Rockland), Alexa Fluor 680 Goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) and Alex Fluor 680 donkey anti-sheep IgG (Invitrogen). The gp120 expression was normalized for p24 expression then expressed as a ratio to the gp120:p24 normalised value for the untreated control, which was set to 1.0. Data were derived from four independent assays for NL4.3 and the clade D strain (92UG046) and three independent assays for MACS1 (MACS1-spln). No significant difference was observed for the gp120:p24 ratio for SPL7013 treated compared to untreated NL4.3 (p=0.44, n=4), clade D (p=0.56, n=4) and MACS1-spln (p=0.35, n=3) using the Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test. Error bars denote standard error of the mean. (B). Representative Western blot of untreated (−) and SPL7013 treated (+) virus showing gp120 and p24 viral proteins.

We have established that SPL7013 mediates its virucidal activity against X4 HIV-1 strains by a mechanism that does not involve disruption of the viral particle or loss of gp120 from the viral surface. Other virucidal mechanisms may include either tight binding of SPL7013 to HIV-1 envelope proteins, thus physically blocking binding of the virus to the host cell receptors, or by interactions with viral envelope proteins that lead to envelope conformational changes that abrogate viral infectivity. The formation of a dead-end gp41 six-helix bundle has been described as a HIV-1 virucidal mechanism for the anionic polymers cellulose acetate phthalate (CAP) and PRO 2000, which involves the stripping of envelope surface protein (Fletcher and Shattock, 2008; Neurath et al., 2002a; Neurath et al., 2002b). However, dead-end gp41 six-helix bundle formation induced by CAP, but not PRO 2000, was associated with disintegration of viral particles indicating different mechanisms of viral inactivation (Neurath et al., 2002b).

Combined with the observation that SPL7013 demonstrates similar EC50 values for both X4 and R5 HIV-1 in cell culture assays (Tyssen et al., 2010) the differential virucidal activity seen in the current study indicates that inhibition of each of these viruses may be due to a similar or a distinct mechanism. For X4 strains the main mechanism appears to be direct virucidal activity via irreversible binding (tighter binding) to HIV-1 envelope proteins, although potent virucidal activity may not be observed for all X4 strains. In contrast, inhibition of R5 strains by SPL7013 may be due to reversible binding (i.e. weaker binding) to HIV-1 envelope proteins (that does not lead to direct HIV-1 inactivation). Inhibition of R5 strains may also be mediated through binding of the dendrimer to the host cell CD4 and chemokine receptors. In this regard, previous studies with PRO 2000, a synthetic linear polyanion of ~5kDa comprising naphthlalene monosulfonic acid residues, report that it binds to CD4 and CXCR4 in addition to HIV-1 gp120 (Huskens et al., 2009; Rusconi et al., 1996; Scordi-Bello et al., 2005). While dendrimers have a flexible globular structure, the surface groups are similar, although not identical to PRO 2000 suggesting that SPL7013 might also bind to host cell receptors as observed for PRO 2000.

We have demonstrated that SPL7013 has HIV-1 virucidal activity against X4 and R5X4 but not R5 HIV-1 strains. VivaGel® contains 30 mg/ml of SPL7013 which is 450–12,500-fold greater than the VC50 values for X4 and R5X4 strains, 230-fold greater than that for the R5 strain Ba-L and >30-fold greater for the primary 92RW016 R5 isolate. Nevertheless, in the absence of potent R5 virucidal activity, the ability of a microbicide to colocalize with HIV-1 at target cells in the lower epithelial layers and submucosa becomes more critical in the context of preventing the sexual transmission of HIV-1. Studies to understand the precise interactions between SPL7013 and HIV-1 target proteins mediating viral inactivation could potentially lead to the design of new dendrimers that inactivate all HIV-1 strains.

Acknowledgements

Funding

We thank the NIH AIDS Research & Reference Reagent Program Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH and The UNAIDS Network for HIV Isolation and Characterization for providing HIV-1 isolates 92UG046 and 92RW016 used in this study. TZM-bl cells were obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, contributed by Dr John C. Kappes, Dr. Xiaoyun Wu and Tranzyme Inc. We thank Dana Gabuzda for providing the MACS1-spln isolate, Anthony L Cunningham for providing HIV-1 patient isolate NB25, Dale McPhee for providing the human p24 antibody and HIV-1 strain MBC200, and Andy Poumbourios for providing the gp120 antibody, 567. We also thank Al Profy for providing PRO 2000. This study was supported by US Federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services Grant No. U19 AI060598 and Contract No. HHSN266200500042C awarded to Starpharma Pty Ltd. GT was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia Senior Research Fellowship 543105 and funding from the Australian Centre for HIV and Hepatitis Virology Research (ACH2). JS was supported by ACH2 funding. PRG was supported by an NHMRC Level 2 Biomedical Career Development Award and PAR was supported by an NHMRC R Douglas Wright Career Development Award 365209. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution to this work of the Victorian Operational Infrastructure Support Program received by the Burnet Institute. The funding agencies had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. All results and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of NIH.

List of abbreviations

- X4

CXCR4-using

- R5

CCR5-using

- EC50

50% effective concentration

- VC50

50% virucidal concentration

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing interests

GT has received funding from Starpharma Pty Ltd for contract work and consultancy. GRL and JRAP are employees of Starpharma Pty Ltd. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Sushama Telwatte, Email: sushama.t@burnet.edu.au.

Katie Moore, Email: katie.moore@burnet.edu.au.

Adam Johnson, Email: adamj@burnet.edu.au.

David Tyssen, Email: davidt@burnet.edu.au.

Jasminka Sterjovski, Email: jasminka@burnet.edu.au.

Muriel Aldunate, Email: muriel@burnet.edu.au.

Paul R Gorry, Email: gorry@burnet.edu.au.

Paul A Ramsland, Email: pramsland@burnet.edu.au.

Gareth R Lewis, Email: gareth.lewis@starpharma.com.

Jeremy R A Paull, Email: jeremy.paull@starpharma.com.

Secondo Sonza, Email: sonza@burnet.edu.au.

References

- Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Frohlich JA, Grobler AC, Baxter C, Mansoor LE, Kharsany AB, Sibeko S, Mlisana KP, Omar Z, Gengiah TN, Maarschalk S, Arulappan N, Mlotshwa M, Morris L, Taylor D. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science. 2010;329:1168–1174. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abner SR, Guenthner PC, Guarner J, Hancock KA, Cummins JE, Jr, Fink A, Gilmore GT, Staley C, Ward A, Ali O, Binderow S, Cohen S, Grohskopf LA, Paxton L, Hart CE, Dezzutti CS. A human colorectal explant culture to evaluate topical microbicides for the prevention of HIV infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2005;192:1545–1556. doi: 10.1086/462424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzarini J, Van Damme L. Microbicide drug candidates to prevent HIV infection. Lancet. 2007;369:787–797. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DI, Stanberry LR, Sacks S, Ayisi NK, Gong YH, Ireland J, Mumper RJ, Holan G, Matthews B, McCarthy T, Bourne N. Evaluations of unformulated and formulated dendrimer-based microbicide candidates in mouse and guinea pig models of genital herpes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3784–3788. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.12.3784-3788.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JM, Wald A, Hubbard A, Rungruengthanakit K, Chipato T, Rugpao S, Mmiro F, Celentano DD, Salata RS, Morrison CS, Richardson BA, Padian NS. Incident and prevalent herpes simplex virus type 2 infection increases risk of HIV acquisition among women in Uganda and Zimbabwe. AIDS. 2007;21:1515–1523. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282004929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MY, Millwood IY, Wand H, Poynten M, Law M, Kaldor JM, Wesselingh S, Price CF, Clark LJ, Paull JR, Fairley CK. A randomized controlled trial of the safety of candidate microbicide SPL7013 gel when applied to the penis. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2009;50:375–380. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318198a7e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins JE, Jr, Guarner J, Flowers L, Guenthner PC, Bartlett J, Morken T, Grohskopf LA, Paxton L, Dezzutti CS. Preclinical testing of candidate topical microbicides for anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 activity and tissue toxicity in a human cervical explant culture. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007;51:1770–1779. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01129-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dezzutti CS, James VN, Ramos A, Sullivan ST, Siddig A, Bush TJ, Grohskopf LA, Paxton L, Subbarao S, Hart CE. In vitro comparison of topical microbicides for prevention of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmission. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3834–3844. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.10.3834-3844.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo A, Moore KL, Mak J, Sluis-Cremer N, de Bethune MP, Tachedjian G. Potent nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors target HIV-1 Gag-Pol. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e119. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PS, Shattock RJ. PRO-2000, an antimicrobial gel for the potential prevention of HIV infection. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2008;9:189–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PS, Wallace GS, Mesquita PM, Shattock RJ. Candidate polyanion microbicides inhibit HIV-1 infection and dissemination pathways in human cervical explants. Retrovirology. 2006;3:46. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman EE, Weiss HA, Glynn JR, Cross PL, Whitworth JA, Hayes RJ. Herpes simplex virus 2 infection increases HIV acquisition in men and women: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. AIDS. 2006;20:73–83. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000198081.09337.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong E, Matthews B, McCarthy T, Chu J, Holan G, Raff J, Sacks S. Evaluation of dendrimer SPL7013, a lead microbicide candidate against herpes simplex viruses. Antiviral Res. 2005;68:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorry PR, Bristol G, Zack JA, Ritola K, Swanstrom R, Birch CJ, Bell JE, Bannert N, Crawford K, Wang H, Schols D, De Clercq E, Kunstman K, Wolinsky SM, Gabuzda D. Macrophage tropism of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates from brain and lymphoid tissues predicts neurotropism independent of coreceptor specificity. J. Virol. 2001;75:10073–10089. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.21.10073-10089.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huskens D, Vermeire K, Profy AT, Schols D. The candidate sulfonated microbicide, PRO 2000, has potential multiple mechanisms of action against HIV-1. Antiviral Res. 2009;84:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang YH, Emau P, Cairns JS, Flanary L, Morton WR, McCarthy TD, Tsai CC. SPL7013 gel as a topical microbicide for prevention of vaginal transmission of SHIV89.6P in macaques. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2005;21:207–213. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackman-Smith C, Osterling C, Luckenbaugh K, Mankowski M, Snyder B, Lewis G, Paull J, Profy A, Ptak RG, Buckheit RW, Jr, Watson KM, Cummins JE, Jr, Sanders-Beer BE. Development of a comprehensive human immunodeficiency virus type 1 screening algorithm for discovery and preclinical testing of topical microbicides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1768–1781. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01328-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neurath AR, Strick N, Jiang S, Li YY, Debnath AK. Anti-HIV-1 activity of cellulose acetate phthalate: synergy with soluble CD4 and induction of "dead-end" gp41 six-helix bundles. BMC Infect. Dis. 2002a;2:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neurath AR, Strick N, Li YY. Anti-HIV-1 activity of anionic polymers: a comparative study of candidate microbicides. BMC Infect. Dis. 2002b;2:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-2-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Loughlin J, Millwood IY, McDonald HM, Price CF, Kaldor JM, Paull JR. Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of SPL7013 Gel (VivaGel(R)): A Dose Ranging, Phase I Study. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2010;37:100–104. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181bc0aac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelrichs RB, Lawson VA, Coates KM, Chatfield C, Deacon NJ, McPhee DA. Rapid full-length genomic sequencing of two cytopathically heterogeneous Australian primary HIV-1 isolates. J Biomed. Sci. 2000;7:128–135. doi: 10.1007/BF02256619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton DL, Cosgrove Sweeney YT, McCarthy TD, Hillier SL. Preclinical safety and efficacy assessments of dendrimer-based (SPL7013) microbicide gel formulations in a nonhuman primate model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1696–1700. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.5.1696-1700.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinter A. Roles of HIV-1 Env variable regions in viral neutralization and vaccine development. Curr. HIV Res. 2007;5:542–553. doi: 10.2174/157016207782418470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupp R, Rosenthal SL, Stanberry LR. VivaGel (SPL7013 Gel): a candidate dendrimer--microbicide for the prevention of HIV and HSV infection. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2007;2:561–566. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusconi S, Moonis M, Merrill DP, Pallai PV, Neidhardt EA, Singh SK, Willis KJ, Osburne MS, Profy AT, Jenson JC, Hirsch MS. Naphthalene sulfonate polymers with CD4-blocking and anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 activities. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1996;40:234–236. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.1.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scordi-Bello IA, Mosoian A, He C, Chen Y, Cheng Y, Jarvis GA, Keller MJ, Hogarty K, Waller DP, Profy AT, Herold BC, Klotman ME. Candidate sulfonated and sulfated topical microbicides: comparison of anti-human immunodeficiency virus activities and mechanisms of action. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005;49:3607–3615. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.9.3607-3615.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shutt DC, Jenkins LM, Carolan EJ, Stapleton J, Daniels KJ, Kennedy RC, Soll DR. T cell syncytia induced by HIV release. T cell chemoattractants: demonstration with a newly developed single cell chemotaxis chamber. J. Cell. Sci. 1998;111:99–109. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonza S, Johnson A, Tyssen D, Spelman T, Lewis GR, Paull JR, Tachedjian G. Enhancement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication is not intrinsic to all polyanion-based microbicides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:3565–3568. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00102-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterjovski J, Roche M, Churchill MJ, Ellett A, Farrugia W, Gray LR, Cowley D, Poumbourios P, Lee B, Wesselingh SL, Cunningham AL, Ramsland PA, Gorry PR. An altered and more efficient mechanism of CCR5 engagement contributes to macrophage tropism of CCR5-using HIV-1 envelopes. Virology. 2010;404:269–278. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyssen D, Henderson SA, Johnson A, Sterjovski J, Moore K, La J, Zanin M, Sonza S, Karellas P, Giannis MP, Krippner G, Wesselingh S, McCarthy T, Gorry PR, Ramsland PA, Cone R, Paull JR, Lewis GR, Tachedjian G. Structure activity relationship of dendrimer microbicides with dual action antiviral activity. PloS ONE. 2010;5:e12309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Report on the global AIDS epidemic. 2008 [Google Scholar]