Abstract

The escalating problem of multiple chronic conditions (MCC) among Americans is now a major public health and medical challenge, associated with suboptimal health outcomes and rising health-care expenses. Despite this problem's growth, the delivery of health services has continued to employ outmoded “siloed” approaches that focus on individual chronic diseases. We describe an action-oriented framework—developed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services with additional input provided by stakeholder organizations—that outlines national strategies for maximizing care coordination and for improving health and quality of life for individuals with MCC. We note how the framework's potential can be optimized through some of the provisions of the new Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, and through public-private partnerships.

The problem of multiple (≥2) chronic conditions (MCC) among Americans has rapidly escalated to become a major public health and medical challenge.1,2 The combined effects of increasing life expectancy and the aging of the population undoubtedly will further increase the associated societal burden of chronic illnesses among future populations of older people. These chronic illnesses—defined as “conditions that last a year or more and require ongoing medical attention and/or limit activities of daily living”3,4—include a broad array of physical illnesses, such as arthritis, asthma, chronic respiratory conditions, diabetes and its complications, heart disease, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and hypertension. Also included are the panoply of behavioral conditions, such as substance use and addiction disorders, mental illnesses, dementia and other cognitive impairment disorders, and developmental disabilities.

Because people with MCC suffer suboptimal health outcomes and incur rising health-care expenses, enhanced attention on this population is critical to improve health-care quality and costs. Yet, the current delivery of community health and health services has continued to focus on increasingly outmoded and siloed perspectives that concentrate on individual chronic diseases. To date, no one has attempted to offer an action-oriented framework that outlines national strategies to maximize care coordination and improve health and quality of life for individuals with MCC.

In this article, we offer such a framework, developed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) with additional input provided by stakeholder organizations. We also note how the framework's potential can be optimized through some of the new provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA). We conclude with suggestions on future applications of this framework through public-private partnerships.

MCC: MAGNITUDE AND SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

More than one in four Americans have multiple, concurrent chronic conditions5 that are associated with myriad etiologies. The prevalence of MCC among individuals increases with age, with some estimates including as many as two-thirds of older adults affected.6,7 The number of chronic conditions in an individual is directly related to risks of adverse outcomes ranging from mortality, poor functional status, unnecessary hospitalizations, adverse drug events, and duplicative tests, to conflicting medical advice.3,8–10 Complicating this picture is that some combinations of conditions, or clusters, have synergistic interactions.10 One important cluster deserving of special attention is the co-occurrence of physical and behavioral conditions, such as depression.11

The resource implications for addressing MCC are immense: 66% of total health-care spending is directed toward care for the approximately 27% of Americans with MCC.5 Chronic disease among Medicare beneficiaries is a key factor driving the overall increased growth in spending in the traditional Medicare program.12 Moreover, individuals with MCC have faced substantial challenges related to out-of-pocket costs of their care, including higher costs for prescription drugs.5

Deficiencies in care coordination represent a particularly vexing problem, as underscored by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) in its 2001 report, Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. The report noted that patients actively receiving care for one chronic condition may not necessarily receive care for another, unrelated condition. The IOM warned against designing care around specific conditions to avoid defining patients solely by a single disease or condition.13,14 Moreover, disease-specific instruction also may be less important than problem-solving skills, as many of the challenges inherent in living with a chronic condition are common across many chronic diseases and involve day-to-day problem solving. Such challenges include management of emotions (e.g., discouragement, fear, and depression); medication use and side effects; adherence to diet and physical activity regimes; and communication with health-care providers.15

Several conceptual models have been produced that attempt to transcend the focus on individual disease management and move toward broader approaches to managing chronic illness. Among the most influential is the Chronic Care Model, which elucidates the elements required to improve chronic illness care, including systems requirements for health-care organization, community resources, self-management support, delivery design, decision support, and clinical information.16 This seminal model promotes more productive interactions between the patient and care team, and also represents a conceptual foundation for innovative approaches to addressing MCC. Expanded versions of this model have been developed to take into account the social determinants of health, as well as different levels of the health-care system.17,18

Focused initiatives have yielded insights into select aspects of the Chronic Care Model, one of which is chronic disease self-management. For example, the Stanford Chronic Disease Self-Management Program is a community-based self-management program that helps people with chronic illness gain self-confidence in their ability to control their symptoms and manage how their health problems will affect their lives.19,20 More recently, a research synthesis report supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation identified the characteristics of successful care management programs,21 and a report commissioned by the National Coalition on Care Coordination detailed those models that decrease hospitalization and improve outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries with chronic illness.22 All of these efforts have been instrumental in highlighting the need to move to a more effective, encompassing approach to address chronic conditions.

What has been lacking is (1) the explicit recognition of the emergence of MCC as an additional, important level of complexity, and (2) a framework that builds on elements identified in these models and converts them into a set of specific, actionable, national-level strategies. Such a framework would allow for identification of gaps in achieving improved care for MCC and also opportunities for collaboration between the public and private sectors.

A STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK FOR GUIDING EFFORTS TO MITIGATE MCC

HHS administers a large number of federal programs directed toward the prevention and management of chronic conditions, including financing health-care services; delivering care and services to people with chronic conditions; conducting basic, interventional, and systems research; implementing programs to prevent and manage chronic disease; and overseeing development of safe and effective drug therapies for chronic conditions. These national-level roles position HHS to offer new directions in improving health outcomes in individuals with MCC.

To identify options for improving the health of this heterogeneous population, HHS convened a departmental workgroup on individuals with MCC. The workgroup's priorities were to (1) create an inventory of existing HHS programs, activities, and initiatives focused on improving the health of individuals with MCC; and (2) develop a strategic framework that provides a roadmap for improving the health status of people with MCC.23 The framework would supply principles for future planning and action. The workgroup included high-level representatives from each agency within HHS as well as its staff divisions. Also, to actively engage communities and other stakeholders, the draft framework was announced in the Federal Register in May 2010 with a request for feedback. Comments from approximately 250 stakeholder organizations and others helped shape the final version of the strategic framework.

Framework goals for addressing MCC

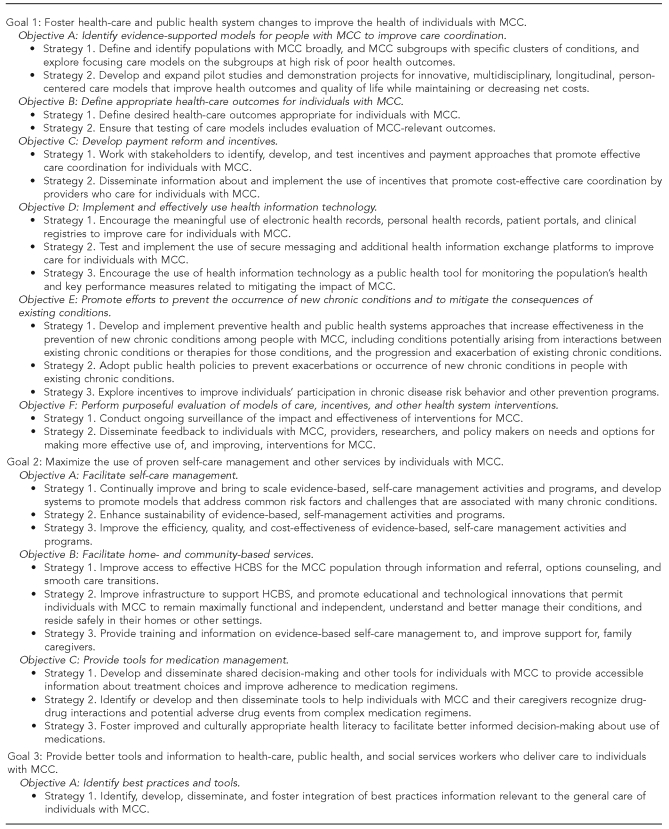

As part of the strategic framework, the workgroup articulated the following vision: “optimum health and quality of life for individuals with multiple chronic conditions.” Within this vision are four interdependent goals: (1) foster health-care and public health system changes to improve the health of individuals with MCC; (2) maximize the use of proven self-care management and other services by individuals with MCC; (3) provide better tools and information to health-care, public health, and social services workers who deliver care to individuals with MCC; and (4) facilitate research to fill knowledge gaps about, and interventions and systems to benefit, individuals with MCC. Each of these goals includes key objectives and strategies that HHS, in conjunction with stakeholders, can use to guide efforts addressing MCC (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

HHS strategic framework on multiple chronic conditions, including goals, objectives, and abridged strategiesa

aFor full text, see: Department of Health and Human Services (US). HHS initiative on multiple chronic conditions [cited 2011 Mar 22]. Available from: URL: http://www.hhs.gov/ash/initiatives/mcc/index.html

HHS = Department of Health and Human Services

MCC = multiple chronic conditions

HCBS = Home- and Community-Based Services

HRSA = Health Resources and Services Administration

Goal 1: Foster health-care and public health system changes to improve the health of individuals with MCC.

Individuals with MCC require heightened care coordination. Yet, the current model of fee-for-service medical care offers few financial incentives to do so, with the current system involving numerous uncoordinated independent providers and subscribers. In addition, traditional disease management programs, without a strong link to primary care and focused on singular or discrete conditions, have not been optimally effective.24,25 Goal 1 strengthens the health-care and public health systems to improve access and medical care coordination.

Achieving this goal necessitates changing the delivery and provider payment systems through strategies captured by six objectives (A–F). Objective A, which calls for the identification of evidence-supported care management models, recognizes the recent emergence of several new ones that emphasize patient-centered multidisciplinary care, provider communication and cooperation to smooth transitions across settings, and incorporation of public health and community resources. Examples include patient-centered medical homes, community health teams, accountable care organizations, behavioral health models, palliative care, and home health services.22,26–28

Objective B defines appropriate health-care outcomes for individuals with MCC, centering on maintenance of function, palliation of symptoms, prevention of adverse drug events, avoidance of unnecessary emergency department visits, and reduced hospitalizations and re-hospitalizations. These outcomes have heightened importance for MCC populations that shoulder the burden of an increased risk of negative outcomes (e.g., an increasing number of chronic conditions in an individual raises the risk of re-hospitalization).29

Objective C—developing payment reform and incentives—recognizes the need for provider incentives for care coordination, especially as limitations on reimbursement for many non-physician providers constrain multidisciplinary care delivery. Encouraging use of care models through financial incentives would support providers who need additional time to address the care complexities for this population.

Objective D emphasizes the roles of interoperable health information technology in facilitating coordinated care and providing uniform information for providers. One important strategy will be to encourage the meaningful use of electronic health records, personal health records, patient portals, and clinical registries.

Objective E focuses on preventing new chronic conditions through modifications to the health and public health systems, adoption of public policies, and exploration of incentives for individuals to participate in prevention programs.

The final objective highlights the need for evaluation of models of care and other health system interventions.

Goal 2: Maximize the use of proven self-care management and other services by individuals with MCC.

Providing the highest quality of care to individuals will alone not guarantee improved health outcomes for this population. In addition, individuals with MCC must be informed, motivated, and committed to being partners in their own care.30 Reaching this goal may be challenging as many individuals with MCC (e.g., those with severe illness or substantial cognitive decline) may be limited in their ability to perform self-care. Therefore, the important roles played by families and other caregivers in the management of chronic conditions must be recognized and supported. To maximize the involvement of individuals and their caregivers, Goal 2 focuses on facilitating self-care management, as well has home- and community-based services, and on developing and providing tools for medication management.

Goal 2 comprises three objectives. Objective A addresses the imperative for translating and replicating the significant evidence base generated by chronic disease self-care management programs.31,32 Applying these programs in multiple settings (e.g., health care, the home, work, assisted living, and others) can improve the health status of those with MCC. Objective B focuses on actions to facilitate evidence-based home- and community-based services to support individuals in their daily activities. Examples include those programs that retrain Medicaid home health aides to provide appropriate home-based physical activity, prevent falls, and provide peer support to reduce the severity of depressive symptoms. The final objective identifies strategies related to tools for medication management. As the number of chronic conditions increases, so do the number of medications prescribed, as well as the degree of nonadherence to regimens.33 Reminders and patient education to improve knowledgeable use of medications can reduce adverse drug events and medication errors, and may reduce chronic disease progression. These needs underscore the requirement for developing and disseminating information about important medication considerations (e.g., treatment choices, drug-drug interactions and adverse events, and improving adherence to medication regimens) to individuals with MCC and their caregivers.

Goal 3: Provide better tools and information to health-care, public health, and social services workers who deliver care to individuals with MCC.

Health-care, public health, and social services professionals provide care for individuals with MCC in an environment that substantially lacks relevant data for this population. Through three objectives, Goal 3 recognizes the critical need for providing relevant data to these professionals, as well as to family caregivers.

Objective A centers on identifying best practices and tools to promote a systematic approach to the assessment and management of this complex population, including the prevention of additional comorbidities. Another important example is the need for improved medication management with associated reductions in prescriptions of inappropriate medications and patient risks associated with polypharmacy.

Some evidence suggests that many health-care professional trainees feel uncomfortable with key chronic care competencies.34 Hence, Objective B covers approaches for strengthening training, improving providers' cultural competencies, and ensuring that providers are proficient in interacting with family caregivers. Objective C addresses the importance of incorporating MCC into clinical guidelines and the need for more evidence-based, person-centered clinical MCC guidelines to assist health-care providers in providing high quality care. Current guidelines on specific chronic conditions often do not take into account the presence of MCC and how these comorbidities may affect the treatment plan.35 Moreover, guidelines for people with mental illness and substance abuse rarely address the co-occurrence of other chronic conditions.

Goal 4: Facilitate research to fill knowledge gaps about, and interventions and systems to benefit, individuals with MCC.

Efforts to improve the health and quality of life for individuals with MCC are severely constrained by gaps in foundational research. Examples include aspects of basic investigation of medical therapies for people with MCC; epidemiologic study of the impact of different types of comorbidities on disease trajectories; the efficacy, effectiveness, and comparative effectiveness of trials of promising interventions for health promotion and self-management; and assessment of the impact of health system care management strategies. Bolstering research efforts will enable improved characterization of the population with MCC, support health-care and other providers in coordinating and managing care for this population, and assist in tracking progress in improving health.36 To address these gaps, the objectives for Goal 4 encompass important issues concerning clinical trials, community, and patient-centered research; the epidemiology of MCC; and the roles of disparities among the population of individuals with MCC.

Increasing the external validity (i.e., the degree to which study results generalize to populations and contexts beyond the particular ones included in the studies themselves)37 of relevant clinical trials is the focus of the first objective. As the number of individuals with MCC continues to grow, treatment interventions (e.g., drugs, devices, lifestyle modifications, and alternative medicine) for these conditions must be safe and effective. To this end, better understanding of interactions between comorbidities and limiting exclusions of this increasingly large population from clinical trials may assist in preventing adverse events and poor outcomes. Objective B acknowledges the significant evidence base limitations in fully understanding the most prevalent constellations of conditions and disabilities that comprise MCC. Accordingly, this objective emphasizes the need for additional research—including the use of existing program (e.g., Medicare) and other datasets—to identify the most common patterns of MCC as an essential means to target future specific interventions.

Elucidation of the evidence base can advance the prevention, management, and treatment of individuals with MCC. Objective C, therefore, emphasizes the needs for research to enable clinicians to direct care toward outcomes of highest importance to individuals with MCC, including information on current policies that create disincentives for providers to adequately address the needs of such individuals. Feedback on research progress should be provided to the public and to key groups, including individuals, providers, researchers, and policy makers. Finally, because of numerous disparities that characterize the MCC population (e.g., disparities involving race/ethnicity, gender, gender identity, disability, sexual orientation, age, geographic location, access to care, and health outcomes), Objective D highlights the need to address disparities, and the differences in risk and interventions, across subgroups of people with MCC.

MULTIPLE CHRONIC CONDITIONS AND THE PPACA

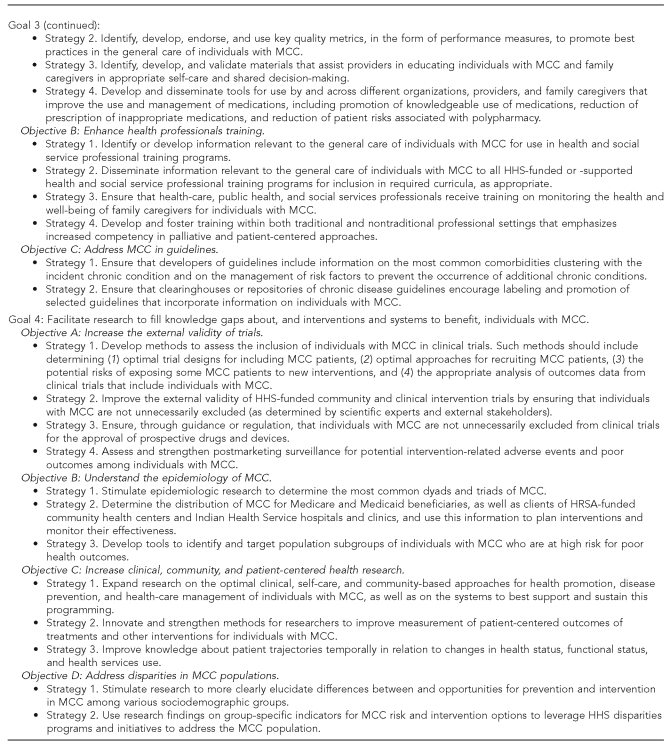

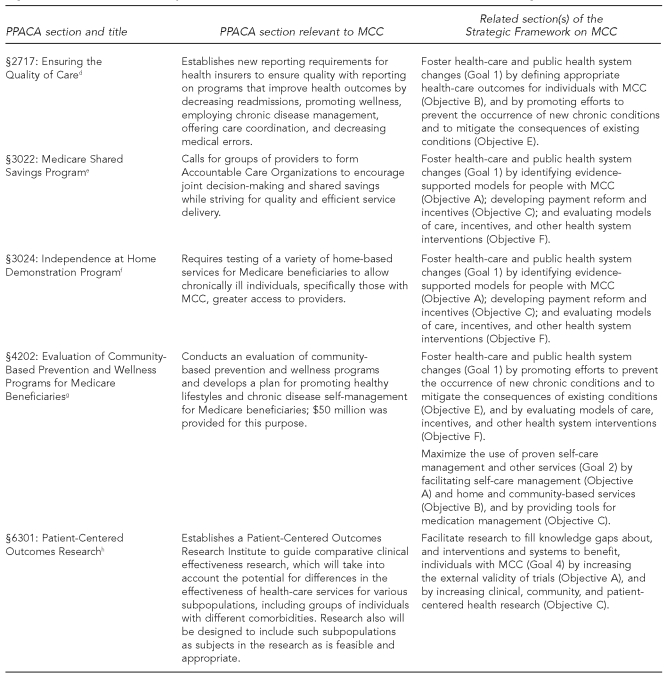

Several provisions of the new health reform law (the PPACA38) provide powerful opportunities for addressing MCC. Many PPACA provisions directly relate to elements of the HHS Strategic Framework, especially Goal 1 with its emphasis on strengthening the health-care and public health systems. These provisions have the potential to help significantly advance the Framework's aims.

Figure 2 captures some selected provisions that could create a foundation for addressing MCC through the development and testing of new approaches to coordinated care and management, patient-centered benefits, and quality measures. For example, Section 3021 (Establishment of Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation)39 encourages development of new payment and service delivery models, and thereby aligns with aims of the Framework's Goal 1 to foster pertinent health-care system changes. Additional provisions support the development of specific care management models including, for example, health homes and accountable care organizations, and home-based services. Section 2703 (State Option to Provide Health Homes for Enrollees with Chronic Conditions)40 presents states with the option to receive planning grants to design health homes for testing of care management models for Medicaid enrollees with MCC.

Figure 2.

Selected provisions of the PPACA related to elements of the HHS Strategic Framework on MCC

aPublic Law 111-148, §2703.

bPublic Law 111-148, §3026.

cPublic Law 111-148, §3021.

dPublic Law 111-148, §2717.

ePublic Law 111-148, §3022.

fPublic Law 111-148, §3024.

gPublic Law 111-148, §4202.

hPublic Law 111-148, §6301.

PPACA = Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

HHS = Department of Health and Human Services

MCC = multiple chronic conditions

Section 3022 (Medicare Shared Savings Program)41 addresses the roles for accountable care organizations, defined as a set of collaborating providers that accept joint responsibility for the quality and cost of health care for a panel of patients (e.g., Medicare beneficiaries).42–44 Specifically, this provision calls for groups of providers to coordinate care for 5,000 or more Medicare beneficiaries and to share any appreciated savings resulting from reductions in hospitalizations. Section 3024 (Independence at Home Demonstration Program)45 requires the development and testing of a payment and service delivery model that uses physician and nurse practitioner/physician assistant home-based primary care; this model is directed toward Medicare beneficiaries with MCC. All of these provisions align with several objectives contained within the Framework's Goal 1 for health-care system changes.

Also inherent to Goal 1 is the necessity to define appropriate health-care outcomes for individuals with MCC. Avoiding hospital readmissions, an outcome with an occurrence that is proportionate to the number of chronic conditions in an individual,29 is a focus of Section 3026 (Community-Based Care Transitions Program).46 This provision allocates funding to pilot community-based transition programs that would devise interventions (e.g., comprehensive medication review or more timely follow-up clinic visits) to minimize fragmented care between hospital discharges and outpatient treatment for high-risk Medicare beneficiaries, including those with MCC.

A final provision supportive of the Framework's Goal 1 is Section 2717 (Ensuring the Quality of Care).47 Among other requirements, this provision addresses the improvement of health outcomes through the implementation of effective case management and care coordination, including the use of medical homes. It also stresses the importance of reducing hospital readmissions. These measures hold the potential for creating incentives for better care of those with MCC.

PPACA also supports the implementation of strategies contained in the other goals of the HHS Strategic Framework. For example, Goal 2 emphasizes maximizing the use of proven self-care management and other services by facilitating self-care management. Section 4202 (Evaluation of Community-Based Prevention and Wellness Programs for Medicare Beneficiaries)48 appropriates funds for an evaluation of community-based prevention and wellness programs and calls for the development of a plan for promoting healthy lifestyles and chronic disease self-management for Medicare beneficiaries.

Goal 4 facilitates research to fill knowledge gaps about individuals with MCC, particularly by increasing clinical, community, and patient-centered health research. Section 6301 (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research)49 establishes an institute to guide comparative clinical effectiveness research, which will take into account the potential for differences in the effectiveness of health-care services for various subgroups, including groups of individuals with different comorbidities. Research also will be designed to include such subgroups as subjects as is feasible and appropriate.

DISCUSSION

Through its four distinct, but interdependent, fundamental goals, the HHS Strategic Framework on MCC helps to fill a major gap: it provides, for the first time, a cohesive model for strengthening coordination and effectiveness of efforts to improve health and quality of life for people with such conditions. It also builds on elements of the Chronic Care Model and converts them into specific, national-level strategies. Moreover, the PPACA can complement and accelerate the implementation of the Framework. In particular, the legislation provides opportunities to test and evaluate new approaches to MCC, and may help to lower the barriers to taking the most successful of these approaches to scale.

The Framework benefited from considerable input from external stakeholders, reflecting a strong commitment from both nongovernment as well as government sectors. The input reflected widespread agreement on several basic points, including the importance and urgency of addressing this issue, and the Framework's potential for helping to advance efforts to improve health and quality of life among individuals with MCC. The feedback also suggested the utility of strengthening collaboration between the private and public sectors in future efforts to develop implementation plans and additional strategies.

HHS will look to partnering organizations to help implement various Framework strategies. For example, as part of an existing contract with the Office of the HHS Assistant Secretary for Planning – Evaluation, the National Quality Forum (NQF) will undertake a project to develop and endorse a performance measurement model for patients with MCC.50 This model will establish the definitions, domains, and guiding principles that are instrumental for measuring and reporting the efficiency, quality, and cost of care for patients with MCC. The NQF effort is aligned with specific objectives in the MCC Framework to develop, endorse, and use key quality metrics to promote best practices in the care of individuals with MCC. Another potential area involves partnerships with professional societies to better address MCC in guidelines. Improved incorporation of relevant information, however limited, should enhance guidelines' applicability to an increasing number of individuals with MCC.

Considerations

While the Framework is the product of a deliberative and publicly vetted process, its use in addressing and solving the challenges posed by MCC nonetheless is subject to at least three additional considerations. First, the method for developing the Framework could not provide for the systematic collection of targeted input from those individuals who live with and experience MCC, nor from their caregivers. Second, even though the workgroup's membership comprised critically important, national-level subject-matter expertise, its representation drew exclusively from the federal government and did not include other sectors (e.g., nonfederal government, academia, and private sector providers). A final consideration involves issues of semantics and disease classification, and particularly the term “chronic.” For example, the workgroup examined the use of alternate terms, such as “multiple comorbidities” and “multiple persistent comorbidities,” but ultimately turned away from these terms because of recognition that the notion of multiple persistent disorders is less likely to be recognized in medicine than is “chronic conditions.”

CONCLUSIONS

All agree that MCC can overwhelm individuals, their families, and others who care for them; health-care professionals and other service providers; and our systems of care. The number of Americans with MCC will continue to increase as a function of the aging of the population, the continued existence of chronic disease risk factors, and the impact of modern medicine. We offer this Framework to help individuals with MCC, their families, health-care providers, health-care and public health systems, and communities to identify and implement approaches to optimizing health and quality of life, while also reducing the burdens of these conditions. Implementing the Framework will be a shared responsibility of the public and private sectors. Strengthening partnerships with and between these sectors will be critical to achieving the vision of “optimum health and quality of life for individuals with multiple chronic conditions.”

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jessica Trong and Lauren Brumsted for their specific contributions that assisted in enriching this article.

Footnotes

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Interagency Workgroup on Multiple Chronic Conditions includes: Charlene Avery, Mary Barton, Ursula Bauer, Sarah Bayko, Mary Beth Bigley, Ellen Blackwell, Wendy Braund, Peter Briss, Agnes Davidson, Paolo Delvecchio, David Dietz, Barbara Edwards, Bruce Finke, Steven Fong, James Galloway, Lori Gerhard, Kate Goodrich, Evan Hadley, Suzanne Haynes, Rebecca Hines, Peggy Honore, Elbert Huang, Lynn Hudson, Jeffrey Kelman, Sandra Kweder, Salma Lemtouni, Shari Ling, Sarah Linde-Feucht, Alefiyah Mesiwala, Karen Milgate, Mahak Nayyar, John Oswald, Susan Queen, Rochelle Rollins, James Sorace, Julie Taitsman, Robert Temple, Ken Thompson, Mimi Toomey, and Karen Weiss.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Association of Retired People Public Policy Institute. Chronic care: a call to action for health reform. 2009. [cited 2011 Mar 22]. Available from: URL: http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/health/beyond_50_hcr.pdf.

- 2.Schneider KM, O'Donnell BE, Dean D. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions in the United States' Medicare population. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:82. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warshaw G. Introduction: advances and challenges in care of older people with chronic illness. Generation. 2006;30:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hwang W, Weller W, Ireys H, Anderson G. Out-of-pocket medical spending for care of chronic conditions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:267–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson G. Chronic care: making the case for ongoing care. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation: Prince-ton (NJ); 2010. [cited 2011 Jan 19]. Also available from: URL: http://www.rwjf.org/files/research/50968chronic.care.chartbook.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson G, Horvath J. The growing burden of chronic disease in America. Public Health Rep. 2004;119:263–70. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paez KA, Zhao L, Hwang W. Rising out-of-pocket spending for chronic conditions: a ten-year trend. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:15–25. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.15. [published erratum appears in Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.15] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee TA, Shields AE, Vogeli C, Gibson TB, Woong-Sohn M, Marder WD, et al. Mortality rate in veterans with multiple chronic conditions. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 3):403–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0277-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogeli C, Shields AE, Lee TA, Gibson TB, Marder WD, Weiss KB, et al. Multiple chronic conditions: prevalence, health consequences, and implications for quality, care management, and costs. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 3):391–5. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0322-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G. Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2269–76. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370:851–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thorpe KE, Ogden LL, Galactionova K. Chronic conditions account for rise in Medicare spending from 1987 to 2006. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:718–24. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington: National Academies Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Redelmeier DA, Tan SH, Booth GL. The treatment of unrelated disorders in patients with chronic medical diseases. N EngI J Med. 1998;338:1516–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805213382106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002;288:2469–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract. 1998;1:2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barr VJ, Robinson S, Marin-Link B, Underhill L, Dotts A, Ravensdale D, et al. The expanded Chronic Care Model: an integration of concepts and strategies from population health promotion and the Chronic Care Model. Hosp Q. 2003;7:73–82. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2003.16763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. The Innovative Care for Chronic Conditions framework (ICCC) [cited 2011 Mar 22]. Available from: URL: http://www.who.int/diabetesactiononline/about/ICCC/en/index.html.

- 19.Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Stewart AL, Brown BW, Jr, Bandura A, Ritter P, et al. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial. Med Care. 1999;37:5–14. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199901000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Ritter PL, Laurent D, Hobbs M. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4:256–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bodenheimer T, Berry-Millett R. Care management of patients with complex health care needs. Princeton (NJ): Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2009. Dec, [cited 2011 Mar 22]. Also available from: URL: http://www.rwjf.org/files/research/021710.policysynthesis.caremanagement.rpt.revised.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown R. The promise of care coordination: models that decrease hospitalizations and improve outcomes for Medicare beneficiaries with chronic illness. March 2009. [cited 2011 Mar 22]. Available from: URL: http://www.americantelecare.com/pdfs/Promise%20of%20Care%20Coordination.pdf.

- 23.Department of Health and Human Services (US) HHS initiative on multiple chronic conditions. [cited 2011 Mar 22]. Available from: URL: http://www.hhs.gov/ash/initiatives/mcc/index.html.

- 24.Geyman JP. Disease management: panacea, another false hope, or something in between. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:257–60. doi: 10.1370/afm.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peikes D, Chen A, Schore J, Brown R. Effects of care coordination on hospitalization, quality of care, and health care expenditures among Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2009;301:603–18. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenthal TC. The medical home: growing evidence to -support a new approach to primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21:427–40. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.05.070287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US) [cited 2011 Mar 22];Screening works: update from the field. SAMHSA News 2008. 16(2) Also available from: URL: http://www.samhsa.gov/samhsa_news/volumexvi_2/article2.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alakeson V, Frank RG, Katz RE. Specialty care medical homes for people with severe, persistent mental disorders. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:867–73. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friedman B, Jiang HJ, Elixhauser A. Costly hospital readmissions and complex chronic illness. Inquiry. 2008–2009;45:408–21. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_45.04.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenhalgh T. Chronic illness: beyond the expert patient. BMJ. 2009;338:629–31. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lorig KR, Hurwicz M, Soel D, Hobbs M, Ritter PL. A national dissemination of an evidence-based self-management program: a process evaluation study. Patient Educ Counseling. 2004;59:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lorig KR, Ritter PL, Laurent DD, Plant K. Internet-based chronic disease self-management: a randomized trial. Med Care. 2006;44:946–71. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000233678.80203.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tinetti ME, Bogardus ST, Jr, Agostini JV. Potential pitfalls of disease-specific guidelines for patients with multiple conditions. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2870–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb042458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Darer JD, Hwang W, Pham HH, Bass EB, Anderson G. More training needed in chronic care: a survey of US physicians. Acad Med. 2004;79:541–8. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200406000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, Fried LP, Boult L, Wu AW. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294:716–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Norris SL, High K, Gill TM, Hennessy S, Kutner JS, Reuben DB, et al. Health care for older Americans with multiple chronic conditions: a research agenda. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:149–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Guide to community preventive services. [cited 2011 Mar 22]. Available from: URL: http://www.thecommunityguide.org/about/glossary.html.

- 38. Public Law 111-148, 111th Congress (2010).

- 39. Public Law 111-148, §3021.

- 40. Public Law 111-148, §2703.

- 41. Public Law 111-148, §3022.

- 42.National Conference on State Legislators. Accountable care organizations. Health Cost Containment and Efficiencies: NCSL Briefs for State Legislators May 2010;5:1-4. [cited 2011 Mar 22]. Also available from: URL: http://www.ncsl.org/portals/1/documents/health/ACCOUNTABLE_CARE-2010.pdf.

- 43.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to Congress: improving incentives in the Medicare program. Washington: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 2009. Jun, [cited 2011 Mar 22]. Also available from: URL: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/jun09_entirereport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fisher ES, Shortell SM. Accountable care organizations: accountable for what, to whom, and how. JAMA. 2010;304:1715–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Public Law 111-148, §3024.

- 46. Public Law 111-148, §3026.

- 47. Public Law 111-148, §2717.

- 48. Public Law 111-148, §4202.

- 49. Public Law 111-148, §6301.

- 50.National Quality Forum. Multiple chronic conditions measurement framework. [cited 2011 Mar 22]. Available from: URL: http://www.qualityforum.org/Projects/Multiple_Chronic_Conditions_Measurement_Framework.aspx.