Abstract

Weeds play an important role in agriculture and molecular techniques are useful to help understand traits that contribute to weediness and weeds' interactions with the environment. A total of 377 expressed sequence tags (ESTs) from a modest library were arranged into 227 unique fragments and 61 contigs, which consisted of two or more ESTs. From blastx results, we mapped and annotated unigenes using the gene ontology vocabulary according to biological process, cellular component and molecular function. These were then compared to a reference set of Arabidopsis thaliana sequences for statistically significant over- or underrepresented genes. The sequences were also compared against multiple protein databases for similarity of functional domains. Overall, the S. iberica sequences showed high similarity to response to stress, which included salt-induced proteins, betaine aldehydehyde dehydrogenase and calcium binding proteins. Only a modest number of transcripts were sequenced; however, the results presented here demonstrate the metabolic versatility of S. iberica in sub-optimal conditions that are likely to contribute to its cosmopolitan distribution. Here we propose that an EST library of an economically important weed species could be used to understand the weed's interactions with the environment.

Key words: expressed sequence tag, gene ontology, Salsola iberica, weed, weediness

Introduction

Weeds have always been a fundamental aspect of agriculture due to their significance in disturbing crop growth and limiting crop production. There are several methods of weed control and elimination that include mechanical, chemical and biological methods. It is now realized, in addition to improving crop traits, a greater understanding of weed transcriptional states and weed genomics is needed.1 There is a growing necessity of implementing genomic and transciptomic techniques to better understand the functional genomics aspect of weeds.2 High-throughput methods, such as genomic analyses, generate large data sets, often followed by computational methods for biological interpretation. Subsequently, Larrinua and Belmar3 have provided an in depth review on the importance that bioinformatics has on weed science research.

Salsola spp. are annual plants that grow in a variety of sub-optimal environments including arid and saline coastal soils. They are commonly found in disturbed areas, uncultivated grain fields and roadsides throughout the continental United States.4 Thought to have Eurasian origins, this weed has become naturalized in North America, Australia and elsewhere.5 For example, S. australis is a major weed in Australia.5 In Afghanistan and other parts of the Middle East S. imbricata is considered a serious weed6 and S. komarovi has been found growing on Korean sand dunes.7

Salsola spp. are commonly referred to as saltbush or tumbleweed. This reflects their ability to tolerate saline soils as well as their tumbling nature upon maturity, which facilitates seed dispersal. Mature, tumbling plants cause major disturbances by piling up against fences and houses, disrupting automobile traffic and clogging irrigation canals. In addition, Salsola spp. are major weeds in dryland farming and therefore play an important role in agriculture.8 More importantly, understanding how plants adapt and survive on saline soils is of significance since about one third of arable land is ranked as uncultivatable because of salinity.9

For these reasons we hypothesized that an over representation of GO terms associated with stress-related genes would be found with S. iberica sequences when compared to an A. thaliana reference set. In addition, due to its cosmopolitan distribution, ability to tolerate harsh environments, important role in agriculture and the paucity of current sequence data we created and annotated a small EST library of S. iberica to better understand some of its physiology and weediness traits and its interactions with the environment.

Results

Average cDNA insert size in the library was estimated to be 800 bp. Overall complexity of the library was estimated to be 5 × 105. For this library, a total of 768 clones were sequenced, of which 377 were of high enough quality to be used in this library. Using an E-value threshold 1.0 E-6, the distribution of sequences in the library showed that 99 (34%) S. iberica unigenes did not match sequences in the blastx database and therefore could not be mapped or annotated (Sup. File 1 and Fig. 1). From these, five unigenes could not be mapped and nine could not be annotated. The blastx hits from our Salsola library suggest that the 377 EST sequences were enough to show insight into mechanisms that play roles in plant physiological processes. The Blast2Go suite used in our analysis streamlined the process of batch blast and gene mapping and ontology assignments. The process entails three primary steps; similarity search using the NCBI-BLAST database (blastx), mapping the BLAST hits to multiple databases (e.g., Gene Ontology database, Protein Information Resource, Annex) and functional annotation according to Gene Ontology terms. The final step applies the ‘annotation rule’, which can only be applied after the first two steps. The rule attempts to determine the best annotation within a given reliability.10 Further analysis using the GOSSIP algorithm17 showed that there is a significant overrepresentation of interesting (i.e., weediness) GO-related terms affiliated with the S. iberica sequence data set (Table 1).

Figure 1.

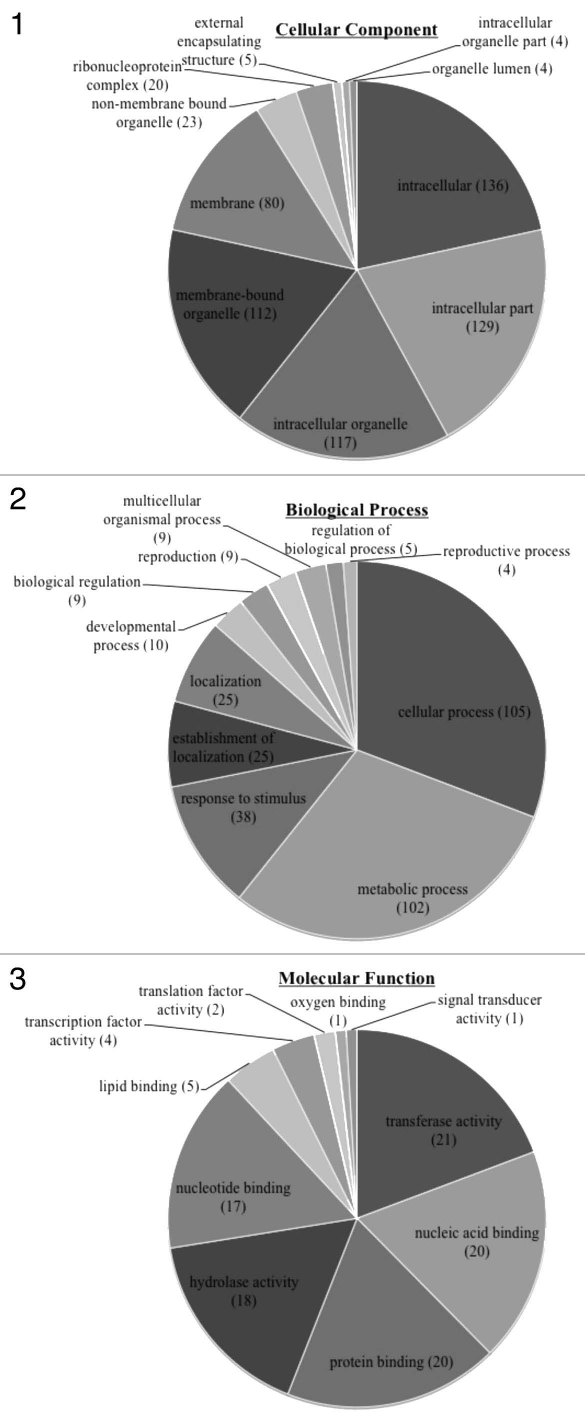

Pie diagrams showing the distribution of unigenes within their respective GO annotation categories (Biological Process, Molecular Function and Cellular Component). More than half of the annotated sequences of the biological process category were classified as a cellular or metabolic process while five sequences were annotated as regulating biological processes. The molecular function category classified the majority of sequences as having some type of binding activity. The cellular component category included many annotations related to organelles.

Table 1.

Results for Fisher's exact test showing gene ontology (GO) terms overrepresented in S. iberica when compared to the A. thaliana reference set.

| GO term | Name | FDR | FWER | Single test p-value | # in test group | # in reference group | # non annot test | # non annot reference group |

| GO:0005622 | intracellular | 8.27E-09 | 2.69E-08 | 0 | 136 | 8971 | 38 | 13587 |

| GO:0043231 | intracellular membrane-bounded organelle | 8.27E-09 | 2.69E-08 | 0 | 112 | 7396 | 62 | 15162 |

| GO:0043229 | intracellular organelle | 8.27E-09 | 2.69E-08 | 0 | 117 | 7808 | 57 | 14750 |

| GO:0044424 | intracellular part | 8.27E-09 | 2.69E-08 | 0 | 129 | 8595 | 45 | 13963 |

| GO:0015979 | photosynthesis | 8.27E-09 | 2.69E-08 | 0 | 29 | 155 | 145 | 22403 |

| GO:0009536 | plastid | 8.27E-09 | 2.69E-08 | 0 | 87 | 3195 | 87 | 19363 |

| GO:0043226 | organelle | 8.27E-09 | 2.69E-08 | 0 | 117 | 7809 | 57 | 14749 |

| GO:0009579 | thylakoid | 8.27E-09 | 2.69E-08 | 0 | 45 | 445 | 129 | 22113 |

| GO:0044444 | cytoplasmic part | 8.27E-09 | 2.69E-08 | 0 | 113 | 5919 | 61 | 16639 |

| GO:0043227 | membrane-bounded organelle | 8.27E-09 | 2.69E-08 | 0 | 112 | 7402 | 62 | 15156 |

| GO:0006091 | generation of precursor metabolites and energy | 8.27E-09 | 2.69E-08 | 0 | 29 | 301 | 145 | 22257 |

| GO:0016020 | membrane | 8.27E-09 | 2.69E-08 | 0 | 80 | 4606 | 94 | 17952 |

| GO:0005737 | cytoplasm | 8.27E-09 | 2.69E-08 | 0 | 125 | 6349 | 49 | 16209 |

| GO:0008152 | metabolic process | 1.21E-08 | 4.22E-08 | 8.97E-11 | 102 | 7822 | 72 | 14736 |

| GO:0005198 | structural molecule activity | 4.64E-08 | 1.74E-07 | 7.61E-10 | 21 | 509 | 153 | 22049 |

| GO:0005840 | ribosome | 7.86E-08 | 3.14E-07 | 1.53E-09 | 20 | 476 | 154 | 22082 |

| GO:0030529 | ribonucleoprotein complex | 7.61E-06 | 3.23E-05 | 1.43E-07 | 20 | 631 | 154 | 21927 |

| GO:0005623 | cell | 1.33E-05 | 5.97E-05 | 2.79E-07 | 148 | 15366 | 26 | 7192 |

| GO:0009987 | cellular process | 3.55E-05 | 1.68E-04 | 6.27E-07 | 105 | 9408 | 69 | 13150 |

| GO:0009058 | biosynthetic process | 6.51E-05 | 3.26E-04 | 1.46E-06 | 46 | 2911 | 128 | 19647 |

| GO:0044464 | cell part | 1.04E-04 | 5.46E-04 | 1.83E-06 | 146 | 15366 | 28 | 7192 |

| GO:0043232 | intracellular non-membrane-bounded organelle | 2.55E-04 | 0.00146728 | 5.71E-06 | 23 | 1028 | 151 | 21530 |

| GO:0043228 | non-membrane-bounded organelle | 2.55E-04 | 0.00146728 | 5.71E-06 | 23 | 1028 | 151 | 21530 |

| GO:0009628 | response to abiotic stimulus | 4.00E-04 | 0.00239535 | 9.22E-06 | 25 | 1217 | 149 | 21341 |

| GO:0005739 | mitochondrion | 0.00366101 | 0.0226216 | 5.85E-05 | 22 | 1113 | 152 | 21445 |

| GO:0006412 | translation | 0.00683275 | 0.0434415 | 1.63E-04 | 23 | 1282 | 151 | 21276 |

| GO:0044237 | cellular metabolic process | 0.0113657 | 0.0738504 | 2.28E-04 | 73 | 6577 | 101 | 15981 |

| GO:0006950 | response to stress | 0.0136289 | 0.0909947 | 3.23E-04 | 31 | 2086 | 143 | 20472 |

| GO:0034961 | cellular biopolymer biosynthetic process | 0.0330373 | 0.215949 | 7.95E-04 | 25 | 1623 | 149 | 20935 |

| GO:0043284 | biopolymer biosynthetic process | 0.0330373 | 0.219478 | 8.37E-04 | 25 | 1629 | 149 | 20929 |

| GO:0034645 | cellular macromolecule biosynthetic process | 0.0591195 | 0.367593 | 0.00154437 | 25 | 1703 | 149 | 20855 |

| GO:0009059 | macromolecule biosynthetic process | 0.0662273 | 0.411324 | 0.00168459 | 25 | 1714 | 149 | 20844 |

| GO:0006810 | transport | 0.0832994 | 0.497082 | 0.00248744 | 25 | 1765 | 149 | 20793 |

| GO:0010467 | gene expression | 0.0883478 | 0.528145 | 0.00252466 | 25 | 1767 | 149 | 20791 |

| GO:0051234 | establishment of localization | 0.0884048 | 0.538687 | 0.00267833 | 25 | 1775 | 149 | 20783 |

| GO:0016043 | cellular component organization | 0.0901766 | 0.555916 | 0.00292763 | 15 | 856 | 159 | 21702 |

| GO:0044238 | primary metabolic process | 0.0987281 | 0.598854 | 0.00324473 | 67 | 6456 | 107 | 16102 |

| GO:0051179 | localization | 0.116792 | 0.67038 | 0.00402214 | 25 | 1832 | 149 | 20726 |

Each GO term and name is provided with the corrected p value (FDR & FWER). # in test group, number of times term was found in S. iberica; # in reference group, number of times term was found in A. thaliana set; # non annot test, number of non-annotated in S. iberica set; # non annot reference group, number of non annotated in A. thaliana. FDR, corrected p-value by False Discovery Rate control; FWER, corrected p-value by Family Wise Error Rate; Single Test p Value: p Value without multiple testing corrections.

The level of GO annotations, in which detail of the description of a gene product increases with the GO level, varied across GO categories (Sup. File 1 and Fig. 2). Those categorized as having molecular function showed the highest GO annotation level, however most annotations were of cellular component. The majority of unigenes with cellular process were categorized at GO levels 4, 5 and 6. A total of 895 annotations were ascribed to all unigenes. In general, a longer sequence length resulted in an increased likelihood of being annotated (Sup. File 1 and Fig. 3). For example, less than half of the unigenes with a length of 200–300 bp were annotated while nearly all unigenes of 700–1,000 bp were annotated.

A total of 174 (60%) unigenes were mapped and annotated to GO terms. Annotated sequences were assigned to GO categories of biological process, cellular component and molecular process (Fig. 1). The criteria to place an annotation under a specific GO parent term (e.g., biological process) is based on a controlled vocabulary, which helps compare sequences across all species. Further, child terms (i.e., metabolic process) are associated with each parent term that give further description to an annotated sequence. Thus, in our data, a total of 341 annotations were described as playing a role in biological processes. Of these, 102 (30%) were categorized as having a role in metabolic processes and only four (<2%) were assigned to reproductive process. The majority of assignments were given to cellular process (105). Equal numbers of unigenes within the biological process category played a role in localization (25) or establishment of localization (25).

Within the molecular function category, a total of 109 annotations were assigned. These consisted of 63 (58%) annotations with some type of binding function (e.g., nucleic acid or protein binding). An additional 18 (17%) were categorized as having hydrolase activity or transferase activity (21). Only 6 (<6%) were annotated as having either translation factor or transcription factor activity.

A total of 630 annotations were categorized as cellular component. Of these, 136 (22%) were intracellular and 129 (20%) were categorized as an intracellular part. A total of 112 (18%) annotations were associated with membrane-bound organelles and only five (<1%) annotations played a role in external capsulating structure.

Implementation of the GOSSIP algorithm, which Blast2Go incorporates into their suite, showed an overrepresentation of GO terms according to annotated seqeunces (Table 1). This was based on the corrected p-value by false discovery rate (FDR) control (an FDR of 0.05 was used here). Importantly, these terms included “response to abiotic stimulus” (4.00E-4), “photosynthesis” (8.27E-9), “generation of precursor metabolites and energy” (8.27E-9) and “biosynthetic process” (6.51EE-5). Terms under “response to abiotic stress” were also overrepresented (FDR = 0.0136) in the S. iberica sequence set.

Discussion

Plant metabolism.

Many of the contigs generated were closely related to important plant metabolic processes. The largest contig consisted of nine ESTs and matched the photosystem I reaction center subunit (E-value = 6.03 E-45). The second largest contig consisted of six ESTs and coded for a ferrodoxin precursor. These findings are expected since the plant material was obtained from a young S. iberica, which would require photosynthesis for energy and anabolic processes. Another contig that consisted of sixESTs coded for phosphate dikinase, which is involved in carrying out phosphorylation reactions. The third largest EST-containing contigs consisted of four ESTs and coded for a lipid transfer protein and chlorophyll a/b binding protein. Additional matches to inorganic pyrohosphatase, 23 kDa oxygen evolving complex and S-adenosyl methionine synthetase were found for contigs each consisting of three ESTs. In addition to the many contigs matching photosynthetic and regulatory processes, one transcript encoded cytochrome c oxidase, which is important in cellular respiration.

Stress associations.

Many enzymes that play a role in abiotic stress response were found in S. iberica and included carbonic anyhydrase, catalase and glutathione peroxidase. Carbonic anyhydrase has previously exhibited increased levels in drought-stressed wheat leaves.11 Catalase is the enzyme that rapidly converts H2O2 molecules to less reactive species and it is well known that hydrogen peroxide molecules are produced in stressful conditions in plants.

Other sequences of interest were stress-enhanced proteins, temperature induced lipocalin, 2-cysteine peroxiredoxin and calcium ion binding proteins. Lipocalins are important for moving relatively small hydrophobic molecules across lipid membranes. The enzyme 2-cysteine peroxiredoxin, like catalase and glutathione peroxidase, is also important in reducing peroxide molecules. The importance of calcium ion binding proteins is important in many plant responses since calcium can act as a secondary messenger. It also is gaining increasing attention for its role in plant stress responses.12

Salsola spp. are also commonly called saltwort, due to their ability to tolerate saline soils. In addition, they are known for their drought and heat tolerance.6 It has been suggested that proline can help increase tolerance to osmotic stress. Sharifabad and Nodoushan19 studied the effects of salinity across three different Salsola species (S. dendroides, S. richteri and S. orientalis). They detected increasing proline levels correlated with increasing salinity. Here, we found at least one gene involved in production of glutamine (glutamine synthetase), a precursor to proline. Based on the annotations, we found at least six unigenes associated with salt stress response, which included cytochrome c oxidase subuint, glutathione peroxidase and an unknown plant salt-induced protein.

In previous studies, betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase has been shown to function in high salinity and drought stress.13 This enzyme catalyzes the last step of producing glycine betaine from choline in a two-step reaction.14 Glycine betaine is an important metabolite in salt stressed plants because of its ability to protect enzymes affiliated with photosynthesis.15 In this library we found one transcript coding for betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase. Three unigenes were found to be jasmonate-induced proteins. Jasmonate plays an important part of the abiotic and biotic plant stress response as a signaling hormone.

Proteins classified as heat shock proteins (HSPs), specifically HSP100 and HSP90 and HSP80 have been suggested to play a role in both development and stress response.16 Two transcripts from our S. iberica analysis closely matched HSP90 (E-value = 1.16 E-116), which is involved in stabilizing cellular proteins upon stress conditions. Koning et al.20 performed a northern blot and a GUS assay of a transgenic Arabidopsis line and showed that HSP80 is upregulated in development. These studies help present evidence that germinating seeds and young plants might often encounter abiotic stress factors and some of these genes might have evolved to help ensure proper development.

Materials and Methods

Library construction.

Plant tissue from a single individual growing in a parking lot on the University of Northern Colorado (Greeley, CO) campus was obtained and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was obtained using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) and mRNA was isolated using the polyA purist kit (Ambion, USA). Blunt ended cDNA was made from approximately 3 µg of mRNA using the OrientExpress cDNA synthesis kit with slight modifications (Novagen, USA). For nucleic acid precipitations, in place of ammonium acetate we used sodium acetate (0.3 M, pH 5.2).

To increase phosphorylation of 5′ and 3′ ends, the DNA Terminator End Repair Kit (Lucigen Corp., USA) was used. cDNA was size selected (700 bp-5 kb) using gel electrophoresis and electroelution. Approximately 250 ng of the blunt ended cDNA was ligated into the pSMART vector (Lucigen Corp., USA). Chemically competent E. coli were transformed with 1 µL of the ligation reaction.

To estimate insert size, eight colonies picked from an overnight culture were grown in LB broth overnight and plasmid extraction was performed using a plasmid miniprep kit (Qiagen, USA). A fast digest reaction using EcoRV (Fermentas, USA) and gel electrophoresis was performed to determine average insert size. The library was shipped to Lucigen Corp., USA for sequencing and read in one direction using an ABI 3730xl DNA sequencer.

Sequence analysis.

Sequencher software was used for vector and low quality sequence removal from a total 768 sequences resulted in 377 high-quality ESTs ranging from 200 bp-1,111 bp. Contig assembly yielded 227 fragments and 61 contigs consisting of 2 or more ESTs for a total of 288 unigenes. The resulting sequences were opened with the Blast2Go java application (www.blast2go.org/), freely available online.10 The Blast2Go suite allows for batch blast, functional analysis, assignment of gene ontology terms, statistical analysis and searching for functional domains via InterProScan (Sup. File 2). To increase specificity of gene ontology terms we used the GOSlim mapping function. To determine if our set of S. iberica sequences contained a statistically significant overrepresentation of GO terms we compared them to a reference set of GO terms for Arabidopsis thaliana.17

Future Perspectives

The science of weed control could be greatly improved with a molecular understanding of how weeds are able to outcompete crop species. Understanding the protein and genetic components of weeds can offer an important role in developing novel ways to help solve weed problems.18

Future research should include sequencing additional ESTs for Salsola to determine the additional diversity and abundance of transcripts. Construction and analysis of EST libraries of other cosmopolitan weed species might also be important to further the understanding of how weeds are able to live in areas most plants would find unbearable. In this paper we have developed an EST library of an important weed species and used the ESTs to understand part of the weed's transcriptome and its interactions with the environment. However, more wet lab data is needed to expand our analysis.

Data Deposition

Sequence data from this article have been deposited into GeneBank under accession numbers GW316091-GW316220, GW343231-GW343252,GW343255-GW343298, GW343301-GW343500.

Acknowledgements

The Blast2Go Google group was helpful in using the Blast2Go suite (http://groups.google.com/group/Blast2GO). This work was funded in part by the Colorado BioScience Grant and the GAANN Fellowship.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/12837

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Basu C, Halfhill MD, Mueller TC, Stewart CN., Jr Weed genomics: new tools to understand weed biology. Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9:391–408. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart CN, Tranel PJ, Horvath DP, Anderson JV, Rieseberg LH, Westwood JH, et al. Evolution of Weediness and Invasiveness: Charting the Course for Weed Genomics. Weed Sci. 2009;57:451–462. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larrinua IM. BSB. Bioinformatics and its relevance to weed science. Weed Science. 2008;56:297–305. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ayres D, Ryan FJ, Grotkopp E, Bailey J, Gaskin JF. Tumbleweed (Salsola, secion Kali) Species and Speciation in California. Biol Invasions. 2008;11:1175–1187. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borger CPD, Walsh M, Powles SB. Demography of Salsola australis populations in the agricultural region of south-west Australia. Weed Res. 2009;49:391–399. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan MA, Gul B, Weber DJ. Seed germination in the Great Basin halophyte Salsola iberica. Can J Bot. 2002;80:650–655. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim KD. Invasive plants on disturbed Korean sand dunes. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2005;62:353–364. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schillinger WF. Ecology and Control of Russian Thistle (Salsola Iberica) after Spring Wheat Harvest. Weed Sci. 2007;55:381–385. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frommer WB, Ludewig U, Rentsch D. Enhanced: Taking Transgenic Plants with a Pinch of Salt. Science. 1999;285:1222–1223. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5431.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conesa A, Gotz S, Garcia-Gomez JM, Terol J, Talon M, Robles M. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3674–3676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kicheva MI, Lazova GN. Response of carbonic anhydrase to polyethylene glycol-mediated water stress in wheat. Photosynthetica. 1997;34:133–135. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song WY, Zhang ZB, Shao HB, Guo XL, Cao HX, Zhao HB, et al. Relationship between calcium decoding elements and plant abiotic-stress resistance. Int J Biol Sci. 2008;4:116–125. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.4.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waditee R, Bhuiyan NH, Hirata E, Hibino T, Tanaka Y, Shikata M, et al. Metabolic engineering for betaine accumulation in microbes and plants. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:34185–34193. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704939200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hattori T, Mitsuya S, Fujiwara T, Jagendorf AT, Takabe T. Tissue specificity of glycinebetaine synthesis in barley. Plant Sci. 2008;176:112–118. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nomura M, Hibino T, Takabe T, Sugiyama T, Yokota A, Miyake H, et al. Transgenically produced glycinebetaine protects ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase from inactivation in Synechococcus sp. PCC7942 under salt stress. Plant Cell Physiol. 1998;39:425–432. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishna P, Gloor G. The Hsp90 family of proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2001;6:238–246. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2001)006<0238:thfopi>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blüthgen N, Kielbasa SM, Herzel H. Inferring combinatorial regulation of transcription in silico. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:272–279. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rector BG. Molecular biology approaches to control of intractable weeds: New strategies and complements to existing biological practices. Plant Sci. 2008;175:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heidari-Sharifabad H, Mirzaie-Nodoushan H. Salinity-induced growth and some metabolic changes in three Salsola species. J Arid environments. 2006;67:715–720. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koning AJ, Rose R, Comai L. Developmental expression of tomato heat-shock cognate protein 80. Plant Physiol. 1992;100:801–811. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.2.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.