Abstract

Plants are known to be highly responsive to environmental heterogeneity and normally allocate more biomass to organs that grow in richer patches. However, recent evidence demonstrates that plants can discriminately allocate more resources to roots that develop in patches with increasing nutrient levels, even when their other roots develop in richer patches. Responsiveness to the direction and steepness of spatial and temporal trajectories of environmental variables might enable plants to increase their performance by improving their readiness to anticipated resource availabilities in their immediate proximity. Exploring the ecological implications and mechanisms of trajectory-sensitivity in plants is expected to shed new light on the ways plants learn their environment and anticipate its future challenges and opportunities.

Key words: Gradient perception, phenotypic plasticity, anticipatory responses, plant behavior, plant learning

Natural environments present organisms with myriad challenges of surviving and reproducing under changing conditions.1 Depending on its extent, predictability and costs, environmental heterogeneity may select for various combinations of genetic differentiation and phenotypic plasticity.2–6 However, phenotypic plasticity is both limited and costly.7 One of the main limitations of phenotypic plasticity is the lag between the perception of the environment and the time the products of the plastic responses are fully operational.7 For instance, the developmental time of leaves may significantly limit the adaptive value of their plastic modification due to mismatches between the radiation levels and temperatures prevailing during their development and when mature and fully functional.8,9 Accordingly, selection is expected to promote responsiveness to cues that bear information regarding the probable future environment.9,10

Indeed, anticipatory responses are highly prevalent, if not universal, amongst living organisms. Whether through intricate cerebral processes, such as in vertebrates, nervous coordination, as in Echinoderms,11 or by relatively rudimentary non-neural processes, such as in plants12 and bacteria,13 accumulating examples suggest that virtually all known life forms are able to not only sense and plastically respond to their immediate environment but also anticipate probable future conditions via environmental correlations.10

Perhaps the best known example of plants' ability to anticipate future conditions is their responsiveness to spectral red/far-red cues, which is commonly tightly correlated with future probability of light competition.14 Among others, plants have been shown to respond to cues related to anticipated herbivory15,16 and nitrogen availability.17 Imminent stress is commonly anticipated by the perception of a prevailing stress. For example, adaptation to anticipated severe stress was demonstrated to be inducted by early priming by sub-acute drought,18 root competition19 and salinity.20

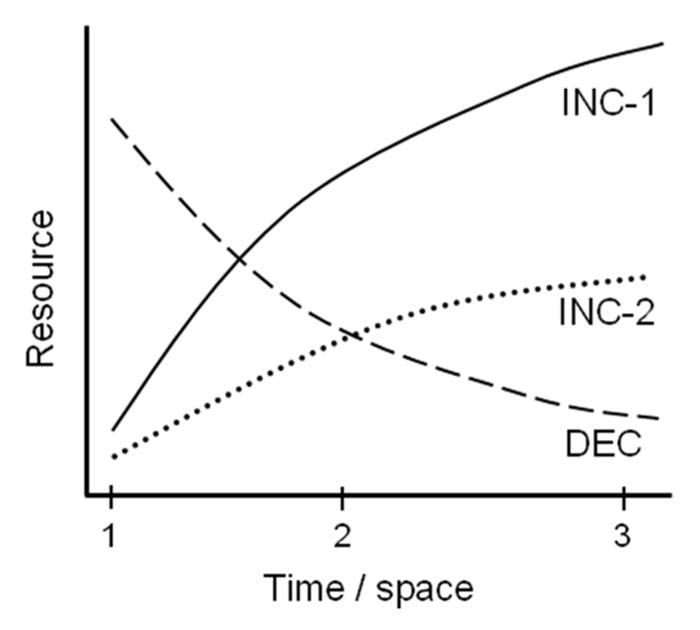

Future conditions can also be anticipated by gradient perception: because resource and stress levels are often changing along predictable spatial and temporal trajectories, spatio-temporal dynamics of environmental variables might convey information regarding anticipated growth conditions (Fig. 1). For example, the order of changes in day length, rather than day length itself, are known to assist plants in differentiating fall from spring and thus avoid blooming in the wrong season.21 In addition, responsiveness to environmental gradients as such, i.e., sensitivity to the direction and steepness of environmental trajectories, independently from the stationary levels of the same factors, has been demonstrated in higher organisms, such as the perception of acceleration in contrast to velocity;22 and the dynamics of skin temperature in contrast to stationary skin temperature;23 where the adaptive value of the second-order derivatives of environmental factors is paramount. Similar perception capabilities have also been demonstrated in rudimentary life forms such as bacteria (reviewed in refs. 13 and 24) and plants.25,26 Specifically, perception of environmental trajectories might assist organisms to both anticipate future conditions and better utilize the more promising patches in their immediate environment.27,28

Figure 1.

Trajectory sensitivity in plants. The hypothetical curves depict examples of spatio-temporal trajectories of resource availability, which might be utilized by plants to increase foraging efficiency in newly-encountered patches. When young or early-in-the-season (segment 1–2), plants are expected to allocate more resources to roots that experience the most promising (steepest increases or shallowest decreases) resource availabilities (e.g., allocating more resources to organs in INC-1 than INC-2). In addition, plants are predicted to avoid allocation to roots experiencing decreasing trajectories (DEC, segment 1–2); although temporarily more abundant with resources, such DEC patches are expected to become poorer than alternative patches in the longer run (segment 2–3).29 However, responsiveness to environmental trajectories is only predicted where the expected period of resource uptake is relatively long, e.g., when plants are still active in segment 2–3, a stipulation which might not be fulfilled in e.g., short-living annuals with life span shorter than segment 1–2.

In a recent study, Pisum plants have been demonstrated to be sensitive to temporal changes in nutrient availabilities. Specifically, plants allocated greater biomass to roots growing under dynamically-improving nutrient levels than to roots that grew under continuously higher, yet stationary or deteriorating, nutrient availabilities.29 Allocation to roots in poorer patches might seem maladaptive if only stationary nutrient levels are accounted for, and indeed-almost invariably, plants are known to allocate more resources to organs that experience higher (non-toxic) resource levels (reviewed in ref. 33). Accordingly, the new findings suggest that rather than merely responding to the prevailing nutrient availabilities, root growth and allocation are also responsive to trajectories of nutrient availabilities (Fig. 1).10

Although Shemesh et al.29 demonstrated trajectory-sensitivity of individual roots to temporal gradient of nutrient availabilities, it is likely that this sensitivity helps plants sense spatial gradients, whereby root tips perceive changes in growth conditions as they move through space.34 Interestingly, because the trajectory-sensitivity was observed when whole roots were subjected to changing nutrient levels, it is likely that trajectory sensitivity in roots is based on the integration of sensory inputs perceived by yet-to-be-determined parts of the root over time, i.e., temporal sensitivity/memory (e.g. reviewed in ref. 35), rather than on the integration of sensory inputs at different locations on the same individual roots (i.e., spatial sensitivity).

Besides the direction of change, it is hypothesized that plants are also sensitive to the steepness of environmental trajectories (Fig. 1). This might be especially crucial in short-living annuals, which are expected to only be responsive to trajectories steep enough to be indicative of changes in growth conditions before the expected termination of the growth season (Fig. 1).

Studying responsiveness to environmental variability is pivotal for understanding the ecology and evolution of any living organism. However, until recently most attention has been given to the study of responses to stationary spatial and temporal heterogeneities in growth conditions. Exploring the ecological implications and mechanisms of trajectory sensitivity in plants is expected to shed new light on the ways plants learn their immediate environment and anticipate its future challenges and opportunities.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported in part by a research grant from the Israel Science Foundation to A.N. This is publication no. 708 of the Mitrani Department of Desert Ecology.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/13660

References

- 1.Caldwell MM, Pearcy RW, editors. Exploitation of Environmental Heterogeneity by Plants. New York: Academic Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradshaw AD. Evolutionary significance of phenotypic plasticity in plants. Adv Genet. 1965;13:115–155. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schlichting CD. The evolution of phenotypic plasticity in plants. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1986;17:667–693. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alpert P, Simms EL. The relative advantages of plasticity and fixity in different environments: when is it good for a plant to adjust? Evol Ecol. 2002;16:285–297. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levins R. Evolution in changing environments. New Jersey: Princeton University Press; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sultan SE. Phenotypic plasticity for plant development, function and life history. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:537–542. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(00)01797-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeWitt TJ, Sih A, Wilson DS. Costs and limits of phenotypic plasticity. Trends Ecol Evol. 1998;13:77–81. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(97)01274-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Givnish TJ. Ecological constraints on the evolution of plasticity in plants. Evol Ecol. 2002;16:213–242. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aphalo PJ, Ballare CL. On the importance of information-acquiring systems in plant-plant interactions. Funct Ecol. 1995;9:5–14. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Novoplansky A. Picking battles wisely: plant behaviour under competition. Plant Cell Environ. 2009;32:726–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.01979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suarez-Castillo EC, Medina-Ortiz WE, Roig-Lopez JL, Garcia-Arraras JE. Ependymin, a gene involved in regeneration and neuroplasticity in vertebrates, is overexpressed during regeneration in the echinoderm Holothuria glaberrima. Gene. 2004;334:133–143. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trewavas A. Aspects of plant intelligence. Ann Bot (Lond) 2003;92:1–20. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcg101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisenbach M. A hitchhiker's guide through advances and conceptual changes in chemotaxis. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:574–580. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith H. Phytochromes and light signal perception by plants—an emerging synthesis. Nature. 2000;407:585–591. doi: 10.1038/35036500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kessler A, Baldwin IT. Plant responses to insect herbivory: The emerging molecular analysis. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2002;53:299–328. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.100301.135207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heil M, Karban R. Explaining evolution of plant communication by airborne signals. Trends Ecol Evol. 2010;25:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forde B, Zhang HM. Response: nitrate and root branching. Trends Plant Sci. 1998;3:204–205. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Passioura JB. Root Signals Control Leaf Expansion in Wheat Seedlings Growing in Drying Soil. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1988;15:687–693. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Novoplansky A, Goldberg D. Interactions between neighbour environments and drought resistance. J Arid Environ. 2001;47:11–32. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ackerson RC, Youngner VB. Responses of Bermudagrass to salinity. Agron J. 1975;67:678–681. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heide OM. Dual induction rather than intermediate daylength response of flowering in Echinacea purpurea. Physiol Plant. 2004;120:298–302. doi: 10.1111/j.0031-9317.2004.0228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Widmaier EP, Raff H, Strang KT. Vander's Human Physiology. NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livingston RB, editor. Neurophysiology. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vladimirov N, Sourjik V. Chemotaxis: how bacteria use memory. Biol Chem. 2009;390:1097–1104. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weijschede J, Martinkova J, de Kroon H, Huber H. Shade avoidance in Trifolium repens: costs and benefits of plasticity in petiole length and leaf size. New Phytol. 2006;172:655–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leeflang L, During HJ, Werger MJA. The role of petioles in light acquisition by Hydrocotyle vulgaris L. in a vertical light gradient. Oecologia. 1998;117:235–238. doi: 10.1007/s004420050653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spieler M, Linsenmair KE. Choice of optimal oviposition sites by Hoplobatrachus occipitalis (Anura: Ranidae) in an unpredictable and patchy environment. Oecologia. 1997;109:184–199. doi: 10.1007/s004420050073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denver RJ, Mirhadi N, Phillips M. Adaptive plasticity in amphibian metamorphosis: Response of Scaphiopus hammondii tadpoles to habitat desiccation. Ecology. 1998;79:1859–1872. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shemesh H, Arbiv A, Gersani M, Ovadia O, Novoplansky A. The effects of nutrient dynamics on root patch choice. PLoS One. 2010;5:10824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hodge A. Root decisions. Plant Cell Environ. 2009;32:628–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sachs T, Novoplansky A. The ecology and evolution of clonal plants. Backhuys Publishers; 1997. What does aclonal organization suggest concerning clonal plants? pp. 55–77. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Snow R. Experiments on growth and inhibition. II. New phenomena of inhibition. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1931;108:305–316. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Novoplansky A. Developmental responses of individual Onobrychis plants to spatial heterogeneity. Vegetatio. 1996;127:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baluska F, Mancuso S, Volkmann D, Barlow PW. Root apex transition zone: a signalling-response nexus in the root. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:402–408. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ripoll C, Le Sceller L, Verdus MC, Norris V, Tafforeau M, Thellier M. Plant-Environment Interactions: From Sensory Plant Biology to Active Plant Behavior. Springer-Verlag Berlin; 2009. Memorization of Abiotic Stimuli in Plants: A Complex Role for Calcium; pp. 267–283. [Google Scholar]