Abstract

The import of diverse nucleus-encoded proteins into chloroplasts is crucial for plant life. Although this crosstalk is mainly dependent on specific transit peptides, it has been recently reported that a non protein-coding RNA (ncRNA) based on a viroid-derived sequence (vdRNA) and acting as a 5′ UTR-end mediates the functional import of GFP-mRNA into chloroplasts. This observation unearths a novel plant cell-signaling pathway able to control the accumulation of the nuclear-encoded proteins in this organelle. The mechanisms regulating this chloroplastspecific localization remain yet unclear. To unravel the functional nature of this chloroplastic signal, here we dissect the 5′UTR-end responsible for the chloroplast targeting. A confocal microcopy analysis in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves of the transcripts expression carrying partial deletions of the 5′UTR-end indicates that an internal 110 nucleotides-length fragment is sufficient to mediate the traffic of functional GFP-mRNA into chloroplasts. However, the capability of this motif to act as a chloroplastic localization signal was enhanced when fused to either the 5′ or the 3′ region of the vd-5′ UTR sequence. These findings suggest that the chloroplast-specific RNA targeting is dependent on a structural motif rather than on the RNA sequence.

Key words: Chloroplast signalling, RNA import, viroids, RNA localization, nucleus, non-coding RNAs

The structural and functional compartmentalization generated by the plant cells during their evolution required that diverse synthesized proteins were targeted to specifics cell organelles and compartments in which they play specific roles. Chloroplasts are specialized organelles, of cyanobacterial origin, that are of crucial importance for the photosynthetic cells. During their adaptation to the host plant-cell they lost their autonomy and consequently most of the proteins that constitute the functional chloroplast are nucleus-encoded. This functional interrelation is mediated by proteins encoded in the nucleus, synthesized in the cytosol in the corresponding precursor forms (containing a targeting signal called transit peptide, TP) and then imported into the organelle.1–4 However, this functional model fails to explain the chloroplastic accumulation of the diverse nucleus-encoded proteins lacking canonical transit peptides.5,6

Evidence from high-throughput sequence methods has revealed the existence in eukaryotic organisms of a large number of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) that have been recognized as regulators of gene expression playing roles previously believed to correspond to proteins.7–10

In a recent work, we have shown that a non-coding RNA (ncRNA) sequence acting as a 5′UTR end mediates the specific trafficking and accumulation of a functional foreign mRNA into N. benthamiana chloroplasts.11 This evidence was obtained by transiently expressing an engineered reporter containing an RNA derived from a viroid member of the Avsunviroidae family (a class of sub viral plant pathogens that accumulate in chloroplasts),12 which was fused as a 5′UTR end to the Green Fluorescence protein (GFP) mRNA (vd-5′ UTR/GFP).

The specific localization of the chimeric transcripts was demonstrated by the observation at confocal microscopy of a selective accumulation of GFP in the chloroplast of leaves expressing the vd-5′ UTR/GFP and by the RT-PCR detection of the GFP mRNA in chloroplasts isolated from cells expressing this construct. These two complementary approaches were employed as the experimental basis to propose a novel signaling pathway between the nucleus and the chloroplasts regulated by non-coding RNAs.11 This emergent paradigm highlights a novel host-modulated regulatory mechanism that would be potentially able to control the gene expression and the accumulation of the nuclear-encoded proteins in chloroplasts, as an alternative mechanism to the transit peptides-based one.

We consider that the specific trafficking of nuclear-encoded mRNA, mediated by ncRNA signals, can only be explained assuming the existence of cellular factors that are capable of recognizing the ncRNA in the nucleus and mediating its specific transit into chloroplasts. However, the mechanism involved in the regulation of this selective interaction still remains unknown. Assuming that this biological function is mediated by the 5′UTR end per se the interaction with the unknown cellular factors would require the identification of structural elements or consensus sequences in this regulatory ncRNA molecule.

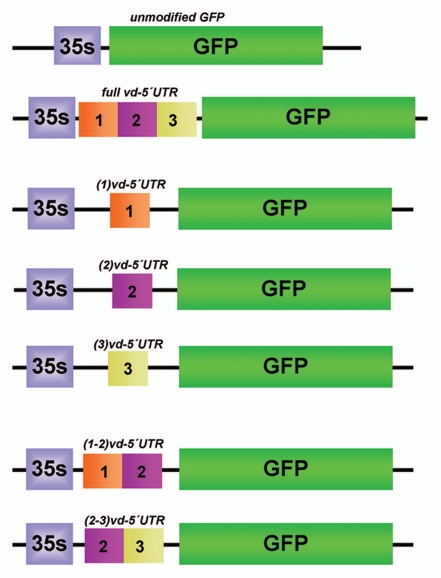

To obtain a more detailed picture, we dissected the vd-5′UTR chloroplastic signal into three arbitrary regions identified as I (108 nt) left, II (110 nt) internal and III (112 nt) right and generated constructs containing these partials 5′UTR ends transcriptionally fused to the GFP-cDNA (Fig. 1). The chimeric cDNAs were cloned in a binary vector and transfected into Agrobacterium tumefaciens. The functionality of the different transcription products was analyzed by comparing their transient expression in N. benthamiana plants in agroinfiltration assays.

Figure 1.

Physical map of the partially deleted vd-5′UTR/GFP constructs used in this work. The full vd-5′UTR chloroplastic signal (AN-HM136583) was dissected into three arbitrary regions: I (108 nt) left, II (110 nt) internal and III (112 nt) right. Those constructs containing different combinations of these partial vd-5′ UTR ends transcriptionally fused to the GFP-cDNA are shown in detail.

We observed that the GFP arising from the chimeric transcripts carrying the (1)vd-5′UTR and (3)vd-5′UTR ends was uniformly distributed in the nucleus and cytoplasm of the analyzed cells, resembling the localization of the unmodified GFP used as a control (Fig. 2). However, the (2)vd-5′UTR/GFP showed a dual localization pattern, and either specifically accumulated in the chloroplasts in certain cells or was uniformly distributed in the nucleus and cytoplasm in other examined cells. This finding reveals that region I of the vd-5′UTR end is sufficient to mediate the traffic of functional GFP-mRNA into chloroplasts, indicating that the chloroplast-specific signal is localized in this 110 nt-length region. Interestingly, the efficiency of the chloroplast-specific accumulation of this motif was significantly enhanced when fragment II was complemented with either non-chloroplast specific I or III regions of the vd-5′UTR end (Fig. 2). It is worth mentioning here that in all the assays performed, the accumulation of both (1–2)vd-5′UTR/GFP and (2–3)vd-5′UTR/GFP in chloroplasts was notably lower than that observed with the full vd-5′UTR/GFP construct (Fig. 2). Finally, a comparative analysis of the viroid-derived region 2 with other ncRNAs or mRNAs revealed no significant similarity.

Figure 2.

Region 2 of the vd-5′UTR end mediates chloroplast-specific trafficking. Observation at confocal microscope of the N. benthamiana leaves expressing the different combinations of the deleted vd-5′UTR end transcriptionally fused to the GFP (see the text for details). The unmodified GFP and the full vd-5′UTR /GFP constructs were used as cellular localization controls.

These results strongly suggest that, in our experimental model, the specific import of functional mRNA into chloroplast is mediated by an undefined secondary or tertiary structural domain localized in the central region of the vd-5′UTR end, able to mediate the specific accumulation of GFP-mRNA into chloroplasts. Furthermore the signaling efficiency of this region is enhanced when the theoretical structural RNA domain is stabilized by one or both of the adjacent 5′ and 3′ RNA regions of the full vd-5′UTR signal. This predicted RNA recognition mechanism is consistent with that described for numerous non-coding RNAs whose biological functions must be dictated primarily by their structural motifs rather than by their sequences.7–10 However, the possibility of specific RNA sequences being involved in the regulation of this signaling mechanism can not be excluded.

In this context, additional experimental approaches, such as the determination of the structural RNA motifs or the identification of the potential cell factors involved in their recognition, are necessary to validate this predicted functional mechanism.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/13711

References

- 1.Woodson JD, Chory J. Coordination of gene expression between organellar and nuclear genomes. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:383–395. doi: 10.1038/nrg2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jarvis P. Targeting of nucleus-encoded proteins to chloroplasts in plants. New Phytol. 2008;179:257–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pogson BJ, Woo NS, Fórster B, Small ID. Plastid signaling to the nucleus and beyond. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13:602–609. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruce BD. Chloroplast transit peptides: structure, function and evolution. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:440–447. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01833-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nada A, Soll J. Inner envelope protein 32 is imported into chloroplasts by a novel pathway. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:3975–3982. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleffmann T, Russenberger D, von Zychlinski A, Christopher W, Sjólander K, Gruissem W, et al. The Arabidopsis thaliana chloroplast proteome reveals pathway abundance and novel protein functions. Curr Biol. 2004;14:354–362. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rymarquis LA, Kastenmayer JP, Hüttenhofer AG, Green P. Diamonds in the rough: mRNA-like ncRNAs. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13:329–334. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilusz JE, Sunwoo H, Spector DL. Long noncoding RNAs: functional surprises from the RNA world. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1494–1504. doi: 10.1101/gad.1800909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hannapel DJ. A model system of development regulated by the long-distance transport of mRNA. J Integr Plant Biol. 2010;52:40–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mattick J. Non-coding RNAs and eukatyotic evolution—a personal view. BMC Biol. 2010;8:67. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gómez G, Pallás V. Noncoding RNA mediated traffic of foreign mRNA into chloroplasts reveals a novel signaling mechanism in plants. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:12269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding B. The biology of viroid-host interactions. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2009;47:105–131. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080508-081927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]