Abstract

Assessment of bone loss and osteoporosis by ultrasound systems is based on the speed of sound and broadband ultrasound attenuation of a single wave. However, the existence of a second wave in cancellous bone has been reported and its existence is an unequivocal signature of poroelastic media. To account for the fact that ultrasound is sensitive to microarchitecture as well as bone mineral density (BMD), a fabric-dependent anisotropic poroelastic wave propagation theory was recently developed for pure wave modes propagating along a plane of symmetry in an anisotropic medium. Key to this development was the inclusion of the fabric tensor—a quantitative stereological measure of the degree of structural anisotropy of bone—into the linear poroelasticity theory. In the present study, this framework is extended to the propagation of mixed wave modes along an arbitrary direction in anisotropic porous media called quasi-waves. It was found that differences between phase and group velocities are due to the anisotropy of the bone microarchitecture, and that the experimental wave velocities are more accurately predicted by the poroelastic model when the fabric tensor variable is taken into account. This poroelastic wave propagation theory represents an alternative for bone quality assessment beyond BMD.

INTRODUCTION

Ultrasound waves have a broad range of clinical applications as a non-destructive testing approach to image and diagnose medical conditions. In particular, quantitative ultrasound has been considered as an attractive alternative to the use of Dual Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry (DEXA) to diagnose osteoporosis (Siffert and Kaufman, 2006; Hans et al., 1996; Grimm and Williams, 1997a) because it is non-ionizing, inexpensive, and non-invasive. Ultrasound waves are elastic vibrations that can provide direct information on the mechanical properties of the medium in which they propagate. Unfortunately, ultrasound wave propagation phenomena in anisotropic poroelastic medium are highly complex. This complexity has limited the development and application of ultrasound approaches to assess bone status and osteoporosis when compared to the development and application of DEXA systems. A major limitation associated with current clinical ultrasound systems (Grigorian et al., 2002)—often called ultrasound densitometers—consist of determining bone mass density as DEXA does, without taking advantage of the fact that ultrasound is sensitive to microarchitecture and tissue composition (Sakata et al., 2004; Xia et al., 2007; Mizuno et al., 2008; Sasso et al., 2008; Lin et al., 2009).

In most clinical ultrasound densitometer systems, only one wave arriving to the ultrasound probe is identified. If only one wave is measured, the analysis is limited to an “equivalent medium approach” in which the solid trabecular structure cannot be distinguished from the fluid within the pores. However, the existence of a second wave in cancellous bone has been reported in vitro (Hosokawa and Otani, 1997, 1998, 42; Cardoso et al., 2001, 2003, 17; Mizuno et al., 2009). These two waves propagate with different velocities (Wear et al., 2005; Anderson et al., 2008, 2009, 2; Wear, 2009; Nguyen et al., 2010; Wear, 2010) and have been shown to correspond to the fast and slow waves predicted by Biot’s (Biot, 1941, 1955, 1956a,b, 1962a,b, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14) poroelastic wave propagation theory. Therefore, a poroelastic wave propagation theory is conceptually more appropriate than an equivalent media approach to characterize the properties of the porous medium.

Isotropic poroelasticity theory has been used for many years to analyze wave propagation in cancellous bone (Williams, 1992; Hosokawa and Otani, 1997, 1998, 42; Haire and Langton, 1999; Kaczmarek et al., 2002; Fellah et al., 2004; Wear et al., 2005; Pakula et al., 2008; Fellah et al., 2008; Sebaa et al., 2008; Cardoso et al., 2008), and just recently the role of microarchitecture has been included in poroelasticity theory through the fabric tensor (Cowin and Cardoso, 2011). Most clinical ultrasound densitometers depend on empirical relationships between the speed of sound (SOS), broadband ultrasound attenuation (BUA), and bone density in order to assess bone loss. In contrast, the fabric-dependent anisotropic poroelastic approach proposed by Cowin and Cardoso (2011) has the advantage of providing a theoretical framework to describe the relationship between measurable wave properties (i.e., wave velocity and attenuation) and the elastic constants of the trabecular bone structure. Key to the development of such a theory was the incorporation of the fabric tensor into the governing equations for wave motion in the linear theory of anisotropic poroelastic materials (Cowin, 1985, 1986, 1999, 2004, 24; Cowin and Mehrabadi, 2007, 24). Fabric is a quantitative stereological measure of the degree of structural anisotropy in the pore architecture of a porous medium (Hilliard, 1967; Whitehouse, 1974; Whitehouse and Dyson, 1974; Cowin and Satake, 1978; Satake, 1982; Kanatani, 1983, 1984a,b, 1985, 48, 49, 50; Harrigan and Mann, 1984; Odgaard, 1997, 2001, 64; Odgaard et al., 1997, Matsuura et al., 2008). This new approach resulted in a poroelastic Christoffel equation for anisotropic poroelastic media represented by an eigenvalue problem with a characteristic polynomial equation of order 6. Four of those six roots are nonzero, and correspond to the four wave modes of propagation in porous media, two of which are longitudinal and two are shear wave modes. Analytical expressions were given in Cowin and Cardoso (2011) for the velocity and attenuation of each wave mode for the case in which the direction of wave propagation coincides with the normal to a plane of symmetry of the anisotropic medium. Since this poroelastic wave propagation theory depends on anisotropy of the structure and tissue composition in addition to bone mass density, it represents an alternative for bone quality assessment beyond bone mineral density (BMD).

In the present study, the theoretical framework of Cowin and Cardoso (2011) is extended to the propagation of waves along an arbitrary direction in orthotropic porous media. The plane wave equation in an anisotropic fluid-saturated poroelastic medium developed in Cowin and Cardoso (2011) is reviewed in Sec. 2. The fabric dependence of tensors appearing in the poroelastic model of wave propagation is summarized in Sec. 3. The propagation of plane waves in an anisotropic, fabric-dependent, saturated porous medium along an arbitrary direction is derived in Sec. 4, and the practical application of these results to the wave propagation in trabecular bone is presented in Sec. 5. The final section, Sec. 6, contains our discussion and concluding remarks.

PLANE WAVE EQUATION IN AN ANISOTROPIC FLUID-SATURATED POROELASTIC MEDIUM

The field equations of motion in an anisotropic porous medium (Biot, 1941) were obtained from the conservation of linear momentum and the conservation of mass by substituting constitutive equations for stress and fluid flux (Cowin and Cardoso, 2011). The field equations describe the solid displacement field u and the displacement field w of the fluid relative to the solid,

| (1) |

| (2) |

where ρ is the bulk density of the solid matrix, ρf is the density of the pore fluid, μ is the viscosity of the pore fluid, and M is the constant of proportionality between the fluid pore pressure, p, and the variation in fluid content, ζ. The variation in fluid content, ζ, a traditional Biot variable, is defined as the divergence of the displacement vector w of the fluid relative to the solid, ζ = −∇·w. Also, the Biot effective stress coefficient tensor A represents the proportionality factor between the stress tensor T and the pore fluid pressure p, , where Tij are the components of the stress tensor and represents the components of the drained elasticity tensor. The four constitutive tensors, Zijkm, Mij, jij, and, Rij, appearing in Eqs. 1, 1 are identified as follows: Zijkm is Biot’s elasticity tensor—Zijkm differs from the drained elasticity tensor by the term MAijAkm, which is the open product of the Biot effective stress coefficient tensor A with itself; Mij is directly related to the Biot effective stress coefficient tensor A and the scalar M by Mij = MAij; the constant M is related to the effective drained elastic stiffness tensor , the drained compliance tensor , and the Biot’s effective stress tensor Aij by

| (3) |

Jij is the micro–macro velocity average tensor—it functions as a density distribution function that relates the relative micro-solid-fluid velocity to its bulk volume average , and Rij is the flow-resistivity tensor, the reciprocal of the permeability tensor Kij. Throughout this study, Einstein’s convention of summing over repeated indices was adopted.

The propagation of plane waves in an anisotropic fluid-saturated porous medium is represented kinematically by a direction of propagation, denoted by n = (n1, n2, n3)T a unit normal to the wave front, and a or b, which are the directions of displacement for the wave fronts associated with u and w, respectively. These two plane waves are represented by

| (4) |

where v is the wave phase velocity in the direction n, x is the position vector, ω is the frequency, and t is the time. The relationship between the complex phase velocity v and frequency ω of attenuating waves is represented by

| (5) |

The imaginary part α is related to the wave attenuation as a function of traveled distance (e−αn·x) and the real part k describes the wave number associated to the wave propagating in the direction n. A transverse wave is characterized by a·n = 0, a longitudinal wave by a·n = 1. Substituting the relations (4) for the plane waves into the field equations 1, 2 leads to the poroelastic Christoffel equation6

| (6) |

where the notation Qik = Zijkmnmnj and Cik = Mijnjnk has been introduced.

Equation 6 represents an eigenvalue problem, the squares of the wave speeds v2 representing the eigenvalues, and the vectors a and b representing the eigenvectors. Since the right hand side of this linear system of equations is a zero 6D vector, it follows from Cramer’s rule that, in order to avoid the trivial solution, it is necessary to set the determinant of the 6 by 6 matrix equal to zero, thus

| (7) |

where the notation has been introduced.

FABRIC DEPENDENCE OF TENSORS APPEARING IN THE POROELASTIC MODEL OF WAVE PROPAGATION

The second rank fabric tensor F is a non-dimensional quantitative stereological measure of the degree of structural anisotropy in the pore architecture of a porous medium. The experimental procedure for the surface area orientation measurement of cancellous bone is described by Whitehouse (1974), Whitehouse and Dyson (1974), Harrigan and Mann (1984), and Turner et al. (1987, 1990), 79 The work of these authors, and Odgaard (1997, 2001), 64, Odgaard et al. (1997), van Rietbergen et al. (1996, 1998), 82, Matsuura et al. (2008) and others, has shown that the fabric tensor is a good measure of the structural anisotropy in cancellous bone tissue (Cowin, 1997).

The second rank fabric tensor F is symmetric, therefore its invariants IF, IIF, and IIIF are related to the traces of F, F2, and F3 by the formulas recorded, for example, in Ericksen (1960),

| (8) |

The fact that a matrix satisfies its own characteristic equation, the Cayley–Hamilton theorem, is then written in the form

| (9) |

The significance of this result is that any power of F of the order three or higher may be eliminated by repetitive use of this result. From the first and second equations of Eq. 8 one can see that trF2 = I2 − 2II. Using the Cayley–Hamilton theorem it is easy to show that

| (10) |

These results will be used below. Finally, we normalize the fabric tensor by setting I = trF = 1. Thus in the applications of the formula trF2 = I2 − 2II and Eq. 10, I is replaced by 1. The Cayley–Hamilton theorem is here used not only on the fabric tensor but also on other second rank tensors such as R, K, M, and J. Formulas relating the acoustic tensor Z, the flow-resistivity tensor R, and the tensor M, representing the interaction of the velocity fields u and w, to the fabric tensor F were obtained in Cowin and Cardoso (2011).

Briefly, the dependence of the elastic acoustic tensor Z upon the fabric tensor F is described by the following relationships:

| (11) |

The tensor M represents the elastic coupling between the solid and the fluid phases,

| (12) |

The micro–macro velocity average tensor J is related to the fabric by

| (13) |

Similarly, the flow-resistivity tensor R is related to the fabric by

| (14) |

where the quantities , , , , , , , , , , , , j1, j2, j3, r1, r2, and r3 are scalar-valued functions of ϕ, IIF, and IIIF (Cowin, 1985; Cowin and Cardoso, 2011). R is the inverse of the second rank intrinsic permeability tensor K and it represents dissipation phenomena due to viscous losses at low frequencies of fluid motion. The conception of K was extended to take into account the change in fluid flow regime occurring between low and high frequencies of wave propagation (Johnson et al., 1987)

| (15) |

where the dynamic permeability tensor K is a function of the average intrinsic permeability κ0, the fabric tensor, and Bessel functions that characterize the dynamics of the oscillatory fluid flow inside a cylindrical channel. In this equation, J1 and J0 are, respectively, the first order and zeroth order Bessel functions of the first kind, and d corresponds to the average characteristic pore dimension. The inverse of the viscous skin depth χ is defined as a function of the angular frequency ω, the fluid mass density ρf, and the dynamic viscosity of the fluid μ,

| (16) |

PROPAGATION OF WAVES ALONG AN ARBITRARY DIRECTION IN ORTHOTROPIC POROUS MEDIA

Phase velocity and phase direction

In the principal coordinate system of the fabric tensor, the poroelastic Christoffel equation 7 for wave propagation in an arbitrary direction n = (n1,n2, n3)T can be written as

| (17) |

where the detailed algebraic structure of the tensors Q, C, and S as functions of the general direction of wave propagation n are recorded in the Appendix. The characteristic equation of system (17) is represented by a sixth order polynomial in z = v2, given by

| (18) |

where the c0(n) to c6(n) coefficients are:

| (19) |

where

| (20) |

The eigenvalues zm (m = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6) of the poroelastic Christoffel equation 17 provides the values of the possible squares of the wave phase speeds in a fluid-saturated porous medium. The phase velocity is defined as the propagation velocity of a point of constant phase (ωt – kx = const, thus v = (dx∕dt) = ω∕k). Each phase velocity vm is related to the common angular frequency ω and its own wave vector km,

| (21) |

In a general direction, n, there will be six roots of which four are non-trivial wave speeds, two shear waves and two longitudinal modes, representing Biot’s fast and slow waves. Only waves propagating along the axes of symmetry are considered as pure wave modes (m = P1, P2, S1, and S2), while waves propagating off axes of symmetry are composed of mixed modes and called quasi-waves (m = qP1, qP2, qS1, and qS2). For each value of a squared wave speed substituted back into Eq. 7, two three-dimensional (3D) vectors a and b will be determined subject to the condition that they are both unit vectors. For an isotropic medium, the wave number is a scalar quantity and the phase velocity v is constant for any direction n. For an anisotropic medium, the wave number k becomes a vector k(k1,k2,k3) and the associated phase velocity vector v(v1,v2,v3) varies with the direction of wave propagation n. An alternate approach to the solution of Eq. 6, for the squares of the wave speeds v2 and the two 3D vectors a and b, has been undertaken by Sharma (2005, 2008), 76 who uses Eq. 6 to solve the relationship between the two 3D vectors a and b and then obtains a 3 by 3 matrix equation equivalent to Eq. 7 for one of the 3D vectors a or b. This approach provides a 3 by 3 matrix eigenvalue problem but for a more complicated matrix. The results must, of course, be the same.

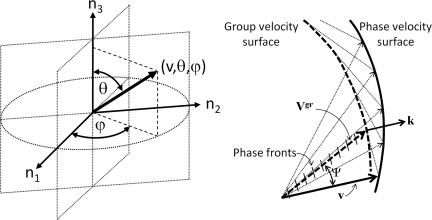

Using a spherical coordinate system, the phase velocity vector v(v, θ, ϕ) along the direction n = (sin θ cos ϕ, sin θ sin ϕ, cos θ) is expressed by the magnitude (radial distance from a fixed origin, v), its inclination angle (θ) measured from a fixed zenith direction (n3), and the azimuth angle (ϕ) of its orthogonal projection on a reference plane that passes through the origin and is orthogonal to the zenith, measured from a fixed reference direction (n1) on that plane [Fig. 1a].

Figure 1.

(a) Spherical coordinate system, where the radial distance from a fixed origin, is the magnitude of ν, θ is the inclination angle measured from a fixed zenith direction (n3), and ϕ is the azimuth angle of its orthogonal projection on a reference plane that passes through the origin and is orthogonal to the zenith, measured from a fixed reference direction (n1) on that plane. (b) Phase (v) and group (Vgr) wave velocities of quasi-waves propagating in a dispersive anisotropic medium, exhibiting different magnitude and direction ψ.

Group velocity and ray direction

Plane waves in an anisotropic medium generally travel as a waveform containing two or more waves with slightly different ω and k

| (22) |

where the term 2 cos{(ω+δω∕2)t−(k + δk∕2)} corresponds to the carrier wave, and the term cos(t δω∕2 − x δk∕2) represents the modulation envelope of the waveform. The propagation velocity of the carrier is the phase velocity,

| (23) |

and the propagation velocity of the modulation envelope is the group velocity (Auld, 1973),

| (24) |

For the 3D case, the modulation envelope or group velocity is given in spherical coordinates by

| (25) |

where the two angular components of the group velocity in Eq. 25 can be obtained by differentiation of the dispersion equation 7

| (26) |

and the rectangular components of group velocity () are given by

| (27) |

Therefore, the magnitude for the group velocity for each wave mode is

| (28) |

and the ray (energy) direction (θgr, ϕgr) is obtained as

| (29) |

Thus, the group velocity propagates along a ray at an angle to the phase propagation direction (, ) for each mode of wave propagation (m = qP1, qP2, qS1, qS2). Different phase and group velocities may exist for each of the qP1, qP2, qS1, and qS2 wave modes. In isotropic, non-dispersive media, the phase and group velocities are the same. However, phase and group velocities may be different due to dispersion or anisotropy or both. The wave vector (k) magnitude is proportional to the ratio of the frequency and the wave phase velocity, and its direction is perpendicular to the wavefront. If the difference between the phase and group velocities depends only on the magnitude of k, the difference Vgr−v is caused by dispersion. In a dispersive medium, the phase and group velocities have the same direction but different magnitudes. If the difference between phase and group velocities depends only on the direction of k, the difference Vgr − v is caused by anisotropy [Fig. 1b]. The magnitude and direction of phase and group velocities are both different in dispersive anisotropic media. In this case, the phase velocity is the projection of the velocity of energy transport in the direction of the wave normal [Fig. 1b]. The phase and group velocities are thus characterized by the phase direction (θ, ϕ) and ray direction (θgr, ϕgr), respectively. The difference between phase and ray directions is shown in Fig. 1b by the angle ψ. Anisotropy and dispersion may co-exist in biological tissues such as cancellous bone.

Attenuation coefficient

The ultrasonic attenuation coefficient αm represents the amount of energy absorption lost by the ultrasonic beam during its propagation through the medium along a path of length l for each wave mode (m = qP1, qP2, qS1, qS2). In porous media, the solution of the poroelastic Christoffel equation 17 gives complex roots since absorption is considered in the model. The complex wave number (5) defines the attenuation coefficient α for the corresponding wave mode

| (30) |

and

| (31) |

The factor −20 log(e) in the last expression is a constant that represents −20 times the base-10 logarithm of Euler’s number e and is used to translate the attenuation from nepers into decibels. It is important to notice that the attenuation of each wave mode depends on the frequency ω and the direction of propagation via the dependence of νRe and νIm in the angles θ and ϕ.

RESULTS

Numerical example

The anisotropic poroelastic model of wave propagation is now applied to the case of cancellous bone using the values of the fluid and solid constituents of bone obtained from the literature, summarized in Table TABLE I., and for 0.5 and 1.6 MHz frequency of wave propagation, accordingly to frequency values used in our previous experimental measurements (Cardoso et al., 2003).

TABLE I.

Material properties of bone used in the theoretical model.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass density of the fluid | ρf | 1000 | Kg∕m3 |

| Fluid bulk modulus | Kf | 2.25 | GPa |

| Fluid viscosity | μ | 1 × 10−3 | Pa s |

| Young’s elastic modulus the solid | Es | 18 (Turner et al., 1999; Jorgensen and Kundu, 2002; Rho et al., 1997, 1999, 71; Roy et al., 1999; Zysset et al., 1999; Hoffler et al., 2000a, Hoffler et al., 2000b; Hengsberger et al., 2001, 2002, 36; Pakula et al., 2008) | GPa |

| Shear modulus of the solid | G | 7.2 | GPa |

| Poisson ratio | ν | 0.25 | |

| Mass density of the solid | ρs | 2000 (Ashman and Rho, 1988; Nicholson et al., 1997; Morgan et al., 2003; Pakula et al., 2008) | Kg∕m3 |

| Porosity | φ | 80 | % |

| Frequency | f | 0.5, 1.6, and 2.25 | MHz |

| Fabric tensor | F | Isotropy case, F11 = 1∕3, F22 = 1∕3, and F33 = 1∕3; orthotropy case, F11=2∕29 9, F22=1∕13 3, and F33=4∕49 9. In both cases, trF = F11 + F22 + F33 = 1.0 | |

| Pore diameter | d | d1 = 310, d2 = 353, d3 = 400 (Parfitt et al., 1983; Rehman et al., 1994; Hildebrand et al., 1999; Glorieux et al., 2000) | μm |

| Intrinsic permeability | κ0 | k1 = 2.16 × 10−7, k2 = 2.44 × 10−7, k3 = 2.80 × 10−7 (Lim and Hong, 2000; Grimm and Williams, 1997b; Nauman et al., 1999; Kohles et al., 2001; Kohles and Roberts, 2002; Baroud et al., 2004; Beaudoin et al., 1991; Li et al., 1987; Pakula et al., 2008) | m2 |

Phase velocity and phase direction

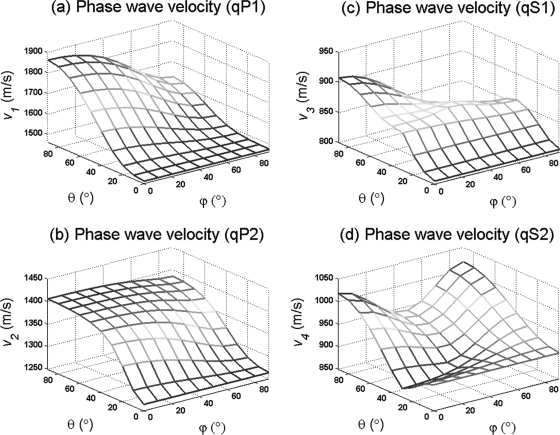

Figure 2 shows the phase velocity for the four possible wave modes generated in a porous medium as a function of phase direction (θ, ϕ) at a constant frequency in a dispersive and anisotropic medium (F11=2∕29 9, F22=1∕13 3, and F33=4∕49 9) with 83% porosity. Figure 2a shows a continuous variation on the velocity of the fast qP1 wave as a function of the inclination θ and azimuthal ϕ angles, ranging between 1470 and 1860 m∕s. The slow quasi-wave mode qP2 is shown in Fig. 2b, demonstrating a much milder variation in its velocity, with values ranging between 1260 and 1410 m∕s, always smaller than the fast qP1 wave velocities at any phase direction. The two quasi-shear wave modes qS1 and qS2 are shown in Figs. 2c, 2d, respectively. The qS1 wave has a smaller range of velocities when compared to qS2 at any analyzed phase direction (θ, ϕ). The phase velocity of each wave mode was calculated using three different frequency values, 0.5, 1.6, and 2.25 MHz, resulting in a negligible difference in phase velocity within this range of frequency.

Figure 2.

(Color online) Phase velocity as a function of phase direction (θ, ϕ) at a constant frequency for an anisotropic porous medium with 80% porosity.

Group velocity and group direction

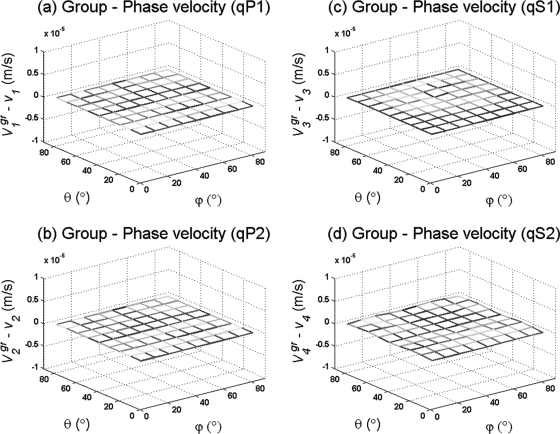

Absorption due to viscous losses generated between the solid and fluid phases of the porous medium give rise to differences between the magnitude of group and phase velocities of the several wave modes propagating in the porous medium. Generally, the effect of absorption due to dispersion is analyzed as the difference between the magnitude of group and phase velocities as a function of the frequency, along the direction of the principal axes of symmetry. In Fig. 3, we have followed a different approach by illustrating the difference in magnitude between at a constant frequency as a function of the phase direction (θ, ϕ) in an isotropic medium. The difference between group and phase velocities is shown for the quasi-fast and quasi-slow wave modes in Figs. 3a, 3b, respectively. It should be noticed that the difference is almost negligible (O 1 × 10−5 m∕s) at 0.5, 1.6, and 2.25 MHz, regardless of the phase direction being analyzed. The difference between the magnitude of the group and phase velocities for qS1 and qS2 waves is shown in Figs. 3c, 3d, respectively. The difference is equally small (O 1 × 10−5 m∕s) as for quasi-longitudinal wave modes at 0.5, 1.6, or 2.25 MHz, regardless of the phase direction (θ, ϕ). This result indicates that the group velocities of all the quasi-transverse and quasi-longitudinal wave modes are not affected by absorption processes at 0.5 − 2.25 MHz in our model.

Figure 3.

(Color online) Difference between the magnitude of group and phase velocities as a function of phase direction (θ, ϕ) at a constant frequency for an isotropic porous medium with 80% porosity.

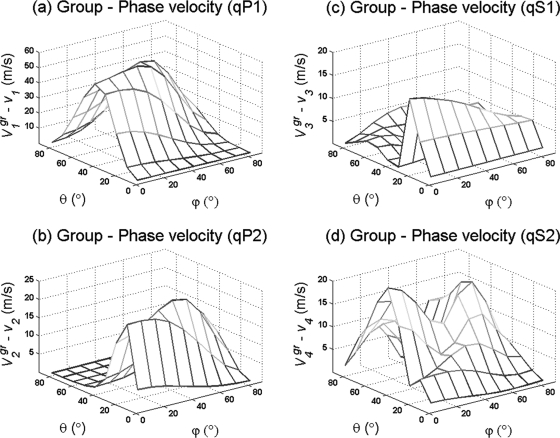

Figure 4 shows the difference in magnitude between the group and phase velocities as a function of the phase direction (ϕ, θ) in a dispersive and orthotropic medium (F11=2∕29 9, F22=1∕13 3, and F33=4∕49 9 ) as opposed to the isotropic medium (F11=1∕13 3, F22=1∕13 3, and F33=1∕13 3 ) presented in Fig. 3. The magnitude difference between group and phase velocities as a function of phase direction for the longitudinal quasi-waves varies up to 40 m∕s, and up to 10 m∕s for the quasi-shear wave modes at 83% porosity. The largest magnitude difference in is observed in the fast quasi-wave, as shown in Fig. 4a; however, this velocity difference depends on the porosity, and the slow quasi-wave mode may exhibit the largest magnitude difference between group and phase velocities at higher porosities (data not shown). It was also observed that the magnitude of the group velocity for all quasi-wave modes is always higher than the magnitude of its corresponding phase velocity.

Figure 4.

(Color online) Difference between group and phase velocities as a function of phase direction (ϕ, θ) at a constant frequency for an anisotropic porous medium with 80% porosity.

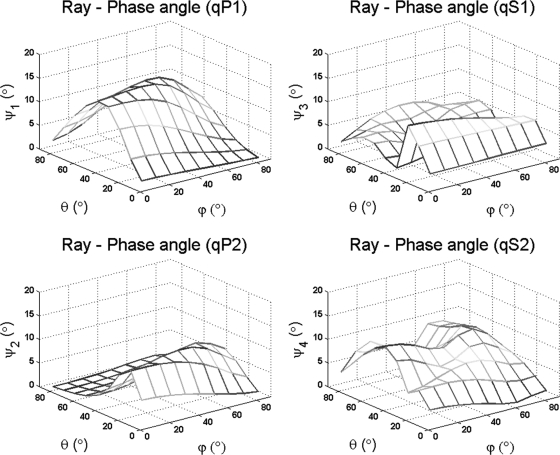

The combined results shown in Figs. 34 indicate that the magnitudes of the differences between group and phase velocities for each quasi-wave mode in a dispersive–orthotropic porous medium are different, but not in a dispersive–isotropic medium, clearly indicating the effect of the fabric anisotropy on such differences. These results also show a difference between the ray and phase (θm, ϕm) directions of each wave mode in an orthotropic medium. The difference between ray and phase directions is described by the angle ψm and is shown in Fig. 5 for all four quasi-wave modes as a function of phase direction (θm, ϕm). In this orthotropic medium with 83% porosity, the angle ψm varies by approximately 15° for the fast quasi-wave mode and 10° for the other three quasi-waves. The difference between angles ψ1 and ψ2 implies that the fast and slow quasi-wave modes propagate at slightly different directions when propagating off axes of material symmetry.

Figure 5.

(Color online) Difference between group and phase angle ψ as a function of phase direction (ϕ, θ) at a constant frequency for an anisotropic porous medium with 80% porosity.

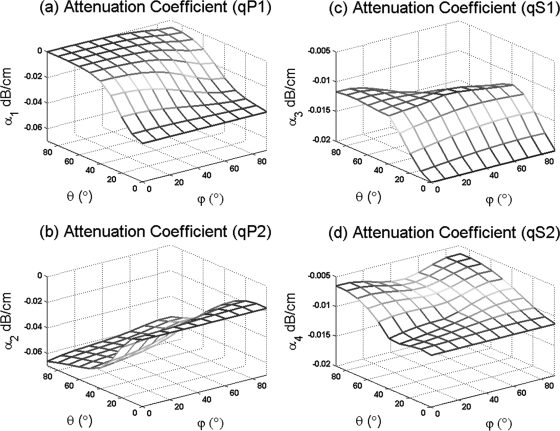

Attenuation

The attenuation of longitudinal and shear waves is generally analyzed at a given direction of wave propagation as a function of the frequency. However, that is not done here; Fig. 6 displays the dependence of the attenuation at a constant frequency as a function of the phase direction (θ, ϕ) in which the quasi-wave propagates in an orthotropic medium with 83% porosity. The attenuation exhibits small variations of the order of 1 × 10−1 to 1 × 10−2 dB∕cm for both quasi-longitudinal and quasi-shear wave modes. However, there exists a dependence of the attenuation for all four quasi-wave modes on the phase direction (θ, ϕ), indicating that the attenuation due to absorption processes in an anisotropic porous medium is dependent upon the inclination and azimuthal angles. When considering the results for the quasi-longitudinal waves qP1 and qP2 together, it can be observed that the highest attenuation for qP1 occurs at θ = 0°, and the lowest occurs at θ = 90°. The opposite, however, is shown for the qP2 wave mode, indicating that at θ = 0°, the qP1 wave has higher attenuation than qP2, but qP2 has higher attenuation than qP1 at θ = 90°. This transition in the dominating attenuation between qP1 and qP2 agrees with our previous results for pure wave modes (P1 and P2) obtained along a principal axis of fabric in an orthotropic medium (Cowin and Cardoso, 2011). This transition seems to be specific to longitudinal waves and is absent in quasi-shear waves, as shown in our numerical example, where the attenuation of qS1 is higher than the one for qS2 at any phase direction (θ, ϕ). The attenuation of quasi-wave modes was calculated using a frequency value of 0.5, 1.6, and 2.25 MHz; however, the attenuation within this range of frequency was found to be practically the same.

Figure 6.

(Color online) Attenuation coefficients as a function of phase direction (ϕ, θ) at a constant frequency in a dispersive–anisotropic porous medium with 80% porosity.

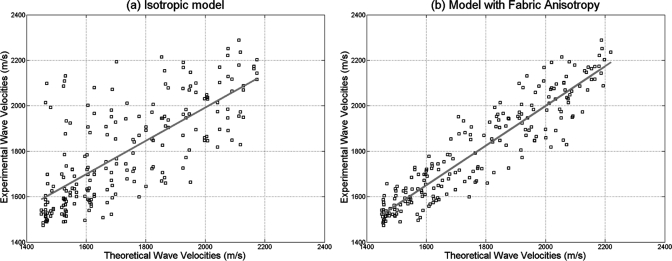

Comparison between experimental measurements and theoretical predictions

Predictions of the fast and slow wave velocities done by this model will now be compared with experimental measurements previously reported (Cardoso et al., 2003). Briefly, 14 bovine and 60 human trabecular bone samples were retrieved from bovine femoral heads, human femoral heads, and femoral and tibial condyles. Samples of approximately 1 × 1 × 1 cm in size were prepared, followed by removal of fat and marrow, and saturated with water under vacuum for 30 min. Group velocities of quasi-wave modes were measured in immersion with distillated water at room temperature, using two broadband ultrasound transducers (Panametrics V323−SU, Waltham, MA, USA) at a central frequency of 2.25 MHz (0.25 in diameter). The emitter was excited by a damped single pulse generated by an ultrasonic source (Panametrics 5052 UA, Waltham, MA, USA) operated in a transmission mode. The signal was amplified in 40 dB, digitized by a 100 MHz Digital Oscilloscope (Tektronik 2430, Beaverton, OR, USA) and analyzed in MATLAB. Importantly, bone cubes were cut without aligning its orthogonal faces with the planes of symmetry of the sample. Since bone samples were interrogated along the normal direction to each face of the sample (e.g., arbitrary directions labeled as A, B, and C), which do not coincide with the normal to the planes of symmetry of the sample, it was considered that propagated signals correspond to quasi-wave modes for each of the three interrogated directions. It was shown in that study that the wavelength of the fast and slow waves are significantly different and that this property can be used to separate the two waves using digital filtering. Therefore, acquired signals were filtered out using bandpass filters with a frequency bandwidth of 0.5 ± 0.25 MHz for the fast wave and a frequency bandwidth of 1.6 ± 0.6 MHz for the slow wave. The fabric tensor describing the microarchitecture on each sample was measured using the mean intercept length as described in Whitehouse (1974), Whitehouse and Dyson (1974), Harrigan and Mann (1984), and Turner et al. (1987, 1990), 79 The phase angles θ, ϕ were determined as the relative orientation of the principal axes of fabric in respect to the measurement directions A, B, and C of the cube samples. The porosity, pore diameter, and apparent density of the sample were obtained through analysis of bone images and weight of the sample using Archimedes principle. The intrinsic permeability was estimated on each sample using the relationship k0 = d2 (Bear, 1988). Values of the mass densities and elastic modulus of the solid and fluid phases, as well as the viscosity of the fluid, were taken from Table TABLE I..

In order to investigate the effect of fabric on the fast and slow wave velocity measurements, two cases were analyzed by comparing experimental values with theoretical predictions. First, the theoretical phase velocities for qP1 and qP2 were computed using the experimental values of porosity, tissue density, and without taking into account the fabric anisotropy, but considering the fabric as isotropic (F11 = F22 = F33 = 1∕3). Then, the ray direction and group velocity were calculated for each quasi-longitudinal mode. Figure 7a shows a comparison between the group velocities predicted from the model (under the assumption of isotropy) and the experimental wave velocity measurements obtained on three orthogonal directions on each sample. In the second case, the theoretical phase velocities for qP1 and qP2 were computed as in the previous case, but this time using the images-derived fabric anisotropy values for each sample. Again, the ray direction and group velocity were calculated for each quasi-longitudinal mode. Figure 7b shows the comparison between experimental group wave velocities, for all three directions A, B, and C and predicted wave velocity values when the fabric was taken into account. The correlation coefficient between experimental and theoretical predictions when the fabric anisotropy is not taken into account was R2 = 0.53 and when the fabric anisotropy was included in the theoretical model was R2 = 0.86. This analysis indicates a much higher quantitative agreement between experimental and theoretical values of group quasi-wave velocity when the fabric anisotropy is included in the model.

Figure 7.

(Color online) Comparison of experimental ultrasound wave velocities against theoretical model predictions when considering (a) isotropic fabric and (b) anisotropic fabric measurements. The predictability of experimental values by the poroelastic theory is much increased when the fabric anisotropy is taken into account.

DISCUSSION

A theoretical framework for analysis of wave propagation along a principal axis of fabric in an anisotropic poroelastic medium was recently developed (Cowin and Cardoso, 2011). That model was extended in this study to the case of an arbitrary phase direction (6, p) of wave propagation. The advantage of the present development is the ability to distinguish the role of fabric anisotropy in the predictions of phase and group velocities of the four wave modes propagating in porous media at any phase or ray direction.

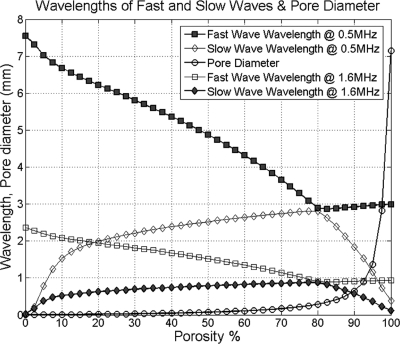

The fabric anisotropy plays a critical role in the phase and group velocity of quasi-wave modes. The results from Fig. 2 indicate that the phase velocity of quasi-wave modes is strongly dependent on the phase direction (θ, ϕ) in anisotropic porous media. This acoustic anisotropy was included into the model using the fabric tensor measurement. When the fabric tensor was isotropic, the resultant wave propagation velocities are reduced to those of an isotropic medium. Importantly, the results shown in Figs. 34 indicate that the dispersion due to the viscous friction between the solid and fluid in bone within the 0.5−2.25 MHz frequency range is practically negligible, while the difference between phase and group velocities of quasi-wave modes was due to fabric anisotropy. The effect of anisotropy on the difference between group and phase velocities was found more significant in longitudinal than in shear wave modes. However, the sensitivity of the quasi-fast or quasi-slow wave to fabric anisotropy varies according to the porosity of the medium as shown in Cowin and Cardoso (2011). Moreover, the results presented in Fig. 5 confirmed a significant difference between the phase and ray directions analyzed in anisotropic media. The results in Fig. 6 predict a dependence of the attenuation for all four quasi-wave modes on the phase direction (θ, ϕ) at 0.5−2.25 MHz. However, this attenuation predicted is very small when compared to experimental values reported in the literature (Haïat et al., 2006; Sasso et al., 2008; Pakula et al., 2009). This result indicates that the role of absorption and anisotropy on the attenuation of quasi-wave modes is minimal and cannot explain the experimental attenuation recorded in those experimental studies. The possible mechanism explaining such measurements is likely to be scattering of waves, for which the fabric dependence would need to be developed. It is also important to notice that the wavelengths generated in the porous medium by waves traveling at any given frequency should be larger than the pore diameter (the inhomogeneity) in the porous medium. Otherwise, the applicability of the theory cannot be guaranteed. Figure 8 shows the comparison between the size of the wavelength of the fast and slow waves generated at either 0.5 or 1.6 MHz and the size of the pore diameter (the inhomogeneity of the pore medium). In this figure, it can be seen that the wavelength of the fast wave at 0.5 MHz is larger than the pore diameter from 0% to 97% porosity, and that the wavelength of the slow wave is larger than the pore diameter from 0% to 90% porosity, when the 1.6 MHz frequency is used. The pore diameter vs porosity relationship was previously introduced (Cowin and Cardoso, 2011) based on histomorphometrical studies on cancellous bone that have reported pore sizes (trabecular spacing) ranging from 300 to 2200 μm for samples between 52% and 96% porosity (Parfitt et al., 1983; Rehman et al., 1994; Hildebrand et al., 1999; Glorieux et al., 2000). Furthermore, the pore size in 5% − 10% porosity cortical bone tissue is considered to vary around 20 to 60 μm, which corresponds to the pore size of Haversian canals (Jones et al., 2004; Basillais et al., 2007).

Figure 8.

Comparison between the size of the wavelength of the fast and slow waves generated at 0.5 and 1.6 MHz, respectively, and the size of the pore diameter (porous medium inhomogeneity). The wavelength of the fast wave at 0.5 MHz (solid squares) is larger than the pore diameter from 0% to 97% porosity, and that the wavelength of the slow wave at 1.6 MHz (solid diamonds) is larger than the pore diameter (circles) from 0% to 90% porosity, when this 1.6 MHz frequency is used. For comparison, we also included in this figure the wavelengths of the fast wave at 1.6 MHz (empty diamonds) and the wavelengths of the slow wave at 0.5 MHz (empty squares).

The comparison between experiments and theoretical predictions was performed in samples that were not cut aligned to their planes of symmetry. Therefore, the measured waves on those samples are not pure wave modes but quasi-waves. The development of the fabric-dependent anisotropic theory of propagation of quasi-waves in porous media was presented in this study, and a quantitative analysis of these experimental results was performed. The theoretical model was able to predict the high variability of fast and slow wave velocities observed in bovine and human bone in our experimental study. Figure 7 indicates that the fabric tensor measurement alone is able to drastically increase the model predictability on wave velocities from 53% to 86%. In other words, directional variability within a sample was effectively explained by the theoretical model after inclusion of the fabric; this directional variability could not be explained by the porosity only. The agreement between experimental and theoretical values indicates that despite the complexity added to the poroelastic theory, a tensorial variable describing the bone microstructure is required to explain the directional variability of the wave propagation with bone architecture. Therefore, the fabric tensor—a measure of bone microarchitecture—exhibited a role as important as the mass density in determining the acoustic properties of anisotropic porous bone samples.

A major goal of ultrasound wave propagation measurements is to determine non-invasively the elastic constants of the porous medium using an inverse problem approach. However, measurements of wave velocities in anisotropic–dispersive media correspond to the group velocities of each wave mode, not to the phase velocities. The latter are, in fact, directly related to the elastic constants of the porous medium. Therefore, it is necessary to better understand the mechanisms (absorption and anisotropy) that are at the origin of differences between phase and group velocities in a porous medium. The analysis presented in this study allowed identifying fabric anisotropy, and not the solid–fluid viscous losses, as the dominating factor affecting the difference between phase and group velocities in anisotropic–dispersive porous media at high frequencies (0.5 – 1.6 MHz). The opposite may happen, however, at low frequencies (Hz to KHz range). Importantly, this study suggests that the distinction between group velocity and phase velocity is important when the estimation of anisotropic elastic constants in a porous medium is sought. Moreover, it indicates the possibility of using such variations between phase and group velocities as a function of the phase direction (θ, ϕ) to estimate the fabric tensor in porous media using ultrasound.

Ultrasound wave propagation is sensitive to directional changes in microarchitecture of porous media. Unfortunately, most clinical ultrasound densitometers perform their measurements in a single direction, not taking advantage of the ability of ultrasound to distinguish microarchitecture anisotropy. This has also been a consequence of the lack of anisotropic theoretical models of wave propagation permitting to describe the wave velocity variability in anisotropic cancellous bone. The proposed approach provides a rigorous theoretical framework to interpret and analyze measurements of wave velocities in porous media along a general direction. Efforts in clinical ultrasound, which are made toward developing experimental approaches to measure ultrasound wave propagation in multiple directions at appropriate skeletal sites, such as the wrist or the femur, major sites of osteoporosis-related fractures, may benefit of this anisotropic poroelastic wave propagation theory.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (AG34198 & HL069537-07 R25 Grant for Minority BME Education), the National Science Foundation (NSF 0723027, PHY-0848491), and the PSC-CUNY Research Award Program of the City University of New York.

APPENDIX

Tensors Q, C, and S are expressed as a function of the general direction of wave propagation n

| (A1) |

where

| (A2) |

| (A3) |

| (A4) |

where the constant M was previously defined in Eq. 3,

| (A5) |

References

- Anderson, C. C., Marutyan, K. R., Holland, M. R., Wear, K. A., and Miller, J. G. (2008). “Interference between wave modes may contribute to the apparent negative dispersion observed in cancellous bone,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 124, 1781–1789. 10.1121/1.2953309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C. C., Pakula, M., Holland, M. R., Bretthorst, G. L., Laugier, P., and Miller, J. G. (2009). “Extracting fast and slow wave velocities and attenuations from experimental measurements of cancellous bone using Bayesian probability theory,” Proc.-IEEE Ultrason. Symp. 546–549. [Google Scholar]

- Ashman, R. B., and Rho, J. Y. (1988). “Elastic modulus of trabecular bone material,” J. Biomech. 21, 77–181. 10.1016/0021-9290(88)90167-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auld, B. (1973). Acoustic Fields and Waves in Solids, Vol. 1 (John Wiley and Sons, New York: ), 435 p. [Google Scholar]

- Baroud, G., Falk, R., Crookshank, M., Sponagel S., and Steffen, T. (2004). “Experimental and theoretical investigation of directional permeability of human vertebral cancellous bone for cement infiltration,” J. Biomech. 37, 189–196. 10.1016/S0021-9290(03)00246-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basillais, A., Bensamoun, S., Chappard, Ch., Brunet-Imbault, B., Lemineur, G., Ilharreborde, B., Ho Ba Tho, M. C., Benhamou, C. L. (2007). “Three-dimensional characterization of cortical bone microstructure by microcomputed tomography: Validation with ultrasonic and microscopic measurements,” J. Orthop. Sci. 12(2), 141–148. 10.1007/s00776-006-1104-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bear, J. “Dynamics of Fluids in Porous Media,” (Dover Publications, New York). [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin, A. J., Mihalko, W. M., and Krause, W. R. (1991). “Finite element modelling of polymethylmethacrylate flow through cancellous bone,” J. Biomech. 24(2), 127–136. 10.1016/0021-9290(91)90357-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biot, M. A. (1941). “General theory of three-dimensional consolidation,” J. Appl. Phys. 12, 155–164. 10.1063/1.1712886 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biot, M. A. (1955). “Theory of elasticity and consolidation for a porous anisotropic solid,” J. Appl. Phys. 26, 182. 10.1063/1.1721956 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biot, M. A. (1956a). “Theory of propagation of elastic waves in a fluid saturated porous solid I low frequency range,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 28, 168–178. 10.1121/1.1908239 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biot, M. A. (1956b). “Theory of propagation of elastic waves in a fluid saturated porous solid II higher frequency range,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 28, 179–191. 10.1121/1.1908241 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biot, M. A. (1962a). “Mechanics of deformation and acoustic propagation in porous media,” J. Appl. Phys. 33, 1482–1498. 10.1063/1.1728759 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biot, M. A. (1962b). “Generalized theory of acoustic propagation in porous dissipative media,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 28, 1254–1264. 10.1121/1.1918315 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, L., Meunier, A., and Oddou, C. (2008). “In vitro acoustic wave propagation in human and bovine cancellous bone as predicted by the Boit’s theory,” J. Mech. Med. Biol. 8(2), 1–19. 10.1142/S0219519408002565 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, L., Teboul, F., Meunier, A., and Oddou, C., (2001). “Ultrasound characterization of cancellous bone: Theoretical and experimental analysis,” Trans. Ultrason. Symp. IEEE 2, 1213–1216. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, L., Teboul, F., Sedel, L., Meunier, A., and Oddou, C. (2003). “In vitro acoustic waves propagation in human and bovine cancellous bone,” J. Bone Miner. Res. 18(10), 1803–1812. 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.10.1803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowin, S. C. (1985). “The relationship between the elasticity tensor and the fabric tensor,” Mech. Mater. 4, 137–147. 10.1016/0167-6636(85)90012-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cowin, S. C. (1986). “Wolff’s law of trabecular architecture at remodeling equilibrium,” J. Biomech. Eng. 108, 83–88. 10.1115/1.3138584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowin, S. C. (1997). “Remarks on the paper entitled ‘Fabric and elastic principal directions of cancellous bone are closely related’,” J. Biomech. 30, 1191–1192. 10.1016/S0021-9290(97)85609-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowin, S. C. (1999). “Bone poroelasticity,” J. Biomech. 32, 218–238. 10.1016/S0021-9290(98)00161-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowin, S. C. (2004). “Anisotropic poroelasticity: Fabric tensor formulation,” Mech. Mater. 36, 665–677. 10.1016/j.mechmat.2003.05.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cowin, S. C., and Cardoso, L. (2011). “Fabric dependence of poroelastic wave propagation,” Biomech. Model Mechanobiol. 10(1), 39–65. 10.1007/s10237-010-0217-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowin, S. C., and Mehrabadi M. M., (2007). “Compressible and incompressible constituents in anisotropic poroelasticity: The problem of unconfined compression of a disk,” J. Mech. Phys. Solids 55, 161–193. 10.1016/j.jmps.2006.04.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cowin, S. C., and Satake, M. (1978). “Continuum Mechanical and Statistical Approaches in the Mechanics of Granular Materials.” Proceedings of the U.S.-Japan Seminar on Continuum Mechanical and Statistical Approaches in the Mechanics of Granular Materials, edited by Stephen C. Cowin and Masao Satake, Gakujutsu Bunken Fukyu-Kai, Tokyo, 350 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Ericksen, J. L. (1960). “Tensor fields” in Encyclopedia of Physics, edited by Truesdell C. A. (Springer, Berlin, Germany: ), pp. 794–858. [Google Scholar]

- Fellah, Z. E. A., Chapelon, J. Y., Berger, S., Lauriks, W., and Depollier, C. (2004). “Ultrasonic wave propagation in human cancellous bone: Application of Biot theory,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 116, 61–73. 10.1121/1.1755239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellah, Z. A., Sebaa, N., Fellah, M., Mitri, F. G., Ogam, E., Lauriks, W., Depollier, C. (2008). “Application of the biot model to ultrasound in bone: direct problem,” IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control 55, 1508–15. 10.1109/TUFFC.2008.826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glorieux, F. H, Travers, R., Taylor, A., Bowen, J. R., Rauch, F., Norman, M., and Parfitt, A. M. (2000). “Normative data for iliac bone histomorphometry in growing children,” Bone 26, 103–109. 10.1016/S8756-3282(99)00257-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigorian, M., Shepherd, J. A., Cheng, X. G., Njeh, C. F., Toschke, J. O., and Genant, H. K. (2002). “Does osteoporosis classification using heel BMD agree across manufacturers?” Osteoporos Int. 13, 613–7. 10.1007/s001980200082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm, M. J., and Williams, J. L. (1997a). “Assessment of bone quantity and ‘quality’ by ultrasound attenuation and velocity in the heel,” Clin. Biomech. (Bristol, Avon; ) 12, 281–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm, M. J., and Williams, J. L. (1997b). “Measurements of permeability in human calcaneal trabecular bone,” J. Biomech. 30, 743–745. 10.1016/S0021-9290(97)00016-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haïat, G., Padilla, F., Cleveland, R. O., and Laugier, P. (2006). “Effects of frequency-dependent attenuation and velocity dispersion on in vitro ultrasound velocity measurements in intact human femur specimens,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 53, 39–51. 10.1109/TUFFC.2006.1588390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haire, T. J, and Langton, C. M. (1999). “Biot theory: A review of its application to ultrasound propagation through cancellous bone,” Bone 24, 291–295. 10.1016/S8756-3282(99)00011-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hans, D., Fuerst, T., and Uffmann, M. (1996). “Bone density and quality measurement using ultrasound,” Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 8, 370–375. 10.1097/00002281-199607000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrigan, T., and Mann, R. W. (1984). “Characterization of microstructural anisotropy in orthotropic materials using a second rank tensor,” J. Mat. Sci. 19, 761–769. 10.1007/BF00540446 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hengsberger, S., Kulik, A., and Zysset, P. (2001). “A combined atomic force microscopy and nanoindentation technique to investigate the elastic properties of bone structural units,” Eur. Cell.sMater. 1, 12–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengsberger, S., Kulik A., and Zysset, P., (2002). “Nanoindentation discriminates the elastic properties of individual human bone lamellae under dry and physiological conditions,” Bone 30, 178–184. 10.1016/S8756-3282(01)00624-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand, T., Laib, A., Miiller, R., Dequeker, J., and Riiegsegger, P. (1999). “Direct three-dimensional morphometric analysis of human cancellous bone: Microstructural data from spine, femur, iliac crest, and calcaneus,” J. Bone Miner. Res. 14, 1167–1174. 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.7.1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard, J. E. (1967). “Determination of structural anisotropy,” in Stereology, Proceedings of the 2nd International Congress for Stereology, Chicago, IL (Springer, Berlin, Germany: ), 219 p. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffler, C. E., Moore, K. E., Kozloff, K., Zysset, P. K., and Goldstein, S. A. (2000a). “Age, gender, and bone lamellae elastic moduli,” J. Orthop. Res. 18, 432–437. 10.1002/jor.v18:3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffler, C. E., Moore, K. E., Kozloff, K., Zysset, P. K., Brown, M. B., and Goldstein, S. A. (2000b). “Heterogeneity of bone lamellar-level elastic moduli,” Bone 26, 603–609. 10.1016/S8756-3282(00)00268-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa, A., and Otani, T. (1997). “Ultrasonic wave propagation in bovine cancellous bone,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 101, 558–562. 10.1121/1.418118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa, A., and Otani, T. (1998). “Acoustic anisotropy in bovine cancellous bone,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 103, 2718–2722. 10.1121/1.422790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D. L. Koplik, J., and Dashen, R., (1987). “Theory of dynamic permeability and tortuosity in fluid-saturated porous media,” J. Fluid Mech. 176, 379–402. 10.1017/S0022112087000727 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A. C, Sheppard, A. P., Sok, R. M., Arns, C. H., Limaye, A., Averdunk, H., Brandwood, A., Sakellariou, A., Senden, T. J., Milthorpe, B. K., and Knackstedt, M. A. (2004). Three-dimensional analysis of cortical bone structure using X-ray micro-computed tomography. Physica A 339, 125–130, 10.1016/j.physa.2004.03.046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Proceedings of the International Conference New Materials and Complexity.

- Jorgensen, C. S., and Kundu, T. (2002). “Measurement of material elastic constants of trabecular bone: A micromechanical analytic study using a 1 GHz acoustic microscope,” J. Orthop. Res. 20, 151–158. 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00061-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek, M., Kubik, J., and Pakula, M. (2002). “Short ultrasonic waves in cancellous bone,” Ultrasonics 40, 95–100. 10.1016/S0041-624X(02)00097-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanatani, K. (1983). “Characterization of structural anisotropy by fabric tensors and their statistical test,” J. Jpn Soil Mech. Found. Eng. 23, 171. [Google Scholar]

- Kanatani, K. (1984a). “Distribution of directional data and fabric tensors,” Int. J. Eng. Sci. 22, 149–164. 10.1016/0020-7225(84)90055-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanatani, K. (1984b). “Stereological determination of structural anisotropy,” Int. J. Eng. Sci. 22, 531–546. 10.1016/0020-7225(84)90055-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanatani, K. (1985). “Procedures for stereological estimation of structural anisotropy,” Int. J. Eng. Sci. 23, 587–596. 10.1016/0020-7225(85)90067-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kohles, S. S., and Roberts, J. B. (2002). “Linear poroelastic cancellous bone anisotropy: Trabecular solid elastic and fluid transport properties,” J. Biomech. Eng. 124, 521–526. 10.1115/1.1503374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohles, S. S., Roberts, J. B., Upton, M. L., Wilson, C. G., Bonassar, L. J., and Schlichting, A. L. (2001). “Direct perfusion measurements of cancellous bone anisotropic permeability,” J. Biomech. 34, 1197–1202. 10.1016/S0021-9290(01)00082-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, G. P, Bronk, J. T, An, K. N, and Kelly, P. J. (1987). “Permeability of cortical bone of canine tibiae,” Microvasc. Res. 34, 302–310. 10.1016/0026-2862(87)90063-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, T. H., and Hong, J. H. (2000). “Poroelastic properties of bovine vertebral trabecular bone,” J. Orthop. Res. 18, 671–677. 10.1002/jor.v18:4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W., Xia, Y., and Qin, Y. X. (2009). “Characterization of the trabecular bone structure using frequency modulated ultrasound pulse,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 125, 4071–4077. 10.1121/1.3126993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura, M., Eckstein, F., Lochmiller, E.-M., and Zysset, P. K. (2008). “The role of fabric in the quasi-static compressive mechanical properties of human trabecular bone from various anatomical locations,” Biomech. Model Mechanobiol. 7, 27–42. 10.1007/s10237-006-0073-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, K., Matsukawa, M., Otani, T., Takada, M., Mano, I., and Tsujimoto, T. (2008). “Effects of structural anisotropy of cancellous bone on speed of ultrasonic fast waves in the bovine femur,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 55, 1480–1477. 10.1109/TUFFC.2008.823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, K., Matsukawa, M., Otani, T., Laugier, P., and Padilla, F. (2009). “Propagation of two longitudinal waves in human cancellous bone an in vitro study,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 125, 3460–3466. 10.1121/1.3111107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, E. F., Bayraktar, H. H., and Keaveny, T. M. (2003). “Trabecular bone modulus-density relationships depend on anatomic site,” J. Biomech. 36, 897–904. 10.1016/S0021-9290(03)00071-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauman, E. A., Fong, K. E., and Keaveny, T. M. (1999). “Dependence of intertrabecular permeability on flow direction and anatomic site,” Ann. Biomed. Eng. 27, 517–524. 10.1114/1.195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, V. H., Naili, S, and Sansalone, V. (2010). “Simulation of ultrasonic wave propagation in anisotropic cancellous bone immersed in fluid,” Wave Motion, 47(2), 117–129. 10.1016/j.wavemoti.2009.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, P. H., Cheng, X. G., Lowet, G., Boonen, S., Davie, M. W., Dequeker, J., and Van der Perre, G. (1997). “Structural and material mechanical properties of human vertebral cancellous bone,” Med. Eng. Phys. 19, 729–737. 10.1016/S1350-4533(97)00030-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odgaard, A. (1997). “Three-dimensional methods for quantification of cancellous bone architecture,” Bone 20, 315–328. 10.1016/S8756-3282(97)00007-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odgaard, A. (2001). “Quantification of cancellous bone architecture,” in Bone Mechanics Handbook, edited by Cowin S.C. (CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL: ), pp. 14–19: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Odgaard, A., Kabel, J., van Rietbergen, B., Dalstra, M., and Huiskes, R. (1997). “Fabric and elastic principal directions of cancellous bone are closely related.” J. Biomech. 30, 487–495. 10.1016/S0021-9290(96)00177-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakula, M., Padilla, F., Laugier, P., Kaczmarek, M. (2008). “Application of Biot’s theory to ultrasonic characterization of human cancellous bones: determination of structural, material, and mechanical properties,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 123, 2415–2423. 10.1121/1.2839016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakula, M., Padilla, F., and Laugier, P. (2009). “Influence of the filling fluid on frequency-dependent velocity and attenuation in cancellous bones between 0.35 and 2.5 MHz,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 126, 3301–3310. 10.1121/1.3257233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parfitt, A. M., Mathews, C. H., Villanueva, A. R., Kleerekoper, M., Frame, B., and Rao, D. S. (1983). “Relationships between surface, volume, and thickness of iliac trabecular bone in aging and in osteoporosis. Implications for the microanatomic and cellular mechanisms of bone loss,” J. Clin. Invest. 72, 1396–1409. 10.1172/JCI111096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, M. T., Hoyland, J. A., Denton, J., and Freemont, A. J. (1994). “Age related histomorphometric changes in bone in normal British men and women.” J. Clin. Pathol. 47, 529–534. 10.1136/jcp.47.6.529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rho, J. Y., Roy, M. E. 2nd, Tsui, T. Y., and Pharr, G. M. (1999). “Elastic properties of microstructural components of human bone tissue as measured by nanoindentation,” J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 45, 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy, M. E., Rho, J. Y., Tsui, T. Y., Evans N. D., and Pharr, G. M. (1999). “Mechanical and morphological variation of the human lumbar vertebral cortical and trabecular bone,” J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 44, 191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rho, J. Y., Tsui T. Y., and Pharr, G. M. (1997). “Elastic properties of human cortical and trabecular lamellar bone measured by nanoindentation,” Biomaterials 18, 1325–1330. 10.1016/S0142-9612(97)00073-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata, S., Barkmann, R., Lochmuller, E. M., Heller, M., and Gluer, C. C. (2004). “Assessing bone status beyond BMD: Evaluation of bone geometry and porosity by quantitative ultrasound of human finger phalanges,” J. Bone Miner. Res. 19, 924–930. 10.1359/JBMR.040131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasso, M., Haïat, G., Yamato, Y., Naili, S., and Matsukawa, M. (2008). “Dependence of ultrasonic attenuation on bone mass and microstructure in bovine cortical bone,” J. Biomech. 41, 347–355. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satake, M. (1982). “Fabric tensor in granular materials,” in Deformation and Failure of Granular Materials, edited by Vermeer P.A. and Lugar (Balkema H. J., Rotterdam, the Netherlands: ), p. 63. [Google Scholar]

- Sebaa, N., Fellah, Z. A., Fellah, M., Ogam, E., Mitri, F. G., Depollier, C., Lauriks, W. (2008). “Application of the Biot model to ultrasound in bone: inverse problem,” IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control 55, 1516–1523. 10.1109/TUFFC.2008.827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, M. D. (2005). “Propagation of inhomogeneous plane waves in dissipative anisotropic poroelastic solids,” Geophys. J. Int. 163, 981–990. 10.1111/j.1365-246X.2005.02701.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, M. D. (2008). “Propagation of harmonic plane waves in a general anisotropic porous solid,” Geophys. J. Int. 172(3), 982–994. 10.1111/j.1365-246X.2007.03659.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siffert, R., and Kaufman J. (2006). “Ultrasonic bone assessment ‘The time has come’,” Bone 40(1), 5. 10.1016/j.bone.2006.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner, C. H., and Cowin, S. C. (1987). “On the dependence of the elastic constants of an anisotropic porous material upon porosity and fabric,” J. Mater. Sci. 22, 3178–3184. 10.1007/BF01161180 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner, C. H., Cowin, S. C., Rho J. Y., Ashman, R. B., and Rice, J. C. (1990). “The fabric dependence of the orthotropic elastic properties of cancellous bone,” J. Biomech. 23, 549–561. 10.1016/0021-9290(90)90048-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner, C. H., Rho, J., Takano. Y., Tsui, T. Y., and Pharr, G. M. (1999). “The elastic properties of trabecular and cortical bone tissues are similar: Results from two microscopic measurement techniques,” J. Biomech. 32, 437–441. 10.1016/S0021-9290(98)00177-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rietbergen, B., Odgaard, A., Kabel, J., and Huiskes, R. (1996). “Direct mechanics assessment of elastic symmetries and properties of trabecular bone architecture,” J. Biomech. 29, 1653–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rietbergen, B., Odgaard, A., Kabel, J. and Huiskes, R., (1998). “Relationships between bone morphology and bone elastic properties can be accurately quantified using high-resolution computer reconstructions,” J. Orthop. Res., 16, 23–28. 10.1002/jor.v16:1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wear, K. A. (2009). “Frequency dependence of average phase shift from human calcaneus in vitro,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 126, 3291–3300. 10.1121/1.3257550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wear, K. A. (2010). “Decomposition of two-component ultrasound pulses in cancellous bone using modified least squares Prony method—Phantom experiment and simulation,” Ultrasound Med Biol. 36, 276–287. 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2009.06.1092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wear, K. A., Laib, A., Stuber, A. P., and Reynolds, J. C. (2005). “Comparison of measurements of phase velocity in human calcaneus to Biot theory,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 117(5), 3319–3324. 10.1121/1.1886388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse, W. J. (1974). “The quantitative morphology of anisotropic trabecular bone,” J. Microsc. 101, 153–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse, W. J., and Dyson, E. D. (1974). “Scanning electron microscope studies of trabecular bone in the proximal end of the human femur,” J. Anat. 118, 417–444. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J. L. (1992). “Ultrasonic wave propagation in cancellous and cortical bone: Prediction of some experimental results by Biot’s theory,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 91, 1106–1112. 10.1121/1.402637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y., Lin, W., Qin, Y. X. (2007). “Bone surface topology mapping and its role in trabecular bone quality assessment using scanning confocal ultrasound,” Osteoporos Int. 18(7), 905–913. 10.1007/s00198-007-0324-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zysset, P. K., Guo, X. E., Hoffler, C. E., Moore, K. E., and Goldstein, S.A. (1999). “Elastic modulus and hardness of cortical and trabecular bone lamellae measured by nanoindentation in the human femur,” J. Biomech. 32, 1005–1012. 10.1016/S0021-9290(99)00111-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]