Abstract

Our work on atrophic remodelling of the heart has led us to appreciate the simple principles in biology: (i) the dynamic nature of intracellular protein turnover, (ii) the return to the foetal gene programme when the heart remodels, and (iii) the adaptive changes of cardiac metabolism. Although the molecular mechanisms of cardiac hypertrophy are many, much less is known regarding the molecular mechanisms of cardiac atrophy. We state the case that knowing more about mechanisms of atrophic remodelling may provide insights into cellular consequences of metabolic and haemodynamic unloading of the stressed heart. Overall we strive to find an answer to the question: ‘What makes the failing heart shrink and become stronger?' We speculate that signals arising from intermediary metabolism of energy-providing substrates are likely candidates.

Keywords: Cardiac atrophy, Mechanical unloading, Metabolic unloading

1. Introduction

Dr William Boswell Castle, the famous Harvard haematologist, once said, ‘In all ages the time available in which to think has probably been largely wasted by most.'1 As we set out to review the complex field of atrophic remodelling of the normal and failing heart, we were reminded of his admonition. It is our aim to present the reader with a conceptual frame work that accommodates both metabolic and structural remodelling of the heart in response to a decrease in its load.

2. The big picture

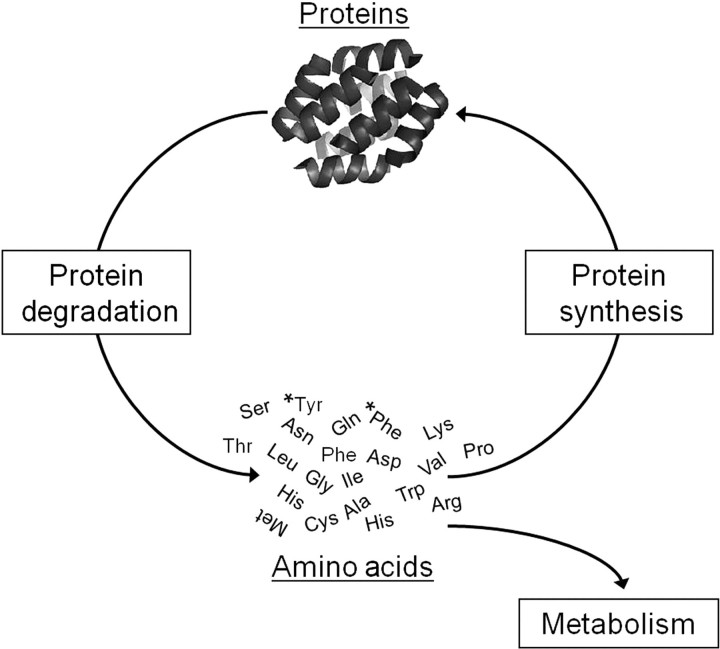

Our work on atrophic remodelling of the heart2 has led us to appreciate two simple principles in biology: First, from the cell cycle to the Krebs cycle, there is no life without cycles. The same principle applies to the cycle of intracellular protein synthesis and degradation (Figure 1). Although cellular regeneration of the heart now receives much attention,3 it is almost overlooked that each cardiomyocyte renews itself. This is surprising, because, while stem cells contribute to the replacement of cardiomyocytes after injury, they contribute little to cardiomyocyte renewal during normal ageing.4 Although the dynamic state of body constituents is known since the 1940s, the idea that heart muscle cells continuously renew themselves from within and in response to environmental stimuli (such as metabolic and/or hemodynamic stress) is relatively new.5–7 Second, and equally important, we learned that remodelling of the cardiomyocyte results in a return to the foetal gene programme, no matter whether the heart hypertrophies or atrophies (Table 1) or whether the heart is exposed to the metabolic milieu of diabetes.8–10 Contrary to our original speculation that the failing human heart reverts to the foetal gene programme after mechanical unloading,2 we observed that the foetal gene programme is already activated in the failing human heart.11 Mechanical unloading of the failing heart does not restore the transcript levels of metabolic genes with the notable exception of uncoupling protein 3 (UCP3).12 The perplexing question remains: how does the heart shrink and become stronger (i.e. haemodynamically stronger which is measurable by increased contractile force)? This process seems counterintuitive because atrophied skeletal muscle is always associated with a decrease in contractile strength. In the following sections, we will discuss selected aspects of metabolic and haemodynamic loading and unloading as they relate to atrophic remodelling in both the normal and the stressed heart. Table 2 summarizes the topics we will discuss in our effort to define the complexities of atrophic remodelling of the heart. Because the substrate for atrophic remodelling most often involves a stressed heart, a brief consideration of metabolic and haemodynamic stresses is in order.

Figure 1.

Protein turnover in the heart. The balance of protein synthesis and degradation determines size and function of cardiomyocytes. Damaged, misfolded, or useless proteins are degraded to amino acids which are used for the synthesis of new, functional proteins. The amino acids phenylalanine and tyrosine (*Phe, *Tyr) are not metabolized by heart muscle and therefore used as tracers for protein synthesis and degradation in pulse-chase experiments.

Table 1.

Transcriptional signatures of atrophy and hypertrophy are the same

| Hypertrophy | Atrophy | |

|---|---|---|

| Proto-oncogenes | ||

| c-fos | ↑ | ↑ |

| c-myc | ↑ | ↑ |

| Atrial natiuretic factor | ↑ | ↑ |

| Growth factors | ||

| TGFβ1 | ↑ | = |

| TGFβ2 | ↑ | ↑ |

| Transcription factors | ||

| MEF-2A | = | = |

| MEF-2C | = | = |

| GATA4 | = | = |

| Sarcomeric proteins | ||

| α-MHC | ↓ | ↓ |

| β-MHC | ↑ | ↑ |

| Cardiac α-actin | ↓ | ↓ |

| Skeletal α-actin | ↑ | ↑ |

| Ion pumps | ||

| α2 Na/K-ATPase | ↓ | ↓ |

| SERCA 2a | ↓ | ↓ |

| Metabolic proteins | ||

| GLUT1 | = | = |

| GLUT4 | ↓ | ↓ |

| Muscle CPT-1 | ↓ | ↓ |

| Liver CPT-1 | = | = |

| Mitochondrial CK | ↓ | ↓ |

| PPARα | ↓ | ↓ |

| PDK4 | ↓ | ↓ |

| MCD | ↓ | ↓ |

| UCP2 | ↓ | ↓ |

| UCP3 | ↓ | ↓ |

Note: ↑ denotes increase; ↓ denotes decrease; = denotes no change. The pattern is consistent with a return to the foetal gene programme. See text for details. (Adapted from Taegtmeyer.10)

Table 2.

Loading and unloading expose the plasticity of the cardiomyocyte

| Loading | Causes | Unloading | Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic overload | Obesity | Bariatric surgery | Reversible |

| Diabetes | Drugs (e.g. Metformin, DPP4 inhibitors) | Mixed results | |

| Haemodynamic overload | |||

| Physiological | Frequent exercise | Rest | Reversible |

| Pathological | Hypertension | LVAD | Mixed results |

| Aortic stenosis | AVR | Mixed results | |

| Unloading | Causes | Reloading | Consequences |

| Metabolic unloading | Starvation/nutrient deprivation cachexia | Feeding/nutrient delivery | Reversible |

| Haemodynamic unloading | Prolonged bed rest | Exercise/plasma volume restoration | Reversible |

| Space flight | Exercise/plasma volume restoration | Reversible | |

| Severed papillary muscle | Reattached muscle | Reversible | |

| Heterotopic transplantation | Balloon inflation | Reversible | |

Note: We distinguish between metabolic and haemodynamic loading, unloading, and reloading. DPP4, dipeptidyl peptidase; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; AVR, aortic valve replacement. See Text for details.

3. Metabolic stresses as modulators of cardiac structure and function

Besides adrenergic and angiotensin receptor activation, the main stressors of the heart are its metabolic and/or haemodynamic load. The beneficial effects of receptor blockade in heart failure management are well known.13 Modulation of the haemodynamic load is also a well-established concept, which will be discussed later. However, metabolic stresses, including increased nutrient supply, hyper-adrenergic states, or hormonal imbalances as modulators of cardiac structure and function are not always considered (with the notable exception of myocardial ischaemia, of course).

Obesity, insulin resistance, and diabetes mellitus are characterized by an extracellular milieu of excess fuel supply resulting in metabolic stress on the heart. The effects of obesity on the heart are well known and include impaired diastolic function,14 decreased cardiac efficiency,15 and left ventricular hypertrophy.16 The intramyocardial lipid accumulation in the failing human heart from obese and/or diabetic patients resembles features of the lipotoxic rat heart including oxidative stress, diacylglycerol, and ceramide accumulation.17 Altogether these characteristics comprise both markers (‘footprints') and mediators of glucolipotoxicity, a term first used by Marc Prentki and Barbara Corkey in the pancreatic β-cell.18 The complexities of glucolipotoxicity in the heart include metabolic and functional derangements, which have been reviewed in the context of obesity19,20 and diabetes.21,22

Metabolic disorders stem from several factors, including genetic predisposition on the one hand and the environment on the other hand. Diet is a critical determinant of adaptation and maladaptation of the heart. Along these lines, feeding rats two different obesogenic diets (60% or 45% of caloric intake from fat, 20% from protein and the balance from carbohydrate) resulted in two distinct forms of cardiac responses. High-fat (60% fat, 20% carbohydrate) diet induced futile metabolic cycles allowing the heart to adapt to metabolic overload, while ‘Western' (45% fat, 35% carbohydrate) diet resulted in heart failure.23 Maladaptation, revealed by the footprints of glucolipotoxicity in heart and skeletal muscle, is evident in all patients with clinically severe obesity24 and in all patients with either obesity or type 2 diabetes and advanced heart failure requiring cardiac transplantation.17

In short, there are multiple factors, both metabolic and neurohumoral, responsible for myocardial fuel overload. McEwen25 was probably the first to draw attention to the plasticity of the brain in relationship to stresses, which he collectively called ‘allostatic load'. The collective environmental risk for disease development in any organ has recently been given the term ‘exposome’.26 We now propose that metabolic loading, like haemodynamic loading, provides a stress to the heart which results in either adaptive or maladaptive, reversible or irreversible structural and functional changes. Reversibility of the process is borne out by the observation that prolonged caloric restriction in obese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus decreases myocardial triglyceride content and improves cardiac function27 and that muscle triglyceride accumulation as well as left ventricular diastolic dysfunction disappears as the metabolic profile normalizes after bariatric surgery.24

4. Haemodynamic stresses as modulators of cardiac structure and function

The development of physiological and pathological cardiac hypertrophy, in response to either volume or pressure overload, respectively, is well described. The molecular mechanisms responsible for these changes have been extensively reviewed.28–31 The dynamic nature of the heart muscle is evident by drastic increases and decreases in cardiac mass with physical conditioning and deconditioning.32–34 Furthermore, treatment of heart failure with implantation of a left ventricular assist device (LVAD)12 has suggested that even pathological hypertrophy may be potentially reversible with mechanical unloading.

The consequences of haemodynamic stresses on the heart are better defined than the metabolic stresses referred to above and have been the subject of many excellent papers.29,30,35 The Law of Laplace states that wall stress is directly proportional to chamber radius and pressure, and indirectly proportional to twice its wall thickness. Consequently the hypertrophy response (i) reduces wall stress, and (ii) should be reversible upon removal of the increasing haemodynamic stress—a frequent clinical observation after the surgical correction of significant cardiac lesions.36,37

5. The concept of cardiac plasticity

In the two sections above we introduced the concepts of metabolic and haemodynamic stress, and we have made reference to the consequences of stress removal. Over a wide range of environmental stimuli, trophic responses of the heart are reversible.38 Although the dividing line between reversible and irreversible structural and functional changes remains still elusive, some general principles have emerged.

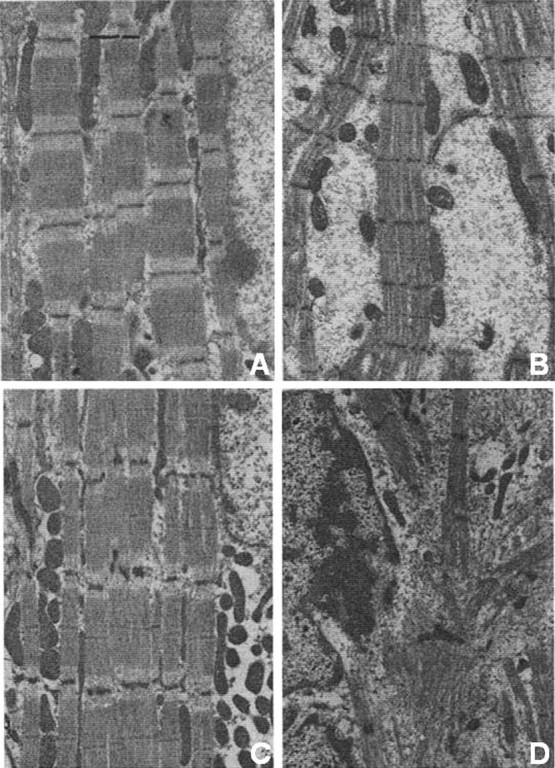

The induction of hypertrophy and its reversal as well as the reversible induction of atrophy39 have collectively been termed ‘cardiac plasticity'.35 These processes are both rapid and adaptive. The concept of plasticity is further supported by the simultaneous activation of protein synthesis and degradation in the unloaded rat heart.40 Striking examples for cardiac plasticity are the structural and biochemical changes in unloaded and re-loaded right ventricular papillary muscles of the intact feline myocardium, discussed in more detail later (Figure 2). In short, atrophic remodelling is reversible and reveals an important aspect of plasticity of the heart.

Figure 2.

Dynamic structural remodelling of cat papillary muscles in response to haemodynamic unloading and reloading. Electron micrographs of longitudinal sections under the following conditions: (A) Control; (B) 1 week of unloading; (C) 1 week of unloading, followed by 2 weeks of reloading; (D) Control, shortly after birth. The images show reversal of structural changes in heart. See text for further details. (With permission from Kent et al., JMCC 1985.39)

Taking the pressure off the heart results in the adaptation to a new physiological state, often referred to as ‘reverse remodelling'. By definition, reverse remodelling involves elements of cardiac atrophy, i.e. a situation where rates of protein degradation exceed rates of protein synthesis in the heart.41,42 The consequences of metabolic and haemodynamic unloading are discussed below.

6. Metabolic unloading

There are several scenarios of metabolic unloading of the heart. The first is starvation- or nutrient deprivation-induced cardiac atrophy. In the early phase of starvation, there is rapid induction of protein breakdown which provides amino acids to fuel gluconeogenesis in the liver.43 Detailed aspects of the clinical incidence and characterization of atrophy during nutrient deprivation have been described.44 Enhanced protein degradation [through both the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) and autophagy] is the main contributing factor during short-term starvation-induced cardiac atrophy in rabbits,45 which can be reversed by refeeding.46 The heart also atrophies in response to nutrient deprivation resulting from cachexia. Several new models of cachexia-induced cardiac atrophy have recently been described. Myostatin, a member of the transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) super family and a negative regulator of muscle bulk in skeletal muscle,47 induces muscle wasting and cachexia. In an elegant series of experiments, Heineke et al.48 demonstrated recently that heart muscle releases myostatin (not unlike TNFα), and induces muscle wasting in heart failure. Heart-specific over expression of myostatin reduced both heart weight and skeletal muscle weight. Myostatin-induced muscle wasting and cardiac atrophy can be blocked when mice are treated with a soluble receptor of myostatin.49 Another, clinically even more relevant, model is cancer-induced cachexia in mice. Cardiac atrophy due to nutritional unloading is associated with a return to the foetal gene programme, very much a sign of active cardiac remodelling in response to nutritional remodelling.50 Furthermore, cancer-induced cardiac atrophy seems to be regulated by autophagy, not the UPS.51

A third example is the reversal of metabolic overload from dysregulated substrate supply in obesity, insulin resistance, and diabetes, which results in features of glucolipotoxicity. The term ‘glucolipotoxicity’ was first used in the context of metabolic damage to the pancreatic β-cell,18 to denote the damage exerted by non-oxidative glucose and fatty acid metabolites in a variety of tissues including the heart. Virchow52 already described it as the ‘true metamorphosis of the cardiac cell’. Today lipotoxic heart disease is described in obese rats53,54 as much as in obese human patients with advanced heart failure.17 Metabolic unloading of the systemic circulation with the thiazolidinedione (TZD) troglitazone53 or with another, non-TZD compound55 results in complete reversal of both fuel overload and contractile dysfunction of the heart.

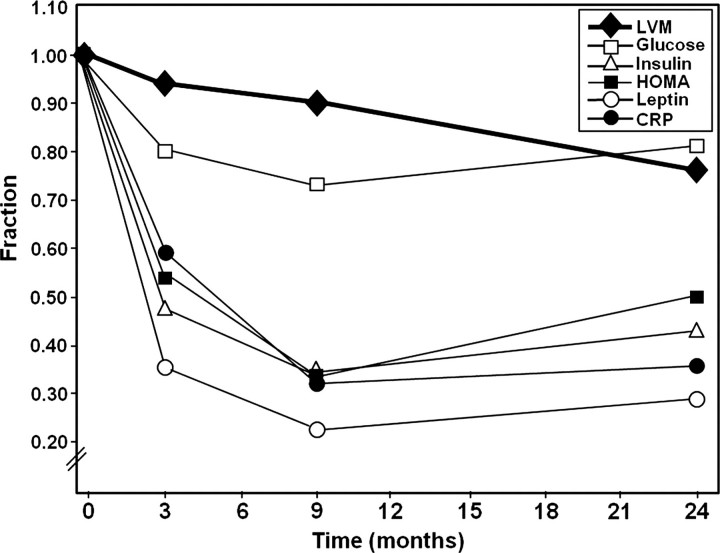

Perhaps the most impressive reversal of cardiac dysfunction and hypertrophy in response to metabolic stress occurs, however, in severely obese patients following bariatric surgery. Here the early normalization of hormone and substrate levels (and insulin resistance) is followed by a dramatic improvement in left ventricular diastolic function,24 as well as a progressive decrease in left ventricular mass.16 The left ventricle becomes smaller and stronger with the removal of the systemic metabolic pressure (Figure 3). To the contrary, increased fatty acid metabolism using a pharmacological activator of the nuclear receptor, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor, (PPARα) in the hypertrophied heart promotes fuel overload and results in contractile failure.56 We conclude that the removal of an excess nutrient supply to the heart, in contrast to cachexia, is beneficial for both size and function of the heart.

Figure 3.

Progressive regression of left ventricular mass after metabolic unloading by bariatric surgery. Drastic reduction in metabolic parameters (glucose, insulin, HOMA, leptin, CRP) occurs early after surgery and plateau after 9 months (metabolic unloading). Left ventricular mass continues to regress 24 months after surgery (HOMA, homeostasis model of assessment; LVM, left ventricular mass; CRP, C-reactive protein). (With permission from Algahim et al., Am J Med 2010.16)

7. Haemodynamic unloading

The functional and structural changes of the heart to haemodynamic unloading are complex. There is little doubt that in the failing human heart mechanical unloading improves, or even normalizes, Ca2+ cycling in the cardiomyocyte;57 remodels the extracellular matrix,58 reduces interstitial fibrosis, and decreases the size of heart muscle cells.12 In contrast to this pattern of structural and functional improvement with mechanical unloading of the failing human heart, no consistent pattern has been apparent at the transcriptional level.59 In the normal heart, we have drawn attention to the fact that the common feature of both pressure overload-induced hypertrophy and atrophy is a reactivation of the foetal gene programme (Table 1).2 Moreover, the metabolic consequences for the heart, including impaired insulin-responsiveness, are also the same for the hypertrophied and atrophied heart.60 In concurrence with this trend, El-Armouche et al.61 recently reported that microRNA signature patterns are also common in the unloaded and overloaded heart.

Many studies have reported the improvement of pathological hypertrophy with placement of a LVAD when used as a ‘bridge to transplantation’ in heart failure patients.12,62–64 Patients with LVAD support exhibit a reduced ventricular mass as a result of regression in myocyte hypertrophy.65 Mechanical unloading with LVADs may also improve the ejection fraction and reduce left ventricular end-diastolic dimensions,63,66 improve myocyte contractility, and increase β-adrenergic responsiveness.67 Although great strides have been made,12,58,68–70 more studies are still necessary in order to understand the mechanisms regulating ‘reverse remodelling' of the failing heart.

Similar to the failing heart, the normal heart can also be haemodynamically unloaded, as is the case of prolonged bed rest and space-flight, or ‘deconditioning' of the heart. Cardiac atrophy, resulting from extended periods of bed rest, is in part due to hypovolaemia71 and can be reversed with exercise and by inducing lower body negative pressure.72 Likewise, space-flight leads to decreased stroke volume and decreased systemic oxygen uptake due to decreased blood volume, collectively termed ‘microgravity-induced deconditioning’.73,74 Cardiac atrophy due to space-flight can be reversed with supine cycling exercises combined with plasma volume restoration.75

7.1. Unloading of the normal heart

A well-established experimental model of cardiac atrophy is the heterotopic transplantation of the mammalian heart. Initially introduced in the early 1930s in dogs,76 this method has more recently been adapted for rat heart transplantation studies.77–80 Additional modifications such as ‘pressure-loaded’81,82 and ‘volume-loaded’83,84 preparations of the unloaded heart have confirmed that alterations in cardiac structure and function are load-dependent. Heterotopic transplantation of the mouse heart has also been employed to investigate mechanisms of atrophic remodelling.85 We have utilized this model in transgenic animals to investigate gain- and loss-of-function studies as they relate to cardiac atrophy.86–88

Initial studies on atrophic remodelling of the normal heart focused on the structural and functional changes that occur in the absence of a load. Over a period of 28 days, cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area progressively decreases, with the earliest structural changes, including disarray of myofilaments, visible 1 day after unloading the feline papillary muscle.89 After 1 week, large areas of non-specific cytosol devoid of organelles are evident (Figure 2B).90 Surgically reloading the papillary muscle demonstrates the reversibility of atrophic remodelling: contractile filaments, mitochondria, and protein concentrations are restored, and the cytosol is replaced with organized myofibrils (Figure 2C).39 Additional studies in vitro using isolated adult feline myocytes verified that structural and biochemical changes observed in vivo are load-dependent.91 In the unloaded rat heart, an overall decrease in cardiac size and mass results from decreased cardiomyocyte size, not cardiomyocyte number,92 and cardiomyocytes within the left ventricular endomyocardium respond most drastically to unloading.93 Furthermore, decreased phospholipid concentrations in the sarcolemma occur in response to unloading, which may be due, at least in part, to decreased lipid incorporation.94 After long-term unloading there is increased ventricular stiffness,95 likely caused by increased extracellular matrix remodelling, which can be reversed with reloading.39 Despite the gross structural changes, normal functional capillary density is maintained in the unloaded heart.96,97

7.2. Ca2+ homeostasis in atrophic remodelling

Although atrophic remodelling significantly decreases myocyte area and volume, hearts maintain normal systolic function after 4 weeks of unloading.98 Cardiomyocytes from unloaded hearts have decreased sodium currents and increased calcium currents, while total calcium concentration in the myocyte remains unchanged.99 Cardiomyocytes have preserved fractional shortening and peak systolic [Ca2+]i at baseline, but have prolonged time to 50% relengthening and time to 50% decline in [Ca2+]i after unloading. Alterations in calcium handling may be, at least partially, due to increased phospholamban protein levels.100 Although isometric contraction and calcium-stimulated ATPase activity is not affected, decreased calcium uptake in the sarcoplasmic reticulum occurs with unloading, which may contribute to a decreased relaxation phase.101 Cardiomyocytes from hearts unloaded for 2 weeks have preserved fractional shortening and time to peak contraction and relaxation times, but papillary muscles develop less maximal force.100,102 When taking into account a decrease in myocyte size, however, there is no difference in maximal force per area in the unloaded heart.

7.3. Substrate metabolism and growth signalling

Early studies in the transplanted mammalian heart focused on structural and functional changes that occur in cardiomyocytes after unloading; however, the molecular mechanisms regulating these changes are still largely unclear. We demonstrated that in both atrophy and hypertrophy, the heart is less responsive to insulin and prefers glucose as substrate, consistent with the observed foetal pattern of energy consumption.60 Switch in substrate utilization in the unloaded heart is also reflected in the decreased expression of PPARα103 and the PPARα-regulated genes pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK4), and malonyl-CoA decarboxylase (MCD).104 Downregulation of PPARα in unloaded hearts is likely due to the activation of the IKKβ/p65/p50 pathway.86 We also investigated the role of growth factors, the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathway, and the Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway in the unloaded heart. Atrophic remodelling was associated with increased IGF-1 and FGF-2 mRNA expression and increased ERK1, p70S6K, and STAT3 phosphorylation.105 As is the case with the foetal gene programme, changes in growth factor expression are the same in both atrophy and hypertrophy, suggesting that directionality of change in cardiac size does not necessarily correlate with the corresponding changes in transcript levels. The activation of cardiac growth signalling in atrophic remodelling is not readily explained other than by the remodelling process itself. In short, active remodelling occurs with increased or decreased load indicating that myocardial protein turnover is a critical regulator of cardiac mass.

7.4. Pathways of protein turnover

The pathways regulating protein synthesis have been well characterized in the heart,29,30 while protein degradation in the heart, by comparison, has been less studied. The three major pathways regulating protein degradation in the heart have been previously reviewed106 and include the calcium-dependent calpain system, lysosomal proteolysis and autophagy, and the UPS. The UPS degrades proteins in a specific manner.7 Ubiquitin ligases confer the specificity of the system by tagging the target proteins to be degraded with ubiquitin, and the tagged proteins are then degraded by the proteasome. The role of the UPS, specifically the ubiquitin ligases Atrogin-1 and MuRF1, in regulating cardiac mass is well documented during cardiac hypertrophy107–109 and in skeletal muscle atrophy.110,111 In the unloaded heart, we observed an increase in polyubiquitinated proteins and increased levels of a ubiquitin conjugating enzyme, UbcH2, suggesting that the UPS is an important regulator of cardiac mass during atrophic remodelling.40 Unexpectedly, we found a decrease in the transcript levels of the ubiquitin ligases Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 after 7 days of unloading, although these data are consistent with the increase in IGF-1, as both ligases are negatively regulated by the insulin signalling pathway.105 Although surprising, our findings do not rule out the importance of Atrogin-1 and MuRF-1 during early atrophic remodelling of the heart.

To further define the role of protein degradation in the unloaded heart, we also investigated the calpain system and autophagy during atrophic remodelling. We found that the transcript levels and activities of both Calpain 1 and 2 were increased in the unloaded heart. However, in unloaded hearts overexpressing the endogenous calpain inhibitor calpastatin, atrophy was not inhibited, suggesting that more than one proteolysis pathway is involved in the atrophic remodelling process.88 In ongoing work, we also postulate that autophagy is an important mechanism regulating protein degradation in the unloaded heart. We found that markers of autophagy including LC3, Atg5, and Agt12 are increased at both the RNA and protein levels in the unloaded heart.112 In contrast, the failing human heart already expresses elevated levels of autophagy markers but when implanted with an LVAD, autophagy markers are downregulated.68,69 These data suggest that autophagy could be an adaptive mechanism in the failing heart; however, they do not rule out the possibility that autophagy in end-stage heart failure could be maladaptive. More studies, including gain- and loss-of-function studies will be necessary to clearly define the role of autophagy in atrophic remodelling of the heart.

Skeletal muscle atrophy due to disuse, or unloading, is caused by increased protein degradation and a decreased protein synthesis.113 We therefore reasoned that in the heart, protein synthesis would be decreased during atrophy. We unexpectedly found, however, that the mTOR pathway is activated with unloading. When the mTOR pathway is inhibited with rapamycin, there is a further decrease in cardiac mass in the unloaded heart.40 Simultaneous activation of protein synthesis (mTOR pathway) and protein degradation (the UPS, the calpain system, and autophagy) provides evidence that active remodelling occurs in the unloaded heart. To further understand the mechanisms involved in this process, we are currently investigating the hypothesis that metabolic signals regulate protein turnover during atrophic remodelling of the heart.

8. Outlook

A new paradigm is needed to assess the causes and consequences of atrophic remodelling of the heart. We have reviewed, in broad strokes, the consequences of metabolic and haemodynamic overload, the consequences of unloading the heart, and the many levels of complexity of atrophic remodelling. The latter include changes in gene expression, changes in protein abundance and activity, and changes in metabolites and metabolic fluxes. The powerful tools of discovery research and systems biology continue to add to the large pool of information. Great strides have been made in the field of cardiovascular proteomics giving rise to a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics involved in disease pathogenesis,114an example being the identification of novel posttranslational modifications of mitochondrial proteins.115 Advancements in the analysis and quantitation of protein biomarkers will continue to improve clinical diagnosis.116 Coupled with proteomics, metabolomics becomes a valuable resource to elucidate the link between cellular metabolism and cardiac function.117,118 In short, new analytical methods will help to find an answer to the question: How does the heart shrink and become stronger at the same time?

Funding

Work from the authors’ lab was supported in part by the US Public Health Service (R01 HL061483).

Acknowledgement

We thank Mrs Roxy A. Tate for expert editorial assistance.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Castle WB. Intellectual curiosity and the physician's responsibilities. Pharos. 1959;22:24–30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Depre C, Shipley GL, Chen W, Han Q, Doenst T, Moore M, et al. Unloaded heart in vivo replicates fetal gene expression of cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med. 1998;4:1269–1275. doi: 10.1038/3253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chien KR. Regenerative medicine and human models of human disease. Nature. 2008;453:302–305. doi: 10.1038/nature07037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsieh PC, Segers VF, Davis ME, MacGillivray C, Gannon J, Molkentin JD, et al. Evidence from a genetic fate-mapping study that stem cells refresh adult mammalian cardiomyocytes after injury. Nat Med. 2007;13:970–974. doi: 10.1038/nm1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herrmann J, Ciechanover A, Lerman LO, Lerman A. The ubiquitin-proteasome system in cardiovascular diseases-a hypothesis extended. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang X, Robbins J. Heart failure and protein quality control. Circ Res. 2006;99:1315–1328. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000252342.61447.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willis MS, Townley-Tilson WH, Kang EY, Homeister JW, Patterson C. Sent to destroy: the ubiquitin proteasome system regulates cell signaling and protein quality control in cardiovascular development and disease. Circ Res. 2010;106:463–478. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.208801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Depre C, Young ME, Ying J, Ahuja HS, Han Q, Garza N, et al. Streptozotocin-induced changes in cardiac gene expression in the absence of severe contractile dysfunction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:985–996. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taegtmeyer H, Golfman L, Sharma S, Razeghi P, van Arsdall M. Linking gene expression to function: metabolic flexibility in the normal and diseased heart. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1015:202–213. doi: 10.1196/annals.1302.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taegtmeyer H. Genetics of energetics: transcriptional responses in cardiac metabolism. Ann Biomed Eng. 2000;28:871–876. doi: 10.1114/1.1312187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Razeghi P, Young ME, Alcorn JL, Moravec CS, Frazier OH, Taegtmeyer H. Metabolic gene expression in fetal and failing human heart. Circulation. 2001;104:2923–2931. doi: 10.1161/hc4901.100526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Razeghi P, Myers TJ, Frazier OH, Taegtmeyer H. Reverse remodeling of the failing human heart with mechanical unloading. Emerging concepts and unanswered questions. Cardiology. 2002;98:167–174. doi: 10.1159/000067313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz AM. Heart Failure: Pathophysiology, Molelcular Biology and Clinical Management. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a Wolters Kluwer business; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leichman JG, Aguilar D, King TM, Vlada A, Reyes M, Taegtmeyer H. Association of plasma free fatty acids and left ventricular diastolic function in patients with clinically severe obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:336–341. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterson LR, Herrero P, Schechtman KB, Racette SB, Waggoner AD, Kisrieva-Ware Z, et al. Effect of obesity and insulin resistance on myocardial substrate metabolism and efficiency in young women. Circulation. 2004;109:2191–2196. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127959.28627.F8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Algahim MF, Lux TR, Leichman JG, Boyer AF, Miller CC, III, Laing ST, et al. Progressive regression of left ventricular hypertrophy two years after bariatric surgery: an unexpected dissociation with the body mass index. Am J Med. 2010;123:549–555. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma S, Adrogue JV, Golfman L, Uray I, Lemm J, Youker K, et al. Intramyocardial lipid accumulation in the failing human heart resembles the lipotoxic rat heart. FASEB J. 2004;18:1692–1700. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2263com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prentki M, Corkey BE. Are the beta-cell signaling molecules malonyl-Coa and cystolic long-chain acyl-Coa implicated in multiple tissue defects of obesity and niddm? Diabetes. 1996;45:273–283. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.3.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abel ED, Litwin SE, Sweeney G. Cardiac remodeling in obesity. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:389–419. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harmancey R, Wilson CR, Taegtmeyer H. Adaptation and maladaptation of the heart in obesity. Hypertension. 2008;52:181–187. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.110031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young ME, McNulty P, Taegtmeyer H. Adaptation and maladaptation of the heart in diabetes: part II: potential mechanisms. Circulation. 2002;105:1861–1870. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012467.61045.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taegtmeyer H, McNulty P, Young ME. Adaptation and maladaptation of the heart in diabetes: part I: general concepts. Circulation. 2002;105:1727–1733. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012466.50373.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson CR, Tran MK, Salazar KL, Young ME, Taegtmeyer H. Western diet, but not high fat diet, causes derangements of fatty acid metabolism and contractile dysfunction in the heart of Wistar rats. Biochem J. 2007;406:457–467. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leichman JG, Wilson EB, Scarborough T, Aguilar D, Miller CC, III, Yu S, et al. Dramatic reversal of derangements in muscle metabolism and diastolic left ventricular function after bariatric surgery. Am J Med. 2008;121:966–973. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McEwen BS. Stress, adaptation, and disease: allostasis and allostatic load. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;840:33–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rappaport SM, Smith MT. Epidemiology. Environment and disease risks. Science. 2010;330:460–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1192603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hammer S, Snel M, Lamb HJ, Jazet IM, van der Meer RW, Pijl H, et al. Prolonged caloric restriction in obese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus decreases myocardial triglyceride content and improves myocardial function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dorn GW., II The fuzzy logic of physiological cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertension. 2007;49:962–970. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.079426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frey N, Olson EN. Cardiac hypertrophy: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:45–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heineke J, Molkentin JD. Regulation of cardiac hypertrophy by intracellular signalling pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:589–600. doi: 10.1038/nrm1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rothermel BA, Hill JA. Autophagy in load-induced heart disease. Circ Res. 2008;103:1363–1369. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.186551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hickson RC, Galassi TM, Dougherty KA. Repeated development and regression of exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy in rats. J Appl Physiol. 1983;54:794–797. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.54.3.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ehsani AA, Hagberg JM, Hickson RC. Rapid changes in left ventricular dimensions and mass in response to physical conditioning and deconditioning. Am J Cardiol. 1978;42:52–56. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(78)90984-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pelliccia A, Maron BJ, De Luca R, Di Paolo FM, Spataro A, Culasso F. Remodeling of left ventricular hypertrophy in elite athletes after long-term deconditioning. Circulation. 2002;105:944–949. doi: 10.1161/hc0802.104534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hill J, Olson E. Cardiac plasticity. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1370–1380. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petrov G, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Lehmkuhl E, Krabatsch T, Dunkel A, Dandel M, et al. Regression of myocardial hypertrophy after aortic valve replacement: faster in women? Circulation. 2010;122:S23–S28. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.927764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suri RM, Zehr KJ, Sundt TM, III, Dearani JA, Daly RC, Oh J, et al. Left ventricular mass regression after porcine versus bovine aortic valve replacement: a randomized comparison. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:1232–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.04.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meerson FZ. The Failing Heart: Adaptation and Deadaptation. New York City: Raven Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kent RL, Uboh CE, Thompson EW, Gordon SS, Marino TA, Hoober J, et al. Biochemical and structural correlates in unloaded and reloaded cat myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1985;17:153–165. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(85)80018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Razeghi P, Sharma S, Ying J, Li YP, Stepkowski S, Reid MB, et al. Atrophic remodeling of the heart in vivo simultaneously activates pathways of protein synthesis and degradation. Circulation. 2003;108:2536–2541. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000096481.45105.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Razeghi P, Baskin KK, Sharma S, Young ME, Stepkowski S, Faadiel Essop M, et al. Atrophy, hypertrophy, and hypoxemia induce transcriptional regulators of the ubiquitin proteasome system in the rat heart. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;342:361–364. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Razeghi P, Taegtmeyer H. Cardiac remodeling: ups lost in transit. Circ Res. 2005;97:964–966. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000193563.53859.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruderman NB. Muscle amino acid metabolism and gluconeogenesis. Annu Rev Med. 1975;26:245–258. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.26.020175.001333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hellerstein HK, Santiago-Stevenson D. Atrophy of the heart; a correlative study of 85 proved cases. Circulation. 1950;1:93–126. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.1.1.93. illust. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Samarel AM, Parmacek MS, Magid NM, Decker RS, Lesch M. Protein synthesis and degradation during starvation-induced cardiac atrophy in rabbits. Circ Res. 1987;60:933–941. doi: 10.1161/01.res.60.6.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crie JS, Sanford CF, Wildenthal K. Influence of starvation and refeeding on cardiac protein degradation in rats. J Nutr. 1980;110:22–27. doi: 10.1093/jn/110.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McPherron AC, Lee SJ. Double muscling in cattle due to mutations in the myostatin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:12457–12461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heineke J, Auger-Messier M, Xu J, Sargent M, York A, Welle S, et al. Genetic deletion of myostatin from the heart prevents skeletal muscle atrophy in heart failure. Circulation. 2010;121:419–425. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.882068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou X, Wang JL, Lu J, Song Y, Kwak KS, Jiao Q, et al. Reversal of cancer cachexia and muscle wasting by actriib antagonism leads to prolonged survival. Cell. 2010;142:531–543. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tian M, Nishijima Y, Asp ML, Stout MB, Reiser PJ, Belury MA. Cadiac alertations in cancer-induced cachexia in mice. Int J Oncol. 2010;37:347–353. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cosper PF, Leinwand LA. Cancer causes cardiac atrophy and autophagy in a sexually dimorphic manner. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1710–1720. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Virchow R. Die zellularpathologie und ihre begründung auf physiologische und pathologische gewebelehre. Berlin: Hirschwald, A; 1858. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou YT, Grayburn P, Karim A, Shimabukuro M, Higa M, Baetens D, et al. Lipotoxic heart disease in obese rats: implications for human obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1784–1789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Young ME, Guthrie PH, Razeghi P, Leighton B, Abbasi S, Patil S, et al. Impaired long-chain fatty acid oxidation and contractile dysfunction in the obese Zucker rat heart. Diabetes. 2002;51:2587–2595. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.8.2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Golfman LS, Wilson CR, Sharma S, Burgmaier M, Young ME, Guthrie PH, et al. Activation of PPAR-gamma enhances myocardial glucose oxidation and improves contractile function in isolated working hearts of zdf rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289:E328–E336. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00055.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Young ME, Laws FA, Goodwin GW, Taegtmeyer H. Reactivation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha is associated with contractile dysfunction in hypertrophied rat heart. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44390–44395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103826200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chaudhary KW, Rossman EI, Piacentino V, III, Kenessey A, Weber C, Gaughan JP, et al. Altered myocardial Ca2+ cycling after left ventricular assist device support in the failing human heart. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:837–845. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bruckner BA, Razeghi P, Stetson S, Thompson L, Lafuente J, Entman M, et al. Degree of cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy at time of implantation predicts myocardial improvement during left ventricular assist device support. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23:36–42. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(03)00103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Margulies KB, Matiwala S, Cornejo C, Olsen H, Craven WA, Bednarik D. Mixed messages: transcription patterns in failing and recovering human myocardium. Circ Res. 2005;96:592–599. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000159390.03503.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Doenst T, Goodwin GW, Cedars AM, Wang M, Stepkowski S, Taegtmeyer H. Load-induced changes in vivo alter substrate fluxes and insulin responsiveness of rat heart in vitro. Metabolism. 2001;50:1083–1090. doi: 10.1053/meta.2001.25605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.El-Armouche A, Schwoerer AP, Neuber C, Emmons J, Biermann D, Christalla T, et al. Common microrna signatures in cardiac hypertrophic and atrophic remodeling induced by changes in hemodynamic load. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Margulies KB. Reversal mechanisms of left ventricular remodeling: lessons from left ventricular assist device experiments. J Card Fail. 2002;8:S500–S505. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2002.129264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maybaum S, Kamalakannan G, Murthy S. Cardiac recovery during mechanical assist device support. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;20:234–246. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Burkhoff D, Klotz S, Mancini DM. LVAD-induced reverse remodeling: basic and clinical implications for myocardial recovery. J Card Fail. 2006;12:227–239. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zafeiridis A, Jeevanandam V, Houser SR, Margulies KB. Regression of cellular hypertrophy after left ventricular assist device support. Circulation. 1998;98:656–662. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.7.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maybaum S, Mancini D, Xydas S, Starling RC, Aaronson K, Pagani FD, et al. Cardiac improvement during mechanical circulatory support: a prospective multicenter study of the LVAD working group. Circulation. 2007;115:2497–2505. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.633180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dipla K, Mattiello JA, Jeevanandam V, Houser SR, Margulies KB. Myocyte recovery after mechanical circulatory support in humans with end-stage heart failure. Circulation. 1998;97:2316–2322. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.23.2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kassiotis C, Ballal K, Wellnitz K, Vela D, Gong M, Salazar R, et al. Markers of autophagy are downregulated in failing human heart after mechanical unloading. Circulation. 2009;120:S191–S197. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.842252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wellnitz K, Taegtmeyer H. Mechanical unloading of the failing heart exposes the dynamic nature of autophagy. Autophagy. 2010;6:155–156. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.1.10538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Flesch M, Margulies KB, Mochmann HC, Engel D, Sivasubramanian N, Mann DL. Differential regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases in the failing human heart in response to mechanical unloading. Circulation. 2001;104:2273–2276. doi: 10.1161/hc4401.099449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Iwasaki KI, Zhang R, Zuckerman JH, Pawelczyk JA, Levine BD. Effect of head-down-tilt bed rest and hypovolemia on dynamic regulation of heart rate and blood pressure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R2189–R2199. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.6.R2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guell A, Braak L, Pavy Le Traon A, Gharib C. Cardiovascular deconditioning during weightlessness simulation and the use of lower body negative pressure as a countermeasure to orthostatic intolerance. Acta Astronaut. 1990;21:667–672. doi: 10.1016/0094-5765(90)90078-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Buckey JC, Jr, Lane LD, Levine BD, Watenpaugh DE, Wright SJ, Moore WE, et al. Orthostatic intolerance after spaceflight. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:7–18. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Levine BD, Lane LD, Watenpaugh DE, Gaffney FA, Buckey JC, Blomqvist CG. Maximal exercise performance after adaptation to microgravity. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:686–694. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.2.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Perhonen MA, Franco F, Lane LD, Buckey JC, Blomqvist CG, Zerwekh JE, et al. Cardiac atrophy after bed rest and spaceflight. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:645–653. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.2.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mann FC, Priestley JT, Markowitz J, Yater WM. Transplantation of the intact mammalian heart. Arch Surg. 1933;26:219–224. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abbott CP, Lindsey ES, Creech O, Jr, Dewitt CW. A technique for heart transplantation in the rat. Arch Surg. 1964;89:645–652. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1964.01320040061009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Abbott CP, Dewitt CW, Creech O., Jr The transplanted rat heart: histologic and electrocardiographic changes. Transplantation. 1965;3:432–445. doi: 10.1097/00007890-196505000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ono K, Lindsey ES. Improved technique of heart transplantation in rats. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1969;57:225–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang D, Opelz G, Terness P. A simplified technique for heart transplantation in rats: abdominal vessel branch-sparing and modified venotomy. Microsurgery. 2006;26:470–472. doi: 10.1002/micr.20272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Galinanes M, Zhai X, Hearse DJ. The effect of load on atrophy, myosin isoform shifts and contractile function: studies in a novel rat heart transplant preparation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1995;27:407–417. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(08)80037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tevaearai HT, Walton GB, Eckhart AD, Keys JR, Koch WJ. Heterotopic transplantation as a model to study functional recovery of unloaded failing hearts. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;124:1149–1156. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.127315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Asfour B, Hare JM, Kohl T, Baba HA, Kass DA, Chen K, et al. A simple new model of physiologically working heterotopic rat heart transplantation provides hemodynamic performance equivalent to that of an orthotopic heart. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1999;18:927–936. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(99)00062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Klein I, Hong C, Schreiber SS. Isovolumic loading prevents atrophy of the heterotopically transplanted rat heart. Circ Res. 1991;69:1421–1425. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.5.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Corry RJ, Winn HJ, Russell PS. Heart transplantation in congenic strains of mice. Transplant Proc. 1973;5:733–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Razeghi P, Wang ME, Youker KA, Golfman L, Stepkowski S, Taegtmeyer H. Lack of nf-kappab1 (p105/p50) attenuates unloading-induced downregulation of pparalpha and pparalpha-regulated gene expression in rodent heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;74:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Baskin KK, Chen W, Salazar RL, Taegtmeyer HT. The ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1, but not murf-1, is required for atrophic remodeling of the heart. Circulation. 2009;120:S761. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 88.Razeghi P, Volpini KC, Wang ME, Youker KA, Stepkowski S, Taegtmeyer H. Mechanical unloading of the heart activates the calpain system. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:449–452. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tomanek RJ, Cooper GT. Morphological changes in the mechanically unloaded myocardial cell. Anat Rec. 1981;200:271–280. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Thompson EW, Marino TA, Uboh CE, Kent RL, Cooper GT. Atrophy reversal and cardiocyte redifferentiation in reloaded cat myocardium. Circ Res. 1984;54:367–377. doi: 10.1161/01.res.54.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cooper GT, Mercer WE, Hoober JK, Gordon PR, Kent RL, Lauva IK, et al. Load regulation of the properties of adult feline cardiocytes. The role of substrate adhesion. Circ Res. 1986;58:692–705. doi: 10.1161/01.res.58.5.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schena S, Kurimoto Y, Fukada J, Tack I, Ruiz P, Pang M, et al. Effects of ventricular unloading on apoptosis and atrophy of cardiac myocytes. J Surg Res. 2004;120:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Campbell SE, Korecky B, Rakusan K. Remodeling of myocyte dimensions in hypertrophic and atrophic rat hearts. Circ Res. 1991;68:984–996. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.4.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Vasdev SC, Korecky B, Rastogi RB, Singhal RL, Kako KJ. Myocardial lipid metabolism in cardiac hyper- and hypo-function. Studies on triiodothyronine-treated and transplanted rat hearts. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1977;55:1311–1319. doi: 10.1139/y77-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brinks H, Tevaearai H, Muhlfeld C, Bertschi D, Gahl B, Carrel T, et al. Contractile function is preserved in unloaded hearts despite atrophic remodeling. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:742–746. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Korecky B, Hai CM, Rakusan K. Functional capillary density in normal and transplanted rat hearts. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1982;60:23–32. doi: 10.1139/y82-003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rakusan K, Heron M, Kolar F, Korecky B. Transplantation-induced atrophy of normal and hypertrophic rat hearts: effect on cardiac myocytes and capillaries. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:1045–1054. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kolar F, MacNaughton C, Papousek F, Korecky B. Systolic mechanical performance of heterotopically transplanted hearts in rats treated with cyclosporin. Cardiovasc Res. 1993;27:1244–1247. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.7.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ritter M, Su Z, Xu S, Shelby J, Barry W. Cardiac unloading alters contractility and calcium homeostasis in ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:577–584. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ito K, Nakayama M, Hasan F, Yan X, Schneider MD, Lorell BH. Contractile reserve and calcium regulation are depressed in myocytes from chronically unloaded hearts. Circulation. 2003;107:1176–1182. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000051463.72137.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Korecky B, Ganguly P, Elimban V, Dhalla N. Muscle mechanics and Ca++ transport in atrophic heart transplants in rat. Am J Physiol. 1986;251:H941–H948. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.251.5.H941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Welsh DC, Dipla K, McNulty PH, Mu A, Ojama KM, Klein I, et al. Preserved contractile function despite atrophic remodeling in unloaded rat hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H1131–H1136. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.3.H1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Young ME, Patil S, Ying J, Depre C, Ahuja HS, Shipley GL, et al. Uncoupling protein 3 transcription is regulated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (alpha) in the adult rodent heart. FASEB J. 2001;15:833–845. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0351com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Taegtmeyer H, Razeghi P, Young ME. Mitochondrial proteins in hypertrophy and atrophy: a transcript analysis in rat heart. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2002;29:346–350. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2002.03656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sharma S, Ying J, Razeghi P, Stepkowski S, Taegtmeyer H. Atrophic remodeling of the transplanted rat heart. Cardiology. 2006;105:128–136. doi: 10.1159/000090550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Razeghi P, Taegtmeyer H. Hypertrophy and atrophy of the heart: the other side of remodeling. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1080:110–119. doi: 10.1196/annals.1380.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Li HH, Kedar V, Zhang C, McDonough H, Arya R, Wang DZ, et al. Atrogin-1/muscle atrophy f-box inhibits calcineurin-dependent cardiac hypertrophy by participating in an scf ubiquitin ligase complex. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1058–1071. doi: 10.1172/JCI22220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Arya R, Kedar V, Hwang JR, McDonough H, Li HH, Taylor J, et al. Muscle ring finger protein-1 inhibits pkc{epsilon} activation and prevents cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:1147–1159. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200402033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Willis MS, Ike C, Li L, Wang DZ, Glass DJ, Patterson C. Muscle ring finger 1, but not muscle ring finger 2, regulates cardiac hypertrophy in vivo. Circ Res. 2007;100:456–459. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000259559.48597.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bodine SC, Latres E, Baumhueter S, Lai VK, Nunez L, Clarke BA, et al. Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science. 2001;294:1704–1708. doi: 10.1126/science.1065874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gomes MD, Lecker SH, Jagoe RT, Navon A, Goldberg AL. Atrogin-1, a muscle-specific f-box protein highly expressed during muscle atrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14440–14445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251541198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rajabi MSR, Razeghi P, Stepkowski S, Taegtmeyer H. Autophagy regulates remodeling in unloaded heart. J Card Fail. 2007;13:S99. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 113.Jackman RW, Kandarian SC. The molecular basis of skeletal muscle atrophy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C834–C843. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00579.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ping P, Chan DW, Srinivas P. Advancing cardiovascular biology and medicine via proteomics: opportunities and present challenges of cardiovascular proteomics. Circulation. 2010;121:2326–2328. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.949230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Balaban RS. The mitochondrial proteome: a dynamic functional program in tissues and disease states. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2010;51:352–359. doi: 10.1002/em.20574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Fu Q, Schoenhoff FS, Savage WJ, Zhang P, Van Eyk JE. Multiplex assays for biomarker research and clinical application: translational science coming of age. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2010;4:271–284. doi: 10.1002/prca.200900217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Mayr M, Madhu B, Xu Q. Proteomics and metabolomics combined in cardiovascular research. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2007;17:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mayr M. Metabolomics: ready for the prime time? Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2008;1:58–65. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.808329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]