Abstract

Like other apicomplexan parasites, Toxoplasma gondii actively invades host cells using a combination of secretory proteins and an acto-myosin motor system. Micronemes are the first set of proteins secreted during invasion that play an essential role in host cell entry. Many microneme proteins (MICs) function in protein complexes, and each complex contains at least one protein that displays a cleavable propeptide. Although MIC propeptides have been implicated in forward targeting to micronemes, the specific amino acids involved have not been identified. It was also not known if the propeptide has a general function in MICs trafficking in T. gondii and other apicomplexans. Here we show that propeptide domains are extensively interchangeable between T. gondii MICs and also with that of Eimeria tenella MIC5 (EtMIC5), suggesting a common mechanism of function. We also performed N-terminal deletion and mutational analysis of M2AP and MIC5 propeptides to show that a valine at position +3 (relative to signal peptidase cleavage) of proM2AP and a leucine at position +1 of proMIC5 are crucial for targeting to micronemes. Valine and leucine are closely related amino acids with similar side chains, implying a similar mode of function, a notion that was confirmed by correct trafficking of TgM2AP-V/L and TgMIC5-L/V substitution mutants. Propeptides of AMA1, MIC3, and EtMIC5 have valine or leucine at or near the N-termini and mutagenesis of these conserved residues validated their role in microneme trafficking. Collectively, our findings suggest that discrete, aliphatic residues at the extreme N-termini of proMICs facilitate trafficking to the micronemes.

Keywords: Apicomplexa, Toxoplasma gondii, Propeptide, Microneme, Trafficking

Introduction

Secretory proteins are released from eukaryotic cells either in a constitutive or regulated manner. Proteins destined for constitutive secretion generally do not carry codes for trafficking to specific destinations and are secreted soon after synthesis. In contrast regulated secretion often involves precise trafficking based on specific forward targeting elements contained within the proteins, storage in specific compartments and secretion in response to internal or external stimuli. Although regulated secretion has been the subject of intense research in recent years, the sorting signals that play a role in protein targeting to their destination organelle remain poorly defined in many biological systems (1).

T. gondii is an obligatory intracellular parasite that causes toxoplasmosis in humans and is classified in the phylum Apicomplexa. The phylum also includes pathogens of medical and veterinary importance such as the malaria parasites Plasmodium, the causative agent of malaria, and Eimeria, that causes coccidiosis in poultry. T. gondii infection is often asymptomatic in healthy individuals, but it can cause fatal toxoplasmic encephalitis in immuno-compromised patients such as those infected with HIV or patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy during organ transplantation procedures (2).

T. gondii entry into host cells is an essential step in its obligatory intracellular lifestyle and is thus considered potentially vulnerable to intervention. T. gondii host cell invasion is an active process that involves its own cytoskeleton machinery and regulated secretion of proteins from distinct secretory organelles including micronemes and rhoptries (3,4). Micronemes are cigar shaped organelles located at the apical end of the parasite. The contents of micronemes are discharged in response to a rise in intracellular calcium during gliding motility and initial contact of the parasite’s apical end with the host cell surface (5–8). Microneme proteins are not only crucial for binding to the host cell prior to entry but are also essential for parasite gliding motility, the basis for active invasion (9).

Microneme proteins generally function in complexes consisting of one transmembrane protein and one or more non-anchored proteins in which at least one protein contains a cleavable propeptide (10,11). MIC2-M2AP (9) and MIC3-MIC8 (12) are two of the key microneme complexes necessary for invasion. MIC2 is a thrombospondin-related anonymous protein (TRAP) family transmembrane protein that interacts with both host cell receptors and the cytoskeletal machinery of the parasite (13). M2AP is a soluble protein and contains a 24-amino acid N-terminal propeptide that is cleaved within the parasite endosomal system, which was recently shown to act as a conduit to the micronemes (14). MIC2 forms a heterohexameric complex with M2AP in the ER and remains associated during essential steps of attachment and invasion. Several studies have clearly established that the MIC2-M2AP complex is a central and rate-limiting component of the motility and invasion machinery of T. gondii (9,13,15,16). Accordingly, parasites in which these genes are knocked out or mutated are significantly compromised with regard to invasion and virulence in the mouse model (9,16). MIC8 is a transmembrane microneme protein that forms a complex with MIC3. Targeted disruption of MIC8 impairs moving junction formation thus significantly compromising parasite invasion (12).

Efficient functioning of microneme protein complexes requires correct trafficking of these proteins from their initial site of synthesis in the ER to the staging site for secretion, the micronemes. Although previous studies have shown that the cytoplasmic domains of MIC2 and MIC6 contain a microneme targeting motif (EIEYE) (17,18), recent studies have shown that these elements are not sufficient for directing the complex to the micronemes (15). In M2AP knockout (M2APKO) parasites, MIC2 is retained in the Golgi thus implying that soluble M2AP protein plays a role in trafficking (15). Further studies on M2AP showed that deletion of M2AP-propeptide (M2APΔpro) results in impaired trafficking of the MIC2-M2AP complex, indicating that the propeptide is necessary for trafficking to micronemes (19). Interestingly, M2APΔpro parasites also display a delayed time-to-death phenotype that is similar to M2APKO parasites thus emphasizing the relation between propeptide based trafficking of this complex and T. gondii virulence (19). A general role for microneme propeptides is also supported by studies on MIC5 and MIC3 as the deletion of their propeptides results in retention or mistargeting within the trafficking pathway (20,21). Additionally, a recent study looking at transmembrane microneme proteins such as MIC8, MIC8.2, MIC16 and AMA1 established that cytoplasmic domains do not contain microneme targeting information suggesting that either the ectodomain or soluble proteins within the complex contains microneme targeting information (22).

Although it is now well established that microneme propeptides are involved in trafficking, their precise role in facilitating entry into the micronemal pathway remains to be elucidated. For example, it is not known whether the forward targeting function of microneme propeptide domains is limited to T. gondii or shared by other apicomplexans. It is also unclear if the propeptide domains are competent only on their cognate proteins or whether they are widely interchangeable. Finally, since no conserved motifs have been identified in proMICs it remains unclear if targeting information is sequence specific. Hence the current study was undertaken to address these questions. We show that propeptide domains appear to be extensively interchangeable among different microneme proteins within T. gondii and also with the related apicomplexan parasite Eimeria tenella, suggesting a common mechanism of function. We also show by deletion and mutational analysis of microneme propeptides that aliphatic residues near the N-terminus act as important determinants of microneme trafficking.

Results

Microneme propeptide domains are extensively interchangeable

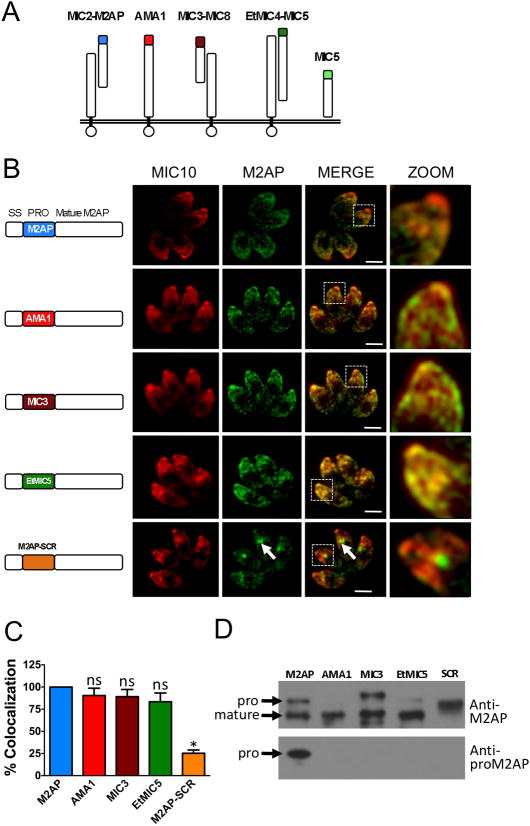

Previous work had demonstrated that microneme protein propeptides are required for trafficking and in at least one case they are functionally interchangeable (20). We sought to expand this analysis to other microneme propeptides in T. gondii and also in the related apicomplexan parasite Eimeria tenella (Fig. 1A). Having parasites deficient in either M2AP or MIC5 provided an ideal opportunity to study microneme trafficking in a background free of interference from expression of endogenous protein. To determine if microneme propeptides are widely interchangeable among different microneme proteins within T. gondii and also with Eimeria tenella, propeptide swapping experiments were performed. We designed plasmid constructs in which the M2AP propeptide is replaced with propeptides from AMA1, MIC3 or EtMIC5 and co-transfected them along with a selectable marker (pTUB/DHFR) into M2APKO parasites. The transfected parasites were cultured in the presence of pyrimethamine to obtain parasite cell lines stably expressing AMA1proM2AP, MIC3proM2AP, or EtMIC5proM2AP. The location of mature M2AP in intracellular parasites was analyzed by immunostaining with a polyclonal antibody against M2AP. Detection of MIC10 was used as a control for apical staining. Results showed that most of the mature M2AP protein co-localized with MIC10 indicating that AMA1, MIC3 or EtMIC5 propeptides can correctly deliver M2AP to the micronemes (Fig. 1B and C). These results suggest that the forward targeting function of microneme propeptides is conserved not only among different microneme proteins within T. gondii but also within the coccidia. The finding that microneme propeptide domains are able to substitute for one another in turn suggests that they likely function via a similar mechanism. To determine if propeptide-dependent trafficking is sequence specific, we generated parasites stably expressing a sequence-scrambled propeptide of M2AP (M2AP-SCR) fused to mature M2AP and examined by IFA. In this case, localization of M2AP with the scrambled propeptide was clearly distinct from MIC10, thus indicating that the order of amino acids in the propeptide is important for trafficking. The residual ~20% colocalization of M2AP-SCR with MIC10 is due to a combination of small amounts of M2AP-SCR that reach the micronemes and the presence of some MIC10 in the intermediate compartment where M2AP-SCR is retained. To examine the nature of propeptide processing, we performed immunoblot analysis of parasite lysates using anti-proM2AP and anti-M2AP antibodies. The results showed that all chimeric M2AP proproteins were of expected size and were processed correctly except M2AP-SCR (Fig. 1D). The lack of M2AP-SCR processing is likely due to disruption of the residues involved in protease recognition, since these residues lie mainly within the propeptide (19).

Figure 1.

The M2AP propeptide is interchangeable with other propeptides from T. gondii and E. tenella. A. Schematic representation of microneme complexes: MIC2-M2AP; AMA1; MIC3-MIC8, MIC5 of T. gondii and EtMIC4-MIC5 of E. tenella. B. Location of mature M2AP in intracellular parasites was examined by IFA using anti-M2AP and anti-MIC10 antibodies. MIC10 was used as the control for microneme staining. Arrows denote the site where the mature M2AP is retained in the secretory pathway. Displayed to the left of each image series is a schematic representation of constructs containing wild-type mature M2AP and replacement propeptides from AMA1, MIC3, EtMIC5 or sequence-scrambled M2AP propeptide (SCR) Scale bar: 2 μM. C. For this experiment and all subsequent experiments, the extent of colocalization of M2AP (or MIC5) and MIC10 was quantified by determining Pearson’s coefficient value using Axiovision software. Colocalization values obtained for parasites transfected with M2AP-WT (or MIC5-WT) were set at 100%. Results are from two experiments each measuring the colocalization within at least four vacuoles each with four parasites. Bars represent SEM. ns, not statistically different from WT i.e., P>0.05, one sample t-test. *, P<0.05. D. Parasites stably transfected with construct for expression of WT M2AP or replacement propeptide were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-M2AP and anti-proM2AP antibodies.

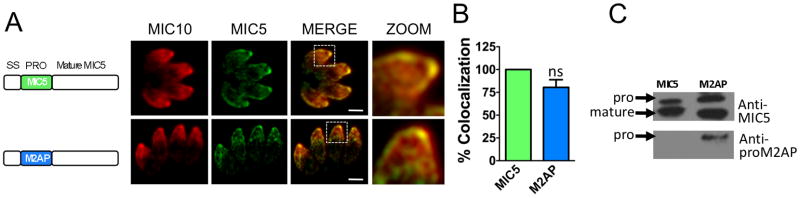

We also made a plasmid construct in which the M2AP propeptide is linked to mature MIC5 and co-transfected with pTUB/DHFR into MIC5KO parasites. The hybrid protein, M2APproMIC5, showed apical localization similar to MIC10, indicating that the M2AP propeptide can target mature MIC5 to micronemes (Fig. 2A and B). Immunoblot analysis using anti-proM2AP and anti-MIC5 antibodies confirmed the chimeric nature of M2APproMIC5 protein and also its correct processing (Fig. 2C). These results further confirm that propeptide domains are indeed extensively interchangeable in T. gondii.

Figure 2.

The MIC5 propeptide is interchangeable with that of M2AP. A. Location of mature MIC5 in intracellular parasites expressing WT MIC5 (upper panels) or M2APproMIC5 (lower panels) was examined by IFA using anti-MIC5 and anti-MIC10 antibodies. Scale bar: 2 μM. B. Quantification of MIC5 and MIC10 colocalization. Bars represent SEM. ns, not statistically different from WT i.e., P>0.05, one sample t-test. *, P<0.05. C. Parasites stably expressing WT-MIC5 and M2AP-MIC5 were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MIC5 and anti-proM2AP antibodies.

The third residue of the M2AP propeptide (valine) is important for microneme trafficking

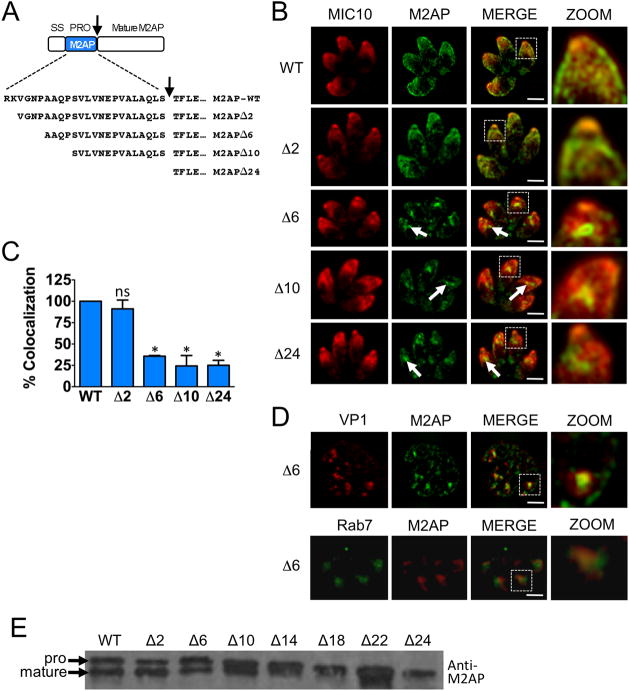

In an initial attempt to identify conserved residues in propeptides necessary for microneme targeting we performed comparative sequence analysis of microneme propeptides in T. gondii (see also Fig. 8A). Although all the microneme propeptide sequences have a net basic or neutral charge that contrasts with the acidic nature of the mature protein, no conserved motifs were observed. Hence, we moved forward with N-terminal deletion analysis of the M2AP propeptide to empirically identify residues necessary for trafficking. We designed plasmid constructs that contain serial deletions of the 24 amino acid M2AP propeptide. Initially seven constructs were made with deletions of 2 (Δ2), 6 (Δ6), 10 (Δ10), 14 (Δ14), 18 (Δ18), 22 (Δ22), and 24 (Δ24, M2APΔpro) amino acids of the M2AP propeptide (Fig. 3A). The plasmid constructs were transfected into M2APKO parasites and parasite cell lines stably expressing M2AP propeptide deletion mutants were obtained and examined by IFA. The results showed that while M2AP is correctly targeted to micronemes in parasites expressing full length M2AP (M2AP-WT) and M2APΔ2, it is largely retained in central apical location in all the subsequent deletion mutants (Fig. 3B and C, Fig. S1). Additional staining experiments showed that the M2AP trafficking mutants reside within the endosomal system where they displayed an overlapping distribution with the late endosomal markers Rab7 and VP1 (Fig. 3D). This mislocalization is similar to M2APΔpro mutants described previously (19,28). Immunoblot analysis with anti-M2AP antibody revealed that despite the mis-trafficking of M2APΔ6 and subsequent deletion constructs, propeptide processing of the mutants still occurs to a certain extent (Fig 3E). This is consistent with previous observations that M2AP processing occurs within the endosomal system and that M2AP trafficking and processing are mostly independent events (19,21). This first series of deletion analysis results indicated that a forward targeting element is located between the second and seventh residues of the M2AP propeptide i.e., within the sequence “VGNP”.

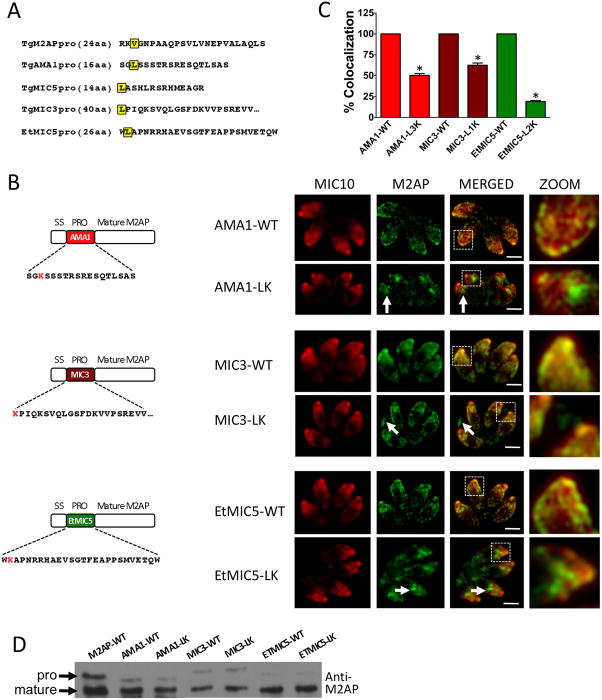

Figure 8.

Leucine near the N-terminus of microneme propeptides are important for correct trafficking. A. Propeptide sequences of M2AP, AMA1, MIC5, MIC3 and EtMIC5. B. Schematic representation of AMA1proM2AP, MIC3proM2AP and EtMIC5proM2AP in which the N- terminal leucine residues are replaced with lysine and location of mature M2AP in intracellular parasites examined by IFA using anti-M2AP and anti-MIC10 antibodies. MIC10 was used as the control for microneme staining. Arrows denote the site where the mature M2AP is retained or found in the PV in defective trafficking parasites. Scale bar: 2 μM. C. Quantification of M2AP and MIC10 colocalization. Bars represent SEM. ns, not statistically different from WT i.e., P>0.05, one sample t-test. *, P<0.05. D. Parasites stably transfected with wild-type replacement or mutant constructs were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-M2AP.

Figure 3.

Initial N-terminal serial deletion analyses of M2AP propeptide suggests that the “VGNP” region contains important residues required for trafficking. A. Schematic representation and sequences of full-length and N-terminal serial deletion constructs of M2AP propeptide. An arrow denotes the proteolytic cleavage site. B. Location of mature M2AP in intracellular parasites was examined by IFA using anti-M2AP and anti-MIC10 antibodies. Arrows denote the site where the mature M2AP is retained in the secretory pathway in parasites that showed defective trafficking. Scale bar: 2 μM. C. Quantification of M2AP and MIC10 colocalization. Bars represent SEM. ns, not statistically different from WT i.e., P>0.05, one sample t-test. *, P<0.05. D. Upper panel shows double immunolocalization of M2APΔ6 parasites with anti-M2AP and anti-VP1 antibodies. Lower panel shows M2APΔ6 parasites transiently transfected with HA tagged Rab7 and stained with anti-M2AP and anti-HA antibodies. E. Parasites stably transfected with full-length propeptide (WT) and deletion mutants were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-M2AP.

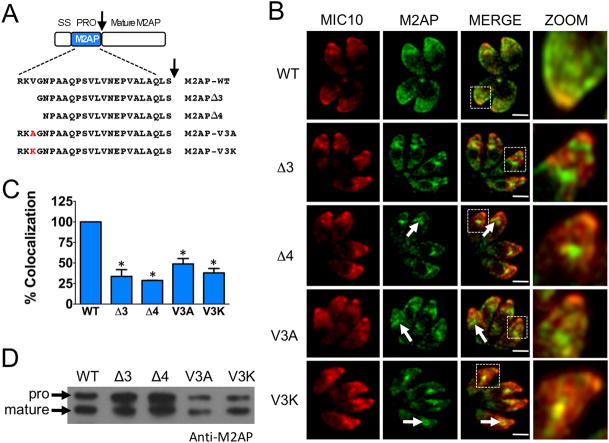

For finer dissection, we made deletion constructs that contained deletions of 3 (Δ3) and 4 (Δ4) amino acids of the M2AP propeptide (Fig. 4A) and transfected into M2APKO parasites. Both deletion constructs showed aberrant trafficking, thus indicating that the third residue of the M2AP propeptide (valine) is important for correct targeting (Fig. 4B and C). To validate this finding, we made parasite cell lines in which the third residue valine was replaced with either alanine or lysine. Analysis by IFA showed that M2AP was mis-trafficked in both the replacement mutants and the trafficking defect was more severe when valine was replaced with lysine (Fig. 4B and C), thus confirming that valine is indeed important for microneme targeting. Immunoblot analysis indicated that propeptide processing was still observed to a large extent in trafficking defective parasites (Fig. 4D), consistent with the earlier findings.

Figure 4.

Fine mapping of the “VGNP” region of M2AP propeptide shows that the third residue, valine, is important for trafficking. A. Schematic representation and sequences of full-length, deletion and replacement mutants of M2AP propeptide. An arrow denotes the proteolytic cleavage site. B. Location of mature M2AP in intracellular parasites was examined by IFA using anti-M2AP and anti-MIC10 antibodies. Arrows denote the site where the mature M2AP is retained in the secretory pathway in mutants that showed defective trafficking. Scale bar: 2 μM. C. Quantification of M2AP and MIC10 colocalization. Bars represent SEM. ns, not statistically different from WT i.e., P>0.05, one sample t-test. *, P<0.05. D. Parasites stably transfected with full-length propeptide, deletion or replacement mutants were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-M2AP.

The first residue of the MIC5 propeptide (leucine) plays a critical role in microneme trafficking

M2AP propeptide analysis indicated that residues near the N-terminus are important for trafficking. To test if this is also true for MIC5, we performed N-terminal deletion analyses of the 14 amino acid MIC5 propeptide. In the first step, we generated seven plasmid constructs containing serial deletions of 2 (Δ2), 4 (Δ4), 6 (Δ6), 8 (Δ8), 10 (Δ10), 12 (Δ12), and 14 (Δ14, MIC5Δpro) amino acids of the MIC5 propeptide (Fig. 5A) and transfected into MIC5KO parasites. Parasite populations stably expressing WT and deletion constructs were analyzed by IFA using antibodies against MIC5 and MIC10. Deletion of the first two amino acids of the MIC5 propeptide was sufficient to impair trafficking to the micronemes (Fig. 5B and C), indicating that similar to M2AP, the key residues are displayed near the N-terminus of the propeptide. Interestingly, the localization of MIC5 in trafficking defective parasites showed a strikingly different pattern from that seen previously with M2AP trafficking mutants. A small fraction of MIC5 co-localized with the late endosome marker VP1 (Fig 5D, upper panels), but most of the protein showed distinct localization that did not correspond to dense granules (Fig. 5D, lower panels) or ER (data not shown).

Figure 5.

N-terminal serial deletion analysis of MIC5 propeptide suggests that a leucine near the N-terminus is important for trafficking. A. Schematic representation and sequences of full-length and N-terminal serial deletion constructs of MIC5 propeptide. An arrow denotes the proteolytic cleavage site. B. Location of mature MIC5 in intracellular parasites was examined by IFA using anti-MIC5 and anti-MIC10 antibodies. Arrows denote the site where the mature MIC5 is retained in the secretory pathway in parasites that showed defective trafficking. Scale bar: 2 μM. C. Quantification of MIC5 and MIC10 colocalization. Bars represent SEM. ns, not statistically different from WT i.e., P>0.05, one sample t-test. *, P<0.05. D. Double immunolocalization of MIC5Δ2 parasites with anti-MIC5 and anti-VP1 or GRA4. Approximate positions of parasites are indicated by dash-lined ovals. E. Parasites stably transfected with full-length propeptide or deletion mutants were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MIC5.

Interestingly, deletion of an additional 2 amino acids (MIC5Δ4) resulted in restoration of correct microneme localization. Subsequent deletion mutants showed defective trafficking similar to the Δ14 (MIC5Δpro) mutant (Fig. 5B and C). Immunoblot analysis with anti-MIC5 antibodies showed that most of the MIC5 does not undergo proteolytic processing in trafficking-defective parasites (Δ2, Δ6, and Δ10) (Fig. 5E). Since processing of MIC5 likely occurs in the endosomal system (24), the lack of processing is consistent with arrest or diversion of mutant proteins prior to reaching the processing site in the endosomes.

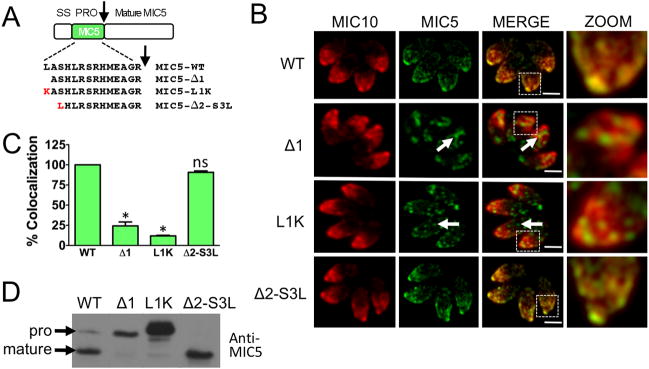

We noticed that both the wild-type MIC5 propeptide (MIC5-WT) and the MIC5Δ4 mutant that showed restored trafficking have a leucine is displayed at the N-terminus. To test the requirement for an N-terminal leucine, we created parasites expressing mutant MIC5 in which this residue was deleted (MIC5Δ1) or replaced with lysine (MIC5-L1K). MIC5 failed to co-localize with MIC10 in both of these parasite lines (Fig. 6B and C). To further confirm the importance of an N-terminal leucine, we made parasites expressing mutant MIC5 in which the first two residues of the propeptide were deleted and the third residue serine was replaced with leucine (MIC5Δ2-SL). These parasites showed extensive MIC5 colocalization with MIC10 (Fig. 6B and C) thus confirming that a terminal leucine is indeed necessary for correct targeting of MIC5. This was further confirmed by immunoblot analysis using anti-MIC5 antibodies (Fig. 6D). Very little processed MIC5 was observed in MIC5Δ1 and MIC5-L1K parasites, whereas efficient processing of MIC5Δ2-SL occurred. These findings are also consistent with trafficking defective mutants of MIC5 being arrested or diverted prior to reaching the processing site in the late endosomes.

Figure 6.

Fine mapping of MIC5 propeptide confirmed that an N-terminal leucine is important for trafficking. A. Schematic representation and sequences of full-length, deletion and replacement mutants of MIC5 propeptide. An arrow denotes the proteolytic cleavage site. B. Location of mature MIC5 in intracellular parasites was examined by IFA using anti-MIC5 and anti-MIC10 antibodies. Arrows denote the sites where the mature MIC5 is retained in intracellular parasites that showed defective trafficking. Scale bar: 2 μM. C. Quantification of MIC5 and MIC10 colocalization. Bars represent SEM. ns, not statistically different from WT i.e., P>0.05, one sample t-test. *, P<0.05. D. Parasites stably transfected with full-length propeptide or deletion mutants were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MIC5.

Valine and leucine are interchangeable in M2AP and MIC5 propeptides

Leucine and valine are closely related amino acids with side chains differing by only one methylene group. To test if valine and leucine can substitute for each other in M2AP and MIC5 propeptides, we made parasite cell lines in which valine of M2AP is replaced with leucine (M2AP-V3L) or leucine of MIC5 propeptide is replaced with valine (MIC5-L1V) (Fig. 7A). Results showed that M2AP-V3L and MIC5-L1V extensively co-localize with MIC10 (Fig. 7A and B) thus indicating that valine and leucine are largely interchangeable. Immunoblot analysis indicated that both M2AP-V3L and MIC5-L1V were processed similar to the respective wild-type proteins (Fig. 7D).

Figure 7.

Valine and leucine are largely interchangeable in M2AP and MIC5 propeptides. A. Schematic representation of plasmid constructs in which valine of M2AP propeptide is replaced with leucine and leucine of MIC5 propeptide is replaced with valine. The propeptide sequences along with mutated residues are also shown. B. Location of mature MIC5 and M2AP in intracellular parasites was examined by IFA using anti-M2AP or anti-MIC5 and anti-MIC10 antibodies. Scale bar: 2 μM. C. Quantification of M2AP or MIC5 and MIC10 colocalization. Bars represent SEM. ns, not statistically different from WT i.e., P>0.05, one sample t-test. *, P<0.05. C. Immunoblot analysis of M2AP-WT and M2AP-VL parasite lysates with anti-M2AP (left panel) or MIC5-WT and MIC5-LV parasite lysates with anti-MIC5 (right panel).

Aliphatic residues near the N-terminus of several disparate microneme propeptides are required for microneme targeting

As the propeptide deletion mapping analyses of M2AP and MIC5 indicated that a leucine or valine near the N-terminus is important for microneme targeting, we reexamined the microneme propeptide sequences of AMA1, MIC3 and EtMIC5. Interestingly, all three propeptide sequences contain leucine residues near the N-terminus (Fig. 8A). To determine if the leucine residues are important, we made parasite cell lines containing point mutations in AMA1, MIC3 and EtMIC5 and examined by IFA. Results showed that M2AP trafficking was at least partially impaired in all the mutant propeptide expressing parasites. The AMA1-L3K and EtMIC5-L2K mutants largely mislocalized to the endosomal system. The MIC3-L1K mutant targeted mostly to the micronemes but a minor subpopulation was mistargeted to the parasitophorous vacuole. Mis-trafficking of these mutants indicates that aliphatic residues at the N-terminus are important determinants of microneme targeting for several disparate proteins (Fig. 8B and C). Immunoblot analysis revealed correct processing of the mutant proteins, consistent with them encountering the propeptide processing protease despite their aberrant trafficking (Fig. 8D).

Discussion

T. gondii microneme proteins released in response to calcium-mediated signals are not only essential for parasite entry into host cells but also for gliding motility. Accordingly many parasite cell lines deficient in microneme proteins such as MIC2, M2AP, AMA1, MIC8 are severely impaired in invasion and virulence in mouse infections. Hence studying the synthesis, transport, storage, secretion and functioning of microneme proteins might reveal new players that could act as novel targets for intervention. Recent studies on microneme trafficking in T. gondii have revealed that cytoplasmic domains of transmembrane microneme proteins do not necessarily contain sufficient signals for trafficking (22). This view is also supported by the findings that propeptide domains play a crucial role in correct targeting of microneme proteins (19–21,29). In this study we take a step further and show that propeptides within T. gondii and also in the related parasite Eimeria tenella can substitute for one another and hence appear to function in a context independent manner. We also define at the single residue level that aliphatic amino acids near the N-terminus of microneme propeptides are crucial for correct targeting to the micronemes.

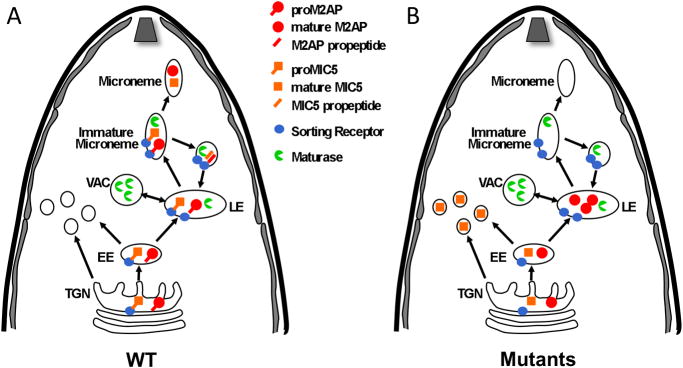

We found that the fates of M2AP and MIC5 are different in trafficking defective parasites, suggesting that propeptides contribute to trafficking at distinct places within the secretory pathway. Several studies have shown that T. gondii regulated secretory pathways to the rhoptries and micronemes involve the parasite endosomal system including early and late endosomes (14,19,30,31). As depicted in a working model of propeptide based trafficking (Fig. 9), the M2AP propeptide appears to function relatively late in the trafficking pathway since M2AP propeptide mutants successfully navigate the ER, Golgi, trans-Golgi network (TGN) and early endosomes but are arrested in the late endosomes (19) prior to reaching the micronemes (14). In contrast, trafficking signals within the MIC5 propeptide appear to be used earlier in the secretory system since trafficking defective mutants are arrested or diverted prior to reaching the late endosomes based on immunolocalization within distinct punctate structures and the absence of endosomal proteolytic processing. Unlike MIC5, M2AP has a transmembrane binding partner, MIC2, which provides sufficient targeting information to navigate the early secretory organelles including the ER and Golgi (15). Thereafter, M2AP appears to guide the complex through the early endosomes to the late endosomes where the M2AP propeptide is required for entry into the micronemes (19). Since MIC5 does not have a known binding partner, it likely uses its propeptide earlier in the system, thus explaining the diversion of such mutants to an alternative site(s). MIC3 is distinct case since its trafficking to the micronemes is independent of its transmembrane partner MIC8 (12) and MIC3 propeptide mutants are diverted to the parasitophorous vacuole, presumably via the dense granules ((21) and Fig. 8B). These findings, together with the extensive interchangeability of microneme propeptides, suggests that propeptides confer a shared trafficking function albeit at several distinct sites within the secretory system, with the site of mutant diversion or retention reflecting the earliest propeptide-dependent step in the pathway.

Figure 9.

A working model for propeptide based targeting of M2AP and MIC5 in Toxoplasma. A. Wild-type proM2AP and proMIC5 pass-through the Trans-Golgi Network (TGN), Early Endosomes (EE) and Late Endosomes (LE). proMICs interact with hypothetical sorting receptors In the TGN, EE, and LE that guide them into a budding immature microneme where propeptide cleavage is performed by maturase(s). The sorting receptor is then recycled back to the LE to pick up more cargo. B. Mutant proM2AP is guided through the early secretory organelles by its binding partner MIC2 (not shown) but is arrested in the LE because of a failure to interact with the sorting receptor. Mutant proM2AP is still processed to some extent by maturases in the LE. However, mutant proMIC5 does not have a binding partner to guide it to LE and hence is not processed by maturases in the LE or immature microneme. Instead it is diverted to punctate structures that are distinct from the endosomal system.

Two principal models have been proposed to explain how propeptides facilitate targeting to the regulated secretory pathway of eukaryotic cells. The first model, “sorting by retention” argues that propeptide cleavage triggers a conformational shift in the mature protein, thus inducing aggregation under the mildly acidic conditions of the immature secretory granule (32). Aggregation promotes retention in the maturing granule whereas proteins not intended for regulated secretion are diverted elsewhere. Much of the data in support of this model comes from the insulin field where it has been shown that processing of proinsulin dramatically alters its structure and that mature insulin is retained better in maturing granules than the proinsulin precursor. The second model, “sorting for entry” involves the use of sorting receptors that guide the selective cargo to the regulated secretory pathway. This model is based in part on the discovery of several putative metazoan sorting receptors in the regulated pathway including carboxypeptidase E (33) and granins (34,35). Also, a recent study showed that sorting of prohormone convertase (PC)1/3 to dense core secretory granules is mediated by a hydrophobic patch within an α-helix near the C-terminus of the protein that helps the protein to associate with the membrane (36). Interestingly, a leucine residue (L745) within the hydrophobic patch is critical for this interaction and mutation of this residue abolishes sorting of PC1/3 to dense core secretory vesicles.

Previous work showing that propeptide cleavage is not necessary for microneme targeting (19,21) and our current finding that propeptide cleavage is not sufficient for M2AP targeting to the micronemes (Fig. 3E) is inconsistent with a sorting by retention model. On the other hand, the involvement of a sorting by entry/receptor mechanism in microneme trafficking is attractive for two reasons. First, propeptides reside in the lumen of secretory compartments and do not have direct access to the cytoplasm where much of the sorting machinery exists. Sorting receptors are designed to couple luminal cargo with the cytoplasmic sorting machinery that executes vesicular trafficking. Second, recognition by a sorting receptor could explain the discrete nature of the propeptide sorting element, which we show involves aliphatic residues at or near the N-terminus of the microneme propeptide. Such proximity to the N-terminus may impart solvent and receptor accessibility of these key residues. Finally, engagement of sorting receptors at distinct sites in the secretory pathway could help explain the different fates of microneme propeptide mutants (Fig. 9).

Two of the best-characterized cargo receptors in higher eukaryotes include the mannose-6-phosphate receptor (MPR) (37) and sortilin (38,39), which are involved in the trafficking of lysosomal enzymes from the TGN to the early endosome. The Iuminal domain of sortilin interacts with the cargo, while the cytoplasmic domain interacts with adapter proteins of the vesicular trafficking machinery. Crystal structure analysis of sortilin in association with a cargo protein, neurotensin, has shown that a C-terminal tripeptide motif, Tyr-Ile-Leu, of neurotensin is important for the interaction and that the leucine residue fits into the hydrophobic pocket of the receptor (40). Vacuolar sorting receptors (VSR) (41–43) in plants function in protein trafficking from TGN to vacuole. Studies on VSR-based trafficking of cargo proteins in plants have shown that vacuolar targeting signals reside within propeptides of the cargo and the aliphatic residues isoleucine and leucine are critical for the interaction with VSRs (43,44).

The T. gondii genome does not encode a MPR but contains a single sortilin gene, TgSortilin (TgME49_09160), and two putative VSRs, TgVSR1 (TgME49_024710) and TgVSR2 (TgME49_112860). Thus, T. gondii possesses both animal-like and plantlike cargo receptors (45). A preliminary analysis of these putative cargo receptors revealed that TgSortilin and TgVSR2 are expressed in T. gondii tachyzoites based on mRNA and protein analysis, but TgVSR1 was not detected (data not shown). TgSortilin and TgVSR2 both reside in late endosomes where they colocalize with VP1. Repeated attempts to disrupt TgSortilin were not successful implying that it is an essential gene. Targeted disruption of TgVSR2 did not affect microneme protein trafficking indicating a distinct or redundant role for this putative cargo receptor. Additional non-canonical sorting receptors might also exist. Further studies will be necessary to determine the role of TgSortilin or other yet-to-be-identified cargo receptors in microneme propeptide sorting.

Since no studies have been performed in other apicomplexan parasites regarding the role of propeptides in microneme protein trafficking, it remains unclear whether these elements play a conserved role in parasites related to T. gondii. Our finding that the EtMIC5 propeptide can function in microneme protein transport in T. gondii suggests that functional conservation exists at least within the coccidian branch of the Apicomplexa. In addition to functioning in microneme protein trafficking, propeptides are emerging as important determinants of trafficking to apicomplexan rhoptries (46,47) and export of Plasmodium proteins into the cytosol of infected erythrocytes (47–50). Although it remains to be determined whether conserved mechanisms are involved, our findings suggest that the key residues necessary for propeptide-based trafficking can be highly discrete and therefore non-recognizable as conserved motifs. Accordingly, determining the molecular basis of propeptide trafficking to the rhoptries or erythrocyte cytosol might also require fine mapping of the residues involved.

Materials and Methods

Parasite culture

T. gondii tachyzoites were maintained by passage through human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. The normal growth medium consisted of DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM L-glutamine and 50 μg/ml penicillin streptomycin. Purification of parasites by filtration was performed as described previously (23).

Plasmid constructs

Primers used in generating plasmid constructs described in this section are listed in Table S1–S7. To obtain AMA1-M2AP, MIC3-M2AP plasmid constructs, the signal sequence and propeptide region of AMA1 and MIC3 were amplified from cDNA library of RH strain parasites by PCR and fused with M2AP mature protein sequence by overlap extension PCR. The final PCR products were digested with NsiI, PacI and directionally cloned downstream of M2AP promoter in M2AP-CV described previously (16). To make EtMIC5-M2AP and M2AP-SCR, M2AP signal peptide fused with either EtMIC5 propeptide or scrambled M2AP propeptide sequences were obtained as dsDNA molecules (IDT), amplified by PCR and fused with M2AP mature ORF by overlap extension PCR. The resulting PCR products were then digested with NsiI, PacI and cloned into M2AP-CV. All M2AP and MIC5 propeptide deletion, mutation and replacement constructs were made using Quik-changeII XL site directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the parent plasmids, M2AP-CV or MIC5-CV (24) were denatured and two complementary primers (forward and reverse) containing the desired mutation were allowed to anneal. The primer extension was performed using PfuUltra DNA polymerase and the methylated or hemimethylated parent plasmid DNA was digested with DpnI. The newly synthesized mutated plasmid DNA molecule was transformed into competent cells for nick repair. Plasmid constructs AMA1-L3K, MIC3-L1K and EtMIC5-L2K were also made by site directed mutagenesis technique as described above using parent plasmids AMA1-M2AP, MIC3-M2AP and EtMIC5-M2AP. All constructs were verified by restriction digestion and sequencing.

Stable transformation

Plasmid constructs were electroporated into T. gondii tachyzoites according to established protocols (25) with a combination of wild-type or mutated propeptide construct (50 μg), and plasmid containing selectable marker TUB-DHFR (10 μg) and added onto HFF monolayer. Parasite populations stably expressing transfected construct were selected by culturing in presence of 1 μM pyrimethamine (26).

Immunoblotting

Parasite lysates were heated at 100°C for 5 min in SDS-PAGE sample buffer with 2% 2-mercaptoethanol and resolved on 10% or 12.5% gels. Proteins from the gel were transferred to PVDF membranes using a semidry transfer apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) at 16 V for 30 min. After blocking with 10% (w/v) skim milk powder in PBS, membranes were treated with primary antibody rabbit-rM2AP (16) or rabbit-rMIC5 (27) for 1 h. Membranes were then washed and incubated with secondary antibodies, goat-anti rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories, West Grove, PA). After washing, membranes were treated with SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce Chemical) and exposed to X-ray film.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Immunofluorescence staining of intracellular parasites was performed according to previously described procedures (23). Briefly, freshly lysed parasites were added onto confluent monolayer of HFF cells in 8-well chamber slides. About 16 h post-infection, slides were washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and fixed with 4% formaldehyde and 0.025% glutaraldehyde for 20 min. Fixed slides were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min and blocked with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). After 30 min blocking, primary antibodies diluted in 1% FBS/1% normal goat serum (NGS) were added onto the slides. The primary antibodies used were: rat anti-MIC10, rabbit anti-M2AP, rabbit anti-MIC5, rat anti-M2AP and rabbit anti-VP1. After 1 h, slides were washed three times with 1% FBS/1% NGS/PBS and secondary Alexa fluorophore conjugated antibodies were added. Secondary antibodies used include: Alexa Fluor-594- or Alexa Fluor-488-conjugated goat anti-rat or goat anti-rabbit (Molecular Probes). After 1 h, slides were washed three times and mounted using Mowiol (Sigma-Aldrich). Slides were viewed using an Axio observer Z1 (Zeiss) inverted wide field fluorescent microscope, and digital images were captured as Z-stack series using an AxioCam MRm (Zeiss) charge-coupled device camera. The images were then deconvolved with a regularized inverse filter algorithm and a region around the vacuole (four parasites per vacuole) in the deconvolved image was selected and Pearson’s colocalization coefficient was determined using Axiovision software (Zeiss).

Supplementary Material

A. Schematic representation and sequences of the full-length and distal N-terminal serial deletion constructs of M2AP propeptide. The proteolytic cleavage site is indicated by an arrow. B. Location of mature M2AP in intracellular parasites was examined by IFA using anti-M2AP and anti-MIC10 antibodies. Arrows denote the site where the mature M2AP is retained in the secretory pathway in parasites that showed defective trafficking. Scale bar: 2 μM. C. Quantification of M2AP and MIC10 colocalization. Bars represent SEM. ns, not statistically different from WT i.e., P>0.05, one sample t-test. *, P<0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tracey Schultz for expert technical assistance, My-Hang Huynh for critically reading the manuscript, and Stanislas Tomavo for sharing unpublished data. This work was supported by grant AI046675 from the National Institutes of Health (VBC) and American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship (RYG).

References

- 1.Dikeakos JD, Reudelhuber TL. Sending proteins to dense core secretory granules: still a lot to sort out. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:191–196. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones JL, Kruszon-Moran D, Wilson M, McQuillan G, Navin T, McAuley JB. Toxoplasma gondii infection in the United States: seroprevalence and risk factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:357–65. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sibley LD. Intracellular parasite invasion strategies. Science. 2004;304:248–53. doi: 10.1126/science.1094717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dobrowolski JM, VC, Sibley LD. Participation of myosin in gliding motility and host cell invasion by Toxoplasma gondii. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:163–173. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5671913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carruthers VB, Giddings OK, Sibley LD. Secretion of micronemal proteins is associated with Toxoplasma invasion of host cells. Cell Microbiol. 1999;1:225–235. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.1999.00023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soldati D, Dubremetz JF, Lebrun M. Microneme proteins: structural and functional requirements to promote adhesion and invasion by the apicomplexan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Int J Parasitol. 2001;31:1293–1302. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cerede O, Dubremetz JF, Bout D, Lebrun M. The Toxoplasma gondii protein MIC3 requires pro-peptide cleavage and dimerization to function as adhesin. EMBO J. 2002;21:2526–36. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.11.2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carruthers VB, Moreno SN, Sibley LD. Ethanol and acetaldehyde elevate intracellular [Ca2+] and stimulate microneme discharge in Toxoplasma gondii. Biochem J. 1999;342 ( Pt 2):379–386. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huynh MH, Carruthers VB. Toxoplasma MIC2 is a major determinant of invasion and virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e84. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carruthers VB. Host cell invasion by the opportunistic pathogen Toxoplasma gondii. Acta Trop. 2002;81:111–122. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(01)00201-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meissner M, Reiss M, Viebig N, VC, Toursel C, Tomavo S, Ajioka J, Soldati D. A family of transmembrane microneme proteins of Toxoplasma gondii contain EGF-like domains and function as escorters. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:563–574. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.3.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler H, Herm-Gotz A, Hegge S, Rauch M, Soldati-Favre D, Frischknecht F, Meissner M. Microneme protein 8 - a new essential invasion factor in Toxoplasma gondii. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:947–956. doi: 10.1242/jcs.022350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jewett TJ, Sibley LD. The Toxoplasma proteins MIC2 and M2AP form a hexameric complex necessary for intracellular survival. J Biol Chem. 2003;11:885–894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312590200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parussini F, Coppens I, Shah PP, Diamond SL, Carruthers VB. Cathepsin L occupies a vacuolar compartment and is a protein maturase within the endo/exocytic system of Toxoplasma gondii. Mol Microbiol. 2010;76:1340–1357. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07181.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huynh MH, Rabenau KE, Harper JM, Beatty WL, Sibley LD, VC Rapid invasion of host cells by Toxoplasma requires secretion of the MIC2-M2AP adhesive protein complex. EMBO J. 2003;22:2082–2090. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rabenau KE, Sohrabi A, Tripathy A, Reitter C, Ajioka JW, Tomley FM, VC TgM2AP participates in Toxoplasma gondii invasion of host cells and is tightly associated with the adhesive protein TgMIC2. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41:537–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Cristina M, Spaccapelo R, Soldati D, Bistoni F, Crisanti A. Two conserved amino acid motifs mediate protein targeting to the micronemes of the apicomplexan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7332–7341. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.19.7332-7341.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reiss M, Viebig N, Brecht S, Fourmaux MN, Soete M, Di Cristina M, Dubremetz JF, Soldati D. Identification and characterization of an escorter for two secretory adhesins in Toxoplasma gondii. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:563–578. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.3.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harper JM, Huynh MH, Coppens I, Parussini F, Moreno S, Carruthers VB. A cleavable propeptide influences Toxoplasma infection by facilitating the trafficking and secretion of the TgMIC2-M2AP invasion complex. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:4551–4563. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-01-0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brydges SD, Harper JM, Parussini F, Coppens I, Carruthers VB. A transient forward-targeting element for microneme-regulated secretion in Toxoplasma gondii. Biol Cell. 2008;100:253–264. doi: 10.1042/BC20070076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El Hajj H, Papoin J, Cerede O, Garcia-Reguet N, Soete M, Dubremetz JF, Lebrun M. Molecular signals in the trafficking of Toxoplasma gondii protein MIC3 to the micronemes. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:1019–1028. doi: 10.1128/EC.00413-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheiner L, Santos JM, Klages N, Parussini F, Jemmely N, Friedrich N, Ward GE, Soldati-Favre D. Toxoplasma gondii transmembrane microneme proteins and their modular design. Mol Microbiol. 2010;77:912–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07255.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carruthers VB, Sibley LD. Mobilization of intracellular calcium stimulates microneme discharge in Toxoplasma gondii. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:421–428. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brydges SD, Zhou XW, Huynh MH, Harper JM, Mital J, Adjogble KD, Daubener W, Ward GE, Carruthers VB. Targeted deletion of MIC5 enhances trimming proteolysis of Toxoplasma invasion proteins. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:2174–2183. doi: 10.1128/EC.00163-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soldati D, Boothroyd JC. Transient transfection and expression in the obligate intracellular parasite, Toxoplasma gondii. Science. 1993;260:349–351. doi: 10.1126/science.8469986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donald RGK, Roos DS. Stable molecular transformation of Toxoplasma gondii: A selectable DHFR-TS marker based on drug resistance mutations in malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11703–11707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brydges SD, Sherman GD, Nockemann S, Loyens A, Daubener W, Dubremetz JF, Carruthers VB. Molecular characterization of TgMIC5, a proteolytically processed antigen secreted from the micronemes of Toxoplasma gondii. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;111:51–66. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(00)00296-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miranda K, Pace DA, Cintron R, Rodrigues JC, Fang J, Smith A, Rohloff P, Coelho E, de Haas F, de Souza W, Coppens I, Sibley LD, Moreno SN. Characterization of a novel organelle in Toxoplasma gondii with similar composition and function to the plant vacuole. Mol Microbiol. 2010;76:1358–1375. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07165.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Binder EM, Lagal V, Kim K. The prodomain of Toxoplasma gondii GPI-anchored subtilase TgSUB1 mediates its targeting to micronemes. Traffic. 2008;9:1485–1496. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00774.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoppe HC, Ngo HM, Yang M, Joiner KA. Targeting to rhoptry organelles of Toxoplasma gondii involves evolutionarily conserved mechanisms. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:449–456. doi: 10.1038/35017090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ngo HM, Yang M, Paprotka K, Pypaert M, Hoppe H, Joiner KA. AP-1 in Toxoplasma gondii mediates biogenesis of the rhoptry secretory organelle from a post-Golgi compartment. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5343–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208291200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arvan P, Halban PA. Sorting ourselves out: seeking consensus on trafficking in the beta-cell. Traffic. 2004;5:53–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cool DR, Normant E, Shen F, Chen HC, Pannell L, Zhang Y, Loh YP. Carboxypeptidase E is a regulated secretory pathway sorting receptor: genetic obliteration leads to endocrine disorders in Cpe(fat) mice. Cell. 1997;88:73–83. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81860-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Natori S, Huttner WB. Chromogranin B (secretogranin I) promotes sorting to the regulated secretory pathway of processing intermediates derived from a peptide hormone precursor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4431–4436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim T, Tao-Cheng JH, Eiden LE, Loh YP. Chromogranin A, an “on/off” switch controlling dense-core secretory granule biogenesis. Cell. 2001;106:499–509. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00459-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dikeakos JD, Di Lello P, Lacombe MJ, Ghirlando R, Legault P, Reudelhuber TL, Omichinski JG. Functional and structural characterization of a dense core secretory granule sorting domain from the PC1/3 protease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7408–7413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809576106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lobel P, Fujimoto K, Ye RD, Griffiths G, Kornfeld S. Mutations in the cytoplasmic domain of the 275 kd mannose 6-phosphate receptor differentially alter lysosomal enzyme sorting and endocytosis. Cell. 1989;57:787–796. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90793-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Canuel M, Korkidakis A, Konnyu K, Morales CR. Sortilin mediates the lysosomal targeting of cathepsins D and H. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;373:292–297. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Canuel M, Libin Y, Morales CR. The interactomics of sortilin: an ancient lysosomal receptor evolving new functions. Histol Histopathol. 2009;24:481–492. doi: 10.14670/HH-24.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quistgaard EM, Madsen P, Groftehauge MK, Nissen P, Petersen CM, Thirup SS. Ligands bind to Sortilin in the tunnel of a ten-bladed beta-propeller domain. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:96–98. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kirsch T, Paris N, Butler JM, Beevers L, Rogers JC. Purification and initial characterization of a potential plant vacuolar targeting receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3403–3407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kirsch T, Saalbach G, Raikhel NV, Beevers L. Interaction of a potential vacuolar targeting receptor with amino- and carboxyl-terminal targeting determinants. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:469–474. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.2.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ahmed SU, Rojo E, Kovaleva V, Venkataraman S, Dombrowski JE, Matsuoka K, Raikhel NV. The plant vacuolar sorting receptor AtELP is involved in transport of NH(2)-terminal propeptide-containing vacuolar proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:1335–1344. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsuoka K, Nakamura K. Large alkyl side-chains of isoleucine and leucine in the NPIRL region constitute the core of the vacuolar sorting determinant of sporamin precursor. Plant Mol Biol. 1999;41:825–835. doi: 10.1023/a:1006357413084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gajria B, Bahl A, Brestelli J, Dommer J, Fischer S, Gao X, Heiges M, Iodice J, Kissinger JC, Mackey AJ, Pinney DF, Roos DS, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, Wang H, Brunk BP. ToxoDB: an integrated Toxoplasma gondii database resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D553–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bradley PJ, Boothroyd JC. The pro region of Toxoplasma ROP1 is a rhoptry-targeting signal. Int J Parasitol. 2001;31:1177–1186. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Richard D, Kats LM, Langer C, Black CG, Mitri K, Boddey JA, Cowman AF, Coppel RL. Identification of rhoptry trafficking determinants and evidence for a novel sorting mechanism in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000328. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chang HH, Falick AM, Carlton PM, Sedat JW, DeRisi JL, Marletta MA. N-terminal processing of proteins exported by malaria parasites. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2008;160:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Osborne AR, Speicher KD, Tamez PA, Bhattacharjee S, Speicher DW, Haldar K. The host targeting motif in exported Plasmodium proteins is cleaved in the parasite endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2010;171:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Russo I, Babbitt S, Muralidharan V, Butler T, Oksman A, Goldberg DE. Plasmepsin V licenses Plasmodium proteins for export into the host erythrocyte. Nature. 2010;463:632–636. doi: 10.1038/nature08726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A. Schematic representation and sequences of the full-length and distal N-terminal serial deletion constructs of M2AP propeptide. The proteolytic cleavage site is indicated by an arrow. B. Location of mature M2AP in intracellular parasites was examined by IFA using anti-M2AP and anti-MIC10 antibodies. Arrows denote the site where the mature M2AP is retained in the secretory pathway in parasites that showed defective trafficking. Scale bar: 2 μM. C. Quantification of M2AP and MIC10 colocalization. Bars represent SEM. ns, not statistically different from WT i.e., P>0.05, one sample t-test. *, P<0.05.