Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to clarify the association of the angiotensinogen gene (AGT) with insulin sensitivity using SNP and haplotype analyses in a Caucasian cohort.

Material and Methods

A candidate gene association study was conducted in Caucasians with and without hypertension (N=449). Seventeen single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of the AGT gene and their haplotypes were analyzed for an association with HOMA-IR. Multivariate regression model accounting for age, gender, BMI, hypertension status, study site, and sibling relatedness was used to test the hypothesis.

Results

Nine of the seventeen SNPs were significantly associated with lower HOMA-IR levels. Homozygous minor allele carriers of the most significant SNP rs2493134 (GG), a surrogate for the gain of function mutation rs699 [AGT p.M268T], had significantly lower HOMA-IR levels (p=0.0001) than heterozygous or homozygous major allele carriers (GC, AA). Direct genotyping of rs699 in a subset of the population showed similar results with minor allele carriers exhibiting significantly decreased HOMA-IR levels (p=0.003). Haplotype analysis demonstrated that haplotypes rs2493137A|rs5050A|rs3789678G|rs2493134A and rs2004776G|rs11122576A|rs699T|rs6687360G were also significantly associated with HOMA-IR (p=0.0009, p=0.02) and these results were driven by rs2493134 and rs699.

Conclusion

This study confirms an association between the AGT gene and insulin sensitivity in Caucasian humans. Haplotype analysis extends this finding and implicates SNPs rs2493134 and rs699 as the most influential. Thus, AGT gene variants, previously shown to be associated with AGT levels, are also associated with insulin sensitivity; suggesting a relationship between the AGT gene, AGT levels, and insulin sensitivity in humans.

Keywords: insulin resistance, hypertension, angiotensinogen, genetics

Introduction

Angiotensinogen (AGT) is the initial component of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and a precursor to both angiotensin I (AngI) and angiotensin II (AngII). Variants of the AGT gene are associated with plasma angiotensinogen levels, hypertension, and adrenal and renal blood flow [1-3]; likely through the downstream effects of AGT on AngII. A possible role for AGT and AngII in the development of altered glucose metabolism is unclear. Pharmacologic blockade of the RAAS exhibits conflicting results demonstrating a decrease in the incidence of new onset type 2 diabetes in some [4,5], but not other studies [6]. Further, gene association studies fail to clarify this issue reporting both positive and negative associations for genes of the RAAS with insulin resistance (IR) and insulin sensitivity [7-10].

It is possible that studies analyzing components of RAAS with glucose metabolism conflict due to the heterogeneity of the populations studied and the inconsistent measurements of IR, blood pressure (BP), and type 2 diabetes. To address this possibility, we took advantage of a cohort where influential confounders (medication, activity, diet) were controlled. We examined whether single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of the AGT gene are associated with IR as determined by HOMA-IR in a Caucasian cohort. To our knowledge, this is the first study that evaluates the relationship between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) representing coverage of the entire AGT gene and IR. To extend these observations we also conducted haplotype analyses.

Research Design and Methods

Population

The 449 Caucasian participants studied were part of the Hypertensive Pathotype (HyperPATH) cohort, a dataset of participants with and without mild hypertension. Four international centers contributed to this dataset: Brigham and Women's Hospital (Boston, MA, USA) (N=155), University of Utah Medical Center (Salt Lake City, UT,USA) (N=179), Hospital Broussais (Paris, France) (N=84), and Vanderbilt University (Nashville, TN. USA) (N=31) [11-13]. Individuals included in this analysis were participants with measured fasting glucose values, fasting insulin values, and genotyped for variants of the AGT gene. Individuals with and without hypertension were included to examine the relationship between the AGT gene and IR within a range of metabolic risk. Further, we examined whether hypertension status affected the genotype-phenotype relationship.

Phenotype Protocol

Hypertension was defined as a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥100 mmHg on no medications, DBP≥90 mmHg on one anti-hypertensive medication, or the use of two or more antihypertensive medications at the time of screening [11-13]. Normotensives, in addition to having blood pressure (BP) less than 140/90, reported no first-degree relatives diagnosed with hypertension before age 60 yr [11]. Non-diabetic participants (fasting glucose <126mg/dl, 2 hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) glucose <200mg/dl, no oral hypoglycemic agents) were excluded in this analysis due to small sample size. All participants were placed on an isocaloric high salt diet (200mmol/d sodium, 100mmol/d potassium, 1000mmol/d calcium) for 5 days prior to study to control for known effects of salt on measurements of RAAS and insulin sensitivity [14]. On the final day of the diet, participants were admitted to the General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) and remained fasting and supine overnight. Participants were washed-off of anti-hypertension medications as previously described to minimize the effects of these medications on study outcome measurements [11-13].

All inclusion and exclusion criteria for the HyperPath protocol is described elsewhere [11- 13]. In brief, participants with known or suspected secondary hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke, overt renal insufficiency (serum creatinine >1.5mg/dl), psychiatric illness, current oral contraceptive use, current tobacco/illicit drug use or moderate alcohol use were excluded. Participants with abnormal electrolyte or thyroid/liver function tests or electrocardiographic evidence of heart block, ischemia, or prior coronary events at the screening exam were excluded. All participants were between the ages of 18 and 65 years [11-13].

Baseline systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial blood pressures were taken as the mean of three consecutive readings (by Dinamap; Critikon, Tampa, Fl.) separated by 5 minutes each. Plasma glucose, serum insulin, and lipids levels were measured after an eight hour fast and collected between 08:00 and 09:00. Serum insulin, glucose, and lipids were measured as previously described [11]. HOMA-IR was calculated as (fasting glucose mmol X fasting insulin in mU/mL)/22.5) [15].

The HyperPath project was approved by the institutional review boards (IRB) of each participating site. All participants were recruited through IRB approved advertisements in the general population and informed consent was obtained prior to participant enrollment.

Outcome Measurement

The primary phenotype, IR as measured by HOMA-IR was initially assessed in the population.

Genotyping

DNA was extracted as previously described [2, 3]. Genotyping was conducted using the Illumina Bead Station GoldenGate platform. Sixteen tagging SNPs were identified from HapMap (Phase II, November 2008) using the chromosomal co-ordinates chr1:228,904,892-228,916,564 and including 5 kb flanking regions. Sixteen SNPs captured 100% of the common HapMap Caucasian variation in this region defined as minor allele frequencies >0.1 at R2>0.9 [16]. SNP rs2493134 was used as a surrogate for the well known AGT SNP rs699 [p.M268T].

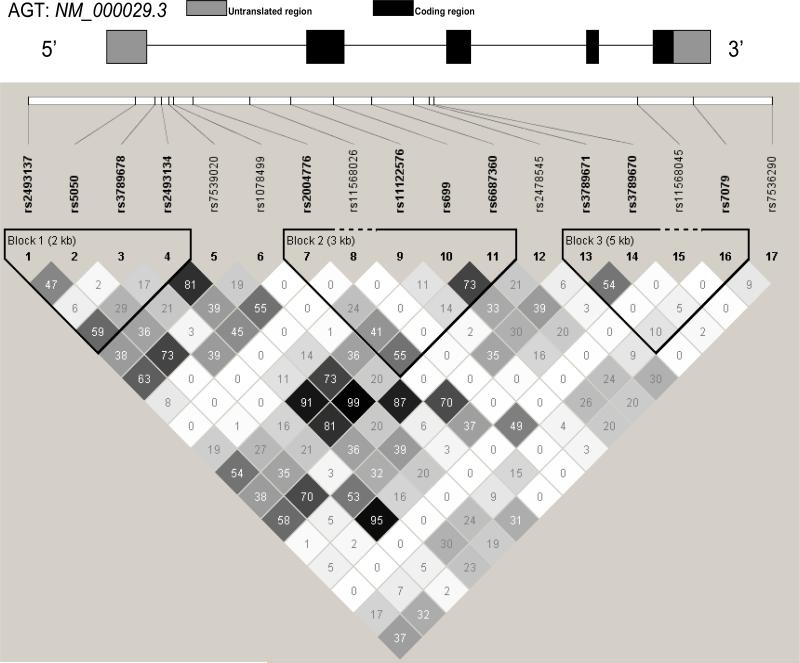

Additionally, a subset of the study population (N=385) were genotyped for rs699. This genotyping was conducted in an earlier HyperPATH genotyping sequence using Applied Biosystems (ABI) 3100 genetic analyzer. Genotypes were called using the Genescan and Genotyper software packages (ABI) [1]. Analyses of rs699 and rs2493134 were compared to evaluate the appropriateness of rs2493134 as a marker for rs699 in the larger population. The linkage disequilibrium (LD) plot of AGT SNPs for this study demonstrates strong LD between rs2493134 and rs699 (R2=.9, Figure 1) indicating rs2493134 and rs699 are inherited together and rs2493134 is an appropriate marker for rs699 in the larger cohort.

Figure 1. Linkage Disequilibrium Plot of 17 SNPs.

Numbers represent R2 values. Population includes participants with and without hypertension. SNP location along gene was determined using the NM_000029.3 AGT reference sequence.

All genotyped SNPs had a completion rate of greater than 95%. All SNPs conformed to Hardy-Weinberg expectations (HWE) in the study population. Further, SNP allele frequencies did not differ by site (p>0.05 for all SNPs tested via chi-square analysis). Repeat genotyping for 10% of the SNPs demonstrated concordance with the original genotype call.

The AGT variants are numbered using the Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) recommendations [17]. In Table 2, variants are numbered at the cDNA level. Position +1 corresponds to the A of the ATG translation initiation codon located at nucleotide 114 in the NM_000029.3 AGT reference sequence. Hence, rs699 with cDNA label c.803T>C and protein label p.M268T is identical to the previously described variant 4072T>C (cDNA) and M235T (protein label). The earlier reported naming of 4072T>C and M235T started numbering from the beginning of the mature peptide creating the difference between labels [18].

Table 2. Sixteen SNPs analyzed for association with log HOMA-IR values.

Minor allele frequencies did not differ significantly between study sites. SNP location was determined using the NM_000029.3 AGT reference sequence.

| # | Polymorphism | Location: cDNA NM_000029.3 | Amino Acid Change | MAF† | Log HOMA-IR p values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | rs2493137 | Upstream T>C | - | 0.31 | 0.01* |

| 2 | rs5050 | c.-58A>C | - | 0.17 | 0.03* |

| 3 | rs3789678 | c.-4+350G>A | - | 0.14 | 0.7 |

| 4 | rs2493134 | c.-4+473A>G | - | 0.44 | 0.0001** |

| 5 | rs7539020 | c.-4+642G>A | - | 0.40 | 0.005* |

| 6 | rs1078499 | c.-4+736T>C | - | 0.22 | 0.007* |

| 7 | rs2004776 | c.-4+11306G>A | - | 0.28 | 0.02* |

| 8 | rs11568026 | c.-3-924T>C | - | 0.00 | Monomorphic |

| 9 | rs11122576 | c. -3-80A>G | - | 0.08 | MAF<0.10 |

| 10 | rs699 | c. 803T>C | p.Met268Thr (M235T) | 0.42 | 0.0003** |

| 11 | rs6687360 | c.856+749G>A | - | 0.40 | 0.0003** |

| 12 | rs2478545 | c.856+1620C>T | - | 0.21 | 0.01* |

| 13 | rs3789671 | c.857-1854C>A | - | 0.22 | 0.1 |

| 14 | rs3789670 | c. 857-1768G>A | - | 0.13 | 0.07 |

| 15 | rs11568045 | c.1270_408A>C | - | 0.00 | Monomorphic |

| 16 | rs7079 | c.556C>A | - | 0.31 | 0.4 |

| 17 | rs7536290 | Downstream A>G | - | 0.15 | 0.2 |

Data are adjusted for age, gender, BMI, and hypertension status

p value <0.05

p value <0.004

MAF= minor allele frequency.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute; Cary N.C.). HWE testing was performed for each SNP using a chi-square test. Pairwise linkage (D’ and R2) was estimated using Haploview. A mixed effect linear regression (PROC MIXED) with all phenotypes and individual SNPs was performed accounting for relatedness between participants and adjusted for age, gender, body mass index (BMI), hypertension status and study site. The natural-log of HOMA-IR was used as the primary phenotype of interest. Both HOMA-IR and fasting insulin levels were log transformed to meet the normality assumptions of the regression model. HOMA-IR and fasting insulin estimates represented in the figures were untransformed to insure results were easily interpreted within a clinical perspective. Error is represented as 95% confidence intervals. Haplotypes were constructed using the Haploview program and an association of each haplotype with HOMA-IR was assessed using PLINK [19]. Plink estimates haplotype frequencies via the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm, computing global and haplotype-specific score statistics for tests of association between a trait and haplotype weighted by their posterior possibility. Since, PLINK is unable to account for relatedness, the haplotype analysis was conducted in unrelated individuals only. All statistical tests were 2 sided. Nominal significance is indicated for p<0.05. A Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons is conservative due to the LD between SNPS of the AGT gene [1]. However, significance at the Bonferroni-corrected level of 0.004(0.05/14=0.004) is indicated.

Results

Population Characteristics

Population characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Seventy one percent of the population had hypertension. Seventeen percent of the total population had impaired fasting glucose according to ADA criteria (fasting glucose ≥100mg/dl) [20]. Individuals with hypertension were more likely to have impaired fasting glucose when compared to normotensives. As expected, individuals with hypertension had significantly higher fasting glucose values, greater body mass index (BMI), higher triglyceride and total cholesterol levels, and elevated blood pressure than individuals without hypertension.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of the HyperPath Cohort by Hypertension Status.

| Baseline Characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| NTN | HTN | p value | |

| N=132 | N=317 | ||

| Age(years) | 39.07±11.07 | 48.60±8.07 | <0.0001* |

| Females [N(%)] | 67(50.76) | 130(41.01) | 0.06 |

| BMI(kg/m2) | 25.08±3.83 | 28.04±3.81 | <0.0001* |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 85.25±10.74 | 90.78±11.19 | <0.0001* |

| Fasting insulin(mg/dl) | 10.4±4.89 | 9.79±5.72 | <0.0001* |

| Impaired fasting glucose (≥100mg/dL) [N (%)] | 11(8.3%) | 67(21.14%) | <0.0001* |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | 109.48±11.05 | 145.58±20.24 | <0.0001* |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | 65.74±8.08 | 86.52±11.19 | <0.0001* |

| MAP Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | 80.32±8.36 | 106.20±13.27 | <0.0001* |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 47.11±18.27 | 40.47±12.68 | 0.0002* |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 96.18±29.46 | 123.53±36.38 | <0.0001* |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 165.5±32.79 | 198.46±36.22 | <0.0001* |

| Triglycerides (md/dl) | 115.52±73.81 | 164.90±111.27 | <0.0001* |

Data are means ±SD.

p value <0.05.

HDL: high density lipoprotein, LDL=low density lipoprotein.

Gene Characterization and SNP association with HOMA-IR

Seventeen SNPs were genotyped (Table 2). Three SNPs were removed prior to the start of analyses due to monomorphism in the population (rs11568045, rs11568026) and a MAF less than 0.1 (rs11122576), resulting in 14 SNPs. Five of the SNPs were in linkage disequilibrium (LD) (R2>0.80) with other SNPs (Figure 1). Nine SNPs were significantly (p=0.0001-0.03) associated with lower HOMA-IR and therefore, insulin sensitivity (Table 2).

Association of rs2493134 with HOMA-IR, Fasting Insulin, Fasting Glucose Levels

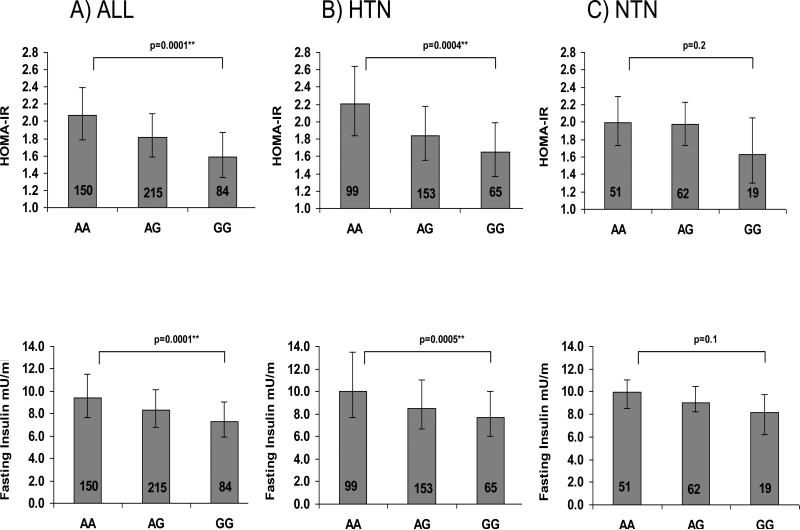

We used rs2493134 for further analyses, because it is the most significant SNP, was genotyped in the entire population, and is in complete LD with p.M268T [M235T] and the promoter variant -44G>A [-6G>A] [21]. Figure 2 demonstrates an association of rs2493134 with HOMA-IR (AA=2.07 (1.79-2.39) AG=1.82(1.58-2.09) GG =1.59 (1.35-1.87), p=0.0001 and fasting insulin levels (AA=9.40 (7.66-11.53) mU/ml AG=8.29 (6.79-10.12) mU/ml GG= 7.29 (5.88-9.04) mU/ml p=0.0001) accounting for age, gender, BMI, study site, and hypertension status in the entire population. No significant association was seen between rs2943134 and fasting glucose levels (p=0.3) or two-hour glucose levels after an oral glucose tolerance test (p=0.5). This initial analysis demonstrated that hypertension status, BMI, and gender were significantly contributing to the variance of HOMA-IR (0.005, <0.0001, <0.0001 respectively).

Figure 2. Association of rs2493134 with Primary and Secondary Phenotypes.

HOMA-IR and fasting plasma insulin values by SNP rs2493134 in entire population A) (All), individuals with hypertension only B) (HTN), and individuals without hypertension C) (NTN). Point estimates (least-square means), error bars (95% CI), and p values were obtained from the mixed model regression accounting for age, gender, BMI, sibling relatedness, and study site.

Because of the effects of hypertension status on the association, we dichotomized the population by hypertension status and examined the association between rs2493134 and insulin phenotypes (HOMA-IR and fasting insulin) (Figure 2). A significant association between rs2493134 and HOMA-IR (AA=2.2 (1.84-2.64) AG=1.84 (1.55-2.18) GG= 1.65 (1.36-1.99) p=0.0004) and fasting insulin (AA=9.97 (7.69-13.46) mU/ml AG=8.50 (6.69-11.02) mU/ml GG= 7.69 (6.05-9.97) mU/ml p=0.0005) existed in the hypertensive population. These results remained significant after accounting for the triglyceride to high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol ratio (p=0.001 HOMA-IR and p=0.002 fasting insulin); a marker of insulin resistance [22]. The normotensive population demonstrated a similar trend, but non-significant association between rs2493134 and HOMA-IR (AA=1.99 (1.73-2.29) AG=1.97 (1.73-2.23) GG= 1.63 (1.30-2.05) p=0.2) and fasting insulin (AA=9.97 (8.5-11.02) mU/ml AG=9.03 (8.25-10.45) mU/ml GG= 8.17 (6.23-9.78) mU/ml p=0.1). Due to the strong influence of hypertension status on the findings, all subsequent exploratory analyses were done with hypertensives only.

Exploratory Analysis: Covariates Known to Influence AGT genotype: Gender and BMI

Since both gender [23] and obesity [2] are known to interact with SNPs of the AGT gene, we investigated the influence of these covariates on the association between rs2493134 and HOMA-IR. Although the multivariate analysis demonstrated that a significant portion of the variance of HOMA-IR was accounted for by gender with men having higher HOMA-IR values (p=0.00001), the interaction between SNP rs2493134 and gender was not significant (p=0.9) indicating that the SNP's association with HOMA-IR was not influenced by gender.

In contrast, our analysis of the effects of BMI on the association of rs2493134 and HOMA-IR suggested that BMI may be moderating the results. An interaction between BMI as a continuous variable and SNP was not significant (p=0.6). However, when the population was stratified by obesity status (Normal: BMI<25kg/m2, Overweight: BMI 25-29kg/m2, Obese: BMI≥30kg/m2) [24], an interaction was close to significant between the obese group and rs2493134 (p=0.15 additive SNP model; p=0.06 dominant SNP model). Further, SNP rs2493134 exhibited a greater beta estimate (beta=-0.20 p=0.007) for the regression model tested in the obese group compared to the beta estimates for the same SNP tested in normal and overweight individuals (beta=- 0.19 p=0.06, beta=-.10 p=0.06) (Table 3).

Table 3.

SNP and HOMA-IR associations in Hypertensive Population Stratified by Obesity Status.

| Normal BMI<25 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs2493134 | N | HOMA-IR estimates | LCI | UCI | Beta | p value |

| AA | 23 | 1.67 | 1.14 | 2.46 | -0.19 | 0.06 |

| AG | 35 | 1.38 | 0.96 | 1.97 | ||

| GG | 12 | 1.15 | 0.73 | 1.67 | ||

| Overweight BMI 25-29 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs2493134 | N | HOMA-IR estimates | LCI | UCI | Beta | p value |

| AA | 41 | 2.01 | 1.70 | 2.36 | -0.10 | 0.06 |

| AG | 74 | 1.73 | 1.51 | 2.01 | ||

| GG | 29 | 1.68 | 1.39 | 2.05 | ||

| Obese BMI>=30 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs2493134 | N | HOMA-IR estimates | LCI | UCI | Beta | p value |

| AA | 35 | 2.89 | 2.41 | 3.46 | -0.20 | 0.007* |

| AG | 44 | 2.25 | 1.92 | 2.64 | ||

| GG | 24 | 1.95 | 1.55 | 2.44 | ||

LCI: lower confidence interval; UCI: upper confidence interval; BMI: body mass index. Point estimates, 95% CI, beta and p values were obtained from a mixed model regression accounting for age, gender, sibling relatedness, and study site.

p value<0.05.

Haplotype Analysis

The SNP LD plot from our hypertensive population indicated that three haplotype blocks existed. Table 4 displays all three haplotype blocks and each block's association with HOMA-IR. Haplotype rs2493137A|rs5050A| rs3789678G|rs2493134A in block 1 and haplotype rs2004776G|rs11122576A|rs699T|rs6687360G in block 2 are significantly associated with HOMA-IR (p=0.0009, beta=0.1965; p=0.02, beta=0.1164). The association of haplotype block 1 with HOMA-IR is significant only when individuals carry the major allele (A) for SNP rs2493134 (p=0.0009 unadjusted; p=0.002 adjusted for age, gender, and BMI). This is similar for rs699 in block 2. The block 2 haplotype is significant only for individuals carrying the major allele (T) (p=0.02 unadjusted; p=0.03 adjusted for age, gender, and BMI).

Table 4. Haplotype Analyses for Association with HOMA-IR in Individuals with Hypertension.

The primary SNP and allele driving the significant findings are bolded.

| BLOCK 1 | HAPLOTYPE | BETA | P VALUE | FREQUENCY |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCGG | -0.1477 | 0.09 | 0.17 | |

| CAGG | -0.1268 | 0.14 | 0.15 | |

| AAAG | -0.1484 | 0.11 | 0.14 | |

| AAGA | 0.1965 | 0.0009 ** | 0.54 | |

| rs2493137|rs5050|rs3789678|rs2493134 | ||||

| BLOCK 2 | HAPLOTYPE | BETA | P VALUE | FREQUENCY |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGCA | -0.0869 | 0.31 | 0.09 | |

| AACA | -0.0968 | 0.16 | 0.18 | |

| GACA | -0.03961 | 0.63 | 0.11 | |

| GACG | -0.07393 | 0.47 | 0.07 | |

| GATG | 0.1164 | 0.02 * | 0.53 | |

| rs2004776|rs11122576|rs699|rs6687360 | ||||

| BLOCK 3 | HAPLOTYPE | BETA | P VALUE | FREQUENCY |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGA | 0.02 | 0.64 | 0.32 | |

| AAC | -0.07 | 0.35 | 0.14 | |

| AGC | -0.11 | 0.21 | 0.09 | |

| CGC | 0.04 | 0.40 | 0.45 | |

| rs3789671|rs3789670|rs7079 | ||||

p value <0.05

p value <0.004.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates a significant association between SNPs of the AGT gene and insulin sensitivity in a Caucasian population. This relationship is robust as evident by the numerous significant associations even after multiple comparison adjustment. The current study also demonstrates an association of AGT haplotypes, specifically rs2493137A|rs5050A|rs3789678G|rs2493134A and rs2004776G|rs11122576A|rs699T|rs6687360G, with HOMA-IR. These haplotypes are driven by the major allele of two SNPs in LD: rs2493134 and rs699. These novel SNP associations implicate variations in the AGT gene with increased insulin sensitivity.

The AGT gene, specifically the p.M268T [M235T] polymorphism, was previously associated with essential hypertension, adrenal and renal response to Ang II, and angiotensinogen levels [1-3] however; an association with this gene and glucose metabolism has been unclear. Sheu et al [9] found no association with p.M268T [M235T] and insulin sensitivity however; both Guo et al. [8] and Takukara et al. [10] demonstrated that p.M268T [M235T] was associated with increased insulin resistance. Our results suggest otherwise however, extensive differences between the study designs and populations may explain the contradictory results and are important to highlight for further investigation. First, each study was conducted in a different ethnicity suggesting that the association of the AGT gene and insulin sensitivity may be ethnically dependent. Further, our analysis accounted for age, gender, BMI, and hypertension status and controlled for medication, diet, and activity while other studies accounted for none or few of these variables. Differences in outcomes between studies suggest that one or all of these variables may be influencing the association observed. Our findings clarify the role of the AGT gene with insulin sensitivity in a Caucasian population by capturing the entire AGT gene, as characterized by HAPMAP, in a well-designed study.

Molecular genetics and physiology studies provide insight into a possible mechanism underlying our finding of an association of the AGT gene with insulin sensitivity. First, molecular genetic studies demonstrate a relationship between variants of the AGT gene, AGT gene expression, and plasma AGT levels. An AGT promoter variant rs5051 (c.-44G>A [-6G>A]), a SNP in complete LD with rs699 and rs2493134, has been shown to increase AGT gene expression in vitro [25, 26]. Subsequent studies demonstrated that increased AGT gene expression lead to increased plasma AGT levels in a mouse model [27]. More recently, AGT gene variants were found to be associated with increased plasma AGT levels in humans [1]. Together, these studies support the hypothesis that variations in the AGT gene lead to increased AGT expression and subsequent increased plasma AGT levels in humans [21]. Important to our study is the following question: How may increases in AGT levels contribute to processes of insulin sensitivity in humans? Human studies of RAAS physiology provide insight into possible answers to this question.

Physiology studies demonstrate a relationship between components of the RAAS and glucose metabolism; potentially linking AGT levels with insulin sensitivity. Infusion of AngII in humans has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity in normotensive individuals with and without type 2 diabetes [28-31]. Sub-pressor doses of AngII exhibit a similar effect without an increase in blood pressure, demonstrating that hemodynamic alterations are not the sole mechanism for improved insulin sensitivity [28]. Studies in animal and cell culture further these findings with AngII (2ug/100g body weight) increasing insulin stimulated glucose uptake in rat adipocytes [32]. In the above in vivo studies, additional AngII was administered exogenously. The same relationships may not exist when the activity of the RAAS is modified physiologically. For example, a recent study demonstrated that consumption of a low salt diet, a state that physiologically increases RAAS activity, resulted in higher HOMA-IR levels [33], supporting the hypothesis that AngII levels per se may not necessarily produce a consistent metabolic effect. The type of effect may be dependent more on the physiologic “appropriateness” of the AngII level. Thus, it is possible that increased plasma AGT levels, a known effect of AGT gene variants, increases AngII levels physiologically inappropriately and thereby affects glucose homeostasis via the mechanisms outlined above.

Our results suggest an influence of obesity, albeit not significant on the study results. An interaction between the AGT gene and BMI has been shown in previous studies [2] and it is possible that with a larger sample size the interaction suggested in our analyses would become significant. AGT gene expression has been shown to be increased on both a high fat diet in human visceral adipocytes [34] and in a hyperinsulinemic state in human 3T3-L1 adipocytes [35]. Further, in humans, plasma ANGII levels have been shown to positively correlate with body weight [36]. Further analyses in larger cohorts are necessary to confirm possible interactions between the AGT gene and BMI on IR. Our data suggest that with obesity, the effect of the p.M268T [M235T] AGT gene variant on insulin sensitivity is enhanced.

The results of our haplotype analysis are consistent with the single SNP analyses; similar to other AGT haplotype studies [37]. The association is primarily driven by rs2493134 and rs699 in haplotype block 1 and block 2. The results demonstrate that major allele carriers are most likely to have elevated HOMA-IR values and are insulin resistant or as described in our SNP results, the minor allele is associated with insulin sensitivity. Interestingly, an extensive haplotype that includes AGT p.M268T [M235T] has been found to be more strongly associated with AGT levels than the SNP alone [1]. This may explain why some individuals known to have an increased frequency of the minor allele of this SNP, African Americans, have an increased risk of IR when our data suggest that the SNP should be protective from altered glucose metabolism. Further studies are necessary to assess the association of the AGT gene with insulin sensitivity in an African American population, specifically; whether extensive haplotype analyses provide the most relevant information.

There are several limitations to this study. First, this gene association study has a relatively small sample size when compared to the “classical” genome wide association approach. However, our study was conducted in a well-phenotyped population where medication, diet, and activity were tightly controlled within an in-patient setting. Our results suggest that studying individuals within a carefully controlled setting enables the use of smaller sample sizes to identify genotype/phenotype associations. Functional data are not present in this study however; previous studies, including one from the HyperPATH cohort, demonstrate that AGT p.M268T [M235T] is associated with increased AGT levels and functional differences in aldosterone secretion, renal blood flow, salt handling and salt sensitivity of blood pressure[1-3, 8,37]. However, even though this SNP is located in AGT's coding region, no direct functional differences have been reported based on genetic variation at this site. Furthermore, even though this SNP is in nearly complete linkage disequilibrium with -6 in the upstream regulatory region, no interactions or effects of other molecular genetic factors, e.g., micro RNAs, variation in methylation function either in the histone or DNA, have been reported. However, intriguingly a recent report raises the possibility that the results of this study may not be related through an effect of AngII, but rather an effect of AGT interacting with its receptor (AGTR1). MicroRNA encoded by intronic SNPs in the AGTR1 has been shown to increase AGTR1 gene expression [38]. It is possible that intronic SNPs of the AGT gene could act in a similar manner, through microRNA, to affect AGT gene expression. No data are available presently to assess this possibility.

In conclusion, this study identifies that SNPs of the AGT gene are associated with insulin sensitivity in Caucasians. Haplotype analysis extends this finding and implicates SNPs rs2493134, and rs699, variants known to affect plasma AGT levels, as the most influential SNPs. Our results indicate that both hypertension status and BMI may be influencing the association with the genotype effect being the strongest in hypertensive, obese individuals. These results demonstrate a potential role for the AGT gene to explain why some individuals, even with an abnormal cardio-metabolic profile, are insulin sensitive. As clinician's attempt to use AGT genotype as a genomic marker for individualized hypertension treatment, the effects of this gene on glucose metabolism should be considered.

Acknowledgements

The project described was supported in part by the following grants: U54LM008748 from the National Library of Medicine, UL1RR025758, Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center, from the National Center for Research Resources and M01-RR02635, Brigham & Women's Hospital, General Clinical Research Center, from the National Center for Research Resources. As well as NIH grants HL47651, HL59424, F31 NR011108 (PCU), K23 HL084236 (JSW), Specialized Center of Research (SCOR) in Molecular Genetics of Hypertension P50HL055000

We thank all other investigators and staff of the HyperPath Protocol including Nancy Brown Vanderbilt University, Nashville TN, as well as the General Clinical Research Center staff, and participants of all protocol sites.

List of Abbreviations

- AGT

Angiotensinogen

- SNP

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism

- HTN

Hypertensive

- NTN

Normotensive

- RAAS

renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

- AngI

angiotensin I

- AngII

angiotensin II

- IR

insulin resistance

- OGTT

oral glucose tolerance test

- MAF

minor allele frequency

- LDL

low density lipoprotein

- HDL

high density lipoprotein

- HWE

Hardy-Weinberg expectations

- BMI

body mass index

- LD

linkage disequilibrium

Appendix

List of Principle Investigators of Each Study Site:

Boston: Gordon H. Williams

Salt Lake City: Paul N. Hopkins

Paris: Xavier Jeunemaitre

Vanderbilt: Nancy Brown

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Disclosures: The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Author contribution: P.C.U. wrote manuscript, study design and conduct, data collection and analysis, data interpretation. B.S. data collection and analysis. J.S.W. study design and conduct, data collection and analysis, data interpretation. L.P. data collection and analysis. B.R. study design and conduct, data interpretation. J.L-S. data interpretation. S.H. data interpretation, P.N.H. study design and conduct, data collection and analysis. X.J. study design and conduct, data collection and analysis. G.K.A. data interpretation G.H.W. study design and conduct, data collection and analysis, data interpretation.

References

- 1.Watkins WS, Hunt SC, Williams GH, et al. Genotype-phenotype analysis of angiotensinogen polymorphisms and essential hypertension: The importance of haplotypes. J Hypertens. 2010;28(1):65–75. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328332031a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hopkins PN, Lifton RP, Hollenberg NK, et al. Blunted renal vascular response to angiotensin II is associated with a common variant of the angiotensinogen gene and obesity. J Hypertens. 1996;14(2):199–207. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199602000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hopkins PN, Hunt SC, Jeunemaitre X, et al. Angiotensinogen genotype affects renal and adrenal responses to angiotensin II in essential hypertension. Circulation. 2002;105(16):1921–1927. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000014684.75359.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abuissa H, Jones PG, Marso SP, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers for prevention of type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(5):821–826. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The NAVIGATOR Study Group Effect of valsartan on the incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(16):1477–1490. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DREAM Trial Investigators Effect of ramipril on the incidence of diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1551–1562. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonnet F, Patel S, Laville M, et al. Influence of the ACE gene insertion/deletion polymorphism on insulin sensitivity and impaired glucose tolerance in healthy subjects. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(4):789–794. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo X, Cheng S, Taylor KD, et al. Hypertension genes are genetic markers for insulin sensitivity and resistance. Hypertension. 2005;45(4):799–803. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000154786.17416.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheu WH, Lee WJ, Jeng CY, et al. Angiotensinogen gene polymorphism is associated with insulin resistance in nondiabetic men with or without coronary heart disease. Am Heart J. 1998;136(1):125–131. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(98)70192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takakura Y, Yoshida T, Yoshioka K, et al. Angiotensinogen gene polymorphism (Met235Thr) influences visceral obesity and insulin resistance in obese japanese women. Metabolism. 2006;55(6):819–824. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raji A, Williams GH, Jeunemaitre X, et al. Insulin resistance in hypertensives: Effect of salt sensitivity, renin status and sodium intake. J Hypertens. 2001;19(1):99–105. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200101000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chamarthi B, Kolatkar NS, Hunt SC, et al. Urinary free cortisol: An intermediate phenotype and a potential genetic marker for a salt-resistant subset of essential hypertension. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(4):1340–1346. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams JS, Williams GH, Jeunemaitre X, et al. Influence of dietary sodium on the reninangiotensin-aldosterone system and prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy by EKG criteria. J Hum Hypertens. 2005;19:133–138. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donovan DS, Soloman CG, Seely EW, et al. Effect of sodium intake on salt sensitivity. Am J Physiol. 1993;264(5):730–734. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1993.264.5.E730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, et al. Homeostasis model assessment: Insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28(7):412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.International HAPMAP Consortium: The International HAPMAP Project. Nature. 2003;426:789–796. doi: 10.1038/nature02168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.den Dunnen JT, Antonarakis SE. Mutation nomenclature extensions and suggestions to describe complex mutations: A discussion. Hum Mutat. 2000;15:7–12. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(200001)15:1<7::AID-HUMU4>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halangk J, Berg T, Neumann K, et al. Evaluation of angiotensinogen c. 1-44G>A and p.M268T variants as risk factors for fibrosis progression in chronic hepatitis C and liver disease of various etiologies. Gen Test and Mol Bioma. 2009;13(3):407–414. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2008.0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Diabetes Association Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(S1):S62–S69. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lalouel JM, Rohrwasser A, Terreros D, et al. Angiotensinogen in essential hypertension: From genetics to nephrology. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:606–615. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V123606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLauglin T, Abbasi F, Cheal K, et al. Use of metabolic markers to identify overweight individuals who are insulin resistant. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:802–809. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai CT, Hwang JJ, Lai LP, et al. Interaction of gender, hypertension, and the angiotensinogen gene haplotypes on the risk of coronary artery disease in a large angiographic cohort. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203(1):249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults--the evidence report. national institutes of health. Obes Res. 1998;6(Suppl 2):51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inoue I, Nakajima J, Williams CS, et al. A nucleotide substitution in the promoter of human angiotensinogen is associated with essential hypertension and affects basal transcription in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1786–1797. doi: 10.1172/JCI119343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeunemaitre X, Soubrier F, Kotelevtsev YV, et al. Molecular basis of human hypertension: Role of angiotensinogen. Cell. 1992;71:169–180. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90275-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim HS, Krege J, Kluckman KD, et al. Genetic control of blood pressure and angiotensinogen locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:2735–2739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fliser D, Arnold U, Kohl B, et al. Angiotensin II enhances insulin sensitivity in healthy volunteers under euglycemic conditions. J Hypertens. 1993;11(9):983–988. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199309000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morris AD, Petrie JR, Ueda S, et al. Pressor and subpressor doses of angiotensin II increase insulin sensitivity in NIDDM. dissociation of metabolic and blood pressure effects. Diabetes. 1994;43(12):1445–1449. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.12.1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jonk AM, Houben AJ, Schaper NC, et al. Angiotensin II enhances insulin-stimulated whole-body glucose disposal but impairs insulin-induced capillary recruitment in healthy volunteers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(8):3901–3908. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buchanan TA, Thawani H, Kades W, et al. Angiotensin II increases glucose utilization during acute hyperinsulinemia via a hemodynamic mechanism. J Clin Invest. 1993;92(2):720–726. doi: 10.1172/JCI116642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Juan CC, Chien Y, Wu LY, et al. Angiotensin II enhances insulin sensitivity in vitro and in vivo. Endocrinology. 2005;146(5):2246–2254. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garg R, Williams GH, Hurwitz S, et al. Low-salt diet increases insulin resistance in healthy subjects. Metabolism. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.09.005. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rahmouni K, Mark AL, Haynes WG, et al. Adipose depot-specific modulation of angiotensinogen gene expression in diet-induced obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;286(6):E891–5. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00551.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones BH, Standridge MK, Taylor JW. Angiotensinogen gene expression in adipose tissue: Analysis of obese models and hormonal and nutritional control. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(1 Pt 2):R236–42. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.1.R236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saiki A, Ohira M, Endo K, et al. Circulating angiotensin II is associated with body fat accumulation and insulin resistance in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2009;58:708–713. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jeunemaitre X, Inoue I, Williams CS, et al. Haplotypes of angiotensinogen in essential hypertension. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:1448–1460. doi: 10.1086/515452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sethupathy P, Borel C, Gagnebin M, et al. Human microRNA-155 on chromosome 21 differentially interacts with its polymorphic target in the AGTR1 3′ untranslated regions: a mechanism for functional single-nucleotide polymorphisms related to phenotypes. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:405–413. doi: 10.1086/519979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]