Abstract

Rational and Objectives

During radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA) for atrial fibrillation, the esophagus is at risk for thermal injury. In this study we compared using C-arm CT to clinical CT, without administration of oral contrast, to visualize the esophagus and its relationship to the left atrium (LA) and the ostia of the pulmonary veins (PV) during the RF ablation procedure.

Materials and Methods

Sixteen subjects underwent both cardiac clinical CT and C-arm CT. CT scans were obtained on a multi-detector CT using a standard ECG-gated protocol. C-arm CT scans were obtained using either a multi-sweep protocol with retrospective ECG-gating or a non-gated single-sweep protocol. C-arm CT and CT scans were analyzed in a random order and then compared for the following criteria: a) visualization of the esophagus (yes/no), b) relationship of esophagus position to the 4 PVs, and c) direct contact or absence of a fat pad between the esophagus and PV antrum.

Results

a) The esophagus was identified in all C-arm CT and CT scans. In 4 cases, orthogonal planes were needed on C-arm CT (inferior PV level); b) In 6 patients, the esophagus location on C-arm CT was different from CT; c) Direct contact was reported in 19/64 (30%) of the segments examined on CT vs. 26/64 (41%) on C-arm CT. In 5/64 segments (8%), C-arm CT overestimated a direct contact of the esophagus to the LA.

Conclusion

C-arm CT image quality without administration of oral contrast agents was shown to be sufficient for visualization of the esophagus location during an RFCA procedure for atrial fibrillation.

Keywords: Atrial Fibrillation, Esophageal Fistula, Ablation, C-Arm CT, Computerized Tomography

Introduction

Radiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA) of atrial fibrillation has emerged as an important therapeutic option for patients refractory to anti-arrhythmic medications. While there are many approaches to ablation of atrial fibrillation, isolation of the pulmonary veins (PV) remains crucial for success of this procedure (1). As the PVs are posterior structures, successful isolation requires ablation in the posterior left atrium (LA). In addition, RFCA may often be extended to other areas of the LA, in particular, the posterior wall, the mitral isthmus, the atrial roof (2–4), and the inter-atrial septum(5).

Because of its proximity to the posterior wall of the LA, the esophagus may be at risk for thermal injury during RFCA (6, 7). Atrio-esophageal fistula has been reported (6, 8, 9) in the literature as a rare event(10), but one with a significantly high mortality rate.

Pre-procedural imaging using computed tomography (CT) (11) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has commonly been used pre-ablation as there can be significant anatomical variation of the PV and LA anatomy between patients. Current electroanatomical mapping programs also allow registration of the electroanatomical map with the three-dimensional (3D) image obtained previously. Using these 3D images, the esophagus can also be visualized and its location noted along the posterior wall of the LA (12).

One potential disadvantage of using the 3D images from pre-procedural CT or MRI is that the image is often obtained days or weeks prior to the procedure. As the esophagus has been shown to move on occasion during ablation procedures (13, 14), reliance on the 3D reconstruction of the esophagus may be misleading as it may not accurately depict the relationship between the esophagus, the posterior wall of the LA, and the ostia of the PVs.

Three-dimensional images can be obtained at the time of the procedure using a ceiling-mounted C-arm system with the ability to acquire images during rotation of the C-arm (Rotational Fluoroscopic Acquisition Imaging or C-Arm CT). This rotation can be gated to the ECG and has been shown to be accurate (compared with clinical gated CT) in both animals (15) and humans (16). The C-arm CT scan adds approximately 10 minutes to the RF procedure and the images obtained can be reconstructed and rendered for visualization within 3 minutes.

The subjects enrolled in this study were originally prospectively enrolled to compare the image quality of cardiac C-arm CT and clinical cardiac CT (reference standard). In the current study, in an attempt to evaluate future potential in imaging guidance of cardiac RF ablation, we retrospectively review the images of the same 16 subjects to evaluate whether the 3D reconstructed images obtained using a C-arm CT provide adequate image quality for visualization of the esophagus and its relationship to the LA and the ostia of the PVs. A 64-slice multi-detector clinical cardiac CT of the same subjects was used as reference standard. The secondary goal of this retrospective study was to assess the temporal changes in the relationship between esophagus and LA between the time of the clinical CT and of the C-arm CT.

Methods

Patients

From June 2006 to May 2008, 16 patients with a history of atrial fibrillation were enrolled in this study. All 16 patients agreed to have a C-arm CT in addition to the clinical CT scan. Creatinine levels were tested to ensure renal sufficiency and no patients had a history of allergic reaction to iodinated contrast. All 16 subjects consecutively underwent clinical CT scanning and C-arm CT of the heart. Of the 16 subjects, 8 were candidates for RFCA of the LA and the other 8 were previously treated with RFCA for atrial fibrillation and agreed to undergo a C-arm CT scan. Informed consent was obtained and the imaging protocols were approved by the institutional investigational review board. Clinical CT scans and C-arm CT images of all sixteen subjects were retrospectively reviewed.

Imaging Protocols

Cardiac CT scan

An ECG-gated, multi-detector CT (SOMATOM Sensation 64, Siemens AG, Healthcare Sector, Forchheim Germany, referred to as clinical CT) was obtained in all 16 patients. Initially a scout scan from the neck to diaphragm was obtained, and then a monitoring scan at approximatively 4 cm below the carina was performed (120 Kv, 20 Eff mAs). Scanning time for the LA acquisition was obtained using an automated bolus timing software (Care Bolus, Siemens AG, Healthcare Sector), which uses a region of interest (ROI) positioned in the LA to begin scanning when the contrast enhancement level corresponds to 150 HU.

Images were acquired during a single breath hold of approximately 20 seconds (scan time ≤ 25 sec) following an intravenous injection with a duration equal to scan time + 5 seconds of iodinated contrast (Omnipaque 300, GE Healthcare) The injection rate ranged from 3.5 to 5.5 mL/s depending on the patient body weight. The total volume of contrast varied accordingly. Acquisition parameters were 64×0.6 mm collimation at 330 ms rotation time, 120 kV, 800 mAs, and 0.2 pitch, with a FOV of 500 mm. Using the dose-length product, as reported on the system, and the conversion factor 0.017 mSv/(mGy*cm) for chest CT (17), the dose was 16 mSv ± 5 mSv. Two sets of images were then reconstructed at 30% and 0–90% (10 reconstructed volumetric datasets) of the ECG- triggered acquired images with a slice thickness of 1 mm and reconstruction diameter ranging from 160 to 280 mm depending on the body habitus.

Cardiac C-arm CT Scan

ECG-gated protocol (13 subjects)

A Siemens AXIOM Artis dTA C-arm system (Siemens AG, Healthcare Sector) was modified to allow acquisition of four bidirectional sweeps during synchronized acquisition of the ECG for retrospective gating. In subjects who underwent the scan prior to ablation, 100 – 150 mL (injection rate: 4–15 mL/s) of intravenous contrast (Omnipaque 300 or Visipaque 320) was given via a pigtail catheter placed in the inferior vena cava just below the level of the diaphragm.

In the subjects who underwent the scan after RFCA, a total of 50–70 mL of iodinated contrast (Visipaque 320, injection rate 3–4 mL/s) was administered via bilateral peripheral intravenous injection. Images were acquired at a fixed delay of 15 seconds and during a breath hold of approximately 25 to 30 seconds. During each 4-second sweep, 190 projection images were obtained, for a total of 760 images (detector resolution 616 × 480 pixels, 60 frames/s), at 90–125 kVp, for a total of 1030 mAs ± 280 mAs (referenced to 125 kVp for purposes of comparison (18)). Given the measured mAs from the scans and using a conversion factor of 0.01 mSv/mAs as calculated from Monte Carlo simulations (19), the dose is approximately 11 mSv ± 3 mSv.

Retrospectively gated C-arm CT image volumes were reconstructed in all subjects using a 3D Feldkamp algorithm modified to account for irregular but stable scan trajectories with additional correction algorithms for scatter, beam hardening, truncation, and ring artifact (Syngo DynaCT, Siemens AG, Healthcare Sector). Technical details of the imaging, image processing, and reconstruction protocol for cardiac C-Arm CT scanning have been previously published (20).

Non-gated protocol (3 subjects)

A pigtail catheter was positioned in the main pulmonary artery and a total of 89 mL of iodinated contrast was injected. First, a 20 mL bolus of contrast was injected at 5 mL/s through the pigtail catheter and scanning was initiated when the iodinated contrast was visualized in the LA. Then, a single, 5s rotational scan was acquired during the injection of the remaining 69 mL (injection rate: 15 mL/s) and images were obtained without ECG-gating. A total of 235 projection images were obtained (detector resolution 616 × 480 pixels, 60 frames/s) at 125 kVp for a total of 380 mAs ± 140 mAs, with a corresponding dose of approximately 4 mSv ± 1.5 mSv.

Image analysis

The clinical CT scan and C-arm CT images of each patient were transferred to a Multi-Modality Workstation (Syngo-X Workplace, 3D- Volume Task-card, Siemens AG, Healthcare Sector) for image analysis. The C-arm CT images were first evaluated, followed by evaluation of the clinical CT images, with clinical CT blinded to the results of the C-arm CT evaluation, in order to ensure an unbiased interpretation of the C-arm CT scans. C-arm CT and clinical CT findings of each patient were then compared at a later time. The average time elapsed between the CT scan and the C-arm CT scan was 98 days (range: 1–219).

For each scan, the following parameters were evaluated:

Esophagus visualization (yes/no)

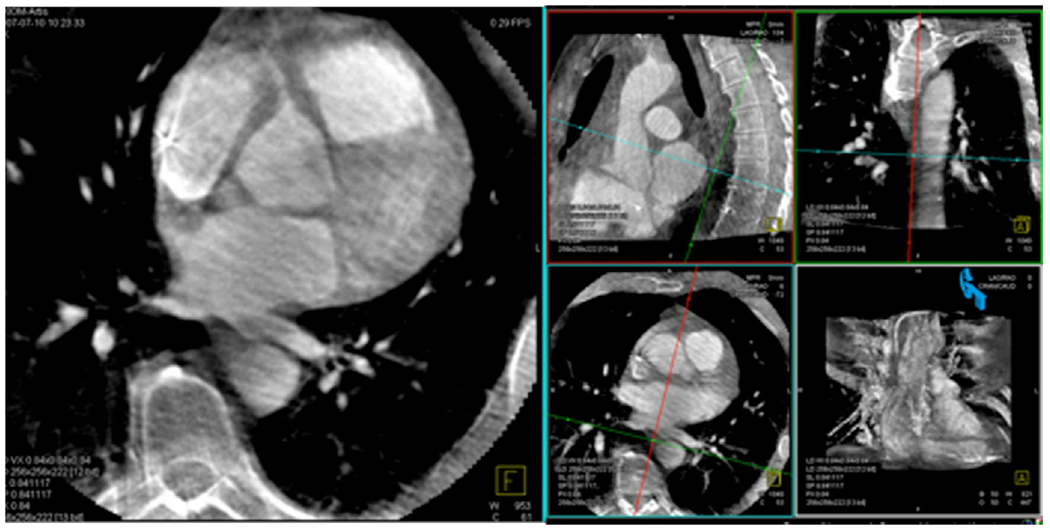

Images in multiple planes were used to accurately identify the esophagus (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Visualization of the esophagus.

On this C-arm CT reconstructed image of the heart, the cross-lines are centered on the esophagus on the 3 spatial planes (axial, sagittal and coronal). The availability of 3D planes helped confirm the findings on the axial plane.

Localization and proximity to a PV antrum

Each pulmonary antrum was identified on the axial plane and this scan level, defined as the PV antrum plane, resulted in 4 planes (corresponding to the four main PVs) per study and a total of 64 ostia examined. On each of the four axial planes selected, the esophagus was identified and its position was assigned to an area in the LA using the anatomic map previously used by Cummings et al. (12) and as illustrated in Fig. 2 a–c. This anatomic map divides the LA into 6 predefined areas as follow: (1) right superior PV antrum, (2) right inferior PV antrum, (3) superior-posterior LA wall, (4) inferior-posterior LA wall, (5) left superior PV antrum, and (6) left inferior PV antrum.

Fig. 2. a–c: Example of assignment of the esophagus location to a predefined left atrium area.

These 3 axial CT images of the left atrium show the ostia of the LSPV (fig. 2a), RSPV (fig. 2b), LIPV and RIPV (fig.2c). In this particular case, the esophagus location corresponded to area 5 at the axial level of the LSPV, to area 3 at the level of the RSPV, and to area 4 at the inferior PV level. The structures delineated by a triangle represent the presence of a fat pad.

Esophagus movement

Changes in esophagus position with respect to the pre-assigned areas of the LA between the CT scan and C-arm CT scan were identified.

Absence of fat pad (direct contact between esophagus and LA/ PV ostia)

Direct contact between the esophagus and the antra of the PVs was defined as the non-visualization of a defined bundle of fat tissue separating the esophagus.

Results

A total of sixteen patients, 11 males and 5 females with a mean age of 63 years (range: 44–75) underwent clinical CT and C-arm CT imaging.

Visualization of the esophagus

The esophagus was visualized in all 16 patients using both C-arm CT as well as the clinical CT. From our limited sample size, ECG-gating compared to non-ECG gating had no effect on the visualization of the esophagus (Fig. 3 a,b). The esophagus could be visualized posterior to the superior veins using the axial plane alone, however, orthogonal planes were needed to visualize the esophagus posterior to the inferior veins in 4 patients (25%) as the esophagus is more commonly compressed in the position posterior to the inferior veins.

Fig. 3. a, b: ECG-gated and non-gated C-arm CT scans.

For the purpose of esophagus visualization, C-arm CT ECG-gated (fig. 3a) and non-gated (fig. 3b) images did not show significant differences, as shown in these two different patients.

Relationship of esophagus and LA (Table 1 and Fig. 2 a–c)

Table 1. Esophagus location.

The numbers in the boxes correspond to the anatomical area were the esophagus was located on the axial plane at the level of each of the 4 main PVs. Bold numbers correspond to the cases in which a discrepancy between C-arm CT and clinical CT occurred (14 segments in 6 patients).

| Subject # | RSPV | LSPV | RIPV | LIPV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-arm CT |

CT | C-arm CT |

CT | C-arm CT |

CT | C-arm CT | CT | |

| 1 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 |

| 2 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 4 |

| 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 6 |

| 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 7 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| 8 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 9 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 10 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 11 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 12 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 13 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 14 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 15 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 4 |

| 16 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 6 |

RSPV region (area1)

In 1 (6%) subject and on C-arm CT only the esophagus position was found to be posterior to this region of the LA.

RIPV region (area 2)

In 2 (12%) subjects the esophagus position was found to be posterior to this region on C-arm CT only.

Superior-posterior LA wall (area 3)

The esophagus was found to be posterior to this region of the LA in 4/16 (25%) subjects on clinical CT vs. 3/16 (19%) on C-arm CT.

Inferior-posterior LA wall (area 4)

The esophagus was found to be posterior to this region of the LA in 8/16 (50%) subjects on clinical CT vs. 6/16 (38%) on C-arm CT.

LIPV region (area 5)

In 12/16 (75%) subjects on both clinical CT and C-arm CT the esophagus was found to be posterior to the LSPV region.

RIPV region (area 6)

The esophagus was found to be posterior to this region in 13/16 (81%) subjects on clinical CT vs. 12/16 (75%) subjects on C-arm CT.

Esophagus movement (Fig. 4 a,b)

Fig. 4. a, b: Temporal changes.

Axial CT (fig. 4a) and C-arm CT (fig.4b) images of the same patient show a change in the esophagus position from the clinical CT to the time of the procedure.

In 6 (37%) different subjects (1 non-ECG gated), a change in the relationship between the esophagus and the ostia of the 4 main PVs was observed in 21% (14/64) of the areas examined.

Absence of fat pad (direct contact between esophagus and LA/ PVs ostia)

Out of the 64 PV ostia analyzed for each technique, a direct contact between the esophagus and the LA/PVs was reported in 19/64 (30%) segments examined on clinical CT vs. 26/64 (41%) on C-arm CT, resulting in 7 segments where the C-arm CT scan, but not the CT scan, shows the esophagus in contact with the fat pad. In 2 of these cases, the esophagus moved to a different pre-assigned area of the LA. In the remaining 5 subjects, where the esophagus was located in the same area on both C-arm CT and CT scans, the C-arm CT showed direct contact between the esophagus and the LA while clinical CT showed the presence of a fat pad. Thus C-arm CT underestimated the presence of a fat pad.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report of esophagus visualization on C-arm CT without administration of oral contrast agents. While esophageal imaging can be obtained using other modalities, imaging is usually performed at a different time compared to the procedure, with the intrinsic limitation, due to dynamic esophageal changes, of not accurately depicting the esophagus location at the time of RFCA.

Ablation in the posterior wall of the LA has led to recognition of a rare but very serious complication, that of atrio-esophageal fistula (6, 7). Though atrio-esophageal fistula formation is rare, it is associated with a very high mortality and morbidity rate due to air embolism, sepsis, and endocarditis (21). For this reason, esophageal imaging in patients undergoing RFCA has become an important subject of investigation.

Several imaging techniques have been proposed for esophagus assessment prior to atrial RFCA. Traditionally, CT or MRI have been performed with or without the administration of oral contrast medium for esophageal outline (2, 11, 12, 14, 22). Intra-procedural echocardiography of the esophagus (23) has also been described as a monitoring technique to avoid atrio-esophageal fistulas (24). This technique has the advantage of monitoring the esophagus location in real-time, however, esophageal visualization may be limited by the absence of distension by gas or saliva. Also, visualization of the esophagus by echocardiography requires highly experienced operators.

Three-dimensional C-arm CT imaging of the LA and PVs has recently been described for evaluation of the LA (15, 25, 26). Orlov and Li (25, 27) reported imaging of the LA and esophagus using non-ECG gated C-arm CT (3D rotational angiography). These researchers used barium sulfate to outline the esophagus and examine the relationship with the posterior wall of the LA. However, patients with swallowing dysfunction or affected by airway diseases may have difficulty with this technique. Furthermore, while the administration of oral contrast allows for a better visualization of the esophageal lumen and new software (28) may take advantage of high density properties to create a virtual esophageal route, the passage of liquid through the esophagus may stimulate peristalsis, rendering the assessment of its position even less reliable. In a recent publication, an esophageal reconstruction using C-arm CT after the administration of oral contrast was compared with clinical CT. However, in 58% of the study population, a correlation between clinical CT and C-arm CT was not possible due to insufficient amounts of oral contrast in either one or the other of the imaging techniques(29). Also, the administration of sufficient quantities of oral contrast to trace the esophageal outline may lead to artifacts in C-arm CT images, impairing image quality of LA and PV assessment. A balance between the two imaging goals of esophageal visualization and LA and PV visualization may be difficult to achieve.

In our series, the esophagus was visualized without administering oral contrast agents in all of the patients and the quality of the images was considered satisfactory for the purposes of determining esophagus position and relationship to RFCA targets (Fig. 5 a–d).

Fig. 5. a–d: Examples of visualization of the esophagus.

Axial CT (fig. 5a) and C-arm CT (fig.5b) images of the same patient show excellent visualization of the esophagus, comparable to the corresponding CT image. In a different patient, axial CT (fig. 5c) and C-arm CT (fig.5d) images show how even in images affected by severe artifacts (worst case), the visualization of the esophagus was still possible.

To our knowledge this is the first study examining the temporal changes in the relationship between the position of the esophagus using cross-sectional images. Piorkowski et al. (30) compared the distance between the PVs and center of the esophagus using electroanatomic mapping with the anatomical map obtained from clinical CT. The authors compared the CT measurements of the post RFCA clinical CT with those obtained on the pre-procedure CT scan. No significant change in esophagus position was determined. However, as also acknowledged by the authors, an accurate assessment of very short distances on clinical CT may be limited by the scan resolution and this limitation, in addition to an arbitrary measurement of the distance between PV ostium and esophagus, can influence measurement accuracy.

We believe that our result showing the temporal change of the esophagus position in 6 subjects (37%) highlights the importance of obtaining an intra-procedural anatomic mapping of the esophagus with the advantage in the future of providing the physician with a more accurate and reliable guide for procedural safety. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, an evaluation of the temporal changes of esophagus position during the procedure was not determined, although multiple non-ECG gated scans would be possible.

Recently, novel techniques such as esophageal temperature monitoring(31) and electroanatomic mapping of the LA(28, 30) using different software such as CARTO ™ (Biosense, Webster, Diamond Bar, CA, USA) or NavX ™ (St. Jude Medical, Seattle, WA, USA) have been developed. Esophageal temperature measurement using dedicated probes may warn the operator about an increase in the physiological temperature (31). However, since the thickness of the wall of the esophagus in normal subjects is not usually greater than 3 to 5 mm and the probe is measuring the temperature inside the esophageal lumen, an injury of the wall may eventually occur by the time an increase of the luminal temperature is detected(32).

A map of the LA and the esophagus can be displayed using software for electroanatomical mapping, however, the map obtained is a “virtual” map and is usually fused to a 3D segmented volume of a pre-procedural study, often a CT scan, to allow for improved anatomic correlation. A small number of reports describe assessment of esophagus position using an electroanatomical map. For example, Kennedy et al.(33) compared the position of the esophagus during repeat RFCA procedures as tagged on electroanatomical maps using cinefluoroscopic images of the esophagus during barium swallow. Using the electroanatomical maps from subsequent RFCA procedures, the position of the esophagus was classified as being adjacent to the left- or right-sided PVs or along the middle portion of the posterior LA and the distance between the esophagus and the ostia of the PVs was measured. These investigators found stability in the esophagus position in 83% of their study group. This percentage is higher than our result (63%), however this could be attributed to the different techniques. Sherzer et al. (28) also utilized an electroanatomical mapping system to create a virtual esophageal tube and no changes in esophageal location were observed in 6 patients with repeated procedures.

In regards to the assessment of a fat pad, C-arm CT images seemed to overestimate a direct contact to the posterior wall of the LA (21%). This minor limitation does not affect the procedure safety but in fact influences the physician to adopt a more prudent approach such as the use of decreased ablation power and/or temperature settings (6).

The main limitation of this study is represented by the small number of subjects. Additionally, since a single C-arm CT scan was performed at the beginning of the procedure and the current study consisted of a retrospective analysis of the images obtained, an evaluation of the temporal changes of esophagus position during the procedure was not assessed.

Limitations of the C-arm CT application may include the need for intravenous contrast as well as the use of ionizing radiation. With respect to these two characteristics, C-arm CT is similar to clinical CT, with the advantage that C-arm CT can be performed in the electrophysiology suite(15). For the protocols used in this study, the dose from both non-gated and ECG-gated C-arm CT was less than clinical CT and the ability to acquire 3D volumetric images at the time of the procedure may eventually replace the need for a pre-CT. Also, while the C-arm CT may delineate the esophagus at the time of imaging, movement of the esophagus during the procedure could lead to incorrect localization if image updates are not acquired. The risk associated with esophagus motion could be minimized by ablating the regions closest to the esophagus in close temporal proximity to the acquisition of the 3D C-arm CT images.

Conclusions

Three-dimensional imaging using C-arm CT is a valuable technique with the ability to assess soft tissue structures, such as the esophagus, during the RFCA procedure. The possibility to fuse the volumetric C-arm CT images to an electroanatomical map may provide useful image guidance for RFCA, combining the real-time information of the electroanatomical mapping with an intra-procedure volumetric imaging study. When C-arm CT imaging is obtained for atrial RFCA planning and guidance, identification and accurate localization of the esophagus does not require the administration of oral contrast agents.

Acknowledgments

Grants supporting research: Research sponsored by Siemens Medical Solutions entitled "Cardiac Imaging using C-arm CT" and by the National Institutes of Health entitled "C-Arm CT for Guidance of Cardiac Interventions" R01 HL087917 and R01 HL098683.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Haissaguerre M, Jais P, Shah DC, et al. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(10):659–666. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809033391003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsao HM, Wu MH, Higa S, et al. Anatomic relationship of the esophagus and left atrium: implication for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2005;128(4):2581–2587. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jais P, Haissaguerre M, Shah DC, Chouairi S, Clementy J. Regional disparities of endocardial atrial activation in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1996;19(11 Pt 2):1998–2003. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1996.tb03269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wongcharoen W, Tsao HM, Wu MH, et al. Morphologic characteristics of the left atrial appendage, roof, and septum: implications for the ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17(9):951–956. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiam PT, Ruiz CE. Percutaneous transcatheter left atrial appendage exclusion in atrial fibrillation. J Invasive Cardiol. 2008;20(4):E109–E113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pappone C, Oral H, Santinelli V, et al. Atrio-esophageal fistula as a complication of percutaneous transcatheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2004;109(22):2724–2726. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131866.44650.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scanavacca MI, D'Avila A, Parga J, Sosa E. Left atrial-esophageal fistula following radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2004;15(8):960–962. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2004.04083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kottkamp H, Hindricks G, Autschbach R, et al. Specific linear left atrial lesions in atrial fibrillation: intraoperative radiofrequency ablation using minimally invasive surgical techniques. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(3):475–480. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01993-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sonmez B, Demirsoy E, Yagan N, et al. A fatal complication due to radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation: atrio-esophageal fistula. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76(1):281–283. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cronin P, Sneider MB, Kazerooni EA, et al. MDCT of the left atrium and pulmonary veins in planning radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation: a how-to guide. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183(3):767–778. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.3.1830767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cury RC, Abbara S, Schmidt S, et al. Relationship of the esophagus and aorta to the left atrium and pulmonary veins: implications for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2(12):1317–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cummings JE, Schweikert RA, Saliba WI, et al. Assessment of temperature, proximity, and course of the esophagus during radiofrequency ablation within the left atrium. Circulation. 2005;112(4):459–464. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.509612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Good E, Oral H, Lemola K, et al. Movement of the esophagus during left atrial catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(11):2107–2110. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pollak SJ, Monir G, Chernoby MS, Elenberger CD. Novel imaging techniques of the esophagus enhancing safety of left atrial ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16(3):244–248. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2005.40560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Ahmad A, Wigstrom L, Sandner-Porkristl D, et al. Time-resolved three-dimensional imaging of the left atrium and pulmonary veins in the interventional suite--a comparison between multisweep gated rotational three-dimensional reconstructed fluoroscopy and multislice computed tomography. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5(4):513–519. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehdizadeh AFR, Wang PJ, Zei PC, Hsia HH, Moore T, Rosenberg J. Al-Ahmad A Comparison of Pulmonary Veins and Left Atrial Dimensions in Humans using Gated Rotational Cardiac Fluoroscopy vs. Cardiac CT. JACC. 2008 Abstract book supplement, 1008-98(1008-98). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bongartz G, Golding SJ, Jurik GA, et al. European guidelines on quality criteria for computed tomography. In: Commission E, editor. Commission E ed. Book European guidelines on quality criteria for computed tomography. 1999. City. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Son HK, S.H. L, Nam S, Kim HJ. Radiation dose during CT scan with PET/CT clinical protocols. Book Radiation dose during CT scan with PET/CT clinical protocols. 2006:2210–2214. City. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wielandts JY, Smans K, Ector J, De Buck S, Heidbuchel H, Bosmans H. Effective dose analysis of three-dimensional rotational angiography during catheter ablation procedures. Phys Med Biol. 2010;55(3):563–579. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/3/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lauritsch G, Boese J, Wigstrom L, Kemeth H, Fahrig R. Towards cardiac C-arm computed tomography. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2006;25(7):922–934. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2006.876166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cummings JE, Schweikert RA, Saliba WI, et al. Brief communication: atrial-esophageal fistulas after radiofrequency ablation. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(8):572–574. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-8-200604180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemola K, Sneider M, Desjardins B, et al. Computed tomographic analysis of the anatomy of the left atrium and the esophagus: implications for left atrial catheter ablation. Circulation. 2004;110(24):3655–3660. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000149714.31471.FD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kenigsberg DN, Lee BP, Grizzard JD, Ellenbogen KA, Wood MA. Accuracy of intracardiac echocardiography for assessing the esophageal course along the posterior left atrium: a comparison to magnetic resonance imaging. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18(2):169–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren JF, Lin D, Marchlinski FE, Callans DJ, Patel V. Esophageal imaging and strategies for avoiding injury during left atrial ablation for atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3(10):1156–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orlov MV, Hoffmeister P, Chaudhry GM, et al. Three-dimensional rotational angiography of the left atrium and esophagus--A virtual computed tomography scan in the electrophysiology lab? Heart Rhythm. 2007;4(1):37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thiagalingam A, Manzke R, D'Avila A, et al. Intraprocedural volume imaging of the left atrium and pulmonary veins with rotational X-ray angiography: implications for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19(3):293–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li JH, Haim M, Movassaghi B, et al. Segmentation and registration of three-dimensional rotational angiogram on live fluoroscopy to guide atrial fibrillation ablation: a new online imaging tool. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6(2):231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sherzer AI, Feigenblum DY, Kulkarni S, et al. Continuous nonfluoroscopic localization of the esophagus during radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18(2):157–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nolker Georg GKJ, Harald Marschang, Guido Ritscher, Stefan Asbach, Nassir Marrouche, Johannes Brachmann. Sinha Anil Martin Three-Dimensional Left Atrial and Oesophagus Reconstruction Using Cardiac C-Arm Computed Tomography with Image Integration into Fluoroscopic Views for Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation: Accuracy of a Novel Modality in Comparison to Multislice Computed Tomography. Heart Rhythm. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piorkowski C, Hindricks G, Schreiber D, et al. Electroanatomic reconstruction of the left atrium, pulmonary veins, and esophagus compared with the "true anatomy" on multislice computed tomography in patients undergoing catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3(3):317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Redfearn DP, Trim GM, Skanes AC, et al. Esophageal temperature monitoring during radiofrequency ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16(6):589–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.40825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cummings JE, Barrett CD, Litwak KN, et al. Esophageal luminal temperature measurement underestimates esophageal tissue temperature during radiofrequency ablation within the canine left atrium: comparison between 8 mm tip and open irrigation catheters. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19(6):641–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kennedy R, Good E, Oral H, et al. Temporal stability of the location of the esophagus in patients undergoing a repeat left atrial ablation procedure for atrial fibrillation or flutter. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19(4):351–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.01051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]