Abstract

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) and their associated regulatory networks are increasingly being implicated in mediating a complex repertoire of neurobiological functions. Cognitive and behavioral processes are proving to be no exception. Here, we discuss the emergence of many novel, diverse, and rapidly expanding classes and subclasses of short and long ncRNAs. We briefly review the life cycles and molecular functions of these ncRNAs. We also examine how ncRNA circuitry mediates brain development, plasticity, stress responses, and aging and highlight its potential roles in the pathophysiology of cognitive disorders, including neural developmental and age-associated neurodegenerative diseases as well as those that manifest throughout the lifespan.

Keywords: cognitive disorder, enhancer, learning, long non-coding RNA, memory, microRNA, non-coding RNA, REST/NRSF, synaptic plasticity

Introduction to non-coding RNAs

Cognitive and behavioral dysfunction often arises when the integrity of brain form and function is compromised because of genetic and/or acquired etiological factors. It can manifest during any developmental stage and in adult life and may be associated with a very broad range of neurological and psychiatric conditions, from neural developmental disorders and age-associated neurodegenerative diseases to those occurring at different stages of life. In fact, cognitive and behavioral disorders represent some of the most complex, heterogeneous, and common clinical entities. Although many studies have focused on characterizing the neuroanatomical substrates, neurophysiological correlates, and molecular and genetic bases that underpin cognitive and behavioral processes, an integrated understanding of these emergent functions, and their disorders, has yet to unfold.

Recent advances implicate novel classes of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), which are pervasively transcribed from the genome and enriched in the central nervous system (CNS), and their associated regulatory circuitries in mediating cognitive and behavioral processes and related disorders [1–4]. Hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of ncRNAs have been identified in the human genome by analyses performed utilizing next-generation sequencing technologies and increasingly sophisticated ncRNA prediction algorithms [5, 6]. The majority of these ncRNAs seem to be expressed within the CNS in regional-, cellular-, and subcellular compartment-specific and activity-dependent profiles [7–12]. These ncRNAs have roles in orchestrating neural gene expression and function and gene-environmental interactions and in mediating neural development, neuronal and neural network plasticity and connectivity, stress responses and brain aging [1, 2] (Figure 1). Many investigators have focused on elucidating the life cycles and molecular functions of these diverse classes of ncRNAs and the particular roles they play within the CNS [1, 2, 13]. These studies have uncovered a broad range of cellular pathways and regulatory processes involved in ncRNA biogenesis and maturation, secondary and tertiary structure formation, post-transcriptional processing, dynamic ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex formation, turnover, nuclear-cytoplasmic trafficking, axodendritic targeting and bi-directional transport, and even intercellular transfer [1, 2, 13]. These studies have also revealed a versatile and interrelated spectrum of actions for ncRNAs that includes modulating genomic site-specific and more global epigenetic modifications and transcriptional activity as well as RNA post-transcriptional processing, transport, and translation [14]. All of these ncRNA functions, from regulation of histone and chromatin modifications and transcription to modulation of post-transcriptional RNA dynamics, play critical roles in the molecular mechanisms that underlie cognitive and behavioral processes, including learning and memory (e.g., long-term potentiation [LTP] and long-term depression [LTD]) [15].

Figure 1.

Neurobiology of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs). Depiction of interrelationships between ncRNA life cycle, ncRNA molecular functions, and ncRNA-mediated CNS processes underlying cognition (italics indicates putative roles). Diverse ncRNA subclasses are subject to distinct biogenesis and maturation pathways, fold into functional secondary and tertiary structures, are diversified via post-transcriptional processing, assemble into distinct ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes, and are transported intracellularly and intercellularly through various mechanisms. The molecular functions of these ncRNAs include roles in epigenetic, transcriptional, and post-transcriptional regulation; nuclear subdomain formation; translational control; and modulation of genomic integrity and plasticity. These ncRNAs mediate CNS processes underlying cognition including neural development, adult homeostasis and stress responses, and brain aging and might have roles in trans-neuronal signaling, bidirectional CNS-systemic communication, and multigenerational inheritance of cognitive and behavioral traits.

The central roles played by ncRNAs during evolution, in general, are highlighted by analyses showing that, while the repertoire of protein-coding genes remains relatively constant, the proportion of non-coding sequences in eukaryotic genomes correlates directly with organismal complexity [16] and, further, that there was a dramatic expansion in the inventory of ncRNA genes associated with vertebrate evolution [17]. Similarly, the importance of ncRNAs in mediating the emergence of complex cognitive and behavioral traits is highlighted by analyses showing that neural development and function have evolved mainly through positive selection of non-coding, rather than coding, sequences [18]. Indeed, of 49 regions in the human genome that exhibit accelerated changes in the human lineage since divergence from our common ancestor with the chimpanzee, 47 are non-coding [19]. An ncRNA transcribed from one of these regions, highly accelerated region 1 (HAR1), is primarily expressed during neocortical development in Cajal-Retzius cells, which control radial migration and laminar positioning of pyramidal neurons of the cortical plate. HAR1 is coexpressed with reelin, a critical developmental factor that is implicated in normal cognitive function and in the molecular pathogenesis of diverse cognitive disorders (e.g., neuronal migration defects, autism spectrum disorders [ASDs], schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, epilepsy, stroke, and Alzheimer’s disease [AD]) [20]. Not surprisingly, ncRNAs and associated circuitries also seem to be important for mediating the onset and progression for various CNS disorders including, specifically, those that manifest with cognitive dysfunction across the lifespan [1, 2].

Life cycles and molecular functions of non-coding RNAs

Here we describe the recent emergence of diverse classes of short and long ncRNAs including their biogenesis, functional diversification via post-transcriptional mechanisms (e.g., RNA editing), RNP formation, and intracellular and intercellular transport. We further highlight their roles in transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and epigenetic, regulatory processes, such as X chromosome inactivation and genomic imprinting; nuclear subdomain formation; translational control; and modulation of genomic integrity.

Diverse classes of non-coding RNAs have roles in epigenetic, transcriptional, and post-transcriptional regulation

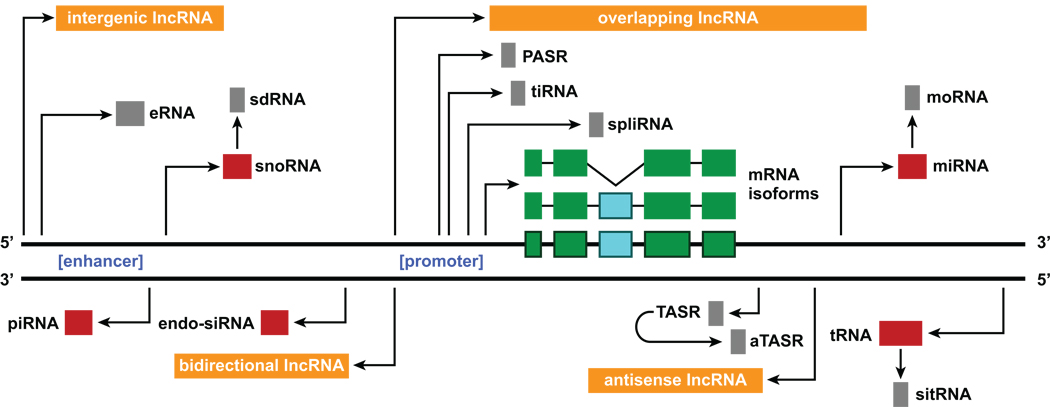

NcRNAs can be categorized into various classes of short ncRNAs such as microRNAs (miRNAs), endogenous short interfering RNAs (endo-siRNAs), PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), and small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) as well as long ncRNAs (lncRNAs; > 200 nucleotides) including those derived from intergenic regions (i.e., lincRNAs) and others organized in distinct configurations relative to protein-coding genes (Figure 2). MiRNAs, the best-characterized class of short ncRNAs, are primarily involved in post-transcriptional regulation of target mRNAs by preventing their translation or sequestering them for storage or degradation via the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) [21]. Endo-siRNAs and piRNAs are similarly involved in post-transcriptional gene regulation and implicated in silencing transposable elements and maintaining genomic integrity in somatic and germ cells [22]. Because of these functions, it is attractive to hypothesize that these ncRNAs modulate the activity of L1 retrotransposons, which play a role in generating neuronal diversity and plasticity in the hippocampus and are deregulated in Rett syndrome (RS) [23, 24]. Each of these three classes of ncRNAs is formed by, and operates via, distinct but interrelated cellular pathways that may include the Dicer ribonuclease and different Argonaute family proteins [25]. In addition, miRNAs, endo-siRNAs, and piRNAs may participate in epigenetic regulation by directing chromatin remodeling events [26]. Moreover, snoRNAs act as guides for the modification of other RNA molecules (e.g., ribosomal RNAs). However, recent evidence demonstrating that the human snoRNA C/D box 115 cluster (HBII-52) regulates alternative splicing of serotonin receptor 2C mRNA suggests novel regulatory roles [27].

Figure 2.

Production of RNAs. Schematic illustrating how diverse RNA species, including protein-coding messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and various classes of short and long non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), may be derived from specific genomic loci and from other ncRNAs. Classes of short ncRNAs with characterized molecular functions (illustrated in red) include transfer RNAs (tRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs), endogenous short interfering RNAs (endo-siRNAs), PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), and small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs). Novel classes of short ncRNAs with poorly characterized molecular functions (illustrated in gray) include (i) those associated with protein-coding gene boundaries (e.g., promoter-associated small RNAs [PASRs], termini-associated short RNAs [TASRs], antisense termini-associated short RNAs [aTASRs], transcription initiation RNAs [tiRNAs], splice-site RNAs [spliRNAs], and enhancer RNAs [eRNAs]) and (ii) others derived from the processing of small ncRNAs (e.g., small RNAs derived from small nucleolar RNAs [sdRNAs], microRNA-offset RNAs [moRNAs], and stress-induced tRNA-derived RNAs [sitRNAs]). Classes of long ncRNAs (lncRNAs; > 200 nucleotides) include those derived from intergenic regions and others organized in bidirectional, antisense, and overlapping configurations relative to protein-coding genes (illustrated in orange).

LncRNAs have a broader spectrum of functions that includes modulation of chromatin structure by recruitment of histone and chromatin modifying complexes to specific genomic sites; regulation of transcription by recruitment of transcription factors; formation of nuclear subdomains associated with post-transcriptional RNA processing (e.g., paraspeckles); nuclear-cytoplasmic transport; and translational control (e.g., local protein synthesis) [28]. Notably, the genomic loci from which lncRNAs are transcribed are important for mediating some of these activities. Particular lncRNAs are found in intergenic regions whereas others are organized in antisense, bi-directional, or overlapping (e.g., intronic) configurations with protein-coding genes and are thought to modulate the expression of these proximally located protein-coding genes (Figure 2). Intriguingly, one recent study showed that a subset of lncRNAs have enhancer-like functions (enhancer-like ncRNAs [elRNAs]) and promote the expression of proximally located protein-coding genes in cis [29]. Remarkably, there are thousands of these elRNA transcripts in the human genome. Furthermore, there are tens of thousands of other lncRNAs that might be involved in regulating more distally located protein-coding genes and almost certainly also ncRNAs, including those located hundreds of kilobase pairs away, or even on different chromosomes in trans [30–33].

In addition, novel ncRNAs are being identified at a rapid pace. These classes of ncRNAs are (i) associated with protein-coding genes (e.g., promoter-associated small RNAs [PASRs], termini-associated short RNAs [TASRs], antisense termini-associated short RNAs [aTASRs], transcription initiation RNAs [tiRNAs], splice-site RNAs [spliRNAs], and enhancer RNAs [eRNAs]); (ii) derived from other small ncRNAs (e.g., small RNAs derived from small nucleolar RNAs [sdRNAs], microRNA-offset RNAs [moRNAs] [34], and stress-induced tRNA-derived RNAs [sitRNAs]); and (iii) derived from structural components of chromosomes (e.g., centrosome-associated RNAs [crasiRNAs] and telomere small RNAs [tel-sRNAs]) [34–43] (Figure 2). Furthermore, recent studies have identified a very large cohort of so-called “dark matter” RNAs that seem to be more abundant than protein-coding RNAs in human cells, including neural cells [44, 45]. However, other findings have called into question the existence of these ncRNAs by suggesting that the data used to characterize them represents artifact arising from processing of pre-mRNAs [46].

Despite this controversy, many ncRNAs are found, often preferentially, in the CNS, where they might play critical roles in mediating cognitive and behavioral processes. For example, eRNAs represent a class of ncRNAs transcribed from ~12,000 enhancers associated with activity-dependent neuronal genes [37]. How the regulation and functional properties of eRNAs compare to those of elRNAs remains to be elucidated; however, these two classes of ncRNAs might be involved in mediating activity-dependent transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation found in the CNS. By contrast, sitRNAs are stress-responsive factors that mediate the assembly of stress granules, key post-transcriptional and epigenetic modulatory factors implicated in CNS diseases [41]. Similarly, tel-sRNAs might be involved in age-associated cognitive disorders because they modulate telomere maintenance and cellular senescence, molecular correlates for aging [43].

RNA editing and post-transcriptional processing of non-coding RNAs

Post-transcriptional mechanisms are responsible for introducing diversity into non-coding transcriptomes, promoting environmental sensitivity and plasticity, and mediating neural development, adult homeostasis and stress responses, brain aging, and disease. Some of these processes are relatively well characterized, such as RNA editing, whereas our appreciation for other processes, including alternative splicing, alternative polyadenylation, and cleavage and secondary 5' capping, is still emerging. For example, a single mature miRNA can exhibit dynamically regulated profiles of length and sequence heterogeneity, largely non-template additions of 3’ uridines or adenosines, referred to as isomiRs [47]. Notably, the majority of miRNAs present in normal brain are isomiRs. This isomiR diversity is probably important for mediating cognitive and behavioral functions, given that significant alterations in isomiR expression are found in the frontal cortex and the striatum of patients with Huntington’s disease (HD) [47].

Editing is a key mechanism for generating flexibility in the information content of ncRNA molecules (as well as protein-coding RNAs and even DNA) [48]. RNA editing refers to nucleoside modifications, including adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) and cytidine-to-uridine (C-to-U) deaminations in RNA molecules, catalyzed by the adenosine deaminase that act on RNA (ADAR) and the apolipoprotein B editing catalytic subunit (APOBEC) families of enzymes, respectively. ADAR1 and 2 are preferentially found in the CNS, and ADAR3 expression is restricted to brain [49, 50]. The targets of A-to-I RNA editing were initially thought to be involved in neuronal cell identity and synaptic transmission [1, 51]. More recent studies have recognized that A-to-I RNA editing occurs primarily in ncRNA transcripts derived from Alu elements [52, 53] and occurs at significant levels in human brain [54]. The preeminence of Alu elements within the human genome and the preferential involvement of RNA editing in the CNS suggests their evolutionary co-adaptation, with Alu elements serving as substrates for RNA editing, which might enhance synaptic efficacy and plasticity associated with memory encoding and consolidation. The essential roles of A-to-I RNA editing are highlighted by the complex behavioral deficits and disease phenotypes associated with ADAR mutations in model organisms [1].

One recent study showed that the levels of A-to-I RNA editing in the human brain are modulated in an age- and gene-specific manner [55], suggesting that selective alterations in RNA editing contribute to brain aging. Moreover, certain single nucleotide polymorphisms at ADAR gene loci are associated with exceptional longevity in humans; in Caenorhabditis elegans, interactions between the RNA editing machinery and ncRNA regulatory networks are partly responsible for regulating lifespan [56, 57]. These observations link brain aging and longevity with ncRNA circuitry and implicate these relationships in determining age-related cognitive changes and disease onset.

The closely related process of DNA editing/recoding refers to deoxycytidine-to-deoxyuridine (dC-to-dU) deaminations, also catalyzed by APOBECs. Like the ADARs, members of the APOBEC family of RNA and DNA editing enzymes, specifically the evolutionarily expanded APOBEC3 subfamily (i.e., B, C, F and G), are expressed in the human CNS, and their levels are modulated by stress response factors [58]. APOBEC activity protects the stability of the genome [59], and it has been suggested that RNA and DNA editing, together, might facilitate recoding of beneficial environmentally-mediated events back into the genomes of post-mitotic neurons, thereby serving as correlates for learning and memory [3]. In fact, factors implicated in linking RNA editing to DNA recoding (e.g., DNA polymerase η) and in epigenetic modulation of synaptic plasticity and memory states are themselves targets of RNA editing, implying that these mechanisms are intimately linked [4]. Moreover, because 8 of the 14 "accelerating" mutations found between human and chimpanzee HAR1 sequences are either A-to-G or C-to-T substitutions [19]—mutations that might be expected from the reintroduction of ADAR-mediated editing events back into the genome—it is intriguing to speculate that the accelerated evolution of HAR1 might be the result of DNA recoding. These mechanisms could be complementary to better-characterized evolutionary processes responsible for promoting nervous system diversity and complexity, such as the accelerated human lineage-specific evolution driven by L1 and other mobile genetic elements, which are major components of human and non-human primate genomes [60, 61]. Studies seeking to uncover the existence of DNA recoding events during the evolution of the CNS and in post-mitotic neurons are currently underway.

Transport of non-coding RNAs

Intracellular trafficking of RNAs in neurons occurs via RNPs and associated granules dynamically delivered from the nucleus to other sites, including synapses [62]. NcRNAs are differentially transported to the synapse, and the post-transcriptional processing and turnover of these transcripts can vary markedly in different subcellular compartments [63]. Intracellular trafficking of RNAs plays key roles in promoting activity-dependent local protein synthesis, which underlies LTP and LTD [64]. The fragile X mental retardation 1 protein (FMRP), encoded by fragile X mental retardation 1 (FMR1), a gene that is mutated in Fragile X syndrome (FXS; a common cause of ASD), is one RBP that is involved in the stabilization, transport, and local synaptic translation of neuronal mRNAs [65]. FMRP is also integrated with the miRNA machinery through direct associations with miRNAs and interactions with miRNA biogenesis (e.g., Dicer) and effector (e.g., RISC) pathways. Moreover, the effects of FMR1 mutations on miRNA activity are linked to impairments in synaptic function and plasticity characteristic of FXS [66]. Associated structures (e.g., neuronal transport granules, stress granules, and processing bodies) mediate transport to axons and dendrites, and include factors responsible for modulating RNA transcription, turnover, post-transcriptional processing, and translation [67]. The ability of RNA regulatory circuitry to dynamically modulate the temporal and spatial profiles of diverse RNA molecules at individual and neighboring synapses might underlie higher-order forms of synaptic plasticity, termed metaplasticity, and associated cognitive and behavioral processes that rely on establishing links between past knowledge and current environmental cues [68].

NcRNAs also promote trafficking of other molecules. For example, non-protein-coding RNA repressor of NFAT (NRON) is a lncRNA that represses nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) signaling by modulating NFAT nuclear-cytoplasmic trafficking [69]. This pathway is involved in mediating cognitive disorders, such as Down syndrome and AD [70, 71].

NcRNAs, along with mRNAs, might act as signaling molecules through local and systemic intercellular transport [72]. MiRNAs can be transferred between adjacent neuronal cells through gap junctions [73]. Another mechanism for the release of ncRNAs is through exosomes, microvesicles secreted by various cell types including neurons. Activity-dependent release of exosomes might be important in signaling across synapses [4, 74]. Evidence for more long distance transport of exosomes, containing ncRNAs, has been found in particular neurological diseases [75, 76]. Exosomes might express recognition molecules that promote selective targeting to recipient cells. Moreover, mechanisms for ncRNA uptake into cells have been identified in C. elegans. Exogenously delivered small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) distribute systemically and are transported into cells via the transmembrane receptor for dsRNA, systemic RNA interference defective (Sid1), where they repress gene expression [77]. A Sid1 homolog, SID1 transmembrane family member 1 (SIDT1), is expressed in human cells [78]. Further, Sidt1 and Sidt2 are expressed in adult mouse brain at sites associated with learning and memory [13]. These observations raise the interesting possibility that ncRNAs serve as signaling molecules for local and long-distance trans-neuronal and bi-directional CNS-systemic communication.

X chromosome inactivation

NcRNAs are implicated in the process of X chromosome inactivation (XCI), which refers to the epigenetic silencing of one X chromosome that occurs in female cells [79]. XCI is mediated by repressive histone modifications and chromatin remodeling directed by the archetypal lncRNA X (inactive)-specific transcript (Xist) and a number of others that are being characterized, including repeat A (RepA), X (inactive)-specific transcript antisense (Tsix), X-inactivation intergenic transcription element (Xite), DXPas34, and non-protein-coding RNA 183 (NCRNA00183/Jpx) [79].

Syndromic and non-syndromic X-linked intellectual disability (XLID) are a heterogeneous group of diseases resulting from different mutations on the X chromosome [80]. These disorders are commonly associated with skewed, rather than random, profiles of XCI in female carriers of these mutations. Moreover, many of the genes mutated in XLID are epigenetic regulatory factors that control neural developmental gene expression [81]. Not only do ncRNAs modulate these same genes, but they might do so through direct interactions with these epigenetic factors [14]. In fact, various classes of ncRNAs have been implicated in recruiting relatively generic chromatin modifying complexes and DNA methyltransferases to particular genomic loci [14].

Genomic imprinting

NcRNAs are involved in, and also subject to, genomic imprinting—a mechanism for epigenetic gene silencing. Imprinting is mediated not only by DNA methylation and histone modifications but also by ncRNAs [82]. LncRNAs, such as antisense of IGF2R RNA (Air) and KCNQ1 overlapping transcript 1 (Kcnq1ot1), silence large genomic regions through interactions with chromatin regulatory factors to establish repressive chromatin environments at imprinted loci. Imprinting in the brain exhibits complex temporal, spatial, cell type-specific, and sex-specific, and inter-individual profiles [83–85]. Protein-coding genes and ncRNAs are subject to imprinting and therefore can be expressed monoallelically in a parent-of-origin-dependent manner. This phenomenon is associated with proper neural development and function [86]. For example, the epigenetic regulatory factors—alpha thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked, methyl CpG binding protein 2 (MECP2), CCCTC-binding factor, and cohesin—that are linked to the development of several cognitive and behavioral disorders have roles in silencing the imprinted lncRNA, H19, as well as other imprinted genes during postnatal brain developmental critical periods [87]. Other cognitive and behavioral disorders, such as Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) and Angelman syndromes (AS), are associated with perturbations in imprinting. They might even result directly from the disruption of ncRNA circuitry. For example, a microdeletion of the snoRNA C/D box 116 cluster (HBII-85) and HBII-52 snoRNA clusters has been linked to the development of PWS in a subgroup of patients [88].

Central nervous system processes mediated by non-coding RNAs

NcRNAs are implicated in promoting neural stem cell (NSC) maintenance and maturation, including neurogenesis and gliogenesis [28, 89]. These processes are critical during development, and adult hippocampal neurogenesis is also involved in learning and memory [90]. One interesting ncRNA that regulates adult hippocampal neurogenesis is the small modulatory double-stranded RNA derived from the genomic NRSE/RE1 sequence, dsNRSE. This motif is bound by RE1-silencing transcription factor (REST), which is associated with a range of neural developmental and neurodegenerative disorders (Box 1) [91]. Expression of dsNRSE in adult hippocampal NSCs promotes neurogenesis by positively regulating NRSE/RE1-associated genes [92]. Age-associated changes in adult neurogenesis might, in part, be responsible for mediating concurrent alterations in cognitive functions and associated disorders, thus further implicating ncRNA dynamics in these processes [93].

Box 1. REST and CoREST are highly integrated with ncRNA networks.

The master transcriptional and epigenetic regulatory factors, REST and REST corepressor 1 (CoREST), are closely linked and highly integrated with ncRNA networks [91, 102]. This circuitry plays important roles in mediating neural development, neuronal and neural network plasticity and connectivity and stress responses. REST and CoREST bind, either alone or in concert, to thousands of RE1 and non-RE1 sequences in a neural developmental stage, cell selective, and activity-dependent manner. They recruit a spectrum of transcriptional and epigenetic cofactors to these sites, forming distinct macromolecular complexes with context-specific functions including gene activation, repression, and long-term gene silencing. These cofactors include subunits of the Mediator complex (e.g., MED19 and MED26), which is essential for RNA polymerase II activity; methyl-CpG binding proteins (e.g., MECP2); and histone (e.g., histone deacetylases 1 and 2 (HDAC1 and HDAC2)) and chromatin remodeling enzymes (e.g., BAF57, BRG1, and BAF170). REST and CoREST thereby regulate the transcriptional and epigenetic status of target genomic loci encoding factors responsible for diverse nervous system functions including growth factors, axon guidance cues, ion channels, neurotransmitter receptors, synaptic vesicle proteins, and cytoskeletal and extracellular matrix components. REST and CoREST also modulate genomic loci encompassing ncRNAs (e.g., miRNAs and lncRNAs). Not only do REST and CoREST regulate the expression of these ncRNAs, but ncRNAs also regulate REST and CoREST expression through complex feedback mechanisms. REST- and CoREST-regulated miRNAs are also modulated cooperatively by CREB, which couples synaptic activity to long-term changes in neuronal plasticity underlying learning and memory [96]. LncRNAs have been implicated in directing REST and CoREST chromatin-remodeling complexes to their genomic sites of action. These observations illustrate how the expression and function of ncRNAs are intimately linked to REST and CoREST. Emerging observations suggest additional interrelationships exist between ncRNA circuitry and these seminal factors. Not only does REST bind to Mediator subunits directly, but REST and CoREST target members of Mediator and cohesin complexes [91]. In turn, cohesin and Mediator promote DNA looping and activity-dependent neuronal enhancer/promoter interactions that may influence the regulation and functions of novel ncRNAs associated with these elements (eRNAs, elRNAs, PASRs). The REST and CoREST binding partners MECP2 and HDAC1 have previously been linked to the mechanisms underlying learning and memory and to specific developmental cognitive disorders (e.g. RS) and very recently have also been implicated in modulating L1 retrotransposition activity in neural progenitors—a developmental process that is deregulated in RS—highlighting the complex interplay that exists between REST, CoREST, and associated factors and ncRNAs in mediating cognitive disorders [24, 102].

NcRNAs are also involved in the mechanisms that underlie neuronal and neural network plasticity and connectivity [63]. In fact, a recent study reported experiments employing an inducible strategy to selectively delete Dicer1, which is responsible for miRNA biogenesis, in the adult mouse forebrain [94]. Mutant animals exhibited loss of brain-specific miRNAs after introduction of the Dicer1 gene mutation, resulting in alterations of dendritic spine morphology, abnormal levels of synaptic plasticity-related proteins and alterations of learning and memory. Moreover, miRNA expression profiles are regulated by LTP induction [11, 95] and by factors with key roles in learning and memory, such as cAMP responsive element binding protein (CREB) [96]. In turn, these miRNAs modulate CREB levels, thereby forming bi-directional feedback loops [96]. In addition, protein kinase M ζ (PKM ζ), a core molecule for long-term memory storage and retrieval, is a predicted target of many human miRNAs (www.microrna.org; August 2010). MiRNAs can also be localized in axons and dendrites, where they might participate in synaptic remodeling and memory formation by controlling local protein synthesis. For example, miR-134 modulates the size of dendritic spines by regulating post-synaptic translation of LIM domain kinase 1 (LIMK1) [97], a factor implicated in William’s syndrome and associated cognitive deficits. Interestingly, miR-134 is also involved in a pathway involving sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) that regulates synaptic plasticity [98]. SIRT1 promotes synaptic plasticity by modulating miR-134, which, in turn, controls CREB expression. SIRT1 deficiency impairs synaptic plasticity by releasing miR-134 from repression, thus resulting in the downregulation of CREB. Because SIRT1 is a stress response factor that promotes longevity by regulating different cell survival pathways, it is attractive to speculate that this pathway is involved in brain aging and associated cognitive changes.

An increasing number of studies implicate miRNAs in the pathophysiology of diverse cognitive disorders. For example, a neuronal activity-dependent miRNA, miR-132, modulates the expression of MECP2, a factor mutated in RS and other ASDs. Similarly, miR-101 and miR-29a/b-1 regulate amyloid precursor protein and β-site APP-cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) expression, respectively [99, 100]. Conversely, amyloid β (Aβ) might induce neuronal miRNA deregulation and cellular events that lead to AD [101]. Deregulation of miRNAs is also observed in HD and mediated partly through REST (Box 1) [102].

LncRNAs are implicated in neuronal and neural network plasticity and connectivity [3, 4]. One interesting lncRNA is DLX6 antisense RNA 1 (Dlx6-AS/Evf2), which is transcribed from the distal-less homeobox 5/6 (Dlx5/6) ultraconserved enhancer region. It promotes the recruitment of transcription factors to adjacent protein-coding gene loci [103]. Animal models engineered to express Evf2 mutations [103] exhibit anomalies in synaptic activity resulting from aberrant formation of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic circuitry in the hippocampus and dentate gyrus. Moreover, ablation and overexpression of the metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (Malat1/Neat2) lncRNA in cultured hippocampal neurons result in decreased and increased synaptic density, respectively [104]. Intriguingly, the function of this lncRNA is associated with serine/arginine (SR)-rich proteins, a family of factors involved in various aspects of RNA metabolism [105]. These observations suggest that lncRNAs might orchestrate the fidelity of synaptic plasticity and neural connectivity by dynamically monitoring and integrating multiple transcriptional and post-transcriptional events.

Other lncRNAs modulate synaptic plasticity and are linked to cognitive disorders. Rodent brain cytoplasmic RNA 1 (BC1) and primate brain cytoplasmic RNA 1 (BCYRN1/BC200) act as negative regulators of translation in post-synaptic compartments, where they modulate local protein synthesis [106]. BC1−/− mice exhibit abnormal cognitive and behavioral phenotypes [107]. BC200 exhibits abnormal subcellular localization and expression levels in brain regions from AD patients that correlate with disease severity [108]. 17A, a lncRNA embedded in the GABA B receptor, 2 (GABBR2) locus is deregulated in brain tissues from patients with AD [109]. 17A influences intracellular signaling pathways downstream of the associated GABA receptor by regulating its alternative splicing. In addition, 17A is expressed in response to inflammatory stimuli, and it promotes Aβ secretion and increases the pathologic Aβ42:Aβ40 ratio [109]. Another lncRNA linked to AD is BACE1-AS, which is transcribed in an antisense orientation to the BACE1 gene and modulates BACE1 expression [110]. BACE1-AS levels are also increased an APP mouse model of AD and in tissues from AD patients. Exposure to harmful stimuli, including reactive oxygen species, chronic hypoxia and Aβ42, enhances expression and nuclear-cytoplasmic translocation of BACE1-AS. LncRNAs are associated with cognitive and behavioral disorders in addition to AD [28]. For example, HAR1 expression is decreased in the striatum of patients with HD, mediated again by REST [111]. Further, disrupted in schizophrenia 2 (DISC2) is implicated in neuropsychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, mood disorders, and ASDs; FMR1 antisense RNA 1 (FMR4/ASFMR1) is associated with FXS; and UBE3A antisense RNA (UBE3A-AS) might be linked to AS [28]. Additional lncRNAs are associated with epilepsy and stroke [112, 113].

Intriguingly, lncRNAs derived from the imprinted GNAS locus might have roles in cognitive and behavioral dysfunction associated with GNAS mutations [114]. One possibility is that neuroendocrine secretory protein antisense (NESPAS), an lncRNA derived from this locus, modulates neuroendocrine secretory protein 55 (NESP55), a neurosecretory factor prominently expressed in the locus coeruleus-noradrenergic system [115]. This system is an important mediator of state-dependent neural network activity and associated neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders [116]. These observations suggest that RNA regulatory circuitry, in addition to regulating synaptic plasticity, might also mediate rapid and widespread neural network remodeling to facilitate more global behavioral responses to environmental challenges.

Brain aging and related cognitive phenotypes are associated with alterations in synaptic and neural network connectivity, plasticity and stress responses that can be mediated by ncRNAs [117]. One interesting example is the heat shock RNA 1 (HSR1), which plays a key role in promoting the cytoprotective heat shock response that is linked to neural development and brain aging and to the molecular pathogenesis of diverse neurodegenerative disorders [118]. HSR1 mediates the activation of heat shock transcription factor 1 (HSF1), by inducing its trimerization and associated acquisition of its specific DNA-binding activity, highlighting the ability of ncRNAs to act as environmental biosensors and to rapidly transduce salient informational cues into downstream functional pathways via effects mediated by changes in secondary and tertiary structures [119]. Further, the deployment of various classes of ncRNAs might change with age (e.g., lincRNAs involved in p53-mediated cell stress pathways [120] and lncRNAs induced in response to DNA damage [121]). Indeed, the expression levels of miRNAs in the brain change with advancing age and have been linked to molecular processes underlying brain aging and neurodegeneration [122, 123].

Concluding remarks

The life cycles, molecular functions, and biophysical and other features of ncRNA molecules seem to imbue ncRNA regulatory networks with the operational capacity, modularity, flexibility and environmental responsiveness, robustness, and evolvability necessary for orchestrating higher-order CNS processes including emergent cognitive and behavioral functions. In this review, we examined how ncRNAs mediate CNS functions, from neural development and aging to plasticity and stress responses, by orchestrating dynamic and highly environmentally responsive temporal and spatial profiles of gene expression as well as coordinating allele-, sex-, and associated parent-of-origin-specific effects. We suggest that it is likely that emerging classes of ncRNAs play complementary roles in mediating CNS processes, by further coordinating genomic site-specific and more global epigenetic modifications and transcriptional activity; RNA post-transcriptional processing, transport, and translation; as well as genomic stability and plasticity.

We also highlighted how alterations in ncRNAs and related factors are associated with the pathophysiology of cognitive disorders. We speculate that defects in ncRNA circuitry are likely to represent the principal pathogenic mechanisms underlying many of these disorders. For example, transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and epigenetic deregulation are hallmarks of neural development and neurodegenerative diseases; and, multiple layers of ncRNA circuitry are implicated in mediating these processes. Further, RNA dominant toxicity is responsible for the pathogenesis of a subset of neural developmental and neurodegenerative expansion repeat disorders that manifest with cognitive and behavioral dysfunction, including those in which tandem repeats occur in non-coding regions and are known to encode ncRNAs [124]. NcRNA circuitry might be particularly relevant in these and other disorders caused by mutations (or associated with polymorphisms) in non-coding regions, because these sites might affect the deployment and function of ncRNA circuitry.

One intriguing challenge for future research endeavors is to better characterize ncRNA trafficking between adjacent and more distributed cell types within the brain and between different organ systems. We examined evidence suggesting the presence of multiple routes of trans-neuronal and systemic ncRNA signaling; however, the functions of these transported ncRNAs remain largely unexplored. It is tempting to speculate that this form of ncRNA signaling could promote the activity-dependent oscillatory synchrony of distributed neuronal ensembles that is required for environmentally mediated cognitive and behavioral repertoires. Dissemination through the systemic circulation might promote bidirectional neural-immune axis communication and transmission of experience-dependent modified somatic RNAs (e.g., via activity-dependent neuronal RNA editing and associated DNA recoding) to the germ-line for multigenerational inheritance of higher-order cognitive and behavioral traits.

These overall observations imply that the fidelity of ncRNA circuitry is compromised by individual or cumulative genetic and environmental factors throughout the lifespan leading to potentially reversible and to irreversible changes in brain structure and function. Evolving scientific initiatives offer great promise for defining the underlying molecular basis of ncRNA-mediated brain-behavior relationships and for identifying novel biomarkers, molecular therapeutic targets, signatures of pre-clinical brain dysfunction, disease progression and more sensitive indices of early therapeutic responsiveness for cognitive disorders at different stages of the life cycle (Box 2).

Box 2. Outstanding questions.

What is the full range of neurobiological functions (and associated mechanisms of actions) of novel and emerging classes of short and long ncRNAs?

Do these ncRNAs play causal, rather than correlative, roles in the molecular pathogenesis of various types of cognitive dysfunction?

Does our emerging understanding of ncRNAs begin to explain why genome-wide association studies often identify disease-associated variants in non-coding regions and why focusing on protein-coding gene loci has largely failed to reveal the genetic basis of common cognitive disorders?

Can we translate our emerging understanding of ncRNA pathobiology in cognitive disorders into more effective strategies for diagnosis and for monitoring disease progression and response to treatment?

Will novel therapeutic agents targeting ncRNAs and related biogenesis and effector pathways in the nervous system, or systemically, prove to be viable treatments for correcting neural developmental abnormalities, promoting synaptic and neural network plasticity, modulating stress responses, and preventing brain aging; thereby preserving or even enhancing and restoring lost cognitive functions?

Acknowledgments

We regret that space constraints have prevented the citation of many relevant and important references. M.F.M. is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NS38902, MH66290, NS071571), as well as by the Roslyn and Leslie Goldstein, Harold and Isabel Feld, Mildred and Bernard H. Kayden, F. M. Kirby, and Alpern Family Foundations.

Glossary

- Chromatin

genomic DNA wrapped around histone protein octamers (i.e., nucleosomes), non-histone proteins, and associated factors forming a compact “beads-on-a-string” structure that is dynamically rearranged within the cell nucleus in an environmentally responsive manner.

- Chromatin remodeling complexes

macromolecular assemblies of enzymes and associated factors that read, write, and execute chromatin regulatory programs such as post-translational modifications of histone proteins, repositioning of nucleosomes, and altering higher-order chromatin structure (e.g., entire chromosomal regions).

- Epigenetics

highly interrelated and environmentally responsive molecular processes including DNA methylation, histone and chromatin modifications, ncRNA deployment, RNA editing and nuclear reorganization that are responsible for regulating genomic structure and function and for establishing and maintaining metastable cellular memory states (e.g., profiles of gene transcription, imprinting, and X chromosome inactivation).

- Non-coding RNAs

diverse classes of RNA molecules not translated into proteins that possess intricate regulatory and structural functions.

- Non-coding RNA circuitry

molecular components associated with ncRNA biogenesis and function (e.g., RBPs and Argonaute proteins), diversification (e.g., RNA editing enzymes), and intracellular (e.g., molecular motors) and extracellular trafficking (e.g., gap junctions, exosomes and systemic RNA receptors).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mehler MF, Mattick JS. Noncoding RNAs and RNA editing in brain development, functional diversification, and neurological disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:799–823. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00036.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehler MF. Epigenetic principles and mechanisms underlying nervous system functions in health and disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 2008;86:305–341. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mattick JS, Mehler MF. RNA editing, DNA recoding and the evolution of human cognition. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mercer TR, et al. Noncoding RNAs in Long-Term Memory Formation. Neuroscientist. 2008;14:434–445. doi: 10.1177/1073858408319187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Majer A, Booth SA. Computational methodologies for studying non-coding RNAs relevant to central nervous system function and dysfunction. Brain Res. 2010;1338:131–145. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.03.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang JH, et al. deepBase: a database for deeply annotating and mining deep sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D123–D130. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mercer TR, et al. Specific expression of long noncoding RNAs in the mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:716–721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706729105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ponjavic J, et al. Genomic and transcriptional co-localization of protein-coding and long non-coding RNA pairs in the developing brain. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000617. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mercer TR, et al. Long noncoding RNAs in neuronal-glial fate specification and oligodendrocyte lineage maturation. BMC Neurosci. 2010;11:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lau P, et al. Identification of dynamically regulated microRNA and mRNA networks in developing oligodendrocytes. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:11720–11730. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1932-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park CS, Tang SJ. Regulation of microRNA expression by induction of bidirectional synaptic plasticity. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2009;38:50–56. doi: 10.1007/s12031-008-9158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Natera-Naranjo O, et al. Identification and quantitative analyses of microRNAs located in the distal axons of sympathetic neurons. RNA. 2010;16:1516–1529. doi: 10.1261/rna.1833310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dinger ME, et al. RNAs as extracellular signaling molecules. J Mol Endocrinol. 2008;40:151–159. doi: 10.1677/JME-07-0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattick JS, et al. RNA regulation of epigenetic processes. Bioessays. 2009;31:51–59. doi: 10.1002/bies.080099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franklin TB, Mansuy IM. The prevalence of epigenetic mechanisms in the regulation of cognitive functions and behaviour. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2010;20:441–449. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heimberg AM, et al. MicroRNAs and the advent of vertebrate morphological complexity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:2946–2950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712259105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taft RJ, et al. The relationship between non-protein-coding DNA and eukaryotic complexity. Bioessays. 2007;29:288–299. doi: 10.1002/bies.20544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haygood R, et al. Contrasts between adaptive coding and noncoding changes during human evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:7853–7857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911249107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollard KS, et al. An RNA gene expressed during cortical development evolved rapidly in humans. Nature. 2006;443:167–172. doi: 10.1038/nature05113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tamura Y, et al. Epigenetic aberration of the human REELIN gene in psychiatric disorders. Mol. Psychiatry. 2007;12:519, 593–600. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krol J, et al. The widespread regulation of microRNA biogenesis, function and decay. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010;11:597–610. doi: 10.1038/nrg2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamura K, Lai EC. Endogenous small interfering RNAs in animals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:673–678. doi: 10.1038/nrm2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coufal NG, et al. L1 retrotransposition in human neural progenitor cells. Nature. 2009;460:1127–1131. doi: 10.1038/nature08248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muotri AR, et al. L1 retrotransposition in neurons is modulated by MeCP2. Nature. 2010;468:443–446. doi: 10.1038/nature09544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou R, et al. Comparative analysis of argonaute-dependent small RNA pathways in Drosophila. Mol. Cell. 2008;32:592–599. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verdel A, et al. Common themes in siRNA-mediated epigenetic silencing pathways. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2009;53:245–257. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082691av. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kishore S, Stamm S. The snoRNA HBII-52 regulates alternative splicing of the serotonin receptor 2C. Science. 2006;311:230–232. doi: 10.1126/science.1118265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qureshi IA, et al. Long non-coding RNAs in nervous system function and disease. Brain Res. 2010;1338:20–35. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.03.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orom UA, et al. Long noncoding RNAs with enhancer-like function in human cells. Cell. 2010;143:46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kapranov P, et al. RNA maps reveal new RNA classes and a possible function for pervasive transcription. Science. 2007;316:1484–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.1138341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Birney E, et al. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature. 2007;447:799–816. doi: 10.1038/nature05874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carninci P, et al. The transcriptional landscape of the mammalian genome. Science. 2005;309:1559–1563. doi: 10.1126/science.1112014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katayama S, et al. Antisense transcription in the mammalian transcriptome. Science. 2005;309:1564–1566. doi: 10.1126/science.1112009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taft RJ, et al. Nuclear-localized tiny RNAs are associated with transcription initiation and splice sites in metazoans. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:1030–1034. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taft RJ, et al. Evolution, biogenesis and function of promoter-associated RNAs. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2332–2338. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.15.9154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belostotsky D. Exosome complex and pervasive transcription in eukaryotic genomes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2009;21:352–358. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim TK, et al. Widespread transcription at neuronal activity-regulated enhancers. Nature. 2010;465:182–187. doi: 10.1038/nature09033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kapranov P, et al. New class of gene-termini-associated human RNAs suggests a novel RNA copying mechanism. Nature. 2010;466:642–646. doi: 10.1038/nature09190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taft RJ, et al. Tiny RNAs associated with transcription start sites in animals. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:572–578. doi: 10.1038/ng.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taft RJ, et al. Small RNAs derived from snoRNAs. RNA. 2009;15:1233–1240. doi: 10.1261/rna.1528909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emara MM, et al. Angiogenin-induced tRNA-derived stress-induced RNAs promote stress-induced stress granule assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:10959–10968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.077560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alliegro MC, Alliegro MA. Centrosomal RNA correlates with intron-poor nuclear genes in Spisula oocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:6993–6997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802293105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cao F, et al. Dicer independent small RNAs associate with telomeric heterochromatin. RNA. 2009;15:1274–1281. doi: 10.1261/rna.1423309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cui P, et al. A comparison between ribo-minus RNA-sequencing and polyA-selected RNA-sequencing. Genomics. 2010;96:259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kapranov P, et al. The majority of total nuclear-encoded non-ribosomal RNA in a human cell is 'dark matter' un-annotated RNA. BMC Biol. 2010;8:149. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Bakel H, et al. Most "dark matter" transcripts are associated with known genes. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000371. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marti E, et al. A myriad of miRNA variants in control and Huntington's disease brain regions detected by massively parallel sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.St Laurent G, 3rd, et al. Enhancing non-coding RNA information content with ADAR editing. Neurosci. Lett. 2009;466:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jacobs MM, et al. ADAR1 and ADAR2 expression and editing activity during forebrain development. Dev. Neurosci. 2009;31:223–237. doi: 10.1159/000210185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Melcher T, et al. RED2, a brain-specific member of the RNA-specific adenosine deaminase family. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:31795–31798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.31795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nishikura K. Functions and regulation of RNA editing by ADAR deaminases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010;79:321–349. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060208-105251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li JB, et al. Genome-wide identification of human RNA editing sites by parallel DNA capturing and sequencing. Science. 2009;324:1210–1213. doi: 10.1126/science.1170995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hundley HA, Bass BL. ADAR editing in double-stranded UTRs and other noncoding RNA sequences. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2010;35:377–383. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kawahara Y, et al. Frequency and fate of microRNA editing in human brain. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:5270–5280. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nicholas A, et al. Age-related gene-specific changes of A-to-I mRNA editing in the human brain. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Montano M, Long K. RNA surveillance-An emerging role for RNA regulatory networks in aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sebastiani P, et al. RNA editing genes associated with extreme old age in humans and with lifespan in C. elegans. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e8210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang YJ, et al. Expression and regulation of antiviral protein APOBEC3G in human neuronal cells. J. Neuroimmunol. 2009;206:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Conticello SG. The AID/APOBEC family of nucleic acid mutators. Genome Biol. 2008;9:229. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-6-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xing J, et al. Mobile DNA elements in primate and human evolution. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2007 Suppl 45:2–19. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Britten RJ. Transposable element insertions have strongly affected human evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:19945–19948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014330107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vuppalanchi D, et al. Regulation of mRNA transport and translation in axons. Results Probl. Cell Differ. 2009;48:193–224. doi: 10.1007/400_2009_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schratt G. microRNAs at the synapse. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009;10:842–849. doi: 10.1038/nrn2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bramham CR. Local protein synthesis, actin dynamics, and LTP consolidation. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2008;18:524–531. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheever A, Ceman S. Translation regulation of mRNAs by the fragile X family of proteins through the microRNA pathway. RNA Biol. 2009;6:175–178. doi: 10.4161/rna.6.2.8196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li X, Jin P. Macro role(s) of microRNAs in fragile X syndrome? Neuromolecular Med. 2009;11:200–207. doi: 10.1007/s12017-009-8081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Anderson P, Kedersha N. RNA granules: post-transcriptional and epigenetic modulators of gene expression. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:430–436. doi: 10.1038/nrm2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mockett BG, Hulme SR. Metaplasticity: new insights through electrophysiological investigations. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2008;7:315–336. doi: 10.1142/s0219635208001782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Willingham AT, et al. A strategy for probing the function of noncoding RNAs finds a repressor of NFAT. Science. 2005;309:1570–1573. doi: 10.1126/science.1115901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arron JR, et al. NFAT dysregulation by increased dosage of DSCR1 and DYRK1A on chromosome 21. Nature. 2006;441:595–600. doi: 10.1038/nature04678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abdul HM, et al. Cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease is associated with selective changes in calcineurin/NFAT signaling. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:12957–12969. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1064-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Benner SA. Extracellular 'communicator RNA'. FEBS Lett. 1988;233:225–228. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80431-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Katakowski M, et al. Functional microRNA is transferred between glioma cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8259–8263. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Smalheiser NR. Exosomal transfer of proteins and RNAs at synapses in the nervous system. Biol. Direct. 2007;2:35. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-2-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen C, et al. Microfluidic isolation and transcriptome analysis of serum microvesicles. Lab. Chip. 2010;10:505–511. doi: 10.1039/b916199f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Skog J, et al. Glioblastoma microvesicles transport RNA and proteins that promote tumour growth and provide diagnostic biomarkers. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;10:1470–1476. doi: 10.1038/ncb1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Feinberg EH, Hunter CP. Transport of dsRNA into cells by the transmembrane protein SID-1. Science. 2003;301:1545–1547. doi: 10.1126/science.1087117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Duxbury MS, et al. RNA interference: a mammalian SID-1 homologue enhances siRNA uptake and gene silencing efficacy in human cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;331:459–463. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lee JT. The X as model for RNA's niche in epigenomic regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a003749. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gecz J, et al. The genetic landscape of intellectual disability arising from chromosome X. Trends Genet. 2009;25:308–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.van Bokhoven H, Kramer JM. Disruption of the epigenetic code: an emerging mechanism in mental retardation. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010;39:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bartolomei MS. Genomic imprinting: employing and avoiding epigenetic processes. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2124–2133. doi: 10.1101/gad.1841409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Davies W, et al. Imprinted gene expression in the brain. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2005;29:421–430. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gregg C, et al. Sex-Specific Parent-of-Origin Allelic Expression in the Mouse Brain. Science. 2010;329:682–685. doi: 10.1126/science.1190831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gregg C, et al. High-Resolution Analysis of Parent-of-Origin Allelic Expression in the Mouse Brain. Science. 2010;329:643–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1190830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Davies W, et al. What are imprinted genes doing in the brain? Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2008;626:62–70. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-77576-0_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cunningham MD, et al. Chromatin modifiers, cognitive disorders, and imprinted genes. Dev. Cell. 2010;18:169–170. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sahoo T, et al. Prader-Willi phenotype caused by paternal deficiency for the HBII-85 C/D box small nucleolar RNA cluster. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:719–721. doi: 10.1038/ng.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lau P, Hudson LD. MicroRNAs in neural cell differentiation. Brain Res. 2010;1338:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Aimone JB, et al. Adult neurogenesis: integrating theories and separating functions. Trends Cogn Sci. 2010;14:325–337. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Qureshi IA, et al. REST and CoREST are transcriptional and epigenetic regulators of seminal neural fate decisions. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:4477–4486. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.22.13973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kuwabara T, et al. The NRSE smRNA specifies the fate of adult hippocampal neural stem cells. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser (Oxf) 2005:87–88. doi: 10.1093/nass/49.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lazarov O, et al. When neurogenesis encounters aging and disease. Trends Neurosci. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Konopka W, et al. MicroRNA Loss Enhances Learning and Memory in Mice. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:14835–14842. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3030-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wibrand K, et al. Differential regulation of mature and precursor microRNA expression by NMDA and metabotropic glutamate receptor activation during LTP in the adult dentate gyrus in vivo. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2010;31:636–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07112.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wu J, Xie X. Comparative sequence analysis reveals an intricate network among REST, CREB and miRNA in mediating neuronal gene expression. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R85. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-9-r85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Schratt GM, et al. A brain-specific microRNA regulates dendritic spine development. Nature. 2006;439:283–289. doi: 10.1038/nature04367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gao J, et al. A novel pathway regulates memory and plasticity via SIRT1 and miR-134. Nature. 2010;466:1105–1109. doi: 10.1038/nature09271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Vilardo E, et al. MicroRNA-101 regulates amyloid precursor protein expression in hippocampal neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:18344–18351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.112664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hebert SS, et al. Loss of microRNA cluster miR-29a/b-1 in sporadic Alzheimer's disease correlates with increased BACE1/beta-secretase expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:6415–6420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710263105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Schonrock N, et al. Neuronal microRNA deregulation in response to Alzheimer's disease amyloid-beta. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Qureshi IA, Mehler MF. Regulation of non-coding RNA networks in the nervous system--what's the REST of the story? Neurosci. Lett. 2009;466:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.07.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bond AM, et al. Balanced gene regulation by an embryonic brain ncRNA is critical for adult hippocampal GABA circuitry. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1020–1027. doi: 10.1038/nn.2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bernard D, et al. A long nuclear-retained non-coding RNA regulates synaptogenesis by modulating gene expression. EMBO J. 2010;29:3082–3093. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tripathi V, et al. The nuclear-retained noncoding RNA MALAT1 regulates alternative splicing by modulating SR splicing factor phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. 2010;39:925–938. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lin D, et al. Translational control by a small RNA: dendritic BC1 RNA targets the eukaryotic initiation factor 4A helicase mechanism. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:3008–3019. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01800-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lewejohann L, et al. Role of a neuronal small non-messenger RNA: behavioural alterations in BC1 RNA-deleted mice. Behav Brain Res. 2004;154:273–289. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mus E, et al. Dendritic BC200 RNA in aging and in Alzheimer's disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:10679–10684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701532104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Massone S, et al. 17A, a novel non-coding RNA, regulates GABA B alternative splicing and signaling in response to inflammatory stimuli and in Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Faghihi MA, et al. Expression of a noncoding RNA is elevated in Alzheimer's disease and drives rapid feed-forward regulation of beta-secretase. Nat. Med. 2008;14:723–730. doi: 10.1038/nm1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Johnson R, et al. The Human Accelerated Region 1 noncoding RNA is repressed by REST in Huntington's disease. Physiol. Genomics. 2010 doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00019.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Qureshi IA, Mehler MF. Epigenetic mechanisms underlying human epileptic disorders and the process of epileptogenesis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010;39:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Qureshi IA, Mehler MF. The Emerging Role of Epigenetics in Stroke: II. RNA Regulatory Circuitry. Arch. Neurol. 2010;67:1435–1441. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Krechowec S, Plagge A. Physiological dysfunctions associated with mutations of the imprinted Gnas locus. Physiology (Bethesda) 2008;23:221–229. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00010.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Plagge A, et al. Imprinted Nesp55 influences behavioral reactivity to novel environments. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:3019–3026. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.8.3019-3026.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Berridge CW, Waterhouse BD. The locus coeruleus-noradrenergic system: modulation of behavioral state and state-dependent cognitive processes. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2003;42:33–84. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(03)00143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Burke SN, Barnes CA. Senescent synapses and hippocampal circuit dynamics. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Shamovsky I, et al. RNA-mediated response to heat shock in mammalian cells. Nature. 2006;440:556–560. doi: 10.1038/nature04518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.St Laurent G, 3rd, Wahlestedt C. Noncoding RNAs: couplers of analog and digital information in nervous system function? Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:612–621. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Huarte M, et al. A large intergenic noncoding RNA induced by p53 mediates global gene repression in the p53 response. Cell. 2010;142:409–419. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wang X, et al. Induced ncRNAs allosterically modify RNA-binding proteins in cis to inhibit transcription. Nature. 2008;454:126–130. doi: 10.1038/nature06992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Persengiev S, et al. Genome-wide analysis of miRNA expression reveals a potential role for miR-144 in brain aging and spinocerebellar ataxia pathogenesis. Neurobiol. Aging. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.An J, et al. Identifying co-regulating microRNA groups. J. Bioinform. Comput. Biol. 2010;8:99–115. doi: 10.1142/s0219720010004574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Nakamori M, Thornton C. Epigenetic changes and non-coding expanded repeats. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010;39:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]