Abstract

Objective

To determine the mechanism of action of IL-27 against rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods

Adenovirus containing IL-27 transcript was constructed and was locally delivered into the ankles of collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) mice. Progression of arthritis was assessed in treated versus untreated mice by measuring ankle circumference and through histological analysis. IL-17 and its downstream targets as well as cytokines promoting TH-17 cell differentiation were quantified by ELISA in CIA ankles locally expressing adenoviral IL-27 versus controls. Ankles from both treatment groups were immunostained for neutrophil and monocyte migration. Last, vascularization was quantified by histology and by determining ankle hemoglobin levels.

Results

Our results demonstrate that ectopic expression of IL-27 in CIA ameliorates inflammation, lining hypertrophy, and bone erosion compared to the control group. Serum and joint IL-17 levels were significantly reduced in the IL-27 treatment group compared to controls. Two of the main cytokines which induce TH-17 cell differentiation and IL-17 downstream target molecules were greatly downregulated in CIA ankles receiving forced expression of IL-27. The control mice had higher levels of vascularization and monocyte trafficking compared to those mice ectopically expressing IL-27.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that increased IL-27 levels relieve arthritis in CIA ankles. This amelioration of arthritis involves a reduction in CIA serum and joint IL-17 levels and results in decreased IL-17-mediated monocyte recruitment and angiogenesis. Hence, IL-27 may be a therapeutic target in RA.

Keywords: IL-27, collagen induced arthritis, IL-17, IL-1 and IL-6

IL-17 is found in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) synovial fluid and in the T cell rich areas of RA synovial tissue (ST)(1, 2). TH-17 cells which are derived from RA synovial tissue, are significantly increased in RA synovial fluid compared to RA or normal peripheral blood (3). Our recent studies have shown that IL-17 mediates angiogenesis in RA synovial fluid through ligation to IL-17 receptor (R)C (4). IL-17 can also contribute to the pathogenesis of RA by inducing monocyte migration into the inflamed synovial tissue (5, 6).

IL-17 plays a profound role in the pathogenesis of experimental arthritis. CIA is markedly reduced in IL-17-/- mice (7) and treatment of the experimental CIA model with anti-IL-17 antibody decreases the severity of inflammation and bone destruction (8). Further, local expression of IL-17 increases inflammation and synovial lining thickness (9) which we have shown to be associated with increased vascularity and monocyte recruitment (3, 6).

IL-27 is a heterodimeric cytokine produced by macrophages and dendritic cells, which belongs to the IL-12 cytokine family that includes IL-23 and IL-35 (10). IL-27 is composed of two subunits, EBI3 and p28, whose transcriptions are regulated independently. As such, dissociation of the two subunits’ expression may occur (11). Dendritic cells produce IL-27 when stimulated by pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMP) through Toll-like receptors (TLR)s (12). We have shown that macrophages from RA synovial fluid have significantly higher levels of IL-27 production compared with control cells; however, both groups of cells produced similar levels of IL-27 in the presence of the TLR2 ligation (3). Consistently, others have shown that IL-27 is expressed in RA synovium (13).

IL-27 mediates its proinflammatory effect by modulating the initial step of TH-1 cell differentiation through the induction of IL-12Rβ2 expression which can lead to IFN-γ production (14, 15). In agreement with these results, IL-27R-/- mice demonstrated reduced inflammation in the proteoglycan induced arthritis model by downregulating IFN-γ producing T cells (16). In contrast, IL-27 can also suppress inflammation by inhibiting murine TH-17 differentiation mediated by IL-6 and TGF-β. It was shown that the absence of IL-27 increased the severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) by promoting T cell proliferation and TH-17 cell differentiation (17, 18). Further, EAE in IL-27Rα-/- mice was ameliorated by employing antibody against IL-17 (17). The suppressive effect of IL-27 was distinct from that of IFN-γ since EAE induced in double knockouts of IFN-γ and IL-27Rα were more severe than in each single knockout alone. It was further shown that IL-27 is a potent suppressor of TH-17 cell development in a STAT1 dependent and IFN-γ independent way (17, 18). Others have shown that the anti-inflammatory properties of IL-27 may also be due to induction of IL-10 by CD4+ cells through a STAT1 and STAT3 dependent pathway (19).

Experiments were performed to examine the mechanism by which IL-27 affects the pathogenesis of CIA. Our results demonstrate that two of the cytokines promoting TH-17 differentiation and down stream targets of IL-17 in macrophages and fibroblasts were significantly reduced in ankles adenovirally expressing IL-27 compared to the controls. Ectopic expression of IL-27 in the ankles downregulated CIA vascularization and monocyte migration into synovial tissue compared to the control group. Using RA memory T cells we demonstrated that while IL-27 treatment significantly reduced percent TH-17 cells it had no effect on TH-1 cells. These results suggest that inhibition of TH-17 polarization through IL-27 may be a useful RA treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of Ad-IL-27

Mouse IL-27 cDNA was obtained from p3×FLAG-IL-27 plasmid described previously by Matsui et. al. (20) and Ad-IL-27 was constructed by Welgen, Inc (Worcester, MA). Briefly, IL-27 cDNA was cloned into pCR-topo vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) employing PCR. Thereafter IL-27 cDNA were released with Bgl2, and ligated to pENT-CMV predigested with the same enzyme and the positive clones were screened by digesting with BamH1 and sequenced. The pENT-IL-27 cDNA was treated with LR Clonase II enzyme (Invitrogen) and ligated to a pAd-REP plasmid that contains the remaining adenovirus genome. The recombination products were transformed into E. coli cells and after overnight incubation, the positive clones were selected, and cosmid DNA were purified. The purified cosmid DNA (2 μg) was digested with Pac1 and then transfected into 293 cells with Lipofectamine 2000 according to manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The 293 cells were grown in DMEM. The adenovirus plaques were seen 7 days after transfection. Concentration of the Ad-IL-27 was 3×1010 PFU as determined by plaque assay. The Ad-control employed in this study is an empty pEntCMV shuttle vector, with no insert (adenovirus purchased from Welgen).

Transfection of Ad-IL-27 in 293 cells and detection of Ad-IL-27 in mouse ankles

293 cells were cultured in a 6 well plate to 50-75% confluence. The next day, cells were infected at 0, 5, 10, 25 MOI of Ad-IL-27. Following 48h incubation, conditioned media and cells were collected. The conditioned media was concentrated using 30 kD columns (VWR, Westchester, PA) and Ad-IL-27 was detected in the conditioned media and cell lysates by probing for Flag (1:3000 dilution) and equal loading was determined by actin (1:3000 dilution) or stained with Coomassie blue. Mice were either i.a. injected with 105, 106 or 107 PFU Ad-IL-27 (injected into both ankles) or control. PBS and ankles were harvested after 5 days. Ankles were then homogenized in a 50-ml conical centrifuge tube containing 1 ml of Complete Mini-protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) homogenization buffer. Ankle homogenization was completed on ice using a motorized homogenizer, followed by 30 seconds of sonication. Homogenates were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 minutes and filtered through a 0.45-μm pore-size Millipore filter (Millipore, Bedford, MA) (21-23). Ad-IL-27 expression was examined in ankle homogenates through Western blot probing of Flag (1:3000 dilution) and equal loading was examined by actin (1:3000 dilution).

Study protocol for CIA and Ad-IL-27 treatment

7-8 week old DBA/1J mice were immunized with collagen on days 0 and 21. Two mg/ml bovine collagen type II (Chondrex, Redmond, WA) was emulsified in equal volumes of Complete Freud's Adjuvant (CFA) (2 mg/ml of M. tuberculosis strain H37Ra; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA or Chondrex). The DBA/1J mice were immunized subcutaneously in the tail with 100 μl of emulsion. On day 21, mice were injected intradermally with 100 μl of collagen type II (2 mg/ml) emulsified in equal volumes of Incomplete Freud's Adjuvant. Ad-IL-27 (n=15, 107 PFU) or Ad-control (n=15, 107 PFU) was injected intraarticularly (i.a.) on day 23 post CIA induction. Mice were sacrificed on day 42 and ankles were harvested for protein and mRNA extraction as well as histological studies and serum was saved for laboratory tests.

Clinical assessments

Ankle circumferences were determined by measurement of two perpendicular diameters, including the latero-lateral diameter and the antero-posterior diameter, using a caliper (Lange Caliper; Cambridge Scientific Industries). Circumference was determined using the following formula: circumference = 2Bx(sqrt(a2 + b2/2)), where a and b represent the diameters. Ankle circumference evaluations were performed on days 21, 23, 26, 28, 30, 33, 35, 36 and 41.

Flow cytometry

RA peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by Histopaque gradient centrifugation and memory CD4+ T cells were isolated employing a negative selection kit (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. RA memory CD4+ T cells were cultured and treated with PMA (50 ng/ml) and ionomyocin (1 μg/ml) with or without IL-27 treatment (100 ng/ml) for 48h. Brefeldin A (10 μg/ml) was supplemented to the cells 18h prior to performing the flow. Cells were then stained anti-CD4 (RPA-T4, BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), anti-IL-17 (eBio64DEC17, eBioscience, San Diego, CA), anti-IFN-γ (4S.B3, BD Pharmingen) or isotype control antibodies. Percentage of TH-17 or TH-1 cells were identified as those that were CD4+IL-17+ or CD4+IFN-γ+ respectively.

Abs and immunohistochemistry

Mouse ankles were decalcified, formalin fixed, paraffin embedded and sectioned in the pathology core facility of Northwestern University. Inflammation, synovial lining and bone erosion (based on a 0–5 score) were determined using H&E-stained sections by a blinded observer (A.M.M.). Mouse ankles were immunoperoxidase-stained using Vector Elite ABC Kits (Vector Laboratories), with diaminobenzidine (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) as a chromogen by the pathology core facility of Northwestern University. Briefly, slides were deparaffinized in xylene for 15 min at room temperature, followed by rehydration by transfer through graded alcohols. Antigens were unmasked by incubating slides in Proteinase K digestion buffer (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) for 5 min at room temperature. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubation with 3% H2O2 for 5 min. Nonspecific binding of avidin and biotin was blocked using an avidin/biotin blocking kit (Dako). Nonspecific binding of antibodies to the tissues was blocked by pretreatment of tissues with Protein block (Dako). Tissues were incubated with GR1 (1:200 dilution; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO), MAC 387 [(1:200 dilution; Serotec together with animal research kit (ARK; Dako)], Von willebrand factor (1:1000 dilution; Dako) or control IgG antibody (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). Slides were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin and treated with lithium carbonate for bluing. Neutrophil and macrophage staining were scored on a 0-5 scale. Vascularity was quantified as number of blood vessels per 5 random high power fields (HPF)s (magnification x10)(24). The data were pooled, and the mean ± SEM was calculated in each data group. Each slide was evaluated by a blinded observer (A.M.M.) (22, 23, 25, 26).

Quantification of proinflammatory factors

Mouse ankle and/or serum IL-17, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, CXCL1, CXCL5, CCL20 and CCL2 was quantified by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The sensitivity for the ELISAs performed to quantify mouse IL-17, IL-1β, IL-6, and CXCL1/5 is 7.8 pg/ml whereas for TNF-α and CCL20 it is 15.6 pg/ml. The expression level of each factor was normalized to the ankle protein concentration and shown as pg/mg and serum levels are shown as pg/ml.

Quantification of hemoglobin in mice ankles

Employing methemoglobin, serial dilutions were prepared to generate a standard curve from 70 to 1.1 g/dl (4, 27, 28). Fifty μl of homogenized mouse ankles or standard were added to a 96-well plate in duplicate and 50 μl tetramethylbenzidine was added to each sample. The plate was allowed to develop at room temperature for 15–20 min with gentle shaking, and the reaction was terminated with 150 μl 2 N H2SO4 for 3–5 min. Absorbance was read with an ELISA plate reader at 450 nm. To calculate hemoglobin concentrations in the mouse ankles, the values (g/dl) were normalized to the weights of the ankles (mg/ml) (4, 27, 28).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using two-tailed Student t tests for paired and unpaired samples. Values of p < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Expression of Ad-IL-27 in transfected 293 cells and in mouse ankles

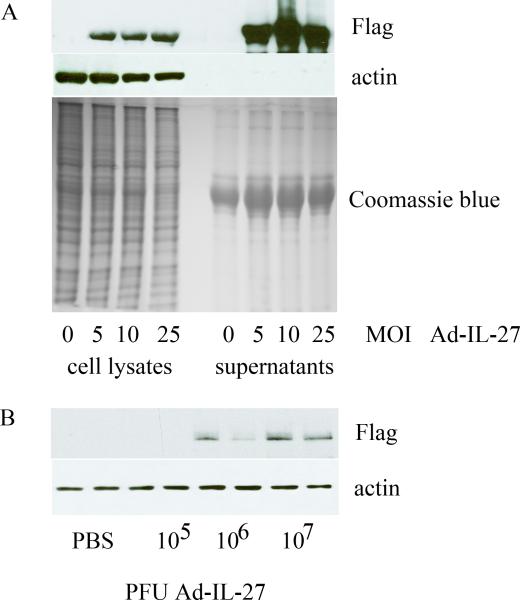

To verify that Ad-IL-27 was capable of expressing IL-27, 293 cells were transfected with 0, 5, 10, and 25 MOI of Ad-IL-27. Following a 48h incubation, protein expression was determined by Western blotting of both cell lysates and conditioned media. Using anti-Flag antibody we were able to detect Ad-IL-27 construct at 5, 10 and 25 MOI from both 293 cell lysates and conditioned media (Figure 1A). To validate the expression of IL-27 in vivo, mouse ankles were bilaterally injected with 105, 106, or 107 PFU of Ad-IL-27 or phosphaste-buffered saline (PBS) control. After 5 days, ankles were homogenized and Ad-IL-27 construct was detected employing anti-Flag antibody in Western blot analysis. Ad-IL-27 construct was detectable only in ankles receiving i.a. injection of 106 or 107 PFU Ad-IL-27, and not in 105 PFU injection or control mice (Figure 1B). Since both mouse ankles receiving 107 PFU Ad-IL-27 injections strongly expressed IL-27 compared to that of 106, the dose of 107 PFU Ad-IL-27 was selected for performing these experiments.

Figure 1. Western blot analysis of Ad-IL-27 construct.

A. Western blot analysis using anti-Flag, anti-actin or Coomassie blue protein staining of lysates and conditioned media obtained from 293 cells transfected with 0, 5, 10, and 25 MOI of Ad-IL-27. B. Western blot analysis using anti-Flag or anti-actin antibody on homogenates of mouse ankles injected with control (PBS) or 105, 106, or 107 PFU Ad-IL-27.

Effect of local IL-27 expression in CIA

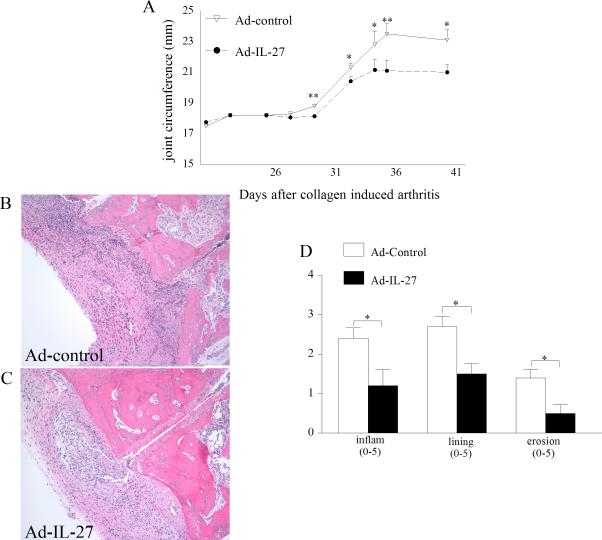

To determine the effect of IL-27 administration into the arthritic joint, Ad-IL-27 or Ad-control (107 PFU) was injected i.a. into DBA/1J mouse ankles 23 days post CIA induction. In the Ad-control injected mice, disease activity determined by ankle circumference began on day 30 and progressed through day 36, plateauing thereafter until the termination of the experiments on day 42 (Figure 2A). Mice treated with Ad-IL-27 demonstrated significantly reduced joint circumference compared with control animals (p<0.05 and p<0.01). Next, histological examination of the joints was performed to determine the effect of treatment on inflammation and joint destruction. Histological analysis of ankles from day 42 confirmed that Ad-IL-27 treatment resulted in significantly less inflammation (50% decrease), reduction in synovial lining thickness (45% decrease) and bone erosion (65% decrease) compared to the control group (Figure 2B-D). These results suggest that local expression of IL-27 can reduce CIA joint inflammation, synovial lining and bone destruction.

Figure 2. Local expression of IL-27 ameliorates CIA pathology.

A. Changes in joint circumference B. and C. H&E staining of CIA ankle with Ad-control and Ad-IL-27 injections (original magnification × 200). D. Effect of local expression of IL-27 on inflammation, lining thickness, and bone erosion. Values are mean ± SE, with n=10. * indicates p<0.05 and ** denotes p<0.01.

Effect of Ad-IL-27 treatment on proinflammatory factors expression in CIA ankles

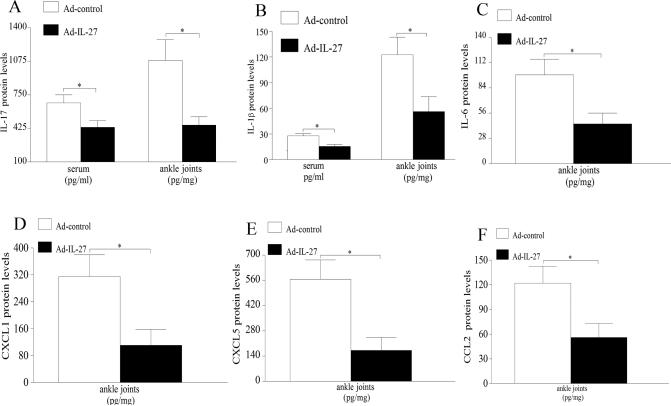

IL-27 is known to suppress inflammation by inhibiting TH-17 differentiation, therefore IL-17 expression levels were determined in serum and ankles of CIA mice receiving Ad-IL-27 or Ad-control. Our results demonstrate that IL-17 expression was significantly lowered in sera and ankle homogenates (35% and 55% respectively) from Ad-IL-27 treated animals compared to the control group (Figure 3A). Interestingly, we demonstrate that two of the cytokines that drive TH-17 differentiation, namely IL-1β and IL-6, were significantly reduced (55%) in mouse ankles and, additionally, levels of IL-1β were also decreased in sera (45%) of CIA mice that locally express IL-27 compared to the control treatment (Figure 3B-C). We have shown that CXCL1/5 and CCL2 are neutrophil and monocyte chemokines that are induced by IL-17 in RA ST fibroblasts and macrophages as well as in an IL-17-induced arthritis model (unpublished data and results published in (6)). In this study we demonstrate that ectopic expression of IL-27 significantly decreases joint CXCL1 (65%), CXCL5 (70%) and CCL2 (55%) levels compared to Ad-control treatment in CIA (Figure 3D-F). These results suggest that local expression of IL-27 could suppress TH-17 polarization as well as IL-17 downstream target genes.

Figure 3. Forced expression of IL-27 reduces joint IL-17 levels as well as proinflammatory factors.

Changes in IL-17 (A) or IL-1β (B) expression in sera and ankle homogenates from CIA mice treated with Ad-control or Ad-IL-27 were determined by ELISA. Levels of IL-6 (C) CXCL1 (D), CXCL5 (E) or CCL2 (F) expression in ankle homogenates from both treatment groups were quantified by ELISA. Values are mean ± SE, with n=9-10. * indicates p<0.05.

Treatment with IL-27 significantly reduces RA TH-17 cells without effecting TH-1 cells

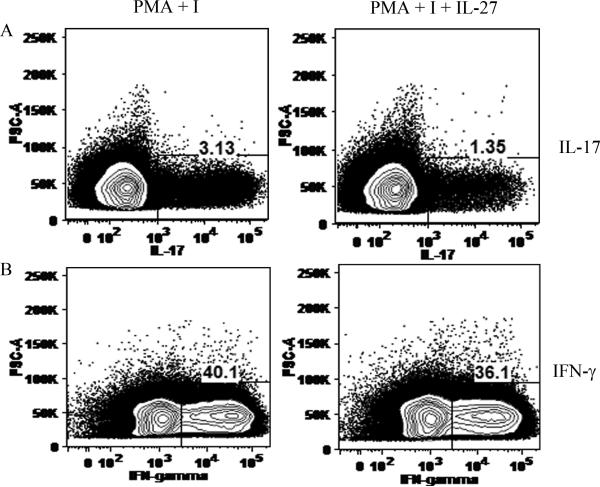

Since splenocytes and T cells are difficult to transfect due to low expression of adenovirus receptor, in order to demonstrate that IL-27 can directly reduce CD4+ IL-17+ cells, RA peripheral blood memory T cells were isolated by negative selection and were treated with PMA and ionomyosin with or without IL-27. Results from these experiments demonstrate that while IL-27 treatment significantly reduced TH-17 cells from 3 to 1 %, it had no effect on the TH-1 cell population (Figs. 4A-B). Consistently, when conditioned media IL-17 levels were quantified by ELISA (after 48 and 72h), cells treated with IL-27 had lower secretion of IL-17 compared to the control treatment group (data not shown).

Figure 4. IL-27 treatment reduces percentage of TH-17 cells but not TH-1 cells in RA peripheral blood.

Percentage of CD4+ IL-17+ (A) or CD4+ IFN-γ+ (B) cells are quantified in RA peripheral blood memory CD4+ T cells treated with PMA (50 ng/ml) plus ionomycin (I, 1μg/ml) only or PMA and I plus IL-27 (100 ng/ml) for 48h. Brefeldin A (10 μg/ml) was supplemented to the cells 18h prior to performing the flow cytometry. Results demonstrate that IL-27 treatment reduces TH-17 cells without affecting the TH-1 cells.

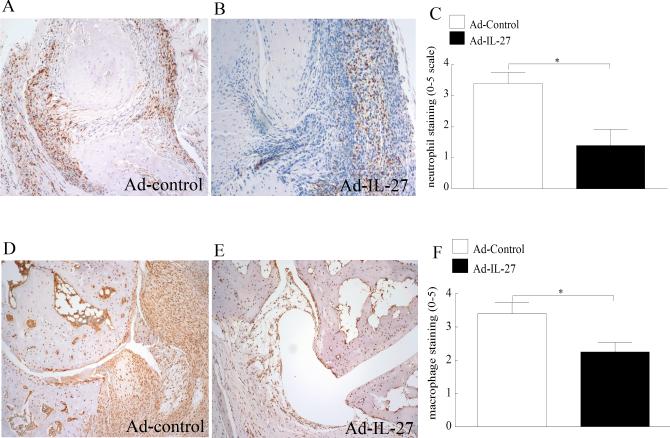

Effect of Ad-IL-27 treatment on leukocyte recruitment into CIA joint

We have shown thus far that local expression of IL-27 in CIA ankles significantly reduces inflammation as well as TH-17 polarizing cytokines and IL-17 induced downstream factors. Next, the effect of Ad-IL-27 on leukocyte recruitment into the inflamed CIA ankle joints was examined. In agreement with the clinical data, local expression of IL-27 greatly suppressed CIA neutrophil (60%) (Figure 5A-C) and monocyte (35%) ingression (Figure 5D-F) compared to the control group. Our results suggest that reduction of joint IL-17 levels can downregulate trafficking of neutrophils and monocytes into the CIA ankle.

Figure 5. Local expression of IL-27 downregulated CIA mediated neutrophil and monocyte ingression.

CIA ST harvested from Ad-control or Ad-IL-27 injected ankles on day 42 was immunostained with GR1 (neutrophil marker) (A-B) or MAC 387 (macrophage marker) (D-E) (original magnification × 200). Quantification of neutrophil (C) and macrophage (F) staining from CIA ankles harvested on day 42. Values are mean ± SE, with n=10.* indicates p<0.05.

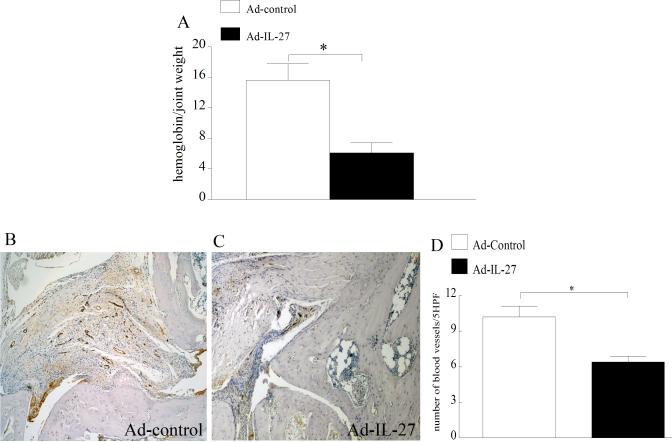

Effect of Ad-IL-27 treatment on CIA vascularization

Since angiogenesis is critical for leukocyte ingress, the effect of local IL-27 expression on CIA blood vessel formation was studied. CIA vascularization was quantified by measuring ankle hemoglobin levels and blood vessel staining. Ad-IL-27 treated CIA mice had markedly lower hemoglobin levels compared to the control group (Figure 6A). Consistently, there were fewer blood vessels in the CIA ankles that locally expressed IL-27 (40%) compared to control mice (Figure 6B-D). Our results suggest that IL-27 treatment inhibits IL-17-mediated angiogenesis in CIA.

Figure 6. Reduced vascularization was detected in CIA ankles locally expressing IL-27.

A. Quantified hemoglobin levels in CIA ankles harvested from different treatment groups on day 42 and results are demonstrated as hemoglobin (g/dl)/ joint weight (mg/ml). CIA ST harvested from Ad-control (B) or Ad-IL-27 (C) injected ankles on day 42 was immunostained with Von willebrand factor (endothelial marker) (original magnification × 200). D. Vascularization was quantified as number of blood vessels per 5 random HPF (magnification × 10) in each CIA ankle harvested on day 42. Values are mean ± SE, with n=10.* indicates p<0.05.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show that local expression of IL-27 in CIA ankles ameliorates joint inflammation and bone destruction. We further demonstrate that IL-27 modulates arthritis through reducing two important TH-17 polarizing cytokines as well as IL-17 activated factors in the CIA joint. In RA peripheral blood, IL-27 treatment directly reduces percent TH-17 cells, however, TH-1 cells were unaffected. Consequently, local expression of IL-27 in CIA ankles suppresses IL-17 mediated neutrophil and monocyte trafficking as well as vascularization. These results suggest that IL-27 can inhibit IL-17 induced acute (neutrophil migration) and chronic (monocyte recruitment) inflammation by affecting leukocyte ingress, controlled in part by the reduction in angiogenesis.

Early neutralization of IL-17 using an IL-17R IgG Fc fusion protein in CIA suppresses the onset of the disease (29). Treatment of CIA after disease onset using anti-IL-17 antibody decreases the severity of inflammation and bone destruction in CIA (8). These studies demonstrate that IL-17 plays an important role in the initiation and progression of CIA. Hence, we asked whether inhibition of TH-17 cell differentiation could reduce joint inflammation in CIA. The impact of local expression of IL-27 on TH-17 cells was observed both systemically and in the ankle joints as IL-17 levels in the sera and ankle homogenates were markedly decreased compared to the control group. Experiments were performed in RA peripheral blood in order to demonstrate that IL-27 treatment could directly inhibit TH-17 differentiation and that reduction in IL-17 levels was distinct from IFN-γ mediated TH-17 suppression. Consistent with previous findings (17, 18) we show that, TH-17 cell differentiation was suppressed 3 fold while TH-1 cell polarization was unaffected by IL-27 treatment in RA peripheral blood.

We found that local expression of IL-27 could alleviate clinical signs of CIA. Consistently, histological analysis demonstrates reduced inflammation, synovial lining thickness and bone erosion which may be due to suppressed joint IL-17 levels. It has been shown that IL-17 is involved in bone degradation through elevating expression of RANKL in CIA ankles (30) as well as synergizing with TNF-α and IL-6 in this process (31, 32).

TGF-β, IL-6, IL-1β and IL-21 drive the differentiation of TH-17 cells (33-35). However, some variation between humans and mice has been described. Levels of IL-1β and IL-6 but not TNF-α were markedly reduced in CIA mouse ankles locally expressing IL-27 compared to control group. Others have shown that in IL-1Ra-/- mice, elevated levels of IL-1β are responsible for an increase in the number TH-17 cells (36). In CIA, IL-6 is essential for TH-17 differentiation since anti-IL-6R antibody markedly suppresses induction of TH-17 cells and arthritis development (37). Consistent with our data, a previous study demonstrated that systemic administration of recombinant IL-27 could reduce serum IL-6 levels (13). Interestingly in CIA synoviocytes, neutralization of IL-1β and IL-6 significantly reduces IL-17 mediated TLR2, 4 and 9 expression (38). The results from our lab and others suggest that IL-1β and IL-6 are two of the cytokines that play an important role in CIA TH-17 differentiation. Therefore IL-27 can suppress polarization of TH-17 cells by modulating joint IL-1β and IL-6 levels.

Our unpublished studies demonstrate that IL-17 can induce CXCL1 expression from RA ST fibroblasts, macrophages and human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVECs). CXCL5 is also produced from IL-17 activated RA ST fibroblasts and macrophages (unpublished data). Previous studies have shown that neutrophil migration mediated by IL-17 intraarticular injection is dependent on CXCL1 and CXCL5, suggesting that both neutrophil chemokines are produced by cells in the ankle joints and play an essential role in IL-17 mediated neutrophil ingress (39). Neutrophil chemotaxis caused by conditioned media from IL-17 stimulated gastric epithelial cells was inhibited by neutralizing antibodies to IL-8, suggesting that in human cells IL-8 is responsible for IL-17 induced neutrophil trafficking (40). Similar to IL-8, CXCL1 and CXCL5 bind to CXCR2 and therefore may induce neutrophil migration through activation of the same pathway. Collectively, the data suggest that reduction of IL-17 by Ad-IL-27 suppresses neutrophil migration through modulating CXCL1 and CXCL5 in CIA ankle joints.

We have shown that IL-17 plays an important role in monocyte migration in RA, since neutralization of IL-17 in RA synovial fluid or its receptors on monocytes significantly reduces monocyte migration mediated by RA synovial fluid (5). Further, IL-17 promotes monocyte migration through activation of p38 MAPK (5). We also found that IL-17 activates CCL2 production from macrophages, RA ST fibroblasts and in experimental arthritis models (6). In addition to the direct effect of IL-17 on monocyte chemotaxis, we demonstrated that IL-17 mediated monocyte recruitment into the peritoneal cavity was due in part to CCL2 production (6). Despite the ability of IL-17 to induce the production of other monocyte chemokines such as CCL20 from cells present in the synovial lining (6), forced expression of IL-27 in CIA ankles did not affect the expression levels of this chemokine. Based on our previous studies, inhibition of monocyte recruitment into CIA ankles locally expressing IL-27 may be directly due to reduction of IL-17 levels or indirectly due to lower expression of IL-17-induced CCL2 or perhaps both mechanisms are essential for this process.

Angiogenesis is an early and critical event in the pathogenesis of RA which is triggered by the inflammatory process mediated by cytokines, chemokines and hypoxia (41). Previous studies demonstrate that angiogenesis is essential for CIA progression (42). In the current study we show that local expression of IL-27 significantly reduced synovial vascularity in CIA relative to control injected animals. This effect may be due to downregulation of joint IL-17 levels in ankles with forced IL-27 expression. We previously observed that IL-17, in concentrations present in the RA joint, induces endothelial migration through the PI3K/AKT1 pathway (4). Further we have demonstrated that IL-17 is angiogenic, determined by its ability to promote blood vessel growth in Matrigel plugs in vivo (4). However, reduced levels of proangiogenic chemokines CXCL1 and CXCL5 may also be responsible for the decreased vascularity in the Ad-IL-27 treatment group compared to controls (43). Given that angiogenesis promotes ingress of leukocytes, reduction in new blood vessel formation can affect neutrophil and monocyte trafficking.

In summary, local expression of IL-27 in CIA results in reduced disease severity quantified by joint swelling, synovial lining thickness, bone erosion, and leukocyte migration. In CIA, Ad-IL-27 treatment leads to reduced IL-1β and IL-6 production resulting in a depressed TH-17 response characterized by decreased joint IL-17 levels. This leads to decreased synovial production of neutrophil and monocyte chemokines CXCL1, CXCL5, and CCL2, ultimately resulting in fewer infiltrating leukocytes and lessened blood vessel formation.

Acknowledgments

1This work was supported by awards from Arthritis National Research Foundation, the National Institutes of Health AR056099, and grant from Within Our Reach from The American College of Rheumatology as well as funding provided by Department of Defense.

Footnotes

Study conception and design. Shahrara, Pickens.

Acquisition of data. Pickens, Volin, Mandelin, Chamberlain, Agrawal, Shahrara.

Analysis and interpretation of data. Chamberlain, Pickens, Volin, Matsui, Yoshimoto and Shahrara.

Providing reagents. Matsui and Yoshimoto

REFERENCES

- 1.Stamp LK, James MJ, Cleland LG. Interleukin-17: the missing link between T-cell accumulation and effector cell actions in rheumatoid arthritis? Immunol Cell Biol. 2004;82(1):1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2004.01212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lubberts E, Koenders MI, van den Berg WB. The role of T-cell interleukin-17 in conducting destructive arthritis: lessons from animal models. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7(1):29–37. doi: 10.1186/ar1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shahrara S, Huang Q, Mandelin AM, 2nd, Pope RM. TH-17 cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(4):R93. doi: 10.1186/ar2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pickens SR, Volin MV, Mandelin AM, 2nd, Kolls JK, Pope RM, Shahrara S. IL-17 contributes to angiogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol. 184(6):3233–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shahrara S, Pickens SR, Dorfleutner A, Pope RM. IL-17 induces monocyte migration in rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol. 2009;182(6):3884–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shahrara S, Pickens SR, Mandelin AM, 2nd, Karpus WJ, Huang Q, Kolls JK, et al. IL-17-Mediated Monocyte Migration Occurs Partially through CC Chemokine Ligand 2/Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 Induction. J Immunol. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901942. Page numbers. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakae S, Nambu A, Sudo K, Iwakura Y. Suppression of immune induction of collagen-induced arthritis in IL-17-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2003;171(11):6173–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lubberts E, Koenders MI, Oppers-Walgreen B, van den Bersselaar L, Coenen-de Roo CJ, Joosten LA, et al. Treatment with a neutralizing anti-murine interleukin-17 antibody after the onset of collagen-induced arthritis reduces joint inflammation, cartilage destruction, and bone erosion. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(2):650–9. doi: 10.1002/art.20001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koenders MI, Lubberts E, van de Loo FA, Oppers-Walgreen B, van den Bersselaar L, Helsen MM, et al. Interleukin-17 acts independently of TNF-alpha under arthritic conditions. J Immunol. 2006;176(10):6262–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.6262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pflanz S, Timans JC, Cheung J, Rosales R, Kanzler H, Gilbert J, et al. IL-27, a heterodimeric cytokine composed of EBI3 and p28 protein, induces proliferation of naive CD4(+) T cells. Immunity. 2002;16(6):779–90. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00324-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li J, Gran B, Zhang GX, Rostami A, Kamoun M. IL-27 subunits and its receptor (WSX-1) mRNAs are markedly up-regulated in inflammatory cells in the CNS during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neurol Sci. 2005;232(1-2):3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshida H, Nakaya M, Miyazaki Y. Interleukin 27: a double-edged sword for offense and defense. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86(6):1295–303. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0609445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niedbala W, Cai B, Wei X, Patakas A, Leung BP, McInnes IB, et al. Interleukin 27 attenuates collagen-induced arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2008;67(10):1474–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.083360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshida H, Hamano S, Senaldi G, Covey T, Faggioni R, Mu S, et al. WSX-1 is required for the initiation of Th1 responses and resistance to L. major infection. Immunity. 2001;15(4):569–78. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00206-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Q, Ghilardi N, Wang H, Baker T, Xie MH, Gurney A, et al. Development of Th1-type immune responses requires the type I cytokine receptor TCCR. Nature. 2000;407(6806):916–20. doi: 10.1038/35038103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao Y, Doodes PD, Glant TT, Finnegan A. IL-27 induces a Th1 immune response and susceptibility to experimental arthritis. J Immunol. 2008;180(2):922–30. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Batten M, Li J, Yi S, Kljavin NM, Danilenko DM, Lucas S, et al. Interleukin 27 limits autoimmune encephalomyelitis by suppressing the development of interleukin 17-producing T cells. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(9):929–36. doi: 10.1038/ni1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stumhofer JS, Laurence A, Wilson EH, Huang E, Tato CM, Johnson LM, et al. Interleukin 27 negatively regulates the development of interleukin 17-producing T helper cells during chronic inflammation of the central nervous system. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(9):937–45. doi: 10.1038/ni1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stumhofer JS, Silver JS, Laurence A, Porrett PM, Harris TH, Turka LA, et al. Interleukins 27 and 6 induce STAT3-mediated T cell production of interleukin 10. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(12):1363–71. doi: 10.1038/ni1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsui M, Moriya O, Belladonna ML, Kamiya S, Lemonnier FA, Yoshimoto T, et al. Adjuvant activities of novel cytokines, interleukin-23 (IL-23) and IL-27, for induction of hepatitis C virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in HLA-A*0201 transgenic mice. J Virol. 2004;78(17):9093–104. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9093-9104.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shahrara S, Amin MA, Woods JM, Haines GK, Koch AE. Chemokine receptor expression and in vivo signaling pathways in the joints of rats with adjuvant-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(12):3568–83. doi: 10.1002/art.11344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shahrara S, Proudfoot AE, Woods JM, Ruth JH, Amin MA, Park CC, et al. Amelioration of rat adjuvant-induced arthritis by Met-RANTES. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(6):1907–19. doi: 10.1002/art.21033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shahrara S, Proudfoot AE, Park CC, Volin MV, Haines GK, Woods JM, et al. Inhibition of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 ameliorates rat adjuvant-induced arthritis. J Immunol. 2008;180(5):3447–56. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kennedy A, Ng CT, Biniecka M, Saber T, Taylor C, O'Sullivan J, et al. Angiogenesis and blood vessel stability in inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 62(3):711–21. doi: 10.1002/art.27287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruth JH, Volin MV, Haines GK, III, Woodruff DC, Katschke KJ, Jr., Woods JM, et al. Fractalkine, a novel chemokine in rheumatoid arthritis and in rat adjuvant-induced arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2001;44:1568–1581. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200107)44:7<1568::AID-ART280>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koch AE, Nickoloff BJ, Holgersson J, Seed B, Haines GK, Burrows JC, et al. 4A11, a monoclonal antibody recognizing a novel antigen expressed on aberrant vascular endothelium. Upregulation in an in vivo model of contact dermatitis. American Journal of Pathology. 1994;144(2):244–259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haas CS, Amin MA, Ruth JH, Allen BL, Ahmed S, Pakozdi A, et al. In vivo inhibition of angiogenesis by interleukin-13 gene therapy in a rat model of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(8):2535–48. doi: 10.1002/art.22823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park CC, Morel JC, Amin MA, Connors MA, Harlow LA, Koch AE. Evidence of IL-18 as a novel angiogenic mediator. Journal of Immunology. 2001;167(3):1644–1653. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bush KA, Farmer KM, Walker JS, Kirkham BW. Reduction of joint inflammation and bone erosion in rat adjuvant arthritis by treatment with interleukin-17 receptor IgG1 Fc fusion protein. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(3):802–5. doi: 10.1002/art.10173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lubberts E, van den Bersselaar L, Oppers-Walgreen B, Schwarzenberger P, Coenen-de Roo CJ, Kolls JK, et al. IL-17 promotes bone erosion in murine collagen-induced arthritis through loss of the receptor activator of NF-kappa B ligand/osteoprotegerin balance. J Immunol. 2003;170(5):2655–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kotake S, Sato K, Kim KJ, Takahashi N, Udagawa N, Nakamura I, et al. Interleukin-6 and soluble interleukin-6 receptors in the synovial fluids from rheumatoid arthritis patients are responsible for osteoclast-like cell formation. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11(1):88–95. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650110113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romas E, Gillespie MT, Martin TJ. Involvement of receptor activator of NFkappaB ligand and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in bone destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. Bone. 2002;30(2):340–6. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00682-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manel N, Unutmaz D, Littman DR. The differentiation of human T(H)-17 cells requires transforming growth factor-beta and induction of the nuclear receptor RORgammat. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(6):641–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Volpe E, Servant N, Zollinger R, Bogiatzi SI, Hupe P, Barillot E, et al. A critical function for transforming growth factor-beta, interleukin 23 and proinflammatory cytokines in driving and modulating human T(H)-17 responses. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(6):650–7. doi: 10.1038/ni.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Annunziato F, Cosmi L, Liotta F, Maggi E, Romagnani S. Type 17 T helper cells-origins, features and possible roles in rheumatic disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2009;5(6):325–31. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koenders MI, Devesa I, Marijnissen RJ, Abdollahi-Roodsaz S, Boots AM, Walgreen B, et al. Interleukin-1 drives pathogenic Th17 cells during spontaneous arthritis in interleukin-1 receptor antagonist-deficient mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(11):3461–70. doi: 10.1002/art.23957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fujimoto M, Serada S, Mihara M, Uchiyama Y, Yoshida H, Koike N, et al. Interleukin-6 blockade suppresses autoimmune arthritis in mice by the inhibition of inflammatory Th17 responses. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(12):3710–9. doi: 10.1002/art.24126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee JH, Cho ML, Kim JI, Moon YM, Oh HJ, Kim GT, et al. Interleukin 17 (IL-17) increases the expression of Toll-like receptor-2, 4, and 9 by increasing IL-1beta and IL-6 production in autoimmune arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(4):684–92. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lemos HP, Grespan R, Vieira SM, Cunha TM, Verri WA, Jr., Fernandes KS, et al. Prostaglandin mediates IL-23/IL-17-induced neutrophil migration in inflammation by inhibiting IL-12 and IFNgamma production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(14):5954–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812782106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luzza F, Parrello T, Monteleone G, Sebkova L, Romano M, Zarrilli R, et al. Up-regulation of IL-17 is associated with bioactive IL-8 expression in Helicobacter pylori-infected human gastric mucosa. J Immunol. 2000;165(9):5332–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szekanecz Z, Koch AE. Angiogenesis and its targeting in rheumatoid arthritis. Vascul Pharmacol. 2009;51(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mould AW, Tonks ID, Cahill MM, Pettit AR, Thomas R, Hayward NK, et al. Vegfb gene knockout mice display reduced pathology and synovial angiogenesis in both antigen-induced and collagen-induced models of arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(9):2660–9. doi: 10.1002/art.11232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Numasaki M, Watanabe M, Suzuki T, Takahashi H, Nakamura A, McAllister F, et al. IL-17 enhances the net angiogenic activity and in vivo growth of human non-small cell lung cancer in SCID mice through promoting CXCR-2-dependent angiogenesis. J Immunol. 2005;175(9):6177–89. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]