Abstract

Incapacitated/drug-alcohol facilitated sexual assault (IS/DAFS) is rapidly gaining recognition as a distinct form of assault with unique public health implications. This study reports the prevalence, case characteristics, and associated health risks of IS/DAFS using a large, nationally representative sample of 1,763 adolescent girls. Results indicate that 11.8% of girls experienced at least one form of sexual assault; 2.1% of the total sample experienced IS/DAFS. Thus IS/DAFS accounted for 18% of all reported sexual assaults, with a prevalence of 4.0% among girls 15 to 17 years of age and 0.7% among girls 12 to 14 years of age. Girls with a history of IS/DAFS were significantly more likely than girls with other sexual assault histories to report past-year substance abuse but not significantly more likely than girls with other sexual assault histories to report past-year depression or posttraumatic stress disorder.

Adolescence is a high-risk period for sexual assault; about one third of rape victims in the United States report rape during this developmental stage. Adolescent sexual assault is associated with increased risk for a range of mental health problems. Longitudinal findings indicate that adolescent sexual assault is associated with increased risk of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depression (MDE), and substance use/abuse disorders (Boney-McCoy & Finkelhor, 1996; Kilpatrick, Ruggerio et al., 2003). Whereas most studies have examined sexual assault broadly defined, few have specifically addressed incapacitated or drug/alcohol-facilitated sexual assault (IS/DAFS). IS/DAFS is defined as completed sexual assault by means of the victim’s self-induced intoxication or by means of the perpetrator’s deliberate intoxication of the victim. The Campus Sexual Assault (CSA) study sampled more than 5,000 undergraduate women at two large universities regarding sexual assault experiences prior to entering college (Krebs, Lindquist, Warner, Fisher, & Martin, 2007). In this study, 7% of women reported IS/DAFS in adolescence. Given that the CSA sampled only a small subset of college women, these prevalence data are in need of replication with a sample representative of adolescents in the United States.

Whereas there is a paucity of relevant data on youth, research with adult rape victims has begun to distinguish potential differences in rape characteristics and health correlates between forcible rape and IS/DAFS. For example, among adult women, forcible rape has been associated with age and history of child sexual abuse, whereas incapacitated rape has been associated with adolescent alcohol and drug use (Testa, Livingston, VanZile-Tamsen, & Frone, 2003). However, implications of these findings for adolescent victims are unclear, and little is known about whether mental health correlates differ as a function of type of assault. This study reports prevalence, health correlates, and case characteristics of IS/DAFS using a large, nationally representative sample of adolescent girls.

METHOD

Data collection procedures were similar to those used in the 1995 National Survey of Adolescents (NSA; see Kilpatrick et al., 2000; Kilpatrick, Saunders, & Smith, 2003). Participants were selected using a multistage, stratified, random-digit dial procedure within each region of the country. During recruitment 6,694 house-holds were contacted, which resulted in both a completed parent interview and identification of at least one eligible child. A child was considered eligible if he or she (a) resided in a household with a telephone, (b) spoke either English, and (c) was between 12 and 17 years of age. Of these 6,694 eligible households, parent and child interviews were completed in 3,614 cases, resulting in a 54% participation rate. This included 2,459 adolescents in the national probability household sample and a probability oversample of 1,155 urbandwelling adolescents (i.e., adolescents from households in areas designated as central cities by the U.S. Census). Parental consent and adolescent assent were obtained verbally prior to conducting interviews.

Because adolescents were oversampled in urban areas, cases were weighted to maximize representativeness of the sample to the U.S. adolescent population. A weight was created to restore the urban cases back to their true proportion of the urban/suburban/rural variable, based on U.S. census estimates. Next, weights were created to adjust the weight of each case based on age and gender to closely approximate U.S. census estimates.

The IS/DAFS interview module was administered only to girls, resulting in a final sample size of 1,763 adolescent girls. This final sample consisted of girls between the ages of 12 and 17 years. Seventy percent were Caucasian, non-Hispanic; 14% were African American, non-Hispanic; 11% were Hispanic; 3% were Native American; and 2% were Asian.

Measures

Sexual assault module

Sexual assault was operationalized as an affirmative response to questions measuring forced (a) vaginal or anal penetration by an object, finger, or penis; (b) oral sex; (c) touching of the respondent’s breasts or genitalia; or (d) respondents’ touching of another person’s genitalia. Interview questions were virtually identical to those used in the 1995 NSA survey (see Kilpatrick et al., 2000).

IS/DAFS

We assessed IS/DAFS incidents in two ways. First, girls who endorsed one or more items within the sexual assault module were asked a series of follow-up questions that included assessment of the involvement of drugs or alcohol in the incident(s) (see Appendix A). Second, a separate module on IS/DAFS was included in the interview that asked specifically about IS/DAFS incidents (see Appendix B). Participants were classified as having experienced an incident of IS/DAFS if they reported an incident of sexual assault as part of the sexual assault screen or the IS/DAFS module that included either voluntary use or administration of drugs or alcohol that led to the respondent being passed out, unaware of what was happening, or unable to control the situation.

PTSD

Current (i.e., past year) PTSD was assessed using the PTSD module of the NSA survey (Kilpatrick, Resnick, Saunders, & Best, 1989), a structured diagnostic interview that assessed each Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed. [DSM-IV]; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) symptom and functional impairment with a yes/no response. Research on this measure has provided support for concurrent validity and several forms of reliability (e.g., temporal stability [κ = 0.45], internal consistency [α = 0.83]; Resnick, Kilpatrick, Dansky, Saunders, & Best, 1993).

MDE

MDE was assessed with the Depression Module of the NSA survey, a structured interview that targets MDE criteria using a yes/no response format for each DSM-IV symptom for the prior 12 months. Psychometric data support the internal consistency (α = .85; Kilpatrick et al., 2003) and convergent validity (Boscarino et al., 2004) of the Depression module. Boscarino et al. compared the depression module against the depression scale of the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (Derogatis, 2001), yielding a correlation coefficient of .52, sensitivity of 73%, and specificity of 87% in detection of MDE as classified by our instrument.

Alcohol abuse and nonexperimental drug use

Past-year alcohol abuse and nonexperimental drug use (i.e., illicit drugs, club drugs, nonmedical consumption of prescription drugs) were assessed separately via a series of inquiries about the frequency of use, age at onset, and presence and frequency of impairing or distressing experiences related to substance use occurring within the past 12 months (see Kilpatrick et al., 2000, for more detail). In addition to face validity, previous research supports the construct validity of this measure (Kilpatrick, Acierno, Resnick, Saunders, & Best, 1997).

Kilpatrick et al.’s (1997) operationalization of nonexperimental drug use was also employed in this study. For each drug assessed, adolescents who reported illicit drug use, club drug use, or nonmedical consumption of prescription drugs four or more times in the past year were designated as nonexperimental drug users. Kilpatrick et al. noted that this frequency of usage is consistent with that considered significant when using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (Robins, Heltzer, Cottler, & Golding, 1988) and is appropriate given potential physical and legal hazards associated with obtaining and using illicit substances.

Procedure

The structured telephone interview averaged about 43 min. The interview was administered in English by trained interviewers employed by an experienced survey research firm using a computer-assisted telephone interview system to aid this process by prompting interviewers with each question consecutively on a computer screen. Supervisors conducted random checks of data entry accuracy and interviewers’ adherence. The Institutional Review Board at the Medical University of South Carolina approved all procedures for this study.

RESULTS

A series of chi-square analyses revealed no significant differences in race/ethnicity between those with and without history of IS/DAFS. Girls reporting an IS/DAFS experience were significantly older than the mean age of the total sample (M = 16.0 vs. M = 14.5), F(1, 1750) = 28.22, p < .001, and significantly older than those reporting other forms of sexual assault (M = 16.0 vs. M = 15.2), F(1, 205) = 8.96, p < .01.

Some form of sexual assault was reported by 11.8% of adolescent girls. The prevalence of IS/DAFS in this sample was 2.1% of adolescent girls. Approximately 9.7% experienced non-IS/DAFS sexual assault. Thus, IS/DAFS accounted for 18% of all reported sexual assaults in this sample. A majority of those endorsing IS/DAFS (91.9%) reported incidents that included unwanted sexual penetration. Approximately 3.3% of the total sample experienced unwanted sexual penetration as part of at least one other sexual assault incident. With respect to IS/DAFS, 1.9% of girls experienced un wanted sexual penetration as part of at least one incident. Of those reporting other forms of sexual assault, 30.2% included sexual penetration. IS/DAFS was significantly more prevalent among older adolescents (15–17 years of age at 3.6% prevalence) than younger adolescents (12–14 years of age at 0.7% prevalence), with the modal age of the IS/DAFS victim being 17 years (M = 15.98, SD = 1.31), χ2(1, N = 1,743) = 17.62, p < .001.

Several of the aforementioned prevalence estimates may be translated into population figures based on 2005 U.S. Census data. Our findings suggest that approximately 3 million U.S. adolescent girls have experienced some form of sexual assault, with 525,000 of these girls reporting an experience of IS/DAFS and 2.4 million a non-IS/DAFS sexual assault. We also estimate that 815,400 U.S. adolescent girls experience penetration as part of their assault. Further, we estimate that approximately 483,000 adolescent girls will report penetration as part of at least one IS/DAFS incident. See Table 1 for further information on population estimates by age.

TABLE 1.

IS/DAFS Population Estimates by Age Based on 2000 Census

| Bureau Data | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | Population (2000 est.) |

IS/DAFS in Population |

| 12 | 1,988,614 | 0 |

| 13 | 1,956,842 | 21,525 |

| 14 | 1,972,671 | 15,781 |

| 15 | 1,954,277 | 33,223 |

| 16 | 1,926,439 | 52,014 |

| 17 | 1,954,732 | 123,148 |

Note: IS/DAFS = Incapacitated or drug/alcohol-facilitated sexual assault; estimates are based on census data from 2000 Census, not based on population estimates produced in 2005.

Analysis of case characteristics was conducted based on the “most recent/only” incident using weighted data only from girls who screened positive for at least one IS/DAFS experience (n = 37). A majority (67.7%) of the cases involved endorsements of being “too drunk to know what was happening” during the assault, whereas in nearly one half of the cases (48.3%) respondents stated that they were actually “passed out” because of alcohol or other drugs during the sexual assault. Most (80.3%) incidents were perpetrated by someone known to the victim. Perpetrators were adolescents in four of five cases involving known perpetrators.

A significant minority (34%) of the IS/DAFS incidents also involved the use of some degree of physical force. Thirty percent of the incidents were reported to have involved the victim experiencing some level of fear of injury or death (in comparison to 41.5% of victims of other forms of sexual assault reporting such fears). However, only 4.6% of the IS/DAFS incidents were reported to police or other appropriate authorities.

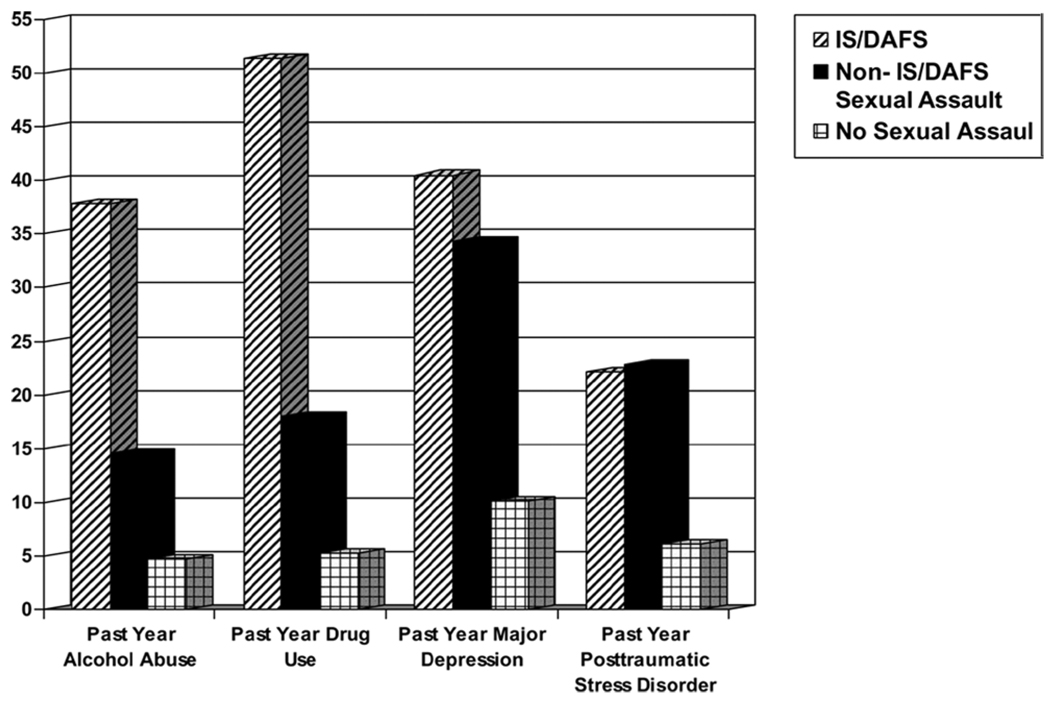

A series of chi-square analyses explored past year mental health outcomes. Girls were grouped according to their reported lifetime sexual assault history: (a) girls with a history of IS/DAFS, (b) girls with a sexual assault history that did not include IS/DAFS, and (c) girls with no sexual assault history. These groups were compared on the following past year mental health outcomes: (a) past-year alcohol abuse, (b) past-year nonexperimental illicit drug use, (c) past-year MDE, and (d) past-year PTSD. Girls with a history of IS/DAFS were more likely than girls without any sexual assault history to report alcohol abuse, χ2(1, N = 1,562) = 76.15, p < .001; drug use, χ2(1, N = 1,564) = 127.98, p < .001; MDE, χ2(1, N = 1,564) = 34.11, p < .001; and PTSD, χ2(1, N = 1,553) = 14.98, p < .001. Girls with a history of IS/DAFS were also more likely than girls with other sexual assault histories to report past-year alcohol abuse, χ2(1, N = 208) = 10.76, p <.001; and past-year nonexperimental (i.e., greater than four times) drug use, χ2(1, N = 208) = 16.05, p < .001. Girls with a history of IS/DAFS were comparable to girls with other sexual assault histories with regard to reporting past year MDE or PTSD (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of girls with (a) history of incapacitated/drug-alcohol facilitated sexual assault (is/dafs), (b) nonincapacitated/drug-alcohol facilitated sexual assault history (non-is/dafs), and (c) no sexual assault history, reporting past-year mental health problems (alcohol abuse, drug use, major depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to extend the literature on prevalence, case characteristics, and associated health risks of IS/DAFS from existing adult samples to a national sample of adolescent girls. IS/DAFS is a significant public health issue among adult women, and the current data suggest that IS/DAFS is a significant public health issue in adolescence. This finding is consistent with findings on alcohol use in this population that almost 30% of high school students report drinking initiation prior to age 13 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2003) and that the reported the median age for female adolescents’ onset of drinking is 14.4 years (Warren et al., 1997). These estimates are consistent with our findings that the prevalence of IS/DAFS increases noticeably for 15- to 17-year-olds (M age = 16) and that most victims identify a known adolescent perpetrator. The early age of drinking onset coupled with significant increases in IS/DAFS risk suggest that waiting until college to address these risks may be too late for some girls. Early intervention and psychoeducation efforts pertaining to these issues may be more beneficial when targeted toward girls in middle school/early high school.

Similar to findings with college and community samples, IS/DAFS was most likely to be perpetrated by someone known to the victim (e.g., Abbey, Clinton, McAuslan, Zawacki, & Buck, 2002). Although the results of this study suggest similar environs being common to adult versus adolescent IS/DAFS experiences, future research should examine more carefully locations conferring analogous risk for adolescent girls. Also consistent with evidence from adult samples, adolescent victims of IS/DAFS had a very low likelihood of reporting their sexual assault to law enforcement (4.6%). This rate is considerably lower than reporting rates for other types of sexual assault (R. F. Hanson, Resnick, Saunders, Kilpatrick, & Best, 1999) and is lower in comparison to IS/DAFS reporting rates among college women (7.0%) and adult community samples (10%; Kilpatrick, Resnick, Ruggiero, Conoscenti, & McCauley, 2007). It is possible that girls’ concerns about acknowledging their exposure to environments in which underage drinking is occurring may serve as an additional impediment to reporting IS/DAFS in this sample. However, this should be explicitly assessed in this population. Consideration should also be given to potential mechanisms to increase incentives for reporting in this population.

Girls with IS/DAFS experiences were significantly more likely than girls with no assault history to report a range of past-year mental health problems, including PTSD, MDE, alcohol abuse, and drug use. Further, consistent with research on adults, when compared with victims of other forms of sexual assault, IS/DAFS DAFS emerged as being associated with greater risk of past year alcohol abuse and illicit drug use (Testa et al., 2003). This substance use may, in turn, increase risk for revictimization and exposure to additional traumatic events (Gidycz, Coble, Latham, & Layman, 1993). More than half of girls reporting IS/DAFS experiences also reported past-year illicit drug use and more than one third met criteria for alcohol abuse. These figures are striking in comparison to victims of other forms of sexual assault as well as nonvictimized adolescents. Taken together, these findings highlight the necessity of concurrently assessing substance use and sexual assault history among at-risk adolescents. That IS/DAFS is a distinct correlate of substance use problems suggests that interventions that are successful in preventing adolescent alcohol and drug abuse may also have the potential to decrease risk for future IS/DAFS experiences and that intervention developers should consider incorporating psychoeducation on IS/DAFS into existing protocols.

A major strength of this study is the methodology, which included behaviorally specific questions designed to increase the likelihood of detection of sexual assault experiences. However, some adolescents may have been reluctant to disclose an assault, especially for IS/DAFS incidents where their own substance use might be revealed. Approximately 46% of the contacted households did not result in completed parent and child interviews, warranting caution in complete generalization to the entire population of U.S. adolescents. In addition, given the relatively low proportion of the total sample that experienced IS/DAFS (n = 37), information on assault case characteristics and mental health correlates may have limited generalizability and are in need of replication. Finally, this study is not able to address the issue of order of onset regarding mental health correlates and IS/DAFS given the cross-sectional nature of the data; thus no definitive statements pertaining to causality may be taken from these data.

Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice

This study is the first to extend the literature on IS/DAFS to an adolescent population. Longitudinal research would be helpful in determining whether adolescent victims of IS/DAFS are at risk for the same long-term consequences as adolescent victims of non-drug or alcohol involved sexual assaults. Although several sexual assault risk reduction programs have shown modest efficacy in reducing victimization risk among participants (for a review, see R. K. Hanson & Broom, 2005), these interventions have specifically and exclusively targeted women in college. To date, a limited literature exists on empirically supported sexual assault prevention programming geared toward adolescents, and existing programs do not include specific references to risk for IS/DAFS (for review see Lonsway, 1996). Therefore, perhaps most important, our study calls for the development and implementation of efficacious risk reduction interventions as well as an integration of information on IS/DAFS into existing substance use interventions targeting adolescents, specifically those adolescents at greatest risk for IS/DAFS victimization and associated misuse of substances.

APPENDIX A

Participants who endorsed involvement of alcohol or drugs were asked, “When this happened, did you [drink the alcohol, take the drugs] because you wanted to or did the person(s) who had sex with you deliberately try to [get you drunk, give you drugs] without your permission?” Respondents were then asked, “When this incident happened were you passed out from drinking or taking drugs?” followed by, “When this incident happened were you awake but too drunk or high to know what you were doing or control your behavior?”

APPENDIX B

This module was administered to all female respondents, regardless of responses to questions in the sexual assault module, and began with prefatory statements as follows:

There has been a lot of talk about the use of alcohol or drugs in social, dating, party, and sexual situations. Some young people say they have had sex in these situations when they didn’t want to because they were very high, intoxicated, or even passed out because of alcohol or drugs. We would like to ask you a few questions about experiences like this you might have had.

Interviewers then read, “Has anyone ever had sex with you when you didn’t want to after you drank so much alcohol that you were very high, drunk, or passed out? By having sex, we mean that a man or boy put his private sexual part in your private sexual part, your rear end, or your mouth?” This was followed by a second question: “Has anyone ever had sex with you when you didn’t want to after someone gave you or you had taken enough drugs to make you very high, intoxicated, or passed out?” Finally, participants were asked about whether they passed out as a result of substance use, were unaware of what was happening, or were unable to control the situation, as described above.

Footnotes

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Contributor Information

Jenna L. McCauley, National Crime Victims Center, Department of Psychiatry, Medical University of South Carolina

Lauren M. Conoscenti, National Center for PTSD, VA Boston Healthcare System

Kenneth J. Ruggiero, National Crime Victims Center, Department of Psychiatry Medical University of South Carolina

Heidi S. Resnick, National Crime Victims Center, Department of Psychiatry Medical University of South Carolina

Benjamin E. Saunders, National Crime Victims Center, Department of Psychiatry Medical University of South Carolina

Dean G. Kilpatrick, National Crime Victims Center, Department of Psychiatry Medical University of South Carolina

REFERENCES

- Abbey A, Clinton AM, McAuslan P, Zawacki T, Buck PO. Alcohol involved rapes: Are they more violent? Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2002;26:99–109. doi: 10.1111/1471-6402.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Boney-McCoy S, Finkelhor D. Is youth victimization related to trauma symptoms and depression after controlling for prior symptoms and family relationships? A longitudinal, prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:1406–1416. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscarino JA, Galea S, Adams RE, Ahern J, Resnick H, Vlahov D. Mental health service and medication use in New York City after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack. Psychiatric Services. 2004;55:274–283. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.3.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance: United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2003;53(SS-02):1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. Brief Symptom Inventory 18 (BSI-18) manual. Minnetonka, MN: NCS Assessments; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, Coble C, Latham L, Layman M. Sexual assault experience in adulthood and prior victimization experiences. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1993;17:151–168. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson RF, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG, Best CL. Factors related to the reporting of childhood rape. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999;23:559–569. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson RK, Broom I. The utility of cumulative meta-analysis: Application to programs for reducing sexual violence. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment. 2005;17:357–373. doi: 10.1177/107906320501700402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Best CL. A two year longitudinal analysis of the relationship between violent assault and alcohol and drug use in women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:834–847. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Saunders BE, Resnick HS, Best CL, Schnurr PP. Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence: Data from a national sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:19–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Ruggiero KJ, Conoscenti LM, McCauley J. Drug-facilitated, incapacitated, and forcible rape: A national study (Final report submitted to the National Institute of Justice) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Best CL. The National Women’s Study PTSD Module. Charleston: Medical University of South Carolina; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno RE, Saunders BE, Resnick HS, Best CL. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: Results from the National Survey of Adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:692–700. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Saunders BE, Smith DW. Youth victimization: Prevalence and implications. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs CP, Lindquist CH, Warner TD, Fisher BS, Martin SL. The campus sexual assault (CSA) study (Final report submitted to the National Institute of Justice) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lonsway KA. Preventing acquaintance rape through education: What do we know? Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1996;20:229–265. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Dansky BS, Saunders BE, Best CL. Prevalence of civilian trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a representative national sample of women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:984–991. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins L, Helzer J, Cottler L, Golding E. National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version Three Revised. St. Louis, MO: Washington University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Livingston JA, Vanzile-Tamsen C, Frone MR. The role of women’s substance use in vulnerability to forcible and incapacitated rape. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:756–764. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren CW, Kann L, Small ML, Stanelli JS, Collins JL, Kolbe LJ. Age of initiating selected health risk behaviors among high school students in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1997;21:225–231. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]