Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Despite the growing use of patient-reported outcomes, few studies directly compare health-related quality of life (HRQOL) across different pediatric chronic illnesses. Understanding the differential impact of specific illnesses on youth psychosocial functioning has treatment implications, especially for primary care providers. This study compared HRQOL across eight pediatric chronic conditions, including five understudied populations, and examined convergence between youth self-report and parent-proxy report.

STUDY DESIGN

Secondary data from 589 patients and their caregivers were collected across the following conditions: obesity, eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorder (EGID), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), epilepsy, type 1 diabetes, sickle cell disease (SCD), post-renal transplantation, and cystic fibrosis (CF). Youth and caregivers completed age-appropriate self-report and/or parent-proxy report generic HRQOL measures.

RESULTS

Youth diagnosed with EGID and obesity experienced lower HRQOL than other pediatric conditions by parent report. Caregivers reported lower HRQOL by proxy-report than youth self-reported across most subscales.

CONCLUSION

This study provides information regarding differences in HRQOL, especially youth with EGID and obesity, and highlights areas of concern for clinicians. Use of brief, easily administered, and reliable assessments of psychosocial functioning, such as HRQOL, may provide clinicians additional opportunities for intervention or services targeting improved HRQOL relative to the needs of each population.

Keywords: quality of life, parent-child agreement

INTRODUCTION

As the number of children living with a chronic illness in the United States has risen (1), and medical advances have improved treatment outcomes and increased survival rates (2), health-related quality of life (HRQOL) has emerged as an informative and widely accepted health outcome measure to assess the multidimensional impact of a chronic illness on children's overall well-being (3). A large body of literature currently exists examining HRQOL in individual disease groups and a number of generic and disease-specific measures are available (4). Assessment of HRQOL is especially important given recent recommendations for healthcare providers to focus greater attention on psychosocial domains of patients’ lives and patient-reported outcomes (5). However, the psychosocial factors that impact patient HRQOL are likely to vary across disease groups as a function of the unique demands (e.g., onset, treatment course, and prognosis (6)) each illness places on patients and their families. Furthermore, while a number of studies find that caregivers often report lower HRQOL for youth by proxy-report than youth by self-report (7-9), the generalizability of this finding across disease groups is less certain. Consequently, the need for better understanding of HRQOL across chronic conditions is increasingly important. This is particularly true for primary care providers who are faced with providing primary health care to youth with a wide range of chronic health conditions (10, 11) and who must understand the unique psychosocial impact that these conditions have on their individual patients and families within a broad, pediatric practice.

In recognition of this need, researchers have begun to compare HRQOL across various chronic illness groups (12-14). A recent study using an evidence-based measure of HRQOL reported significant differences between ten disease groups, indicating that HRQOL differed among chronic illnesses and between chronic illness and healthy control groups (13). Although this study provides valuable information regarding HRQOL across several chronic conditions, those conditions were generally highly researched populations such as cancer, obesity, diabetes, and rheumatologic disorders. Thus, additional research is needed, to extend the literature by examining HRQOL in understudied chronic conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGID), epilepsy, sickle cell disease, and post-renal transplantation and to confirm previous findings in populations such as obesity, type 1 diabetes, and cystic fibrosis. While an emerging body of literature exists examining HRQOL in individual understudied disease groups (e.g., (15, 16)), research describing how these youth are functioning relative to more widely studied disease groups remains needed. Combined with the extant literature, these additional data may offer providers valuable information regarding the HRQOL of patients across a wide array of chronic conditions, and provide a clearer picture of the general well-being of patients in their practice. Thus, the current study will (1) extend the current literature by comparing HRQOL across eight different pediatric chronic conditions, five of which represent understudied pediatric populations, and (2) examine convergence in self-reported and parent-proxy reported patient HRQOL across these conditions.

METHODS

Participants and Procedures

Secondary data from 589 patients and their caregivers were collected across eight descriptive studies in the following eight conditions: obesity, EGID, IBD, epilepsy, type 1 diabetes, sickle cell disease (SCD), post-renal transplantation, and cystic fibrosis (CF). For longitudinal studies, only the first time point of data collection was included. All participants were recruited during previously scheduled clinic/hospital visits or via telephone following clinic appointments. Informed consent/assent was obtained by research team members prior to completing assessments. Each study's procedures were approved by the hospitals’ Institutional Review Boards.

Measures

Family demographic data were obtained from separate, study-specific questionnaires completed by the child's caregiver.

The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL 4.0™) (17). The PedsQL 4.0 is a 23 item, evidence-based measure evaluating perceptions of pediatric HRQOL by youth self-report and parent-proxy report. The generic measure includes four subscale scores (Physical, Emotional, Social, and School Functioning) and yields a Total HRQOL score and a Psychosocial Summary composite scale score. Items are answered on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = “never a problem” to 4 = “almost always a problem” over the past month) and reverse transformed to a 0-100 metric, with higher scores representing better HRQOL. Calculation of scale scores requires that at least 50% of the items in the scale are answered. This measure has demonstrated good reliability and validity across pediatric populations, with internal consistency estimates ranging from .68 to .90 (13, 14, 17-19). Internal consistency estimates across subscales ranged from .72 to .93 across conditions in this study.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics and frequencies were calculated for the total sample and for each illness group. Chi-square analyses were completed to test for between-group differences in age (i.e., child, ages 2-12 years; teenager, 13-18 years), gender, racial minority status (i.e., Caucasian or racial minority (i.e., African American, Asian, other)), and caregiver marital status (i.e., married or not currently married (i.e., divorced, single)). Demographic variables that differed significantly between groups (p < .05) were entered as covariates into subsequent multivariate models for primary analyses. Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA) models tested for differences across Emotional, Social, and School Functioning subscales for both youth self-reported and parent-proxy reported HRQOL. Due to differences in sample size (i.e., participants diagnosed with type 1 diabetes did not complete the physical subscale) and requirements of MANOVA testing (i.e., individual HRQOL subscales are used to calculate composite psychosocial summary and total scores) separate Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) models were used to examine differences across the Total, Psychosocial Summary, and Physical Functioning scores. Bonferroni-corrected, univariate follow-up tests were used to examine individual differences between groups as appropriate. Exploratory analyses examined differences in HRQOL to previously published data for healthy youth. Paired sample t-tests were used to determine differences in youth self-reported and parent-proxy-reported of HRQOL across groups. Given the number of comparisons, differences by reporter in individual groups were not examined. All analyses were conducted in SPSS 15.0 for Windows.

RESULTS

Youth participants were 47% female, primarily Caucasian (72% Caucasian, 24% African American, 1% Hispanic, 1% Asian, and 3% other), and ranged in age from 2.0-18.8 years (11.8 ± 4.3). Caregivers completing parent-proxy report assessments were primarily mothers (85% mothers, 7% fathers, 2% step-parents, 3% grandparents, and 3% other) and currently married (63% married, 17% single, 16% separated/divorced, and 4% other). Demographic characteristics by condition are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants by disease group

| Obesity | CF | EGID | IBD | Epilepsy | Diabetes | SCD | Renal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 119 | 63 | 54 | 34 | 105 | 150 | 35 | 29 |

| Child age | 11.0±3.1 | 12.7±4.3 | 8.4±4.2 | 15.4±1.4 | 7.3±2.8 | 15.5±1.4 | 10.7±4.4 | 14.9±3.2 |

| Female child gender | 65.5% | 55.6% | 24.1% | 38.2% | 35.2% | 51.3% | 34.3% | 41.4% |

| Child race | ||||||||

| African American | 50.4% | 1.6% | - | 8.8% | 17.1% | 11.3% | 97.1% | 24.1% |

| Caucasian | 43.7% | 96.8% | 94.4% | 88.2% | 74.3% | 86.0% | - | 75.9% |

| Other | 5.9% | - | 5.7% | 2.9% | 8.6% | 2.7% | 2.9% | - |

| Missing | - | 1.6% | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Relationship to child | ||||||||

| Mother | 83.2% | 76.2% | 100.0% | 91.2% | 81.0% | 86.7% | 71.4% | 82.8% |

| Father | 5.0% | 7.9% | - | - | 14.3% | 10.0% | - | 3.4% |

| Other | 12.0% | 12.7% | 8.8% | 4.8% | 3.3% | 28.6% | 13.8% | |

| Missing | - | 3.2% | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Caregiver marital status | ||||||||

| Single | 35.3% | 6.3% | 7.4% | 2.9% | 19.0% | 5.3% | 45.7% | 13.8% |

| Married | 37.0% | 79.4% | 81.5% | 88.2% | 63.8% | 74.7% | 20.0% | 65.5% |

| Separated/divorced | 23.5% | 11.1% | 11.1% | 5.9% | 15.2% | 16.7% | 28.6% | 6.9% |

| Other | 4.2% | 1.6% | - | 2.9% | 2.0% | 3.4% | 5.8% | 13.8% |

| Missing | - | 1.6% | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Income | ||||||||

| < $50,000 | 74.8% | 44.4% | 29.6% | 8.8% | 53.3% | - | 68.6% | 48.3% |

| ≥ $50,000 | 23.5% | 54.0% | 64.8% | 82.4% | 46.7% | - | 20.0% | 44.8% |

| Missing | 1.7% | 1.6% | 5.6% | 8.8% | - | 100% | 11.4% | 6.9% |

| Study type | C | C | C | L | L | L | C | C |

Note. Study type abbreviations: C (cross-sectional), L (longitudinal).

Group Differences in Demographic Variables across Chronic Conditions

Significant differences were observed between groups across the following demographic variables: youth age (χ2(7) = 346.40, p < .001), youth gender (χ2(7) = 40.32, p < .001), youth minority status (χ2(7) = 191.45, p < .001), and caregiver marital status (χ2(7) = 97.12, p < .001). These variables were statistically controlled for in all subsequent multivariate analyses.

Group Differences in HRQOL across Chronic Conditions

Youth self-report

The MANCOVA model, including covariates of youth age, gender, minority status, and caregiver martial status, revealed a significant overall effect of disease group (F(21,1479) = 3.35, p < .001). Follow-up univariate tests revealed a significant effect of disease group on the Social Functioning subscale score (F(7,493) = 5.43, p < .001). The effects of disease group on the Emotional Functioning subscale score (p = .26) and School Functioning subscale score (p = .17) were not significant. Three separate ANCOVAs, also including demographic covariates, revealed a significant effect for disease group on the Psychosocial Summary score (F(7,496) = 2.06, p < .05). The effects of disease group on the Total score (p = .06) and Physical Functioning subscale score (p = .20) were not significant. Individual differences between groups are shown in Table 2. Of note, youth in the obese group reported lower HRQOL by self-report in the social functioning domain compared to youth with CF (p < .01), epilepsy (p < .001), and type 1 diabetes (p < .001).

Table 2.

Participant HRQOL by youth self-report and parent-proxy report

| Obesitya | CFb | EGIDc | IBDd | Epilep.e | Type 1f | SCDg | Renalh | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth | (n = 119) | (n = 60) | (n = 43) | (n = 34) | (n = 46) | (n = 150) | (n = 28) | (n = 28) | (n = 508) |

| Physical | 74.0±18.6 | 83.1±13.6 | 72.4±16.6 | 82.1±17.1 | 79.8±14.1 | - | 73.1±19.0 | 77.7±14.5 | 76.1±17.5 |

| Emotional | 66.6±22.2 | 72.8±17.6 | 64.0±17.0 | 75.6±19.5 | 73.2±18.3 | 68.2±21.3 | 71.9±19.9 | 74.2±21.3 | 69.0±20.6 |

| Social | 66.6±24.4b,e,f | 86.4±15.0a | 72.0±23.1 | 83.4±19.5 | 80.3±17.7a | 86.6±15.0a | 74.7±19.4 | 80.1±18.4 | 78.4±20.8 |

| School | 66.0±20.4 | 73.6±19.1 | 58.5±20.7 | 71.3±23.1 | 67.8±18.7 | 66.4±18.4 | 58.8±21.5 | 67.3±16.6 | 65.9±19.8 |

| Psychosocial | 66.4±18.0 | 77.7±14.2 | 64.8±16.5 | 76.7±18.5 | 73.8±13.8 | 73.7±14.6 | 68.4±18.0 | 73.9±15.9 | 71.2±16.5 |

| Total | 69.1±17.1 | 79.5±13.1 | 67.5±13.3 | 78.6±16.5 | 75.9±12.8 | 73.7±14.6 | 70.0±16.5 | 75.2±13.9 | 72.6±15.4 |

| Parent-proxy | (n = 119) | (n = 59) | (n = 54) | (n = 34) | (n = 103) | (n = 150) | (n = 35) | (n = 29) | (n = 583) |

| Physical | 63.5±20.9d,e,g | 73.0±17.9dc | 66.0±20.6d,e | 87.0±13.3a,b,c,h | 83.9±17.4a,c | - | 75.1±23.5a | 68.4±24.5d | 73.0±21.4 |

| Emotional | 64.5±20.2e,g | 69.4±17.0c | 56.5±18.8b,d,e,f,g,h | 75.7±23.1c | 76.7±18.6a,c | 70.1±18.4c | 81.3±18.5a,c | 68.8±22.6c | 69.7±20.1 |

| Social | 61.1±22.3b,d,e,f,g | 81.5±17.1a | 69.9±20.1d,e,f | 85.1±17.2a,c | 81.4±18.4a,c | 84.2±16.3a,c | 77.9±21.4a | 71.8±22.4 | 76.4±21.0 |

| School | 63.9±22.8c | 68.5±20.0c | 52.5±22.2a,b,d,e,f | 76.8±20.3c,h | 73.0±19.3c | 68.2±20.2c | 63.7±25.7 | 55.7±26.5d | 66.3±22.3 |

| Psychosocial | 63.2±17.7b,d,e,f,g | 73.1±14.4a,c, | 60.2±17.2b,d,e,f,g | 79.2±18.1a,c,h | 77.4±15.5a,c | 74.2±14.8a,c | 74.5±19.0a,c | 65.4±19.9c | 71.0±17.5 |

| Total | 63.3±17.7b,d,e,f,g | 73.0±14.5a,c | 62.3±16.8b,d,e,f,g | 81.9±15.0a,c,h | 79.8±14.7a,c | 74.2±14.8a,c | 74.6±18.8a,c | 66.4±20.1d | 71.8±17.3 |

Note: Significant univariate differences between groups indicated using alpha superscripts (a-h), bonferroni adjusted for multiple comparisons, p < .05.

Parent-proxy report

The MANCOVA model, including covariates of youth age, gender, minority status, and caregiver marital status, revealed a significant overall effect (F(21,1647) = 7.23, p < .001). Follow-up univariate tests revealed a significant effect for disease group on the Emotional Functioning (F(7,549) = 8.32, p < .001), Social Functioning (F(7,549) = 12.74, p < .001), and School Functioning (F(7,549) = 6.60, p < .001) subscale scores. Individual differences between groups are shown in Table 2. Caregivers of youth diagnosed with EGID reported significantly lower perceptions of youth emotional HRQOL than youth diagnosed with CF (p < .01), IBD (p < .001), epilepsy (p < .001), type 1 diabetes (p < .001), SCD (p < .001), and youth receiving a renal transplant (p < .05). Caregivers of youth diagnosed with EGID also reported perceptions of lower youth HRQOL in the school domain than youth diagnosed with obesity (p < .05), CF (p < .01), IBD (p < .001), epilepsy (p < .001), and type 1 diabetes (p < .01). Caregivers of youth in the obese group reported significantly worse perceptions of youth social HRQOL than youth with CF (p < .001), IBD (p < .001), epilepsy (p < .001), type 1 diabetes (p < .001), and SCD (p < .01).

Results from three separate ANCOVAs, including the same demographic covariates, revealed a significant effect for disease group on the Total score (F(7,571) = 13.36, p < .001), Psychosocial Summary score (F(7,571) = 11.62, p < .001), and the Physical Functioning subscale score (F(6,422) = 12.31, p < .001). Of note, caregivers of youth diagnosed with EGID reported significantly lower overall youth HRQOL than youth diagnosed with CF (p < .05), IBD (p < .001), epilepsy (p < .001), type 1 diabetes (p < .001), and SCD (p < .01). Caregivers of youth in the obese group reported worse youth physical HRQOL than youth with IBD (p < .001), epilepsy (p < .001), and SCD (p < .05). Results are further summarized in Table 2.

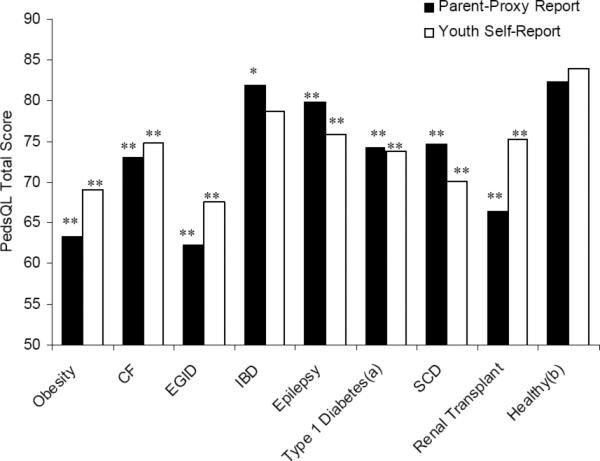

Differences in total HRQOL scores between disease groups by both youth self-report and parent-proxy report are further illustrated in Figure 1. Additional exploratory analyses revealed significant differences compared to previously reported HRQOL of healthy youth (18). Excluding parent-proxy reports of youth diagnosed with IBD, chronically ill youth experienced lower HRQOL than healthy youth across all disease groups.

Figure 1.

PedsQL total scores comparing chronic conditions to healthy comparison group * p < .05, ** p < .01

a Type 1 diabetes total score does not include Physical Symptoms subscale

b Healthy comparison group (18)

Differences in Self-Report and Parent-Proxy Report of HRQOL

Collapsing across conditions, significant differences between parent-proxy and youth self-reported HRQOL were found across all subscales of the PedsQL 4.0. Parent-proxy HRQOL scores were significantly lower across the Physical Functioning subscale (t(354) = -4.20, r = .43, p < .001), Emotional Functioning subscale (t(504) = -.01, r = .38, p < .001), Social Functioning subscale (t(504) = -2.30, r = .45, p < .001), Psychosocial Summary (t(504) = -1.00, r = .48, p < .001), and Total (t(320) = -2.14, r = .47, p < .001) scale score compared to youth self-report. Parent-proxy HRQOL scores were significantly higher than youth self-reported HRQOL on the School Functioning subscale (t(504) = .10, r = .47, p < .001).

DISCUSSION

The current study is one of few available examining HRQOL by youth self-report and parent-proxy report across different chronic illness groups. Similar to other research in this area (12-14), these findings document important differences in HRQOL between eight chronic conditions. Moreover, results provide important preliminary information regarding patient-reported outcomes of previously understudied disease groups. While a relatively large body of literature exists examining the HRQOL of youth with obesity (14), diabetes (20), and CF (21), few studies examine the general functioning of youth diagnosed with IBD, EGID, SCD, post-renal transplantation, and epilepsy. Previous research regarding the factor structure of the PedsQL provides confidence that differences in scores obtained between these disease groups are due to actual perceived differences in HRQOL rather than differences due to measurement error (22). Combined with current findings, this suggests that certain chronic illnesses may be associated with poorer generic HRQOL across multiple domains of functioning compared to other chronic illnesses as well as compared to healthy youth (see Figure 1) (18).

For youth with EGID, caregivers reported that youth experienced consistently lower HRQOL than caregivers of youth with other chronic illnesses across domains of emotional and school functioning and overall HRQOL. The impact on HRQOL, particularly in the emotional functioning domain, may be explained, in part, by the low prevalence of EGID in the general pediatric population (23). Fewer opportunities to meet other youth with a similar diagnosis may lead to feelings of isolation and/or lack of understanding from peers, which may have a stigmatizing effect. In addition, uncertainty regarding possible exacerbation triggers and lack of standardized treatment and definitive disease course may increase fear and anxiety. Given the need for long-term daily medication, frequent clinic visits, and procedures that might limit youth's ability to regularly attend school are factors shared across other chronic illness groups in this study; further research is needed to place findings of lower academic functioning in EGID within an appropriate context. Given the lack of HRQOL data in this population (24), future research should examine disease-specific HRQOL factors and their relationship to health outcomes. Such research may have implications for effectively tailoring interventions to improve HRQOL in this population.

In contrast to youth with EGID, caregivers described the HRQOL of youth in the obese sample as significantly worse than other youth across domains of physical and social functioning. These differences are understandable given results from several studies that describe relationships between decreased social support and increased rates of peer victimization in this population (25, 26). The subsequent impact of these variables on physical activity and general physical limitations associated with obesity are also well documented (25-27) and help explain the lower rates of physical and social HRQOL observed in the current study. Additional clinical attention, assessment, and intervention across these domains may be necessary. For example, interventions targeting youth who are obese may require specific attention to social domains of functioning (e.g., social skills, peer support, strategies to cope adaptively with teasing) to help improve the HRQOL of these youth.

Similar to other studies examining differences between parent-proxy and youth self-report of HRQOL (7-9), the current study found that caregivers reported lower HRQOL by proxy-report than did youth collapsing across all disease groups. That this finding was true for all HRQOL subscales other than School Functioning suggests important differences in how patients and caregivers perceive patient HRQOL. Although patient self-reported HRQOL is typically considered the gold standard in HRQOL measurement (19), most researchers agree that parent-proxy reports provide valuable information regarding patient well-being (7). Caregivers are often asked in clinical settings to assess youth's psychosocial functioning, which may guide treatment decisions. Moreover, factors such as child age or physical and/or cognitive functioning might preclude use of self-reported HRQOL. For situations in which youth self-report is unfeasible, greater understanding of factors influencing caregiver's ratings of their child's HRQOL is necessary. While research examining the impact of caregivers’ own HRQOL on proxy-reported functioning is mixed (28), some data suggest that caregivers of chronically ill youth experience worse HRQOL themselves and that caregiver HRQOL may influence their rating of youth's HRQOL (29, 30). Future research should further clarify reasons for the differences between parent-proxy and patient self-report HRQOL as well as the factors that influence caregivers’ perceptions of youth's HRQOL.

Taken together, these findings provide clinicians information regarding the HRQOL of youth across different chronic health conditions. While youth may be seen in specialized, multidisciplinary pediatric clinics for care related to their condition, they are also followed by primary care providers who see a more diverse population of youth. In light of recent data indicating that lower perceived HRQOL is associated with greater health care use independent of other health-related and demographic factors (31), increased awareness of patient HRQOL is important for providers and the health care system in general. Measures of HRQOL can provide clinicians a relatively simple, but informative glimpse into their patients’ overall well-being. For example, the PedsQL™ provides clinicians a brief, easily scored, and reliable patient-reported outcome measure that can be quickly incorporated into daily practice. By asking families to complete HRQOL measures while awaiting their scheduled appointment, providers are able to assess their patients’ HRQOL and provide relevant point-of-care feedback, recommendations, or referrals. Development of internet-based assessment and scoring of HRQOL is currently underway (32) and may further improve the measure's feasibility in such settings. Its use may also increase awareness of HRQOL differences across chronic conditions to help inform treatment approaches and policy decision making. Specific differences documented in the current study also highlight certain pediatric populations which may require more careful consideration (i.e., EGID, obesity). Clinicians might be more sensitive to the impact of obesity on physical and social functioning or the particular risk for poorer emotional functioning in youth diagnosed with EGID compared to other conditions. Such assessment provides an opportunity for recommendations regarding intervention or referral services (e.g., social work referral to enable an Individualized Education Plan, psychological treatment to address peer victimization) that may help improve HRQOL for a particular patient.

There are important limitations of this study that warrant discussion. First, considerable variation existed across disease groups in regard to demographic and disease-specific sample characteristics. While this was expected given the secondary nature of data collection and differences were statistically controlled through data analyses, future studies would benefit from a-priori matching of participants across these factors during recruitment. Second, despite researchers’ efforts to maximize recruitment within each of their respective populations, differences in sample sizes existed across disease groups. Although these differences are similar to known disease prevalence rates, future studies recruiting equal sample sizes across groups will provide confirmatory data. In addition, participants in the diabetes group did not complete all subscales of the HRQOL measure, which precluded inclusion of this condition in HRQOL Physical Functioning score analyses. Third, the use of a statistical correction factor may have limited the detection of significant results. However, given the relative novelty of studying these groups, more conservative analyses were considered necessary. Fourth, the cross-sectional nature of the study limits the conclusions drawn with respect to the temporal nature of HRQOL changes across disease groups. Longitudinal studies examining these groups will better clarify HRQOL trajectories over time, possible fluctuation in differences across conditions, and thus, data regarding optimal timing of interventions to improve HRQOL. Fifth, given the number of comparisons conducted, analyses examining differences by parent-proxy and youth self-report of HRQOL were collapsed across disease groups. It may be that differences by reporter are more salient for particular disease groups and are driving current results.

Despite these limitations, this study provides important information regarding differences in patient HRQOL across various conditions, especially in previously understudied populations. Findings highlight areas for providers to focus clinical attention, assessment, and intervention when working with these youth in their practice. Future studies examining HRQOL measurement in pediatric primary care clinics will help provide further support regarding its utility in general pediatric practice as well as improvement in clinical outcomes resulting from increased assessment and intervention in patients with poor HRQOL. Additionally, cost-effectiveness analysis of HRQOL assessment in pediatric primary care will help determine its value-added contribution to health care and possibility for adoption by pediatric providers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

NIDDK K23 DK079037, PHS Grant P30 DK 078392, Procter and Gamble Pharmaceuticals Prometheus Laboratories, Inc. to K.A.H.; K23 DK60031, Clinical Research Feasibility Funds, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, General Clinical Research Center, U.S. Public Health Service, General Clinical Research Centers Program, National Center for Research Resources/NIH M01 RR08094 to M.Z.; NIH K23 HD057333 to A.C.M.; NIH T32 DK63929 to A.C.M., C.P.W., and K.D.; NIDDK K23 DK 073340 to K.K.H.

ABBREVIATIONS

- HRQOL

health-related quality of life

- EGID

eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorder

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- SCD

sickle cell disease

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- PedsQL

Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory

- ANCOVA

analysis of covariance

- MANCOVA

multivariate analysis of covariance

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

REFERENCES

- 1.Newacheck PW, Strickland B, Shonkoff JP, Perrin JM, McPherson M, McManus M, et al. An epidemiologic profile of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 1998;102:117–123. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resnikoff JR, Conrad DJ. Recent advances in the understanding and treatment of cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 1998;4:130–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Food and Drug Administration Guidance for industry. Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. [30, 2009];2006 doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-79. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/cder/guidance/5460dft.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Eiser C, Morse R. A review of measures of quality of life for children with chronic illness. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84:205–211. doi: 10.1136/adc.84.3.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schor EL. The future pediatrician: promoting children's health and development. J Pediatr. 2007;151:S11–S16. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rolland JS. Toward a psychosocial typology of chronic and life-threatening illness. Family Systems Medicine. 1984;2:245–262. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eiser C, Morse R. Can parents rate their child's health-related quality of life? Results of a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:347–357. doi: 10.1023/a:1012253723272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cremeens J, Eiser C, Blades M. Factors influencing agreement between child self-report and parent proxy-reports on the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ 4.0 (PedsQL™) generic core scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Upton P, Lawford J, Eiser C. Parent-child agreement across child health-related quality of life instruments: a review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2008;17:895–913. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9350-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leslie L, Rappo P, Abelson H, Jenkins RR, Sewall SR, Chesney RW, et al. Final report of the FOPE II pediatric generalists of the future workgroup. Pediatrics. 2000;106:1199–1223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wise PH. The future pediatrician: the challenge of chronic illness. J Pediatr. 2007;151:S6–S10. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beattie PE, Lewis-Jones MS. A comparative study of impairment of quality of life in children with skin disease and children with other chronic childhood diseases. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:145–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Varni J, Limbers C, Burwinkle T. Impaired health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with chronic conditions: a comparative analysis of 10 disease clusters and 33 disease categories/severities utilizing the PedsQL™ 4.0 generic core scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:43. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwimmer JB, Burwinkle TM, Varni JW. Health-related quality of life of severely obese children and adolescents. JAMA. 2003;289:1813–1819. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karwowski CA, Keljo D, Szigethy E. Strategies to improve quality of life in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009 doi: 10.1002/ibd.20919. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anthony SJ, Hebert D, Todd L, Korus M, Langlois V, Pool R, et al. Child and parental perspectives of multidimensional quality of life outcomes after kidney transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2009.01214.x. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varni J, Seid M, Kurtin P. The PedsQL™ 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ Version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care. 2001;39:800–812. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varni J, Burwinkle T, Seid M, Skarr D. The PedsQL™ 4.0 as a pediatric population health measure: feasibility, reliability, and validity. Ambul Pediatr. 2003;6:329–341. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2003)003<0329:tpaapp>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varni J, Limbers C, Burwinkle T. Parent proxy-report of their children's health-related quality of life: an analysis of 13,878 parents’ reliability and validity across age subgroups using the PedsQL™ 4.0 generic core scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-2. 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Wit M, Delemarre-van de Waal HA, Pouwer F, Gemke RJ, Snoek FJ. Monitoring health related quality of life in adolescents with diabetes: a review of measures. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:434–439. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.102236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quittner AL. Measurement of quality of life in cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 1998;4:326–331. doi: 10.1097/00063198-199811000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Limbers CA, Newman DA, Varni JW. Factorial invariance of child self-report across healthy and chronic health condition groups: a confirmatory factor analysis utilizing the PedsQL™ 4.0 generic core scales. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:630–639. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kugathasan S, Judd RH, Hoffmann RG, Heikenen J, Telega G, Khan F, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of children with newly diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease in wisconsin: a statewide population-based study. J Pediatr. 2003;143:525–531. doi: 10.1067/s0022-3476(03)00444-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hommel KA, Davis CM, Baldassano RN. Medication adherence and quality of life in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33:867–874. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeller MH, Reiter-Purtill J, Ramey C. Negative peer perceptions of obese children in the classroom environment. Obesity. 2008;16:755–762. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gray WN, Janicke DM, Ingerski LM, Silverstein JH. The impact of peer victimization, parent distress and child depression on barrier formation and physical activity in overweight youth. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008;29:26–33. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31815dda74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Storch EA, Milsom VA, DeBraganza N, Lewin AB, Geffken GR, Silverstein JH. Peer victimization, psychosocial adjustment, and physical activity in overweight and at-risk-foroverweight youth. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:80–89. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Modi AC, Guilfoyle SM, Zeller MH. Impaired health-related quality of life in caregivers of youth seeking obesity treatment. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34:147–155. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hatzmann J, Heymans H, Ferrer-i-Carbonell A, van Praag B, Grootenhuis MA. Hidden consequences of success in pediatrics: parental health-related quality of life-results from the care project. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e1030–1038. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldbeck L, Melches J. Quality of life in families with congenital heart disease. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1915–1924. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-4327-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berra S, Tebe C, Erhart M, Ravens-Sieberer U, Auquier P, Detmar S, et al. Correlates of use of health care services by children and adolescents from 11 European countries. Med Care. 2009;47:161–167. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181844e09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Varni JW. Measuring pediatric health-related quality of life from the perspective of children and their parents.. Midwest Conference on Pediatric Psychology; Kansas City, MO. April 2009; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]