Summary

In tuberculosis, infecting mycobacteria are phagocytosed by macrophages, which then migrate into deeper tissue and recruit additional cells to form the granulomas that eventually contain infection. Mycobacteria are exquisitely adapted macrophage pathogens and observations in the mouse model of tuberculosis have suggested that mycobacterial growth is not inhibited in macrophages until adaptive immunity is induced. Using the optically transparent and genetically tractable zebrafish embryo-Mycobacterium marinum model of tuberculosis, we have directly examined early infection in the presence and absence of macrophages. The absence of macrophages led rapidly to higher bacterial burdens suggesting that macrophages control infection early and are not an optimal growth niche. However, we show that macrophages play a critical role in tissue dissemination of mycobacteria. We propose that residence within macrophages represents an evolutionary trade-off for pathogenic mycobacteria that slows their early growth but provides a mechanism for tissue dissemination.

Introduction

Mycobacteria are facultative intracellular pathogens that infect and survive in host macrophages. Infected macrophages disseminate into the tissue and recruit additional macrophages and lymphocytes to form organized aggregates called granulomas where mycobacterial growth is restricted but not necessarily eradicated (Dannenberg, 1993; Flynn and Chan, 2001).

While macrophages are known to be key effectors in combating mycobacterial growth after the initiation of adaptive immunity, their role in the early stages of infection is unclear (Flynn and Chan, 2001; North and Jung, 2004). The ability to grow in cultured macrophages in the absence of stimuli from adaptive immunity is a key distinguishing feature between pathogenic and nonpathogenic mycobacteria (Cosma et al., 2003). In vitro studies have demonstrated that macrophages can significantly restrict pathogenic mycobacterial growth only upon co-incubation with lymphocytes or cytokines such as interferon-γ suggesting a requirement for adaptive immunity in countering bacterial survival strategies (Flesch and Kaufmann, 1990; Mackaness, 1969; Russell, 1995). Therefore, it is possible that mycobacterial growth is completely unrestricted in macrophages until they become activated by components of the adaptive immune response. In support of this hypothesis, pathogenic mycobacteria can use multiple receptors to gain entry into cultured macrophages (Ernst, 1998) and express factors that facilitate their uptake by macrophages (Mueller-Ortiz et al., 2001; Schorey et al., 1997), suggesting that the bacteria utilize the host macrophage as a specialized niche that they have evolved to survive in. On the other hand, cultured alveolar macrophages support higher growth of M. tuberculosis in the presence of glucocorticoids, suggesting that macrophages do curb bacterial growth using a steroid-sensitive mechanism in the absence of adaptive immune cues (Rook et al., 1987).

Studies in a variety of animal models of tuberculosis have found that mycobacterial numbers increase exponentially during early infection when only innate immunity operates, and plateau co-incident with the development of adaptive immunity (Alsaadi and Smith, 1973; Lazarevic et al., 2005; Lurie et al., 1952; Swaim et al., 2006). M. tuberculosis-infected mice depleted of macrophages had decreased bacterial loads and increased survival at five weeks post infection, an effect that was lost when only activated macrophages were depleted (Leemans et al., 2001; Leemans et al., 2005), suggesting that optimal mycobacterial growth is actually dependent on entry into macrophages. In addition, the induction of apoptosis that occurs in infected macrophages has been hypothesized to be a host protective response that deprives the mycobacteria of its ideal environmental niche (Fratazzi et al., 1999). Yet there is also evidence supporting the hypothesis that macrophages can restrict mycobacterial growth from early on. In the mouse model, genetic differences have been identified that influence the rate of mycobacterial replication within macrophages (Pan et al., 2005). However, the role of the macrophage in early tuberculosis when only innate immunity is operant has not been tested directly, owing to the complexity of the mammalian models that are traditionally used (North and Jung, 2004).

Mycobacterium marinum is a close genetic relative of M. tuberculosis and is used as a model to study mycobacterial pathogenesis (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/M_marinum/). M. marinum and M. tuberculosis both localize to similar subcellular compartments within infected macrophages (Barker et al., 1997). A subset of M. marinum is found in the cytoplasm associated with actin-based motility (Stamm et al., 2003). While actin motility has yet to be demonstrated for M. tuberculosis, it has also been found to localize to the cytosol of infected macrophages (McDonough et al., 1993; Myrvik et al., 1984). Therefore it is unresolved whether cytosolic localization represents a difference between the two organisms.

Zebrafish are natural hosts to M. marinum and develop organized caseating granulomas that are pathologically similar to those of M. tuberculosis (Cosma et al., 2004; Pozos and Ramakrishnan, 2004; Swaim et al., 2006). The zebrafish infection model also mimics mammalian models of tuberculosis in the rapid early increase in bacterial numbers and the dependence upon adaptive immunity for control of infection (Swaim et al., 2006). While the zebrafish has a complex innate and adaptive immune system similar to that of mammals, its embryos and early swimming larvae lack elements of adaptive immunity (Traver et al., 2003). The accessibility of developing zebrafish embryos before the development of adaptive immunity allows study of host-Mycobacterium interactions in the sole context of innate immunity (Traver et al., 2003) (Davis et al., 2002; Volkman et al., 2004). The embryo infection model recapitulates the early stages of tuberculosis including granuloma formation, demonstrating the same early rapid increase in bacterial numbers as well as the dependence on the same bacterial virulence determinants seen in the adult zebrafish and mammals (Cosma et al., 2006; Davis et al., 2002; Volkman et al., 2004).

We have taken advantage of the optical transparency and genetic tractability of the zebrafish embryo to directly dissect the role of the macrophage in early mycobacterial infection by comparing sequential events in embryos that have or lack macrophages. We find that macrophages respond rapidly to infection by migrating to the bacteria and upregulating cytokines. Higher bacterial burdens are rapidly achieved when macrophages are absent, demonstrating that the naïve macrophage curtails bacterial growth considerably. However, we find a critical role for macrophages in tissue dissemination of the mycobacteria, suggesting that these cells have a complex role in determining the outcome of early infection.

Results

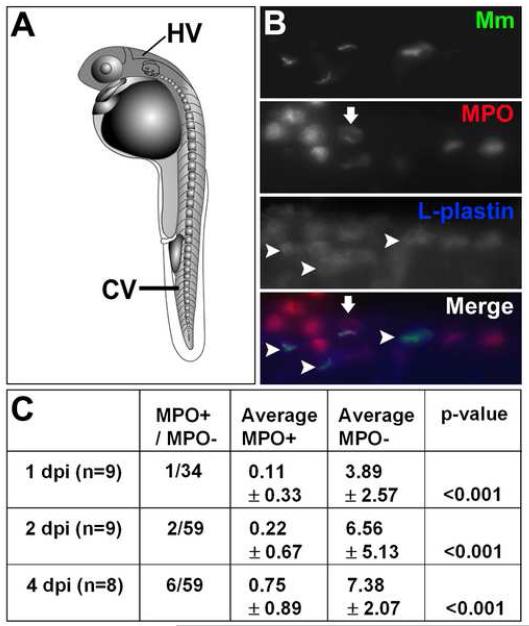

Macrophages, not neutrophils, phagocytose M. marinum early in infection

While macrophages are the main phagocytic cells of mycobacteria (Dannenberg, 1993; Flynn and Chan, 2001), neutrophils are found to interact with these bacteria in some infection models (Abadie et al., 2005). Zebrafish embryos have both macrophages and neutrophils (Clay, 2005). By differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy, the cells containing mycobacteria were morphologically similar to macrophages rather than to neutrophils (Mathias et al., 2006; Renshaw et al., 2006). In order to determine the extent to which neutrophils were phagocytosing mycobacteria, we performed dual fluorescent antibody detection of L-plastin, an actin-bundling protein present in both macrophages and neutrophils, and myeloperoxidase (MPO), an enzyme that is expressed only by neutrophils and not macrophages in the zebrafish (Clay, 2005; Mathias et al., 2006). Embryos injected with M. marinum via the caudal vein (Fig. 1A) were assessed for uptake of bacteria by MPO-positive cells. The majority of bacteria were found in L-plastin-positive, MPO-negative cells, indicating that while neutrophils are present, they are significantly less likely to phagocytose M. marinum (Fig. 1B and C). There is still the possibility that neutrophils are impacting infection by altering the activity of macrophages, as has been suggested in other systems (Tan et al., 2006).

Fig 1.

Macrophages are the primary cell to phagocytose M. marinum. A) Diagram of one day post fertilization (dpf) zebrafish embryo showing caudal vein (CV) and hindbrain ventricle (HV) injection sites. B) Dual fluorescent labeling of myeloperoxidase (MPO) and L-plastin antibodies in two dpf fish infected with green fluorescent M. marinum (Mm). Infected macrophages as indicated by L-plastin-positive, MPO-negative staining are indicated with arrowheads. An MPO-positive cell that is partially colocalized with GFP expressing bacteria is either adjacent to or possibly phagocytosing a bacterium is indicated with an arrow. Images are taken from the caudal vein. Scale bar, 25 μm. C) Numbers of infected MPO-positive cells versus all infected phagocytes in a low-dose infection (12 ± 3 CFU) analyzed at two, three, and five dpi. Data are presented as total number of infected MPO-positive cells out of total number of infected M. marinum- containing cells for all fish, and as average number of MPO-positive and negative cells per fish ± the standard deviation. Statistics were calculated using Student′s paired t-test for average numbers of MPO-positive versus MPO-negative cells per fish.

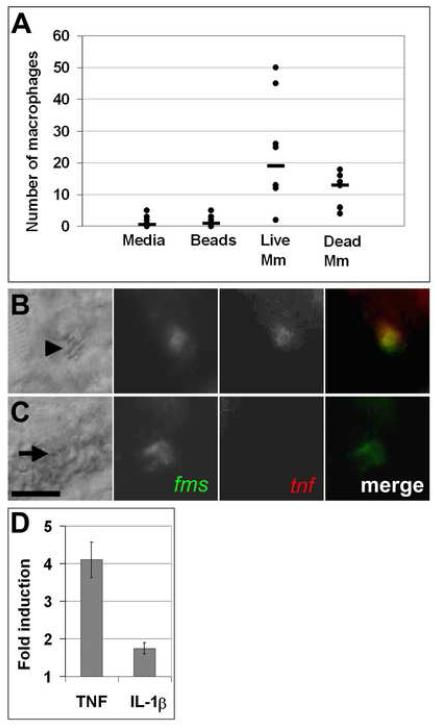

Macrophages migrate rapidly and specifically to mycobacteria and upregulate inflammatory cytokines

To examine the earliest interactions between mycobacteria and macrophages we injected mycobacteria or similar-sized fluorescent beads into the hindbrain ventricle at 30 hours post fertilization. The hindbrain ventricle (Fig. 1A) is a neuroepithelial-lined structure (Lowery and Sive, 2005) that normally has zero to two phagocytic cells at this time (Herbomel et al., 1999) and we had previously found that phagocytes are recruited to this cavity upon injection of mycobacteria (Davis et al., 2002). To test the specificity of this migration, we compared the number of cells in the hindbrain ventricle in response to injection of bacteria versus injection of like-sized latex particles or medium alone. Phagocytes arrived at the hindbrain ventricle within six hours in response to mycobacteria, but not in response to inert latex beads or injection medium (Fig. 2A). Both live and heat-killed bacteria recruited phagocytes, suggesting that cell wall lipids or heat stable proteins stimulate macrophage migration pathways (Krutzik and Modlin, 2004).

Fig 2.

Macrophages undergo rapid functional and molecular changes in response to mycobacterial infection. A) Graph of number of macrophages recruited six hours after HV injection. Mm is M. marinum. Medians are indicated by bars. Data from each condition were compared using a Kruskall-Wallis non-parametric ANOVA (p<0.0001). p<0.01 for all pair wise comparisons of medium or beads vs. live or dead bacteria. Difference in median number of macrophages recruited by live vs. dead bacteria was not significant. B, C) Differential interference contrast (DIC) (left) and fluorescence images of five dpf infected (B) and uninfected (C) embryos stained using double fluorescence in situ hybridization for c-fms (green) and tnf (red). Macrophages imaged here were in the caudal vein. Arrowhead in B indicates bacteria within a macrophage visible by DIC microscopy; arrow in C indicates position of uninfected macrophage. Scale bar, 10 μm. D) Quantitative real time PCR values for whole fish one dpi plotted as fold increase over mock injection for TNF at a low dose infection (32 ± 4 CFU, n = 3, p<0.05 using a one sample t-test against a hypothetical mean of 1.0) and IL-1β at a high dose infection (205 ± 38 CFU, n = 4, p<0.05). Error bars represent standard deviation.

The use of Fluorescent Whole Mount In Situ Hybridization (FISH) (Clay, 2005) indicated that infected cells expressed the macrophage marker c-fms, which encodes the receptor for macrophage colony stimulating factor (Fig. 2C) (Herbomel et al., 1999). To assess macrophage activation we looked for the induction of inflammatory cytokine expression, specifically Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF) and Interleukin 1β (IL-1β), in infected macrophages. Double FISH revealed that infected macrophages upregulate both TNF and IL-1β specifically in response to infection (Fig. 2B,C and data not shown), while neither cytokine was detectable in macrophages of uninfected embryos within 24 hours of M. marinum infection (Fig. 2C and data not shown). While FISH was unable to detect the expression of these cytokines in uninfected embryos, this does not rule out the possibility that uninfected macrophages in infected embryos upregulate proinflammatory cytokines, as DIC identification of bacteria following the FISH procedure is not always possible. It is also possible that these cytokines were induced in other cell types below the limit of detection of FISH. However, we were able to confirm TNF and IL-1β induction in whole infected embryos using quantitative real-time PCR (Fig. 2D). Taken together, these data show that macrophages respond rapidly and specifically to mycobacteria by migrating to sites of inoculation and upregulating key cytokines.

Mycobacterial growth is increased in the absence of macrophages

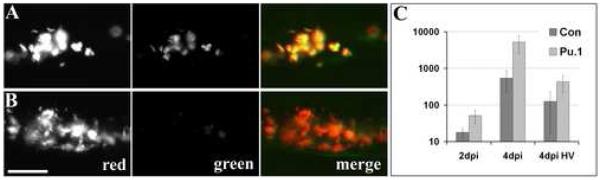

To determine the effect of macrophages on the growth of mycobacteria in vivo, we created embryos lacking macrophages by injection of modified anti-sense oligonucleotides (morpholino, or MO) directed against the myeloid transcription factor gene pu.1, creating embryos we will refer to as morphants (Rhodes et al., 2005). Consistent with previous results (Rhodes et al., 2005), DIC microscopy (Davis et al., 2002; Herbomel et al., 1999) revealed the lack of macrophages in the pu.1 morphants but not control embryos and these findings were confirmed by the absence of c-fms-positive cells by FISH (data not shown). As noted previously, there were some residual MPO-positive cells in the morphants (Rhodes et al., 2005).

While macrophages are almost completely lost in the first 48 hours, small numbers may reappear over the course of the next several days in some embryos as the MO is diluted by embryonic growth and as a second wave of hematopoiesis is initiated (Murayama et al., 2006; Nasevicius and Ekker, 2000). To confirm the loss of macrophages over time, we infected control and pu.1 morphants intravenously with M. marinum expressing the red fluorescent protein dsRed under a constitutive promoter and green fluorescent protein (GFP) under a macrophage-activated promoter (Cosma et al., 2004). Within seven hours post infection (hpi) of control embryos, all bacteria were both red and green fluorescent by virtue of being phagocytosed by macrophages (Fig. 3A). In contrast, almost none of the red fluorescent bacteria became green fluorescent in the pu.1 morphants, even at four days post infection (dpi) (Fig. 3B). Examination by DIC microscopy suggested that most, if not all, mycobacteria remained extracellular in the absence of macrophages. Notably, no increased uptake of mycobacteria by the small population of residual neutrophils in the pu.1 morphants was found over the low background levels found in the control fish (Fig. 1 B and C and data not shown).

Fig 3.

Mycobacteria achieve higher burdens in pu.1 morphant embryos lacking macrophages. Control (A) and pu.1 morphants (B) infected with map49::gfp;msp12::dsRed bacteria that are constitutively red fluorescent and both red and green fluorescent upon macrophage infection, shown here at four dpi. Scale bar, 50 μm. C) Mean bacterial colony forming units (CFUs) per embryo at two and four dpi. Error bars represent standard deviations. Mean CFUs from in control vs. pu.1 morphants were significantly different at both time points (p<0.01 at two dpi and four dpi, p<0.05 at four dpi HV using Student′s unpaired t-test). Inoculum for caudal vein infections was 35 ± 8 CFU, n=5 sets of four fish for each data set. Inoculum for hindbrain ventricle (HV) infections was 14 ± 5, n=5 sets of four control and n=4 sets of three pu.1 morphants.

To assess M. marinum growth in the presence and absence of macrophages, we compared bacterial loads in intravenously infected embryos by fluorescence microscopy and by enumerating bacterial counts. Mycobacterial burdens were higher in the absence of macrophages reaching a ten-fold difference per embryo at four dpi when injected into the blood stream (Figs. 3C and 4A and B). Bacterial burdens were also found to be significantly higher in the absence of macrophages when bacteria were injected into the HV (Fig. 3C) suggesting that macrophages rapidly curtail mycobacterial growth whether they first encounter these pathogens in the bloodstream or after traversing epithelial surfaces to the infection site.

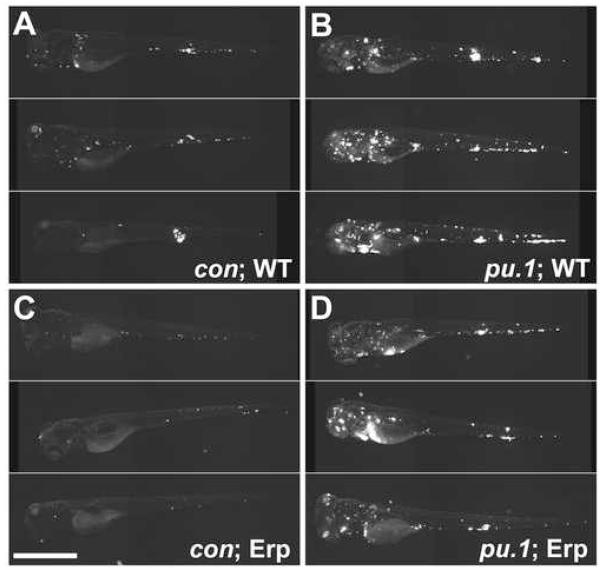

Fig 4.

The absence of macrophages rescues the growth defect of the M. marinum Erp-deficient mutant. For each condition, ten embryos were infected and monitored for four dpi. Images were obtained under the same settings for all embryos and assembled for each condition in descending order of fluorescence (indicating infectivity) as judged visually. Very little difference was noted within embryos in a given condition. The three most infected individual embryos are shown for each condition. Four dpi control (A, C) and pu.1 morphant (B, D) embryos infected with 50 ± 16 CFU of wild-type (A, B) or 56 ± 6 Erp-deficient M. marinum (C, D). Fluorescence represents infecting bacteria in all panels. Scale bar, 250 μm.

Consistent with the mouse pu.1 mutant phenotype which is embryonic lethal between 17-18 days (Scott et al., 1994), the zebrafish pu.1 morphants had variable mortality occurring after seven days post fertilization (dpf) depending on the penetrance of the morpholino. The morphants appeared morphologically normal during the course of our experiments and did not display increased susceptibility to the environmental microbes encountered in their conventional (non germfree) rearing conditions, suggesting a specific hypersusceptibility to macrophage pathogens, including mycobacteria. To address further the specificity of their hypersusceptibility to mycobacteria, we infected the pu.1 morphants with similar numbers of a nonpathogenic Escherichia coli strain and found that they cleared the bacteria rapidly in a time frame identical to control embryos (Supplementary Fig. 1). Second, the hypersusceptibility phenotype is unlikely to result from nonspecific effects preceding the embryonic lethal phenotype seen at and after seven days pf. The zebrafish earl grey (egy) mutant that is embryonic lethal at seven to eight dpf with thymic hypoplasia and other organ-specific defects but normal myeloid and erythroid lineages (Trede et al., 2007) has a normal response to M. marinum infection that is indistinguishable from wildtype embryos (Davis et al., 2002). We also examined infection in another embryonic lethal mutant, neurogenin 1 (ngn1), which has severe defects in primary neuron development and die between six and eight dpf (Cornell and Eisen, 2002; Golling et al., 2002). The ngn1 mutants have normal macrophages and the course and phenotype of M. marinum infection was found to be identical to clutch-matched controls (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Taken together these data strongly suggest that the hypersusceptibility of the pu.1 morphants to mycobacteria results from their lack of macrophages. The considerable restriction of mycobacterial growth by macrophages precedes cues from the adaptive immune system, which has not yet developed in the embryo, as well as granuloma initiation, which occurs after three to five days of infection (Davis et al., 2002).

The lack of macrophages rescues the growth attenuation of the mycobacterial virulence determinant Erp

Virulence determinants such as Erp exert their influence on virulence by enabling mycobacterial growth in macrophages from early on (Berthet et al., 1998; Cosma et al., 2006; Cosma et al., 2003). To test the specificity of the mode of action of such virulence determinants, we examined the course of infection of an Erp-deficient M. marinum strain (Cosma et al., 2006) in control versus pu.1 morphants. Due to the enhanced susceptibility of Erp-deficient bacteria to detergents in the embryo lysis buffer, CFU cannot be enumerated (Cosma et al., 2006) and we could assess bacterial burdens within the embryos only by microscopy. Erp-deficient bacteria showed the expected growth attenuation in control embryos by fluorescent microscopy (Cosma et al., 2006) (Fig. 4A and C). However, similar to the WT bacteria, the mutant bacteria attained much higher levels in the pu.1 morphants (Fig. 4B and D). This experiment shows that mycobacteria express virulence determinants that specifically allow them to overcome the restrictive growth environment found within macrophages in the context of innate immunity. However, despite the specific macrophage growth enhancement afforded by such determinants, the bacteria can only partially overcome macrophage defenses and fail to attain maximal growth in these cells.

Macrophages are required for early dissemination of mycobacteria into host tissue

In the absence of macrophages, bacteria grew rapidly to fill the compartments in which they were injected in the pu.1 morphant embryos, be it the vasculature in the case of intravenous injection, or the brain ventricle cavity in the case of hindbrain injections. DIC microscopy showed that these bacteria were growing extracellularly. However, it was unclear whether or not mycobacteria had access to deeper tissue in pu.1 morphants. Our finding that macrophages can substantially curtail mycobacterial growth even early in infection led us to speculate that the organisms might derive a different benefit from establishing early residence in macrophages, namely gaining dissemination into distant tissues. Macrophages are thought to carry mycobacteria into tissues where they aggregate into granulomas (Dannenberg, 1993). Similarly, our real-time visualization studies in the zebrafish embryo had shown Mycobacterium-infected macrophages traversing epithelial barriers (Davis et al., 2002). However, in vitro studies using transwells have suggested that while macrophages enhance mycobacterial transit across epithelial barriers, they are not required for it (Bermudez et al., 2002). Indeed, the mycobacterial RD1 virulence determinant had been suggested to mediate direct bacterial transit across epithelia, using indirect assessments based on the inability of RD1-deficient bacteria to lyse epithelial cells in culture (Hsu et al., 2003).

We were able to assess directly in vivo the role of macrophages in early mycobacterial dissemination by quantitating dissemination events in the presence and absence of macrophages. We made this assessment at 16 hpi so as to avoid two confounding variables occurring at later time points, namely the increased bacterial burdens that occurred starting around two days pi in the absence of macrophages (Fig 3C and data not shown) and the return of macrophages in some pu.1 morphants at later time points. While isolated macrophages would not substantially limit net bacterial growth, they would be sufficient to account for bacterial dissemination events in this assay.

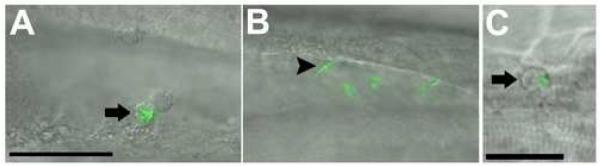

To establish infection, M. tuberculosis is proposed to first cross epithelial barriers and subsequently disseminate hematogenously to other sites within the lungs (Dannenberg, 1993; Harding and Smith, 1977; McMurray, 2003). Therefore, we wished to assess the role of macrophages in mycobacterial traversal of both epithelial and vascular endothelial barriers. First we determined whether bacteria that were injected into the hindbrain ventricle could disseminate into host tissue in the absence of macrophages (Fig. 5A-C). Bacteria disseminated out of the hindbrain ventricle in more than half of the control morphants, whereas none of the pu.1 morphants displayed any extraventricular bacteria (Table 1). All extraventricular bacteria were found to reside within phagocytes as determined by DIC microscopy, suggesting that macrophages are required for bacteria to cross the epithelial barrier of the hindbrain ventricle and gain access to additional host tissues.

Fig 5.

Infecting mycobacteria fail to disseminate to tissues in the absence of macrophages. A-C) Control and pu.1 morphants injected at 22 hpf into the hindbrain ventricle and scored for dissemination out of the ventricle at 16 hpi. Macrophages are visible in the ventricle of a control (A) embryo, an infected macrophage is indicated by an arrow. A pu.1 morphant (B) has extracellular bacteria (arrowhead) in the hindbrain with no evidence of macrophages in the cavity. Fluorescence is slightly blurred due to Brownian motion of unanchored bacteria in the cavity. C) An infected control macrophage has disseminated out of the hindbrain ventricle and is shown here in the trunk of the tail. Scale bars, 50 μm (A, B), 25 μm (C).

Table 1.

Macrophages are required for early dissemination of mycobacteria. Dissemination at 16hpi was assessed for bacteria injected into the hindbrain ventricle or into the caudal vein of fli1::egfp transgenic embryos. Embryos were scored for dissemination events and statistics were calculated using a contingency table and Fisher’s exact t-test.

| con | pu.1 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ventricle Dissemination |

6/10 | 0/10 | 0.011 |

| Vascular Dissemination |

9/11 | 2/10 | 0.003 |

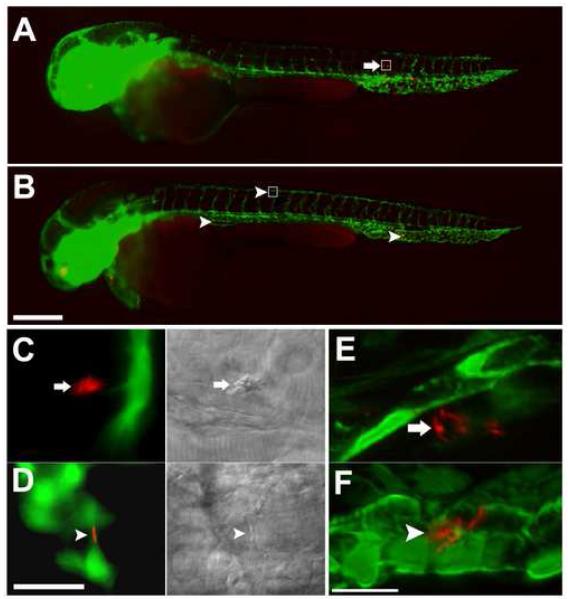

To determine if macrophages are required for hematogenous tissue dissemination of mycobacteria, we made use of the fli1:EGFP transgenic zebrafish line which expresses GFP throughout the vasculature (Lawson and Weinstein, 2002). Red fluorescent mycobacteria were injected into the bloodstream of control and pu.1 morphant fli1:EGFP embryos. Infected fish were monitored by fluorescent microscopy to determine whether or not bacteria could traverse the vascular endothelium in the absence of macrophages (Fig. 6). A significantly higher number of control embryos had extravascular bacteria compared to pu.1 morphants at 16 hpi (Table 1). All bacteria in the control embryos appeared to reside within phagocytes as determined by DIC and confocal microscopy. In the two pu.1 morphants that did have extravascular bacteria by 16 hpi, the bacteria appeared to be in residual macrophages as judged by DIC microscopy. To confirm our findings that bacteria were not traversing the vascular endothelium without macrophages, we examined the embryos at higher resolution by confocal microscopy. Three dimensional reconstruction images confirm that several bacteria in embryos with macrophages had traversed the vasculature whereas bacteria in hosts lacking macrophages remain within the vasculature (Fig. 6E and F and Supplemental movies 1 and 2). These data demonstrate that macrophages are required for mycobacterial traversal of both epithelial and endothelial barriers early in infection.

Fig 6.

Infecting mycobacteria remain in the vasculature in the absence of macrophages. fli1:EGFP transgenic embryos infected with 161 ± 10 red fluorescent bacteria imaged 16 hpi by widefield (A-D) or confocal microscopy (E, F). Whole fish overlays of green fluorescent vasculature and red fluorescent injected bacteria for control (A) and pu.1 morphants (B). Yolk and yolk extension appear red due to autofluorescence. Boxes in (A) and (B) are the areas shown magnified in (C) and (D), respectively. Arrows in control embryos show bacteria that do not colocalize with green fluorescent vasculature indicating they have migrated into tissue (A, C, E). DIC imaging in the right half of panel f shows that bacteria are within a macrophage. Arrowheads in pu.1 morphant shows a bacterium colocalizing with the vasculature indicating it has not migrated into tissues (B, D, F). DIC imaging in the right half of panel (D) shows that the bacterium is not in a macrophage. Three dimensional reconstruction images (maximum intensity) of 48 hpi control (E) and pu.1 morphant embryos (F). Movies of rotational views of these images are provided in supplemental movies 1 and 2 to show in greater detail the spatial relationship of the bacteria to the vasculature. Scale bars, 250 μm (A, B), 25 μm (C, D), 15μm (E, F).

Discussion

The zebrafish infection model, by allowing genetic manipulation of both host and pathogen, highlights the complex relationship between pathogenic mycobacteria and host phagocytes starting from their earliest encounter. By depleting macrophages in the sole context of innate immunity we have revealed a dual early role in simultaneously curtailing mycobacterial numbers while enabling these pathogens to establish systemic infection by disseminating them to deeper tissues. Our recent finding that M. marinum infection of zebrafish is moderated by adaptive immunity akin to M. tuberculosis infection of mice and humans (Swaim et al., 2006) suggests that the relative contribution of innate and adaptive immunity to the control of mycobacterial infection is similar in fish and mammals. Moreover, we have observed the same early increase in mycobacterial numbers in both adult and embryonic zebrafish occurs in mammalian models of tuberculosis (Swaim et al., 2006; Volkman et al., 2004). These findings in the zebrafish are consistent with the existing model based on M. tuberculosis infection of mammals including those based on aerosol infection of alveolar macrophages, that higher bacterial burdens are achieved in macrophages prior to the initiation of adaptive immunity. Therefore the results presented in this study that mycobacterial burdens are even higher in the absence of macrophages may also be relevant to mammalian tuberculosis.

The model that macrophages do little to curtail pathogenic mycobacterial growth without cues from adaptive immunity has been supported mainly by the mouse macrophage depletion studies concluding that M. tuberculosis numbers are lower in the context of nonselective depletion of host macrophages (Leemans et al., 2001; Leemans et al., 2005). However, these conclusions are problematic. Macrophage depletion resulted in lower lung bacterial counts only at five weeks but not at two weeks post infection, calling into question their conclusion that residence in naïve macrophages promotes mycobacterial growth. Rather these results suggest that macrophage depletion may have altered priming of the adaptive immune response. In support of this alternative interpretation, they found that macrophage depletion was associated with altered T-cell recruitment to the lung as well as dysregulation of both T-cell activating and T-cell produced cytokines (Leemans et al., 2001; Leemans et al., 2005). The failure of these studies to find the early bacterial growth enhancement in the absence of macrophages that we found could be due to differences between the models used. Alternatively, the partial macrophage depletion (~70%) achieved in prior studies may have decreased the extent of extracellularly growing mycobacteria.

Our findings in M. marinum are supported by epidemiological evidence from tuberculosis suggesting an early microbicidal activity of human macrophages against M. tuberculosis. First, there is evidence to suggest that innate immunity plays a role in clearing M. tuberculosis. Differential rates of PPD skin-test conversion, an indication that adaptive immunity has been invoked, in different populations with the same level of exposure to M. tuberculosis suggests genetic differences in the innate ability to clear infection (Stead, 2001). Additionally, epidemiological studies have linked host factors that are thought to operate during innate immunity, including vitamin D receptor, Nramp, and components of the complement and IL-1β pathways (Bellamy et al., 1999; Bellamy et al., 1998; Selvaraj et al., 1999; Wilkinson et al., 1999) to human susceptibility to tuberculosis.

Our dissection of the earliest mycobacterium-macrophage interaction is the first study to directly address the ability of innate macrophages to restrict pathogenic mycobacterial growth. Our data show that these primary host cells for mycobacteria do not provide them with an optimal niche if growth alone is considered. The question, then, is why these exquisitely host-adapted pathogens would reside in a cell that prevents maximal growth. Part of the answer may lie in the enhanced dissemination that is afforded by residence in macrophages. A number of intracellular pathogens utilize dissemination by host phagocytes to establish infection within specific host tissues. A recent study has demonstrated that Listeria monocytogenes requires a specific subpopulation of dendritic cells for efficient dissemination from blood into the spleen (Neuenhahn et al., 2006). Other intracellular pathogens such as salmonella have been shown to directly influence host cell motility in order to promote tissue invasion (Worley et al., 2006). While such a mycobacterial factor driving host cell dissemination has not been identified, the discovery that the mycobacterial virulence locus RD1 promotes macrophage aggregation into granulomas (Volkman et al., 2004) indicates that additional bacterial factors may enhance the ability of infected macrophages to gain entry into deeper tissues. Alternatively, bacterial factors may promote macrophage recruitment to the infection site, as shown in this study, and general mechanisms, inflammatory or homeostatic, may transport the infected macrophages back into the tissues. Whatever the mechanism, it is the ability of pathogenic mycobacteria to substantially evade macrophage effector functions early in infection that allows them to take advantage of these cells to gain access to deeper tissues.

Tissue dissemination may favor mycobacterial survival and growth by providing these organisms with a secluded niche where they can avoid competition from mucosal flora. Furthermore, taken together, our results suggest a model where mycobacteria may reside initially in macrophages and eventually lyse the host cell and grow extracellularly. Infected macrophage necrosis correlates with increased mycobacterial proliferation and virulence (Chen et al., 2006; Duan et al., 2002; Pan et al., 2005). A similar growth strategy is employed by salmonella, which also induces cell death after gaining entry into tissues via macrophages (Guiney, 2005). Alternatively, while initial tissue dissemination may favor the pathogen, the migration of infected phagocytes could also benefit the host as a mechanism for antigen presenting cells to prime the adaptive immune response. In particular, dendritic cells have been shown to participate in trafficking mycobacteria into the lymph nodes (Humphreys et al., 2006). Dendritic cell marker homologs such as CD11c have been identified in the zebrafish genome (http://www.ensembl.org/Danio_rerio/index.html) and cells resembling dendritic cells have been produced from long-term spleen cultures in other teleost fish (Bols et al., 1995). We do not see cells resembling dendritic cells in the zebrafish embryo, consistent with the finding that they develop later in ontogeny in the mouse (Dakic et al., 2004).

Therefore we cannot rule out the possibility in our experimental model that the dynamics of early bacterial trafficking may be different in the presence of dendritic cells.

Finally, submaximal growth within macrophages may be an evolutionary survival and transmission strategy for mycobacteria as it may prevent quickly overwhelming its host, enabling extensive transmission during chronic cavitary disease. This extensive co-adaptation of mycobacteria to host may have allowed them to be such successful pathogens over evolutionary time despite the lack of classical virulence determinants, such as toxins (Cosma et al., 2003). The new recognition of the substantial ability of macrophages to curtail pathogenic mycobacterial growth from very early in infection as well as their role in disseminating infection could provide a pharmacological starting point for new tuberculosis eradication strategies.

Experimental Procedures

Animal care and strains

Wild-type WIK zebrafish embryos were maintained and infected with bacteria as described (Cosma et al., 2006; Davis et al., 2002). Fli1:EGFP transgenic fish were obtained from ZIRC (http://zfin.org/zirc/home/guide.php). Neurogenin mutant fish were donated by David Raible. Infections were performed one day post-fertilization by injecting bacteria into the hindbrain ventricle or caudal vein.

Microscopy

DIC and widefield fluorescence pictures were taken and compiled as described (Davis et al., 2002; Volkman et al., 2004). Confocal images were acquired on an Olympus Fluoview 1000 laser scanning confocal microscope using a 20x air objective, N.A.=0.7. 3D datasets were deconvolved using Autoquant X software (Media Cybernetics, Inc.), starting from a theoretical point spread function and using ten iterations of an adaptive deconvolution algorithm. Maximum intensity reconstructions and movies were also produced on AutoQuant X.

Bacterial CFU enumeration

CFU counts were taken from whole embryos as follows: Pools of four fish were anaesthetized in microcentrifuge tubes with 4mg/mL Tricaine (Sigma A5040), supplemented with 20μg/mL of kanamycin and placed on ice for 30 minutes. Tubes were spun down briefly and the liquid was aspirated. The embryos were dissociated in100μL 0.1% Triton X-100 by smashing with a p-1000 pipette tip, then lysed by adding 100μL of Mycoprep™ reagent (BD BBL 240862) for nine minutes. After vortexing briefly and adding 1.3mL PBS, the homogenates were centrifuged for15 minutes. 1.2 mL of supernatant was removed and the remaining liquid was diluted in PBS supplemented with 0.05mg/mL BSA and 0.05% Tween80. Serial dilutions were plated on bacterial media supplemented with kanamycin. CFU were counted and plotted on a log scale by taking the number of bacteria on each plate dilution and dividing by the number of pooled fish (3 or 4) to calculate the number of CFU per embryo.

Fluorescent whole mount in situ hybridization

Fluorescent in situ hybridization was performed as described previously (Clay, 2005). Zebrafish tnf (ZFIN ID: ZDB-GENE-050317-1) was cloned from a moribund adult zebrafish cDNA pool constructed by isolating RNA from homogenized whole fish tissue using the Absolutely RNA™ RT-PCR Miniprep kit (Stratagene 400800) and cDNA was transcribed using the Accuscript ™ HF cDNA Kit (Stratagene 200820) as described by the manufacturer. Cloning primers used for TNF were F 5′-GACTGTGCAGGATCCATGAAGCTTGAGAGTC-3′ and R 5′ GATCGAGCTCCCGGGTCACAAACCAAACACCC-3′, and cloning primers for IL-1b were F 5′-ACGGATCCAGCTACAGATGCGACATGCA-3′ and R 5′-ACGAATTCCTTGAGTACGAGATGTGGAGA-3′.

Antibody staining

Embryos were fixed, dehydrated, and prepared as for in situs as described (Clay, 2005). The MPO antibody was made as described previously (Mathias et al., 2006). Polyclonal antibodies to zebrafish L-plastin were generated by injecting rabbits with a GST-L-plastin fusion protein that was purified as described previously (Bennin et al., 2002). The GST-L-plastin plasmid was a gift from Paul Martin. MPO and -L-plastin antibodies were incubated at 1:300 and 1:500, respectively, and visualized using TSA detection as described (Clay, 2005).

Real time PCR

All real time PCR experiments were performed with three biological replicates with the appropriate controls using SYBR® Green PCR Mix (Applied Biosystems 4309155) or Taqman® PCR Mix (Applied Biosystems 430447) on an ABI 7300 Real-Time PCR Machine at a 60°C annealing temperature. Briefly, bactches of 30-50 embryos were used per condition per biological replicate, and each biological replicate was run in triplicate on two separate plates to minimize any variation resulting from plating conditions. The six data points for each condition were averaged to create a single biological replicate data point. Fold increase for infected over mock-injected embryos was calculated using the ΔC method using β-actin as a reference. Biological replicates were averaged for statistical analysis. SYBR primers for IL-1β are described (Pressley et al., 2005). Taqman primers for tnf are F 5′- TTCCAAGGCTGCCATCCATTTA-3′ and R 5′-GGTCATCTCTCCAGTCTAAGGTCTT-3′, probe used was 5′ ACAGGTGGATACAACTCT-3′. RNA was extracted using TRIzol® Reagent (Invitrogen 15596-026) per manufacturers protocol. cDNA was transcribed as described above.

Morpholinos

Morpholinos were obtained from Genetools. Control MO were either the Pbx-2 mutant control MO described in Waskiewicz et. al. (Waskiewicz et al., 2002) (used for experiments done for Fig. 3) or 1mM of control MO supplied by Genetools (used for experiments done for Figs. 4 and 5). pu.1 MO oligos were designed to the transcription initiation site (CCTCCATTCTGTACGGATGCAGCAT ) and the exon 4-5 boundary (GGTCTTTCTCCTTACCATGCTCTCC) and combined to final concentrations of 0.375mM and 0.025mM respectively. 5 nL of MO mix was injected per embryo into the yolk at the 1-2 cell stage.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed by using In-Stat software (Graphpad Software, Inc).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Hannah Volkman for cloning the IL-1β gene, Astrid van der Saar for providing the bacterial CFU enumeration protocol, David Brennin for making the MPO and L-plastin antibodies, David Raible and Hillary McGraw for the neurogenin 1 mutant embryos, Laura Swaim and Heather Wiedenhoft for managing the zebrafish facility, and Robin Lesley, David Tobin, Kevin Urdahl and Christopher Wilson for discussions and review of the manuscript. This work was funded by grants from the NIH to LR, AH and SL (grant numbers RO1 AI036396 and RO1 AI54503 for LR, R01 GM074827 for AH, and K22 grant-F007309 for SL) and a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Award to LR. HC was funded in part by PHS NRSA T32 GM07270 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. JMD was funded by a fellowship from the U.S. Department of Defense.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abadie V, Badell E, Douillard P, Ensergueix D, Leenen PJ, Tanguy M, Fiette L, Saeland S, Gicquel B, Winter N. Neutrophils rapidly migrate via lymphatics after Mycobacterium bovis BCG intradermal vaccination and shuttle live bacilli to the draining lymph nodes. Blood. 2005;106:1843–1850. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsaadi AI, Smith DW. The fate of virulent and attenuated Mycobacteria in guinea pigs infected by the respiratory route. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1973;107:1041–1046. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1973.107.6.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker LP, George KM, Falkow S, Small PL. Differential trafficking of live and dead Mycobacterium marinum organisms in macrophages. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1497–1504. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1497-1504.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellamy R, Ruwende C, Corrah T, McAdam KP, Thursz M, Whittle HC, Hill AV. Tuberculosis and chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Africans and variation in the vitamin D receptor gene. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:721–724. doi: 10.1086/314614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellamy R, Ruwende C, Corrah T, McAdam KP, Whittle HC, Hill AV. Variations in the NRAMP1 gene and susceptibility to tuberculosis in West Africans. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:640–644. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803053381002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennin DA, Don AS, Brake T, McKenzie JL, Rosenbaum H, Ortiz L, DePaoli-Roach AA, Horne MC. Cyclin G2 associates with protein phosphatase 2A catalytic and regulatory B’ subunits in active complexes and induces nuclear aberrations and a G1/S phase cell cycle arrest. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27449–27467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111693200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez LE, Sangari FJ, Kolonoski P, Petrofsky M, Goodman J. The efficiency of the translocation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis across a bilayer of epithelial and endothelial cells as a model of the alveolar wall is a consequence of transport within mononuclear phagocytes and invasion of alveolar epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2002;70:140–146. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.1.140-146.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthet FX, Lagranderie M, Gounon P, Laurent-Winter C, Ensergueix D, Chavarot P, Thouron F, Maranghi E, Pelicic V, Portnoi D, et al. Attenuation of virulence by disruption of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis erp gene. Science. 1998;282:759–762. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bols NC, Yang BY, Lee LE, Chen TT. Development of a rainbow trout pituitary cell line that expresses growth hormone, prolactin, and somatolactin. Mol Mar Biol Biotechnol. 1995;4:154–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Gan H, Remold HG. A mechanism of virulence: virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain H37Rv, but not attenuated H37Ra, causes significant mitochondrial inner membrane disruption in macrophages leading to necrosis. J Immunol. 2006;176:3707–3716. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay H, Ramakrishnan L. Multiplex Fluorescent in situ hybridization in zebrafish embryos using tyramide signal amplification. Zebrafish. 2005;2:105–111. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2005.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell RA, Eisen JS. Delta/Notch signaling promotes formation of zebrafish neural crest by repressing Neurogenin 1 function. Development. 2002;129:2639–2648. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.11.2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosma CL, Humbert O, Ramakrishnan L. Superinfecting mycobacteria home to established tuberculous granulomas. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:828–835. doi: 10.1038/ni1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosma CL, Klein K, Kim R, Beery D, Ramakrishnan L. Mycobacterium marinum Erp is a virulence determinant required for cell wall integrity and intracellular survival. Infect Immun. 2006;74:3125–3133. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02061-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosma CL, Sherman DR, Ramakrishnan L. The secret lives of the pathogenic mycobacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:641–676. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.091033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakic A, Shao QX, D’Amico A, O’Keeffe M, Chen WF, Shortman K, Wu L. Development of the dendritic cell system during mouse ontogeny. J Immunol. 2004;172:1018–1027. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannenberg AM., Jr. Immunopathogenesis of pulmonary tuberculosis. Hosp Pract (Off Ed) 1993;28:51–58. doi: 10.1080/21548331.1993.11442738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JM, Clay H, Lewis JL, Ghori N, Herbomel P, Ramakrishnan L. Real-time visualization of mycobacterium-macrophage interactions leading to initiation of granuloma formation in zebrafish embryos. Immunity. 2002;17:693–702. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00475-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan L, Gan H, Golan DE, Remold HG. Critical role of mitochondrial damage in determining outcome of macrophage infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2002;169:5181–5187. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.5181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst JD. Macrophage receptors for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1277–1281. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1277-1281.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flesch IE, Kaufmann SH. Activation of tuberculostatic macrophage functions by gamma interferon, interleukin-4, and tumor necrosis factor. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2675–2677. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.8.2675-2677.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn JL, Chan J. Immunology of tuberculosis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:93–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratazzi C, Arbeit RD, Carini C, Balcewicz-Sablinska MK, Keane J, Kornfeld H, Remold HG. Macrophage apoptosis in mycobacterial infections. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:763–764. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.5.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golling G, Amsterdam A, Sun Z, Antonelli M, Maldonado E, Chen W, Burgess S, Haldi M, Artzt K, Farrington S, et al. Insertional mutagenesis in zebrafish rapidly identifies genes essential for early vertebrate development. Nat Genet. 2002;31:135–140. doi: 10.1038/ng896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiney DG. The role of host cell death in Salmonella infections. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;289:131–150. doi: 10.1007/3-540-27320-4_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding GE, Smith DW. Host-parasite relationships in experimental airborne tuberculosis. VI. Influence of vaccination with Bacille Calmette-Guerin on the onset and/or extent of hematogenous dissemination of virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis to the lungs. J Infect Dis. 1977;136:439–443. doi: 10.1093/infdis/136.3.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbomel P, Thisse B, Thisse C. Ontogeny and behaviour of early macrophages in the zebrafish embryo. Development. 1999;126:3735–3745. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu T, Hingley-Wilson SM, Chen B, Chen M, Dai AZ, Morin PM, Marks CB, Padiyar J, Goulding C, Gingery M, et al. The primary mechanism of attenuation of bacillus Calmette-Guerin is a loss of secreted lytic function required for invasion of lung interstitial tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12420–12425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1635213100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys IR, Stewart GR, Turner DJ, Patel J, Karamanou D, Snelgrove RJ, Young DB. A role for dendritic cells in the dissemination of mycobacterial infection. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:1339–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krutzik SR, Modlin RL. The role of Toll-like receptors in combating mycobacteria. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson ND, Weinstein BM. In vivo imaging of embryonic vascular development using transgenic zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2002;248:307–318. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarevic V, Nolt D, Flynn JL. Long-term control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection is mediated by dynamic immune responses. J Immunol. 2005;175:1107–1117. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.2.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leemans JC, Juffermans NP, Florquin S, van Rooijen N, Vervoordeldonk MJ, Verbon A, van Deventer SJ, van der Poll T. Depletion of alveolar macrophages exerts protective effects in pulmonary tuberculosis in mice. J Immunol. 2001;166:4604–4611. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leemans JC, Thepen T, Weijer S, Florquin S, van Rooijen N, van de Winkel JG, van der Poll T. Macrophages play a dual role during pulmonary tuberculosis in mice. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:65–74. doi: 10.1086/426395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowery LA, Sive H. Initial formation of zebrafish brain ventricles occurs independently of circulation and requires the nagie oko and snakehead/atp1a1a.1 gene products. Development. 2005;132:2057–2067. doi: 10.1242/dev.01791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie MB, Abramson S, Heppleston AG. On the response of genetically resistant and susceptible rabbits to the quantitative inhalation of human type tubercle bacilli and the nature of resistance to tuberculosis. J Exp Med. 1952;95:119–134. doi: 10.1084/jem.95.2.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackaness GB. The influence of immunologically committed lymphoid cells on macrophage activity in vivo. J Exp Med. 1969;129:973–992. doi: 10.1084/jem.129.5.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathias JR, Perrin BJ, Liu TX, Kanki J, Look AT, Huttenlocher A. Resolution of inflammation by retrograde chemotaxis of neutrophils in transgenic zebrafish. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:1281–1288. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0506346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough KA, Kress Y, Bloom BR. The interaction of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with macrophages: a study of phagolysosome fusion. Infect Agents Dis. 1993;2:232–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurray DN. Hematogenous reseeding of the lung in low-dose, aerosol-infected guinea pigs: unique features of the host-pathogen interface in secondary tubercles. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2003;83:131–134. doi: 10.1016/s1472-9792(02)00079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller-Ortiz SL, Wanger AR, Norris SJ. Mycobacterial protein HbhA binds human complement component C3. Infect Immun. 2001;69:7501–7511. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7501-7511.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murayama E, Kissa K, Zapata A, Mordelet E, Briolat V, Lin HF, Handin RI, Herbomel P. Tracing Hematopoietic Precursor Migration to Successive Hematopoietic Organs during Zebrafish Development. Immunity. 2006;25:963–975. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrvik QN, Leake ES, Wright MJ. Disruption of phagosomal membranes of normal alveolar macrophages by the H37Rv strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. A correlate of virulence. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;129:322–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasevicius A, Ekker SC. Effective targeted gene ‘knockdown’ in zebrafish. Nat Genet. 2000;26:216–220. doi: 10.1038/79951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuenhahn M, Kerksiek KM, Nauerth M, Suhre MH, Schiemann M, Gebhardt FE, Stemberger C, Panthel K, Schroder S, Chakraborty T, et al. CD8alpha+ dendritic cells are required for efficient entry of Listeria monocytogenes into the spleen. Immunity. 2006;25:619–630. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North RJ, Jung YJ. Immunity to tuberculosis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:599–623. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H, Yan BS, Rojas M, Shebzukhov YV, Zhou H, Kobzik L, Higgins DE, Daly MJ, Bloom BR, Kramnik I. Ipr1 gene mediates innate immunity to tuberculosis. Nature. 2005;434:767–772. doi: 10.1038/nature03419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozos TC, Ramakrishnan L. New models for the study of Mycobacterium-host interactions. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16:499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pressley ME, Phelan PE, 3rd, Witten PE, Mellon MT, Kim CH. Pathogenesis and inflammatory response to Edwardsiella tarda infection in the zebrafish. Dev Comp Immunol. 2005;29:501–513. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renshaw SA, Loynes CA, Trushell DM, Elworthy S, Ingham PW, Whyte MK. A transgenic zebrafish model of neutrophilic inflammation. Blood. 2006;108:3976–3978. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes J, Hagen A, Hsu K, Deng M, Liu TX, Look AT, Kanki JP. Interplay of pu.1 and gata1 determines myelo-erythroid progenitor cell fate in zebrafish. Dev Cell. 2005;8:97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rook GA, Steele J, Ainsworth M, Leveton C. A direct effect of glucocorticoid hormones on the ability of human and murine macrophages to control the growth of M. tuberculosis. Eur J Respir Dis. 1987;71:286–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DG. Mycobacterium and Leishmania: stowaways in the endosomal network. Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:125–128. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)88963-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorey JS, Carroll MC, Brown EJ. A macrophage invasion mechanism of pathogenic mycobacteria. Science. 1997;277:1091–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5329.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott EW, Simon MC, Anastasi J, Singh H. Requirement of transcription factor PU.1 in the development of multiple hematopoietic lineages. Science. 1994;265:1573–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.8079170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraj P, Narayanan PR, Reetha AM. Association of functional mutant homozygotes of the mannose binding protein gene with susceptibility to pulmonary tuberculosis in India. Tuber Lung Dis. 1999;79:221–227. doi: 10.1054/tuld.1999.0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamm LM, Morisaki JH, Gao LY, Jeng RL, McDonald KL, Roth R, Takeshita S, Heuser J, Welch MD, Brown EJ. Mycobacterium marinum escapes from phagosomes and is propelled by actin-based motility. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1361–1368. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stead WW. Variation in vulnerability to tuberculosis in America today: random, or legacies of different ancestral epidemics? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5:807–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaim LE, Connolly LE, Volkman HE, Humbert O, Born DE, Ramakrishnan L. Mycobacterium marinum infection of adult zebrafish causes caseating granulomatous tuberculosis and is moderated by adaptive immunity. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6108–6117. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00887-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan BH, Meinken C, Bastian M, Bruns H, Legaspi A, Ochoa MT, Krutzik SR, Bloom BR, Ganz T, Modlin RL, Stenger S. Macrophages acquire neutrophil granules for antimicrobial activity against intracellular pathogens. J Immunol. 2006;177:1864–1871. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traver D, Herbomel P, Patton EE, Murphey RD, Yoder JA, Litman GW, Catic A, Amemiya CT, Zon LI, Trede NS. The zebrafish as a model organism to study development of the immune system. Adv Immunol. 2003;81:253–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trede NS, Medenbach J, Damianov A, Hung LH, Weber GJ, Paw BH, Zhou Y, Hersey C, Zapata A, Keefe M, et al. Network of coregulated spliceosome components revealed by zebrafish mutant in recycling factor p110. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6608–6613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701919104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkman HE, Clay H, Beery D, Chang JC, Sherman DR, Ramakrishnan L. Tuberculous granuloma formation is enhanced by a mycobacterium virulence determinant. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waskiewicz AJ, Rikhof HA, Moens CB. Eliminating zebrafish pbx proteins reveals a hindbrain ground state. Dev Cell. 2002;3:723–733. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00319-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson RJ, Patel P, Llewelyn M, Hirsch CS, Pasvol G, Snounou G, Davidson RN, Toossi Z. Influence of polymorphism in the genes for the interleukin (IL)-1 receptor antagonist and IL-1beta on tuberculosis. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1863–1874. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.12.1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worley MJ, Nieman GS, Geddes K, Heffron F. Salmonella typhimurium disseminates within its host by manipulating the motility of infected cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17915–17920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604054103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.