Summary

The T cell immunoglobulin mucin (TIM) proteins are a family of cell surface phosphatidyserine receptors that are important for the recognition and phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. Because TIM-4 is expressed by macrophages and dendritic cells in human tissue, we examined its expression in a range of histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms and found moderate to strong immunohistochemical staining in cases of juvenile xanthogranuloma and histiocytic sarcoma, and lower level staining in interdigitating dendritic cell sarcoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, acute monocytic leukemia (leukemia cutis), and blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (hematodermic tumor). TIM-3 was first described on activated TH1 cells but was recently shown to also be a phosphatidylserine receptor and mediate phagocytosis. We found TIM-3 was expressed by peritoneal macrophages, monocytes and splenic dendritic cells. We found that it, like TIM-4, is expressed in a range of histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms, typically with strong immunohistochemical staining. Cases of diffuse large B cell lymphoma, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, metastatic malignant melanoma, and metastatic poorly differentiated carcinoma generally exhibited negative to minimal heterogenous staining for TIM-4 and TIM-3. We conclude that histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms consistently express TIM-3 and TIM-4 and that these molecules are new markers of neoplasms derived from histiocytic and dendritic cells.

Keywords: Interdigitating dendritic cell sarcoma, Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma, Juvenile xanthogranuloma, Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm, Leukemia cutis, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, T cell immunoglobulin mucin protein

1. Introduction

The T cell immunoglobulin mucin (TIM) proteins are cell surface glycoproteins that regulate T cell activation and tolerance (reviewed in ref. [1]). Recently, we reported that TIM-4, expressed on human and mouse macrophages and dendritic cells, specifically binds to phosphatidylserine (PS) on the surface of apoptotic cells and is critical for the efficient clearance of these cells and prevention of autoimmunity [2]. TIM-4 is expressed on macrophages in both human and mouse, including tingible-body macrophages in germinal centers of lymphoid tissues and on interfollicular dendritic cells in lymphoid tissues but not on human peripheral blood monocytes [2]. Other members of the TIM protein family in humans include TIM-1 and TIM-3, which are expressed on T cells [1]. TIM-1 expression has been reported on activated T cells, including TH2 cells, and is thought to act as a T cell costimulatory molecule for the TH2 immune response to extracellular pathogens. TIM-3 is expressed on TH1 cells and cytotoxic T cells as well as on some “exhausted” T cells and is thought to have a down regulatory effect on the TH1 immune response to intracellular pathogens [1,3].

Recently, Nakayama et al and DeKruyff et al reported that TIM-3 is also a PS receptor involved in phagocytosis of apoptotic cells [4,5]. The former group also found that although TIM-4 is expressed at high levels in mouse peritoneal resident macrophages, TIM-3 is expressed at high levels in peritoneal exudate macrophages and also on peripheral blood monocytes and splenic dendritic cells. Neither TIM-1 or TIM-2 were found to be expressed on peritoneal macrophages [4]. In addition, Anderson et al. have reported moderate levels of TIM-3 expression on human peripheral blood dendritic cells and low levels on blood monocytes [6].

Based on these recent studies, we performed immunohistochemical staining experiments to study the expression of TIM-4 and TIM-3 in normal human tissues, to assess staining of histiocytes and dendritic cells. We then examined a range of histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms for TIM-4 and TIM-3 expression, to determine whether these molecules are expressed by neoplastic cells and whether they might serve as useful markers for neoplasms of histiocytic and dendritic cell origin.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Case selection

Cases were obtained from the files of the Department of Pathology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, with the institutional internal review boards’ approval. The pathologic diagnoses were originally established according to the criteria of the 2008 World Health Organization classification using morphology and immunohistochemical staining [7]. Diagnostic slides from all cases were reviewed by the authors of this study (D.M.D., J.L.H.).

2.2. Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 5-µm-thick formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues sections using a standard indirect avidin-biotin horseradish peroxidase method and diaminobenzidine color development, as previously described [8]. Two color immunostaining was performed as previously described [9], using Permanent Red (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) as a reagent for color development, in addition to diaminobenzidine. Briefly, slides were soaked in xylene, passed through graded alcohols and put in distilled water. The sections were blocked for peroxidase activity with 3% hydrogen peroxide in ethanol for 15 minutes and washed under the running water for 5 minutes. Slides were then pretreated with 1 mmol/L EDTA buffer pH 8.0 (for TIM-3 staining) and 10 mmol/L citrate, pH 6.0 (for TIM-4, CD68, and Langerin staining) in a microwave (800 W, General Electric, Louisville, KY) at 199°F for 30 minutes in preheated buffer, followed by washing in distilled water. All further steps were performed at room temperature in a hydrated chamber.

Immunostaining with goat anti-human TIM-4 polyclonal antibody and goat anti-human TIM-3 polyclonal antibody (R and D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was compared with that of goat IgG control antibody diluted to identical protein concentration for all cases studied, to confirm staining specificity. Immunostaining for CD68 and Langerin was performed using mouse monoclonal antibodies obtained from Novocastra Laboratories, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK.

2.3. Case evaluation

Reactivity for TIM-4 and TIM-3 was considered positive if >25% of the neoplastic cells exhibited staining. Neoplastic cells were further characterized as exhibiting low (1+), moderate (2+), or high (3+) level staining.

Photomicrographs of select cases were generated on an Olympus BX41 microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) using an Olympus Q-color5 digital camera and analyzed with the software Adobe Photoshop Elements 2.0 (Adobe, San Jose, CA).

3. Results

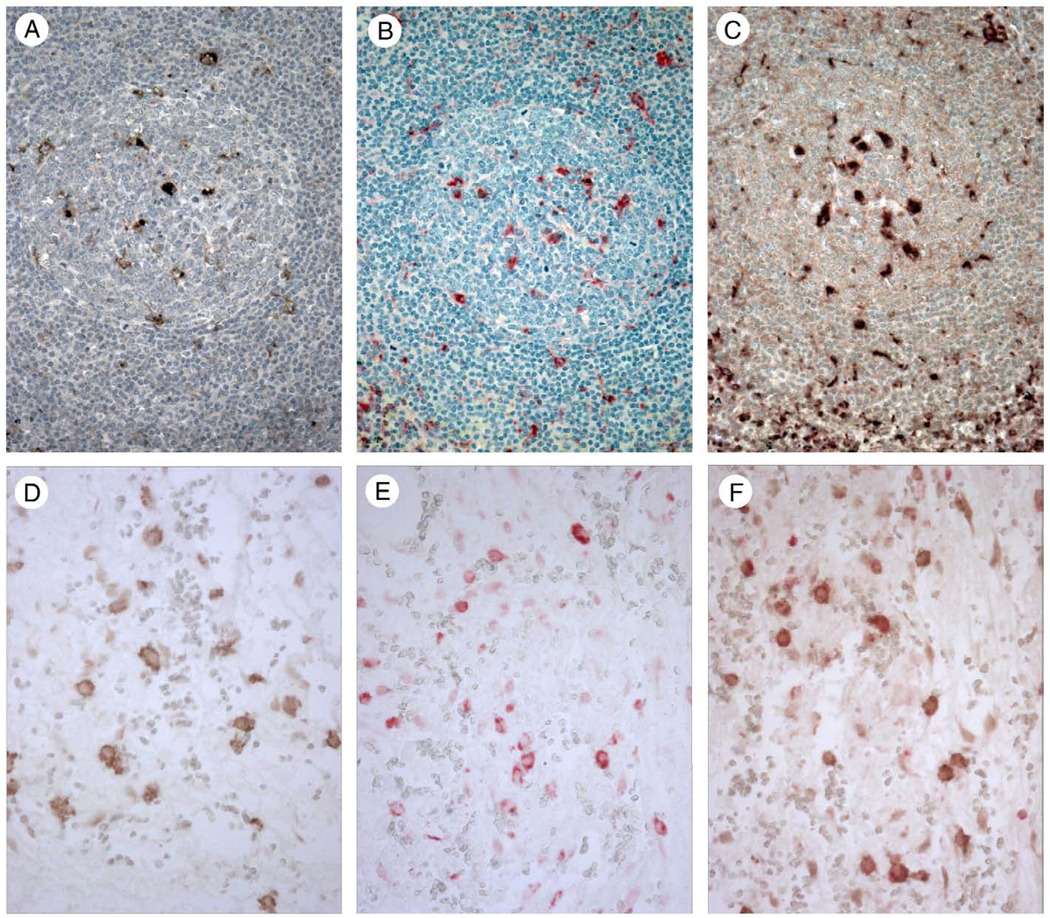

Immunohistochemical staining of tonsil and spleen with goat anti-human TIM-4 polyclonal antibody showed staining of tingible-body macrophages in germinal centers of tonsil (Fig. 1A) and white pulp of spleen as well as interfollicular dendritic cells (not shown). Since tingible bodies are the remnants of phagocytosed cells, these results are consistent with TIM-4 recognition of PS exposed on the surface of apoptotic cells. In 2-color immunohistochemical staining experiments using antibodies for TIM-4 and CD68, a marker of cells with monocyte/macrophage differentiation, germinal center tingible body macrophages in tonsil and splenic white pulp exhibited dual staining for TIM-4 and CD68 (Fig. 1C). No staining of tingible-body macrophages or dendritic cells was observed with control goat IgG (not shown). Previously we showed that TIM-4 staining of macrophages and dendritic cells was lost after TIM-4 antibody was adsorbed on TIM-4 transfected 300.19 cells but not following adsorption on non-transfected 300.19 cells [2].

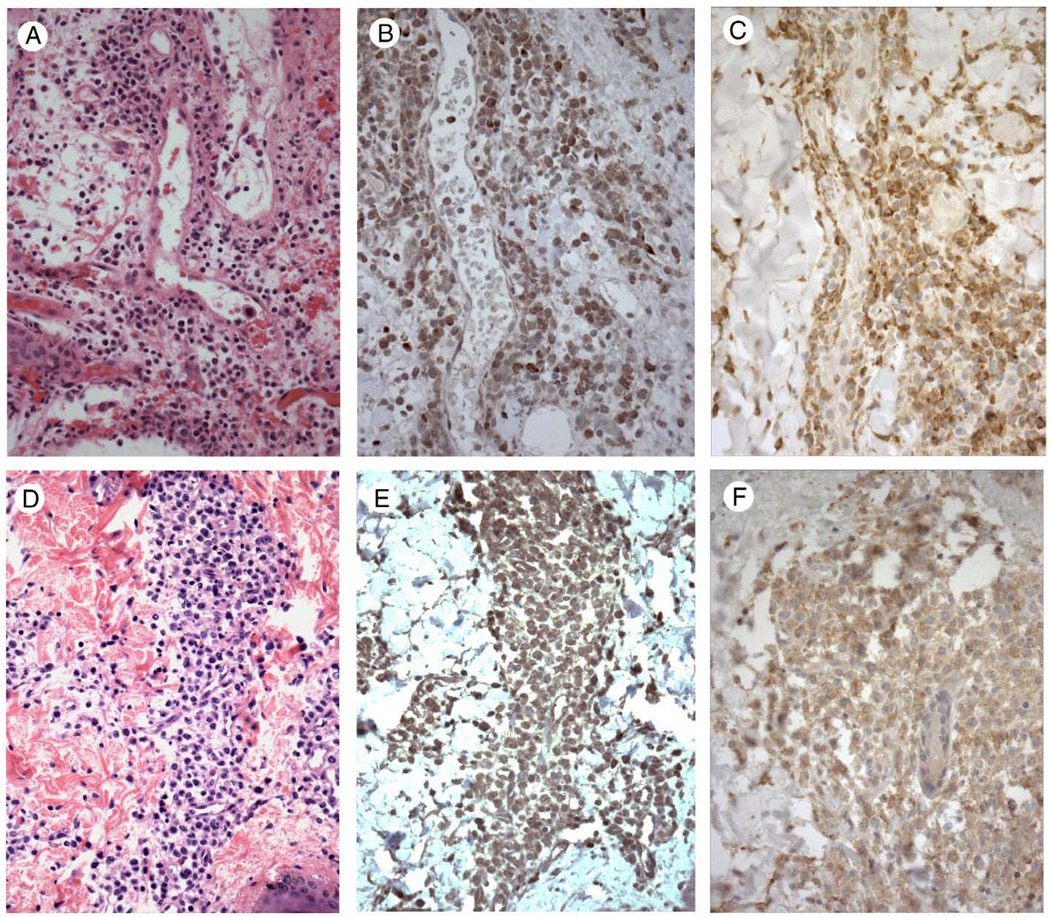

Figure 1.

Human tonsil (A–C) stained with specific antibodies recognizing TIM-4 (A and C) and CD68 (B and C) shows positive staining for TIM-4 in tingible body macrophages in germinal centers (A) as well as in interfollicular dendritic cells (not shown). Tingible body macrophages show positive staining with CD68 (B) and coexpression of TIM-4 and CD68 in double staining experiments (C). Peritoneal tissue (D–F) stained with specific antibodies recognizing TIM-3 (D and F) and CD68 (E and F) shows positive staining for TIM-3 in peritoneal macrophages (D). Peritoneal macrophages show positive staining with CD68 (E) and coexpression of TIM-3 and CD68 in double staining experiments (F). Magnification × 400.

We examined human peritoneal tissue for expression of TIM-3 and found staining in a subset of CD68-positive peritoneal macrophages (Fig. 1D and E). We also observed TIM-4 staining in a subset of CD68-positive peritoneal macrophages (not shown). In 2-color immunohistochemical staining experiments using antibodies for TIM-3 and CD68, TIM-3-positive peritoneal macrophages exhibited dual staining for TIM-3 and CD68 (Fig. 1F).

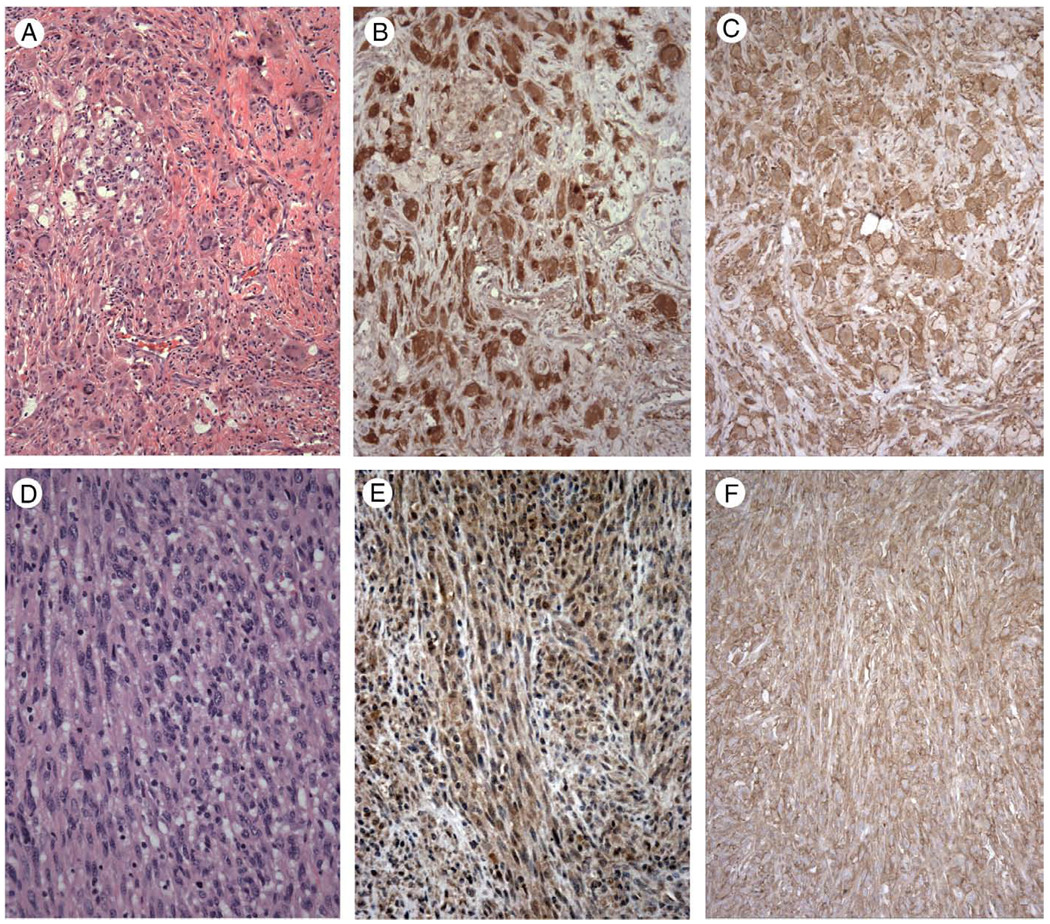

We next examined a range of human neoplasms with histiocytic and dendritic cell differentiation; the results are summarized in Table 1. Strong positive immunostaining for TIM-4 was observed in all 4 cases of juvenile xanthogranuloma examined, with strong cytoplasmic staining of xanthomatous, Touton-type giant cells, and more moderate cytoplasmic staining of smaller epithelioid cells and spindle cells (Fig. 2A and B). Three of the 4 cases of juvenile xanthogranuloma were stained for TIM-3 and exhibited strong positive staining, with accentuated membrane staining observed for TIM-3 but not TIM-4 (Fig. 2C).

Table 1.

TIM-3 and TIM-4 immunoreactivity in histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms

| TIM-4 | TIM-3 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1+ | 2+ | 3+ | 0 | 1+ | 2+ | 3+ | |||

| Juvenile xanthogranuloma | 4/4 (100%)a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3/3 (100%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Histiocytic sarcoma | 11/11 (100%) | 0 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 6/6 (100%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Interdigitating dendritic cell sarcoma | 6/6 (100%) | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 3/3 (100%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma | 1/4 (25%) | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1/4 (25%) | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Langerhans cell histiocytosis | 8/8 (100%) | 0 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 6/6 (100%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Acute monocytic leukemia (leukemia cutis) | 6/6 (100%) | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 6/6 (100%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Hematodermic tumor | 5/5 (100%) | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5/5 (100%) | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

Positive cases/total cases (%).

Figure 2.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (A, hematoxylin and eosin staining) shows strong cytoplasmic positive staining for TIM-4 (B) and TIM-3 (C), with accentuated membrane staining noted for TIM-3. Interdigitating dendritic cell sarcoma (D, hematoxylin and eosin staining) demonstrates weak to moderate cytoplasmic staining for TIM-4 (E) and strong cytoplasmic and membrane staining for TIM-3 (F). Magnification: A–C, × 200; D–F, × 400.

Six cases of interdigitating dendritic cell (IDC) sarcoma exhibited weak to moderate cytoplasmic staining for TIM-4 in all cases examined (Fig. 2D). In contrast, 3 of the 6 cases of IDC sarcoma were stained for TIM-3 and exhibited strong membrane and cytoplasmic staining (Fig. 2F). Cases of follicular dendritic cell (FDC) sarcoma were generally negative for TIM-4, except for 1 of 4 cases, which exhibited weak cytoplasmic staining (not shown). Similarly, 3 of the 4 cases of FDC sarcoma were negative for TIM-3, except for the one TIM-4–positive case, which exhibited moderate granular cytoplasmic staining for TIM-3 (not shown). This case was a CD21-positive, CD35-positive, cytokeratin-negative, S100-negative right supraclavicular fossa soft tissue mass from a 48-year-old man.

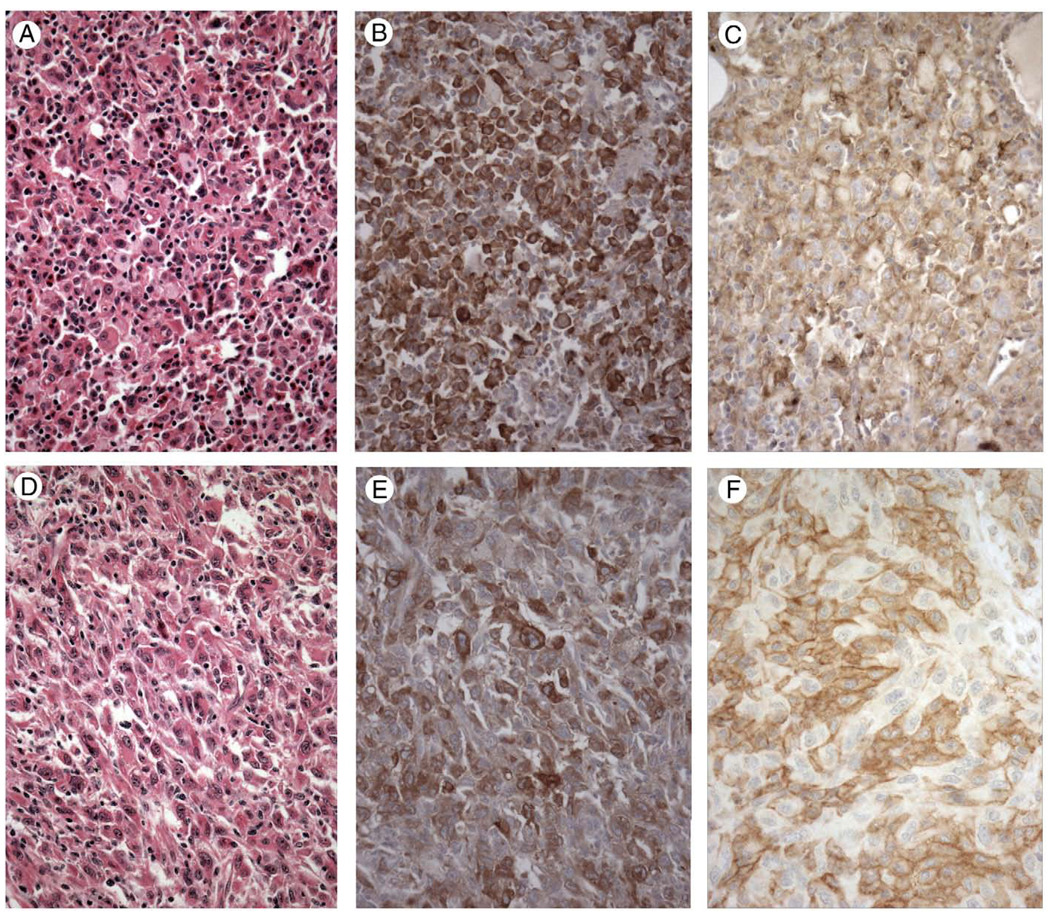

Cases of histiocytic sarcoma were found to exhibit positive immunostaining for TIM-4 in all 11 cases examined, ranging from low-level (1 case), to moderate (5 cases) to strong staining (5 cases). Staining was cytoplasmic and heterogeneous, in general, with staining greatest in large round to oval cells and with a subset of cases exhibiting granular cytoplasmic staining (Fig. 3B and E). Areas with spindle cell morphology exhibited weak to negative staining for TIM-4 (not shown). Six of the 11 cases of histiocytic sarcoma were stained for TIM-3 and exhibited strong cytoplasmic and membrane staining (5 cases; Fig. 3C and F) or strong cytoplasmic staining (1 case).

Figure 3.

Two cases of histiocytic sarcoma (A and D, hematoxylin and eosin staining) showing strong cytoplasmic staining for TIM-4 (B and E). Other cases exhibited weak to strong staining for TIM-4. All cases of histiocytic sarcoma tested exhibited strong cytoplasmic staining for TIM-3 (C) or strong cytoplasmic and membrane staining for TIM-3 (F). Magnification × 400.

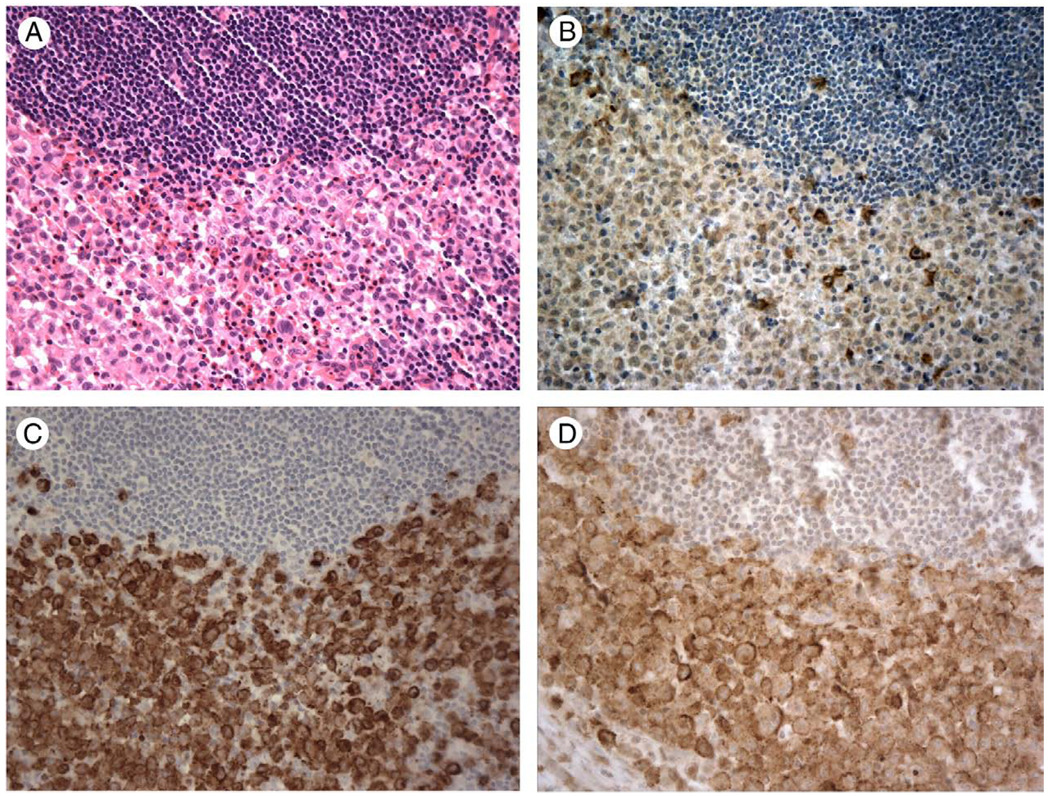

All 8 cases of Langerhans cell histiocytosis stained for TIM-4 exhibited uniform weak to moderate cytoplasmic staining for TIM-4 (Fig. 4B), with staining intensity less than that observed for Langerin (Fig. 4C), which was uniformly strongly positive in all 8 cases. In contrast, 6 of the 8 cases were stained for TIM-3 and exhibited strong granular cytoplasmic staining with membrane staining seen in 4 of 6 cases (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

A case of Langerhans cell histiocytosis involving lymph node (A, hematoxylin and eosin staining), shows weak cytoplasmic staining for TIM-4 (B), strong staining for Langerin (C) and strong membrane and cytoplasmic staining for TIM-3 (D). Magnification × 400.

Six cases of acute monocytic leukemia (AML M5) with skin involvement (leukemia cutis) exhibited uniform weak to moderate cytoplasmic staining for TIM-4 (Fig. 5B), with uniform strong granular cytoplasmic staining observed for TIM-3 (Fig. 5C). Similarly, 5 cases of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (hematodermic tumor; Fig. 5D) exhibited uniform weak to moderate cytoplasmic staining for TIM-4 (Fig. 5E), with uniform moderate cytoplasmic staining observed for TIM-3 (Fig. 5F), including 2 cases that exhibited membrane staining.

Figure 5.

A case of acute monocytic leukemia involving skin (leukemia cutis) (A, hematoxylin and eosin staining) showing moderate cytoplasmic staining for TIM-4 (B) and strong cytoplasmic staining for TIM-3 (C). A case of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm involving skin (D, hematoxylin and eosin staining) showing moderate cytoplasmic staining for TIM-4 (E) and moderate cytoplasmic staining for TIM-3 (F). Magnification × 400.

We next stained a number of additional 7neoplasms that would be considered in the differential diagnosis of histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms, to ascertain the diagnostic utility of TIM-4 and TIM-3. Thirteen cases of large cell lymphoma, including 9 cases of diffuse large B cell lymphoma and 4 cases of anaplastic large cell lymphoma, did not exhibit immunoreactivity for TIM-4 or TIM-3 (data not shown). Thirteen cases of metastatic malignant melanoma were studied, with 5 of 13 positive for TIM-4; 4 of 13 exhibited minimal (0–1+) staining (3 heterogeneous and 1 homogeneous) and 1 of 13 exhibited low (1+) homogeneous staining (data not shown). One of the 13 cases was negative for TIM-3, 5 of 13 exhibited minimal (0–1+) heterogenous staining, 4/13 exhibited low-level (1+) staining (3 heterogeneous, 1 homogeneous), 1/13 exhibited low to moderate (1–2+) heterogeneous staining, and 2 of 13 exhibited moderate (2+) heterogeneous staining (data not shown).

Thirteen cases of metastatic poorly differentiated carcinoma were examined for TIM-4 and TIM-3 staining. Staining for TIM-4 was negative in 7 of 13 cases, minimal (0–1+) and heterogenous in 4 of 13 cases, low level (1+) in 2 of 13 cases (1 heterogeneous, 1 homogeneous; data not shown). Staining for TIM-3 was negative in 2 of 13 cases, minimal (0–1+) and heterogeneous in 2/13 cases, low level (1+) in 3 of 13 cases (2 heterogeneous, 1 homogeneous), and low to moderate (1–2+) in 5 of 13 cases (4 heterogenous, 1 homogeneous; data not shown).

4. Discussion

Histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms are rare, and most are thought to be derived from a common myeloid stem cell, which can differentiate into 3 lines of histiocytic and dendritic cells. One lineage differentiates into monocytes and subsequently into interstitial dendritic cells and macrophages or histiocytes, 1 into Langerhans’ dendritic cells and interdigitating dendritic cells, and 1 into plasmacytoid dendritic cells [6,10,11]. In contrast, follicular dendritic cells are thought to be separately derived from bone marrow stromal progenitor cells and to be closely related to myofibroblastic cells [12].

A number of immunophenotypic markers are specific for terminally differentiated histiocytic and dendritic cells, reflecting their common origin, whereas others are expressed in a subset of these cell types, [6,10,11]. Similarly, neoplasms of histiocytic and dendritic cell origin express a number of overlapping immunophenotypic markers, such as CD68, fascin, and S100, as well as a number of more cell type-specific and neoplasm-specific markers, such as CD1a and Langerin in Langerhans cell histiocytosis and CD21 and CD35 in FDC sarcoma [7]. However, on further examination, a number of relatively specific markers of histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms may stain greater than 1 tumor type. For example, a recent study of Langerin (CD207), a type II transmembrane C-type lectin associated with the formation of Birbeck granules in Langerhans cells and thought to be a specific marker of Langerhans cell histiocytosis, found it to be expressed in a subset of cases of histocytic sarcoma as well [13]. A subset of histiocytic sarcomas have also been reported to express Langerhans cell markers CD1a and S100 [14], and, more recently, podoplanin (D2-40), a marker of follicular dendritic cells and follicular dendritic cell tumors [15].

We recently identified T cell immunoglobulin mucin protein family member TIM-4 as a marker of macrophages, including peritoneal and tingible body macrophages, and dendritic cells in humans and mice involved in the efficient clearance of apoptotic cells and prevention of autoimmunity [2]. Subsequently, TIM-3 was found to be expressed on mouse peritoneal macrophages, monocytes, and splenic dendritic cells and to mediate phagocytosis of apoptotic cells [4,5]. Here we have shown that human macrophages and dendritic cells in tonsil and spleen express TIM-4 and that peritoneal macrophages express TIM-3. We hypothesized that these proteins would also be expressed on histocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms.

We found TIM-4 expression on the vast majority of histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms including histiocytic sarcoma, IDC sarcoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, acute monocytic leukemia, and blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm, as assessed with immunohistochemical staining, generally with low to moderate levels of cytoplasmic staining. Juvenile xanthogranuloma exhibits high level staining for TIM-4. Similarly, TIM-3 was expressed on the vast majority of histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms, with generally high level cytoplasmic and membrane staining. Of note, FDC sarcomas are typically negative for TIM-4 and TIM-3 expression, likely a reflection of their separate origin from bone marrow stromal progenitor cells rather than myeloid stem cells [12]. The majority of neoplasms in the differential diagnosis of histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms, including large cell lymphomas, metastatic malignant melanoma, and metastatic poorly differentiated carcinoma were negative for TIM-4 and TIM-3 immunostaining or showed minimal or low level heterogenous staining for these markers. These results suggest that TIM-3 and TIM-4 may be diagnostically useful new markers of neoplasms derived from histiocytic and dendritic cells.

TIM-4 expression on normal cells is particularly restricted to macrophages and dendritic cells and is not seen on T or B lymphocytes [2]. TIM-3, in addition to its expression on macrophages and dendritic cells, was previously found to be expressed on some T cell subsets, specifically TH1 cells and cytotoxic T cells, and is thought to down-regulate TH1 immune responses to intracellular pathogens [1,16]. This suggests that expression of TIM-4 would be the more definitive marker in the differential diagnosis of histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms.

The expression of TIM-3 on macrophages, dendritic cells, and T cells as well as in histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms and, in addition, T cell lymphoproliferative disorders (D.M.D., unpublished data) may reflect a common origin of these cells and their neoplastic counterparts from a hematopoietic progenitor cell. Evidence for this hypothesis includes the identification of mouse bone marrow progenitor cells with the potential to differentiate into B cells and macrophages [17], as well as the presence of B cell/myeloid progenitor cells in normal human bone marrow [18]. Recently, Feldman and coworkers found cases of follicular lymphoma and histiocytic and IDC sarcomas that were clonally related, suggesting a common clonal origin, and plasticity between B cell and myeloid lineages [19]. Cases of histiocytic sarcoma and acute lymphoblastic leukemia and of Langerhans cell histiocytosis and B cell lymphoma with a common clonal origin have been described [20,21]. B cells have been shown to trans-differentiate into macrophages and to dedifferentiate to uncommitted precursor cells and subsequently differentiate into T cells, based on gain or loss of expression of transcription factors C/EBP α and β and PAX5, respectively [22,23]. Myeloid cells have been shown to differentiate into dendritic cells with alpha interferon treatment [24]. Other studies have demonstrated B cell-associated transcription factor expression in T cell neoplasms as well as the converse [25,26]. These studies provide evidence for a degree of phenotypic plasticity among hematopoietic and other cells that share a common precursor which may persist after neoplastic transformation.

Our results show that histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms consistently express TIM-3 and TIM-4, and that these molecules are new markers of neoplasms derived from histiocytic and dendritic cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH P01 AI054456 (G.F.).

References

- 1.Rodriguez-Manzanet R, DeKruyff R, Kuchroo VK, Umetsu DT. The costimulatory role of TIM molecules. Immunol Rev. 2009;229:259–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00772.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kobayashi N, Karisola P, Pena-Cruz V, et al. TIM-1 and TIM-4 glycoproteins bind phosphatidylserine and mediate uptake of apoptotic cells. Immunity. 2007;27:927–940. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Golden-Mason L, Palmer BE, Kassam N, et al. Negative immune regulator Tim-3 is overexpressed on T cells in hepatitis C virus infection and its blockade rescues dysfunctional CD4+ and CD8+T cells. J Virol. 2009;83(18):9122–9130. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00639-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakayama M, AKiba H, Takeda K, et al. Tim-3 mediates phagocytosis of apoptotic cells and cross-presentation. Blood. 2009;113:3821–3830. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-185884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeKruyff RH, Bu X, Ballesteros A, et al. TIM-3 allelic variants differentially recognize phosphatidylserine and mediate phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:1918–1930. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson AC, Anderson DE, Bregoli L, et al. Promotion of tissue inflammation by the immune receptor Tim-3 expressed on innate immune cells. Science. 2007;318(5853):1141–1143. doi: 10.1126/science.1148536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. Lyon: IARC Press; 2008. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorfman DM, Greisman HA, Shahsafaei A. Loss of expression of the WNT/beta-catenin-signaling pathway transcription factors lymphoid enhancer factor-1 (LEF-1) and T cell factor (TCF-1) in a subset of peripheral T cell lymphomas. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1539–1544. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64287-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorfman DM, Brown JA, Shahsafaei A, Freeman GJ. Programmed death-1 (PD-1) is a marker of germinal center-associated T cell and angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:802–810. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000209855.28282.ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weitzman S, Jaffe R. Uncommon histiocytic disorders: the non-Langerhans cell histiocytoses. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45:256–264. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mills JA, Gonzalez G, Jaffe R. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital (Case 25–2008: a 43-year-old man with fatigue and lesion sin the pituitary and cerebellum. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:736–747. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc0804623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munoz-Fernandez R, Blanco FJ, Frecha C, et al. Follicular dendritic cells are related to bone marrow stromal cell progenitors and to myofibroblasts. J Immunol. 2006;177:280–289. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lau SK, Chu PG, Weiss LM. Immunohistochemical expression of Langerin in Langerhans cell histiocytosis and non-Langerhans cell histiocytic disorders. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:615–619. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31815b212b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hornick JL, Jaffe ES, Fletcher CDM. Extranodal histiocytic sarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 14 cases of a rare epithelioid malignancy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1133–1144. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000131541.95394.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu H, Gibson JA, Pinkus GS, Hornick JL. Podoplanin (D2-40) is a novel marker for follicular dendritic cell tumors. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:776–782. doi: 10.1309/7P8U659JBJCV6EEU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hastings WD, Anderson DE, Kassam N, et al. TIM-3 is expressed on activated human CD4+T cells and regulates TH1 and TH17 cytokines. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(9):2492–2501. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montecino-Rodriguez E, Leathers H, Dorshkind K. Bipotential B-macrophage progenitors are present in adult bone marrow. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:83–88. doi: 10.1038/83210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hou YH, Srour EF, Ramsey H, Dahl R, Broxmeyer HE, Hromas R. Identification of a human B-cell/myeloid common progenitor by the absence of CXCR4. Blood. 2005;105:3488–3492. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feldman AL, Arber DA, Pittaluga S, et al. Clonally related follicular lymphomas and histiocytic/dendritic cell sarcomas: evidence for transdifferentiation of the follicular lymphoma clone. Blood. 2008;111:5433–5439. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-124792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feldman AL, Minniti C, Santi M, Downing JR, Raffeld M, Jaffe ES. Histiocytic sarcoma after acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a common clonal origin. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:248–250. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01428-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magni M, Di Nicola M, Carlo-Stella C, et al. Identical gene rearrangement of immunoglobulin heavy chain gene in neoplastic Langerhans cells and B-lymphocytes: evidence for a common precursor. Leuk Res. 2002;26:1131–1133. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(02)00009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie H, Ye M, Feng R, Graf T. Stepwise reprogramming of B cell into macrophages. Cell. 2004;117:663–676. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00419-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colbaleda C, Jochum W, Busslinger M. Conversion of mature B cells into T cell by dedifferentiation to uncommitted progenitors. Nature. 2007;449:473–477. doi: 10.1038/nature06159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paquette RL, Hsu N, Said J, et al. Interferon-alpha induces dendritic cell differentiation of CML mononuclear cells in vitro and in vivo. Leukemia. 2002;16:1484–1489. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marafioti T, Ascani S, Pulford K, et al. Expression of B-lymphocyte-associated transcription factors in human T-cell neoplasms. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:861–871. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63882-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dorfman DM, Hwang ES, Shahsafaei A, Glimcher LH. T-bet, a T-cell-associated transcription factor, is expressed in a subset of B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:292–297. doi: 10.1309/AQQ2-DVM7-5DVY-0PWP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]