Abstract

This paper evaluates an experiment in which individuals in rural Malawi were randomly assigned monetary incentives to learn their HIV results after being tested. Distance to the HIV results centers was also randomly assigned. Without any incentive, 34 percent of the participants learned their HIV results. However, even the smallest incentive doubled that share. Using the randomly assigned incentives and distance from results centers as instruments for the knowledge of HIV status, sexually active HIV-positive individuals who learned their results are three times more likely to purchase condoms two months later than sexually active HIV-positive individuals who did not learn their results; however, HIV-positive individuals who learned their results purchase only two additional condoms than those who did not. There is no significant effect of learning HIV-negative status on the purchase of condoms.

Over the past two decades, the HIV/AIDS epidemic has afflicted millions of individuals in Africa. In the absence of significantly expanded prevention and treatment programs, the epidemic is expected to worsen in many other parts of the world. One intervention often suggested to alleviate the spread of the disease is HIV testing, and some have gone so far as to say that voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) is the “missing weapon in the battle against AIDS.”1 Under the assumption that HIV testing is an effective prevention strategy, many international organizations and governments have called for increased investments in counseling and testing, requiring large amounts of monetary and human resources (Global Business Coalition 2005; Know HIV AIDS 2005). For example, in South Africa, government expenditures on counseling and testing increased from $2.4 million in 2000 to $17.3 million in 2004, and in Mozambique, 55 percent of all HIV/AIDS program expenditures in 2000 were for HIV counseling and testing (H. Gayle Martin 2003). Some governments have even suggested implementing universal testing programs, sending nurses door to door.2

Underlying the emphasis on HIV testing for prevention—and the large-scale expenditures on testing—are two rarely challenged assumptions. First, many believe that knowledge of HIV status has positive effects on sexual behavior that prevent the spread of the disease. In particular, it is assumed that those diagnosed HIV-negative will protect themselves from infection and those diagnosed HIV-positive will take precautions to protect others. Second, many believe that it is difficult to get people to learn their HIV status, due primarily to psychological or social barriers, thus justifying expenditures on destigmatization and advertising campaigns.

In this paper, I evaluate a field experiment in rural Malawi designed to address these assumptions. I find that barriers to obtaining HIV test results can be easily overcome by offering small cash incentives or by reducing the distance needed to travel for the results. I also find that while receiving an HIV-positive diagnosis has a significant effect on the subsequent purchase of condoms, the overall magnitude of the effect is small. The results in this paper suggest that, relative to other available prevention strategies or targeting high-risk populations, door-to-door HIV testing may not be the most effective HIV prevention strategy, as measured by condom purchases.

Previous studies have attempted to measure the demand for learning HIV status, as well as the subsequent behavioral effects. Most studies have relied on self-reported behavior by asking individuals if they want to know their HIV status (e.g., John H. Day et al. 2003; Joseph de Graft–Johnson et al. 2005; Susan M. Laver 2001; Stanley P Yoder and Pricilla Matinga 2004) or asking about reported sexual behavior (e.g., The Voluntary HIV-1 Counseling and Testing Efficacy Study Group 2000; M. Kamenga et al. 1994; M. Temmerman et al. 1990; and Lance S. Weinhardt et al. 1999). Self-selection is also a serious limitation to evaluating the effects of learning HIV results. Most, if not all, studies use a sample of individuals who self-select into knowing their HIV status.3

The design of this experiment avoids the usual complications of selection and reporting bias because it randomized individual incentives to learn HIV status, randomized the location of VCT centers where HIV results were available, measured actual post-test attendance at centers to obtain results, and measured actual condom purchases subsequent to learning HIV status. The experimental design of this study is important because factors influencing the decision to learn HIV results are generally correlated with behavioral outcomes, potentially biasing the estimates of the impact of learning HIV results on the demand for safe sex.

In this study, respondents in rural Malawi were offered a free door-to-door HIV test and were given randomly assigned vouchers between zero and three dollars, redeemable upon obtaining their results at a nearby VCT center. The demand for HIV test results among those who received no monetary incentive was moderate, at 34 percent. However, monetary incentives were highly effective in increasing result-seeking behavior: on average, respondents who received any cash-value voucher were twice as likely to go to the VCT center to obtain their HIV test results as were individuals receiving no incentive. Although the average incentive was worth about a day’s wage, even the smallest amount, approximately one-tenth of a day’s wage, resulted in large attendance gains. The location of each HIV results center was also randomly placed to evaluate the impact of distance on VCT attendance: living over 1.5 kilometers from the VCT center reduced attendance by 6 percent.

Several months later, follow-up interviews were conducted and respondents were given the opportunity to purchase condoms. Using the random allocation of incentives and distance as exogenous instruments for learning HIV status, I find that receiving an HIV-positive diagnosis significantly increased the likelihood of purchasing condoms among those with a sexual partner. However, the total number of condoms purchased by HIV-positive individuals who knew their test results was small. On average, those with a sexual partner who learned they were HIV-positive purchased two more condoms than those HIV-positives who did not learn their results. Learning HIV results had no impact on condom purchases among those who were HIV-negative or those who were not sexually active.

This paper measures the impact of learning HIV results on sexual activity and condom purchases two months later. While there may be other prevention strategies that individuals undertake after learning their results that are not measured in this paper, the findings presented here suggest that door-to-door testing may not be as cost-effective as other prevention programs in averting new infections. There may be a role for HIV testing, however, if it is targeted at high-risk groups. In addition, the findings in this paper suggest that offering small rewards to encourage people to learn their results may be very effective, for example, in giving HIV-positive individuals access to treatment or in distributing antiretroviral therapy to pregnant women to prevent HIV transmission to their baby.

I. Project Design

A. Background on Malawi and Description of the Data

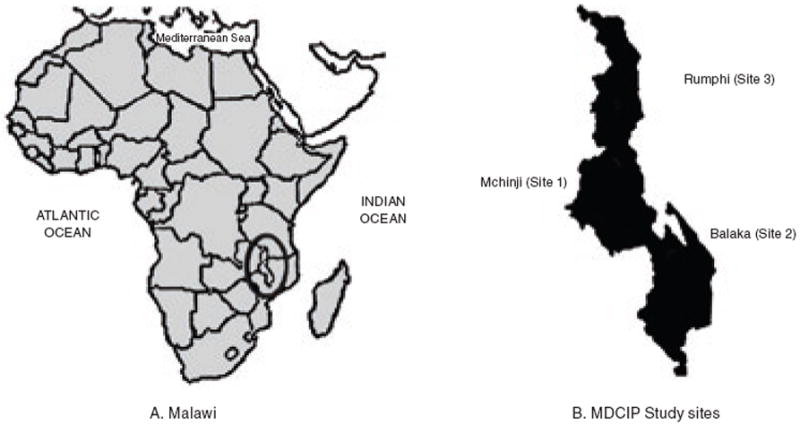

The Malawi Diffusion and Ideational Change Project (MDICP) is conducted in Malawi, a land-locked country located in southern Africa (Figure 1). This collaborative project between the University of Pennsylvania and the Malawi College of Medicine is an ongoing study of men and women randomly selected from approximately 120 villages in the districts of Rumphi, Mchinji, and Balaka, located in the Northern, Central, and Southern regions respectively.4 Approximately 25 percent of all households in each village were randomly selected to participate in 1998, and ever-married women and their husbands from these households were interviewed in 1998, 2001, and 2004. During data collection in 2004, an additional sample of young adults (ages 15–24) residing in the original villages was added to the sample.

Figure 1.

Malawi and MDICP Study Sites

Between May and August of 2004, nurses from outside each area offered respondents free tests in their homes for HIV and three other sexually transmitted infections (STIs): gonorrhea, chlamydia, and trichomoniasis. At the time that tests were offered, respondents were given pretest counseling about HIV prevention strategies. Samples were taken through oral swabs to test for HIV and through urine samples (for men) or self-administered vaginal swabs (for women) to test for other STIs (Simona Bignami–Van Assche et al. 2004 and Francis Obare et al. 2008 provide the full testing protocol.). Across the three districts, 2,894 of the 3,185 respondents who were offered accepted an HIV test (91 percent). The main sample in this paper consists of those who both accepted an HIV test and had basic covariate data: 2,812 individuals (Table 1, panel A). Sample attrition and test refusals are discussed below.

Table 1.

Sample Size and Determinants of Participation

| Panel A: Sample size and attrition | ||

| Percent of 1998 adult sample interviewed in 2001 | 0.78 | |

| Percent of 1998 adult sample interviewed in 2004 | 0.72 | |

| Main sample (accepted HIV test with co-variate data) | 2,812 | |

| Follow-up sample (main sample interviewed at follow-up) | 1,524 | |

| Percent accepting a test for HIV | 0.91 | |

| Percent of main sample (Balaka and Rumphi) interviewed at 2004 follow-up survey | 0.75 | |

|

| ||

| Panel B: Determinants of accepting an HIV test | (1) | (2) |

| Male | −0.004 (0.009) | −0.002 (0.008) |

| Age | 0.002 (0.003) | 0.003 (0.002) |

| Age-squared | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) |

| Married | −0.02 (0.017) | −0.030** (0.013) |

| Had a previous HIV test | 0.062*** (0.011) | 0.047*** (0.010) |

| Think treatment will become available | −0.012 (0.012) | |

| Think there is a likelihood of being HIV positive | −0.007 (0.010) | |

| Sample size | 3,141 | 2,682 |

| R2 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

|

| ||

| Panel C: Determinants of participation in the follow-up survey | (1) | |

| Got results | 0.240*** (0.022) | |

| Any incentive | 0.068 (0.044) | |

| Amount of incentive | −0.098* (0.056) | |

| Amount of incentive2 | 0.025 (0.017) | |

| Distance (km) | 0.013 (0.047) | |

| Distance2 | −0.007 (0.008) | |

| HIV positive | −0.171*** (0.044) | |

| Sample size | 2,021 | |

| R2 | 0.09 | |

Notes: Panel B represents one OLS regression of acceptance of an HIV test among those respondents offered a test. Panel C represents one OLS regression among respondents eligible for the follow-up survey (those tested for HIV in Balaka and Rumphi). Controls also include gender, age, and age-squared. Robust standard errors clustered by village with district fixed effects are in parentheses. “Any” is an indicator if the respondent received any nonzero monetary incentive and “amount” is the total value of the incentive.

Significantly different from zero at 99 percent confidence level.

Significantly different from zero at 95 percent confidence level.

Significantly different from zero at 90 percent confidence level.

The main sample is 46 percent male with an average age of 33 (Table 2, panel A). Seventy-one percent of the respondents were married at the time of the interview and 58 percent had ever attended school, with an average of almost four years. Ethnicity and religion vary across the three districts: the Chewas in Mchinji and the Tumbukas in Rumphi are primarily Christian; the Yaos in Balaka traditionally practice Islam. The majority of the respondents are subsistence farmers and 73 percent own land. The HIV prevalence rate was 6.3 percent (7.2 percent for females, 5.1 percent for males). Prevalence rates for other sexually transmitted diseases were even lower, with 3.2 percent men and women infected with gonorrhea, 0.3 percent men and women with chlamydia, and 2.4 percent women with trichomoniasis (Table 2, panel B). The prevalence of HIV in the MDICP sample is considerably lower than national prevalence rates. Another population-based study in Malawi found an overall HIV prevalence rate of 12.5 percent in 2004 (DHS 2004). Among the rural populations, however, the Malawi DHS found an HIV rate of 5.2 percent in the Northern region, 7.3 percent in the Central region, and 16.7 percent in the Southern region, which are comparable to the MDICP sample rates of 4.4 percent in the Northern region (Rumphi), 6.4 percent in the Central region (Mchinji), and 7.9 percent in the Southern region (Balaka). Longitudinal sample attrition from death and migration (discussed below) may also bias the estimates downward (Philip Anglewicz 2007), as well as the disproportionate number of young adults age 15–24 included in the sample (33.4 percent of respondents), who have a lower overall infection rate of 2.7 percent. See Section IC for further discussion.

Table 2.

Summary Statistics

| Full sample | Follow-up sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observations | 2,812 | 1,524 | ||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Panel A: Respondent characteristics | ||||

| Male | 0.46 | (0.50) | 0.46 | (0.50) |

| Age | 33.4 | (13.66) | 34.6 | (14.30) |

| Married | 0.71 | (0.45) | 0.72 | (0.45) |

| Years of education | 3.6 | (3.70) | 3.8 | (3.80) |

| Owns land | 0.73 | (0.44) | 0.74 | (0.44) |

|

| ||||

| Panel B: Health | ||||

| HIV positive | 0.063 | (0.24) | 0.048 | (0.21) |

| Gonorrhea positive | 0.032 | (0.18) | 0.034 | (0.18) |

| Chlamydia positive | 0.003 | (0.06) | 0.004 | (0.06) |

| Trichomoniasis positive | 0.024 | (0.15) | 0.014 | (0.12) |

| Ever had an HIV test (before 2004) | 0.181 | (0.385) | 0.217 | (0.412) |

| Thinks treatment will be available in five years | 0.341 | (0.474) | 0.372 | (0.484) |

| Reported having sex during 2004 | 0.761 | (0.43) | 0.759 | (0.43) |

| Reported using condoms during 2004 | 0.210 | (0.41) | 0.210 | (0.41) |

| Sexual acts in one month (if > 0) | 5.104 | (4.89) | 5.104 | (4.82) |

|

| ||||

| Panel C: Incentives, distance, and attendance at results centers | ||||

| Monetary incentive (dollars) | 1.01 | (0.90) | 1.05 | (0.91) |

| Distance to VCT center (km) | 2.02 | (1.27) | 2.20 | (1.34) |

| Attended VCT center | 0.69 | (0.46) | 0.72 | (0.45) |

| Attended VCT center (if incentive = 0) | 0.34 | (0.47) | 0.37 | (0.48) |

|

| ||||

| Panel D: Follow-up condom sales | ||||

| Purchased condoms at the follow-up | — | — | 0.24 | (0.43) |

| Number of condoms purchased (if > 0) | — | — | 3.66 | (2.18) |

| Reported purchasing condoms | — | — | 0.08 | (0.27) |

| Reported having sex after VCT | — | — | 0.62 | (0.49) |

| Reported having sex with more than one partner after VCT | — | — | 0.033 | (0.18) |

Notes: Full sample includes respondents who accepted a test for HIV in 2004 and have basic demographic data. Follow-up sample includes respondents in Balaka and Rumphi who tested and were reinterviewed in 2005. HIV prevalence rates do not include 14 respondents with indeterminate diagnoses. Other STI prevalence rates do not include 83 respondents with indeterminate diagnoses. Trichomoniasis was tested only among women. Respondents were asked about sexual acts per month only during the nurses’ survey in Balaka. The monetary incentive is a sum of an incentive for learning HIV results and an incentive for learning other STI results (in Mchinji and Balaka). Distance from assigned testing centers to respondents’ homes is a straight-line spherical distance measured in kilometers. Reported having sex with more than one partner does not include those who did not report having sex in the follow-up survey. Sexual acts per month was asked only among a subset of respondents between the baseline survey and time of the VCT.

B. Experimental Design

The first part of the experimental design involved offering monetary incentives to encourage respondents to obtain their test results at nearby centers. After taking the HIV test samples, nurses gave each respondent vouchers redeemable upon obtaining either HIV or STI results. Voucher amounts were randomized by letting each respondent draw a token out of a bag indicating a monetary amount. In Mchinji and Balaka each respondent received two vouchers, one for obtaining HIV results, and one for obtaining STI results. In Rumphi, respondents received only one voucher redeemable by returning for either HIV or STI results. For the analysis, I examine the impact of the total value of the incentive (the sum of the HIV and STI incentives) on obtaining results. In Mchinji and Balaka, all respondents learned both their HIV and STI results. Vouchers ranged between zero and three dollars, with an average total voucher amount (including zeros) of 1.01 dollars, worth approximately a day’s wage (Table 2, panel C).

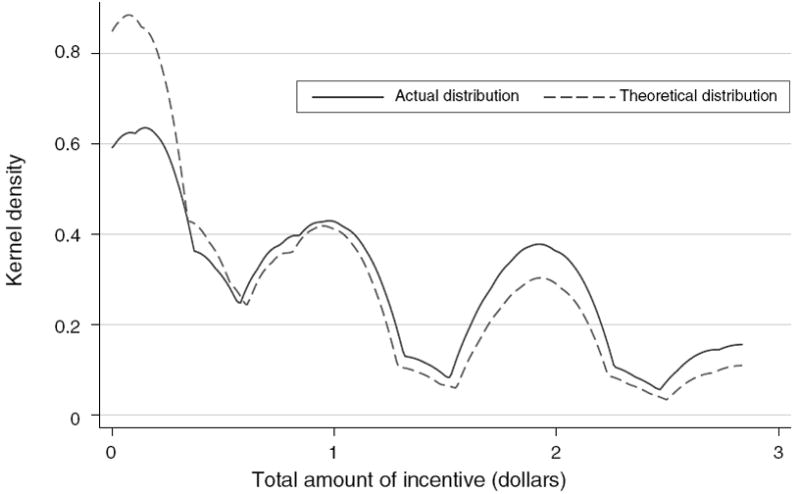

The distribution of vouchers was carefully monitored to ensure that each nurse followed the rules of randomization.5 Figure 2 presents the distribution of the vouchers. Each voucher included the amount, a respondent ID, and the nurse’s signature; a carbon copy was made to prevent forgeries. Respondents who drew a zero token received no voucher; 22 percent received no incentive to return for either HIV or STI results. Drawing a “zero” may have had a demotivating effect on individuals wanting to attend the VCT, center which may have had an impact on attendance. Because all of the respondents participated in the “lottery” draw, it is impossible to estimate the potential effect of disappointment. However, this is likely to be minimal.

Figure 2. Distribution of Incentives to Return for HIV Results ($).

Notes: Sample includes 2,812 individuals who tested for HIV and have age data. Figure presents the actual kernel density of the distribution of monetary incentives given by nurses and the theoretical distribution of the incentives to be given.

Two to four months after sample collection, test results became available, and temporary test results (VCT) centers, consisting of small portable tents, were placed randomly throughout the districts. Based on their geospatial (GPS) coordinates, respondents’ households in villages were grouped into zones, and a location within each zone was randomly selected to place a tent. The average distance to a center was two kilometers and over 95 percent of those tested lived within five kilometers. Distance to the VCT center is calculated as a straight line and does not account for roads or paths. In most cases, tents were placed in the exact randomly selected location and paths were created for easy accessibility.6 Baseline characteristics are similar across groups receiving any incentive amount (including zero) and living within various VCT zones. Although there are some statistically significant differences among these groups, they are small in magnitude (Table 3).

Table 3.

Baseline Characteristics by Incentives and Distance

| Dependent variable | Male (1) | Age (2) | HIV positive (3) | Years of education (4) | Owns land (5) | Had sex in 2004 (6) | Used a condom in 2004 (7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any incentive | −0.051 (0.039) | 2.034*** (0.993) | 0.001 (0.020) | −0.25 (0.284) | 0.018 (0.033) | −0.027 (0.033) | 0.006 (0.029) |

| Amount of incentive | 0.06 (0.055) | −0.185 (1.331) | −0.018 (0.024) | 0.022 (0.356) | 0.005 (0.043) | −0.029 (0.048) | −0.061 (0.045) |

| Amount of incentive2 | −0.015 (0.018) | −0.103 (0.435) | 0.005 (0.008) | 0.038 (0.116) | 0.002 (0.014) | 0.008 (0.015) | 0.022 (0.016) |

| Distance (km) | −0.025 (0.022) | −0.211 (1.133) | 0.026 (0.016) | −0.089 (0.330) | −0.045 (0.033) | 0.012 (0.028) | 0.041 (0.028) |

| Distance2 | 0.006 (0.004) | 0.096 (0.240) | 0.004 (0.003) | −0.015 (0.064) | 0.011 (0.007) | -0.001 (0.005) | −0.006 (0.005) |

| Constant | 0.487*** (0.030) | 30.585*** (1.217) | 0.101*** (0.023) | 3.311*** (0.366) | 0.768*** (0.036) | 0.791*** (0.037) | 0.167*** (0.036) |

| Sample size | 2,812 | 2,812 | 2,812 | 2,530 | 2,594 | 2,343 | 2,374 |

| R2 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

Notes: Sample includes individuals who tested for HIV and have demographic data. Columns represent OLS coefficients; robust standard errors clustered by village (for 119 villages) with district fixed effects in parentheses. “Any incentive” is an indicator if the respondent received any nonzero monetary incentive. “HIV” is an indicator of being HIV positive. Also includes age, age-squared, and gender. Distance is measured as a straight-line spherical distance from a respondent’s home to randomly assigned VCT center from geospatial coordinates and is measured in kilometers.

Significantly different from zero at 99 percent confidence level.

Significantly different from zero at 95 percent confidence level.

Significantly different from zero at 90 percent confidence level.

Respondents were personally informed of the hours of operation and location of their assigned center (open Monday through Saturday from 8 a.m. to 7 p.m.) and centers were operational for approximately one week. Respondents were allowed to attend any of the VCT centers but were informed only of the location and hours of operation of their assigned center (fewer than 6 percent of respondents went to a center other than the one to which they were assigned). When they obtained their test results, respondents also received counseling. On average, nurses spent 30 minutes counseling each respondent about safe sexual practices, including abstinence and condom use, regardless of respondent’s HIV test results. Several studies have shown that education can have an impact on condom use and HIV prevention (see Jeff Stryker et al. 1995; K. J. Sikkema et al. 2000). In this study, however, it is impossible to distinguish a pure information effect (learning HIV status) from an educational effect (counseling). The counseling received at the VCT centers would then produce upper bounds of the effects of learning HIV test results alone. Couples were given their test results verbally and were informed of their results separately. Respondents could redeem their vouchers only after hearing their results. Those who were HIV-positive were referred to the nearest permanent clinic for further counseling. Those who were positive for other sexually transmitted diseases were also given free treatment at that time, which may have provided additional incentive to attend VCT centers, over and above the monetary incentive. However, STI prevalence rates were very low (see Table 2, panel B).

Approximately two months after results were available, respondents who tested for HIV in two districts, Balaka and Rumphi, were reinterviewed in their homes by interviewers who had no part in the testing and did not know the respondents’ HIV status. Both those who had obtained their results and those who had not were approached for this follow-up interview. During this interview, respondents were asked about their sexual behavior in the prior two months and their attitudes toward condom use. At the end of the interview, respondents were given approximately 30 cents as appreciation for participation and were offered the opportunity to purchase condoms at half the subsidized retail price: five cents for a package of three condoms or two cents for a single condom. Respondents were allowed to purchase condoms only from the 30 cents they had just been given in order to prevent condom purchases from being correlated with any monetary incentive received two months prior at the results center. The maximum number of condoms that could be purchased was 18.

C. Sample Attrition and Test Refusals

The sample used for the main analysis in this paper consists of 2,812 residents of rural Malawi who accepted an HIV test, who had provided basic demographic data during the 2004 survey (age, village location), and whose HIV test result was not indeterminant (14 individuals). Although the original sample in 1998 was randomly drawn, sample attrition across waves of data collection affects the degree to which this sample is representative. The primary reason for attrition across all waves of data is temporary and permanent migration. For example, in 2004, 21 percent of those interviewed in 2001 were away or had moved, which is comparable to the attrition rates due to out-migration of other longitudinal studies in Africa (Antony Chapoto and Thomas S. Jayne 2005; John Maluccio 2000; Simona Bignami–Van Assche, Reniers, and Weinreb 2003). No village ever refused to participate in data collection and less than 1 percent of those approached in 2004 refused to be interviewed. Despite the attrition across waves of the MDICP panel, baseline characteristics in 2004 are similar to those of a population-based survey that was also conducted in Malawi in 2004 (NSO Malawi 2005). In that survey, 72.8 percent of the women (age 15–49) living in rural Malawi were married or cohabitating with a partner (versus 71 percent in the MDICP 2004 data); 4.3 percent of women and 13.1 percent of men reported using a condom at last intercourse (versus 16.4 percent of the women and 27.3 percent of the men who reported using a condom in the previous year in the MDICP 2004 data); and 14 percent reported ever having an HIV test (versus 18 percent in the MDICP 2004 data). These comparisons provide support to the external validity of the findings of this study for other rural populations in Malawi, and perhaps other rural parts of Africa.

Test refusals may also be a source of bias: 9 percent of those approached refused to be tested for HIV. In comparison to other studies conducting HIV testing, such as the DHS Malawi (2004), this is a relatively low refusal rate. This may be attributable to the method of testing through saliva, or to the fact that respondents were not required to learn their results at the time of testing. Observable characteristics (such as gender, age, or marital status) are not significant predictors of accepting an HIV test. Respondents’ prior beliefs of infection status also do not predict refusing an HIV test (Table 1, panel B). See also Francis Obare (2006). Among the main sample who agreed to be tested, 18 percent reported having been tested previously for HIV, although only half of these individuals reported actually receiving their results. Those who reported having a previous test were 6 percentage points more likely to agree to be tested by the MDICP nurses (Table 1, panel B). Not all spouses of respondents were offered a test: men who divorced or whose spouse died and spouses of the newly sampled adolescents were ineligible for testing.

While attrition from the panel across years suggests that the sample has disproportionately fewer mobile individuals—perhaps leading to a downward bias in the HIV prevalence rate and posing a potential threat to external validity—the sample who accepted an HIV test is relevant from a policy perspective in that it represents those who would be present during an HIV testing campaign in rural areas.

The follow-up interviews were conducted among 75 percent of those in the main sample in Balaka and Rumphi. Learning HIV results and HIV status itself are both separately associated with attrition from the follow-up survey. Being HIV-positive increases the likelihood of attrition by 17 percentage points, which could be due to death or sickness (Table 1, panel C). Having obtained HIV results from the VCT center decreases the likelihood of attrition by 24 percentage points, which to a certain extent is mechanical since those who were available to attend the VCT center were also more likely to be available for the follow-up interview (if, for example, they had not temporarily migrated). Importantly, all exogenously assigned variables (receiving an incentive, the amount of the incentive, and the distance from home to the VCT center) have no significant direct effect on likelihood of attrition at the follow-up. Thus, while sample attrition and HIV test refusals may pose a potential threat to the external validity of the study, the lack of differential attrition associated with incentives or distance minimizes risk to the internal validity of the study (Table 1, panel C).

II. Learning HIV Results

A. Theoretical Considerations

To the extent that individuals use the knowledge of their HIV test results to alter their behavior, there could be positive effects from HIV testing on sexual behavior. Those diagnosed negative can practice safe sex to protect themselves from future infection; those diagnosed positive can seek treatment, and if altruistic, can prevent spreading the virus to children or sexual partners. Furthermore, knowing HIV status may allow individuals to more realistically and effectively plan for the future. However, while people with treatable diseases have strong motivations for testing and diagnosis, these incentives may be absent for people concerned about HIV because it is incurable. Also, in low-income countries access to antiretroviral therapies that would slow disease progress is often limited, further reducing the incentive to learn HIV results (Peter Glick 2005; Jo Stein 2005). Moreover, even when antiretroviral therapies are available, most patients must wait until they have severe symptoms before receiving treatment. The costs of testing and travel may also prevent individuals from learning their HIV status (Steven Forsythe et al. 2002; Laver 2001; Areleen A. Leibowitz and Stephanie L. Taylor 2007; M. Isabel Fernandez et al. 2005) although testing rates are usually low even when testing services are free or low-cost. For example, although HIV testing is free in Malawi, only 14 percent of respondents reported ever having been tested (Malawi DHS 2004). Even when individuals choose to be tested for HIV, many do not return for their results: in meta-studies of clinics across Africa, only approximately 65 percent of individuals who tested for HIV returned to learn their results (Michel Cartoux et al. 1998; Donatus Ekwueme et al. 2003).7

It is therefore commonly suggested that psychological costs are important, perhaps crucial, barriers to testing and learning results. The psychological costs associated with learning HIV results can be either internal, such as having worry or fear, or external, such as experiencing social stigma (HITS 2004; F. Mugusi et al. 2002; S. Ginwalla et al. 2002; Rachel Baggaley et al. 1998; Angela B. Hutchinson et al. 2004; Kathleen Ford et al. 2004; Djeneba Coulibaly et al. 1998; Seth C. Kalichman and Leickness C. Simbayi 2003; and Brent Wolff et al. 2005).8

Monetary incentives may operate through several mechanisms to motivate individuals to learn their HIV status through testing. Incentives may directly compensate for the costs of learning HIV results, including the monetary costs of time or travel, or psychological costs. Monetary incentives may also reduce actual or anticipated social stigma. For example, while others could interpret attending a VCT center as a signal of self-perceived risk of infection or of prior unsafe sexual behavior, monetary incentives may provide individuals with an excuse for going to the center, thereby reducing negative inferences made by others.

B. Impact of Incentives and Distance on Learning HIV Results

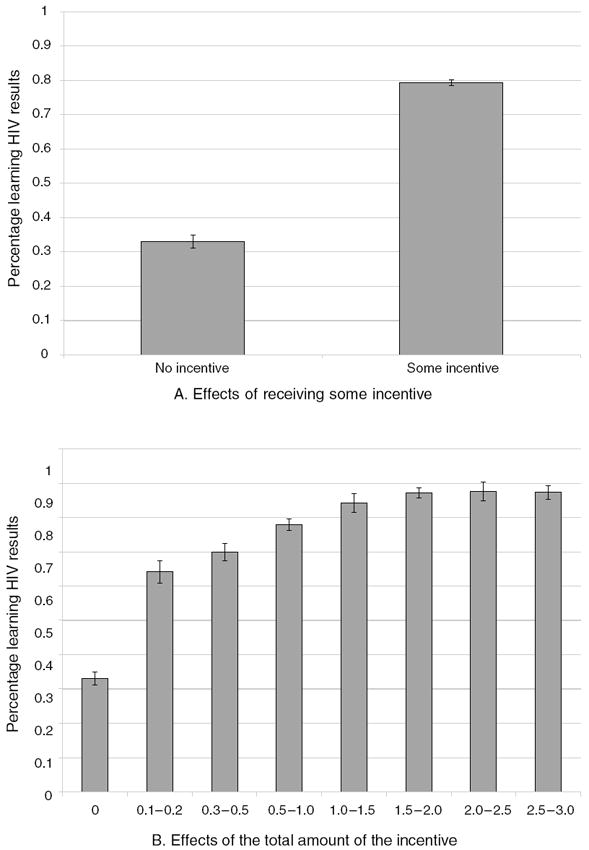

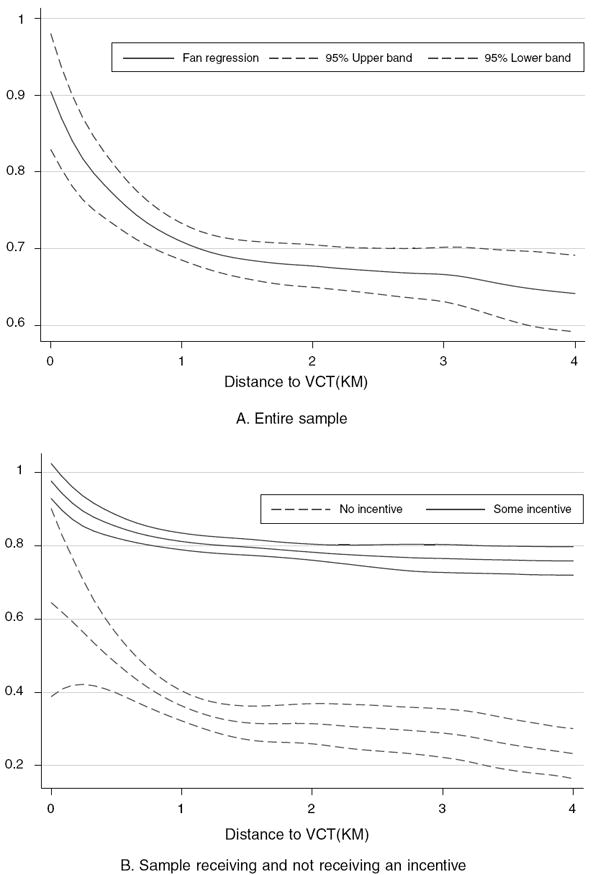

Across the three districts of the study area, 69 percent of all respondents attended a VCT center to obtain their HIV test results. Both incentives and distance to the center had large effects on seeking HIV results. Figure 3 presents the percent attending a results center as a function of receiving any incentive (panel A) and the total amount of the incentive (panel B). These figures illustrate the large impact of receiving an incentive on attendance. Error bars are also presented showing precisely estimated effects. Figure 4, panel A, presents the impact of distance of residence from the nearest results center on attendance, estimated by a nonparametric, locally weighted regression (Jianqing Fan 1992). Distance had a strong negative effect on attendance, especially pronounced among those living farther than 1.5 kilometers from the results center.

Figure 3. Percentage Returning for HIV Results.

Notes: Sample includes 2,812 individuals who tested for HIV; 0.05 percent error bars are presented. Figures present the percentage of individuals attending HIV results centers.

Figure 4. Impact of Distance to VCT on Returning for HIV Results.

Notes: Nonparametric Fan regression where distance is measured as a straight-line spherical distance from a respondent’s home to randomly assigned VCT center from geospatial coordinates and is measured in kilometers. Sample includes 2,812 individuals who tested for HIV. Lines indicate percentage attending the results centers and upper and lower confidence intervals.

To measure the demand for learning HIV results in a regression framework, I estimate:

| (1) |

Attendance at the VCT center is indicated by GotResults = 1 for person i in village j. Any indicates if the respondent received any nonzero voucher and Amt is the dollar amount of the incentive. Including the binary indicator as well as the squared term allows for nonlinear effects of the incentive. Dist is the number of kilometers from the randomly placed VCT center assigned to person i. A vector of controls, X, includes covariates of gender, age, age-squared, HIV status, and district dummies, as well as a control for a simulated average distance in each VCT zone. Because the locations of the centers were chosen randomly, as opposed to randomly assigning the distance needed to travel, I draw 1,000 simulated random locations in each VCT zone and calculate the average distance of each tested respondent from each of the 1,000 simulated locations. I average this distance for each respondent and take the mean across all respondents living in each zone.9 Standard errors are clustered by village, for 119 villages.10 Although the dependent variable is binary, the linear specifications do not differ greatly from estimations from probits; both results are presented (see also Joshua D. Angrist 2001).

Seeking HIV results was highly responsive to incentives. The average VCT center attendance of those receiving any positive-valued voucher is more than twice that of those receiving no incentive, a difference of 43 percentage points (Table 4, column 1). Moreover, the probability of center attendance increased by an additional 9.1 percentage points with every additional dollar of incentive (Table 4, column 2), with the nonlinear effect of the incentive also important (Table 4, column 3). Distance and distance-squared also had a significant impact on the likelihood of obtaining HIV results (Table 4, column 4). Those living more than 1.5 kilometers from the center were 3.8 percentage points, or 6 percent, less likely to seek their HIV results than those living within 1.5 kilometers (Table 4, column 5). The effect of offering ten cents (as compared to offering no incentive) was greater than the effect of distance. The effects of incentives and distance are similar when using a nonlinear model (Table 4, columns 6–10).

Table 4.

Impact of Monetary Incentives and Distance on Learning HIV Test Results (Dependent variable: Attendance at HIV results centers)

| OLS

|

Marginal probit

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

| Any incentive | 0.431*** (0.023) | 0.309*** (0.026) | 0.218*** (0.029) | 0.220*** (0.029) | 0.219*** (0.029) | 0.438*** (0.022) | 0.279*** (0.030) | 0.175*** (0.033) | 0.181*** (0.033) | 0.178*** (0.033) |

| Amount of incentive | 0.091*** (0.012) | 0.274*** (0.036) | 0.274*** (0.035) | 0.273*** (0.036) | 0.115*** (0.016) | 0.311*** (0.042) | 0.309*** (0.042) | 0.309*** (0.043) | ||

| Amount of incentive2 | −0.063*** (0.011) | −0.063*** (0.011) | −0.063*** (0.011) | −0.070*** (0.014) | −0.069*** (0.014) | −0.069*** (0.014) | ||||

| HIV | −0.055* (0.031) | −0.052 (0.032) | −0.05 (0.032) | −0.058* (0.031) | −0.055* (0.031) | −0.062* (0.036) | −0.063* (0.038) | −0.06 (0.037) | −0.069* (0.037) | −0.066* (0.037) |

| Distance (km) | −0.076*** (0.027) | −0.094*** (0.034) | ||||||||

| Distance2 | 0.010** (0.005) | 0.013** (0.006) | ||||||||

| Over 1.5 km | −0.037 (0.023) | −0.044* (0.026) | ||||||||

| Male | −0.01 (0.019) | −0.013 (0.018) | −0.015 (0.018) | −0.015 (0.018) | −0.014 (0.018) | −0.011 (0.021) | −0.016 (0.021) | −0.018 (0.021) | −0.018 (0.021) | −0.018 (0.021) |

| Age | 0.005 (0.003) | 0.004 (0.003) | 0.004 (0.003) | 0.004 (0.003) | 0.004 (0.003) | 0.005 (0.004) | 0.005 (0.004) | 0.004 (0.004) | 0.005 (0.003) | 0.005 (0.003) |

| Simulated average distance | 0.005 (0.014) | −0.007 (0.012) | 0.005 (0.016) | −0.008 (0.014) | ||||||

| Rumphi | −0.137*** (0.029) | −0.155*** (0.029) | −0.161*** (0.029) | −0.151*** (0.028) | −0.156*** (0.029) | −0.163*** (0.037) | −0.187*** (0.037) | −0.195*** (0.037) | −0.184*** (0.036) | −0.189*** (0.037) |

| Balaka | −0.118*** (0.023) | −0.123*** (0.024) | −0.122*** (0.024) | −0.114*** (0.026) | −0.109*** (0.027) | −0.144*** (0.031) | −0.149*** (0.032) | −0.148*** (0.033) | −0.139*** (0.036) | −0.132*** (0.036) |

| Constant | 0.346*** (0.059) | 0.365*** (0.058) | 0.370*** (0.058) | 0.442*** (0.067) | 0.395*** (0.060) | −0.144*** (0.031) | −0.149*** (0.032) | −0.140*** (0.034) | −0.133*** (0.035) | |

| Sample size | 2,812 | 2,812 | 2,812 | 2,812 | 2,812 | 2,812 | 2,812 | 2,812 | 2,812 | 2,812 |

| R2 | 0.18 | 0.2 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 |

| Average attendance | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.69 |

Notes: Sample includes individuals who tested for HIV and have demographic data. Columns 1–5 represent OLS coefficients and columns 6–10 represent marginal probit coefficients (dprobit); robust standard errors clustered by village (for 119 villages) with district fixed effects in parentheses. All specifications also include a term for age-squared. “Any incentive” is an indicator if the respondent received any nonzero monetary incentive. “HIV” is an indicator of being HIV positive. “Simulated average distance” is an average distance of respondents’ households to simulated randomized locations of HIV results centers. Distance is measured as a straight-line spherical distance from a respondent’s home to a randomly assigned VCT center from geospatial coordinates and is measured in kilometers.

Significantly different from zero at 99 percent confidence level.

Significantly different from zero at 95 percent confidence level.

Significantly different from zero at 90 percent confidence level.

VCT center attendance varied by HIV status. Overall, HIV-positive individuals were approximately 5.5 percentage points less likely to obtain their results (Table 4, column 1). In the district with the highest HIV prevalence rate, Balaka, those infected with HIV were 11 percentage points less likely to attend the center than those who were HIV-negative (standard error 0.043; Table 5, column 3). Overall, men were no more likely to attend than women. Age also had no impact on obtaining HIV results. Opportunity costs may also be important. For example, ever attending school reduced the probability of attending the VCT by 3.2 percentage points (standard error 0.019; regression not shown). VCT attendance varied by district and the coefficients on the district fixed-effects are significant (Table 4). Overall, 80 percent attended the result centers in Mchinji, 71 percent attended in Balaka, and 59 percent attended in Rumphi. These differences may be due, at least in part, to the timing of the test results availability, which coincided with planting season in Balaka and Rumphi and thus may have resulted in lower average attendance rates in these districts. Without more detailed time use data, however, the effects of the agricultural season cannot be distinguished from effects of characteristics that vary systematically by district.

Table 5.

Covariates and Interaction Effects with Incentives and Distance (Dependent variable: Attendance at HIV results centers)

| All respondents | Unmarried | Balaka | All respondents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Any incentive | 0.229*** (0.030) | 0.144*** (0.065) | 0.393*** (0.037) | 0.198*** (0.043) | 0.220*** (0.029) | 0.224*** (0.030) |

| Amount of incentive | 0.257*** (0.038) | 0.345*** (0.071) | 0.276*** (0.049) | 0.273*** (0.036) | 0.272*** (0.036) | 0.273*** (0.036) |

| Amount of incentive2 | −0.055*** (0.012) | −0.089*** (0.024) | −0.056*** (0.016) | −0.063*** (0.011) | −0.062*** (0.011) | −0.062*** (0.011) |

| Male | −0.004 (0.018) | 0.03 (0.036) | 0.114 (0.077) | −0.014 (0.018) | −0.015 (0.018) | −0.014 (0.018) |

| HIV | −0.045 (0.031) | 0.034 (0.078) | −0.114** (0.042) | −0.056* (0.031) | −0.023 (0.038) | −0.004 (0.074) |

| Over 1.5 km | −0.039* (0.023) | −0.007 (0.033) | −0.065 (0.041) | −0.064 (0.043) | −0.032 (0.024) | −0.036 (0.023) |

| Had previous HIV test | −0.019 (0.024) | |||||

| Treatment for HIV will be available | 0.005 (0.018) | |||||

| Married | 0.051*** (0.018) | |||||

| Never had sex | −0.037 (0.077) | |||||

| Never had sex × any | 0.107 (0.079) | |||||

| Any incentive × male | −0.161** (0.066) | |||||

| Over 1.5 km × any | 0.037 (0.044) | |||||

| HIV × any | −0.067 (0.062) | |||||

| Over 1.5 km × HIV | −0.066 (0.083) | |||||

| Constant | 0.452*** (0.037) | 0.482*** (0.065) | 0.224*** (0.055) | 0.412*** (0.065) | 0.393*** (0.061) | 0.392*** (0.060) |

| Sample size | 2,635 | 810 | 1,037 | 2,812 | 2,812 | 2,812 |

| R2 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 |

| Average attendance | 0.69 | 0.66 | 0.71 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.69 |

Notes: Sample includes individuals who tested for HIV and have age data. Columns represent OLS coefficients; robust standard errors clustered by village (for 119 villages) with district fixed effects in parentheses. “Any” is an indicator if the respondent received any nonzero monetary incentive and “amount” is the total value of the incentive. “HIV” is an indicator of being HIV positive. Also includes a simulated average distance (average distance of respondents’ households to simulated randomized locations of HIV results centers), age, and age-squared. Distance is measured as a straight-line spherical distance from a respondent’s home to randomly assigned VCT center from geospatial coordinates and is measured in kilometers.

Significantly different from zero at 99 percent confidence level.

Significantly different from zero at 95 percent confidence level.

Significantly different from zero at 90 percent confidence level.

Theoretically, those who are most uncertain of their HIV status would expect to gain the most from learning their results since those most certain of their status would expect to receive no new information. However, those who reported having had a previous test for HIV were no less likely to attend a VCT center than their untested counterparts—although among those who had been tested, only 54 percent reported knowing their HIV results. The likelihood of attendance was not significantly affected by having learned HIV test results prior to the 2004 MDICP survey (not shown).

The likelihood of seeking HIV results at a center was also not affected by respondents’ belief in the near-term availability of treatment for HIV, nor a belief of their own infection probability. Respondents were asked: “Do you think treatment for HIV (ARVs) will become available to most people in your area in the next five years?” In all, 34 percent reported believing treatment would be available for HIV-positive persons (Table 2, panel B) but rate of attendance did not vary among those who believed treatment would be available and those who did not (Table 5, column 1). Individuals were also asked: “What is the chance that you are infected with HIV?” Possible answers were “no likelihood,” “some likelihood,” “high likelihood,” and “don’t know.” There were no significant differences in attendance between individuals having varying subjective probabilities of infection (not shown). One reason why attendance did not vary with prior beliefs may be that respondents’ priors may be unreliable. There is evidence that respondents had a tendency to overestimate their own likelihood of HIV infection (Philip Anglewicz and Hans-Peter Kohler 2006; Bignami–Van Assche et al. 2005; see also Table 10 and discussion below).

Table 10.

Average Belief of Likelihood of Infection before and after VCT (Dependent variable: Likely to be HIV infected)

| Panel A: HIV negative | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline survey | Follow-up survey

|

||||||

| (1) | Did not get results (2) | Got results (3) | Difference (4) | ||||

| 0.43 | (0.49) | 0.49 | (0.50) | 0.13 | (0.33) | −0.38*** | (0.03) |

|

| |||||||

| Panel B: HIV positive | |||||||

| Baseline survey | Follow-up survey

|

||||||

| (1) | Did not get results (2) | Got results (3) | Difference (4) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| 0.58 | (0.50) | 0.46 | (0.51) | 0.5 | (0.51) | 0.03 | (0.12) |

Notes: Sample includes respondents in Balaka and Rumphi who were tested for HIV and were reinterviewed in 2005. Robust standard errors clustered by village with district fixed effects are in parentheses. Controls also include gender, age, and age squared. “Likely to be infected” is equal to zero if the respondent reported no likelihood of HIV infection, and one otherwise. Sample includes 2,428 HIV-negatives and 165 HIV-positives in the baseline survey and 1,430 HIV-negatives and 72 HIV-positives in the follow-up survey.

Significantly different from zero at 99 percent confidence level.

Significantly different from zero at 95 percent confidence level.

Significantly different from zero at 90 percent confidence level.

Those who had never had sex would have little reason to attend the VCT center, except to redeem a monetary voucher. Although not statistically significant, the impact of receiving an incentive is much more elastic among unmarried respondents who report never having had sex, who were 11 percentage points more likely to attend a center (and redeem their voucher) than those who ever had sex, and who also received an incentive (Table 5, column 2). Alternatively, those who were married in 2004 were 5.1 percentage points more likely to return for their results than those who were not married (Table 5, column 1).

Receiving a voucher may have provided justification for some individuals to attend the center. For example, because of historical gender restrictions within Islam, women in Balaka may have more travel restrictions, preventing them from easily attending the results centers.11 In Balaka, men receiving no incentive were significantly more likely to attend the center than women receiving no incentive. However, men and women receiving an incentive are equally likely to attend, closing the gender gap of attendance in Balaka (Table 5, column 3). In Mchinji and Rumphi there were no differential impacts of the incentive on attendance between men and women.

Monetary incentives were also especially important for those living farther from the VCT center: for those living over 1.5 kilometers from the HIV results center, there was an additional impact of receiving an incentive, increasing attendance by 3.7 percentage points, although the difference is not statistically significant (Table 5, column 4). This effect can also be seen in Figure 4, panel B, which graphs the impact of distance on attendance among those receiving any incentive and those receiving no incentive. Despite the interaction between distance and incentives, evidence suggests an upper bound to the distance that individuals are willing to travel to learn their results, regardless of the incentives offered. Several VCT centers that were initially placed more than nine kilometers from sample households had no attendance for several days. These centers were re-sited at new random locations and respondents were informed of the new locations. These distant locations are excluded from the analysis. This suggests that in the absence of monetary incentives, distance and transaction costs may be the strongest contributing factors to low rates of obtaining results. On the other hand, it may be that increased distance also increased the likelihood that respondents did not know the location of the VCT sites, confounding the interpretation that travel costs alone reduce attendance.

HIV-positive individuals receiving an incentive were less likely to seek their test results than those who were HIV-negative (Table 5, column 5). There was also an effect of being HIV positive and living farther away from the VCT center: HIV-positives living over 1.5 kilometers from the center were approximately 6.6 percentage points less likely to attend than HIV-negatives living over 1.5 kilometers, perhaps because they were more likely to be sick, making travel more costly (Table 5, column 6). However, these differences were not statistically significant, likely due in part to the small number of HIV-positive individuals.

In sum, both monetary incentives and distance had large impacts on obtaining HIV results. Many have suggested that psychological barriers, such as fear or stigma, play an important role in deterring individuals from testing (or seeking test results). I find, however, that these barriers, if they exist at all, can be easily overcome by offering small cash rewards. Incentives may compensate individuals directly for their cost of obtaining results or serve as a public justification for attending a results center, indirectly reducing psychological costs. One woman’s remark, overheard by an interviewer, is especially illustrative:

Those who were lucky were picking [vouchers] with some figures and those were courageous to go and check their blood test results because they were also receiving their money there so like me where I got a zero. I did not even go and check the results because I knew that there was nothing for me there (Malawi Diffusion Ideational Change Project 2004).

These findings reemphasize the importance of economic costs such as travel or opportunity costs in decision making and the effects of monetary incentives to overcome these costs.

III. Impact of Learning HIV Status

A. Theoretical and Measurement Considerations

In a standard expected utility framework, individuals do not receive any additional utility from learning their HIV status. Testing is beneficial only to the extent that it provides new information that can be used for updating behavior.12 However, it is theoretically ambiguous how the knowledge of HIV status affects sexual behavior and, in particular, the demand for condoms. For those diagnosed HIV-positive, the direct benefits of using condoms fall because (if safe sex is costly) there is no longer any need of protection. However, HIV-positive individuals who are sufficiently altruistic may exhibit a higher demand for condoms after learning their status. On the other hand, if infected individuals behave selfishly, there may be a decrease in the demand for condoms (Stephane Mechoulan 2004). For HIV-negatives, it is similarly ambiguous: the benefit from using condoms—i.e., to remain uninfected—may increase after diagnosis; however, the lack of need to protect a sexual partner may cause condom use to fall.13 Thus, how learning HIV results affects sexual behavior is ultimately an empirical question.

Previous studies examining the effects of HIV testing on sexual behavior have not only been inconclusive, but also suffer from selection bias in terms of which individuals chose to learn their results.14 In this study, however, the randomly assigned VCT center distances and monetary incentives serve as exogenous instruments for knowledge of status. Nevertheless, several estimation challenges and limitations remain.

One challenge to measuring the demand for safe sex in response to HIV testing is that sexual behavior is difficult to measure and self-reports may be unreliable. Prior research has found that sexual behavior, such as number of sexual partners, is likely to be underreported and that contraceptive use is sometimes overreported (Landon Myer, C. Morroni, and B. G. Link 2004; Susan Allen et al. 2003). Because of the potential bias of self-reports, the primary outcome variable used to measure the demand for safe sex in this paper is the actual purchase of condoms from survey interviewers. To mitigate potential reporting biases during follow-up interviews, every effort was made to conduct interviews privately with an interviewer of the same sex as the respondent, who had no part in the HIV testing or in giving results.

It is important to keep in mind that condom purchases may not reflect the true demand for safe sex. If knowledge of HIV status increases abstinence, the demand for condoms could fall in response to obtaining test results. Also, the impact of learning HIV status on condom purchases is likely to differ between those with a sexual partner and those without. And because partnership may be endogenous to learning HIV results (Georges Reniers 2005), I differentiate between those who were and who were not sexually active at the time of the baseline survey (before testing). It is worth noting, however, that there were no significant changes in marriage or partnership attributable to learning HIV status between the time of the HIV results being available and the follow-up survey (not shown).

B. Summary Statistics of Sexual Activity and Condom Use

In the baseline 2004 survey, 76 percent of the follow-up sample reported having had sex during the previous year (Table 2, panel B). In the follow-up 2005 survey, 62 percent of the sample reported having had sex during the previous two months (Table 2, panel D). Of those who reported having sex, only 3.3 percent reported having sex with more than one partner, although the majority of these individuals were polygamous men. At the time of the follow-up survey, respondents were also asked if they had purchased condoms at any time between the opportunity to obtain test results and the follow-up interviews: only 8 percent of the sample reported purchasing condoms during those two months. In terms of the subsidized condoms that were offered at the end of the follow-up interview, 24 percent purchased at least one condom; of those who purchased any condoms, the average number purchased was 3.7 (Table 2, panel D). This rate of condom purchases is similar to the condom use reported in the 2004 main survey, where 21 percent of all respondents reported using a condom with a sexual partner during the prior year (Table 2, panel B). Only three individuals purchased the maximum possible number of condoms. Men were more likely to purchase than women: 31 percent of men purchased condoms while 18 percent of women purchased at least one condom. However, conditional on purchasing any condoms, men and women purchase the same number, on average (not shown). Among HIV-positives, men and women were equally likely to purchase condoms at the follow-up survey. Among all respondents, married and unmarried respondents were equally likely to purchase condoms. However, purchase of condoms did vary by reported sexual activity: condoms were purchased by 26 percent of respondents who in 2004 reported having had sex in the prior year as opposed to 21 percent of those who reported not having had sex.

C. Receiving HIV-Positive and Negative Diagnoses

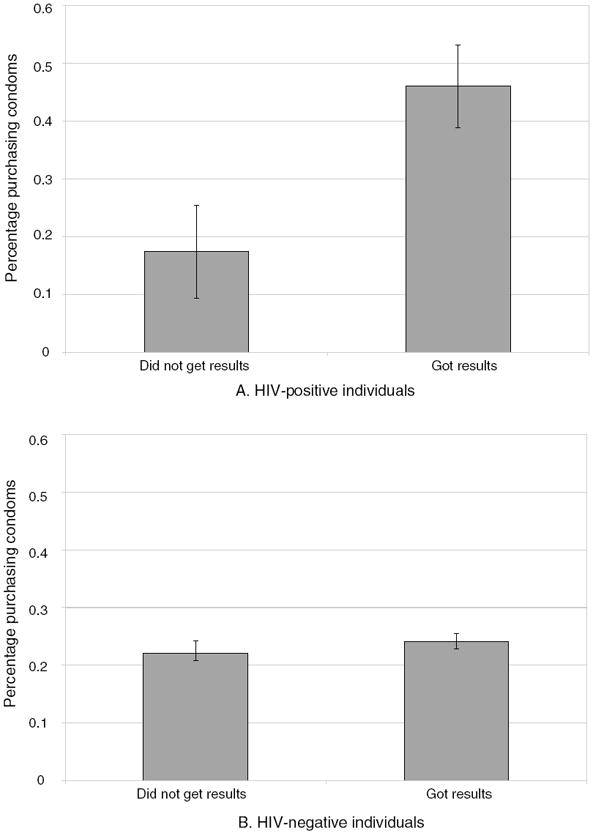

Panel A of Figure 5 presents the percent purchasing condoms among those who knew and did not know their HIV status. For HIV-positive respondents, those who obtained their test results were more than twice as likely to purchase condoms as those who did not, while among HIV-negative individuals, condom purchase did not vary significantly by knowledge of HIV status (Figure 5, panel B).

Figure 5. Percentage Purchasing Condoms.

Notes: Sample includes 1,524 respondents in Balaka and Rumphi who were tested for HIV and reinterviewed in 2005 who reported having sex during 2004 (at the baseline). Figures present the percent purchasing condoms at a follow-up interview two months after testing.

I measure the effects of learning HIV results with the following regression:

| (2) |

Y indicates condom purchase at the time of the follow-up survey (as measured by whether the respondent purchased condoms or the total number of condoms purchased) or if the respondent reported having sex; and GotResults indicates knowledge of HIV status. The fact that individuals choose to learn their HIV status means that OLS estimates are likely to be biased, but estimating the effects of knowing HIV status with exogenous instruments provides unbiased estimates. In particular, I instrument GotResults with being offered any incentive, the amount of the incentive, the amount of the incentive squared, the distance from the HIV result center, and distance-squared. Table 6 presents first-stage OLS regressions; the F-statistics for this specification and sample of sexually active respondents are equal to 74.98 and 193.29, respectively. To account for differential effects among men and women, I also include interactions with gender:

| (3) |

Table 6.

First Stage

| Got results (1) | HIV × got results (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Any incentive | 0.153* (0.081) | −0.001 (0.004) |

| Amount of incentive | 0.309*** (0.089) | 0.001 (0.002) |

| Amount of incentive2 | −0.067** (0.026) | 0.000 (0.001) |

| Distance (km) | −0.117* (0.062) | 0.003 (0.005) |

| Distance2 | 0.018 (0.011) | 0.000 (0.001) |

| Any × male | 0.047 (0.104) | −0.001 (0.006) |

| Amount × male | −0.058 (0.130) | −0.001 (0.002) |

| Amount2 × male | 0.023 (0.040) | 0.000 (0.001) |

| Distance × male | 0.199** (0.076) | −0.003 (0.011) |

| Distance2 × male | −0.033** (0.013) | 0.001 (0.002) |

| Any × male × HIV | −0.161 (0.442) | −0.185 (0.392) |

| Amount × male × HIV | −0.714 (0.638) | −0.778 (0.592) |

| Amount2 × male × HIV | 0.195 (0.177) | 0.23 (0.172) |

| Distance × male × HIV | 0.401** (0.193) | 0.385** (0.184) |

| Distance2 × male × HIV | −0.059 (0.036) | −0.054 (0.036) |

| Any × HIV | −0.067 (0.235) | 0.165 (0.213) |

| Amount × HIV | 0.750* (0.377) | 1.035*** (0.350) |

| Amount2 × HIV | −0.235** (0.115) | −0.301*** (0.109) |

| Distance × HIV | −0.171 (0.237) | −0.221 (0.224) |

| Distance2 × HIV | 0.034 (0.046) | 0.04 (0.045) |

| HIV | −0.231 (0.275) | 0.236 (0.259) |

| Male | −0.279** (0.112) | 0.004 (0.018) |

| Constant | 0.406*** (0.103) | 0.026* (0.015) |

| Observations | 1,008 | 1,008 |

| R2 | 0.22 | 0.76 |

| F–statistic | 74.98 | 193.29 |

Notes: Sample includes individuals who tested for HIV, have age data, and who had sex in 2004. Columns represent OLS coefficients; robust standard errors clustered by village (for 57 villages) with district fixed effects. “Any incentive” is an indicator if the respondent received any nonzero incentive. “HIV” indicates being HIV positive. Distance is measured as a straight-line spherical distance from a respondent’s home to randomly assigned VCT center from geospatial coordinates and is measured in kilometers. Also includes controls for age, age-squared, simulated average distance, and a district fixed effect.

Significantly different from zero at 99 percent confidence level.

Significantly different from zero at 95 percent confidence level.

Significantly different from zero at 90 percent confidence level.

In equation (2), GotResults×HIV represents the differential effect of receiving an HIV-positive diagnosis, and this is instrumented with the same set of instruments as in (3) above, interacted by HIV status. Because the monetary incentives and distances to VCT centers were both exogenously assigned to each individual, they are uncorrelated with the error term. In the analysis, although the measure of purchasing condoms is binary, estimates do not differ greatly from a nonlinear specification. Both specifications are presented.

Covariates, X, include age, age-squared, a dummy for male, simulated average distance to the VCT center, and district dummies. It is also important to point out that the IV estimates in (2) are local average treatment effects (LATE), which represent a weighted average per-unit treatment effect, where the weight is proportional to the number of people affected by the instruments, not necessarily equal to the average treatment effect (Guido W. Imbens and Angrist 1994; Angrist and Imbens 1995; Angrist et al. 1996). Also, while I account for some heterogeneous treatment effects by including interactions with gender, there may be other differential effects of the incentive and distance that are not included in the IV analysis (see Imbens and Angrist 1994; Heckman and Jeffrey Smith 1997; Heckman 2001; Heckman et al. 2006).15

I first examine the effects of receiving an HIV diagnosis on condom purchases and reported sexual activity among those who reported having sex at the time of the baseline survey: 63 percent of HIV-negative and 66 percent of HIV-positive individuals.16 Note that this reduces the sample of HIV-positives for the analysis and thus much of the focus of the analysis is among the HIV-negatives or pooled regressions. Row 1 of Table 7 shows no significant effects of learning HIV-negative results on any measure of condom purchase or recent sexual activity among those who had sex at baseline (Table 7, columns 2, 4, 6, and 8). However, the standard errors of the IV estimates are large, making it impossible to reject “no impact of learning HIV-negative status.”

Table 7.

Reactions to Learning HIV Results among Sexually Active at Baseline

| Dependent variables: | Bought condoms | Number of condoms bought | Reported buying condoms | Reported having sex at follow-up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLS (1) | IV (2) | OLS (3) | IV (4) | OLS (5) | IV (6) | OLS (7) | IV (8) | |

| Got results | −0.022 (0.025) | −0.069 (0.062) | −0.193 (0.148) | −0.303 (0.285) | −0.006 (0.018) | 0.017 (0.050) | 0.016 (0.032) | −0.004 (0.060) |

| Got results × HIV | 0.418*** (0.143) | 0.248 (0.169) | 1.778*** (0.564) | 1.689** (0.784) | 0.098 (0.084) | −0.027 (0.092) | −0.072 (0.121) | −0.079 (0.229) |

| HIV | −0.175** (0.085) | −0.073 (0.123) | −0.873*** (0.275) | −0.831 (0.375) | −0.029 (0.055) | 0.053 (0.074) | −0.043 (0.112) | −0.041 (0.156) |

| Male | 0.114*** (0.026) | 0.111*** (0.026) | 0.413*** (0.116) | 0.408*** (0.116) | 0.116*** (0.021) | 0.117*** (0.021) | −0.02 (0.028) | −0.021 (0.028) |

| Age | −0.007 (0.005) | −0.007 (0.005) | −0.03 (0.029) | −0.029 (0.028) | −0.004 (0.003) | −0.005 (0.003) | 0.027*** (0.005) | 0.027*** (0.005) |

| Age2 | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | −0.000*** (0.000) | −0.000*** (0.000) |

| Simulated average distance | −0.048** (0.022) | −0.048** (0.021) | −0.153** (0.065) | −0.154** (0.065) | −0.008 (0.012) | −0.008 (0.012) | 0.028** (0.013) | 0.028** (0.013) |

| Rumphi | −0.349*** (0.037) | −0.355*** (0.039) | −1.065*** (0.129) | −1.078*** (0.123) | −0.046** (0.023) | −0.044** (0.021) | −0.068** (0.029) | −0.070** (0.029) |

| Constant | 0.728*** (0.109) | 0.764*** (0.118) | 2.688*** (0.474) | 2.761*** (0.539) | 0.216*** (0.069) | 0.206** (0.076) | 0.207** (0.098) | 0.220** (0.101) |

| Sample Size | 1,008 | 1,008 | 1,008 | 1,008 | 1,008 | 1,008 | 1,008 | 1,008 |

| R2 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| Mean | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.73 | 0.73 |

| p-Statistic (got results + got results × HIV = 0) | 0.01 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.26 | 0.90 | 0.64 | 0.69 |

Notes: Sample includes HIV-positive and negative respondents in Balaka and Rumphi who were tested for HIV, were reinterviewed in 2005, and who had sex in 2004. Robust standard errors clustered by village (for 57 villages) with district fixed effects are in parentheses. Simulated average distance variable (an average distance of respondents’ households to simulated randomized locations of HIV results centers). Coefficients are either OLS or IV estimates where knowing HIV status is instrumented by having any positive-valued incentive, the total amount of the incentive, total amount squared, distance from the HIV results center, distance-squared, and all terms interacted with gender and HIV status. “Bought condoms” is an indicator if any condoms were purchased from interviewers at the follow-up survey; “number of condoms” is the total number of condoms purchased from interviewers; “reported buying condoms” and “reported having sex” were asked at the follow-up interview in 2005 and refer to the previous two months since the VCT was available.

Significantly different from zero at 99 percent confidence level.

Significantly different from zero at 95 percent confidence level.

Significantly different from zero at 90 percent confidence level.

Overall, while HIV-positive individuals were significantly less likely to purchase condoms from the survey interviewers or report purchasing condoms on their own, receiving an HIV-positive diagnosis resulted in an increase in condom purchases. Among those with a sexual partner at the time of the 2004 baseline survey, those obtaining HIV-positive results were 25 percentage points more likely to purchase condoms than HIV-positive persons who did not learn their results (although statistically insignificant in the IV specification of Table 7, column 2). This result is statistically significant when measuring the total number of condoms purchased as an outcome, where the average number of condoms purchased increased by 1.69 condoms after receiving an HIV-positive diagnosis (Table 7, column 4). The p-value of the total impact of receiving an HIV-positive diagnosis is 0.07, presented in Table 7.

Recall that the condoms sold during the follow-up study were subsidized in price and were offered for purchase at the respondent’s home–significantly lowering the cost of travel to obtain condoms at local stores. In regards to the nonsubsidized condoms, respondents were asked if they had purchased any condoms during the two months after that test results were available at the VCT centers. There is a positive, although statistically insignificant, relationship between receiving an HIV-positive test result and the reported purchase of nonsubsidized condoms during the two months after HIV test results were available in the OLS, but not in the IV (Table 7, columns 5 and 6). There is also a negative (also statistically insignificant) relationship between receiving HIV-positive results on the probability of having sex at follow-up (Table 7, column 8).

Theoretically, if individuals who were more likely to practice safe sex were also more likely to choose to learn their HIV status and also purchase more condoms at the follow-up, not accounting for selection bias would overestimate the true impact of learning HIV results on later sexual behavior. However, comparing the OLS estimates to the IV estimates of the impact of learning HIV results on condom purchases (Table 7) indicates no consistent pattern across each column, and the differences between the OLS and IV estimates are neither large nor statistically significant for either HIV-negative or HIV-positive individuals (not shown).

Several of the outcome variables in Table 7 are binary, possibly warranting a nonlinear estimation strategy. However, estimation of binary regression models with binary endogenous variables is difficult and there are often problems with convergence or concavity of the log likelihood surface (David A. Freedman and Jasjeet S. Sekhon 2008; see also Edward Vytlacil and Nese Yildiz 2007; Jacob Nielsen Arendt and Anders Holm 2006). One strategy suggested by Heckman (1978) is to estimate a bivariate probit model. In order to estimate the effects of learning HIV results on the likelihood of purchasing any condoms using this nonlinear strategy, it is necessary to divide the sample by HIV status and estimate the effect of obtaining HIV test results on positive and negative individuals separately. Because the sample is not pooled among HIV-positives and HIV-negatives, the nonlinear estimates presented in Table 8 are not directly comparable to those in Table 7. I therefore present linear OLS and IV estimates as well as the marginal probit and marginal biprobit (accounting for endogeneity) estimates on the impact of learning HIV results on condom purchases among HIV-positives and negatives.17

Table 8.

Probit Estimates: Reactions to Learning HIV Results

| Dependent variable: Bought any condoms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLS (1) | IV (2) | Probit (marginal effects) (3) | Bivariate probit (marginal effects) (4) | |

| Panel A: HIV positive | ||||

| Got results | 0.427*** (0.149) | 0.273 (0.200) | 0.437*** (0.138) | 0.370*** (0.141) |

| Male | 0.038 (0.115) | 0.024 (0.117) | 0.043 (0.129) | 0.026 (0.131) |

| Age | 0.001 (0.040) | −0.018 (0.043) | 0.004 (0.039) | −0.009 (0.038) |

| Age2 | 0.000 (0.001) | 0.000 (0.001) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) |

| Simulated average distance | 0.025 (0.074) | 0.026 (0.072) | 0.026 (0.074) | 0.025 (0.074) |

| Rumphi | −0.084 (0.179) | −0.08 (0.177) | −0.126 (0.195) | −0.117 (0.193) |

| Constant | 0.055 (0.823) | 0.511 (0.974) | ||

| Sample size | 52 | 52 | 52 | 52 |

| R2 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.18 | |

| Mean | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.38 |

|

| ||||

| Panel B: HIV negative | ||||

| Got results | −0.023 (0.025) | −0.072 (0.061) | −0.033 (0.029) | −0.128 (0.088) |

| Male | 0.113*** (0.028) | 0.111*** (0.027) | 0.118*** (0.029) | 0.114*** (0.029) |

| Age | −0.007 (0.005) | −0.006 (0.005) | −0.005 (0.005) | −0.004 (0.005) |

| Age2 | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) |

| Simulated average distance | −0.052** (0.022) | −0.053** (0.022) | −0.043** (0.018) | −0.044** (0.018) |

| Rumphi | −0.362*** (0.040) | −0.368*** (0.041) | −0.356*** (0.036) | −0.365*** (0.037) |

| Constant | 0.754*** (0.109) | 0.784*** (0.116) | ||

| Sample size | 956 | 956 | 956 | 956 |

| R2 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.18 | |

| Mean | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

Notes: Sample includes HIV-positive and negative respondents in Balaka and Rumphi who were tested for HIV, were reinterviewed in 2005, and who had sex in 2004. Robust standard errors clustered by village (for 57 villages) with district fixed effects are in parentheses. Coefficients in column 1 are linear OLS estimates. Coefficients in column 2 are linear IV estimates where knowing HIV status is instrumented by having any nonzero incentive, the total amount of the incentive, total amount squared, distance from the HIV results center, distance-squared, and all terms interacted with gender. Column 3 presents marginal probit estimates, which do not control for endogenous selection into learning HIV results. Column 4 presents the marginal effects of a seemingly unrelated bivariate probit, controlling for endogenous selection into learning HIV results (see text).

Significantly different from zero at 99 percent confidence level.

Significantly different from zero at 95 percent confidence level.

Significantly different from zero at 90 percent confidence level.

The linear results in column 2, Table 8, do not differ substantively from the nonlinear biprobit specification in column 4, Table 8; however, the magnitudes of the coefficients and statistical significance do vary slightly. In particular, while the coefficient on GotResults does not differ greatly among the HIV-negatives (Table 8, panel B), among HIV-positives the coefficient in the nonlinear case is statistically significant at the 99 percent level (Table 8, panel A). The coefficient is also greater in the bivariate probit specification than in the linear model, suggesting an even larger effect of learning HIV-positive results on the likelihood of purchasing condoms. On the other hand, the difference between the two specifications may be due in part to the small sample size of HIV-positives. Given the difficulties with this estimation, including in particular the fact that it is necessary to separate the samples when doing the biprobit estimation, the linear IV specification in Table 7 remains the preferred estimation model.18

The results in Table 7 and Table 8 together suggest that overall, while there was no impact of receiving an HIV-negative diagnosis, receiving an HIV-positive diagnosis had positive effects on subsequent condom purchases. In the linear specification, the estimated impact of learning HIV-positive results on the likelihood of purchasing any condoms is large, although statistically insignificant at traditional confidence levels (Table 7, column 2). However, there is a statistically significant effect of learning HIV-positive results on the total number of condoms purchased (Table 7, column 4). In the nonlinear case, the coefficient on GotResults is statistically significant and large (Table 8, column 4): an HIV-positive individual who learned his HIV status was 37 percentage points more likely to purchase condoms than an HIV-positive individual who did not learn his results.

D. Other Considerations

It is possible that respondents who knew themselves to be HIV-positive were motivated to purchase condoms solely out of guilt, believing (incorrectly) that the interviewer knew their status. If this were the case, they may have purchased only one condom as a token, keeping the remaining money. However, only two of all the HIV-positives purchased a single condom; and omitting these individuals or coding their purchases as zero does not affect any of the results. Although impossible to rule out, this suggests that guilt or shame may not have been a large factor in the observed increase in condom sales among HIV-positives learning their results. Moreover, if HIV-positives purchased condoms solely out of guilt or social pressure, this would mean that the results of these analyses are upper bounds of the true impact of learning HIV status. Another consideration is that the outcome variable is condoms purchased rather than condoms used during sexual activity—which would also contribute to the results being an upward bias of the actual effect of learning HIV-positive results.19 It is also possible that respondents purchased condoms with the intention of reselling the condoms, rather than using them. To the extent that resale is uncorrelated with the randomly assigned incentives and distance, this would not threaten the internal validity of results.

There were no differential effects of learning HIV-negative status on condom purchases between those who were and were not sexually active at the baseline (Table 9). There were also no differential effects of learning HIV status (either positive or negative) on condom purchases among other observable respondent characteristics. For example, although men on average were more likely to purchase condoms than women, there were no differences in the impact of learning HIV status on purchases by gender. There were also no differences by age, or ever having attended school (not shown). Learning HIV-positive or negative results did not significantly affect having discussions with friends or spouses about condoms or AIDS. Respondents were also asked about their attitudes about condoms. These attitudes were strong determinants of purchasing condoms; for example, those who “agreed” that condoms were acceptable to use with a spouse were twice as likely to purchase condoms as those who “disagreed.” However, there were no effects of receiving either a positive or negative diagnosis on attitudes about condoms among either HIV-positive or negative individuals (not shown).

Table 9.

Learning HIV-Negative Results—Interactions with Prior Sexual Behavior

| Dependent variables: | Bought condoms

|

Number of condoms

|

Reported buying condoms

|

Reported having sex at follow-up

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OLS (1) | IV (2) | OLS (3) | IV (4) | OLS (5) | IV (6) | OLS (7) | IV (8) | |

| Got results | 0.024 (0.047) | 0.007 (0.100) | 0.03 (0.189) | −0.141 (0.453) | −0.029 (0.028) | −0.041 (0.058) | 0.027 (0.062) | −0.073 (0.140) |

| Got results × had sex | −0.043 (0.054) | −0.061 (0.127) | −0.207 (0.250) | −0.13 (0.577) | 0.023 (0.033) | 0.058 (0.074) | −0.013 (0.066) | 0.068 (0.148) |

| Had sex | 0.068 (0.047) | 0.081 (0.086) | 0.355 (0.213) | 0.301 (0.409) | −0.001 (0.030) | −0.026 (0.052) | 0.247*** (0.063) | 0.189* (0.112) |

| Constant | 0.595*** (0.111) | 0.605*** (0.112) | 2.081*** (0.481) | 2.196*** (0.502) | 0.194*** (0.062) | 0.204** (0.077) | −0.206** (0.088) | −0.137 (0.129) |

| Sample size | 1,260 | 1,260 | 1,260 | 1,260 | 1,260 | 1,260 | 1,260 | 1,260 |

| R2 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Mean | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.67 | 0.67 |

| P-statistic (got results + got results × had sex = 0) | 0.46 | 0.40 | 0.24 | 0.36 | 0.76 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.93 |