Abstract

Objective

To determine whether serum levels of N-terminal (NT) pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (pro-BNP) are higher in patients with poorly compressible arteries (PCA) than in patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) and control subjects without PCA or PAD.

Methods and Results

Medial arterial calcification in the lower extremities results in PCA and may be associated with increased arterial stiffness and hemodynamic/myocardial stress. PCA was defined as having an ankle-brachial index >1.4 or an ankle blood pressure >255 mm Hg, whereas PAD was defined as having an ankle-brachial index ≤0.9. Study participants with PCA (n=100; aged 71±10 years; 70% men) and age- and sex-matched patients with PAD (n=300) were recruited from the noninvasive vascular laboratory. Age- and sex-matched controls (n=300) were identified from a community-based cohort and had no history of PAD. NT pro-BNP levels were approximately 2.5-fold higher in patients with PCA than in patients with PAD and approximately 4-fold higher than in age- and sex-matched controls. In multivariable regression analyses that adjusted for age, sex, smoking, hypertension, history of coronary heart disease/stroke, systolic blood pressure, and serum creatinine, NT pro-BNP levels remained significantly higher in patients with PCA than in patients with PAD and controls (P<0.001).

Conclusion

Patients with medial arterial calcification and PCA have higher serum levels of NT pro-BNP than patients with PAD and controls, which is suggestive of an adverse hemodynamic milieu and increased risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

Keywords: medial arterial calcification, poorly compressible arteries, peripheral artery disease, NT pro-BNP, arterial stiffness, natriuretic peptides, risk factors

Medial arterial calcification, first described by Monckeberg in 1902,1 was initially thought to be a benign condition associated with aging. Subsequently, arterial calcification on radiographs of the feet was associated with increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, especially in patients with diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease.2,3 Medial arterial calcification typically affects the lower extremity arterial bed and results in poorly compressible arteries (PCA) and an artifactually high ankle blood pressure (BP) and ankle-brachial index (ABI). In the clinical setting, patients referred for noninvasive arterial evaluation are considered to have PCA if they have an ABI >1.4 or if the ankle BP is >255 mm Hg. In the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (1999 to 2000 and 2001 to 2002), 1.4% of adults >40 years had an ABI >1.4, suggesting that at least 1.6 million individuals in the United States have medial arterial calcification.4 Patients with an ABI >1.4 have similar or even greater cardiovascular and all-cause mortality when compared with patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) (ABI ≤0.9).5 Moreover, patients with PCA often have significant additional comorbidities, such as diabetes and chronic kidney disease, that add to the risk of adverse outcomes.6,7

A possible consequence of medial arterial calcification is increased arterial stiffness and, thereby, increased hemodynamic stress.8,9 Circulating levels of N-terminal (NT) pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (pro-BNP), a marker of hemodynamic stress, are elevated in patients with increased left ventricular mass, coronary heart disease (CHD), and PAD.10–12 Higher levels are also associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in asymptomatic individuals and in patients with CHD and PAD.13–15 We hypothesized that patients with PCA have increased hemodynamic and myocardial stress that may lead to elevated NT pro-BNP levels. To test our hypothesis, we measured NT pro-BNP levels in patients with PCA and compared these with levels in age- and sex-matched patients with PAD and in age- and sex-matched control subjects without a history of PAD.

Methods

Patients with PCA and PAD were identified from the noninvasive vascular laboratory at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn, between December 1, 2006 and December 1, 2008. A total of 107 patients with PCA and 513 patients with PAD were recruited during this period. The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic institutional review board, and informed consent was obtained from participants.

Noninvasive Arterial Evaluation

Patients suspected of having PAD are evaluated by measuring ABI at rest and 1 min postexercise and obtaining continuous-wave Doppler and pulse-volume recordings. The ABI is the ratio of BP at the ankle to BP at the arm. Normally >1.0, the ratio decreases in the setting of atherosclerosis of the leg arteries, leading to arterial narrowing. The ABI is measured in the supine position according to a standardized protocol. Appropriately sized BP cuffs are placed over each brachial artery and above each malleolus, and systolic BP is measured using a handheld 8.3-MHz Doppler probe. The higher of the 2 systolic brachial BP measurements is used to calculate the ABI. A standard treadmill test with a speed of 1 to 2 mile/h and a fixed grade of 10° with continuous electrocardiographic monitoring is performed to obtain postexercise ABI as well as pain-free and maximum walking distances. In patients with PAD, ankle systolic BP measurements decrease during low levels of workload16; and postexercise ABI values are more sensitive for detecting PAD.17 Patients were determined to have PAD if they had a resting or postexercise ABI ≤0.9. Patients with PCA were identified on the basis of having an ABI >1.4, an ankle BP >255 mm Hg, or nonreproducible ankle BP measurements.

We used International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), code 428 (corresponding to the diagnosis of heart failure) to identify patients with heart failure within the time frame of 1 year, centered on the date of sample collection. The medical records of these patients were reviewed. The patients were excluded if they had an ejection fraction >50%, diastolic dysfunction grades 3 and 4, moderate or severe valvular abnormalities, or Framingham criteria for heart failure. Based on the previously described criteria, we excluded 7 patients with PCA and 25 patients with PAD, leaving 100 patients with PCA and 488 patients with PAD. For the 100 patients with PCA, we identified 300 age- and sex-matched cases with PAD.

Control Subjects

Controls without PAD or PCA belonged to the Prevalence of Asymptomatic Ventricular Dysfunction study, a random sample of Olmsted County residents ≥45 years (n=2042); these controls were identified using the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. The design and selection criteria of the Prevalence of Asymptomatic Ventricular Dysfunction study, and the characteristics of the Olmsted County population, have been previously described.18–20 Participants gave written consent and underwent phlebotomy and echocardiography, including an evaluation for systolic and diastolic dysfunction. Of the 2,042 total participants, 45 were excluded because of presence of heart failure by Framingham criteria,21 6 were excluded because of renal failure (serum creatinine >2.0 mg/dL),22,23 and 46 were excluded for having an abnormal ABI or a history of PAD. From the remaining 1,945 participants, we identified 300 age- and sex-matched controls for the patients with PCA.

Patient Characteristics

Medical records were reviewed to ascertain age, sex, body mass index, systolic BP, diastolic BP, conventional cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and smoking), history of CHD (ie, myocardial infarction, angina, coronary revascularization, or abnormal stress test or angiography result), cerebrovascular disease (ie, nonembolic ischemic stroke, >69% carotid artery stenosis, or history of carotid revascularization), and statin use.24 In addition, serum creatinine and lipid levels closest to the date of recruitment were extracted from the medical record.

NT Pro-BNP Assay

NT pro-BNP levels were measured in serum using a commercially available electrochemiluminescence immunoassay on a commercially available platform (Modular Analytics E170). The intra-assay coefficient of variation values were 1.1% and 1.3% at 122.4 and 3,629 pg/mL, respectively; and the interassay coefficient of variation values were 3.1% and 1.8% at 120.8 and 3635 pg/mL, respectively.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using computer software (SAS v 9.1.3). Continuous variables were expressed as mean±SD or median (interquartile range), whereas dichotomous variables were expressed as percentages. To reduce skewness, serum NT pro-BNP levels were log transformed before regression analyses. Multivariable linear regression analyses were used to identify determinants of serum NT pro-BNP levels in each of the 3 study groups from among age, sex, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, history of CHD or cerebrovascular disease, systolic BP, statin use, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and serum creatinine. Subsequently, we performed multivariable regression analyses to compare NT pro-BNP levels in the study groups after adjustment for variables associated with NT pro-BNP levels. We also applied the manufacturer-recommended cutoff values of NT pro-BNP levels and those used in the ProBNP Investigation of Dyspnea in the Emergency Department and International Collaborative of NT-proBNP studies25,26 to calculate the percentages of patients who had elevated NT pro-BNP levels in each of the study groups.

Results

Characteristics of the 3 groups (PCA, age- and sex-matched PAD, and control) are shown in Table 1. When compared with the age- and sex- matched PAD and control groups, patients with PCA had a greater prevalence of diabetes and a higher mean serum creatinine level. In multivariable regression models, variables associated with higher serum NT pro-BNP levels were as follows: PCA group, older age and higher serum creatinine level; PAD group, older age, lower total cholesterol level, and higher serum creatinine level; and controls, older age, female sex, history of CHD, and higher serum creatinine level (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics*

| Characteristics | PCA Group (n=100) | PAD Group (n=300) | Controls (n=300) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y† | 71±10 | 71±10 | 71±10 |

| Male sex | 70 (70) | 210 (70) | 210 (70) |

| BMI, kg/m2† | 29.5±5.9 | 28.5±4.6 | 28.0±4.8 |

| SBP, mm Hg† | 139±24 | 137±19 | 139±22 |

| DBP, mm Hg† | 70±11 | 71 ±10 | 74±10 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL† | 1.6±1.5 | 1.1±0.4 | 1.1±0.2 |

| eGFR, mL/min† | 57±24 | 65±18 | 61±13 |

| eGFR ≤60 mL/min | 53 (53) | 123 (41) | 143 (48) |

| Past or current smoker | 71 (71) | 255 (85) | 167 (56) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 55 (55) | 76 (25) | 41 (14) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL† | 180±54 | 189±45 | 198±36 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL† | 50±14 | 49±16 | 44±13 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL‡ | 126.5 (85.0–173.5) | 151.0 (104.0–207.0) | 126.5 (96.5–178.5) |

| Statin use | 46 (46) | 153 (51) | 69 (23) |

| Hypertension | 80 (80) | 227 (76) | 107 (36) |

| CHD | 59 (59) | 168 (56) | 67 (22) |

| CVD | 33 (33) | 112 (37) | 9 (3) |

| NT pro-BNP, pg/mL‡ | 417.0 (129.5–1,264.5) | 174.0 (73.4–452.5) | 112.7 (57.2–163.6) |

SI conversion factors: to convert serum creatinine to μmol/L, multiply by 88.4; total and HDL cholesterol to mmol/L, by 0.0259; triglycerides to mmol/L, by 0.0113; and NT pro-BNP to pmol/L, by 0.118.

BMI indicates body mass index; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Data are given as number (percentage) of each group unless otherwise indicated.

Data are given as mean±SD.

Data are given as median (25%–75% interquartile range).

Table 2.

Predictors of Serum NT Pro-BNP Levels in the Study Groups: Multivariable Regression Analyses*

| PCA Group (n=100) |

PAD Group (n=300) |

Controls (n=300) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β±SE | P Value | β±SE | P Value | β±SE | P Value |

| Age, y | 0.038±0.016 | 0.022 | 0.043±0.008 | <0.001 | 0.065±0.007 | <0.001 |

| Male sex | −0.593±0.350 | 0.094 | −0.283±0.168 | 0.094 | −0.696±0.160 | <0.001 |

| BMI | −0.020±0.026 | 0.457 | −0.013±0.016 | 0.405 | −0.022±0.014 | 0.108 |

| SBP, mm Hg | −0.007±0.006 | 0.233 | 0.003±0.004 | 0.422 | 0.005±0.003 | 0.124 |

| Smoking status | −0.138±0.351 | 0.695 | 0.035±0.208 | 0.866 | 0.032±0.130 | 0.806 |

| Hypertension | −0.165±0.396 | 0.678 | 0.219±0.184 | 0.236 | 0.182±0.137 | 0.183 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.329±0.354 | 0.356 | −0.119±0.170 | 0.484 | −0.043±0.178 | 0.811 |

| Statin use | 0.576±0.341 | 0.095 | −0.053±0.150 | 0.722 | −0.281±0.166 | 0.091 |

| CHD | 0.274±0.346 | 0.430 | 0.222±0.154 | 0.150 | 0.522±0.175 | 0.003 |

| CVD | −0.070±0.347 | 0.841 | 0.151 ±0.150 | 0.314 | −0.031 ±0.347 | 0.929 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | −0.003±0.003 | 0.323 | −0.005±0.002 | 0.008 | −0.003±0.002 | 0.114 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 0.004±0.012 | 0.733 | −0.002±0.005 | 0.749 | −0.003±0.005 | 0.952 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 0.402±0.103 | <0.001 | 0.849±0.201 | <0.001 | 0.656±0.285 | 0.022 |

Data given as β±SE.

BMI indicates body mass index; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

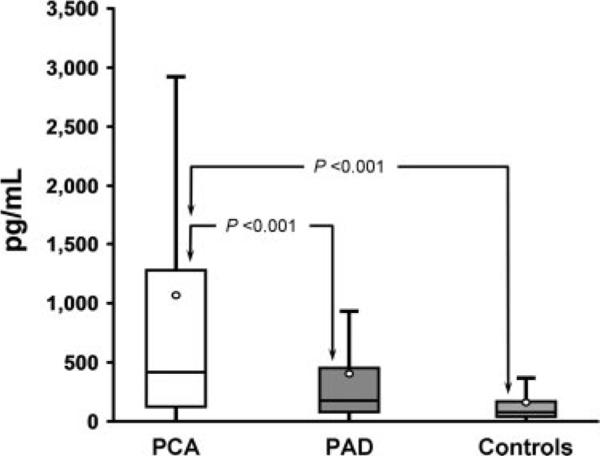

Patients in the PCA group had significantly higher levels of NT pro-BNP than in the age- and sex-matched PAD and control groups. Median (25%–75% interquartile range) NT pro-BNP levels were approximately 2.5-fold higher in the PCA group (417.0 [129.5–1,264.5] pg/mL) than in the PAD group (174.0 [73.4–452.5] pg/mL) and approximately 4-fold higher than in the control group (112.7 [57.2–163.6] pg/mL) (Figure 1). We compared NT pro-BNP levels in the 3 study groups using multivariable regression analyses that adjusted for the following variables: age, sex, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, history of CHD/cerebrovascular disease, statin use, and serum creatinine. NT pro-BNP levels were significantly higher in the PCA group than in the age- and sex-matched PAD and control groups (P<0.001 for both) (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Box-and-whisker plots comparing serum NT pro-BNP levels among the study groups. The circle represents the measured mean in each of the study groups (outliers have been removed for clarity of illustration).

Table 3.

Log NT Pro-BNP in the Study Groups: Multivariable Regression Analyses

| PCA vs PAD |

PCA vs Controls |

PAD vs Controls |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model* | β±SE | P Value | β±SE | P Value | β±SE | P Value |

| Unadjusted | 0.781±0.153 | <0.001 | 1.174±0.153 | <0.001 | 0.393±0.108 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 0.676±0.140 | <0.001 | 0.878±0.153 | <0.001 | 0.203±0.116 | 0.080 |

| 2 | 0.499±0.138 | <0.001 | 0.712±0.151 | <0.001 | 0.213±0.112 | 0.058 |

Data given as β±SE.

Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, cerebrovascular disease, coronary heart disease, diabetes mellitus, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, hypertension, and smoking; and model 2, adjusted for the variables in model 1 and also for serum creatinine level.

Among patients with PCA, 59% had NT pro-BNP levels higher than the manufacturer-recommended cutoff values (>125 pg/mL for patients <75 years and >450 pg/mL for patients ≥75 years) compared with 44% in the PAD group and 28% in the control group. We also used the cutoff values suggested in the ProBNP Investigation of Dyspnea in the Emergency Department and International Collaborative of NT-proBNP studies, which consist of an age-independent rule-out value of 300 pg/mL and age-stratified rule-in values of 450, 900, and 1,800 pg/mL for ages <50, 50 to 75, and >75 years, respectively.25,26 Among patients with PCA, 56% had serum NT pro-BNP levels higher than the previously described rule-out value compared with 33% and 4% in the PAD and control groups, respectively. Moreover, 27% of patients with PCA had NT pro-BNP levels higher than the age-stratified rule-in values compared with 6% in the PAD group and 2% in the control group.

Discussion

Patients with PCA and an elevated ABI represent a distinct subset of PAD. Poor compressibility of the lower-extremity arteries is the result of medial arterial calcification, which typically circumferentially affects the arterial wall27 and results in an artifactually high ankle BP and an elevated ABI (>1.4). Medial arterial calcification is associated with diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and an increased risk for adverse cardiovascular events and lower-extremity amputation.27,28 Most, but not all, patients with PCA have coexisting atherosclerosis, as evident by abnormal Doppler signals and/or low toe-brachial indexes.29 In the present study, we report, for the first time to our knowledge, that serum NT pro-BNP levels are significantly higher in patients with PCA than in those with PAD and controls, even after adjustment for potential confounding variables. In patients with PCA, serum NT pro-BNP levels were approximately 2.5-fold higher than levels in age- and sex-matched patients with PAD and approximately 4-fold higher than levels in age- and sex-matched controls. Our findings suggest that patients with PCA have increased hemodynamic and myocardial stress that is greater than in patients with diffuse atherosclerosis (ie, patients with PAD who have an ABI ≤0.9).

Increased NT Pro-BNP Levels in the Setting of PAD

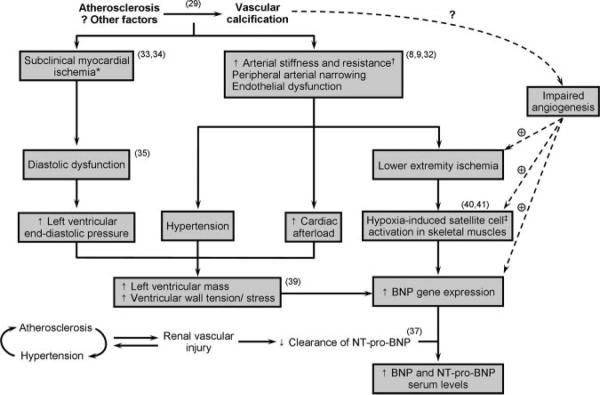

Patients with PAD had higher levels of NT pro-BNP than age- and sex-matched controls, although the difference was attenuated after adjustment for additional covariates. However, when all of the patients with PAD identified during the study period (n=488; aged 67±10 years; 64% men) were compared with age- and sex-matched controls from the community (n=976), the difference in median NT pro-BNP levels (139 versus 77 pg/mL) was highly significant (P<0.001) and independent of potential confounders (analyses not shown). These findings are consistent with the results of previous smaller studies12,30 and suggest greater hemodynamic stress in patients with PAD. Several factors may contribute to increased circulating levels of NT pro-BNP in patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease, including luminal narrowing and endothelial dysfunction,27,31,32 leading to increased arterial resistance and cardiac afterload (Figure 2). Also, such patients often have concomitant coronary atherosclerosis leading to myocardial ischemia, diastolic dysfunction, and increased left ventricular end-diastolic filling pressures.8,33,34 The increased afterload, ventricular stiffness, and filling pressures will eventually lead to increased ventricular wall stress/tension and NT pro-BNP secretion.35,36 An additional mechanism may be renal vascular injury and impaired clearance of NT pro-BNP in the setting of diffuse atherosclerosis.37

Figure 2.

Potential pathways underlying elevated serum NT pro-BNP in patients with medial arterial calcification and PCA. *Subclinical myocardial ischemia may actually be the initial cause of increased BNP gene transcription and expression in cardiac myocytes. †Arterial stiffness is likely to be increased in patients with PCA. ‡Satellite cells are the myogenic stem cells responsible for skeletal muscle regeneration.

Increased Arterial Stiffness in Patients With Medial Arterial Calcification

Experimentally induced medial arterial calcification in rats results in increased arterial stiffness.38 We are not aware of reports of direct measurement of arterial stiffness in patients with PCA; however, arterial stiffness is likely increased in patients with an ABI >1.4, leading to increased hemodynamic and myocardial stress. Indirect support for increased arterial stiffness in patients with PCA comes from a study39 that found left ventricular mass to be higher in participants with PCA than in patients with PAD (ABI ≤0.9) and subjects without PAD (ABI: 0.9 to 1.4), independent of potential confounders.39 The researchers also found ankle systolic BP to correlate with left ventricular mass. Our study extends these findings by demonstrating increased serum levels of NT pro-BNP, a humoral surrogate of increased arterial stiffness and hemodynamic stress, in patients with PCA. We did not find a correlation between ankle systolic BP and NT pro-BNP levels in our study (analyses not shown). Ankle BP measurements in patients with PCA are poorly reproducible and may not be reliable for use in statistical analyses.

Peripheral Production of BNP

Many patients with PCA and PAD have NT pro-BNP levels similar to those in patients with heart failure. Because we excluded subjects with a history of overt heart failure based on medical record review, this raises the possibility that peripheral mechanisms may contribute to increased levels of NT pro-BNP. Kuhn et al40 showed increased transcription and production of BNP in satellite cells within the ischemic skeletal muscle 3 days after femoral artery ligation in mice. The peripheral BNP production was also coupled with increased angiogenesis in the affected limb.40 Another study41 demonstrated impaired angiogenesis after hindlimb ischemia in mice lacking guanylyl cyclase-A, which plays a pivotal role in BNP signaling pathways. These recent studies suggest that increased production of peripheral BNP may be a response to stimulate angiogenesis in the ischemic skeletal muscles of patients with PCA and PAD.

Increased NT Pro-BNP Levels in Patients With PCA

Medial arterial calcification is distinct from the intimal calcification that occurs in atherosclerotic lesions; however, these 2 conditions may coexist,42 leading to greater morbidity and mortality than any one condition by itself. Based on decreased toe-brachial indexes, one study29 concluded that 60% of patients with medial arterial calcification have concomitant atherosclerosis. Of the 100 patients with PCA in our study, only 13 had normal lower-extremity arterial Doppler signals. However, NT pro-BNP levels were also elevated in this group (median, 274 pg/mL; mean, 911 pg/mL), suggesting that NT pro-BNP elevation in patients with PCA may be independent of concomitant atherosclerosis. In patients with PCA, the presence of medial arterial calcification may impede vascular regeneration, delay angiogenesis, and prolong ischemia in the affected skeletal muscles, resulting in an even greater stimulus for BNP production from satellite cells. We have summarized various pathways that may collectively increase serum NT pro-BNP levels in patients with PCA and PAD (Figure 2).

Clinical Implications

NT pro-BNP levels were predictive of mortality in patients with PAD in 2 previous studies13,14; we can speculate that NT pro-BNP is similarly predictive of adverse events in patients with PCA. However, the utility of NT pro-BNP as a predictor of mortality and adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with PCA needs further investigation. The potential angiogenic role of natriuretic peptides led Park et al43 to evaluate the therapeutic effects of recombinant human atrial natriuretic peptide in 13 patients with PAD. A significant improvement in the ABI values, intermittent claudication, rest pain, and ulcer healing was noted in this small pilot study.43 Whether pharmacological modulation of the natriuretic peptide system will have beneficial effects in patients with PCA or PAD needs further investigation, including randomized controlled trials.

Study Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate elevated NT pro-BNP levels in patients with medial arterial calcification and PCA when compared with age- and sex-matched patients with PAD and controls. Our study identified patients with PCA and PAD from the noninvasive vascular laboratory of a tertiary care center, and some degree of referral bias may be present. The cross-sectional nature of our study precludes us from making inferences about the temporal relationship between onset of elevated NT pro-BNP levels and PCA or PAD. Not all PCA may be the result of medial arterial calcification, and we did not have foot radiographs available to confirm the presence of medial arterial calcification in patients with PCA.

In conclusion, serum NT pro-BNP levels were significantly higher in patients with medial arterial calcification and PCA than in patients with PAD and controls without a history of PAD. Nearly 60% of patients with PCA in our study had serum NT pro-BNP levels higher than the manufacturer-recommended levels to rule out heart failure. Although greater hemodynamic and myocardial stress as the result of increased arterial stiffness is a plausible mechanism underlying our findings, BNP secretion by ischemic skeletal muscles has been recently reported40 and may also be operative. Whether NT pro-BNP levels predict mortality and adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with PCA needs confirmation in future studies. Finally, the therapeutic potential of BNP analogues in patients with PCA and PAD may be the subject of investigation in future clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

We thank Vicki M. Schmidt, BS, for her help with manuscript preparation.

Sources of Funding This study was supported by grants HL-81331, HL-36634, and UL1-RR024150 (Center for Translational Science Activities) from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.

Footnotes

Disclosures None.

References

- 1.Monckeberg J. Uber die reine Mediaverkalkung der Extremitatenarterien und ihr verhalten zur Arteriosklerose. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat. 1902;171:141–167. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niskanen L, Siitonen O, Suhonen M, Uusitupa MI. Medial artery calcification predicts cardiovascular mortality in patients with NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:1252–1256. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.11.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Everhart JE, Pettitt DJ, Knowler WC, Rose FA, Bennett PH. Medial arterial calcification and its association with mortality and complications of diabetes. Diabetologia. 1988;31:16–23. doi: 10.1007/BF00279127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Resnick HE, Foster GL. Prevalence of elevated ankle-brachial index in the United States 1999 to 2002. Am J Med. 2005;118:676–679. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Resnick HE, Lindsay RS, McDermott MM, Devereux RB, Jones KL, Fabsitz RR, Howard BV. Relationship of high and low ankle brachial index to all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality: the Strong Heart Study. Circulation. 2004;109:733–739. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000112642.63927.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melton LJ, III, Macken KM, Palumbo PJ, Elveback LR. Incidence and prevalence of clinical peripheral vascular disease in a population-based cohort of diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 1980;3:650–654. doi: 10.2337/diacare.3.6.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newman AB, Shemanski L, Manolio TA, Cushman M, Mittelmark M, Polak JF, Powe NR, Siscovick D, Cardiovascular Health Study Group Ankle-arm index as a predictor of cardiovascular disease and mortality in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:538–545. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.3.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atkinson J. Age-related medial elastocalcinosis in arteries: mechanisms, animal models, and physiological consequences. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:1643–1651. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90476.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toussaint ND, Kerr PG. Vascular calcification and arterial stiffness in chronic kidney disease: implications and management. Nephrology (Carlton) 2007;12:500–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2007.00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamamoto K, Burnett JC, Jr, Jougasaki M, Nishimura RA, Bailey KR, Saito Y, Nakao K, Redfield MM. Superiority of brain natriuretic peptide as a hormonal marker of ventricular systolic and diastolic dysfunction and ventricular hypertrophy. Hypertension. 1996;28:988–994. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.28.6.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKie PM, Burnett JC., Jr. B-type natriuretic peptide as a biomarker beyond heart failure: speculations and opportunities. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:1029–1036. doi: 10.4065/80.8.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Svensson P, de Faire U, Niklasson U, Hansson LO, Ostergren J. Plasma NT-proBNP concentration is related to ambulatory pulse pressure in peripheral arterial disease. Blood Press. 2005;14:99–106. doi: 10.1080/08037050510008931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mueller T, Dieplinger B, Poelz W, Endler G, Wagner OF, Haltmayer M. Amino-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide as predictor of mortality in patients with symptomatic peripheral arterial disease: 5-year follow-up data from the Linz Peripheral Arterial Disease Study. Clin Chem. 2009;55:68–77. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.108753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shadman R, Allison MA, Criqui MH. Glomerular filtration rate and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide as predictors of cardiovascular mortality in vascular patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2172–2181. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marz W, Tiran B, Seelhorst U, Wellnitz B, Bauersachs J, Winkelmann BR, Boehm BO. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide predicts total and cardiovascular mortality in individuals with or without stable coronary artery disease: the Ludwigshafen Risk and Cardiovascular Health Study. Clin Chem. 2007;53:1075–1083. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.075929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stahler C, Strandness DE., Jr. Ankle blood pressure response to graded treadmill exercise. Angiology. 1967;18:237–241. doi: 10.1177/000331976701800406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ouriel K, McDonnell AE, Metz CE, Zarins CK. Critical evaluation of stress testing in the diagnosis of peripheral vascular disease. Surgery. 1982;91:686–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Redfield MM, Jacobsen SJ, Burnett JC, Jr, Mahoney DW, Bailey KR, Rodeheffer RJ. Burden of systolic and diastolic ventricular dysfunction in the community: appreciating the scope of the heart failure epidemic. JAMA. 2003;289:194–202. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Costello-Boerrigter LC, Boerrigter G, Redfield MM, Rodeheffer RJ, Urban LH, Mahoney DW, Jacobsen SJ, Heublein DM, Burnett JC., Jr. Amino-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide and B-type natriuretic peptide in the general community: determinants and detection of left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Senni M, Tribouilloy CM, Rodeheffer RJ, Jacobsen SJ, Evans JM, Bailey KR, Redfield MM. Congestive heart failure in the community: a study of all incident cases in Olmsted County, Minnesota, in 1991. Circulation. 1998;98:2282–2289. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.21.2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho KK, Anderson KM, Kannel WB, Grossman W, Levy D. Survival after the onset of congestive heart failure in Framingham Heart Study subjects. Circulation. 1993;88:107–115. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, Leip EP, Omland T, Wolf PA, Vasan RS. Plasma natriuretic peptide levels and the risk of cardiovascular events and death. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:655–663. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kistorp C, Raymond I, Pedersen F, Gustafsson F, Faber J, Hildebrandt P. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, C-reactive protein, and urinary albumin levels as predictors of mortality and cardiovascular events in older adults. JAMA. 2005;293:1609–1616. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kullo IJ, Fan J, Pathak J, Savova GK, Ali Z, Chute CG. Leveraging informatics for genetic studies: use of the electronic medical record to enable a genome-wide association study of peripheral arterial disease. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2010;17:568–574. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2010.004366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Januzzi JL, Jr, Camargo CA, Anwaruddin S, Baggish AL, Chen AA, Krauser DG, Tung R, Cameron R, Nagurney JT, Chae CU, Lloyd-Jones DM, Brown DF, Foran-Melanson S, Sluss PM, Lee-Lewandrowski E, Lewandrowski KB. The N-terminal Pro-BNP Investigation of Dyspnea in the Emergency Department (PRIDE) Study. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:948–954. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Januzzi JL, van Kimmenade R, Lainchbury J, Bayes-Genis A, Ordonez-Llanos J, Santalo-Bel M, Pinto YM, Richards M. NT-proBNP testing for diagnosis and short-term prognosis in acute destabilized heart failure: an international pooled analysis of 1256 patients: the International Collaborative of NT-proBNP Study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:330–337. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Towler D. Vascular calcification: a perspective on an imminent disease epidemic. IBMS BoneKEy. 2008;5:41–58. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lehto S, Niskanen L, Suhonen M, Ronnemaa T, Laakso M. Medial artery calcification: a neglected harbinger of cardiovascular complications in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16:978–983. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.8.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suominen V, Rantanen T, Venermo M, Saarinen J, Salenius J. Prevalence and risk factors of PAD among patients with elevated ABI. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35:709–714. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montagnana M, Lippi G, Fava C, Minuz P, Santonastaso CL, Arosio E, Guidi GC. Ischemia-modified albumin and NT-prohormone-brain natriuretic peptide in peripheral arterial disease. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2006;44:207–212. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2006.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davignon J, Ganz P. Role of endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2004;109:III27–III32. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131515.03336.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dao HH, Essalihi R, Bouvet C, Moreau P. Evolution and modulation of age-related medial elastocalcinosis: impact on large artery stiffness and isolated systolic hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;66:307–317. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Her K, Choi C, Park Y, Shin H, Won Y. Concomitant peripheral artery disease and asymptomatic coronary artery disease: a management strategy. Ann Vasc Surg. 2008;22:649–656. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDermott MM, Liu K, Criqui MH, Ruth K, Goff D, Saad MF, Wu C, Homma S, Sharrett AR. Ankle-brachial index and subclinical cardiac and carotid disease: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:33–41. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lester SJ, Tajik AJ, Nishimura RA, Oh JK, Khandheria BK, Seward JB. Unlocking the mysteries of diastolic function: deciphering the Rosetta Stone 10 years later. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:679–689. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rubattu S, Sciarretta S, Valenti V, Stanzione R, Volpe M. Natriuretic peptides: an update on bioactivity, potential therapeutic use, and implication in cardiovascular diseases. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:733–741. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeFilippi C, van Kimmenade RR, Pinto YM. Amino-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide testing in renal disease. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niederhoffer N, Lartaud-Idjouadiene I, Giummelly P, Duvivier C, Peslin R, Atkinson J. Calcification of medial elastic fibers and aortic elasticity. Hypertension. 1997;29:999–1006. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.29.4.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ix JH, Katz R, Peralta CA, de Boer IH, Allison MA, Bluemke DA, Siscovick DS, Lima JA, Criqui MH. A high ankle brachial index is associated with greater left ventricular mass MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuhn M, Volker K, Schwarz K, Carbajo-Lozoya J, Flogel U, Jacoby C, Stypmann J, van Eickels M, Gambaryan S, Hartmann M, Werner M, Wieland T, Schrader J, Baba HA. The natriuretic peptide/guanylyl cyclase: a system functions as a stress-responsive regulator of angiogenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2019–2030. doi: 10.1172/JCI37430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tokudome T, Kishimoto I, Yamahara K, Osaki T, Minamino N, Horio T, Sawai K, Kawano Y, Miyazato M, Sata M, Kohno M, Nakao K, Kangawa K. Impaired recovery of blood flow after hind-limb ischemia in mice lacking guanylyl cyclase-A, a receptor for atrial and brain natriuretic peptides. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1516–1521. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.187526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Demer LL, Tintut Y. Vascular calcification: pathobiology of a multi-faceted disease. Circulation. 2008;117:2938–2948. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park K, Itoh H, Yamahara K, Sone M, Miyashita K, Oyamada N, Sawada N, Taura D, Inuzuka M, Sonoyama T, Tsujimoto H, Fukunaga Y, Tamura N, Nakao K. Therapeutic potential of atrial natriuretic peptide administration on peripheral arterial diseases. Endocrinology. 2008;149:483–491. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]