Abstract

Background

Bile reflux contributes to the development of esophageal injury and neoplasia. MUC5AC mucin is absent in the normal squamous epithelium of the esophagus but strongly expressed in Barrett’s esophagus (BE). The aim of this study was to determine whether and how bile acids influence the expression of MUC5AC in the esophagus.

Methods

MUC5AC expression was studied by immunohistochemistry and immunoblotting in human tissues, tissues from a rat model of BE, and in SKGT-4 cultured esophageal epithelial cells. MUC5AC transcription was studied by real-time PCR and transient transfection assays.

Results

MUC5AC was absent from normal squamous epithelium but present in 100% of Barrett’s specimens and in 61.5% of human esophageal adenocarcinoma tissues examined. MUC5AC protein expression was induced to a greater degree by conjugated bile acids than by unconjugated bile acids, and this occurred at the transcriptional level. In the rat reflux model, MUC5AC mucin was abundantly expressed in tissues of BE stimulatesd by duodenoesophageal reflux. Conjugated bile acids induced AKT phosphorylation in SKGT-4 cells, but had no effects on ERK1/2, JNK, and P-38 kinase phosphorylation. The PI3K inhibitor LY294002 and a dominant-negative AKT construct prevented the induction of MUC5AC by conjugated bile acids. Transactivation of AP-1 by conjugated bile acids coincided with MUC5AC induction, and co-transfection with a dominant-negative AP-1 vector decreased MUC5AC transcription and its induction.

Conclusions

Conjugated bile acids in the bile refluxate contribute to MUC5AC induction in the esophagus. This occurs at the level of transcription, and involves activation of the PI3K/AKT/AP-1 pathway.

Keywords: MUC5AC mucin, bile reflux, PI3K pathway, AP-1, Barrett’s Esophagus

Introduction

Esophageal cancer is the seventh leading cause of cancer death among men in the U.S1. During the past several decades, the incidence of adenocarcinoma in the esophagus has risen at an alarming rate in western countries, and has exceeded that of squamous cell carcinoma2, 3. Most esophageal adenocarcinomas (EA) arise from Barrett’s esophagus 4, a condition in which metaplastic columnar epithelium replaces the normal stratified squamous epithelium.5

Gastroesophageal reflux of acid and bile is the predominant initiating factor in Barrett’s metaplasia and its progression to EA6. Bile reflux is particularly common in individuals with gastroesophageal reflux disease who subsequently develop Barrett’s esophagus 7, 8. Barrett’s esophagus also develops secondary to bile reflux in patients who have undergone total gastrectomy 9. Consistent with this observation, Barrett’s esophagus is followed by EA in a rat model that uses esophagojejunostomy to bypass exposure to acid reflux from the stomach 10. In this model, enteroesophageal reflux produces EA in 48% of rats in the absence of exposure to any exogenous carcinogen 11. The precise mechanisms by which duodenal reflux causes esophageal injury and leads to metaplasia and predisposes to EA is uncertain.

Mucins, are large, heavily glycosylated proteins located at the surface of many epithelia and play an important role in protecting epithelial cells12. In normal esophageal tissue, secreted mucins protect the mucosa against potential injuries such as the reflux of gastroduodenal contents, including acid and bile 4. Mucin genes are expressed in a site-specific manner throughout the gastrointestinal tract. In the normal esophagus, MUC1 and MUC4 are the main mucin genes expressed in the stratified squamous epithelium, whereas MUC5B is expressed in the submucosal glands 13. The MUC5AC gene is expressed in the stomach and in tracheobronchial cells, but not in the normal esophagus13, 14. De novo expression of the MUC5AC and the MUC2 genes (an intestinal mucin) has been observed in Barrett’s esophagus 13, 15–17. The associated risk factors, the mechanisms controlling the expression of MUC5AC mucin in Barrett’s esophagus, and the pathological significance of this mucin in Barrett’s columnar epithelium are not clearly understood.

We hypothesized that bile acids in the gastroesophageal refluxate contribute to the formation of Barrett’s phenotype, including the ectopic expression of MUC5AC mucin. We sought to determine which bile acids are responsible for MUC5AC expression and the molecular mechanisms involved.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were obtained from Life Technologies, Inc. (Grand Island, NY). LY294002 was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Conjugated (GC, TC, TCDC, GCDC, TDC) and unconjugated (CD and DC) bile acids were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). ECL-chemiluminescence reagents were purchased from Amersham-Pharmacia (Piscataway, NJ). Total and phosphorylated ERK-1/2 antibodies, phosphorylated AKT antibodies, and phosphorylated JNK and P-38 antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). MUC5AC monoclonal antibody (CLH2 clone) was obtained from Novocastra Laboratories Ltd (Newcastle, UK). Mouse anti-MUC5AC antibody (clone SPM488) for rat tissues was obtained from Spring Bioscience (Fremont, CA). MUC5AC polyclonal antibody HO8 was a gift from Dr. Christopher M. Evans at The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center.

Cell Culture

Human SKGT-4 EA cells, derived from well-differentiated adenocarcinoma arising in Barrett’s esophagus,18 were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μl/mL streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. Treatments with vehicle (0.1% ethanol) or bile acids were performed in 0.5% FBS. Cytotoxicity was assessed by cell numbers, trypan blue exclusion, and the MTT assay (Promega, Madison, WI). For the trypan blue analysis, after treatment with bile acids for 16 hours, cells were mixed 1:1 with 0.4% trypan blue and examined for dye exclusion.

Protein Isolation and Immunoblot Analysis

Cells were lysed in buffer containing 30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaF, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 2 mM orthovanadate, 1% Triton X-100, 1% NP-40, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and one mini-tablet protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics Corp, Indianapolis, IN). Protein concentration of the supernatant was determined using the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Equal amounts of protein were subjected to electrophoresis on either 3–8% Tris-acetate gradient gels for MUC5AC detection or 10% Tris-glycine gels for detection of other proteins. After gel electrophoresis and transfer to nitrocellulose, the membranes were stained with 0.5% Ponceau S with 1% acetic acid to confirm equal loading and transfer efficiency. Western blots were performed by incubating membranes at room temperature for 1 hour in a blocking solution containing 5% non-fat dry milk and 0.1% Tween-20 in Tris-buffered saline (10 mM Tris-HCl with 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.6), probing with specific primary antibodies, washing with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20, and probing with secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. Immunoreactive bands were visualized by chemiluminescence..

Plasmids, Transient Transfection, and Luciferase Reporter Assays

A human MUC5AC promoter construct19, containing the 3.7 kb MUC5AC 5′-flanking region fused to a luciferase reporter gene was provided by Dr. Ja Seok Koo at the University of Texas M. D Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC). Dominant-negative AP-1 (blunted TAM67) 20 and the AP-1 promoter-luciferase reporter 21 were provided by Dr. Shrikanth A. Reddy and Dr. Jonathan Kurie (MDACC). The cDNA plasmid for the dominant-negative mutant of AKT (AKT AAA) was provided by Dr. Dimpy Koul (MDACC) 22. Plasmids were prepared using the Genopure Plasmid Midi Kit (Roche Diagnostics). The beta-galactosidase expression vector pCH110 (Amersham-Pharmacia, Arlington Heights, IL) was used to normalize transfection efficiency.

For transient transfection studies, SKGT-4 cells were seeded at a concentration of 4 × 105 cells per well in 6-well plates. After overnight culture, cells were transfected with DNA (1 μg of MUC5AC or AP-1-luciferase reporter plasmid and 0.2 μg of pCH110) mixed with 3 μl of FuGENE 6 (Roche Diagnostics). Cells were then cultured for an additional 24 hours and harvested for the measurement of luciferase activity, which was rendered in relative light units normalized to beta-galactosidase using the Promega luciferase assay system (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) with a TD-20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA). Values shown represent the mean and standard deviation of the results from at least three independent experiments.

Quantitative Real-time RT-PCR Analysis of MUC5AC mRNA Level

MUC5AC mRNA levels were measured with an Applied Biosystems Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System using the TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as described previously 23.

The TaqMan probes and primers used for MUC5AC (assay identification number Hs00873638-ml) were assay-on-demand gene expression products (Applied Biosystems). The human β-actin gene was used as the endogenous control (Applied Systems, Hs99999903-ml). The MUC5AC probe was labeled using the reporter dye FAM, and the β-actin internal control was labeled with a different reporter dye VIC at the 5′ end. A nonfluorescent quencher and the minor groove binder were linked at the 3′ end of the probe as quenchers. All samples were analyzed in triplicate. Amplification data were analyzed with Applied Biosystems Prism Sequence Detection Software Version 2.1. For relative quantification, the expression of MUC5AC was normalized against β-actin and rendered as the ratio of the expression of each target gene mRNA to the expression of each housekeeping gene mRNA.

Rat Model of Barrett’s Esophagus

Six-week old male Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN) and housed under standard laboratory conditions. Levrat’s esophagojejunostomy technique was used to induce enteroesophageal reflux and was performed as previously described.24 The animal care committee (IACUC) at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, approved this study.

Rats were euthanized after 50 weeks and sacrificed. The esophagus was cut at the level of larynx and 2 mm above the anastomosis site and opened longitudinally. The esophagus was fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 hours and then transferred to 80% ethanol. The fixed esophagus was longitudinally divided into 6–8 well-oriented tissue slices, each slice representing the entire length and full depth of the esophagus but ≤1 mm wide. Slices were processed and fixed in paraffin to maintain tissue orientation for histopathologic analysis.

Histopathological Analysis and Immunohistochemistry

Tissue samples consisting of 28 cases of normal esophageal epithelium, 34 cases of Barrett’s esophagus, and 28 cases of EA were obtained from individuals undergoing esophagogastroduodenoscopy at MDACC under an IRB approved protocol. There were paired specimens of normal esophageal epithelium, Barrett’s esophagus and EA from 22 individuals. Patterns of expression were also verified in 6 additional cases with paired specimens of Barrett’s esophagus and adenocarcinoma, and 6 cases containing paired specimens of Barrett’s esophagus and normal epithelium without adenocarcinoma. Samples were fixed in PBS-buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Hematoxylin-and-eosin–stained sections (6 μm) were used to classify tissue types. Human tissue sections were immunostained by the avidin-biotin-complex method 25 using antibody against MUC5AC apomucin (CLH2, mouse monoclonal antibody, dilution 1:100). Expression of MUC5AC was scored using a previously validated semiquantitative scoring system that takes into account tissue heterogeneity and is subject to statistical analysis 26.

For the rat tissue studies, histopathological analysis was carried out on tissue sectioned into 6-μm slices and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. A diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus was suspected when columnar metaplasia intestinal-type goblet cells were found and confirmed on the basis of mucin characteristics plus staining with periodic acid-Schiff and Alcian blue (pH 2.5). Immunohistochemistry studies were performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections (6 μm) with antibodies against MUC5AC antibodies (mouse monoclonal antibody; dilution 1:100; HO8 polyclonal antibody, dilution 1:200) after antigens were retrieved using 10 mM sodium citrate buffer as previously described 26.

Results

MUC5AC Mucin Expression in Human Esophageal Mucosa, Barrett’s Esophagus, and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma

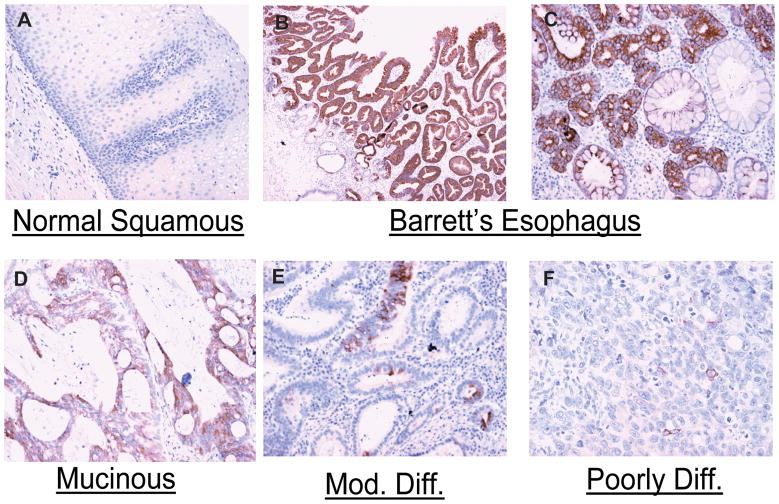

To clarify the pattern of MUC5AC expression in normal human esophageal mucosa, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma, we performed immunohistochemistry to detect MUC5AC apomucin in paired human tissue specimens. MUC5AC was not detected in any of the specimens of normal squamous mucosa (Fig 1.A). In contrast, MUC5AC was strongly expressed in all 34 specimens of Barrett’s esophagus, with an average score of 2.897 (Fig. 1. B, C). MUC5AC expression was decreased in almost two thirds (61.5%) of esophageal adenocarcinoma tissues compared to paired samples of Barrett’s esophagus, with an average score of 0.96 (Fig. 1. D, E, F). MUC5AC was extensively expressed on the surface epithelium in Barrett’s esophagus but was also expressed in the deeper parts of glandular structures and in both columnar non–goblet cells and goblet cells (Fig. 1B, C)., MUC5AC was sparsely present in cancer specimens, and showed a progressive decrease in intensity with poorer differentiation (Fig. 1E, F).

Figure 1. MUC5AC expression in human esophageal mucosa, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma tissues.

MUC5AC mucin was detected in tissues of normal esophageal epithelium (A), Barrett’s esophagus (B, C), esophageal mucinous adenocarcinoma (D) and esophageal adenocarcinoma (E, F) by immunohistochemistry as described in materials and methods.

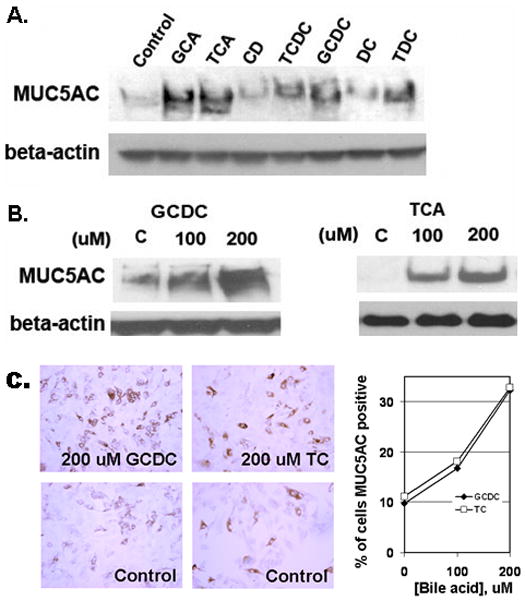

Conjugated Bile Acids are Potent Inducers of MUC5AC Mucin in Human Esophageal Epithelia Cells

Since MUC5AC mucin was present in all Barrett’s esophageal specimens but absent in normal squamous epithelium, and since bile reflux is a major risk factor for Barrett’s esophagus, we sought to determine if bile acids and their conjugates are responsible for the induction of MUC5AC expression in the esophagus. SKGT-4 cells were treated with conjugated and unconjugated bile acids for 16 hours at a concentration of 200 μM, which has been reported to be a physiological concentration in esophageal refluxate 27, 28. Cell lysate was prepared, subjected to electrophpresis, and and immunoblotted with a specific antibody (CLH2) against MUC5AC apomucin. MUC5AC apomucin expression was modified only slightly after treatment with the unconjugated bile acids CD and DC (Figure 2A). However, a strong increase in MUC5AC expression was observed after treatment with the glyco- or tauro-conjugated bile acids GC, TC, TCDC, GCDC, and TDC. In order to confirm this induction of MUC5AC expression by conjugated bile acids, cells were treated with different doses of GCDC and TC, which are the predominant bile acids in gastroesophageal refluxate. Both GCDC and TC caused a dose-dependent induction of MUC5AC apomucin expression in SKGT-4 cells (Figure 2B). Immunocytochemical staining for MUC5AC apomucin in cells plated in chamber slides also confirmed the increase in MUC5AC expression induced by GCDC and TC, and this increase was likewise dose dependent (Figure 2C). Bile acid treatment did not, under the conditions used, induce change in the morphology of the cells (Fig. 2C) or affect cell viability.

Figure 2. Conjugated bile acids induce MUC5AC mucin expression in human esophageal epithelial cells.

(A) SKGT-4 cells were treated with 200 μM of bile acids (GCA, TCA, CD, TCDC, GCDC, DC, and TDC) for 16–24 h. Immunoblots were performed to determine MUC5AC expression. (B) SKGT-4 cells were stimulated with increasing concentrations of GCDC and TCA and immunoblots were performed as in (A). (C) MUC5AC immunostaining of cultured SKGT-4 cells treated with GCDC and TCA at 200 μM for 16 hours as compared to control (left panel). Percent of MUC5AC positive cells treated with GCDC and TCA at 100 and 200 μM is depicted in the right panel.

Conjugated Bile Acids Induce MUC5AC Transcription in Esophageal Epithelial Cells

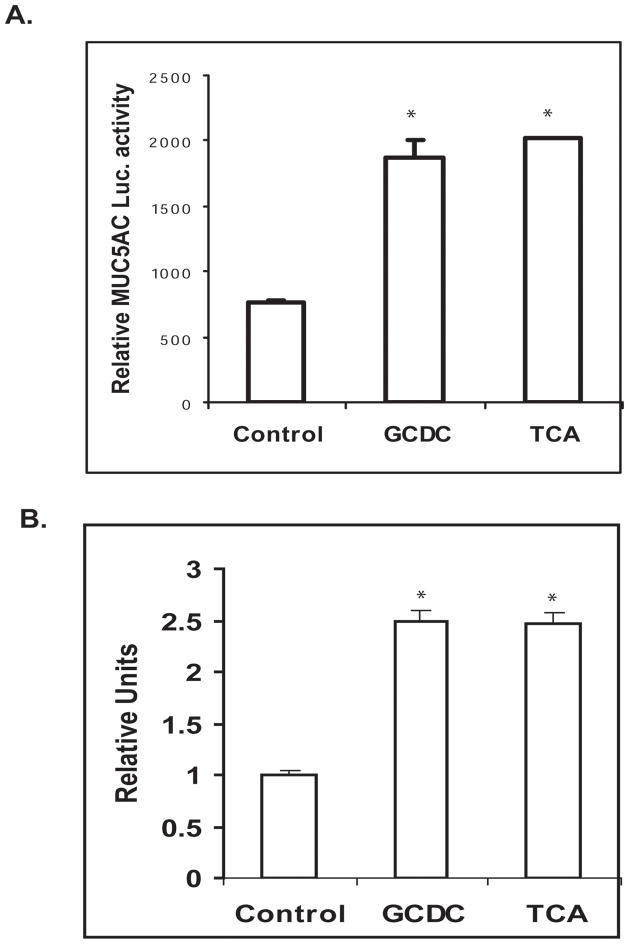

In order to determine if the induction of MUC5AC by conjugated bile acids occurs at the transcriptional level, cells were transiently transfected with the human MUC5AC promoter-luciferase construct. Treatment with GCDC and TC at concentration of 200 μM for 16 hours led to a greater than two-fold increase in MUC5AC promoter activity (Fig. 3A). This increase in the transcription of the MUC5AC gene was confirmed by real-time PCR in SKGT-4 cells treated with GCDC and TC (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Conjugated bile acids induce MUC5AC transcription in human esophageal epithelial cells.

(A) SKGT-4 cells were cotransfected with 1 μg of human MUC5AC promoter plus 0.2 mg of pSV-β-gal and treated with 200 μM GCDC and TCA. Luciferase reporter activities were measured after 16 h. Values represent the mean and standard deviation of triplicate experiments. * p<0.01 vs control. (B). MUC5AC was detected by qantitative real time PCR in SKGT-4 cells treated with 200 μM GCDC and TCA. Values represent the mean and standard deviation of triplicate experiments. * p<0.01 vs control.

Signaling Mechanisms by Which Conjugated Bile Acids Induce MUC5AC

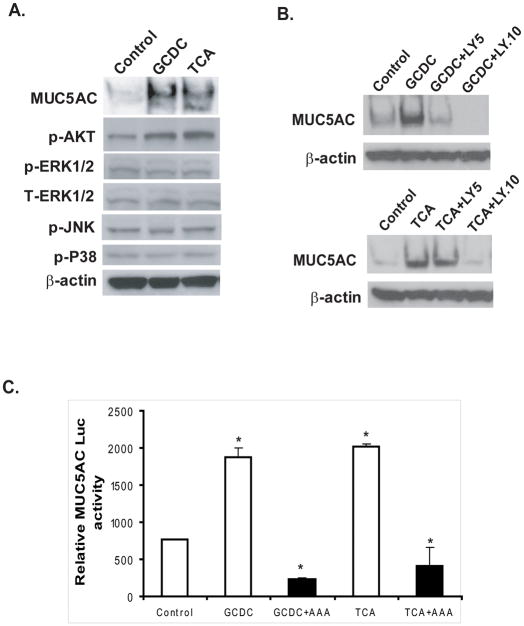

Previous studies have implicated phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K) as important for the bile acid-mediated activation of MUC4 mucin. We therefore used phospho-specific antibodies, pharmacologic and genetic approaches to identify the intracellular signaling pathways responsible for the induction of MUC5AC expression by conjugated bile acids. Phosphorylation of AKT was induced by the conjugated bile acids GCDC and TCA at concentration of 200 μM, (corresponding to induction of MUC5AC expression), while no change in the phosphorylation of the MAP kinases ERK1/2, JNK, and P-38 occurred under these conditions (Figure 4A). Ly294002, a specific inhibitor of PI3K, blocked GCDC- or TCA-induced MUC5AC expression at concentrations of 5 μM and 10 μM, and this reduction was dose dependent (Fig. 4B). When the cDNA plasmid for the dominant-negative mutant of AKT (AKT AAA) was co-transfected with the MUC5AC-promoter-luciferase construct into SKGT-4 cells, expression of the dominant-negative mutant of AKT (AKT AAA) completely blocked the MUC5AC transcription induced by GCDC or TCA (Figure 4C). This further suggests that the PI3K-AKT pathway is involved in the induction of MUC5AC expression by the conjugated bile acids GCDC and TCA.

Figure 4. The PI3K/AKT pathway mediates MUC5AC induction by conjugated bile acids GCDC and TCA.

(A) SKGT-4 cells were treated with 200 μM of conjugated bile acids GCDC and TCA for 16–24 h, and immunoblots were performed with antibodies against phospho-AKT (S473), phospho-ERK1/2, phospho-JNK and phospho-p38, total AKT, and β-actin. (B) SKGT-4 cells were pre-incubated with LY294002, a PI3K-specific inhibitor at concentrations of 5 μM and 10 μM for 30 min before stimulating with GCDC and TCA at 200 μM for 16–24 h. Results are based on three separate experiments. (C) SKGT-4 cells were cotransfected with 1 μg of human MUC5AC promoter and 1 μg of dominant AKT (AAA) plus 0.2 mg of pSV-β-gal, and subsequently challenged with 200 μM GCDC and TCA. Luciferase reporter activities were measured after 16 h. *p<0.001.

Activation of AP-1 is Required for MUC5AC Induction by Conjugated Bile Acids

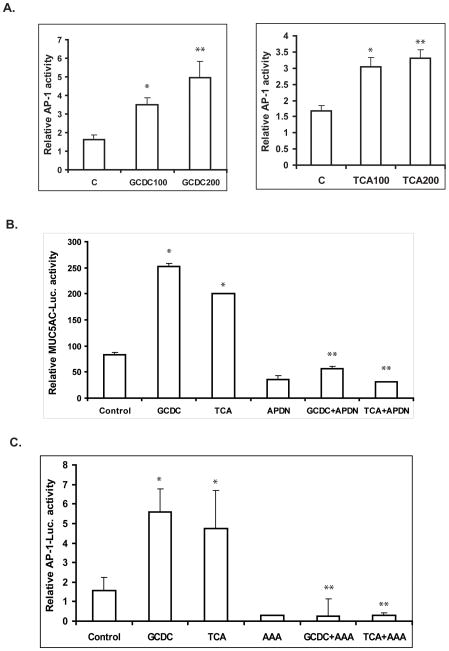

Bile acids have been reported to activate AP-1 and increase its DNA-binding activity, and the MUC5AC proximal promoter contains multiple AP-1 binding sites 29. We and others have also reported that AP-1 is required for the induction of MUC2 expression by bile acids in colon cancer cells and the induction of MUC5AC expression by tobacco smoke in lung cells30, 31. We therefore postulated that AP-1 plays a role in the induction of MUC5AC expression by conjugated bile acids. To assess this possibility, we examined AP-1 luciferase activity in SKGT-4 cells after treatment with the conjugated bile acids GCDC and TCA. Conjugated bile acids GCDC and TCA caused a dose-dependent increase in AP-1 activity, which coincided with the induction of MUC5AC (Figure 5A). In order to confirm the role of AP-1 in the regulation of MUC5AC expression by bile acids, we co-transfected a MUC5AC promoter construct (−3.7kb), which contains two AP-1 sites, with a CMV-driven dominant-negative AP-1 vector (pCMV-TAM67) into SKGT-4 cells and then treated cells with GCDC and TCA for an additional 16 hours. Dominant-negative AP-1 blocked the induction of MUC5AC transcription induced by GCDC and TCA and also decreased the basal transcriptional activity of MUC5AC (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. AP-1 mediates MUC5AC induction by conjugated bile acids GCDC and TCA.

(A) SKGT-4 cells were cotransfected with 1 μg of human AP-1 promoter plus 0.2 mg of pSV-β-gal, and treated with 100–200 μM of GCDC and TCA for 16–24 h, Luciferase reporter activities were measured and reported as described in Materials and Methods. *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

(B) SKGT-4 cells were cotransfected with 1 μg DN AP-1 (TAM67) or vector control plus 1 μg of human MUC5AC promoter + 0.2 mg of pSV-βgal, and stimulated with 200 μM GCDC and TCA for an additional 16 hours. Luciferase reporter activities were measured and reported as described in Materials and Methods. Values represent the mean and standard deviation of triplicate experiments. * p<0.05 GCDC or TCA vs control; ** p<0.005 GCDC+APDN vs GCDC or TCA+APDN vs TCA.

(C). SKGT-4 cells were cotransfected with 1 μg AP-1 promoter luciferase and 1 μg DN AKT (AAA) plus 0.2 μg of pSV-βgal, and stimulated with 200 μM GCDC and TCA for additional 16 hours. Values represent the mean and standard deviation of triplicate experiments. * p<0.01, GCDC or TCA vs control; ** p<0.001 GCDC+AAA vs GCDC or TCA+AAA vs TCA.

In order to further investigate whether AP-1 is a downstream transcription factor of PI3K/AKT responsible for the regulation of MUC5AC by conjugated bile acids, we co-transfected an AP-1-luciferase construct with a CMV-driven AKT dominant-negative construct (AKT AAA) into SKGT-4 cells. Cells were then treated with 200 μM GCDC and TCA for an additional 16 hours. The dominant-negative AKT mutant vector completely blocked the AP-1 activity induced by GCDC and TCA and also decreased the basal level of AP-1 transcriptional activity (Fig. 5C). These results demonstrate that AP-1, downstream of PI3K/AKT, is necessary for the induction of MUC5AC expression by the conjugated bile acids GCDC and TCA.

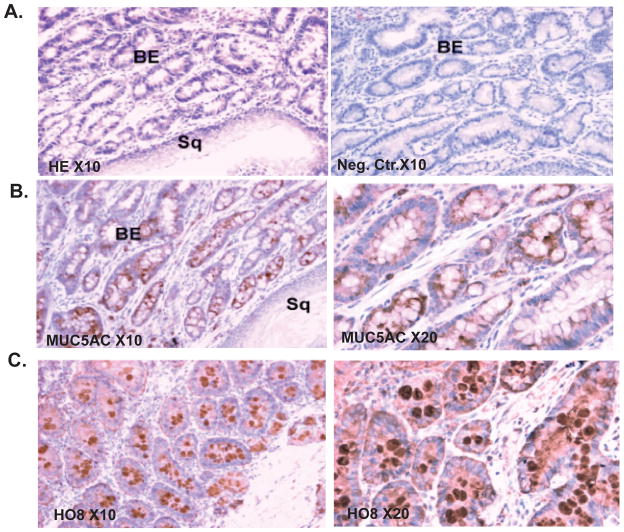

Expression of MUC5AC Mucin in Barrett’s Esophagus of Duodenoesophageal Reflux Rat Model

Barrett’s esophagus is an acquired condition that results from chronic gastroesophageal reflux. It is characterized by the replacement of the normal squamous epithelium of the lower esophagus by columnar epithelium, and the ectopic expression of the gastric mucin MUC5AC or the intestinal mucin MUC2. In a rat model in which duodenoesophageal reflux induced by the Levrat’s esophajejunostomy technique, Barrett’s esophagus occurs over time in most rats 11. MUC5AC apomucin was abundantly expressed in the cytoplasm and membranes of the epithelial cells in the Barrett’s mucosa of these rats, but not in the squamous mucosa of the lower end of the resected esophagus (Figure 6B). Abundant mature MUC5AC mucin was also detected in the lumina of glands using the MUC5AC HO8 antibody against mature MUC5AC mucin,.(Fig. 6C)

Figure 6. Expression of MUC5AC mucin in esophageal tissues from a rat model of Barrett’s esophagus.

(A) Hematoxylin-eosin staining demonstrating Barrett’s type epithelium (left panel). Negative control (right panel) (10X magnification). (B). Immunohistochemical staining for MUC5AC apomucin was performed as described in Material and Methods (10X magnification left panel, 20X magnification right panel). (C). Immunohistochemical staining for mature glycosylated MUC5AC mucin using HO8 polycolonal antibody (10X magnification left panel, 20X magnification right panel).

Discussion

Barrett’s esophagus is defined as a specialized columnar mucosa that replaces the squamous epithelium of the esophageal mucosa in response to gastroesophageal reflux. Ectopic expression of gastric and intestinal mucin genes in Barrett’s esophagus has been reported in several studies13, 15, 16, 32. However, there is little known of the risk factors and molecular mechanisms responsible for MUC5AC expression in Barrett’s esophagus and EA. We present evidence that conjugated bile acids in bile refluxate induce MUC5AC expression in the esophageal epithelium, and that this involves activation of the PI3K/AKT/AP-1 pathway. MUC5AC mucin is also abundantly expressed in Barrett’s esophagus induced in a rat model of duodenoesophageal reflux. These data demonstrate that bile reflux contributes to the development of the Barrett’s phenotype, including the ectopic expression of MUC5AC in the esophagus.

We systematically examined the pattern of expression of MUC5AC mucin in a large number of paired human tissues including paired samples of normal esophagus, Barrett’s esophagus, and adenocarcinoma. In support of previous studies 13–16, we found that MUC5AC was absent from normal squamous epithelium but present in 100% of Barrett’s specimens, with strong reactivity; in addition, it was present in 61.5% of human EA tissues, but in these tissues expression was reduced compared to paired Barett’s mucosa, and reactivity ranged from faint to medium in intensity.

Epidemiological evidence strongly suggests that bile reflux is a risk factor for the development of both Barrett’s esophagus and EA. 7, 35 In a study from our laboratory, it was found that unconjugated bile acids induce MUC2 expression in colon cancer cells4, 30. Mariette et al.4 demonstrated the transcriptional regulation of MUC4 by bile acids in esophageal cancer cells. In the present study we have demonstrated that the conjugated bile acids GCDC, TCA, GCA, and TDC, which are major components of bile refluxate in the esophagus, are strong inducers of MUC5AC apomucin expression in the esophagus, and that this regulation occurs at the transcriptional level. Further, MUC5AC apomucin and mature MUC5 mucin is expressed in the Barrett’s mucosa in a rodent model in which the esophagus is chronically exposed to duodenoesophageal reflux.

It has been demonstrated that MUC5AC expression is induced by various inflammatatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1, IL-4, IL-9, TNF-α) and cigarette smoke and by Haemophilus influenzae infection in human airway epithelial cells36–40. Song et al41 demonstrated that the MUC5AC expression induced by IL-1 and TNF-α involves ERK/P38–CREB, while Gensch E et al 31 reported that the MUC5AC expression induced by tobacco smoke requires JNK and AP-1. The transcriptional activation of the murine MUC5AC mucin gene by TGF-B/smad4 is potentiated by SP-142. The current study is the first to address the mechanisms of regulation of MUC5AC mucin by bile reflux in the esophagus. By using phospho-specific antibodies, a genetic mutant construct, and specific pharmacological inhibitors, we identified for the first time that conjugated bile acids mediate the up-regulation of MUC5AC mucin mainly by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway, a finding analogous to that of Mariette et al regarding the induction of MUC4 production by bile acids.

In order to determine the transcription factors downstream of PI3K/AKT that may be responsible for mediating the induction of MUC5AC by conjugated bile acids, we focused on AP-1. AP-1 is an important transcription factor that mediates the expression of multiple genes important in biological process, including cell growth, apoptosis, and transformation 43–45. AP-1 acts through binding to the consensus sequence [TGA(C/G)TCA] and the MUC5AC proximal promoter harbors multiple potential AP-1 sites29, 31. Our data indicate that the AP-1 transcriptional activity is induced by conjugated bile acids, and coincides with MUC5AC induction. Inhibition of AP-1 through the co-transfection of a dominant-negative AP-1 construct abolished MUC5AC transcriptional activity and its induction. Furthermore, a dominant-negative AKT construct not only blocked MUC5AC activity but also AP-1 activity and its induction by conjugated bile acids. This further suggests that the MUC5AC induction by conjugated bile acids involves both PI3K/AKT and AP-1, although other transcription factors such as NF-kB and Hath-1 could also be involved in MUC5AC up-regulation 46, 47. Additional studies are needed to further delineate the precise mechanisms by which conjugated bile acids induce MUC5AC in the esophagus, and other pathways which may be involved.

While the present study documents the role of conjugated bile acids in the induction of MUC5AC in the esophageal epithelium, it does not examine the possible functional role of this mucin in the transition from normal epithelium to Barrett’s metaplasia to carcinoma. The effects of combined bile and acid reflux on mucin expression in the esophagus also merits further study. In addition, the origen of the cell type expressing MUC5AC needs to be further delineated. The expression of MUC5AC in “multilayered epithelium (MLE)” 48 in which some cells have mucinous and/or columnar features has yet to be examined.

In conclusion, we report here that conjugated bile acids in the duodeno-gastroesophageal refluxate are potent inducers of MUC5AC expression in the esophagus, and that this involves activation of the PI3K/AKT/AP-1 pathway. Alterations in mucin expression are associated with carcinogenesis in various organs of the gastrointestinal tract 14, and additional studies are needed to investigate the pathological significance of MUC5AC ectopic expression in Barrett’s esophagus and its relation to the progression to EA. A more detailed understanding of the precise mechanism by which bile acids induce MUC5AC expression and its pathological significance in Barrett’s esophagus and EA may facilitate the development of chemopreventive strategies aimed at diminishing the risk of EA.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute grant RO1CA69480 (RSB) and the NIDDK sponsored Texas Gulf Coast Digestive Disease Center (SS).

Abbreviations used in this paper

- CD

chenodeoxycholic acid

- DC

deoxycholic acid

- GCA

glycocholic acid

- TCA

taurocholic acid

- TDC

taurodeoxycholic acid

- GCDC

glycochenodeoxycholic acid

- TCDC

taurochenodeoxycholic acid

- EA

esophageal adenocarcinoma

- AP-1

activator protein-1

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

References

- 1.Shaheen NJ. Advances in Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1554–66. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vakil N, Affi A. Esophageal cancer. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2002;18:486–9. doi: 10.1097/00001574-200207000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown LM, Devesa SS, Chow WH. Incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus among white Americans by sex, stage, and age. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1184–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mariette C, Perrais M, Leteurtre E, Jonckheere N, Hemon B, Pigny P, Batra S, Aubert JP, Triboulet JP, Van Seuningen I. Transcriptional regulation of human mucin MUC4 by bile acids in oesophageal cancer cells is promoter-dependent and involves activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signalling pathway. Biochem J. 2004;377:701–8. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bresalier RS. Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60:221–231. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.59.061206.112706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menges M, Muller M, Zeitz M. Increased acid and bile reflux in Barrett’s esophagus compared to reflux esophagitis, and effect of proton pump inhibitor therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:331–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stein HJ, Kauer WK, Feussner H, Siewert JR. Bile reflux in benign and malignant Barrett’s esophagus: effect of medical acid suppression and nissen fundoplication. J Gastrointest Surg. 1998;2:333–41. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(98)80072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeMeester TR. Antireflux surgery in the management of Barrett’s esophagus. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:124–8. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(00)80046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer W, Vollmar F, Bar W. Barrett-esophagus following total gastrectomy. A contribution to it’s pathogenesis. Endoscopy. 1979;11:121–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1098335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishijima K, Miwa K, Miyashita T, Kinami S, Ninomiya I, Fushida S, Fujimura T, Hattori T. Impact of the biliary diversion procedure on carcinogenesis in Barrett’s esophagus surgically induced by duodenoesophageal reflux in rats. Ann Surg. 2004;240:57–67. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000130850.31178.8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fein M, Peters JH, Chandrasoma P, Ireland AP, Oberg S, Ritter MP, Bremner CG, Hagen JA, DeMeester TR. Duodenoesophageal reflux induces esophageal adenocarcinoma without exogenous carcinogen. J Gastrointest Surg. 1998;2:260–8. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(98)80021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aishima S, Kuroda Y, Nishihara Y, Taguchi K, Taketomi A, Maehara Y, Tsuneyoshi M. Gastric mucin phenotype defines tumour progression and prognosis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: gastric foveolar type is associated with aggressive tumour behaviour. Histopathology. 2006;49:35–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arul GS, Moorghen M, Myerscough N, Alderson DA, Spicer RD, Corfield AP. Mucin gene expression in Barrett’s oesophagus: an in situ hybridisation and immunohistochemical study. Gut. 2000;47:753–61. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.6.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byrd JC, Bresalier RS. Mucins and mucin binding proteins in colorectal cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2004;23:77–99. doi: 10.1023/a:1025815113599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warson C, Van De Bovenkamp JH, Korteland-Van Male AM, Buller HA, Einerhand AW, Ectors NL, Dekker J. Barrett’s esophagus is characterized by expression of gastric-type mucins (MUC5AC, MUC6) and TFF peptides (TFF1 and TFF2), but the risk of carcinoma development may be indicated by the intestinal-type mucin, MUC2. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:660–8. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.124907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flucke U, Steinborn E, Dries V, Monig SP, Schneider PM, Thiele J, Holscher AH, Dienes HP, Baldus SE. Immunoreactivity of cytokeratins (CK7, CK20) and mucin peptide core antigens (MUC1, MUC2, MUC5AC) in adenocarcinomas, normal and metaplastic tissues of the distal oesophagus, oesophago-gastric junction and proximal stomach. Histopathology. 2003;43:127–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2003.01680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van de Bovenkamp JH, Mahdavi J, Korteland-Van Male AM, Buller HA, Einerhand AW, Boren T, Dekker J. The MUC5AC glycoprotein is the primary receptor for Helicobacter pylori in the human stomach. Helicobacter. 2003;8:521–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2003.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soldes OS, Kuick RD, Thompson IA, 2nd, Hughes SJ, Orringer MB, Iannettoni MD, Hanash SM, Beer DG. Differential expression of Hsp27 in normal oesophagus, Barrett’s metaplasia and oesophageal adenocarcinomas. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:595–603. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gray T, Nettesheim P, Basbaum C, Koo J. Regulation of mucin gene expression in human tracheobronchial epithelial cells by thyroid hormone. Biochem J. 2001;353:727–34. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3530727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown PH, Chen TK, Birrer MJ. Mechanism of action of a dominant-negative mutant of c-Jun. Oncogene. 1994;9:791–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee HY, Dawson MI, Claret FX, Chen JD, Walsh GL, Hong WK, Kurie JM. Evidence of a retinoid signaling alteration involving the activator protein 1 complex in tumorigenic human bronchial epithelial cells and non-small cell lung cancer cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1997;8:283–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shishodia S, Koul D, Aggarwal BB. Cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitor celecoxib abrogates TNF-induced NF-kappa B activation through inhibition of activation of I kappa B alpha kinase and Akt in human non-small cell lung carcinoma: correlation with suppression of COX-2 synthesis. J Immunol. 2004;173:2011–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le XF, Lammayot A, Gold D, Lu Y, Mao W, Chang T, Patel A, Mills GB, Bast RC., Jr Genes affecting the cell cycle, growth, maintenance, and drug sensitivity are preferentially regulated by anti-HER2 antibody through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-AKT signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2092–104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403080200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buttar NS, Wang KK, Leontovich O, Westcott JY, Pacifico RJ, Anderson MA, Krishnadath KK, Lutzke LS, Burgart LJ. Chemoprevention of esophageal adenocarcinoma by COX-2 inhibitors in an animal model of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1101–12. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsu SM, Raine L, Fanger H. Use of avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) in immunoperoxidase techniques: a comparison between ABC and unlabeled antibody (PAP) procedures. J Histochem Cytochem. 1981;29:577–80. doi: 10.1177/29.4.6166661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holt PR, Bresalier RS, Ma CK, Liu KF, Lipkin M, Byrd JC, Yang K. Calcium plus vitamin D alters preneoplastic features of colorectal adenomas and rectal mucosa. Cancer. 2006;106:287–96. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaiswal K, Tello V, Lopez-Guzman C, Nwariaku F, Anthony T, Sarosi GA., Jr Bile salt exposure causes phosphatidyl-inositol-3-kinase-mediated proliferation in a Barrett’s adenocarcinoma cell line. Surgery. 2004;136:160–8. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kauer WK, Peters JH, DeMeester TR, Feussner H, Ireland AP, Stein HJ, Siewert RJ. Composition and concentration of bile acid reflux into the esophagus of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surgery. 1997;122:874–81. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(97)90327-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kato S, Hokari R, Crawley S, Gum J, Ahn DH, Kim JW, Kwon SW, Miura S, Basbaum CB, Kim YS. MUC5AC mucin gene regulation in pancreatic cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2006;29:33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song S, Byrd JC, Koo JS, Bresalier RS. Bile acids induce MUC2 overexpression in human colon carcinoma cells. Cancer. 2005;103:1606–14. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gensch E, Gallup M, Sucher A, Li D, Gebremichael A, Lemjabbar H, Mengistab A, Dasari V, Hotchkiss J, Harkema J, Basbaum C. Tobacco smoke control of mucin production in lung cells requires oxygen radicals AP-1 and JNK. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:39085–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406866200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glickman JN, Blount PL, Sanchez CA, Cowan D, Wongsurawat VJ, Reid BJ, Odze RD. Mucin core polypeptide expression in the progression of neoplasia in the esophagus. Human Pathol. 2006;37:1304–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaves P, Cruz C, Dias Pereira A, Suspiro A, de Almeida JC, Leitao CN, Soares J. Gastric and intestinal differentiation in Barrett’s metaplasia and associated adenocarcinoma. Dis Esophagus. 2005;18:383–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2005.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim GE, Bae HI, Park HU, Kuan SF, Crawley SC, Ho JJ, Kim YS. Aberrant expression of MUC5AC and MUC6 gastric mucins and sialyl Tn antigen in intraepithelial neoplasms of the pancreas. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1052–60. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stipa F, Stein HJ, Feussner H, Kraemer S, Siewert JR. Assessment of non-acid esophageal reflux: comparison between long-term reflux aspiration test and fiberoptic bilirubin monitoring. Dis Esophagus. 1997;10:24–8. doi: 10.1093/dote/10.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borchers MT, Carty MP, Leikauf GD. Regulation of human airway mucins by acrolein and inflammatory mediators. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:L549–55. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.4.L549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Young Kim J, Kim CH, Kim KS, Choi YS, Lee JG, Yoon JH. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase is involved in tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced MUC5AC gene expression in cultured human nasal polyp epithelial cells. Acta Otolaryngol. 2004;124:953–7. doi: 10.1080/00016480310017054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shao MX, Ueki IF, Nadel JA. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-converting enzyme mediates MUC5AC mucin expression in cultured human airway epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11618–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1534804100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shao MX, Nakanaga T, Nadel JA. Cigarette smoke induces MUC5AC mucin overproduction via tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme in human airway epithelial (NCI-H292) cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:L420–7. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00019.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baginski TK, Dabbagh K, Satjawatcharaphong C, Swinney DC. Cigarette smoke synergistically enhances respiratory mucin induction by proinflammatory stimuli. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35:165–74. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0259OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song KS, Lee WJ, Chung KC, Koo JS, Yang EJ, Choi JY, Yoon JH. Interleukin-1 beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha induce MUC5AC overexpression through a mechanism involving ERK/p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases-MSK1-CREB activation in human airway epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23243–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300096200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jonckheere N, Van Der Sluis M, Velghe A, Buisine MP, Sutmuller M, Ducourouble MP, Pigny P, Buller HA, Aubert JP, Einerhand AW, Van Seuningen I. Transcriptional activation of the murine Muc5ac mucin gene in epithelial cancer cells by TGF-beta/Smad4 signalling pathway is potentiated by Sp1. Biochem J. 2004;377:797–808. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shaulian E, Karin M. AP-1 in cell proliferation and survival. Oncogene. 2001;20:2390–400. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shaulian E, Karin M. AP-1 as a regulator of cell life and death. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:E131–6. doi: 10.1038/ncb0502-e131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karin M, Shaulian E. AP-1: linking hydrogen peroxide and oxidative stress to the control of cell proliferation and death. IUBMB Life. 2001;52:17–24. doi: 10.1080/15216540252774711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li D, Gallup M, Fan N, Szymkowski DE, Basbaum CB. Cloning of the amino-terminal and 5′-flanking region of the human MUC5AC mucin gene and transcriptional up-regulation by bacterial exoproducts. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6812–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sekine A, Akiyama Y, Yanagihara K, Yuasa Y. Hath1 up-regulates gastric mucin gene expression in gastric cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;344:1166–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Upton MP, Nishioka NS, Ransil B, Rosenberg S, Puricelli WP, Zwas FR, Shields HM. Multilayered epithelium may be found in patients with Barrett’s epithelium and dysplasia or adenocarcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:1783–1790. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]