Abstract

Objectives

Dosage of methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) is an important factor influencing retention in methadone treatment. MMT clients in China received lower dosages of methadone compared with those provided in other countries. The objective of this study is to elucidate the reason for the low methadone dosage prescribed in MMT clinics in China.

Methods

Twenty-eight service providers were recruited from the MMT clinics in Zhejiang and Jiangxi Provinces, China. Qualitative in-depth interviews were conducted to ascertain the procedure for prescribing methadone in the MMT clinics.

Results

The average dosage prescribed in the 28 clinics was 35 mg per person per day. Four major themes resulting in low dosage of methadone were identified: (1) the service providers fear the liability resulting from large doses of methadone in combination with other substances which might result in overdose fatalities, (2) lack of understanding of harm reduction which resulted in low acceptance of the long term maintenance treatment approach, (3) break-down in communication between clients and service providers about dosage adjustment, and (4) dosage reduction is perceived by most service providers as an effective way to treat the side-effects associated with MMT.

Conclusions

The findings of the study highlighted the necessity to formulate clear guidelines concerning individualized dosage management and to improve training among service providers’ in MMT clinics in China.

Keywords: Methadone maintenance therapy, China, opioid use, dosage, qualitative study

1. Introduction

Methadone is a long-acting, orally administered synthesized analgesic drug used to treat cancer pain (Joseph et al., 2000). Since Dole and Nyswander proposed methadone as substitution treatment for heroin addiction in 1965, methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) has become a first-line treatment for opioid addiction. Methadone can be taken once a day to reduce craving for heroin and to suppress opioid withdrawal, thereby freeing the patient from the daily cycle of seeking out, buying, and using heroin (Ward et al., 1999; Joseph et al., 2000). Substantial evidence has shown that MMT is effective in reducing the morbidity and criminality associated with heroin abuse (Gossp et al., 2005; Flynn et al., 2003; Loughlin et al., 2004). Studies worldwide have also confirmed that MMT plays a crucial role in prevention of the transmission of blood borne diseases (Metzger et al., 1993; Thiede et al., 2000).

Many studies have found that methadone dose is an important factor influencing retention in methadone treatment. Some systematic reviews have reported higher rates of dropout among those who received lower doses of methadone (Amato et al., 2005; Bao et al., 2009; Faggiano et al., 2003). Several randomized, controlled trials have also supported the findings by showing that higher doses of methadone were associated with significantly longer retention (Ling et al., 1996; Preston et al., 2000; Strain et al., 1999). The U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Conference guidelines for methadone substitution therapy thus recommend that a dose of 60 mg is the minimum effective maintenance dose for most patients (NIH Consensus Conference, 1998). In most of countries, methadone is prescribed in dosages of 60–80 mg per day (Kimber et al., 2005).

MMT was initiated in China in 2004 (Pang et al., 2007). With the success of the pilot clinics, the MMT program has been rapidly scaled up in China. As of December 2009, 680 MMT clinics had been established nationwide in 27 provinces cumulatively serving more than 240,000 clients. The clinics are under the leadership of a national working group, consisting of members of the Ministries of Health, Public Security, and the State Food and Drug Administration. The national Working Group has overall responsibility for administration, planning, supervision and evaluation. Corresponding working groups have been organized at the provincial and county levels to take on these duties locally. MMT clinics are non-profit medical facilities assigned by local public security and public health departments to be established and operated by local Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), hospitals, or voluntary detoxification centers in areas with a concentration of drug users (Yin et al., 2010). Typically, each MMT clinic is required to have eight to ten staff members. Doctors are primarily responsible for prescribing methadone, providing physical examination, and psychological counselling, and they are required to be certified physicians authorized to prescribe analgesic and psychotropic drugs. A nurse is responsible for dispensing methadone to the clients and observing them taking the methadone. Other clinic staff members are responsible for data entry, management, report and other logistical issue. One or two security personnel are required for each of the MMT clinic (Ministry of Health, Ministry of Public Security of China, and SFDA, 2006).

MMT clients in China receive lower dosages of methadone compared with patients treated in other countries (Sullivan and Wu, 2007). The average daily dosage of methadone given to Chinese clients in eight pilot MMT clinics was 44.9±21.9 mg (Pang et al., 2007). A prospective cohort study among 1003 clients has reported that the average methadone dose for all participants was 38.0 mg/day, and 79.4% of participants received lower than 50 mg/day (Liu et al., 2009). Lower dosages compared with what has been suggested optimal in other counties may contribute to the high drop-out rate in China (Pang et al., 2007; Sullivan and Wu, 2007). This study used qualitative methods to elucidate the reason for the low methadone dosages prescribed by service providers working in MMT clinics in China. The findings from this study would shed lights on the formulation of strategies to improve MMT program in China.

2. Methods

2.1. Study sites

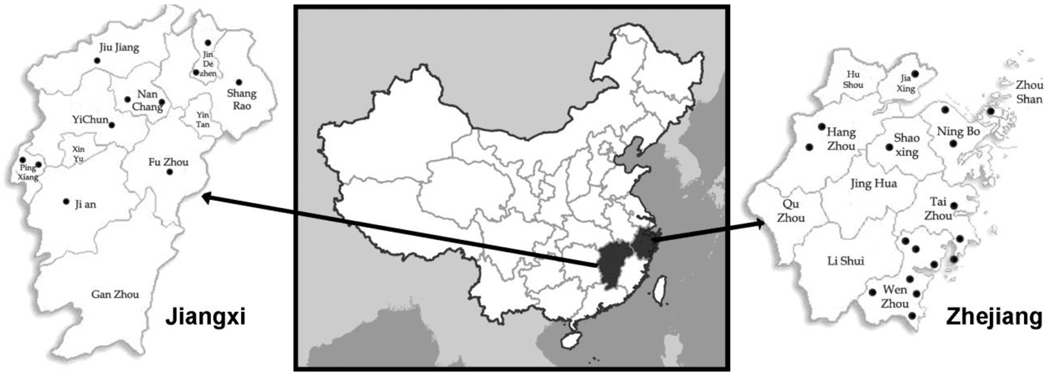

The study was conducted in Zhejiang and Jiangxi Provinces, China (Figure 1). Zhejiang Province is located on China's south-eastern coast, and covers a total land area of 101,800 sq km. It had a population of 51.8 million at the end of 2009. Zhejiang is a relatively wealthy coastal province with advanced educational and health care systems. The gross domestic product (GDP) was 2.28 trillion yuan in 2009 (The people’s government of Zhejiang Province, 2010). Jiangxi Province is one of China's inland provinces. It is located in the south-eastern part of the country, covering a total area of 166,900 sq km. Jiangxi is a less developed inland province compared with Zhejiang. The GDP for 2009 in Jiangxi was 759 billion yuan (The people’s government of Jiangxi province, 2010). More than 99% of the people of Jiangxi and Zhejiang are of the Han Chinese Majority (The people’s government of Jiangxi province, 2010; The people’s government of Zhejiang Province, 2010).

Figure 1.

Map of the study sites

At the time of the study, Zhejiang province had 17 methadone maintenance clinics cumulatively treating 5,060 clients, and Jiangxi had 11 methadone maintenance clinics cumulatively serving 2,666 clients. The overall retention rate of the 28 clinics was 51.4% at the time of the study. Slightly less than half (46.4%) of the clinics were affiliated with the local CDC, while the others were affiliated with either hospitals or voluntary detoxification centres. Each clinic had an average of 6.4 service providers, ranging from 5–15. In another study using a random sample of clients from the clinics, the author reported that more than 80% of the clients from the 28 clinics were male, about half were 30–39 years of age, and 30% were unemployed. A large proportion (about 70%) were injecting drug users, and more than half had a drug use history of more than 10 years. Participants spent on average 568 yuan (83.5 USD) per day on drugs before they started MMT (Lin et al., 2010a).

2.2. Study participants

Between March and September, 2008, one service provider from each of the 28 MMT study clinics in Zhejiang and Jiangxi was invited to participate in a face-to-face in-depth interview. In order to include service providers who were relatively better informed, we obtained recommendations for interview participants from the head of each MMT clinic. Study investigators approached the recommended individuals and invited them to participate in our study with a refusal rate of 3%. The service provider had to be at least 18 years old and to have been working in the MMT clinic for more than three months to participate. We selected service providers of different ages, genders, and levels of education and professional training in order to obtain comprehensive information. Of the 28 service providers interviewed, 16 (57.1%) were male, with age ranging from 26 to 65 years. Twelve (42.9%) of the participants were doctors, five (17.9%) were nurses, and the remainder (11, 39.3%) were clinic directors. At the time of the survey, all of them had been working in the clinics for more than a year, and 6 (21.4%) for more than two years. Half (14) of the sample had a five-year or higher medical degree (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the 28 service providers who participated in qualitative in-depth interviews

| Number | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Province | ||

| Zhejiang | 17 | 60.7% |

| Jiangxi | 11 | 39.3% |

| Age | ||

| 20–29 years | 4 | 14.3% |

| 30–39 years | 7 | 25.0% |

| 40–49 years | 8 | 28.6% |

| 50 and above | 9 | 32.1% |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 16 | 57.1% |

| Female | 12 | 42.9% |

| Education level | ||

| Senior high | 6 | 20.0% |

| Associate college | 8 | 43.3% |

| College and above | 14 | 36.7% |

| Profession | ||

| Clinic administrator | 11 | 39.3% |

| Doctor | 12 | 42.9% |

| Nurse | 5 | 17.9% |

| Length of service (months) | ||

| 12–18 months | 11 | 39.3% |

| 19–24 months | 11 | 39.3% |

| 25 months or more | 6 | 21.4% |

2.3. Data collection

The respondents were informed of the study purpose, procedures, and potential benefits and risks of the study before the in-depth interview. Informed consent procedures were used, and participation was voluntary. All participants received 40 Yuan (U.S. $5.88) for their participation. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) of both the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), and the China CDC.

The in-depth interviews were conducted by experienced investigators for approximately 60–120 minutes in private rooms. Interviews were semi-structured according to specific guidelines, and included a set of open-ended probes to be used when necessary. All interviews were digitally audio-recorded for analysis and quality control. There were no personal identifiers linked to the recorded interviews. During the interview the respondents were asked about their socio-demographics, general working procedure in the MMT clinics, the training received, the procedure for methadone prescription at their daily work, administration of methadone dosage and the difficulties of increasing dosage.

2.4. Data analysis

The digitally recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim in Chinese. Cross–checking and confirmations of the transcriptions were done to assure the quality of work. The data were coded and analyzed using ATLAS.ti (Muhr, 1997), a qualitative data analysis software package. A grounded theory approach was used to analyse the data (Glaser and Strauss, 1967). A first draft of the code list was developed by the research team based on the interview guidelines. The code list was then revised throughout the analysis process based on the actual content of interview transcripts. Following a variety of revisions, a final code system was established, with a total of 56 codes and 10 code “families” (grouping of codes with the same theme). Analyses were conducted by identifying the themes occurring most frequently, and putting them in the context of other information conveyed by the participants. In order to reach better inter-coder reliability, the first three transcripts were coded by the team together and the definitions of code categories were then fine-tuned (Sandelowski, 1986). All transcriptions, coding, and analyses were completed in Chinese, and the results were later translated into English using the “forward-backward” translation procedure (Brislin, 1970).

3. Results

At entry into treatment, the doctors initially prescribed a medication dosage on the basis of client report of drug usage that minimizes sedation and other undesirable side-effects, usually no more than 50 mg. Then the doctors started assessing the safety and adequacy of each dose from the second day of treatment and adjusted the methadone dosage according to the client’s self-reported withdrawal symptoms, side effects, concurrent drug use and urine morphine test result. The average dosage prescribed in the 28 clinics was 35 mg per person per day. After analyzing the transcripts, four major themes resulting in low dosage of methadone were identified: (1) fear of liability, (2) ambiguous treatment goals, (3) poor provider-client communication, and (4) side effects. Results for each of these themes are described in detail below.

3.1. Fear of Liability

Although there were national guidelines on appropriate methadone doses to administer to MMT clients, service providers typically feared malpractice liability in spite of the guidelines. Methadone overdose, although never happened in the participating clinics before, has been a serious concern among service providers. Many respondents said that they felt uncomfortable prescribing high dose of methadone, given the fact that a proportion of the clients were concurrently using heroin. It was perceived by the service providers that large doses of methadone in combination with other substances would result in toxic reactions and overdose fatalities.

We don’t want to raise the dosage too much, and we want to be conservative, really conservative. You should be aware that some clients not only use methadone here, they also inject drugs, and it is unlikely that they would tell us the truth. We could only adjust the dose according to what they told use, and nothing else. If they told us to increase the dose, we will do so. (Female, 26 years old, college graduated, doctor)

We dare not to prescribe them high dosage. Some of them often concurrently use heroin, and the drug-interaction will just poison them? We don’t want that to happen. (Male, 54 years old, vocational secondary school graduated, doctor)

3.2. Ambiguous treatment goals

Most service providers in our study did not have a clear understanding of the meaning of harm reduction which had resulted in relatively low acceptance of the long term maintenance treatment approach. The service providers were also aware of the fact that MMT requires its users to attend clinics on a daily basis, which poses logistical difficulties for many users (such as long daily commute times, conflict with working and family schedule, etc.). The respondents consistently reported that the overwhelming majority of their clients did not want to stay in the life-long maintenance program because of these inconveniences. Thus, many of the clients who voluntarily attempted to reduce their methadone dosage to zero mg, that was, “taper” from methadone.

After a period of time, the clients will absolutely raise this issue (of reducing dose). The clients always have a few misunderstandings, especially at the entry of the treatment, if we did not give him very clear explanation. They think it is a detoxification treatment with a tapering dosage. We have made it clear that the drug using thing is a chronic disease, like hypertension and diabetes, which needs lifetime treatment, but some clients just would not accept it, because they need to find a job, and financial difficulty is also a problem. (Male, 40 years old, college graduated, doctor)

The old idea of detoxification is difficult to change. Many of our clients have the experience of detoxification treatment, which decrease the dosage by 20% per day. The clients are quite accustomed to this old tradition, so even we kept telling them over and over again, the maintenance treatment is different, you will have to stick to it for a long time, you can’t just quit in 15 days something, they still don’t accept it. They told me that they understand it, but actually they do not. Or I should say they are not prepared to take it for lifetime. To be honest, it is hard for most of the people, if they had such perseverance, they would not have had to be here. (Male, 65 years old, associated college graduated, doctor)

This posed the service providers in methadone clinics a dilemma: they should either encourage clients to remain on methadone for the rest of their lives, or encourage clients to taper off methadone. Although the majority (over 80%) of the service providers perceived tapering as a risky and difficult procedure, and very few clients who had tapered successfully, there were still some service providers that encouraged the clients to taper their methadone dose in order to regain drug-free status.

We have been encouraging the patients to reduce the dosage gradually. We feel that, after more than a year of exploration, we found that this method is quite effective. If the client was on 30 mg or more for a period of time, and he or she feels okay with everything, then we encourage him to reduce the dosage by 5 mg each time. We think it is a good way to do it. (Male, 40 years old, college graduated, doctor)

Doctors advocate a tapering dosage after a certain time. We don’t think the life-time treatment will be a good idea. Some clients are good at controlling themselves. We believe that they can totally get rid of the addiction after a while. (Male, 47 years old, vocational secondary school graduated, director)

3.3. Poor provider-client communication

Despite the likelihood of beneficial effects of methadone, the relationship between service providers and clients of MMT clinics appeared to be very different from other medical care settings. Almost all of the respondents had been threatened by clients in order to get a desired methadone dosage. On the other hand, because of the heavy working load and lack of expertise, many MMT service providers did not regularly carry out counseling with their clients. The break-down in communication between clients and service providers and sporadic counseling created problems for prescribing medication. Some physicians just prescribed whatever dosage was demanded by the clients. The patients sometimes asked for a reduced dosage, if the request was not fulfilled, they just spit out the prescribed drugs which left the service providers in dilemma.

We can’t use tough words with the clients. They asked for certain dosage, you can just let them. If you raise your voice a little bit, they will beat our doctors. (Male, 56 years old, high school graduated, doctor)

One client told me that, “Dr. Wang, to tell you the truth, I didn’t take the methadone you prescribed me, I spitted it…” I was so mad to hear that, it is such a waste! You see, the pharmacists didn’t pay attention to their behaviour when they are taking the medication, and they don’t know how to discipline the clients. Those untrained doctors, they just prescribe whatever dosage demanded by the clients. The client asks for 20, they gave him 20, ask for 30, gave him 30, they are totally under the control of clients. The dosage thing is so difficult. (Female, 51 years old, associated college graduated, doctor)

We need to respect our clients. Although in principal it should be our doctors who are controlling the dosage, but if the client has certain requests, we will consider it. The client knows better about their body than we do. (Male, 47 years old, vocational secondary school graduated, director)

3.4. Side effects

The participants reported that a considerable proportion of their clients suffer from side effects including constipation, erectile dysfunction, menstrual cycle irregularities, and sleeping disorders. For some of the clients, the side effects were severe enough to interfere with their daily lives and family relationships.

Unfortunately, the majority of service providers knew few effective ways to treat these side-effects. Facing the clients’ complaints, only one or two clinics came up with positive ways to treat the clients with traditional Chinese medicines or referred them to other health care facilities. Traditional Chinese medicines provided in these clinics were mostly symptomatic treatment. For example, those who reported constipation would be given herbal laxatives. For severe and complicated side-effects, the most effective treatment side-effects acknowledged by most service providers was to lower the dosage. Consequently, the reduced methadone dose eventually did not stop the withdrawal symptom and probably contributed to relapse to heroin use and the high rates of drop-out from the clinic.

Irregular menstruation is common among female clients. They experienced menopause if we kept the dose at 50–60mg. they don’t have their period unless we lower the dosage to less than 10 mg. It is a common situation. (Male, 50 years old, vocational secondary school graduated, doctor)

Our dosage is very low, only 30mg on average. We are aware of the regulation which says it needs 50–60 mg to maintain the drug-free status, but it is hard, because the medication arouses severe gastrointestinal tract responses….A girl started the treatment about two weeks ago, she had 33mg the day before yesterday, and told me that she vomited badly, so I reduced the dosage to 30 mg but it was the same, so I reduced to it 27mg and she felt better, that was the only thing you can do (Female, 43 years old, college graduated, doctor).

We Chinese believe that “as a medicine, it is more or less toxic”. As the treatment continues, the side effects, such as constipation and erectile-dysfunction become more and more severe. The clients are still young in age, so sexuality is a very important part of their life. We really tried hard to persuade them to take more (methadone), but they are just not willing to. They believe that the less they take, the better their sexual function will be. (Male, 65 years old, associated college graduated, doctor)

4. Discussion

Because of the rapid implementation of the MMT program in China and the apparent lack of sufficient experiences, currently there is no systematic and clear guideline regarding MMT dosage adjustments in China. Researchers in other countries have recommended that methadone doses be individualized and flexible, as there is no single best dose for all patients (Leavitt et al., 2000; Trafton et al., 2006). Bao and colleagues’ 2009 study suggested that retention will be greatest when the dosing strategy is flexible and doses are relatively high (Bao et al., 2009). Dose reduction and subsequent dose adjustments have usually been required in practice (Leavitt et al., 2000; Trafton et al., 2006), so methadone prescription, a seemingly simple procedure, can be complicated and subtle. The findings of this study demonstrate the urgent need to establish a comprehensive guideline to serve as guiding principles in MMT clinic’s daily practice. Such guidelines should stipulate the dosage adjustments necessary in the presence of side effects, in detection of concurrent substance use, and in a variety of other situations.

Overdose related adverse events, although very rare, have been a concern of the service providers in their prescription. However, the service providers should be aware of the fact that a proportion of MMT clients continue to use illegal drugs on top of their medication which indicates that current prescribing practices are less than optimal, and their current level of medication is insufficient for their needs. Such a mismatch between treatment aims and outcomes mandates careful monitoring and evaluation of substitution therapy. Several algorithms for individualization of doses, such as dose adjustment based on urine toxicology and withdrawal symptoms are recommended (Johnson et al., 2000; Strain et al., 1999). In addition, training is desperately needed to help the staff feel competent to manage the potential methadone overdose problems which occur in MMT clinics.

Given the short history of MMT in China, both service providers and clients were not yet accustomed to the idea of harm reduction and still adhere to the old detoxification tradition. In addition, because of some logistic and financial barriers for maintenance treatment, there exists a subgroup of MMT clients with considerable motivation to taper off methadone (Lin et al., in press). Physician’s decisions regarding dosage adjustment in such situations are crucial for treatment success. Studies have showed that withdrawal limited to 30 days has disadvantage for many clients, as the rapid tapering of methadone would result in premature withdrawal of treatment with subsequent resumption of heroin use (Amato et al., 2005).

A considerable proportion of the MMT clients in China suffer from side effects related to maintenance treatment. Some of the side effects were severe enough to interfere with their daily lives so should not be neglected (Lin et al., in press). The MMT clients often felt ashamed to seek treatment for methadone-related symptoms in other health care settings. If these symptoms were not treated appropriately in the MMT clinics they might add to the risk of early termination of the treatment. Side effects have also been cited as barriers to treatment in the U.S. (Peterson et al, 2010). Lowering the dosage was by no means the only way to solve the problem. Effective medical management of the side-effects, including traditional Chinese medicines, is encouraged. A referral system should also be established to provide MMT clients with timely treatment of their side effects.

Professional training related to MMT has been lacking among the service providers (Lin et al., 2010b). The insufficient knowledge and skills lacking among service providers not only hinders them from prescribing appropriate treatment dosages and monitoring, but also results in inadequate communication with clients about their treatment outcome, dosage, and risk management, leading to an overall decrease in the effectiveness of clinic operations. A well-trained staff is the key for effective MMT program (Ward et al., 1999). Appropriate and ongoing training, especially in the area of motivation enhancement, psychological counselling, and behaviour intervention is urgently needed by MMT service providers. Developing methods to maintain regular counselling attendance would benefit both clients and the service providers.

There are some limitations in the study that should be noted. The data were collected from a region with moderate drug-use problems. Service providers and MMT programs in this area might differ from other parts of China. As a qualitative study, the sample was not representative of all service providers, limiting the generalizability of the results. Nonetheless, the findings of the study highlight the necessity to formulate clear guidelines for substitution treatment, especially concerning dosage management and to improve service providers’ training in China.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amato L, Davoli MA, Perucci C, Ferri M, Faggiano FP, Mattick R. An overview of systematic reviews of the effectiveness of opiate maintenance therapies: available evidence to inform clinical practice and research. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2005;28:321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Y, Liu Z, Epstein DH, Du C, Shi J, Lu L. A Meta-Analysis of Retention in Methadone Maintenance by Dose and Dosing Strategy. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35:28–33. doi: 10.1080/00952990802342899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brislin RW. Back translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 1970;1:185–216. [Google Scholar]

- Dole VP, Nyswander M. A medical treatment for diacetylmorphine (heroin) addiction: a clinical trial with methadone hydrochloride. JAMA. 1965;193:80–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.1965.03090080008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faggiano F, Vigna-Taglianti F, Versino E, Lemma P. Methadone maintenance at different dosages for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2003;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002208. CD002208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn PM, Joe GW, Broome KW, Simpson DD, Brown BS. Looking back on cocaine dependence: reasons for recovery. Am. J. Addict. 2003;12:398–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Gossp M, Trakada K, Steward D, Witton J. Reduction in criminal convictions after addiction treatment: 5-year follow-up. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RE, Chutuape MA, Strain EC, Walsh SL, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE. A comparison of levomethadyl acetate, buprenorphine, and methadone for opioid dependence. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;343:1290–1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011023431802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph H, Stancliff S, Langrod J. Methadone maintenance treatment (MMT): a review of historical and clinical issues. Mt. Sinai J. Med. 2000;67:347–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimber J, Dolan K, Wodak A. Survey of drug consumption rooms: service delivery and perceived public health and amenity impact. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2005;24:21–24. doi: 10.1080/09595230500125047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavitt SB, Shinderman M, Maxwell S, Eap CB, Paris P. When “enough” is not enough: new perspectives on optimal methadone maintenance dose. Mt. Sinai J. Med. 2000;67:404–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling W, Wesson DR, Charuvastra C, Klett CJ. A controlled trial comparing buprenorphine and methadone maintenance in opioid dependence. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1996;53:401–407. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830050035005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Wu Z, Rou K, Yin W, Wang C, Shoptaw S, Detels R. Structural-level factors affecting implementation of the methadone maintenance therapy program in China. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2010a;38:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Wu Z, Rou K, Pang L, Cao X, Shoptaw S, Detels R. Challenges in providing services in methadone maintenance therapy clinics in China: service providers' perceptions. Int. Drug Policy. 2010b;21:173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C, Wu Z, Rou K, Pang L, Yin W, Shoptaw S, Detels R. Drug users’ perceived barriers against attending methadone maintenance therapy: a qualitative study in China. Subst. Use Misuse. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.561905. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu E, Liang T, Shen L, Zhong H, Wang B, Wu Z, Detels R. Correlates of methadone client retention: a prospective cohort study in Guizhou province, China. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2009;20:304–308. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughlin AM, Schwarts R, Strathdee SA. Prevalence and correlates of HCV infections among methadone treatment attendees: implications for HCV treatment. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2004;15:93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger DS, Woody GE, McLellan AT, O’Brien CP, Druley P, Navaline H, DePhilippis D, Stolley P, Abrutyn E. Human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion among intravenous drug users in- and out-of-treatment: an 18-month prospective follow-up. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 1993;6:1049–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health of China (MOH), Ministry of Public Security of China, and State Food and Drug Administration (SFDA) [Accessed on December 28, 2010];Work Plan of Community Maintenance Treatment for Opioid Addicts. 2006 www.chinaaids.cn/worknet/download/2005/0308.doc.

- Muhr T. Atlas. TI [Computer software] Berlin: Scientific Software Development; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- NIH Consensus Conference. Effective medical treatment of opiate addiction. JAMA. 1998;280:1936–1943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang L, Hao Y, Mi GD, Wang CH, Luo W, Rou KM, Li J, Wu Z. Effectiveness of first eight methadone maintenance treatment clinics in China. AIDS. 2007;21:S103–S107. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304704.71917.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JA, Schwartz RP, Mitchell SG, Reisinger HS, Kelly SM, O’Grady KE, Brown BS, Agar MH. Why don’t out-of-treatment individuals enter methadone treatment programmes? Int. J. Drug Policy. 2010;21:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston KL, Umbricht A, Epstein DH. Methadone dose increase and abstinence reinforcement for treatment of continued heroin use during methadone maintenance. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2000;57:395–404. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. The problem of rigor in qualitative research. ANS. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 1986;8:27–37. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198604000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strain EC, Bigelow GE, Liebson IA, Stitzer ML. Moderate- vs. Highdose methadone in the treatment of opioid dependence: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1999;281:1000–1005. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.11.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan GS, Wu Z. Rapid scale up of harm reduction in China. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2007;18:118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The people’s government of Jiangxi Province. [Accessed on December 28, 2010];Jiangxi’s GDP Exceeds RMB700b in 2009. 2010 http://english.jiangxi.gov.cn/ForInvestment/InvestmentEnvironment/201003/t20100305_202175.htm.

- The people’s government of Zhejiang Province. [Accessed on December 28, 2010];Statistical Bulletin of national economic and social development in Zhejiang Province 2009. 2010 http://www.zhejiang.gov.cn/gb/zjnew/node3/node22/node168/node370/node381/userobject9ai113454.html.

- Thiede H, Hagan H, Murrill CS. Methadone treatment and HIV and hepatitis B and C risk reduction among injectors in the Seattle area. J. Urban Health. 2000;77:331–345. doi: 10.1007/BF02386744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trafton JA, Minkel J, Humphreys K. Determining effective methadone doses for individual opioid-dependent patients. PLoS. Med. 2006;3:1549–1676. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward J, Hall W, Mattick RP. Role of maintenance treatment in opioid dependence. Lancet. 1999;353:221–226. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05356-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin W, Hao Y, Sun X, Gong X, Li F, Li J, Rou K, Sullivan SG, Wang C, Cao X, Luo W, Wu Z. Scaling up the national methadone maintenance treatment program in China: achievements and challenges. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2010;39:29–37. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]