Abstract

Objective

Clinical decision support (CDS) is a powerful tool for improving healthcare quality and ensuring patient safety; however, effective implementation of CDS requires effective clinical and technical governance structures. The authors sought to determine the range and variety of these governance structures and identify a set of recommended practices through observational study.

Design

Three site visits were conducted at institutions across the USA to learn about CDS capabilities and processes from clinical, technical, and organizational perspectives. Based on the results of these visits, written questionnaires were sent to the three institutions visited and two additional sites. Together, these five organizations encompass a variety of academic and community hospitals as well as small and large ambulatory practices. These organizations use both commercially available and internally developed clinical information systems.

Measurements

Characteristics of clinical information systems and CDS systems used at each site as well as governance structures and content management approaches were identified through extensive field interviews and follow-up surveys.

Results

Six recommended practices were identified in the area of governance, and four were identified in the area of content management. Key similarities and differences between the organizations studied were also highlighted.

Conclusion

Each of the five sites studied contributed to the recommended practices presented in this paper for CDS governance. Since these strategies appear to be useful at a diverse range of institutions, they should be considered by any future implementers of decision support.

Introduction and background

Clinical decision support (CDS) represents a critical tool for improving the quality and safety of healthcare. CDS has been defined in many ways, but at its core, it is any computer-based system that presents information in a manner that helps clinicians, patients, or other interested parties make optimal clinical decisions. For the purposes of this paper, we will limit our attention to real-time, point-of-care, computer-based CDS systems, such as drug–drug interaction alerting, health maintenance reminders, condition-specific order sets, and clinical documentation tools. A substantial body of evidence suggests that, when well-designed and effectively implemented, CDS can have positive effects for healthcare quality, patient safety, and the provision of cost-effective care.1 2

Although the benefits of decision support are numerous, only a small number of sites in the USA have achieved significant success with it.3 A variety of challenges limit the wide adoption of CDS, but a critical one is the difficulty of developing and maintaining the required knowledge bases of clinical content.4 5 Effective CDS often requires extremely large knowledge bases of clinical facts (eg, drug-interaction tables). This content must be engineered (or purchased) and must also be kept current as clinical knowledge, guidelines, and best practices evolve.6 The knowledge bases that are developed must reflect both universal best practices and local practices and needs. Knowledge management is an iterative process that involves both the creation of new content and the continuous review and revision of existing content.

To develop these clinical knowledge bases and ultimately work toward “meaningful use” of CDS, organizations must implement and operate governance processes for their clinical knowledge.5 7 These governance processes take many forms. Some organizations use existing clinical committees to develop and screen decision-support content (such as a Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee) or appoint a single person to review and approve content (such as the Chief Medical Informatics Officer), while others develop new committee structures along with intranet-based content creation, review, and approval systems. Governance can vary widely depending on the type and size of the organization. For example, large organizations, such as academic medical centers and government-run hospitals, can potentially develop and implement CDS internally, while smaller organizations, such as group practices and community hospitals, may need to rely on a partnership with a commercial vendor.

Careful consideration of governance issues when developing and implementing CDS can be as important as the quality of the decision support itself. In the absence of effective governance practices, implementation of CDS may fail, despite the purchase or development of a sophisticated system. A notable example of this issue is the decision-support system at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center that had to be shut down because of usability issues.8 Employing better governance practices throughout the design and implementation phases, such as increased end-user involvement, can potentially stave off these types of problems.

Although governance and other organization factors have been noted as an essential aspect of high-quality CDS 9 10 and requisite data warehousing and management,11 limited research exists about optimal and real-world CDS governance practices. Outside of the healthcare industry, a variety of models have been proposed to describe knowledge management and IT governance practices.12–14 These models emphasize the need for continuous knowledge management, the value of studying real-world governance best practices and the importance of well-planned implementation. Researchers also note the substantial investment required to implement IT and knowledge management systems and the uncertainty associated with these investments, further underscoring the need for effective governance.12 15 In order to establish effective governance practices and realize the potential of IT and knowledge management systems, a broad understanding of the institutional pressures organizations face and real-world assessment of these institutional pressures is both valuable and necessary.16

Any organization embarking on a new initiative to develop decision support (or simply expanding an existing mandate) faces the choice of how to design its governance structures and the underlying technology to support these efforts. In this paper, we show how five diverse healthcare organizations developed their governance structures and discuss some of the tools they are using to support these activities. We examine each organization's governance, content management, and technical approaches. After presenting the approaches, we synthesize the lessons learned and develop a set of recommended practices in the three areas. For the purposes of this paper, we refer to “governance practices” as any formal leadership structure, governing bodies, and institutional policies related to the development and implementation of clinical information systems. In general, “governance” refers to the process by which an institution decides on what content will be implemented and how this will occur. In contrast, “content management” refers to the organizational structures and clinical information systems used to view, manage, and update clinical content on an ongoing basis following implementation. Content management allows for continuous tracking of existing CDS systems and allows institutions to generate reports for committee review. In this paper, we analyze both of these interrelated issues at each of the participating sites.

Methods

This work is part of a larger initiative called the Clinical Decision Support Consortium.17 The Consortium is focused on sharing CDS content and is pursuing several related aims, including the creation of knowledge representation standards,18 development of CDS services, and execution of a number of demonstrations of Consortium decision-support content at sites across the country. One of the foremost aims of the Consortium, however, is the study of decision-support best practices including governance practices.19

Members of the Clinical Decision Support Consortium research team conducted three site visits and five comprehensive surveys (the three original sites plus two validation sites) at institutions across the country to learn about their CDS capabilities and governance practices with the goal of distilling a set of recommended governance and content management practices based on observations and interviews during field research. Our sampling strategy for these visits was purposive; we selected five exemplary institutions with a history of successful CDS research and utilization.

The team used the Rapid Assessment Process for all fieldwork.20 At each site visit, a team of four to seven researchers (physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and informaticians) traveled to the site and conducted interviews with decision-support developers and information system leaders, as well as observations of clinical end users. Interviews were tape-recorded, and detailed field notes were captured for each observation. Each day at midday and in the evening, the team debriefed and modified the approach as needed. During these meetings, the research team reviewed field notes, discussed their observations and worked to identify themes and recurring patterns. After returning from the site visit, audio recordings were transcribed, and field notes were typed. The research team, lead by trained ethnographers, identified themes in the data using a grounded theory approach. NVivo 8 qualitative data-analysis software (QSR International, Victoria, Australia) was used to facilitate the process. Field notes and transcripts of interviews were read into NVivo, and then recurring concepts and themes were identified by the team members using the software. The data collected during site visits covered the entire breadth of CDS, including issues such as user interface and technical considerations. For this analysis, only data coded under the themes of content management and governance were reviewed in detail.

After conducting the initial analysis in NVivo, and identifying several hundred concepts across several thousand lines of notes and transcripts, the team used a card-sorting technique to develop an initial set of governance and content-management practices we had observed in the field and then distilled these practices into a summary set of themes. We then developed questions based on these themes and sent written questionnaires to a purposive sample of five sites: three from our initial site visits and two new sites to validate and extend our initial findings. We also asked each site to fill out an inventory of decision-support content at their site based on the six key categories of CDS developed by Osheroff et al.21

The five organizations studied are Partners HealthCare System in Boston, Massachusetts; the Mid-Valley Independent Physicians Association (MVIPA) in Salem, Oregon; Vanderbilt Medical Group, in Nashville, Tennessee; Veterans Health Administration (VA), a national healthcare delivery organization headquartered in Washington, DC; and the University of Texas Physicians' Practice Plan, in Houston, Texas. Site visits were conducted at Partners HealthCare, MVIPA and the VA Health System in Indianapolis.

Based on these case studies, we develop a theoretical framework for studying decision-support governance and present a set of recommended practices that other institutions might consider as they develop their own governance approaches. Because formal governance models for decision support are relatively new, no interventional (or even wide-scale observational) evidence exists for the effect of various CDS governance practices, and there is no particular regulation relevant to such practices. Thus, for the purpose of this paper, we refer to “recommended practices” as practices which the sites identified as critical to their success and which appear to have face validity. We believe that this is the best proxy for consensus available, given the relative novelty of inquiry in the area of CDS governance.

Results

Overview of organizations

These five organizations encompass a variety of academic and community hospitals, and comparatively small and large ambulatory practices. They use both commercially available and in-house-developed clinical information systems. They also include for-profit, not-for-profit, and government-provided healthcare as well as the full gamut of medical and surgical clinical specialties. Their key characteristics are shown in table 1. We visited Partners, MVIPA, and the VA Health System in Indianapolis, Indiana. The University of Texas and Vanderbilt were used as our validation sites and were characterized through written questions and interviews.

Table 1.

Overview of the organizations' characteristics

| Mid-Valley Independent Physicians Association* | University of Texas Physicians' Practice Plan | Vanderbilt Medical Group | Partners HealthCare* | Veteran's Health Administration* | |

| Location | Salem, Oregon | Houston, Texas | Nashville, Tennessee | Boston, Massachusetts | National |

| Characteristics of setting | Community outpatient | Academic, outpatient | Academic | Academic | Government |

| Volume of care | Over 500 practitioners at 262 practices; more than 40 000 patients | More than 1200 practitioners at 88 clinics in 80 medical specialties and subspecialties | More than 1400 practitioners in 96 practice groups; 1.2 million clinic visits yearly; 52 000 inpatient admissions yearly | More than 7000 practitioners; 2.0 million ambulatory visits yearly; 200 000 inpatient admissions yearly | More than 17 000 practitioners in 1300 sites of care; 5.5 million patients; 62.3 million outpatient visits yearly; 590 000 admissions and 5 million inpatient bed days of care yearly |

| Clinical information systems | Uses NextGen Healthcare Information Systems EHR; supported by Mid-Valley Independent Physicians Association | 75% of all clinicians have used Allscripts EMR system, live since 2004; no paper charts (all paper information scanned in) | Internally developed EHR, StarChart, and internally developed care provider order entry, WizOrder | Integrated internally developed outpatient EHR, the Longitudinal Medical Record; patient access to online health record application | Computerized Patient Record System developed by VA available in all areas |

| Decision support characteristics | Built-in clinical decision support tools (eg, drug–drug interaction, health maintenance reminders, order sets); tailored clinical content for 14 specialties; patient care plan dashboard; prescribing module | Medication related CDS content (eg, drug–drug, drug allergy) purchased from Allscripts (little to no modifications); UpToDate access; Surescripts for prescriptions, lab results received electronically from Quest; order sets | Computerized provider order entry (over 1000 order sets and advisors); clinical reminders; barcode medication administration | Clinical alerts; order sets; comprehensive chronic disease-management systems for diabetes and coronary disease; outpatient results management application | Supports numerous types of CDS, such as clinical reminders, order checks, order menus, and record flags; chronic disease-management systems including patient registries; bar code medication administration; patient web portal with wellness reminders |

Site visit conducted.

EHR, electronic health record; EMR, electronic medical record.

In addition to the broad demographic characteristics in table 1, we found that each site had at least one example of each of the six decision-support types in the Osheroff taxonomy, suggesting that each site had sufficient breadth of content to necessitate some level of decision-support governance.

Despite having similar breadth of CDS, the sites varied dramatically in the depth of decision support they had. For example, the number of different condition-specific order sets ranged from less than 50 to more than 800, and the number of unique clinical alerts ranged from less than 50 to more than 7000. This pattern of differing “depths” of CDS implementation accounts in large part for the differences in the structure, complexity, and size of the clinical governance infrastructure that each organization has developed.

Governance approaches

All five sites in our analysis had at least some degree of decision-support governance, although the form and pattern of governance models differed greatly. Table 2 describes the approaches, including CDS-related staff, committees, governance process, tailoring of content, levels of governance, and tools for soliciting and managing user feedback. The five organizations are listed left to right across the top according to size, starting with the two smaller strictly ambulatory sites that use commercial systems. They are followed by the two academic health centers with locally developed inpatient as well as outpatient systems. The national VA health network, in the final column, is the largest and includes inpatient, outpatient, long term, and home-based care. Table 2 compares governance styles and structures across each of the five case studies. See appendix 1, available as an online data supplement (http://www.jamia.org), for further detail on the case studies.

Table 2.

Governance approaches at each of the five sites

| Mid-Valley Independent Physicians Association* | University of Texas | Vanderbilt | Partners* | Veterans Health Administration* | |

| CDS-related staff | A medical director of information systems and 13 informatics staff members help support the system | Most content is purchased, so CDS-focused staff is minimal | Large academic informatics staff, including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and informaticians | Physicians, pharmacists, nurses, informaticians, analysts, and software developers | National and local software developers, clinical subject-matter experts, and local clinical application coordinators |

| Committees | EHR Communications and Policy Committee comprising key Mid-Valley Independent Physicians Association staff and representatives from the Mid-Valley Independent Physicians Association board of directors helps guide ongoing CDS operations and development of new content. A Physician Advisory Committee discusses and prioritizes development activities. | Content governed by the Chief Information Officer and an ‘Allscripts Review Board’ composed of key clinical and administrative leaders from the practice, including six practicing physician representatives | Decentralized organization-wide committees for example, Patient Safety and Clinical Practice Committees. System-specific committees: Horizon Expert Documentation advisory board (nurse charting) and user groups (Horizon Expert Orders, StarPanel). Also pharmacy and condition specific groups for example, Medication Use and Safety Improvement, Patient Falls and Vascular Access Committees. Committees are not overseen by central authority and may not interact with one another. | Centralized organization, different teams concentrate on different clinical domains. For example, an enterprise-wide medication-related content group consists of pharmacists and physicians working in collaboration with engineers and broader clinical groups, such as an adult primary care expert panel, a diabetes panel, and a host of ad hoc clinical work groups. Committees/content groups regulated and coordinated by central authority. | At the local level (ie, individual VA site), clinical councils or boards, pharmacy and therapeutics committees, quality management committees, primary care committees, and/or clinical informatics committees. Nationally, a National Clinical Reminders Committee. |

| Process | Almost all content comes from EMR vendor. New development (eg, additional drug–drug interaction rules) is primarily based on requests made by member physicians. The user community includes subject matter experts (SMEs), who are polled or convened as necessary. | Content purchased from commercial vendor. Day-to-day CDS operations are run by a small team that is responsible for managing all servers, desktop support, and a help desk. Significant issues escalated to the Allscripts review board. | Relatively decentralized. Content is typically requested by end users or committees most familiar with that subset of available tools and developed in collaboration with informatics experts by that group, or centrally. | Full-time clinically trained subject matter experts (SMEs) work in small teams with knowledge engineers to develop and implement CDS, using a three-stage life cycle process of knowledge creation, knowledge deployment, and periodic review | Performance measures established nationally based on quality goals and utilization review; corresponding reminders are developed either locally or nationally. Local, regional, and national committees have input into the content developed. |

| Customization | Practices are permitted to develop their own content if desired, and NextGen system allows sufficient customization so specific templates, rules, and actions can be filtered to a specific practice without affecting others | Generally not permitted | Local customization is allowed within the constraints of the agreed upon standard practice (eg, a screening practice might vary by clinical unit, but all patients must still be screened) | Partners consists of a large number of hospital and outpatient sites, and, although they support local customization of content where necessary (eg, to adapt to differences in hospital formularies), common enterprise-wide content is preferred. | Governance for performance measures and drug–drug and drug-allergy checks at national level. Previously, sites developed local clinical reminders; national reminders are preferred. Order menus/sets, templates, and consult requests done at facility level. |

| CIS usage required | Use of CDSS encouraged | Use of CDSS encouraged, no paper chart | Use of CDSS encouraged | Mandated usage | Mandated usage |

| Review/monitoring | Regular review of EMR performance with reports issued | Monthly reports issued to clinics by vendor regarding EMR performance | Regular review of usage statistics and research project evaluations | Regular review of usage statistics when available and research project evaluations | Measure outcomes against national measures. Regular review of EMR performance with reports issued. |

| User feedback | Direct interaction between end users and the medical director and support staff through user-group meetings | Informal user feedback, surveys and help-desk issue tracking | Email, regular contact by content owners with the clinical teams, clinical user group meetings, and regularly scheduled review of content and usage statistics with the clinical teams | Applications have built-in features to enable users to provide granular feedback in response CDS interventions. Users are invited to participate in user groups and the content development process depending on interest/expertise. | Users interact primarily with local clinical application coordinators to provide feedback |

| References | 31–33 | 34 35 | 36 37 |

Site visit conducted.

CDSS, clinical decision support system; CDS, clinical decision support; CIS, clinical information systems; EHR, electronic health record; EMR, electronic medical record.

Variation in governance strategies was observed across the five sites. CDS-related staff ranged from a small staff responsible for overseeing a vendor system to large academic informatics departments that included numerous clinicians, informaticians, and software developers. Most sites employed the use of committees to govern development, implementation, and maintenance of CDS systems, although committee structure and overall organization varied. In some cases, content was purchased from an outside vendor, and in others it was developed by in-house staff based on institutional needs. Sites also varied in the degree to which they allowed tailoring of CDS content in individual practices or hospital services. Some form of regular review was common across all sites studied, although mechanisms of user feedback varied significantly in form and frequency.

One particularly notable finding was that governance approaches differed substantially between institutions relying on vendor-based clinical information systems and those with “home-grown” internal clinical information systems (CIS). These differences were largely related to each type of institution's involvement in CDS development, implementation and management. Organizations that rely on vendor-based CDS require governance structures largely limited to collaboration with vendors and ongoing day-to-day operational management. In contrast, organizations with internally developed systems are responsible for the entire process of development, implementation, and ongoing management and assessment. These fundamental differences result in diverging governance practices, which are summarized in table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of governance practices at sites with internal CIS (clinical information systems) development and vendor-based CIS

| Governance | Internally developed CIS | Vendor-based CIS |

| Clinical decision-support-related staff | Require large staff with specialized clinical knowledge | Fewer staff members who support system and collaborate with vendor |

| Committees | More, specialized committees | Fewer (possibly one) centralized committee(s) |

| Process | Content developed by committee, employing subject matter experts and knowledge engineers | All or almost all content comes from content vendor; system operations may be run locally |

| Customization | Permitted, although standardization may be preferred | Limited or not permitted |

| Central governance | Content managed through organization-wide committees with distinct specializations | Content managed centrally by vendor |

| CIS usage required | Use of clinical decision-support system more likely to be mandated | Use of clinical decision-support system more likely to be encouraged |

| Review/monitoring | Regular usage monitoring and research evaluation | Regular reports from vendors |

| User feedback | Variety of tools employed | Variety of tools employed |

Overview of content-management approaches

Our research findings clearly revealed that sites needed coordinated ways to manage their decision-support content, particularly as the amount and complexity of the content grew.

At Partners, a great deal of the CDS content was developed as part of research projects, and balancing research and operational decision-support projects has been challenging, as research content must be maintained (or decommissioned) after the research project ends. Over the last 5 years, with the maturation of the knowledge management group's processes, content is increasingly re-evaluated on a periodic basis, which includes analysis of usage data, such as acceptance and override rates for alerts.22 23 The most robust review mechanisms are in place for formulary drug information (dose and frequency lists), drug–drug interaction rules,24 age- and renal-based drug dosing guidance rules,25 and health maintenance reminders. For these assets, Partners conducts regularly scheduled reviews of content, at differing frequencies. In addition, on-demand reviews are prompted by user feedback and external events gleaned from regular scans of health-information sources, such as FDA and pharmaceutical company announcements and the medical research literature.

Vanderbilt has several mechanisms to assess ongoing proper functioning of clinical content. Surveillance data are collected on order set usage, responses to decision-support pop-up alerts, and other CDS items to adjust the support to the desired outcome. Vanderbilt conducts regular reviews of content and then updates the content as clinical evidence surfaces that would necessitate a change. Vanderbilt prioritizes changes based on quality, safety, clinical volumes, and cost/benefit.

In contrast to the other academic institutions, the University of Texas, Houston Physicians' Practice Plan relies heavily on Allscripts' content, and updates are tied to the Allscripts' release schedule. The Practice Plan conducts surveys of clinical users and creates monthly reports that provide all clinics with a breakdown of the utilization of all aspects of the EHR (electronic health record) (eg, percentage of prescriptions written electronically).

CDS capabilities at the VA are constantly being updated and revised to reflect internal research activities, review of performance measures, input from regulatory groups, networking with academic affiliates, changing emphasis of national program and patient priorities, and involvement in national professional societies and working groups. Evidence-based guidelines from nationally recognized authorities are also reviewed regularly for inclusion. Additionally, the VA national pharmacy program is pursuing integration of a commercially available database for drug–drug/allergy interactions, which would be maintained and periodically updated. Evaluation of the effectiveness of the CDS is indirect and based on the measurement of outcomes it was designed to impact.

Finally, at MVIPA, the primary method of evaluating the effectiveness of CDS is ongoing field testing. Content is updated periodically through the NextGen release cycle and is first tested by MVIPA staff. Design changes that affect clinical content are reviewed by the medical director of information systems. The director also monitors regulatory requirements and prioritizes updates according to their effective dates and their impact.

Comparison of content-management approaches

The content-management practices of the organizations differed significantly based on the nature of the organizations. Academic medical centers reported that much of their content was, at least initially, developed by researchers as a part of research projects. Identifying and maintaining this content, particularly after research projects concluded, appeared to be challenging. Sites also reported developing content based on user requests, regulatory and quality reporting requirements, and other organizational priorities.

All sites reported some form of ongoing content review, but the frequency and regularity of these reviews varied. Some organizations carried out an annual review, while other organizations reviewed content based on user feedback or as new evidence became available. Sites which relied more heavily on vendor content were more likely to report periodic updates or refreshes, often tied to vendor release schedules.

Sites also mentioned and underscored the importance of field-testing content and listening and responding to user feedback. These feedback mechanisms ranged from passive receipt of reports to active feedback tools embedded in the EHR and periodic site visits and assessments. Some sites also reported monitoring usage of content in order to prioritize the most highly used content.

In addition to direct CDS-related evaluation, some sites (particularly the VA) reported a strong focus on associated quality measures. The VA also emphasizes standard practice and common data elements within and across their system of care, and is in the process of standardizing such practices when there is evidence or experience to support such efforts. Other sites, including Partners, reported less standardization.

Discussion

Based on our data collection and analysis, we identified a set of recommended practices for CDS governance and content management. These strategies are designed for organizations developing or expanding CDS efforts at their sites. Based on the sites we studied, these practices seem to be effective general approaches to CDS governance. As evidenced in the case studies, however, decision support is an intensely local phenomenon,26 and as such, sites may need to tailor or selectively adopt these practices to develop solutions that work for them.

Recommended practices for governance

Delivering excellent CDS requires addressing many governance issues. Among these are defining who will determine if, when, and in what order new decision support will be added; developing a process for assessing the impact of new decision support on information systems' response time and reliability; building tools to enable tracking of what decision support is in place; developing an approach for testing decision support in silico; defining approaches for dealing with rules that interact; developing solid processes for getting feedback from users and letting them know what changes have been made in the underlying systems; and building tools for automated monitoring of decision support. These recommended CDS governance practices are summarized below.

Prioritize the order of development for new CDS and delegate content development to specialized working groups

One of the most important issues is developing a sound approach for determining what new decision support will be added and establishing a timeline for development and implementation. A high-level group should prioritize new and ongoing work (eg, blood transfusion-related CDS versus CDS around medications in the neonatal intensive care unit) while specific content work groups develop the prioritized content. Ideally, knowledge-management work groups should consist of local experts in each clinical content area. This process may be carried out internally or delegated to a vendor.

Consider the potential impact of new CDS on existing clinical information systems (such as the EHR application or computerized provider order entry system)

With all new CDS content or functionality it is vitally important to consider the potential impact on all related systems upon implementation. Organizations need a sound process in place for assessing any potential impact on their larger clinical information system ecosystem (ie, EHR, computerized provider order entry, laboratory results system). For example, what are the effects of a new intervention on usability, response time and reliability of the surrounding information system? Each organization is unique in institutional structure and culture, and thus assessments must be performed de novo for each institution, regardless of whether a new CDS is internally developed or purchased from a vendor. Careful evaluation is necessary to avoid potentially problems with related and interacting CIS.

Develop tools to monitor CDS inventory, facilitate updates, and ensure continuity

Robust tools must be built to monitor and maintain existing decision support. These tools facilitate tracking of when changes were made, when updating is due, and who is responsible for these activities within an organization. Having one person who can review all content (eg, a chief informatics officer) is very helpful, but when the amount of content increases, this may not be possible. Furthermore, planning for inevitable leadership transitions is essential in order to ensure continuity and maintain up-to-date content. The volume of clinical content and rule logic contained in these systems makes these tools necessary for ensuring the system is up to date and functioning properly, and for guiding future development and implementation.

Implement procedures for assessing the impact of changes and additions to CDS system on the system's own functionality

Within any existing CDS system, it is crucial to test decision support before it “goes live” to reduce the likelihood that it will create problems with the existing decision support, or slow down the live system.27 A related issue is that many rules interact, and as more rules are added, interactions become more frequent, one example being rules relating to reducing cholesterol levels in patients with diabetes and coronary disease.28 To the extent possible, conflicts and interactions should be addressed in the background so that users are not confronted with redundant or inconsistent warnings. Committees may be required to interact to resolve conflicts fairly and transparently. Specific CDS system testing and rule interaction resolution (related to the stability of the CDS system itself) should be carried out in addition to testing of the impact of CDS systems on all clinical information systems (as outlined in recommendation 2).

Provide multiple robust channels for user feedback and the dissemination of systems-related information to end users

Building processes that make it possible for users to deliver feedback about the decision support is critical to user acceptance. When a significant issue or problem is identified, it is also crucial to have a process for responding to user suggestions and making appropriate changes. Some organizations such as Vanderbilt have gone so far as to deliver routine, individual reports back to providers after such feedback has been addressed. All organizations will need approaches for notifying providers of important changes in decision support (eg, new alerts, changes to the interface).

Develop tools for ongoing monitoring of CDS interventions (eg, rule firings, user response)

Approaches that enable automated monitoring of systems will be increasingly important, so that one can determine how often rules are firing and how users are responding to them.29 Flags should be set to enable the counting of rule firing, and approaches are needed to track user responses, including when users cancel or “escape” following a warning. Often, a seemingly minor change can have a major impact on how many warnings are being delivered, and even on overall system performance. In addition to ongoing monitoring of CDS inventory (as outlined in Recommendation 3), monitoring of CDS interventions is necessary for properly assessing the impact of CDS on clinician behavior and patient care. The combination of these tools provides continuous system feedback that can guide changes and additions to the CDS system.

Recommended practices for content management

The development and implementation of effective CDS also depend on sound content-management strategies. The large knowledge bases required for robust CDS necessitate frequent and thorough management in order to keep clinical content up to date. Based on our comparison of the five case studies, we define four recommended practices for content management.

Delineate the knowledge-management life cycle

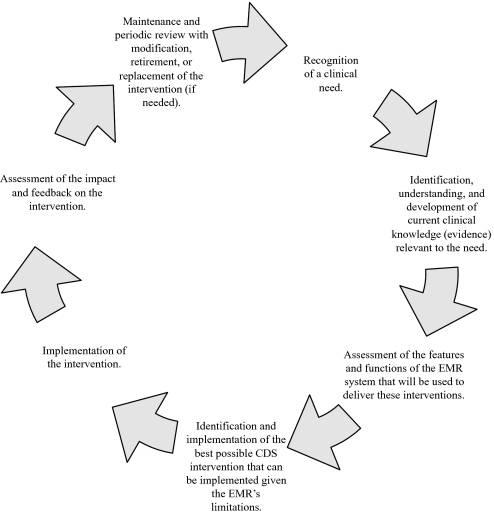

The knowledge-management life cycle is an iterative and cyclical process for maintaining the large knowledge bases that CDS requires. The life cycle typically extends from recognition of a clinical need to maintenance and periodic review with modification, retirement, or replacement of the intervention as needed. Every site had at least some component of a knowledge-management life cycle (even if only the creation part); however, we found seven commonly occurring life-cycle phases, shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Knowledge-management life cycle. CDS, clinical decision support; EMR, electronic medical record.

Develop tools to facilitate content management

Several of the sites reported having special-purpose software tools for managing content throughout this knowledge management life cycle. The availability and use of these tools, when well designed, can improve efficiency, allow for asynchronous communication, and ensure that content is periodically reviewed and kept up to date.30 Such tools can also enhance the auditability of content, as decisions can be traced.

Enable ongoing measurement of acceptance and effectiveness of CDS interventions

Several of the studied sites had robust measurement programs, where the acceptance and effectiveness of their content are measured after roll-out and on an ongoing basis. Measurement allows content developers to assess the impact of their content and to identify opportunities for improvement. Common metrics included firing rate, acceptance rate, analysis of override reasons, and measurement of the decision support's effects on intermediate processes, and ultimately its effects on patient safety and quality of care.

Implement user-feedback tools that encourage frequent end-user input

All of the sites provided some capability for user feedback, ranging from feedback buttons embedded in the EHR application to email, helpdesk query tracking, and clinical representation on committees. Listening and responding to feedback is an important tool for product improvement. It also has the added advantage of fostering a sense of ownership of the product by end users when they feel that their input is valued.

Considerations for smaller sites

The governance and content-management strategies we identified are most applicable for large sites with mature and robust CDS. However, small sites that are earlier in the process of developing CDS also face similar governance challenges. The primary differences are that, in general, most small sites have a limited ability to develop and monitor CDS and, as a result, tend to purchase their decision support from commercial content suppliers, rather than developing the content themselves, and tend to rely on general-purpose software tools and built-in EHR functions. In a small practice environment, some tasks, such as monitoring inventory and user feedback, may be simpler to accomplish. Overall, small sites must confront the same issues but with the added challenge of limited financial resources and personnel.

Limitations and future work

The purpose of this project was to develop an initial framework for thinking about governance for CDS and to identify a set of recommended practices based on our work. However, this approach has several important limitations, which correlate with opportunities for future work. First, we presented data on a total of five exemplary sites which are purposefully non-representative of typical practice—we believe that this approach maximized what we could learn, but it also limits the generalizability of our data. Further exploration of more sites (especially sites with more typical CDS environments) would contribute to a more well-rounded understanding of CDS governance practices, as widely applied. In addition, it may also be worthwhile to expand our assessment of CDS governance practices to include the role of professional organizations, national regulatory bodies, and clinical content vendors. The governance issues discussed in this paper are not limited to commercial EHR vendors and healthcare institutions, and in the future, we hope to investigate the role of these additional key plays in CDS development and implementation. Finally, the sites studied included only US institutions, which further limits the generalizability of our findings—future study of an internationally representative collection of sites is also likely to be fruitful.

In addition, although we employed a well-established method of qualitative data collection (RAP), complementary future quantitative research could shed further light on CDS governance practices and enhance generalizability. We identified recommended practices based on consensus and expert opinion, and as a result, some effective practices may have been missed. Ideally, these practices would be studied further through a combination of observational or even experimental studies in order to more rigorously quantify the methods for and value of governance. Because of the present relative paucity of sites with advanced (or even formal) governance structures, it may yet be premature to perform such a study, but once there exists a sufficient set of institutions with reasonably robust governance practices, we believe that such a study would add great value to the literature.

Finally, we were not able to characterize the cost of CDS governance, or to study the financial implications of different governance approaches. It would be valuable to assess the comparative cost of different approaches to CDS governance across multiple institutions. However, given the small number of sites with extensive experience in CDS governance and the difficulty in determining costs of large and multifaceted governance structures, such an analysis was not possible at this time but would be a useful future research endeavor.

Conclusions

We have synthesized five case studies and identified a set of recommended practices for governance and content management. The five sites we studied were quite diverse; however, they had also learned many overlapping and complementary lessons about governance for CDS. Although the needs of every implementer of decision support are different, we believe that many of these recommended practices may be nearly universal and that all implementers of decision support should consider employing them.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the participants who allowed us to observe and interview them during our research. We also acknowledge and appreciate the assistance of J Coury, of the Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research, who provided editorial assistance as we prepared this manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by AHRQ contract #HHSA290200810010 and NLM Research Grant 563 R56-LM006942.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Approval was provided by Partners HealthCare; approval was also obtained at some of the sites (where not waived to Partners).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Garg AX, Adhikari NK, McDonald H, et al. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA 2005;293:1223–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, et al. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ 2005;330:765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, et al. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:742–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sittig DF, Wright A, Osheroff JA, et al. Grand challenges in clinical decision support. J Biomed Inform 2008;41:387–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright A, Bates DW, Middleton B, et al. Creating and sharing clinical decision support content with Web 2.0: Issues and examples. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:334–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sittig DF, Wright A, Simonaitis L, et al. The state of the art in clinical knowledge management: an inventory of tools and techniques. Int J Med Inform 2009;79:44–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bates DW, Kuperman GJ, Wang S, et al. Ten commandments for effective clinical decision support: making the practice of evidence-based medicine a reality. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2003;10:523–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrissey J. Harmonic divergence. Cedars-Sinai joins others in holding off on CPOE. Mod Healthc 2004;34:16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teich JM, Osheroff JA, Pifer EA, et al. CDS Expert Review Panel Clinical decision support in electronic prescribing: recommendations and an action plan: report of the joint clinical decision support workgroup. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2005;12:365–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osheroff JA, Pifer EA, Teich JM, et al. Outcomes with Clinical Decision Support: An Implementer's Guide. Chicago, IL: Health Information Management Systems Society, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watson HJ, Fuller C, Ariyachandra T. Data warehouse governance: best practices at Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina. Decision Support Systems 2004;38:435–50 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burstein F, McKay J, Zyngier S. Knowledge management governance: a multifaceted approach to organizational decision and innovation support. Proceedings of the IFIP Conference on Decision Support Systems. Prato, Italy; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onions PEW, de Langen R. Knowledge Management Governance. Budapest, Hungary: 7th European Conference on Knowledge Management (ECKM 2006), Cornivus University, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grant G, Brown A, Uruthirapathy A, et al. An Extended Model of IT Governance: A Conceptual Proposal. Americas Conference on Information Systems. Keystone, Colorado; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nunes MB, Annansingh F, Eaglestone B, et al. Knowledge management issues in knowledge-intensive SMEs. J Doc 2006;62:101–19 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobson DD. Revisiting IT Governance in the Light of Institutional Theory. 42nd Hawaii International Conference on Systems Science. Hawaii: Waikoloa, Big Island, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Middleton B. The clinical decision support consortium. Stud Health Technol Inform 2009;150:26–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boxwala A, Rocha B, Maviglia S, et al. Multilayered Knowledge Representation as a Means to Disseminating Knowledge for Use in Clinical Decision-Support Systems. Orlando, FL: Spring AMIA Proc, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ash J, Sittig DF, Dykstra R, et al. Identifying best practices for clinical decision support and knowledge management in the field. Stud Health Technol Inform 2010;160:806–10 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McMullen C, Ash J, Sittig D, et al. Rapid assessment of clinical information systems in the healthcare setting: an efficient method for time-pressed evaluation. Methods Inf Med 2010;50(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osheroff J, Pifer E, Teich J, et al. Improving Outcomes with Clinical Decision Support: An Implementer's Guide. Chicago, IL: HIMSS, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shah NR, Seger AC, Seger DL, et al. Improving acceptance of computerized prescribing alerts in ambulatory care. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006;13:5–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abookire SA, Teich JM, Sandige H, et al. Improving allergy alerting in a computerized physician order entry system. Proc AMIA Symp 2000:2–6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paterno MD, Maviglia SM, Gorman PN, et al. Tiering drug–drug interaction alerts by severity increases compliance rates. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009;16:40–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palchuk MB, Seger DL, Alexeyev A, et al. Implementing renal impairment and geriatric decision support in ambulatory e-prescribing. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2005:1071. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller RA. Computer-assisted diagnostic decision support: history, challenges, and possible paths forward. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2009;(14 Suppl 1):89–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell EM, Sittig DF, Guappone KP, et al. Overdependence on technology: an unintended adverse consequence of computerized provider order entry. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2007:94–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ganda OP. Refining lipoprotein assessment in diabetes: apolipoprotein B makes sense. Endocr Pract 2009;15:370–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sittig DF, Campbell E, Guappone K, et al. Recommendations for monitoring and evaluation of in-patient computer-based provider order entry systems: results of a Delphi survey. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2007:671–5 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sittig DF, Wright A, Simonaitis L, et al. The state of the art in clinical knowledge management: an inventory of tools and techniques. Int J Med Inform 2010;79(1):44–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller RA, Waitman LR, Chen S, et al. The anatomy of decision support during inpatient care provider order entry (CPOE): empirical observations from a decade of CPOE experience at Vanderbilt. J Biomed Inform 2005;38:469–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geissbuhler A, Miller RA. Distributing knowledge maintenance for clinical decision-support systems: the ‘knowledge library’ model. Proc AMIA Symp 1999:770–4 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiu KW, Miller RA. Developing an advisor predicting inpatient hypokalemia: a negative study. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2007:910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldman DS, Colecchi J, Hongsermeier TM, et al. Knowledge management and content integration: a collaborative approach. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2008:953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuperman GJ, Marston E, Paterno M, et al. Creating an enterprise-wide allergy repository at Partners HealthCare System. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2003:376–80 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fung CH, Tsai JS, Lulejian A, et al. An evaluation of the Veterans Health Administration's clinical reminders system: a national survey of generalists. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:392–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asch SM, McGlynn EA, Hogan MM, et al. Comparison of quality of care for patients in the Veterans Health Administration and patients in a national sample. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:938–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.