Abstract

Alcohol abuse and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection are major public health problems and frequently coexist in the same individual. Although several studies have shown a significant association between alcohol consumption and the risk of being infected with HIV, it is unclear whether this association is due to behavioral and/or biomedical mechanisms. Studies of HIV-infected patients are inherently limited in their ability to control for variables such as timing and dose of HIV exposure, nutrition, concurrent use of drugs of abuse, use of anti-retroviral therapy, and the frequency of alcohol consumption and amount of alcohol consumed. In order to study the impact of alcohol on HIV infection, we developed a model of chronic alcohol consumption in rhesus macaques monkeys (Macaca mulatta) infected with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), a lentivirus closely related to HIV that infects and destroys CD4+ cells and produces a progressive immunodeficiency representative of HIV disease. Using this model, our studies have shown that plasma viral loads are significantly higher in alcohol-consuming macaques at 60–120 days after SIV infection (viral set point) than in control animals. The viral set point has been shown to be predictive of disease progression, and in our studies, alcohol consumption was associated with accelerated disease progression to end-stage disease. The rhesus macaque SIV model should be useful in identifying the mechanisms by which alcohol increases the viral load of HIV, affects HIV-associated comorbidities, and influences the efficacy of anti-retroviral therapy.

HIV AND ALCOHOL

Alcohol abuse and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection are common in the US population. At present, more than 1.1 million US citizens are infected with HIV and about 40,000 new cases of HIV infection are reported annually (1). According to the findings of the National Longitudinal Epidemiology Survey, almost 1 in 2 adult Americans (44%) actively consume alcoholic beverages, with an estimated 14 million Americans suffering from alcohol abuse and dependence (2). It is therefore not surprising that a significant number of HIV-infected individuals also suffer from alcohol abuse. One study found that 82% of HIV-infected patients consume alcohol, and that 41% can be classified as hazardous drinkers (3). Because alcoholism and HIV infection frequently co-exist in the same individual, it is important to study the possible interactions between these two epidemic diseases affecting public health. Although there has been remarkable progress in studies of HIV infection, very little is known about the potential effect of alcohol consumption on the rate of HIV transmission and/or its effects on disease progression. Such information is needed to reduce the incidence of HIV infection and to develop effective treatment strategies for it.

Several reports have described a significant association between alcohol consumption and the risk of being infected with HIV. Numerous studies have reported that alcohol use increases the likelihood of engaging in risky sexual behavior, such as having unprotected sex with multiple or unfamiliar partners (4–6). Although risky sexual behavior and alcohol use have been linked to HIV infection, it is unknown whether alcohol consumption directly increases the likelihood of disease transmission or progression in individuals exposed to HIV.

Bagasra et al. have shown that alcohol administration to HIV-seronegative humans significantly increases HIV replication in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) when these cells are isolated and infected in vitro (7). However, Cook and colleagues reported individual variation in healthy volunteers, with only a subset of subjects exhibiting an increase in HIV replication with alcohol ingestion (8). Alcohol has also been shown to suppress host immune responses to HIV antigens in vitro. Nair et al. reported that alcohol selectively impairs the in vitro antigenic proliferative response to HIV env-gag peptide and natural killer (NK) cell activity by lymphocytes obtained from patients infected with HIV (9). Alcohol has also been reported to adversely affect HIV disease progression. Fong et al. described an alcohol-abusing patient with HIV infection who developed accelerated disease progression to AIDS over a 3-month period (10). Pol et al. found an increase in blood CD4+ lymphocytes in alcohol-abusing HIV-infected patients during alcohol withdrawal (11). Alcohol abuse has also been shown to exacerbate indices of HIV-induced dementia (12–14). Additionally, moderate to heavy alcohol consumption has been shown to be positively correlated with vaginal shedding of HIV in patients receiving anti-retroviral therapy, even after adjustment for medication compliance (15).

Epidemiologic studies to date have not uniformly reported that alcohol use accelerates the progression of HIV disease to AIDS or causes a worsened outcome (16, 17). It is important to note that studies of the effects of alcohol and HIV interactions in human subjects are confounded by numerous factors, including variations in the frequency, type, and amount of alcohol consumed, differences in the infecting HIV strains, the route and frequency of HIV exposure(s), and variations in the type, side effects of, and patient compliance with anti-retroviral therapy. Recently, a significant association between heavy alcohol consumption and lower levels of CD4+ T cells has been reported among HIV-infected alcoholic patients not receiving anti-retroviral therapy (18).

MODEL SYSTEM

The SIV macaque model of HIV infection provides an excellent means to study the interactions of alcohol and SIV infection in a controlled and monitored environment. Simian immunodeficiency virus consists of a group of lentiviruses that are structurally, biologically, antigenically and genetically related to HIV (19). Critical to the use of SIV-infected nonhuman primates as a model of human HIV infection is the similar tropism to and infection by these viruses of CD4+ cells, resulting in acquired immunodeficiency that progress to AIDS with the occurrence of opportunistic infections (20, 21). Use of the SIV model offers several distinct advantages over human studies in identifying a link between alcohol consumption and susceptibility to and/or progression of HIV infection. Most importantly: 1) the time and route of SIV infection are known; 2) variables such as nutrition and behavior can be monitored and controlled; 3) the timing and quantity of alcohol administration before and during infection can be experimentally determined and manipulated; 4) longitudinal studies of the impact of alcohol on the clinical course of infection from its onset are feasible due to the shortened duration of the illness (median survival < 1 year); and 5) studies can be performed in either the absence or presence of anti-retroviral therapy. For these reasons we have developed a chronic model of alcohol delivery in combination with SIV infection in the rhesus macaque.

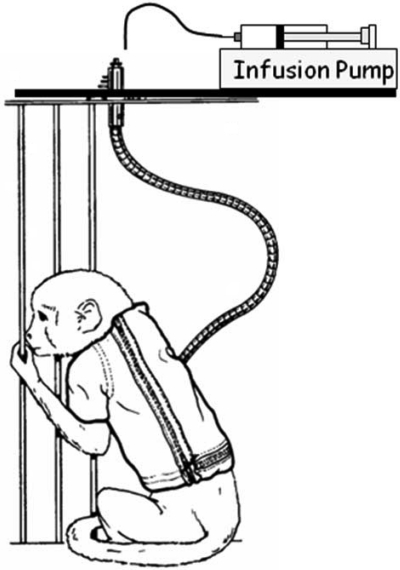

Our model system utilizes male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) of Indian origin that are 4–6 years of age. The monkeys are fed a commercial primate chow supplemented with fruit, and are provided with water ad libitum throughout our studies. In addition, animals receive ethanol or isocaloric sucrose via a permanently indwelling intragastric catheter for 4 or 7 consecutive days per week, to achieve a plasma ethanol concentration of 0.23–0.27% during a 5-hour session (22). Animals are fitted with a catheter-protecting jacket at 2 weeks prior to and with a tether 1 week prior to surgical implantation of the intragastric catheter. Tethers are long enough to allow animals to freely move about their cages, and are attached to a swivel that is in turn attached to the top of the animal's cage. The catheter is routed through the tether and attached to the swivel (Figure 1). At 3 months after the beginning of ethanol or sucrose administration, animals are inoculated intravenously with SIV.

Fig. 1.

Model for the controlled delivery of alcohol or sucrose in the home cage of conscious rhesus monkeys.

EFFECT OF ALCOHOL ON SIV

The monkeys' plasma ethanol concentrations reach a plateau between 1.5 and 2 hours into the ethanol infusion, and are maintained within or near the target range for the remainder of the 5-hour session (22). Once ethanol delivery is terminated, plasma ethanol concentrations progressively decrease to less than 10 mM by 6 to 8 hours and reach undetectable values by the next morning. During ethanol delivery, animals show signs of intoxication such as decreased activity and minor lack of coordination. In this cohort of animals, body weight in alcohol- and sucrose-treated animals did not differ during the first 300 days of SIV infection. However, at end stage, alcohol-treated animals had a tendency for greater weight loss than did control animals (23). Furthermore, in a larger study, we found alcohol-treated animals with SIV infection had a lower body weight and body mass index than did comparable control monkeys with end-stage disease (24). These and other data indicate that muscle wasting may be more prevalent in our SIV-infected animals consuming alcohol.

Lymphocyte subset analysis shows that CD4+ lymphocyte numbers are lower in SIV-infected animals. This decrease in CD4+ lymphocyte counts is also sufficient to decrease the ratio of CD4+ to CD8+ cells in the SIV-infected animals as compared with the SIV-negative animals. This ratio does not differ between SIV-infected alcohol- and sucrose-treated animals (22).

Each animal inoculated with SIV becomes infected as evidenced by persistent detection of virus in the plasma. Plasma SIV RNA levels are statistically increased significantly in alcohol-consuming animals in the asymptomatic stage of infection during a period when viral set point is predictive of disease progression (23). A high plasma viral load during this time of infection is associated with accelerated disease progression to end-stage disease (25, 26). In one of our initial studies, the median time of survival after SIV infection was 374 days in ethanol-treated animals, as compared with 900 days in the sucrose control group (P < 0.05) (23).

CONCLUSION

The impact of alcohol consumption on HIV disease transmission, pathogenesis, and progression has been difficult to assess in human studies. Apart from its close similarity to HIV infections, the SIV model in rhesus monkeys offers several advantages in identifying a potential link between alcohol consumption and HIV disease transmission and progression to AIDS. These include the ability to: 1) control the time and route of infection; 2) monitor and control nutritional and behavioral variables; 3) manipulate and control the timing and quantity of alcohol consumption; 4) conduct longitudinal studies, since the duration of infection from its inception to terminal disease with virulent strains of SIV is typically less than 2 years; and 5) perform studies in the absence or presence of anti-viral therapy. These advantages make the rhesus monkey SIV model attractive for investigating the impact of alcohol in the progression of HIV.

The major finding of our investigations is that progression to end-stage disease in SIV-infected animals is accelerated by chronic binge-equivalent alcohol administration as compared with SIV-infected control animals receiving isocaloric sucrose. The median time of survival for alcohol-treated animals was 2.4 times less than that of animals receiving isocaloric sucrose. Accelerated progression to end-stage SIV disease in alcohol-treated animals was found to be associated with a higher plasma viral load during the critical early asymptomatic stage of infection than the viral load in the control group of animals. This association is consistent with previous studies showing higher viral set points in animals that progress more rapidly to end-stage disease (25, 26). Our finding that alcohol-consuming animals infected with SIV have higher plasma viral loads is also consistent with other recent reports (27, 28).

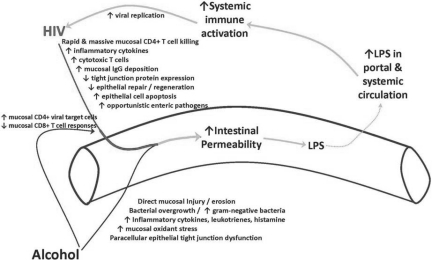

Defining the mechanisms responsible for the increased viral set point and more rapid disease progression observed in our model system will require further study. Our current working hypothesis focuses on the effects of both alcohol and SIV/HIV on the integrity of the mucosal immune system of the gastrointestinal tract. Alcohol consumption has been shown to compromise intestinal barrier function. Metabolism of alcohol by bacteria and intestinal epithelial cells can result in the accumulation of acetaldehyde, which disrupts epithelial tight junctions (29). It is also known that alcohol can promote the growth of gram-negative bacteria in the intestine, which may result in the accumulation of endotoxin. The alcohol-induced increase in intestinal permeability leads to increased transfer of endotoxin and other antigens into the systemic circulation, triggering a cascade of inflammatory responses. Recently, our group reported a higher percentage of SIV target cells (memory CD4+ T-cells) in the gut accompanied by a higher percentage of effector CD8+ T-cells (which probably play a role in controlling virus replication) in alcohol-consuming SIV-infected macaques (30). Interestingly, recent studies indicate that intestinal epithelial barrier function may play a central role in disease progression in HIV (31). The gastrointestinal mucosa is a main target of HIV infection (32), which results in damage to the intestinal epithelial microenvironment and increases the permeability of the intestinal epithelium. Human immunodeficiency virus-induced disruption of the epithelial barrier also leads to translocation of luminal antigens such as endotoxin across the intestinal epithelium. These events result in chronic, systemic immune activation, which is a main driving force for HIV replication and disease progression.

Thus, alcohol-induced leakage in the gut via the production of acetaldehyde would also lead to an increase in target cells for HIV (activated CD4+ T cell), which would further enhance viral replication and amplify the injury to the gut and enhance intestinal permeability. The culmination of these events would promote systemic inflammation, viral replication, and disease progression (Figure 2). Novel therapeutic approaches might then be focused on restoring the immunologic and epithelial integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier.

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram showing the separate and combined effects of alcohol and HIV on intestinal permeability resulting in systemic immune activation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by Grant AA009803 from the US Public Health Service.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest: None disclosed.

DISCUSSION

Blaser, New York: That is a very impressive result that you are showing. Do you know whether it's alcohol that's doing this, or could it be acetaldehyde, a metabolite of alcohol, which is converted in the intestine?

Nelson, New Orleans: As you point out, bacteria and intestinal epithelial cells can metabolize alcohol, resulting in the accumulation of acetaldehyde in the gastrointestinal tract, which can then disrupt epithelial tight junctions resulting in the translocation of endotoxin and other antigens into the circulation. These events would then trigger a systemic inflammatory response and drive viral replication in the infected host. In addition, alcohol, but not acetaldehyde, has been shown to suppress host immune responses to HIV antigens in vitro. It is likely that there are multiple pathways that lead to the increase in viral set point that we observed in our studies.

Palmer, New York: There are other agents that interfere with the integrity of the gastrointestinal tract, such as nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents (NSAIDs) that increase the absorption of those large sugars and so forth. Would you suppose that they would predispose to the same effects in human patients?

Nelson, New Orleans: Both SIV and HIV infection by themselves have been shown to increase gut permeability and increase lipopolysaccharide levels in the systemic circulation. Plasma LPS levels correlate with systemic immune activation, which then drives chronic SIV/HIV infection. As previously stated, alcohol also causes a “leaky” gut, which may further enhance both local and systemic inflammation and promote SIV/HIV replication. One might hypothesize a similar effect with other agents, such as NSAIDs, if they similarly increase gut permeability.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2007. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report; p. 19. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stinson FS, Yi HY, Grant BF. Drinking in the U.S: main findings from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiological Survey, Vol 99-3519. U.S. Alcohol Epidemiologic Data Reference Manual, U.S. Government Printing Office. 1997:3519. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lefevre F, O'Leary B, Moran M, et al. Alcohol consumption among HIV-infected patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:458–60. doi: 10.1007/BF02599920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stall R, McKusick L, Wiley J, et al. Alcohol and drug use during sexual activity and compliance with safe sex guidelines for AIDS: the AIDS Behavioral Research Project. Health Educ Q. 1986;13:359–371. doi: 10.1177/109019818601300407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKusker J, Westenhouse J, Stoddard AM, et al. Use of drugs and alcohol by homosexually active men in relation to sexual practices. J Acq Immun Def Synd. 1990;3:729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trocki KF, Leigh BC. Alcohol consumption and unsafe sex: a comparison of heterosexuals and homosexual men. J Acq Immun Def Synd. 1991;4:981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bagasra O, Kajdacsy-Balla A, Lischner HW, et al. Alcohol intake increases human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:789–97. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.4.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook RT, Stapleton JT, Ballas ZK, et al. Effect of a single ethanol exposure on HIV replication in human lymphocytes. J Invest Med. 1997;45:265–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nair MP, Schwartz SA, Kronfol ZA, et al. Immunoregulatory effects of alcohol on lymphocyte responses to human immunodeficiency virus proteins. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1990;325:221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fong IW, Read S, Wainberg MA, et al. Alcoholism and rapid progression to AIDS after seroconversion. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:337–8. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pol S, Artru P, Thepot V, et al. Improvement of the CD4 cell count after alcohol withdrawal in HIV-positive alcoholic patients. AIDS. 1996;10:1293–4. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199609000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fein G, Biggins CA, MacKay S. Alcohol abuse and HIV infection have additive effects on frontal cortex function as measured by auditory evoked potential P3A latency. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;37:183–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)00119-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grassi MP, Perin C, Clerici F, et al. Neuropsychological performance in HIV-1-infected drug abusers. Acta Neurol Scand. 1993;88:119–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1993.tb04202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyerhoff DJ, MacKay S, Sappey-Marinier D, et al. Effects of chronic alcohol abuse and HIV infection on brain phosphorus metabolites. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:685–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Theall KP, Clark RA, Powell A, et al. Alcohol consumption, ART usage and high-risk sex among women infected with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:205–15. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9159-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coates RA, Farewell VT, Raboud J, et al. Cofactors of progression to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in a cohort of male sexual contacts of men with human immunodeficiency virus disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:717–22. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaslow RA, Blackwelder WC, Ostrow DG, et al. No evidence for a role of alcohol or other psychoactive drugs in accelerating immunodeficiency in HIV-1-positive individuals. A report from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. JAMA. 1989;261:3424–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samet JH, Cheng DM, Libman H, et al. Alcohol consumption and HIV disease progression. J Acq Immun Def Synd. 2007;46:194–9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318142aabb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lackner AA. Pathology of simian immunodeficiency virus induced disease. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1994;188:35–64. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78536-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Letvin NL, King NW. Immunologic and pathologic manifestations of the infection of rhesus monkeys with simian immunodeficiency virus of macaques. J Ac Immun Def Synd. 1990;3:1023–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohri S, Bonhoeffer S, Monard S, et al. Rapid turnover of T lymphocytes in SIV-infected rhesus macaques. Science. 1998;279:1223–1227. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5354.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bagby GJ, Stoltz DA, Zhang P, et al. The effect of chronic binge ethanol consumption on the primary stage of SIV infection in rhesus macaques. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:495–502. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000057947.57330.BE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bagby GJ, Zhang P, Purcell JE, et al. Chronic binge ethanol consumption accelerates progression of simian immunodeficiency virus disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1781–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Molina PE, Lang CH, McNurlan M, et al. Chronic alcohol accentuates simian acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associate wasting. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:138–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00549.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Staprans SI, Dailey PJ, Rosenthal A, et al. Simian immunodeficiency virus disease course is predicted by the extent of virus replication during primary infections. J Virol. 1999;73:4829–39. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.4829-4839.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watson A, Ranchalis J, Travis B, et al. Plasma viremia in macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency virus: plasma viral load early in infection predicts survival. J Virol. 1997;71:284–90. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.284-290.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodriguez I, Martinez M, Staprans S, et al. Increased viral replication in simian immunodeficiency virus/simian-HIV-infected macaques with self-administering model of chronic alcohol consumption. J Acq Immun Def Synd. 2005;39:386–90. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000164517.01293.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poonia B, Nelson S, Bagby GJ, et al. Chronic alcohol consumption results in higher simian immunodeficiency virus replication in mucosally inoculated rhesus macaques. AIDS Res Hum Retrov. 2005;21:863–8. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Purohit V, Bode JC, Bode C, et al. Alcohol, intestinal bacterial growth, intestinal permeability to endotoxin, and medical consequences: summary of a symposium. Alcohol. 2008;42:349–61. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.03.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poonia B, Nelson S, Bagby GJ, et al. Intestinal lymphocyte subsets and turnover are affected by chronic alcohol consumption: Implications for SIV/HIV infection. J Acq Immun Def Synd. 2006;41:537–47. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000209907.43244.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, et al. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat Med. 2006;12:1365–71. doi: 10.1038/nm1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veazey RS, Acierno PM, McEvers KJ, et al. Increased loss of CCR5+ CD45RA− CD4+ T cells in CD8+ lymphocyte-depleted Simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 2008;82:5618–30. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02748-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]