Abstract

Mutations in PKD2 are responsible for approximately 15% of the autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease cases. This gene encodes polycystin-2, a calcium-permeable cation channel whose C-terminal intracytosolic tail (PC2t) plays an important role in its interaction with a number of different proteins. In the present study, we have comprehensively evaluated the macromolecular assembly of PC2t homooligomer using a series of biophysical and biochemical analyses. Our studies, based on a new delimitation of PC2t, have revealed that it is capable of assembling as a homotetramer independently of any other portion of the molecule. Our data support this tetrameric arrangement in the presence and absence of calcium. Molecular dynamics simulations performed with a modified all-atoms structure-based model supported the PC2t tetrameric assembly, as well as how different populations are disposed in solution. The simulations demonstrated, indeed, that the best-scored structures are the ones compatible with a fourfold oligomeric state. These findings clarify the structural properties of PC2t domain and strongly support a homotetramer assembly of PC2.

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is the most common monogenic life-threatening human disease, with a prevalence of 1∶400 to 1∶1,000 (1). Whereas mutations in the PKD1 gene are responsible for approximately 85% of the disease cases, nearly 15% are caused by pathogenic mutations in PKD2 (1). The PKD2 gene encodes polycystin-2 (PC2), a 968-amino acid (aa) membrane protein with six transmembrane helices (TM) and both C- (PC2t) and N-termini intracytosolic (1, 2). PC2 and the membrane protein polycystin-1 (PC1), the PKD1 gene product, are thought to physically interact by their C-termini (3). In recent years, a series of studies have implicated the primary apical cilia in the pathogenesis of polycystic kidney disease. PC2 is a member of the transient receptor potential (TRP) channel superfamily (TRPP2), acting as a nonselective cation channel involved in calcium transport (1, 4, 5). The PC1–PC2 complex plays a key role in this ciliary mechanism, by apparently translating physical or chemical stimuli in calcium influx through PC2, a process that is followed by significant calcium release from intracellular stores (6).

The PC2 topology predicts the pore structure to reside in TMs 5 and 6, whereas a sensor portion is expected in TMs 1–4 (2, 7). TRP channels have been shown to form homo and/or heteromultimers, a property apparently correlated with quantitative and qualitative aspects of their function (8). Full-length PC2 appears to follow this pattern, because a recent study supports PC2 assembling as a homotetramer and as a PC2-TRPC1 heterotetramer (7). Previous work has suggested that a coiled-coil subdomain identified in the PC2t (PC2t-CC) plays critical roles in PC2 oligomerization and in its physical interaction with PC1 to form the PC1–PC2 complex, a process that also involves a coiled-coil subdomain in PC1t (1). Another recent study, however, suggests that the PC2t-CC assembles as a homotrimer (9). A Ca++-binding EF-hand subdomain has also been predicted in PC2t and been proposed to function as a Ca++-sensing switch (2, 10), whereas the PC2 channel activity has been shown to be regulated by calcium (4, 5, 11).

In spite of the aforementioned information and insights, the macromolecular assembly of PC2t homooligomer continued to be an open question. In the current work, we present the most comprehensive set of analyses yet performed and that show PC2t forms a homotetrameric oligomer. We have proposed a PC2 C-terminal domain delimitation and submitted it to a range of biochemical and biophysical evaluations, including chemical cross-linking, dynamic light scattering (DLS), circular dichroism (CD) and small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) analyses. We have also used molecular dynamics simulations employing an all-atom structure-based model (SBM) to evaluate the macromolecular assembly of PC2t, by comparing the structures obtained from the simulation including the raw SAXS data and by reconstructing the distribution of states in solution using a system forced by entropy. The simulations determined, in fact, that the best-scored structures are also the ones compatible with tetramerization.

Results

In Silico Analysis of PC2t Molecular Properties.

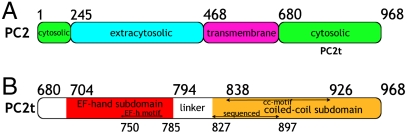

The domain topology of PC2 was initially examined upon the analysis of its primary sequence (Fig. 1). In silico analysis of PC2t polypeptide sequence revealed an inverse correlation between hydrophobicity and tendency of disorder, with significantly low hydrophobicity and high tendency of disorder in the transition between the transmembrane and intracellular domains, aa 649–681 (Fig. S1). A similar pattern was observed for flexibility, particularly for the interface residues between these two domains, where the residues are highly hydrophobic and structurally organized (Fig. S2). The PC2t middle region (aa 800–830) shows remarkably high average flexibility and tendency of disorder, where a linker is positioned between the EF-hand and the coiled-coil subdomains. The same behavior was detected in the PC2t final region (aa 940–968). These results, therefore, support the assignment of the intracytoplasmic PC2t domain to the 289 C-terminal residues 680–968. It must be noted that PC2t is highly charged, with a number of negatively charged residues yielding theoretical pI of 5.1 and molecular mass of 32.6 kDa.

Fig. 1.

(A) Topology of the PC2 predicted domains: in green, the cytosolic domains; in cyan, the putative extracellular domain; and in magenta, the transmembrane domain. (B) Topology of PC2t subdomains and motifs as predicted by PRODOM: in red, EF-hand subdomain and its motif (arrow); and in yellow, the coiled-coil subdomain and its motif and the MS sequenced residues (arrow).

Dynamic Light Scattering.

To access the monodispersity of PC2t samples and for a rough estimation of its maximum dimension, we performed DLS experiments. Such experiments revealed the PC2t samples in the monodispersed state. The estimation of the oligomer maximum dimension was 17 ± 4 nm.

PC2t Expression, Purification, and Molecular Mass Estimation.

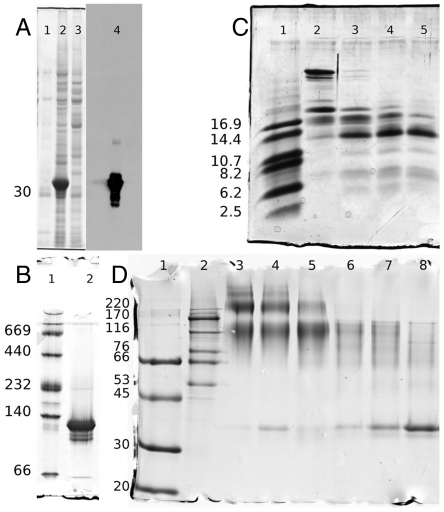

The coding sequence corresponding to PC2t was amplified by standard PCR and cloned in an expression vector. Successful PC2t overexpression followed by western blot analysis of the soluble fraction of cell lysate are shown in Fig. 2A, confirming a band immediately above the 30-kDa marker.

Fig. 2.

(A) PC2t expression is confirmed by immunoblotting with antihistag (Sigma–Aldrich H1029): lane 1, MM standard markers; lanes 2 and 3, respectively, soluble and insoluble fractions of overexpressed PC2t; and lane 4, positive western blotting showing PC2t immediately above the 30-kDa MM marker in crude extract. (B) PC2t N-PAGE: lane 1, MM standard markers; and lane 2, PC2t oligomer immediately bellow the 140-kDa MM marker. (C) Controlled proteolysis of PC2t with trypsin: lane 1, MM markers; lanes 2 to 5, PC2t samples treated with 1∶250 protease:protein mass ratio at 4 °C for 5, 15, 30, and 60 min, respectively. The PC2t structural core is observed at the same height as the 14.4-kDa MM marker. (D) Chemical cross-linking of PC2t samples: lanes 1 and 2, MM markers; lanes 3 to 5, treated with EGS 1 mM for 60, 40, and 20 min of incubation, respectively; lanes 6 to 8, EGS 0.5 mM for 60, 40, and 20 min of incubation.

The PC2t molecular mass (MM) estimation from size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) revealed an apparent mass of 354 kDa, a mass consistent with an oligomer of order 11 (Fig. S3). The PC2t MM estimated by native gel electrophoresis (N-PAGE; Fig. 2B), on the other hand, was 137 kDa, a value consistent with a tetrameric arrangement (Fig. S4). The presence of calcium neither significantly altered PC2t retention time obtained in SEC experiments nor in the migration pattern observed in N-PAGE analyses.

PC2t Chemical Cross-Linking.

To further examine the PC2t homooligomerization assembly, we extended the experimental approach to chemical cross-linking assays, shown in Fig. 2D. A blurred band corresponding to the PC2t oligomer was detected, with a middle-position height slightly above the 116-kDa marker. The profile of the log(MM) vs. Rf plot is sigmoidal, so the assumption of linearity is valid only for a finite but useful range (Fig. S5). Because the nonlinearity is even more pronounced for the higher MM markers, a polynomial regression was applied. The apparent mass calculated for the cross-linked sample was 123 kDa, a mass compatible with a tetramer, whereas a value of 36 kDa was obtained for the negative control sample in accordance to that expected for a monomer.

Structural Features of PC2t Monomer Revealed by Mass Spectroscopy.

Fig. 2C shows the PC2t controlled proteolysis with trypsin, revealing a structural core of approximately 14.4 kDa insensitive to such a proteolytic effect. This finding is, in fact, inconsistent with the in silico trypsinization pattern obtained for PC2t primary sequence, which predicts 40 restriction sites leading to peptides with masses ranging from 147.1 Da (a lysine) to 2845.4 Da (27 residues). The observed data require residues organized in a tridimensional molecular folding, making the remaining arginine and lysine restriction sites not accessible to trypsin activity. Interestingly, the presence of this molecular core was not originally expected, given the intrinsically disorder probability of the primary sequence.

Mass spectroscopy analysis determined the sequence of two peptides resulting from the PC2t macromolecular core. Table S1 displays the matching between the experimental ionic masses and those predicted by in silico trypsinization. As the peptide sequences were univocally determined and the chain is unique, it was possible to conclude that the primary sequence of the molecular core has at least 71 residues, comprising aa 827–897. This region includes the beginning of the PC2t coiled-coil subdomain and corresponds to 8.1 kDa of the molecular core mass. Because the complete sequence of the molecular core could not be established, its remaining portion(s) might theoretically flank either or both sides of the sequenced fragment.

Circular Dichroism Analysis of PC2t.

The far-UV PC2t spectra evaluation supports a calcium-sensitive structural organization at the secondary level (Fig. S6). The PC2t circular dichroism spectrum shows double ellipticity minima at 208 and 222 nm and a maximum ellipticity at 198 nm, findings consistent with an α-helical configuration. The 208-nm minimum is deeper than that of the 222-nm and slightly shifted to a smaller wavelength due to the presence of disordered residues. Complete calcium depletion in the solution, in turn, decreased the ellipticity at 222-nm and 208-nm minima, and decreased its maximum at 198 nm. The 208-nm minimum, moreover, was further displaced to 206 nm, supporting an increase of disordered residues.

Deconvolution of the PC2t spectrum in presence of calcium showed secondary structure contends of 68% of helices, 10% of strands, 10% of turns, and 12% of disordered residues. The complete removal of calcium, on the other hand, led to secondary structure contends of 56% of helices, 17% of strands, 8% of turns, and 18% of disordered residues.

SAXS Solution Analyses of PC2t.

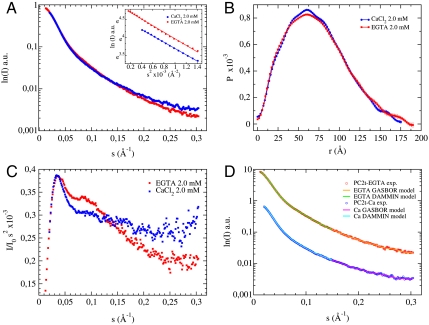

The PC2t particle envelope was assessed by SAXS data solution analyses. Fig. 3A displays the SAXS curves of PC2t in presence of 2.0 mM CaCl2 (PC2t-Ca) and 2.0 mM EGTA (PC2t-EGTA). These results revealed PC2t-Ca and PC2t-EGTA apparent masses of 129 kDa and 139 kDa, respectively. Guinier analyses showed that the PC2t samples were diluted and monodispersed in both conditions, as demonstrated by the linearity of the curves at very low angles. The observation that both linear extrapolations are virtually parallel, in turn, indicates that the PC2t Guinier radii are very close: 52 ± 2 Å in the presence and 54 ± 1 Å in the absence of calcium. In the reciprocal space, both curves superimpose very well in the low angle regimen. Such superimposition, however, is not observed for wider angles in the second and third sectors of the scattering curves (Fig. 3A). Those differences are better appreciated in the real space by comparing their respective distance distribution functions between electron density pairs [P(r)], generated by the indirect Fourier transform of the scattering curves with the GNOM program (12, 13). The PC2t P(r) functions in the presence and absence of calcium are shown in Fig. 3B, revealing distance distributions slightly differ. In presence of calcium, PC2t presents a narrower P(r), centered in a smaller gyration radius (Rg) as a consequence of a smaller maximum dimension (Dmax). In contrast, the absence of calcium suppresses the typical P(r) multidomain shoulders and oscillations corresponding to intra- and intersubunit distances, and Rg and Dmax swell toward a wider distribution of distances. The expansions of Rg and Dmax determined by calcium removal were from 55.9 ± 0.5 Å and 175 Å to 56.8 ± 0.6 Å and 188 Å, respectively. Calcium-induced differences in the PC2t scattering intensities were also detected by the Kratky plot (Fig. 3C). The PC2t-Ca Kratky plot presents a narrow maximum at low-resolution range and a more dispersive profile for higher angles. Calcium removal, in turn, slightly shifted the low-resolution maximum to lower s, indicating that the Rg value is larger than the one obtained in the presence of calcium. In addition, some organization was gained for wider angles. These findings suggest a PC2t multidomain arrangement whose flexibility is modulated or altered upon calcium binding.

Fig. 3.

(A) PC2t small angle X-ray scattering intensities measured at D11A-LNLS in the presence of 2.0 mM CaCl2 or 2.0 mM EGTA and their corresponding Guinier extrapolations (inside); (B) the distance distribution functions between electron density pairs for PC2t in both conditions; (C) the respective Kratky plots; and (D) superimposition between the theoretical and experimental scattering curves from different reconstruction models. The curves were arbitrarily displaced on the vertical axis for clarity.

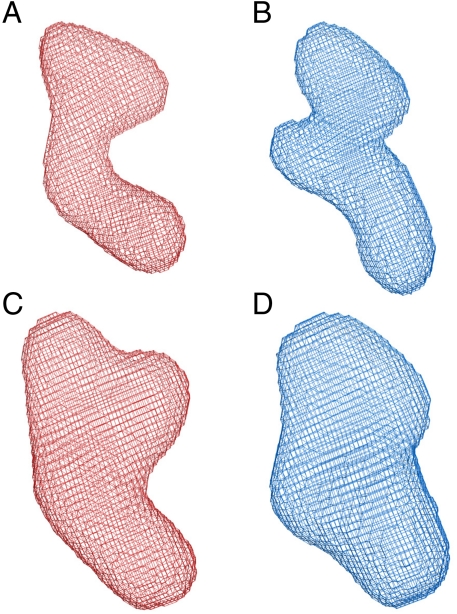

The low-resolution particle shapes of PC2t-Ca and PC2t-EGTA homomultimers were restored from the scattering intensities using two ab initio procedures. The particle envelopes were primarily calculated for low-resolution data (smax = 0.15 Å-1) with the simulated annealing protocol implemented in the DAMMIN program (14). No symmetry was applied because higher order restraints neither improve the χ2 fit between the theoretical and experimental scattering profiles, nor stabilized the normalized standard discrepancies (NSD) among several independent reconstructions. Thirty independent simulations for the calcium and EGTA sets were filtered and averaged with the DAMAVER program (15). All of the ab initio models obtained from SAXS data yielded similar physical parameters. In the second ab initio method, the entire sets of the scattering data were employed in an attempt to identify the PC2t structural subdomains. The uniqueness of the shape restorations was also verified by comparing the NSDs of the superimposing solutions. Cluster analyses based on overall folding, followed by selection of the closest model to the centroid of the largest clusters, were applied to identify a more representative ensemble of conformers. One hundred independent reconstructions were also performed for each calcium and EGTA dataset using the entire resolution range with the program GASBOR (16). The calcium restorations were clustered in four groups, whereas the EGTA set was clustered in nine groups (the isolated clusters were discarded). The superimposition of the theoretical and experimental scattering curves is shown in Fig. 3D. The comparison between the PC2t models from both restoration methods are represented in Table 1, whereas the SAXS models from both reconstruction methods are presented in Fig. 4.

Table 1.

Average structural parameters of the dummy residue models (DRM) from both restoration methods

| DAMMIN | GASBOR | |||

| PC2t-Ca | PC2t-EGTA | PC2t-Ca | PC2t-EGTA | |

| Mass (kDa) | 129.0 (1.1%) | 139.2 (6.7%) | ||

| Dmax (Å) | 175 | 188 | 175 | 188 |

| Rg (Å) | 55.2 | 56.2 | 55.8 | 56.5 |

| V (nm3) | 3,899 | 4,201 | 44.9 | 44.9 |

| Number of dummy residues | 5,594 | 5,642 | 1,156 | 1,156 |

| Free parameters* | 8,306 | 8,590 | 17.13 | 17.52 |

| Discrepancy χ | 0.70 | 0.45 | 1.75 | 1.38 |

| Resolution† | 42.1 | 42.1 | 20.1 | 20.1 |

These data include DAMMIN and GASBOR output parameters for PC2t in the presence and the absence of calcium. The protein molecular mass was obtained using SAXSMOW.

*Number of Shannon channels is given by Ns = Dmax(smax - smin)π-1.

†R = 2π/smax.

Fig. 4.

Final averaged PC2t SAXS envelopes. GASBOR reconstructions for (A) PC2t-EGTA and (B) PC2t-Ca complete datasets; and DAMMIM reconstructions for (C) PC2t-EGTA and (D) PC2t-Ca low-resolution data. (Models in blue are Ca and in red are EGTA; all models are presented in the same orientation).

Tridimensional Structure Simulation and Analysis of PC2t Homooligomer.

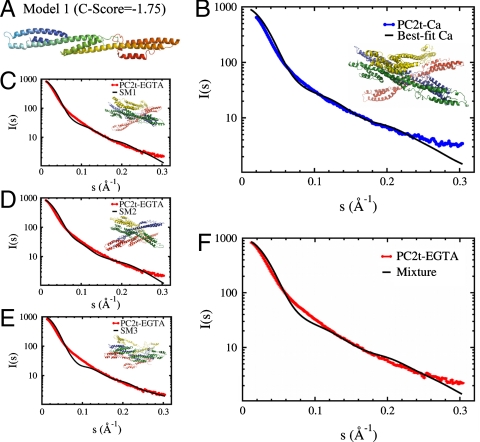

The I-TASSER C-Score function was employed to predict models based on alignments and convergence of structural assemblies (17). Despite their limitations, these models are sufficient to investigate the main features of the protein assembly. Three of the best-scored models (Fig. S7) were chosen to simulate the trimer, tetramer, and pentamer arrangements (Fig. 5). Only the lowest score configuration is in satisfactory agreement with the SAXS data. The computational approaches are described in SI Appendix. Twelve simulations of each possible trimer, tetramer, and pentamer arrangements were performed using a modified version of the all-atoms SBM (18, 19), with different constraints from minimal to maximal monomer separation. The assemblies obtained were compared to the experimental SAXS data using CRYSOL (20). The best fit model for all simulations was achieved for a PC2t tetrameric arrangement in both calcium and EGTA conditions. Fig. 5B shows the superimposition between the best fit model and the PC2t-Ca experimental data (χ = 11.4 and Rg = 51.8 Å), whereas Fig. 5 C–E display the superimposition between the corresponding model and the PC2t-EGTA experimental data (χ = 7.5 and Rg = 53.8 Å). Simulations allowing increased degrees of deformation have not improved the χ values.

Fig. 5.

(A) Monomeric molecular model of PC2t predicted by I-TASSER. Five different predictions were made but only this configuration is in satisfactory agreement with the SAXS data. (B) Superimposition between the PC2t-Ca experimental data (blue) and the theoretical scattering curve from the simulated model SM1-Ca (black). (C), (D), and (E) Superimposition between the PC2t-EGTA experimental data (red) and the theoretical scattering curve, respectively, for the tetrameric simulated models SM1-EGTA, SM2-EGTA, and SM3-EGTA (black). SM1-EGTA shows a good fit in the very low angle region, SM2-EGTA shows a better fit in the middle angle region and SM3-EGTA shows a better fit in the higher angle region (all of them indicated by arrows). (F) Superimposition between the PC2t-EGTA scattering data and the theoretical scattering curve as a combination of the models presented in (C), (D), and (E).

An optimized combination of the best simulated models (SM) enhanced the agreement between the theoretical and experimental data for the EGTA condition. The combination of 70% of the SM1 model (χ = 7.5 and Rg = 53.8 Å), 20% of SM2 (χ = 8.4 and Rg = 53.5 Å), and 10% of SM3 (χ = 8.6, Rg = 54.0 Å) yielded a combined χ of 7.1. Combinations of the calcium-simulated models, on the other hand, have not improved the agreement between theoretical and experimental data in comparison to results obtained with individual models.

Discussion

In addition to a coiled-coil subdomain, the PC2 C-terminal intracytosolic domain includes an EF-hand subdomain and a flexible linker (10), structural features consistent with our results. This C-tail is highly relevant to the protein biology, interacting with a number of binding partners (17). In the current study, in silico analyses based on flexibility, hydrophobicity and tendency of disorder have allowed a suitable delimitation of the polycystin-2 C-terminal cytosolic domain. After a series of procedural adjustments, an appropriate level of soluble expression of the entire PC2t was achieved. Construct nucleotide sequencing, positive immunochemical assays and mass spectroscopy-based peptide sequencing of proteolysis-derived products ensured the accuracy of each step.

The PC2t apparent mass obtained from size-exclusion chromatography was in disagreement with the results yielded by the other methods. It must be noted, however, that these SEC results were interpreted as a large deviation of the PC2t oligomer from globularity. This conclusion was corroborated by the maximum dimension derived from DLS and SAXS analyses. N-PAGE results, moreover, revealed an apparent mass highly agreeable with the value derived from its aminoacid sequence for four identical subunits (relative error of 5%). Charge effects were not observed, because the PC2t pI and the running pH were sufficiently close. The tetrameric hypothesis was also supported by the mass estimation of PC2t oligomer resulting from the chemical cross-link analysis (relative error of 6%). A second band of higher MM was also observed when using higher EGS concentrations. The experiment shows, indeed, that this band is an EGS concentration and time artifact, because it is absent in the set of experiments run under lower EGS concentration. This explanation is particularly strengthened considering the EGS concentration range (50-fold excess).

A third independent set of results supports a tetrameric organization for PC2t. The SAXS MM estimation, performed in solution, revealed a high level of agreement between the PC2t determined mass and the mass expected for a tetrameric arrangement, both in the presence and in the absence of calcium (relative errors of 1% and 7%, respectively). The PC2t MM difference observed in our analysis was in fact expected because different volumes were found in the two conditions but the MM estimation was calculated using the same density, 1.37 g cm-3 (18). The three outlined sets of data, therefore, lead to a proposed model of tetrameric assembly for PC2t. This model is supported by data from Zhang et al., based on work with the full-length product and multimer assembly evaluation with atomic force microscopy, followed by consistent functional results (7). Notably, the homotetrameric arrangement is also observed in other members of the TRP cation channel superfamily, including the Ca++-permeable channels TRPV6 (19) and TRPC1 (20). A recent study proposes a tetrameric assembly of PC2 including the C- and N-terminal dimerization domains (21). Our data, however, have demonstrated that the homotetrameric assembly can occur independently of PC2 N-terminus. This is a key structural point, showing that the C-tail itself is capable of directing assembly of PC2.

In the initial stages of refining the purification protocol, we observed a coexisting lower band in some of our N-PAGE experiments that appeared to be related to the assembly of noncanonical thrombin cleavage products. Whereas we cannot exclude the possibility that this band is a homotrimeric form of PC2t, it would be formed in very minor quantities under specific physicochemical conditions, coexisting with far predominating homotetramers.

The PC2t oligomerization state may have become a controversial issue due to interpretation of data based on incomplete PC2 C-terminal delimitation. Although a functional PC2 trimeric channel has not been reported to present, recent studies are compatible with this hypothetical arrangement (9, 22). These analyses, however, were performed with incomplete PC2ts. Our proposed PC2t delimitation, in turn, shows that the full-length PC2 cytoplasmic domain encompasses regions that are necessary and sufficient for the homotetramer formation that are absent in PC2t segments previously evaluated.

Our MS results are consistent with a PC2t multiflexible-domain organization. Controlled proteolysis showed that at least 71 aa, residues 827–897, are folded in a tridimensional arrangement. Most of the 40 restriction sites were found exposed to trypsin activity, suggesting sequence flexibility and/or partial unfolding. This structural concept is supported by the CD analyses, which showed an increasing number of disordered residues in the absence of calcium. This effect was also observed for wider angles in the PC2t Kratky analysis.

The PC2t N-PAGE, DLS, and the Guinier analyses for calcium and EGTA conditions indicate that the SAXS experiments were conducted with homogeneous and monodispersed samples, validating the subsequent data treatment. The experimental P(r) profiles, Dmax and Rg from samples in the presence and absence of calcium suggest that the PC2 intracellular domain adopts a multilobular prolate arrangement. In addition, the Kratky plot analysis revealed an interesting mechanism of calcium-induced conformational change. Both independent ab initio reconstructions for PC2t-Ca and for PC2t-EGTA molecular envelopes yielded very consistent results (Table 1). The data maximum resolution did not allow determination of the spatial positions of their secondary structure elements, but allowed the obtainment of the overall PC2t shapes in the presence and the absence of calcium. These data provide important insights into the relative position of their subdomains. It should be emphasized that the PC2t P(r) observations in both conditions were translated into their respective molecular envelopes. As made clear in Fig. 4, PC2t presents a multilobular prolate shape, a feature even more pronounced for the wider-angle reconstructions. The calcium-induced conformational modifications can be also observed when comparing the PC2t molecular envelopes associated with the presence and the absence of this cation. The analysis of wider-angle reconstructions revealed a lower number of clusters for the PC2t-Ca condition, suggesting a more rigid packing as outlined by the Kratky analysis. Our data suggest that the slender portion of the PC2t-EGTA wider-angle molecular envelopes includes the coiled-coil subdomain and the bulk part of the model encompasses the EF-hand subdomain, whereas the final flexible region of PC2t remains to be determined. Higher resolution techniques, however, have to be applied to confirm this arrangement.

A single rigid structure is expected to bring limited information from a SAXS analysis. Better adjustments were obtained for the PC2t-EGTA data when appropriate mixtures of simulated models were applied. The combination of three simulated models at different ratios yielded the same χ value whereas providing information on the flexibility of the system. This approach, however, can be employed to obtain details on the geometrical nature of the oligomerization interface. Structure-based simulations have energy functions based on the predicted structures. In both cases, however, our simulation results are in accordance with the experimental findings, supporting our proposed PC2t homotetrameric arrangement. The comparison of theoretical profiles and experimental SAXS data demonstrated that the trimeric or pentameric arrangements are inconsistent (see details in SI Appendix).

Mixing multiple structures does not substantially improve the PC2t analysis, indicating further assembly rigidity and therefore higher organization. This supports the notion that calcium increases the assembly stability. This region also provides information about the monomer extension and compactness of the assembly. The intermediate s region shows the presence of multiple conformations. By simply mixing three representative structures, a better theoretical adjustment to the experimental data is obtained. The large s region shows the existence of dynamical fluctuations varying from local ones all the way up to assembly compactness. Our dynamic oligomerization hypothesis was also supported by the SAXS data solution, using a recently developed approach (23–25). The applied molecular dynamics strategy was proposed for protein quaternary structure elucidation, particularly to such a flexible and complex system, and should be useful for other systems. Our results, in fact, are in accordance with all experimental analyses. The homotetrameric molecular model for PC2t should serve as a starting point to focus on questions directed to the PC2 channel architecture, gating mechanism and roles in ADPKD.

Methods

Computational Analysis.

Analysis of PC2t primary sequence allowed the identification of the membrane interface residues and its intracytosolic domain. We were able to exclude the last TM residues without removing aminoacids potentially important for folding by quantifying hydrophobicity (26), mean flexibility (27) and tendency of disorder (28). The MARCOIL program (29) was used for coiled-coil prediction and PRODOM (30) for scanning known structural motifs and subdomains.

Cloning, Expression, Purification, and Dynamic Light Scattering.

Specific primers were designed for unidirectional cloning of the PKD2 nucleotide segment corresponding to PC2t. Several plasmids and cell lines were tested to define the appropriate insert-vector system (31). PC2t was purified from cell lysate using immobilized affinity chromatography, following a size-exclusion chromatography step.

The monodispersity of the PC2t samples and the maximum dimension of the oligomer was estimated using the right angle dynamic light scattering analyzer Zetasizer μV (Malvern Instruments). PC2t samples of 60 μM were analyzed at 10 °C in the same conditions adopted in the SAXS experiments.

Estimation of PC2t Molecular Mass and Chemical Cross-linking.

The PC2t homomultimer MM was estimated by native gel electrophoresis performed in a polyacrylamide gradient of 10% to 15% (M/V), 112 mM acetate and 112 mM Tris at pH 6.4, using the PhastSystem (GE Healthcare). PC2t MM was derived from the linear regression of the log(MM) vs. Rf (retardation factor) plot. An additional estimation of PC2t MM was obtained using size-exclusion chromatography on a Superdex200-10/300 column (GE Healthcare). PC2t MM was estimated from linear regression of the log(MM) vs.  plot, where

plot, where  is the gel-phase distribution coefficient.

is the gel-phase distribution coefficient.

For chemical cross-linking analyses, 20-μM PC2t samples in PBS were incubated in the presence of EGS to the final concentrations of 0.5 mM and 1.0 mM. The MM of the PC2t cross-linked samples were calculated from the polynomial regression of the log(MM) vs. Rf plot.

Mass Spectroscopy.

Controlled trypsinization was carried out at several protease:protein molar ratios, temperatures and incubation times. Products of interest yielded by proteolysis were purified by electrophoresis on 16% tricine gels, excised and submitted to an additional proteolytic process. The MS evaluation of the resulting peptides was carried out with a quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer micrOTOF-QII (Bruker), in the direct injection mode. The quantified ionic masses were compared to primary sequence databases using the search engine MASCOT (32).

Circular Dichroism.

The PC2t circular dichroism spectra were assessed by far-UV CD spectroscopy using a J-815 Jasco spectropolarimeter equipped with a Peltier temperature control unit. The CD spectra represented the average of 20 accumulations, using a scanning speed of 50 nm/ min, a spectral bandwidth of 0.5 nm, and a response time of 1 s. PC2t samples of 1 to 2.5 μM were measured in 10 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol in 5 mM Tris, pH 7.0, and 2.0 mM CaCl2 or EGTA. The CD spectra deconvolution was performed with the program CDSSTR (33) using the reference database SP175 (34).

SAXS Data Collection and Processing.

Small angle X-ray scattering data were collected at the D11A-SAXS beamline (35) in the Brazilian Synchrotron Light Laboratory electron storage ring. Scattering data covering momentum transfers between 0.01 Å-1 < s < 0.3 Å-1* were recorded with a MAR145 image plate detector (Marresearch), using the 1.1488 Å wavelength, sample-detector distance of 1290.98 mm and samples from 3 to 8 mg mL-1. The sample and buffer scattering image intensities were normalized to the intensity of the incident beam for fluctuation correction and subtracted, following the integration with the FIT2D program (36). The scattering data were processed and normalized against the forward scattering intensity. The PC2t MM, in turn, was determined by the SAXSMOW program (37).

Tridimensional Structure Prediction.

A simulation approach was used to characterize the complex PC2t tridimensional arrangement. In the current work, molecular dynamics and SAXS were combined as sources of information. Automated molecular modeling was also applied for PC2t monomer folding using the online I-TASSER server 3D protein predictor (38).

Conformational Searching Employing Structure-Based Models.

SBM simulations have been very successful in understanding functional and folding aspects of protein complexes (23, 39–43), including interpretation of SAXS data for protein complexes (24). In this study, we have added additional terms to the SBM energy function (described in detail in SI Appendix) to provide us the freedom to adjust the theoretical model to the appropriate protein monomer elongation and the degree of compactness of the full complex.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Glaucius Oliva for financial support [Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) INCT-INBEQMeDI] and access to his laboratory. We thank Hannes Fischer for valuable discussion and manuscript revision; Andressa P. A. Pinto for excellent technical support; and Paul C. Whitford for helpful suggestions on modeling. This work was mainly supported by Brazilian agency Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) Grant 2006/03098-8 (F.M.F. and L.F.O.) and LIMs of University of São Paulo School of Medicine. Additional support was provided by The Johns Hopkins Polycystic Kidney Disease (PKD) Research and Clinical Core Center [National Institutes of Health (NIH) P30 DK090868]. L.C.O. was partially supported by CNPq. Work in San Diego was supported in part by the Center for Theoretical Biological Physics sponsored by the National Science Foundation (NSF) Grant PHY-0822283 and NSF Grant MCB-1051438.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1106766108/-/DCSupplemental.

*The scattering vector s = 4 sin(θ)λ-1, where 2θ is the scattering angle. All envelops and molecules were drawn using PyMOL (www.pymol.sourceforge.net).

References

- 1.Torres VE, Harris PC. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: The last 3 years. Kidney Int. 2009;76:149–168. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mochizuki T, et al. PKD2, a gene for polycystic kidney disease that encodes an integral membrane protein. Science. 1996;272:1339–1342. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5266.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qian F, et al. PKD1 interacts with PKD2 through a probable coiled-coil domain. Nat Genet. 1997;16:179–183. doi: 10.1038/ng0697-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.González-Perrett S, et al. Polycystin-2, the protein mutated in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), is a Ca2+-permeable nonselective cation channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1182–1187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vassilev PM, et al. Polycystin-2 is a novel cation channel implicated in defective intracellular Ca(2+) homeostasis in polycystic kidney disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:341–350. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou J. Polycystins and primary cilia: primers for cell cycle progression. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009;71:83–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang P, et al. The multimeric structure of polycystin-2 (TRPP2): Structural-functional correlates of homo- and hetero-multimers with TRPC1. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:1238–1251. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catterall WA. Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:521–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu Y, et al. Structural and molecular basis of the assembly of the TRPP2/PKD1 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11558–11563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903684106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ćelić A, Petri ET, Demeler B, Ehrlich BE, Boggon TJ. Domain mapping of the polycystin-2 C-terminal tail using de novo molecular modeling and biophysical analysis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:28305–28312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802743200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koulen P, et al. Polycystin-2 is an intracellular calcium release channel. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:191–197. doi: 10.1038/ncb754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Svergun DI, Semenyuk AV, Feigin LA. Small-angle-scattering-data treatment by the regularization method. Acta Crystallogr A. 1988;44:244–250. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Svergun DI. Determination of the regularization parameter in indirect-transform methods using perceptual criteria. J Appl Crystallogr. 1992;25:495–503. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Svergun DI. Restoring low resolution structure of biological macromolecules from solution scattering using simulated annealing. Biophys J. 1999;76:2879–2886. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77443-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volkov VV, Svergun DI. Uniqueness of ab initio shape determination in small-angle scattering. J Appl Crystallogr. 2003;36:860–864. doi: 10.1107/S0021889809000338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Svergun DI, Petoukhov MV, Koch MH. Determination of domain structure of proteins from X-ray solution scattering. Biophys J. 2001;80:2946–2953. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76260-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Witzgall R. TRPP2 channel regulation. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2007;179:363–375. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-34891-7_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer H, Polikarpov I, Craievich AF. Average protein density is a molecular-weight-dependent function. Protein Sci. 2004;13:2825–2828. doi: 10.1110/ps.04688204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoenderop JGJ, et al. Homo- and heterotetrameric architecture of the epithelial Ca2+ channels TRPV5 and TRPV6. EMBO J. 2003;22:776–785. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barrera NP, et al. AFM imaging reveals the tetrameric structure of the TRPC1 channel. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;358:1086–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng S, et al. Identification and functional characterization of an N-terminal oligomerization domain for polycystin-2. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:28471–28479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803834200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molland KL, Narayanan A, Burgner JW, Yernool DA. Identification of the structural motif responsible for trimeric assembly of the C-terminal regulatory domains of polycystin channels PKD2L1 and PKD2. Biochem J. 2010;429:171–83. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim SJ, Dumont C, Gruebele M. Simulation-based fitting of protein–protein interaction potentials to SAXS experiments. Biophys J. 2008;94:4924–4931. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.123240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang S, Park S, Makowski L, Roux B. A rapid coarse residue-based computational method for X-ray solution scattering characterization of protein folds and multiple conformational states of large protein complexes. Biophys J. 2009;96:4449–4463. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jamros MA, et al. Proteins at work: a combined small angle X-RAY scattering and theoretical determination of the multiple structures involved on the protein kinase functional landscape. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:36121–36128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.116947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kyte J, Doolittle RF. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhaskaran R, Ponnuswamy PK. Positional flexibilities of amino acid residues in globular proteins. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1988;32:241–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1984.tb00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dosztányi Z, Csizmók V, Tompa P, Simon I. The pairwise energy content estimated from amino acid composition discriminates between folded and intrinsically unstructured proteins. J Mol Biol. 2005;347:827–839. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delorenzi M, Speed T. An HMM model for coiled-coil domains and a comparison with PSSM-based predictions. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:617–625. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.4.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Servant F, et al. ProDom: Automated clustering of homologous domains. Brief Bioinform. 2002;3:246–251. doi: 10.1093/bib/3.3.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berrow NS, et al. Recombinant protein expression and solubility screening in Escherichia coli: A comparative study. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:1218–1226. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906031337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perkins DN, Pappin DJ, Creasy DM, Cottrell JS. Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence databases using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:3551–3567. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991201)20:18<3551::AID-ELPS3551>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sreerama N, Woody RW. Estimation of protein secondary structure from circular dichroism spectra: Comparison of CONTIN, SELCON, and CDSSTR methods with an expanded reference set. Anal Biochem. 2000;287:252–260. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitmore L, Wallace BA. Protein secondary structure analyses from circular dichroism spectroscopy: Methods and reference databases. Biopolymers. 2008;89:392–400. doi: 10.1002/bip.20853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kellermann G, et al. The small-angle X-ray scattering beamline of the Brazilian synchrotron light laboratory. J Appl Crystallogr. 1997;30:880–883. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hammersley AP, Svensson SO, Hanfland M, Fitch AN, Hausermann D. Two-dimensional detector software: From real detector to idealised image or two-theta scan. High Pressure Res. 1996;14:235–248. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fischer H, Oliveira Neto M de, Napolitano HB, Polikarpov I, Craievich AF. Determination of the molecular weight of proteins in solution from a single small-angle X-ray scattering measurement on a relative scale. J Appl Crystallogr. 2010;43:101–109. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y. I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:40–48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noel JK, Whitford PC, Sanbonmatsu KY, Onuchic JN. SMOG@ctbp: Simplified deploymnet of structure-based models in GROMACS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W657–W661. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oliveira LC, Schug A, Onuchic JN. Geometrical features of the protein folding mechanism are a robust property of the energy landscape: a detailed investigation of several reduced models. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:6131–6136. doi: 10.1021/jp0769835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whitford PC, et al. An all-atom structure-based potential for proteins: Bridging minimal models with all-atom empirical forcefields. Proteins. 2009;75:430–441. doi: 10.1002/prot.22253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clementi C, Nymeyer H, Onuchic JN. Topological and energetic factors: what determines the structural details of the transition state ensemble and “en-route” intermediates for protein folding? An investigation for small globular proteins. J Mol Biol. 2000;298:937–953. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lammert H, Schug A, Onuchic JN. Robustness and generalization of structure-based models for protein folding and function. Proteins. 2009;77:881–891. doi: 10.1002/prot.22511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.