Abstract

This article uses meta-analysis to develop a model integrating research on relationships between employee perceptions of general and work–family-specific supervisor and organizational support and work–family conflict. Drawing on 115 samples from 85 studies comprising 72,507 employees, we compared the relative influence of 4 types of workplace social support to work–family conflict: perceived organizational support (POS); supervisor support; perceived organizational work–family support, also known as family-supportive organizational perceptions (FSOP); and supervisor work–family support. Results show work–family-specific constructs of supervisor support and organization support are more strongly related to work–family conflict than general supervisor support and organization support, respectively. We then test a mediation model assessing the effects of all measures at once and show positive perceptions of general and work–family-specific supervisor indirectly relate to work–family conflict via organizational work–family support. These results demonstrate that work–family-specific support plays a central role in individuals’ work–family conflict experiences.

An increasingly important area of human resource management (HRM) research involves not only examining formal HR policies but also informal employee perceptions of support at work. For example, although early work–family (W–F) research emphasized how employees’ access and use of formal workplace supports (i.e., work–family policies, such as on site child care) can reduce work–family conflict (e.g., Goff, Mount, & Jamison, 1990; Kossek & Nichol, 1992), in recent years, the field has shifted to emphasize informal workplace support, such as a supervisor sympathetic to work–family issues (Hammer, Kossek, Yragui, Bodner & Hanson, 2009; Thomas & Ganster, 1995) or a positive work–family organizational climate (Allen, 2001).

Many new HRM trends heightening workplace stress have made it critical for personnel psychologists and managers to better understand informal workplace social support linkages to work–family conflict. These include shifting labor market demographics to include more workers that value work–life flexibility such as, parents, millennials, and older workers; rising work hours and workloads distributed on 24–7 operating systems, sharpening the pace and intensity of work; and escalating financial, market and job insecurity from the global economy (Kossek & Distelberg, 2009). Despite the growing importance of understanding workplace social support linkages to work–family conflict due to these rising pressures, research has yet to fully clarify (a) what type of social support (general or work–family specific), either from supervisory or organizational sources, is most strongly related to work–family conflict; and (b) the processes by which these types of support relate to work–family conflict.

In this meta-analysis, we integrate theory from the broader social-support (Caplan, Cobb, French, Harrison, & Pinneau, 1975), perceived-organizational-support (POS; Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison, & Sowa, 1986), and work–family stress literatures (Bakker & Demeroutti, 2007; Hobfoll, 1989) to address these gaps. We develop and test a model of the mediating effects of POS (general and work–family specific) on the relationship between supervisor support (general and work–family specific) and work-to-family conflict. Our study advances findings from previous meta-analyses, which found that relationships between general work support and family and job satisfaction are partially mediated by work–family conflict (Ford, Heinen, & Langkamer, 2007) and that social support is an antecedent of role stressors and ultimately work–family conflict (Michel, Michelson, Pichler, Cullen, 2010). Although these meta-analyses are valuable additions, none examined relationships among all four of the most widely assessed types of workplace social supports and work–family conflict separately or in an integrated path analytic model. By addressing these issues, our research has key implications for the work–family field theoretically (increasing understanding of the nomo-logical net of social support and work–family conflict) and practically (identifying the types of support employers and managers should develop and reinforce).

Workplace Social Support and Work–Family Conflict

Construct Definitions and Linkages

Work–family conflict

Work–family conflict is a form of interrole conflict that occurs when engaging in one role makes it more difficult to engage in another role (Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, Snoek, & Rosenthal, 1964). It is a growing type of stress for most employees in the United States (Aumann & Galinsky, 2009) and internationally (Poelmans, 2005). Work–family conflict is an important antecedent of job and life effectiveness, as many reviews show it is associated with a wide range of positive and negative work-, family-, and stress-related outcomes (Allen, Herst, Bruck, & Sutton, 2000; Eby, Casper, Lockwood, Bordeaux, & Brinley, 2005; Kossek & Ozeki, 1998). Based on theoretical grounding showing that a lack of workplace social support is most likely to impact work-to-family conflict in the direction of the work role interfering with the family role (cf. Frone, Russell, & Cooper, 1992), we focused this meta-analysis on studies measuring relationships between workplace social support and work-to-family conflict.

Workplace social support

The concept of workplace social support is derived from the broader social-support literature. It is typically viewed as a global construct (House, 1981) with a range of definitional dimensions that fluctuate in meaning. One of the most widely used and earliest definitions comes from Cobb (1976), who defined social support as an individuals’ belief that she is loved, valued, and her well-being is cared about as part of a social network of mutual obligation. Others have viewed social support as involving perceptions that one has access to helping relationships of varying quality or strength, which provide resources such as communication of information, emotional empathy, or tangible assistance (Viswesvaran, Sanchez, & Fisher, 1999). Our review suggested that both of these core ideas of (a) feeling cared for and appreciated; and (b) having access to direct or indirect help have been used in the social-support literature, often combined in global measures. Regardless of the items used, we assume that social support is a critical job resource that makes the role demands for which support is given such as the integration of the work–family interface experienced more positively.

Workplace social support is defined as the degree to which individuals perceive that their well-being is valued by workplace sources, such as supervisors and the broader organization in which they are embedded (Eisenberger, Singlhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski, & Rhoades, 2002; Ford et al., 2007), and the perception that these sources provide help to support this well-being. We conceptualize workplace social support as (a) emanating from multiple sources, such as supervisors, coworkers,1 and employing organizations; and (b) distinguished by different types or foci of support that are either “content general” or “content specific.” General work support is the degree to which employees perceive that supervisors or employers care about their global well-being on the job through providing positive social interaction or resources. Content-specific support involves perceptions of care and the provision of resources to reinforce a particular type of role demand. We examine work–family-specific support, the degree to which employees perceive supervisors or employers care about their ability to experience positive work–family relationships and demonstrate this care by providing helpful social interaction and resources. Examples of general and content-specific support are below.

General supervisor support and supervisor work–family support

General supervisor support involves general expressions of concern by the supervisor (i.e., emotional support) or tangible assistance (i.e., instrumental support) that is intended to enhance the well-being of the subordinate (c.f., House, 1981). Whereas general supervisor support focuses on support for personal effectiveness at work, supervisor work–family support facilitates the employee’s ability to jointly manage work and family relationships. Supervisor work–family support is defined as perceptions that one’s supervisor cares about an individual’s work–family well-being, demonstrated by supervisory helping behaviors to resolve work–family conflicts (Hammer et al., 2009) or attitudes such as empathy with one’s desire for work–family balance (Thomas & Ganster, 1995).

Perceived organizational support and organizational work–family support

Organizational support theory holds that individuals personify organizations by attributing human-like characteristics to them and that they develop positive social exchanges with organizations that are supportive (Eisenberger, Armeli, Rexwinkel, Lynch, & Rhoades, 2001). POS (Eisenberger et al., 1986) refers to employees’ overall beliefs regarding the degree to which an employer values employees, cares about their well-being, and supports their socioemotional needs by providing resources to assist with managing a demand or role. POS can also be content specific to a domain such as employees’ family-supportive organizational perceptions (FSOP), the degree to which an organization is seen as family supportive (Allen, 2001). We build on this work and define organizational work–family support as perceptions that one’s employer (a) cares about an employee’s ability to jointly effectively perform work and family roles and (a) facilitates a helpful social environment by providing direct and indirect work–family resources. Examples are a work–family climate (indirect support) where workers feel they do not have to sacrifice effectiveness in the family role to perform their jobs and can share work–family concerns (cf., Kossek, Colquitt, & Noe, 2001), and perceived access to useful work–family policies (direct support). Three hypotheses guide this meta-analysis, which are explained with rationale below.

Hypotheses

Supervisor and organizational support linkages to work–family conflict

When examined separately, we expect that both general and work–family-specific workplace support will have a direct and negative relationship with work-to-family conflict. The rationale for this hypothesis draws on and integrates assumptions from social support (Caplan et al., 1975; House, 1981), and conservation of resources (COR; Hobfoll, 1989) and job demands–resources (JD–R) theories (Karasek, 1979). The primary tenets of COR theory are that individuals strive to gain and maintain resources that are valuable to them and that resource loss has a greater psychological impact than does resource gain as related to stress. A key proposition of the JD–R model is that interactions between job demands and resources are important, such that certain resources (e.g., social support) can mitigate the negative psychological effects (e.g., burnout) of stress.

Because work-to-family conflict is a situation where the demands of the work role deplete resources (e.g., time, energy, emotions) required to participate in the family role (Lappiere & Allen, 2006), individuals with greater access to workplace social support garner additional job psychological resources (cf., Bakker & Demorouti, 2007) that provide a stress buffer to manage strain. When individuals feel socially supported at work, they feel cared for by social others and feel that they have access to help (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Hobfoll, 1989). As individuals perceive more social support, their emotional and psychological supplies for coping with daily stressors increase and perceptual appraisals of stressors decrease (Jex, 1998). When individuals have more social support in general and content specifically for managing work–family issues, these positive dynamics may spillover into the family role thereby reducing work to family conflict (e.g., Frone et al., 1992).

Hypothesis 1: Perceptions of workplace social support both general (perceived organizational support, supervisor support) and work–family-specific (organizational work–family support, supervisor work–family support) will be negatively related to work-to-family conflict.

General versus work–family-specific support linkages to work–family conflict

We expect that work–family-specific support will have a stronger relationship with work-to-family conflict than will general workplace support. The rationale for this proposition is based on the assumption that work–family-specific support is likely to be a more psychologically and functionally useful resource to manage work–family stressors, such as time, strain, or behavior-based conflicts, the main theoretical components of work–family conflict (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985), than general work-place social support.

Work–family research has shown that trying to manage demands from multiple roles (i.e., work and family) leads to reduced resources and increased strain in the form of work-to-family conflict (Grandey & Cropanzano, 1999). Work–family-specific social support goes a step further than general support, in that it not only buffers stress from job demands but helps to conserve resources in both the work and family domains (Allen, 2001) by providing support specifically directed at balancing demands from both spheres (Hammer et al., 2009; Thomas & Ganster, 1995). For example, supervisors providing work–family-specific support will be viewed as caring more about work–family well-being and providing more help to ensure work–family effectiveness than supervisors who are only generally supportive for the work role. As a result, employees with greater access to work–family-specific support will feel they have more work–family-specific psychological resources than those with general support. Employees will be more likely to feel comfortable discussing work–family problems with supervisors perceived as providing a lot of work–family-specific support or asking for greater flexibility or autonomy to better manage the work–family interface. This will enable employees who perceive they have high work–family-specific support to feel in greater control of work–family demands and perceive they have more content-relevant resources to manage work–family conflicts than those who only perceive they have general supervisor support.

Granted, certainly perceiving one has a generally supportive supervisor who cares about one’s overall well-being is a resource. However, theory suggests general support will be less strongly related to work–family conflicts. For example, general support may not necessarily give workers more autonomy over where and when the work role is done to handle work–family demands nor increase employee access to or communication of information on work–family policies or provide a sounding board for openly discussing work–family conflicts (Thomas & Ganster, 1995). Similarly, organizations perceived as providing greater work–family-specific support will be more likely to be seen as valuing employee well-being not only at work but also at home and as having more helpful work–family-specific resources such as work–family policies that can be used without backlash than those providing just general organizational support.

Besides theoretical reasons, construct measurement rationale also supports stronger relationships between work–family conflict and work–family-specific support compared to general workplace support. We draw on a bandwidth fidelity argument from measurement experts arguing that the breadth of the predictor and criterion should be congruent in order to have a stronger correlation or association with each other (Hogan & Holland, 2003). Indeed, a recent validation study found work–family-specific support to be significantly related to lower work–family conflict over and above a general measure of supervisor support (Hammer et al., 2009).

Hypothesis 2: Perceptions of work–family-specific support will be more strongly related to work-to-family conflict than general perceptions of workplace social support. Work–family-specific supervisor support will be more strongly related to work-to-family conflict than will general supervisor support, and FSOP will be more strongly related to work-to-family conflict than will perceived organizational support.

Model of relationships between different support types and sources and work-to-family conflict

No existing research has integrated an examination of the relationships between different types of social support across supervisor and organizational sources as related to work-to-family conflict in a single model. This is a significant omission because, in a simultaneous model, one type (general or work–family specific) or source (organizational or supervisor) of support may become a more or less important predictor of work–family conflict when controlling for other types and sources of support. Although direct relationships in relation to WFC are posited when different types and sources of support are examined separately, when all forms of support are examined simultaneously we expect that POS (general and work–family-specific) will mediate relationships between general and work–family-specific supervisor support and work-to-family conflict.

Toward this end, we develop a mediation model to examine interrelationships between work-to-family conflict and different types of work-place social support (general, and work–family specific) simultaneously. We argue that workplace social support and work–family conflict constructs comprise an important interrelated employee–employer social system. Organizational support theory contends that employee perceptions of supervisor support contribute to perceptions of organizational support (Eisenberger et al., 1986; 2002). Because a supervisor acts as a representative of the organization, assuming a supervisor has respect, (Eisenberger et al., 2002), his/her supportiveness will lead an employee to be more likely to perceive the organization as supportive. Rhoades and Eisenberger (2002) documented that perceptions of organizational support mediate relationships between supervisor support and outcomes relevant to this study such as strain. Further work by Eisenberger et al., (2002) found that supervisor support contributed to temporal change in organizational support (but not vice versa); and POS fully mediated the relationship between supervisor support and turnover. These results suggest that supervisor support is related to POS and that the latter is often a mediator for supervisor support and employee work–family-related outcomes (strain).

Extending this view, Allen (2001) proposed that perceptions of organizational work–family support will mediate relationships between supervisor work–family support and similar work-related outcomes. Indeed, Allen (2001) found that organization work–family support completely mediated the relationship between supervisor support and work–family conflict. Overall, existing theory and research (e.g., Behson, 2002) would suggest that both types of organizational support will mediate the relationships between both types of supervisor support and work–family conflict.

Hypothesis 3: Perceptions of organizational support (general and work–family specific) will mediate the relationships between supervisor support (general and work–family specific) and work-to family conflict.

Method

Inclusion Criteria and Literature Search

We included studies that (a) measured workplace social support, (b) measured work-to-family conflict, and (c) reported sufficient information to compute an effect size. We obtained both published and unpublished studies through four methods. First, we conducted an extensive computerized search of the PsycINFO Business Source Elite, Academic Search Elite, Sociological Abstracts, and the Academy of Management archive databases from their inception, which is as early as 1905 for PsycINFO, through April 2010. We used using the following keywords: supervisor support, organizational support, social support, work and life, work–home, work–family interference, and work–family conflict. Second, we conducted a computerized search of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology’s (SIOP) and the Academy of Management’s meetings online databases, and the Dissertation Abstracts International database for unpublished studies through April 2010 using the same key words. We also did manual searches of journals, such as Personnel Psychology, Journal of Applied Psychology, Academy of Management Journal, Organizational Behavior, and Human Decision Processes, as a check on our computerized search. Finally, we sent out e-mails on discussion lists inviting unpublished work. We also invited authors to send us unpublished studies at the end of a presentation of an earlier version of the paper at a national conference (Society of Industrial Organizational Psychology [SIOP]), in order to increase sample size during writing revisions. This process yielded 115 samples from 85 studies comprising 72,507 employees for inclusion, which are noted in the Appendix.

Study Coding

To establish reliability of coding, two graduate students independently coded the studies. Given our interest in how general and work–family-specific workplace social supports are related to work–family conflict, these individuals independently coded whether measures reflected supervisor or organizational support and whether they were general or specific to the work–family context. Coding was based on scale descriptions and/or sample items provided either in the included studies or in separate published validation studies. Agreement was 100% for the source (supervisor vs. organization) and 95% for the type (general vs. work–family-specific) of support. Disagreements were resolved after discussion.

Meta-Analytic Procedures

Effect-size metric and modeling procedures

The effect-size metric chosen was the correlation coefficient. Our meta-analytic procedures followed conventional model meta-analytic techniques for tests of effect-size centrality and homogeneity (Hedges & Olkin, 1985; Hedges & Vevea, 1998); used random-effects models throughout; and Z-tests for tests of effect-size centrality (cf. Lipsey & Wilson, 2001).

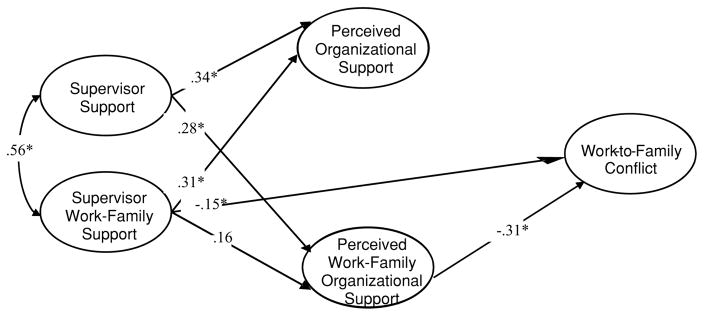

Correlations were transformed into the Fisher correlation metric for analysis. These were then back transformed into the correlation metric. For estimation and testing, we weighted each effect size by the inverse of its sampling variance giving greater weight to studies with greater estimation precision. We did not apply any other effect-size corrections because this approach can lead to inaccurate conclusions about the effect-size population mean and variability (DeShon, 2002). As shown in Figure 1, we tested two meta-analytic path models (Viswesvaran & Ones, 1995) to determine if POS and organizational work–family support mediated the relationships between supervisor support and supervisor support for family and work–family conflict. Consistent with existing research (Carr, Schmidt, Ford, & DeShon, 2003), we used mean meta-analytic correlations as input along with smallest sample size on which these mean correlations were based. Using AMOS 5.0, we evaluated model fit using a variety of fit statistics including chi-square, CFI, and RMSEA. CFI values greater than 0.97 and RMSEA values less than 0.05 were used to indicate good fit (Kline, 2005).

Figure 1.

Path Analytic Results of Just Identified and Trimmed Models of General and Work–Family-Specific Support Relationships to Work-to-Family Conflict.

Nonindependent effect sizes

Because some work-to-family and social support measures can have multiple dimensions, several studies contributed multiple relevant, but nonindependent, effect sizes. For instance, work-to-family conflict is often measured as time-, strain- and behavior-based (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985), and social support can be measured as emotional, informational, and instrumental (House, 1981). Similar to previous studies of support in the workplace (e.g., Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002), whenever a study provided multiple effect sizes due to measuring work-to-family conflict or support at work using multiple unidimensional subscales, these effect sizes were transformed into a correlation of composite variables (see Hunter & Schmidt, 1990) and were treated as a single effect size (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001; Rosenthal and Rubin, 1986).

Results

Table 1 presents the bivariate meta-analytic results. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, work-to-family conflict was negatively and significantly correlated with organizational support (typically measured by POS; Mr = −0.22, Z = 4.83, p < 0.001), organizational work–family support (typically measured by FSOP; Mr = −0.36, Z = 13.80, p < 0.001), supervisor support (Mr = −0.15, Z = 6.39, p < 0.001), and supervisor work–family support (Mr = −0.25, Z = 19.16, p < 0.001). The magnitude of the mean correlations ranged from small to medium in size (Cohen, 1987). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

TABLE 1.

Meta-Analytic Results for Correlations General and Work–Family-Specific Workplace Support Variables and Work-to-Family Conflict

| Relationship | k | N | Effect-size variability

|

Effect-size centrality

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDr | Q | Mr | 95% CI for Mr | |||

| WFC & POS | 12 | 3,581 | 0.15 | 78.23* | −0.22* | −0.30, −0.13 |

| WFC& WFOP | 47 | 14,041 | 0.18 | 451.84* | −0.36* | −0.41, −0.31 |

| WFC & SS | 25 | 7,627 | 0.11 | 89.44* | −0.15* | −0.19, −0.10 |

| WFC & WFSS | 65 | 56,636 | 0.08 | 359.47* | −0.25* | −0.27, −0.22 |

| Meta-analytic correlations need for path analyses | ||||||

| POS & WFOP | 3 | 1,118 | 0.11 | 13.57* | 0.35* | 0.21, 0.49 |

| POS & SS** | 12 | 5,383 | 0.16 | 422.78* | 0.51* | |

| POS & WFSS | 5 | 958 | 0.18 | 30.71* | 0.50* | 0.35, 0.62 |

| FSOP & SS | 3 | 609 | 0.18 | 19.94* | 0.37* | 0.12, 0.57 |

| FSOP & WFSS | 35 | 10,080 | 0.18 | 313.33* | 0.32* | 0.26, 0.37 |

| SS & WFSS | 4 | 691 | 0.27 | 49.05* | 0.56* | 0.31, 0.74 |

Note. k = number of independent samples; N = number of subjects; SDr = standard deviation of correlations; Q = heterogeneity statistic for correlations; Mr = average-weighted correlation.

Significant at p < 0.05;

effect-size information in this row came from Rhoades and Eisenberger (2002).

Consistent with Hypothesis 2, the mean correlation between work-to-family conflict and supervisor work–family support (Mr = −0.25) was significantly stronger than the mean correlation between work-to-family conflict and general supervisor support (Mr = −0.15), χ2(1) = 10.07, p = 0.002. In addition, the mean correlation between work-to-family conflict and organizational support work–family support (Mr = −0.36) was significantly stronger than the mean correlation between work-to-family conflict and general organizational support (Mr = −0.22), χ2(1) = 6.13, p = 0.01.

An alternative approach to test Hypotheses 2 is to explore the unique effect of each support type on work–family conflict by including both general and family-specific forms in a multiple regression model predicting work–family conflict using as input the meta-analytic correlations presented in Table 1. The primary questions for these models were (a) to explore whether the observed, significant relationships between each support type and work–family conflict remained when controlling for the other type of support and (b) to test whether a model that constrained these unique relationships to equality fit the data well. Controlling for perceived organizational support, organizational work–family support remained significantly and negatively related to work–family conflict (b = −0.32, Z = −11.22, p < 0.001). Controlling for organizational work–family support, POS remained significantly and negatively related to work–family conflict (b = −0.11, Z = −3.72, p < 0.001). To test whether these partial relationships differed significantly, we compared the fit of a model that constrained these partial relationships to equality to the model where both relationships were freely estimated. The constrained model fit significantly worse than the unconstrained model, Δχ2 (1, N = 1,188) = 20.62, p < 0.001. Therefore, the partial relationship between perceived organizational work–family support and work–family conflict is greater in magnitude than the partial relationship between general organizational support and work–family conflict.

Controlling for general supervisor support, supervisor work–family support remained significantly and negatively related to work–family conflict (b = −0.24, Z = −5.44, p < 0.001). However, controlling for supervisor work–family support, general supervisor support was no longer significantly related to work–family conflict (b = −0.02, Z = −0.33, p = 0.74). To test whether these partial relationships differed significantly, we compared the fit of a model that constrained these partial relationships to equality to the model where both relationships were freely estimated. The constrained model fit significantly worse than the unconstrained model, Δχ2 (1, N = 691) = 8.32, p = 0.004. Therefore, the partial relationship between work–family supervisor support and work–family conflict is greater in magnitude than the partial relationship between general supervisor support and work–family conflict. Taken together, these results support Hypothesis 2.

Path model testing the mediating role of perceptions of organizational support and organizational work–family support

Hypothesis 3 predicted that organizational support and organizational work–family support would mediate the relationships between both supervisor support and supervisor work–family support and work-to-family conflict. Given that these predictors of work-to-family conflict are all positively correlated, we deemed it prudent to test these hypotheses in the context of a unified meta-analytic path model (Viswesvaran & Ones, 1995).

Before testing the model of interest, we estimated a just-identified model with paths from each type of supervisor support to each type of organizational support, as well as to work-to-family conflict, and with paths from each type of organization support to work-to-family conflict. Figure 1 presents the parameters of this model where significant paths are marked with an asterisk. Whereas the nonsignificant path between supervisor support and work-to-family conflict was consistent with our mediation hypotheses (b = 0.09, Z = 1.76, p = 0.08), the significance of two parameters in this model were not expected. First, supervisor work–family support had a significant direct effect on work-to-family conflict (b = −0.17, Z = 3.50, p < 0.001); second, organizational support had a nonsignificant direct effect on work-to-family conflict (b = −0.08, Z = 1.67, p = 0.10).

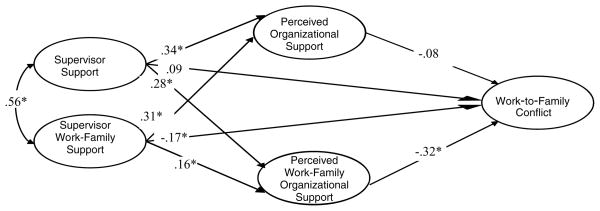

Using this information and for parsimony, we pruned the model to omit the nonsignificant paths. Figure 2 presents the parameters of this pruned model where significant paths are marked with an asterisk. This model fit the data well, χ2 (2, N = 609) = 5.50, p = 0.06, GFI = 0.99, CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.05, and did not differ significantly from the just-identified model, Δχ2 (2, N = 609) = 5.50, p = 0.06. Note that in this model, there is no path between organizational support and work-to-family conflict when controlling for the other predictors in the model. Thus, organizational support cannot mediate the impact of supervisor support on work-to-family conflict. Furthermore, supervisor work–family support has a significant, negative direct relationship to work-to-family conflict when controlling for the other predictors (b = −0.15, Z = −3.81, p < 0.001). These results contradict Hypothesis 3. However, two results suggest partial support for facets of Hypothesis 3. First, this model implies that supervisor support did not have a significant direct effect on work-to-family conflict when controlling for the other predictors. Second, using the Sobel test, we found a negative, significant, indirect relationship of supervisor work–family support to work-to-family conflict through organizational work–family support (Z = −5.50, p < 0.001). Interestingly, using the Sobel test, we found a significant, negative, indirect relationship of supervisor support to work-to-family conflict through organizational work–family support (Z = −6.79, p < 0.001). Overall, our findings suggest that organizational work–family support plays a critical mediating role in the relationships between supervisor support and work-to-family conflict and supervisor support for family and work-to-family conflict. In addition, work–family-specific support at both the supervisor and organizational level is strongly related to work-to-family conflict, when controlling for general social support from these sources.

Figure 2.

Path Analytic Results of Just Identified and Trimmed Models of General and Work–Family-Specific Support Relationships to Work-to-Family Conflict.

Discussion

The purpose of this article was to (a) test whether or not work–family-specific workplace social support is more strongly related to work–family conflict than general support, and (b) develop and test a path model of the interrelationships between different types and sources of workplace social support as related to work–family conflict in a single, simultaneous model. In testing our path model where we theorized that the relationship between supervisor support (both general and work–family specific) and work-to-family conflict was mediated by organizational support (both general and specific), we found that the meditational effects only held up for work–family-specific organizational support (Figure 2). In other words, both general and work–family supervisor support were related to work-to-family conflict via work–family organizational support. Further, supervisor work–family support had a direct relationship with work-to-family conflict when controlling for work–family organizational support. These results suggest that both work–family organizational support and work–family supervisor support (both directly and via work–family organizational support for the latter) are related to work-to-family conflict.

The partial mediation findings indicate that work–family-specific organizational support is not the only mechanism though which work–family-specific supervisor support relates to work–family conflict. These results do not challenge the fact that positive perceptions of work–family-specific organizational support are strongly related to work–family conflict reduction. Rather there are other unmeasured mediating variables than direct supervisor support effects that may be useful in alleviating work-to-family conflict. These may include decreasing job demands, workloads, and tight deadlines; and increasing employee perceptions of control over the timing and location of work through structural job design (Karasek, 1979). These are all potential factors that organizations and supervisors can influence.

Workplace Social Support and Work–Family Literature Implications

Overall, our results provide a clear pattern: that the form or type of workplace social support (whether it is general or content, i.e., work–family specific) that an employee receives from the workplace matters for work–family conflict, as does the source of support (i.e., supervisor or organization). Work–family-specific support seems to operate differently in terms of its relationship with work-to-family conflict than general support, according to whether the source is the organization or supervisor. As a result, this study shows how important it is in future research for scholars to take care in construct definition and measurement related to workplace social support and work–family conflict linkages. Currently, work–family studies sometimes are unclear in or confound the referent used (e.g., organization or supervisor, general or content-specific support) in the same construct, which should be avoided (c.f., Thompson, Beauvais, & Lyness, 1999).

A key implication of the path analytic findings is that when it comes to linkages between perceptions of general social support and work–family conflict, it is important for employees to feel that their organization cares about reducing work–family conflicts and that they are provided adequate resources to both do their job and manage their nonwork demands (Eisenberger et al., 1986). However, when it comes to perceptions of support for work and family and the relation to work–family conflict, it is potentially more important for supervisors to enact specific behaviors that are supportive of employees’ ability to balance work and family (Hammer et al., 2009; Thomas & Ganster, 1995) than it is for them to enact more general socially supportive behaviors (Caplan et al., 1975). The rationale for the recommendation is that this study clearly demonstrates that supervisors are the mechanism for shaping views of general and work–family-specific support and its association with work–family conflict.

Future research should focus on the supervisor’s role in the enactment of HR practices to manage newer and evolving workforce issues such as work and family relationships. It is only relatively recently work–family issues have entered the workplace as a mainstreamed supervisor leadership role (Kossek, Lewis, & Hammer, 2010). Many supervisors and firms are still in transition in shifting behaviors and cultures to be more explicitly supportive of work and family. New studies are needed to explicitly capture these managerial and organizational learning processes.

None of the studies in our database considered how perceptions of workplace support cascade across levels of analysis from supervisors to organizations to employee work–family conflict experiences. Longitudinal multilevel studies should increasingly include measures of both general and work–family-specific supervisor and POS. With few exceptions (i.e., Thompson, Jahn, Kopelman, & Prottas, 2004), work–family research neglects important cross-level or support relationships. Given the need for more multilevel work–family research, future studies should be conducted with further construct clarity in distinguishing between the measurement of supervisor and coworker support at the work-group level and organizational support at the cultural and policy levels. All of the studies we examined measured support at the individual perceptional level. Different types of support from different sources may have specific impacts on differential types of conflict and different mediators or moderators. For example, supervisor or coworker support may have a stronger relationship to work–family conflict in a high performance teamwork environment where the tasks are highly interdependent and employees learn to rely on one another, or cross-train to back each other up, than organizational support. Future research on workplace social support theory should also be further developed to theorize the conditions under which content-specific compared to content-general workplace support matters more for positive employee outcomes. Theories need to be enhanced to understand processes making the source of the support relevant or not and why, such as whether coworker or team support can substitute for supervisor support and in what contexts. For example, cultural contexts may vary, and future studies should also include analysis of cross-cultural contextual differences, as nationalities may vary in what types and sources of support are likely to be most strongly related to work–family conflict.

Omitted Variables

This study did not include measures of coworker support, work–family policies, family-to-work conflict, or work–family enrichment due to too few samples in the literature. Future studies clearly need to focus on these measures as a larger body of work accumulates. As employers move toward more virtual teams, and continue to flatten, it is critical to include measures of coworker support (general and work–family specific). Work–family enrichment (the degree to which work–family roles are positively experienced as complimentary) should also be included so research can assess not only how jobs relate to negative personal outcomes at home but also how work and work–family interactions can also be beneficial in personal lives. We also need studies to include more unmeasured variables that might mediate the relationship between supervisor support and work–family conflict (job demands, job control, workloads, and backlash for using flexibility).

Implications for Practice

Our critical assessment of the existing research has practical value as it helps organizations understand what types of workplace social support (i.e., work–family specific) leaders and employers should invest in to reduce work–family conflict and which sources (i.e., supervisors) are likely to be most effective (Hammer et al., 2009). Longitudinal research suggests (Hammer, Kossek, Bodner, Anger, & Zimmerman, 2011) there are many strategies that an organization can use to increase both work–family supervisor and work–family organizational support, such as training supervisors to be more work–family supportive. Increasing work–family-specific supervisor support perceptions could also increase take up of work–family supportive policies, which in turn may lead employees to perceive the organizational climate as more work–family supportive, which relates to lower work-to-family conflict. This study shows how important it is for organizations to invest in selecting and developing managers who are able to provide positive workplace social support for employees generally on the job and for work–family-specific issues.

Conclusion

Research on linkages between workplace social support and work–family conflict has increased dramatically over recent decades. Despite this expansion, more consolidation and agreement is needed in the work–family field on definitions, construct measurement, and recurring processes of study. Our study clearly shows that work–family-specific support is more strongly related to work to family conflict than general support. We also show both general and work–family-specific supervisor support relate to work–family conflict via perceptions of work–family organizational support. POS and social support are well-researched theoretical domains that span a number of disciplines across the social sciences, which will provide a continued theoretical springboard for advancement of the work–family field. They also are constructs offering vehicles to mainstream work–family measurement and research questions to integrate with core human resource and organizational behavior measures.

Increased attention to work–family-specific support will also enhance general effectiveness of human resource systems. Organizations are hiring increasing numbers of workers who are bringing their family demands with them while they are on the job. Given work–family conflict is associated with many health, well-being, and organizational outcomes (Eby et al., 2005; Kossek et al., 2010), by changing workplaces to be more socially supportive of positive work–family relationships, employment contexts serve a proactive role that shape critical employment and societal outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by the Work, Family and Health Network, which is funded by a cooperative agreement through the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant # U01HD051217, U01HD051218, U01HD051256, U01HD051276), National Institute on Aging (Grant # U01AG027669), Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, and National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (Grant # U010H008788). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of these institutes and offices. Special acknowledgement goes to Extramural Staff Science Collaborator, Rosalind Berkowitz King, Ph.D. (NICHD) and Lynne Casper, Ph.D. (now of the University of Southern California) for design of the original Workplace, Family, Health and Well-Being Network Initiative. Persons interested in learning more about the Network should go to http://www.kpchr.org/workplacenetwork/. We thank Lillian Eby and several anonymous reviewers for helpful comments, Krista Brockwood for editorial assistance, and Michigan State University for additional research support of several graduate students who helped with coding.

APPENDIX: Articles Included in the Meta-Analysis

- Adams GA, Woolf JL, Castro CA, Adler AB. Leadership, family supportive organizational perceptions and work-family conflict. Paper presented at the 20th Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Los Angeles, CA. 2005. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Allen TD. Family-supportive work environments: The role of organizational perceptions. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2001;58:414–435. [Google Scholar]

- Allen TD, Greenhaus JH, Foley S. Family-supportive work environments: Further investigation of mechanisms and benefits. Paper presented at 20th Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Los Angeles, CA. 2005. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Aryee S, Luk V. Work and nonwork influences on the career satisfaction of dual-earner couples. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 1996;49:38–52. [Google Scholar]

- Aujla S. The role of justice and support in reducing work–family conflict. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Industrial-Organizational Psychology; Atlanta, GA. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aycan Z, Eskin M. Childcare, spousal and organizational support in reducing work-family conflict for females and males. Sex Roles. 2005;53:453–471. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes BB, Heydens-Gahir HA. Reduction of work-family conflict through the use of selection, optimization, and compensation behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88:1005–1018. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrah J, Shultz K, Baltes B, Stolz H. Men’s and women’s eldercare-based work-family conflict: Antecedents and work-related outcomes. Fathering. 2004;2:305–330. [Google Scholar]

- Baruch-Feldman C, Brondolo E, Ben-Dayne D, Schwartz J. Sources of social support and burnout, job satisfaction, and productivity. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2002;7(1):84–93. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.7.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behson SJ. Which dominates? The relative importance of work-family organizational support and general organizational context on employee outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2002;61:53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bourg C, Wechler-Segal W. The impact of family supportive policies and practices on organizational commitment to the army. Armed Forces and Society. 1999;25(4):633–652. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen GL. Effects of leader support in the work unit on the relationship between work spillover and family adaptation. Journal of Family and Economic Issues. 1998;19:25–52. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce AM. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Wayne State University; Detroit, MI: 2005. An investigation of the role of religious support in reducing work-family conflict. [Google Scholar]

- Brotheridge CM, Lee RT. Impact of work-family interference on general well-being: A replication and extension. International Journal of Stress Management. 2005;12(3):203–221. [Google Scholar]

- Casper WJ, Buffardi L. Work-life benefits and job pursuit intentions: The role of anticipated organizational support. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2004;65:391–410. [Google Scholar]

- Casper L, Martin J, Buffardi L, Erdwins C. Work-family conflict, perceived organization support, and organizational commitment among employed mothers. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2002;7:99–108. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.7.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casper WJ, Harris C, Taylor-Bianco A, Kwesiga E. Supervisor support as a buffer to the work-family conflict work attitude relationship: A cross-cultural examination of Brazil and the U.S. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management; Anaheim, CA. 2008. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Cinamon RG, Rich Y. Work-family conflict among female teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2005;21:365–378. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A. Nonwork influences on withdrawal cognitions: An empirical examination of an overlooked issue. Human Relations. 1997;50(12):1511–1536. [Google Scholar]

- Dolcos SD. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. North Carolina State University; Raleigh, NC: 2007. Managing life and work demands: The impact of organizational support on work-family conflict in public and private sectors. [Google Scholar]

- Elloy DF, Mackie B. Overload and work-family conflict among Australian dual-career families: Moderating effects of support. Psychological Reports. 2002;91:907–913. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2002.91.3.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley S, Hangyue N, Lui S. How gender and perceived organizational support moderate the work stressors-WFC relationship. Asia Pacific Journal of Management. 2005;22(3):237–256. [Google Scholar]

- Ford MT, Heinen BA, Langkamer KL. Work and family satisfaction and conflict: A meta-analysis of cross-domain relations. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2007;91:57–80. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox M, Dwyer D. An investigation of the effects of time and involvement in the relationship between stressors and work-family conflict. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 1999;4(2):164–174. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.4.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frone MR, Yardley JK, Markel KS. Developing and testing an integrative model of the work-family interface. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2004;50:145–167. [Google Scholar]

- Frye NK, Breaugh JA. Family-friendly policies, supervisor support, work-family conflict, family-work conflict, and satisfaction: A test of a conceptual model. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2004;19(2):197–220. [Google Scholar]

- Fu C, Shaffer M. The tug of work and family: Direct and indirect domain-specific determinants of work-family conflict. Personnel Review. 2000;30(5):502–522. [Google Scholar]

- Gerjerts K, Butler AB. Coping with work-school conflict through social support. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Industrial-Organizational Psychology; Chicago, IL. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gooler LE. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. City University of New York; 1996. Coping with work-family conflict: The role of organizational support. [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb BH, Kelloway EK, Martin-Matthews A. Predictors of work-family conflict, stress and job satisfaction among nurses. The Canadian Journal of Nursing Research. 1996;28(2):99–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandey AA, Cordeiro BL, Michael JH. Work-family supportiveness organizational perceptions: Important for the well-being of male blue-collar hourly workers? Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2007;71:460–478. [Google Scholar]

- Grant-Vallone EJ, Ensher EA. An examination of work and personal life conflict, organizational support, and employee health among international expatriates. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2001;25:261–278. [Google Scholar]

- Haar JM. Work-family conflict and turnover intention: Exploring the moderation effects of perceived work-family support. New Zealand Journal of Psychology. 2004;33:35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Haar JM. Challenge and hindrance stressors in New Zealand: Exploring social exchange theory outcomes. International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2006;17(11):1942–1950. [Google Scholar]

- Hallett C. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of North Texas; Denton, TX: 1995. Strain, social support and the meaning of work for new mothers. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer L, Kossek E, Yragui N, Bodner T, Hanson G. Development and validation of a multidimensional scale of family-supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB) Journal of Management. 2009;35:837–856. doi: 10.1177/0149206308328510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman AH. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Texas A&M University; College Station, TX: 2004. An examination of the perceived direction of work-family conflict. [Google Scholar]

- Jahn EW. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. The City University of New York; New York, NY: 1998. The impact of perceived organizational and supervisory family support on affective and continuance commitment: A longitudinal and multilevel analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Julien M. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Queen’s University; Kingston, ON, Canada: 2007. Finding solutions to work-life conflict: Examining models of control over work-life interface. [Google Scholar]

- Kane DJ. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Michigan; Ann Arbor, MI: 2004. An exploratory study of workplace supports among Canadian health care employees. [Google Scholar]

- Karatype OM, Kilic H. Relationships of supervisor support and conflicts in the work-family interface with the selected job outcomes of frontline employees. Tourism Management. 2007;28:238–252. [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe OM, Uludag O. Supervisor support, work-family conflict, and satisfaction outcomes: An empirical study in the hotel industry. Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism. 2008;7:115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kinnunen U, Mauno S. Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict among employed women and men in Finland. Human Relations. 1998;51:157–177. [Google Scholar]

- Kraimer ML, Wayne SJ. An examination of perceived organizational support as a multidimensional construct in the context of expatriate assignment. Journal of Management. 2004;30(2):209–237. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert S. Added benefits: The link between work-life benefits and organizational citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Journal. 2000;23:801–815. [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre LM, Allen TD. Work-supportive family, family-supportive supervision, use of organizational benefits, and problem-focused coping: Implications for work-family conflict and employee well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2006;11(92):169–181. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.11.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre LM, Spector PE, Allen TD, Poelmans S, Cooper CL, O’Driscoll, Kinnunen U. Family-supportive organization perceptions, multiple dimensions of work-family conflict, and employee satisfaction: A test of model across five samples. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2008;73:92–106. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews RA, Bulger CA, Barnes-Farrell JL. Work social supports, role stressors, and work-family conflict: The moderating effect of age. Journal of Vocational Behavior (In press) [Google Scholar]

- Mirrashidi T. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. California School of Professional Psychology; Los Angeles, CA: 1999. Integrating work and family: Stress, social support and well-being among ethnically diverse women. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt KR. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Memphis; Memphis, TN: 2008. Modeling the relationship between traumatic caregiver stress and job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intentions. [Google Scholar]

- Muse LA. Work-family conflict, performance and turnover intent: What kind of support helps?. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management; Anaheim, CA. 2008. Aug, [Google Scholar]

- Muse LA, Harris SG, Giles WF, Field HS. Work-life benefits and positive organizational behavior Is there a connection? Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2008;29:171–192. [Google Scholar]

- Muse LA, Valcour M. Working manuscript. The multidimensional nature of work-family conflict and its relationships with social support, performance and turnover intent. [Google Scholar]

- Nielson TR, Carlson DS, Lankau MJ. The supportive mentor as a means of reducing work-family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2001;59:364–381. [Google Scholar]

- Odle-Dusseau HN, Greene-Shortidge GN, Britt TW. Antecedents and outcomes of family supportive supervisor behaviors. In Hammer L (Chair), Antecedents and outcomes of family supportive supervision. Symposium presented at the 25th Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Atlanta, GA. 2010. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- O’Driscoll M, Poelmans S, Spector P, Kalliath T, Allen T, Cooper C, Sanchez J. Family-responsive interventions, perceived organizational and social support, work-family conflict, and psychological strain. International Journal of Stress Management. 2003;10:326–344. [Google Scholar]

- Premeaux SF, Adkins CL, Mossholder KW. Balancing work and family: A field study of multidimensional, multi-role work-family conflict. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2007;28:705–727. [Google Scholar]

- Rankin BW. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. George Mason University; Fairfax, VA: 2005. Work, family, and role strain experienced by women of different social classes. [Google Scholar]

- Reinardy S. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Missouri-Columbia; 2006. Beyond the games: A study of the effects of life issues and burnout on newspaper sports editors. [Google Scholar]

- Russo JA, Waters LE. Workaholic worker type differences in work-family conflict. Career Development International. 2006;11:418–439. [Google Scholar]

- Seiger CP, Wiese BS. Social support from work and family domains as an antecedent or moderator of work-family conflicts? Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2009;75:26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer MA, Harrison DA, Gilley KM, Luk DM. Struggling for balance amid turbulence on international assignments: Work-family conflict, support and commitment. Journal of Management. 2001;27:99–121. [Google Scholar]

- Shafiro M. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Portland State University; Portland, Oregon: 2004. The effects of allocentricism, idiocentrism, social support and big five personality dimensions on work-family conflict. [Google Scholar]

- Shinn M, Wong N, Simko P, Ortiz-Torres B. Promoting the well-being of working parents; Coping social support, and flexible job schedules. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1989;17:31–55. [Google Scholar]

- Shockley KM, Allen TD. When flexibility helps: Another look at the availability of flexible work arrangements and work-family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2007;71:479–493. [Google Scholar]

- Singla N, Poteat L. A model of work antecedents and physical health outcomes of work interfering with family. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management; Anaheim, CA. 2008. Aug, [Google Scholar]

- Smith BD. Job retention in child welfare: Effects of perceived organizational support, supervisor support, and intrinsic job value. Children and Youth Services Review. 2005;27:153–169. [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Gardner D. Factors affecting employee use of work-life balance initiatives. New Zealand Journal of Psychology. 2007;36(1):3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Spector PE, Allen TD, Poelmans SAY, Lapierre LM, Cooper CL, O’Driscoll M, Sanchez JI, et al. Unpublished data from Collaborative International Study of Managerial Stress. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart D, Casper WJ, Henley AB. The effects of flexibility and work-family conflict on perceptions of organizational support. Paper presented at the 20th Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Los Angeles, CA. 2005. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Tay C, Quazi H. Supervisor support and interactions with work-family programs on employee outcomes. Paper presented at the 22nd Annual Conferenc of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology; New York, NY. 2007. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Tay C, Quazi H, Kelly K. A multidimensional construct of work-life system: Its link to employee attitudes and outcomes. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management; Atlanta, GA. 2006. Aug, [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BL. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Touro University International; Cypress, CA: 2007. The relationship between work-family conflict/facilitation and perception of psychological contract fairness among Hispanic business professionals. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas LT, Ganster DC. Impact of family-supportive work variables on work-family conflict and strain: A control perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1995;80(1):6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CA, Beauvais LL, Lyness KS. When work-family benefits are not enough: The influence of work-family culture on benefit utilization, organizational attachment, and work-family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 1999;54:392–415. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CA, Jahn EI, Kopelman RE, Prottas DJ. Perceived organizational family support: A longitudinal and multilevel analysis. Journal of Managerial Issues. 2004;16(4):454–465. [Google Scholar]

- Valcour M, Bagger J. Testing a four-component model of organizational work-family support. Paper presented at the 24th Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology; New Orleans, LA. 2009. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Van Daalen G, Willemsen TM, Sanders K. Reducing work-family conflict through different sources of social support. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2006;69:462–476. [Google Scholar]

- Voydanhoff P. The effects of work demands and resources on work-to-family conflict and facilitation. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66(2):398–412. [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth LL. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Utah; Salt Lake City, UT: 2003. The application of role identity salience to the study of social support and work-family interaction. [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth LL, Owens BP. The effects of social support on work-family enhancement and work-family conflict in the public sector. Public Administration Review. 2007;67(1):75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Warren JA, Johnson PT. The impact of workplace support on work-family role strain. Family Relations. 1995;44(2):163–169. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler CM. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Missouri; Columbia, MO: 1997. Work-family conflict: Buffering effects of organizational resources. [Google Scholar]

- Young C. Does social support moderate work-related stress in single mothers?. Paper presented at the 20th Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Los Angeles, CA. 2005. Apr, [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

This study did not include measures of coworker support, work–family policies, family-to-work conflict or work–family enrichment due to too few samples in the literature.

Contributor Information

ELLEN ERNST KOSSEK, Michigan State University.

SHAUN PICHLER, California State University.

TODD BODNER, Portland State University.

LESLIE B. HAMMER, Portland State University

References

- Allen TD. Family-supportive work environments: The role of organizational perceptions. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2001;58:414–435. [Google Scholar]

- Allen TD, Herst DE, Bruck CS, Sutton M. Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2000;5:278–308. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.5.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aumann K, Galinsky E. The state of health in the American workforce: Does having an effective workplace matter? New York, NY: Families and Work Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A, Demeroutti E. The job-demands resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology. 2007;22:309–328. [Google Scholar]

- Behson SJ. Which dominates? The relative importance of work-family organizational support and general organizational context on employee outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2002;61:53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan R, Cobb S, French J, Harrison R, Pinneau S. Job demands and worker health. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Carr JZ, Schmidt AM, Ford JK, DeShon RP. Climate perceptions matter: A meta-analytic path analysis relating molar climate, cognitive and affective states, and individual level work outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88:605–619. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb S. Social support as moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1976;38:300–314. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Willis TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeShon R. A generalizablity theory perspective on measurement error corrections in validity generalization. In: Murphy KR, editor. Validity generalization: A critical review. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 365–402. [Google Scholar]

- Eby LT, Casper WJ, Lockwood A, Bordeaux C, Brinley A. Work and family research in IO/OB: Content analysis and review of the literature (1980–2002) Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2005;66:124–197. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger R, Armeli S, Rexwinkel B, Lynch PD, Rhoades L. Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2001;86:42–51. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger R, Huntington R, Hutchison S, Sowa D. Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1986;71:500–507. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger R, Singlhamber F, Vandenberghe C, Sucharski I, Rhoades L. Perceived supervisor support: Contributions to perceived support and employee retention. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2002;87:565–573. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford MT, Heinen BA, Langkamer KL. Work and family satisfaction and conflict: A meta-analysis of cross-domain relations. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2007;91:57–80. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frone MR, Russell M, Cooper ML. Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1992;77:65–78. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.77.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff J, Mount MK, Jamison RL. Employer supported child care, work-family conflict, and absenteeism: A field study. Personnel Psychology. 1990;43:793–809. [Google Scholar]

- Grandey AA, Cropanzano R. The conservation of resources model applied to work-family conflict and strain. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 1999;54:350–370. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus JH, Beutell NJ. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review. 1985;10:76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer LB, Kossek EE, Bodner T, Anger K, Zimmerman K. Clarifying work–family intervention processes: The roles of work-family conflict and family supportive supervisor behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2011;96:134–150. doi: 10.1037/a0020927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer L, Kossek E, Yragui N, Bodner T, Hansen G. Development and validation of a multi-dimensional scale of family supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB) Journal of Management. 2009;35:837–856. doi: 10.1177/0149206308328510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges L, Olksin I. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV, Vevea JL. Fixed and random-effects models in meta-analysis. Psychological Methods. 1998;3:486–504. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan J, Holland B. Using theory to evaluate personality and job-performance relations: A socioanalytic perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88:100–112. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist. 1989;44:513–524. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS. Work stress and social support. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter J, Schmidt F. Methods of meta-analysis: Correcting error and bias in research findings. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Jex SM. Stress and job performance: Theory, research, and implications for managerial practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn RL, Wolfe DM, Quinn R, Snoek JD, Rosenthal RA. Organizational stress. New York, NY: Wiley; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek R. Job demands, job decision latitude and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1979;24:285–306. [Google Scholar]

- Kline R. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kossek E, Distelberg B. Work and family employment policy for a transformed work force: Trends and themes. In: Crouter N, Booth A, editors. Work-life policies. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press; 2009. pp. 3–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kossek EE, Lewis S, Hammer L. Work-life initiatives and organizational change: Overcoming mixed messages to move from the margin to the mainstream. Human Relations. 2010;63:1–17. doi: 10.1177/0018726709352385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kossek EE, Colquitt J, Noe R. Caregiving decisions, well-being and performance: The effects of place and provider as a function of dependent type and work-family climates. Academy of Management Journal. 2001;44:29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kossek EE, Nichol V. The effects of employer-sponsored child care on employee attitudes and performance. Personnel Psychology. 1992;45:485–509. [Google Scholar]

- Kossek EE, Ozeki C. Work-family conflict, policies, and the job-life satisfaction relationship: A review and directions for organizational behavior-human resources research. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1998;83:139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre LM, Allen TD. Work-supportive family, family-supportive supervision, use of organizational benefits, and problem-focused coping: Implications for work-family conflict and employee well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2006;11(92):169–181. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.11.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey M, Wilson D. Practical meta-analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Michel J, Michelson J, Pichler S, Cullen K. Clarifying relationships among work and family social support, stressors, and work–family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2010;76:91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Poelmans S. Work and family: An international research perspective. Mahwah, NJ: LEA/now part of Taylor and Francis; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades L, Eisenberger R. Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2002;87:698–714. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R, Rubin D. Meta-analytic procedures for combing studies with multiple effect sizes. Psychological Bulletin. 1986;99:400–406. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas LT, Ganster DC. Impact of family-supportive work variables on work-family conflict and strain: A control perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1995;80(1):6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CA, Beauvais LL, Lyness KS. When work-family benefits are not enough: The influence of work-family culture on benefit utilization, organizational attachment, and work-family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 1999;54:392–415. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CA, Jahn EI, Kopelman RE, Prottas DJ. Perceived organizational family support: A longitudinal and multilevel analysis. Journal of Managerial Issues. 2004;16(4):454–465. [Google Scholar]

- Viswesvaran C, Ones DS. Theory testing: Combining psychometric meta-analysis and structural equations modeling. Personnel Psychology. 1995;48:865–887. [Google Scholar]

- Viswesvaran C, Sanchez JI, Fisher J. The role of social support in the process of work stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 1999;54:314–334. [Google Scholar]