Abstract

Interleukin 17 (IL-17)-producing helper T cells (TH17 cells) require exposure to IL-23 to become encephalitogenic, but the mechanism by which IL-23 promotes their pathogenicity is not known. Here we found that IL-23 induced production of the cytokine granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) in TH17 cells and that GM-CSF played an essential role in their encephalitogenicity. Our findings identify a chief mechanism that underlies the important role of IL-23 in autoimmune diseases. IL-23 induced a positive feedback loop whereby GM-CSF secreted by TH17 cells stimulated the production of IL-23 by antigen-presenting cells. Such cross-regulation of IL-23 and GM-CSF explains the similar pattern of resistance to autoimmunity when either of the two cytokines is absent and identifies TH17 cells as a crucial source of GM-CSF in autoimmune inflammation.

INTRODUCTION

TH1 and TH17 cells are mediators of central nervous system (CNS) autoimmunity in both experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) and multiple sclerosis (MS) [reviewed in1]. The initial development of TH17 cells from naïve CD4+ T cells is directed by tumor growth factor-β (TGF-β) in combination with interleukin 6 (IL-6), IL-21 or IL-9 (refs.2-5) and this process is enhanced by tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and IL-1β6, whereas IL-23 is required for terminal differentiation of TH17 cells into mature effector cells7. Two types of TH17 cells, differing in their pathogenicity, have been described. TH17 cells stimulated with TGF-β plus IL-6 abundantly produced IL-17A and IL-10, but were not pathogenic, demonstrating that IL-17A production is not sufficient for TH17 cell encephalitogenicity8. IL-10 was shown not to be responsible for the non-pathogenic nature of these cells8. In contrast, stimulation with IL-23 resulted in highly encephalitogenic IL-10− TH17 cells, demonstrating that IL-23 induces expression of factors necessary for effector functions of these cells. TH17 cells secrete a range of inflammatory mediators including IL-9, IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-21, IL-22, TNF and GM-CSF. The role of IL-17A in EAE is controversial, with findings ranging from its complete dispensability9 to being essential10. Similarly, the role of IL-9 is also controversial3,11, while TNF, IL-21, IL-22 and IL-17F are not required for EAE development9,12-15. Failure to identify a soluble factor that mediates TH17 cell encephalitogenicity raises the question of whether the difference in pathogenicity of TGF-β plus IL-6- and IL-23-stimulated TH17 cells is caused by a secreted product or by a membrane-bound molecule(s).

Similar to IL-1-, IL-6- and IL-23-deficient mice16-18, GM-CSF-deficient mice do not develop EAE, nor do GM-CSF-deficient CD4+ T cells transfer EAE to naïve recipients19,20, demonstrating an essential role of GM-CSF in encephalitogenicity of T cells. More recently, GM-CSF secreted by CD4+ T cells, but not dendritic cells (DCs), has been shown to be critical in the development of autoimmune myocarditis by promoting IL-6 and IL-23 production by DCs, thereby enhancing TH17 differentiation21. The same group reported that CD4+ T cells isolated from the CNS of mice with EAE co-express IL-17A and GM-CSF at high frequency, suggesting that TH17 cell-derived GM-CSF is involved in EAE development21.

GM-CSF is produced by TH1, TH2 and TH17 cells22,23 and is the only known cytokine produced by T cells required for susceptibility to EAE. In this study, we identified GM-CSF as a critical factor in TH17 cell pathogenicity. Non-pathogenic TGF-β plus IL-6-treated TH17 cells express low amounts of GM-CSF compared to their pathogenic IL-23-driven counterparts, providing a mechanistic basis for the action of IL-23 on TH17 cells that renders them functionally mature. GM-CSF-deficient TH17 cells were unable to induce EAE, highlighting TH17 cells as a principal GM-CSF source in EAE.

RESULTS

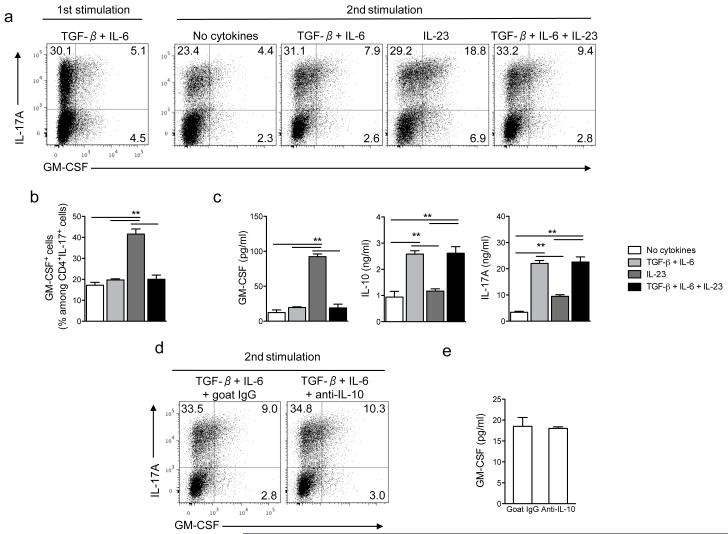

IL-23 upregulates GM-CSF in TH17 cells

Previous studies have established that TH17 cells produce GM-CSF21,22, but regulation of its production has not been studied. Here we characterized expression of GM-CSF by TH17 cells stimulated in different cytokine milieus. Naive CD4+ T cells were first differentiated into TH17 cells with TGF-β and IL-6 (first stimulation) and then reactivated (second stimulation) in the presence of various cytokines. During the first stimulation a fraction of IL-17A+ T cells expressed GM-CSF, and small amounts of GM-CSF were found in culture supernatants (Fig. 1a and data not shown). In the second stimulation, IL-23 increased the frequency of GM-CSF+ TH17 cells compared to cultures treated with TGF-β and IL-6 or without added cytokines (Fig. 1a,b). The combination of IL-23, TGF-β and IL-6 did not significantly increase the frequency of GM-CSF+ TH17 cells above stimulation with only TGF-β and IL-6 (Fig. 1a,b). Consistent with this finding, IL-23 significantly augmented GM-CSF secretion while TGF-β plus IL-6 or the TGF-β, IL-6 and IL-23 combination modestly increased GM-CSF production (Fig. 1c). TH17 cells restimulated either with TGF-β plus IL-6 or TGF-β alone had reduced production of GM-CSF while IL-6 did not have such a suppressive effect (Supplementary Fig. 1 and 2). As described previously8, TGF-β plus IL-6 treated TH17 cells secreted high amounts of IL-17A and IL-10 (Fig. 1c), and antibody blockade of IL-10 did not increase either frequency of GM-CSF+ TH17 cells or GM-CSF secretion (Fig. 1d,e). Apoptosis and cell counts in TH17 cells cultures stimulated in various conditions were similar, indicating that differences in cell death or proliferation did not influence cytokine production (Supplementary Fig. 3). TH17 cells differentiated by antigen-specific activation of splenocytes of 2D2 mice, transgenic for MOG35-55-specific TCR, also increased GM-CSF production during restimulation with IL-23 (Supplementary Fig. 4a-c). These results demonstrated that IL-23 induces GM-CSF expression by TH17 cells, while TGF-β has a dominant suppressive effect.

Figure 1. IL-23 upregulates GM-CSF expression in TH17 cells.

(a) Naive CD4+CD25−CD62LhiCD44lo T cells from spleens of C57BL/6 mice were sorted by flow cytometry and activated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 in the presence of TGF-β plus IL-6, anti-IFN-γ and anti-IL-4 for 72 h (first stimulation). Cells were rested 2 days in the presence of IL-2 and then reactivated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 (second stimulation) during 72 h in the presence of TGF-β plus IL-6, TGF-β, IL-6 and IL-23, IL-23 or without added cytokines. Cells were then stimulated with PMA and ionomycin in the presence of GolgiPlug for the final 4 h, stained and analyzed by flow cytometry. CD4+ cells are shown. (b) Percentage of GM-CSF+ cells among CD4+IL-17A+ cells after the second stimulation. (c) GM-CSF, IL-10 and IL-17A concentrations in cell culture supernatants after the second stimulation measured by ELISA. (d) TH17 cells restimulated in the presence of TGF-β and IL-6 for 72 h were treated with anti-IL-10 or isotype control (goat IgG) and analyzed by flow cytometry. (e) GM-CSF concentrations in culture supernatants of cells stimulated as in (d) measured by ELISA. **p< 0.001. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (error bars, s.e.m).

To determine if TH cells express GM-CSFR, rendering these cells susceptible to autocrine modulation by GM-CSF, we analyzed their expression of the receptor. We did not detect the presence of mRNA for GM-CSFRα in TH cells and flow cytometric analyses confirmed the lack of GM-CSFRα and GM-CSFRβ surface expression (Supplementary Fig. 5). Furthermore, differentiation of TH17 cells was not affected by addition of recombinant GM-CSF or blockade of endogenously produced GM-CSF (Supplementary Fig. 5c). Our data are in agreement with published findings that CD4+ T cells do not express a receptor for GM-CSF24,25 and are thus not directly modulated by this cytokine.

To test whether GM-CSF expression correlates with the pathogenicity of TH17 cells, we transferred either TGF-β plus IL-6- or IL-23-treated 2D2 TH17 cells to sublethally irradiated recipients. Mice injected with IL-23-treated 2D2 TH17 cells developed severe EAE and all succumbed 7 days after disease onset, while among mice injected with TGF-β and IL-6-treated 2D2 TH17 cells only two mice out of five developed mild disease (Supplementary Fig. 4d). These results reproduced previous findings8, demonstrating the essential role of IL-23 in the functional maturation of TH17 cells and establishing a correlation between production of GM-CSF and encephalitogenicity of TH17 cells.

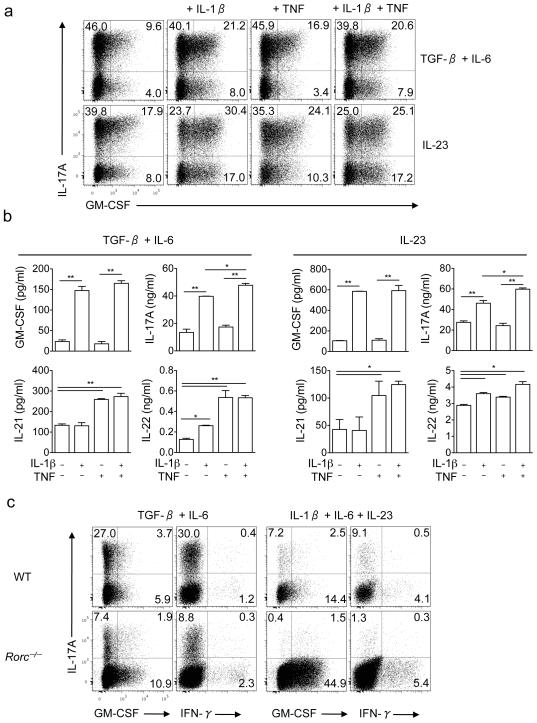

IL-1β upregulates production of GM-CSF by TH17 cells

IL-1β and TNF promote the development of TH17 cells6. To analyze their effect on GM-CSF production by committed TH17 cells, naive T cells were differentiated in the presence of TGF-β plus IL-6 and then restimulated in the presence of either IL-23 or TGF-β plus IL-6, and IL-1β and/or TNF. The presence of IL-1β in addition to IL-23 increased the percentage of GM-CSF+ cells while TNF had minimal effects (Fig. 2a). Consistent with these data, IL-1β greatly augmented GM-CSF and IL-17A secretion while TNF had a negligible effect (Fig. 2b). Addition of TNF enhanced secretion of both IL-21 and IL-22 while addition of IL-1β increased only IL-22 secretion (Fig. 2b). IL-1β also stimulated GM-CSF secretion by TH1 cells, while IL-12 and IL-23 had no effect (Supplementary Fig. 6). Interestingly, IL-1β in combination with IL-23 increased the proportion of GM-CSF+ cells in the IL-17A−CD4+ population (Fig. 2a). These IL-17A−GM-CSF+ cells were not TH1 cells because they did not produce IFN-γ and they expressed RORγt (data not shown).

Figure 2. IL-1β upregulates GM-CSF expression in TH17 cells.

(a) Naive CD4+CD25−CD62LhiCD44lo T cells from spleens of C57BL/6 mice were FACS sorted and differentiated into TH17 cells during the first stimulation. Cells were then reactivated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 for 72 h in the presence of either IL-23 or TGF-β plus IL-6, in the presence of IL-1β (10 ng/ml) and/or TNF (10 ng/ml). CD4+ cells are shown. (b) GM-CSF, IL-17A, IL-21 and IL-22 concentrations in cell culture supernatants after the second stimulation measured by ELISA. (c) Naive CD4+ T cells from spleens of C57BL/6 and RORγt-deficient mice were activated during 72 h with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 in the presence of either TGF-β and IL-6 or IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-23. Cells were then stimulated with PMA and ionomycin in the presence of GolgiPlug, stained and analyzed by flow cytometry. *p<0.01, **p < 0.001. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (error bars, s.e.m).

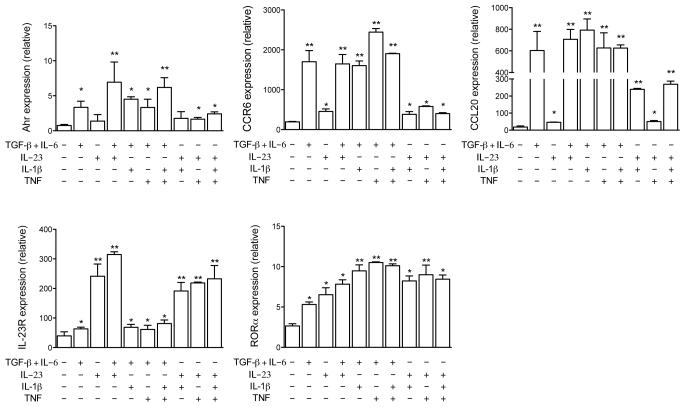

We examined TH17 specific markers when cells were restimulated in the presence of IL-1β and/or TNF and found that expression of Ahr, CCR6 and IL-23R were only modestly affected by the addition of IL-1β or TNF (Fig. 3). Both IL-1β and TNF increased expression of RORα in all conditions tested. In contrast, IL-1β increased CCL20 expression in IL-23-restimulated TH17 cells while TNF did not have such an effect.

Figure 3. Expression of TH17 cells markers is regulated by IL-1β and TNF.

Real-time PCR analysis of Ahr, CCR6, CCL20, IL-23R and RORα in TH17 cells reactivated with IL-23, TGF-β plus IL-6 or both in the presence of IL-1β (10 ng/ml) and/or TNF (10 ng/ml). *p < 0.01; **p < 0.001. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (error bars, s.e.m).

TGF-β strongly promoted expression of CCR6 on committed TH17 cells (Supplementary Fig. 1 and 7). Notably, IL-6 and, in particular, IL-23 counteracted the effect of TGF-β and markedly reduced the proportion of CCR6+ TH17 cells, whereas IL-1β had no effect. The ratio of approximately 1:1 between CCR6+GM-CSF+ and CCR6+GM-CSF− TH17 cells was similar in all conditions tested, demonstrating that expression of CCR6 and GM-CSF is independently regulated, which is also evident from the opposite effects of TGF-β and IL-23 on their expression. Among CNS-infiltrating CD4+ cells in EAE, 15-20% cells expressed CCR6 and approximately 30% expressed GM-CSF, but only a fraction of cells (5%) co-expressed GM-CSF and CCR6 (Supplementary Fig. 8), confirming our in vitro finding that their expression is not correlated. We also found that the lack of T-bet does not impact expression of CCR6 on TH17 cells (Supplementary Fig. 7), which eliminates the possibility that impaired encephalitogenicity of Tbx21−/− TH17 cells is caused by a defect in expression of this chemokine receptor.

IL-1β substantially upregulated GM-CSF production by TH1 and TH17 cells, a finding that led us to examine expression of IL-1R on these cells in EAE. IL-1R was expressed on 10-15% of CNS infiltrating CD4+ T cells. Only a minority (approx. 15%) of GM-CSF+ cells were also IL-1R+, while the highest percentage (20%) of IL-1R+ cells was found among IL-17A−IFN-γ− cells (Supplementary Fig. 9 and data not shown).

RORγt and T-bet are not required for GM-CSF production

RORγt and T-bet are signature transcription factors for TH17 and TH1 lineages, respectively, but TH17 cells express T-bet as well26. In all conditions tested, RORγt and T-bet expression were higher in IL-17A+GM-CSF+ than in IL-17A+GM-CSF− cells (Supplementary Fig. 10a), which suggested that, RORγt and/or T-bet might regulate GM-CSF expression in TH17 cells. Follow up experiments showed that wild-type and Tbx21−/− TH17 cells produced similar quantities of GM-CSF in vitro and had similar response to the cytokines that modify GM-CSF expression (Supplementary Fig. 2b,c, and Supplementary Fig. 7). In addition, splenocytes from immunized Tbx21−/− and wild-type mice produced similar quantities of GM-CSF upon stimulation with MOG35-55 ex vivo (data not shown). Overall, these data demonstrate that T-bet is not necessary for normal GM-CSF expression in TH cells.

We performed similar experiments to test the role of RORγt in GM-CSF production. CD4+ T cells of Rorc−/− mice activated in vitro produced similar or larger quantities of GM-CSF than did wild-type cells, depending on the cytokine milieu (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 10b). Similarly, splenic cells of Rorc−/− mice also produced large quantities of GM-CSF and had a comparable percentage of GM-CSF+ cells among CD4+ cells as did wild-type cells (data not shown). In contrast, splenocytes of Rorc−/− mice immunized with MOG35-55 produced little GM-CSF upon ex vivo restimulation with the peptide (Supplementary Fig. 10c,d), which could be, in part, due to 2- to 3-fold lower numbers of CD4+ T cells among Rorc−/− splenocytes compared to wild-type controls (data not shown). These data indicate that RORγt can have divergent roles in GM-CSF expression, depending on the type and strength of signals that the cell receives from its environment.

TH17 cells polarized without TGF-β produce GM-CSF

We also investigated GM-CSF production of TH17 cells that developed in the presence of IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-23, a recently described approach for differentiation of TH17 cells without TGF-β27. Development of TH17 cells in the absence of TGF-β was markedly reduced as assessed by flow cytometric analysis of IL-17A+ cells and IL-17A secretion (Supplementary Fig. 11), while production of GM-CSF was much higher, consistent with the inhibitory effect of TGF-β on GM-CSF production. This effect was even more pronounced in 2D2 splenic cultures than in those of purified CD4+ T cells (Supplementary Fig. 11 and Supplementary Fig. 2d). Surprisingly, upon secondary stimulation these cells largely ceased IL-17A production, while continuing to produce GM-CSF. Secretion of GM-CSF was not upregulated by IL-23, while IL-1β strongly enhanced GM-CSF secretion. These findings indicate that TH17 cells differentiated with IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-23 have a unique phenotype that requires further characterization.

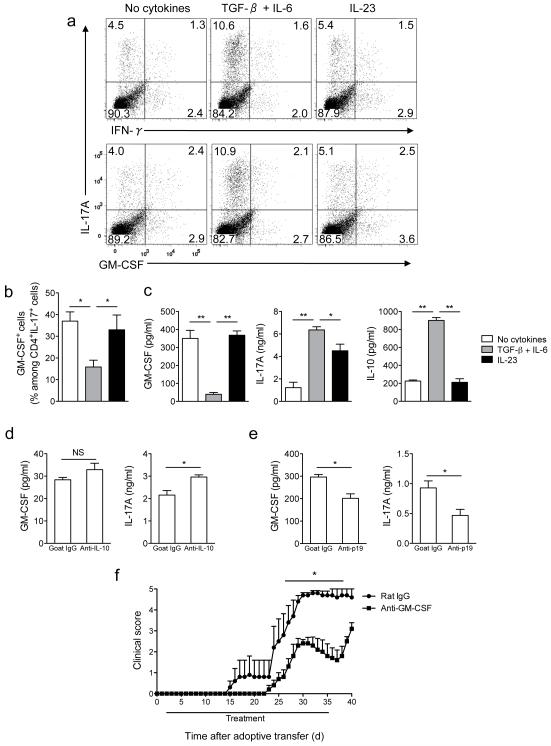

GM-CSF contributes to encephalitogenicity of TH17 cells

To analyze GM-CSF expression in TH17 cells that developed in vivo, splenocytes harvested from MOG35-55-immunized mice were stimulated ex vivo. The frequency of IL-17A+GM-CSF+ cells among CD4+ cells and GM-CSF production were similar in splenocytes stimulated in the presence of IL-23 or without added cytokines, but were decreased in TGF-β and IL-6 treated cells (Fig. 4a-c). TGF-β plus IL-6 treated splenocytes secreted elevated amounts of both IL-17A and IL-10 (Fig. 4c), and addition of neutralizing antibodies against IL-10 did not significantly increase GM-CSF secretion but did augment IL-17A production (Fig. 4d). Results obtained using splenocytes from immunized mice did not fully reproduce data with isolated CD4+ T cells, as IL-23 did not upregulate GM-CSF expression. A potential explanation for this discrepancy is that sufficient quantities of endogenous IL-23 are secreted during culturing to stimulate GM-CSF production similar to levels observed in IL-23-treated samples. Addition of anti-IL-23p19 significantly decreased secretion of both GM-CSF and IL-17A (Fig. 4e), confirming that endogenous IL-23 augments GM-CSF expression.

Figure 4. Neutralization of GM-CSF attenuates adoptive EAE.

(a) Splenocytes from MOG35-55-immuzed C57BL/6 mice were activated with MOG35-55 (20 μg/ml) in the presence of TGF-β plus IL-6, IL-23 or without added cytokines. Cells were then stimulated with PMA and ionomycin in the presence of GolgiPlug, stained and analyzed by flow cytometry. CD4+ cells are shown. (b) Percentage of GM-CSF+ cells among CD4+IL-17A+ cells after the second stimulation. (c) GM-CSF, IL-10, and IL-17A concentrations in cell culture supernatants measured by ELISA. (d) GM-CSF and IL-17A concentrations in supernatants of cell cultures stimulated as in (a) in the presence of TGF-β plus IL-6 and treated with anti-IL-10 or goat IgG. (e) GM-CSF and IL-17A concentrations in supernatants of cell cultures stimulated as in (a) without added cytokines and treated with anti-IL-23p19 or goat IgG (f) Clinical scores of irradiated wild-type recipient mice that received 5×106 CD4+ cells enriched from EAE splenocytes activated in the presence of IL-23. Mice were treated with either anti-GM-CSF or rat IgG from day 2 to day 35 post cell transfer. *p< 0.01; **p < 0.001. Data are representative of two (d, e and f) or four (a, b, and c) independent experiments (error bars, s.e.m).

To investigate the role of GM-CSF in TH17 cell pathogenicity, splenocytes from MOG35-55-immunized C57BL/6 mice were stimulated in the presence of IL-23 and injected into sublethally irradiated recipients. Mice treated with anti-GM-CSF developed significantly milder disease, with delayed onset, compared to control mice (Fig. 4f). Three mice out of five died in the control group while all mice in the anti-GM-CSF-treated group survived. When anti-GM-CSF treatment was stopped, mice started to develop more severe clinical signs of EAE (Fig. 4f).

These data suggested that GM-CSF produced by transferred TH cells is not essential for EAE development. We have addressed possibility that irradiation relinquishes requirement for GM-CSF in development of adoptive EAE and found that GM-CSF is indeed essential for EAE development in non-irradiated recipients (Supplementary Fig. 12). This prompted us to continue our experiments without irradiation of recipient mice, an approach that we believe more faithfully reproduces natural processes. We also found that host cells had infiltrated the CNS and produced GM-CSF, which markedly modified disease course in irradiated recipients (Supplementary Fig. 12). Our data showing that highly polarized Csf2−/− TH17 cells of MBPAc1-11 transgenic mice induce EAE in irradiated recipients do not necessarily contradict a previous report which showed that non-polarized cells from these mice are not encephalitogenic in irradiated recipients20. We used five times more highly polarized cells which we believe explains discrepancies between our and published findings20.

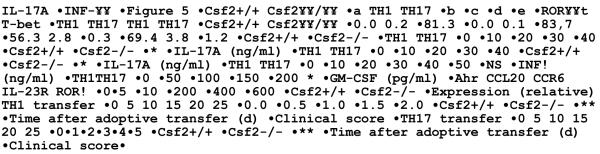

GM-CSF-deficient Th1 and TH17 cells are non-encephalitogenic

Neutralization of GM-CSF during IL-23-driven adoptive EAE in irradiated recipients resulted in less severe disease. Given that splenocytes of immunized mice contained multiple T helper subsets [5.4% IL-17A+ and 2.9% IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells], a definitive conclusion about the relevant cellular source of GM-CSF could not be drawn. To circumvent this problem we generated highly enriched TH1 and TH17 cells using splenocytes of GM-CSF-sufficient and -deficient mice transgenic for MBPAc1-11 TCR20 and injected them into non-irradiated recipients. In repeat experiments the percentages of TH1 and TH17 cells and their cytokine production in wild type and Csf2−/− cultures slightly varied irrespective of GM-CSF (Fig. 5a,b), confirming a previous report that GM-CSF has no significant effect on TH17 development driven by exogenous cytokines21. Wild-type and Csf2−/− cells expressed similar levels of Ahr, CCL20, CCR6, IL-23R, RORα, RORγt and T-bet (Fig. 5c,d).

Figure 5. GM-CSF production by TH1 and TH17 cells is required for their encephalitogenicity.

Splenocytes from wild-type- or Csf2−/−-MBPAc1-11 transgenic mice were activated with MBPAc1-11 peptide in the presence of IL-12 (TH1 conditions) or TGF-β plus IL-6, anti-IFN-γ and anti-IL-4 during 72 h (TH17 conditions). Cells were rested 2 days in the presence of IL-2 and then reactivated with MBPAc1-11 peptide in the presence of IL-12 (TH1 conditions) or IL-23 (TH17 conditions). After 72 h, cells were stimulated with PMA and ionomycin in the presence of GolgiPlug. (a) Flow cytometric analysis of IL-17A and IFN-γ expression in wild-type and Csf2−/− TH1 and TH17 cells after the second stimulation. CD4+ cells are shown. (b) IL-17A, IFN-γ and GM-CSF concentrations were measured by ELISA in the supernatants after the second stimulation. (c) RORγt and T-bet expression on gated CD4+IFN-γ+ (TH1) or CD4+IL-17A+ cells (TH17) analyzed by flow cytometry after the second stimulation. Filled histograms represent isotype controls. (d) Real time PCR analysis of Ahr, CCL20, CCR6, IL-23R and RORα expression in CD4+ T cells enriched by magnetic beads after the second stimulation from wild-type or Csf2−/− MBPAc1-11-splenocytes cultured in TH17 conditions. (e) Clinical scores of recipient mice that received 5×106 of either MBPAc1-11-specific wild-type or Csf2−/− TH1 or TH17 cells enriched by magnetic beads after the second stimulation. Pertussis toxin was injected i.p. on days 0 and 2 post transfer. *p< 0.01; **p < 0.001. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (error bars, s.e.m).

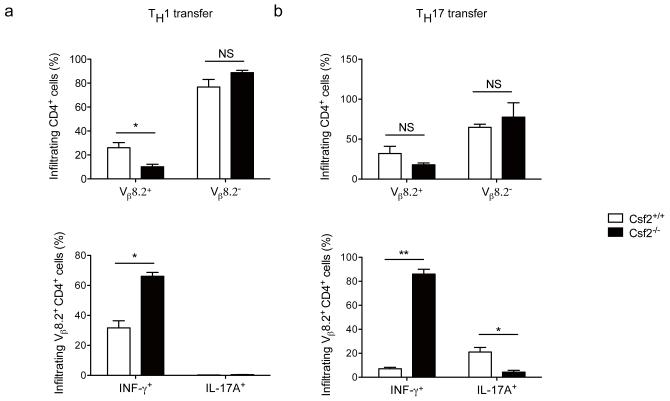

Two mice out of nine injected with Csf2−/− TH17 cells developed mild EAE while all mice that received wild-type TH17 cells developed severe disease. Similarly, all mice that received wild-type TH1 cells developed EAE while recipients of Csf2−/− TH1 cells did not (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 13). Transgenic MBPAc1-11-specific TCR contains Vβ8.2 chain, allowing tracking of these cells with anti-Vβ8.2 (ref. 20). Transferred Csf2−/− Vβ8.2+ TH1 and TH17 cells infiltrated the CNS, indicating that failure to induce EAE did not result from their inability to migrate into the CNS (Fig. 6). There were no consistent difference in the percentage of spinal cord-infiltrating CD4+ cells in the four experimental groups (data not shown), with CD4+Vβ8.2− host T cells representing the majority of CD4+ cells. Both transferred wild-type TH1 and TH17 cells had reduced expression of IFN-γ and IL-17A respectively, when compared to cells before injection, but Csf2−/− TH1 cells retained their phenotype while Csf2−/− Th17 cells drastically lost IL-17A expression and became IFN-γ producers (Fig. 6). Taken together, these data demonstrate that encephalitogenicity of TH1 and TH17 cells depends on their GM-CSF production, and that GM-CSF contributes to the maintenance of TH17 phenotype.

Figure 6. Csf2−/− TH1 and TH17 cells infiltrate the CNS but do not induce EAE.

EAE was induced as described in Figure 5. Spinal cords of TH1 (a) and TH17 cells (b) recipient mice were harvested at day 25 p.i. and mononuclear cells were isolated and stimulated with PMA, ionomycin, and GolgiPlug. Cells were then analyzed by flow cytometry for the expression of CD4, Vβ8.2 (upper panels), IL-17A and IFN-γ (lower panels). *p< 0.01; **p < 0.001. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (error bars, s.e.m).

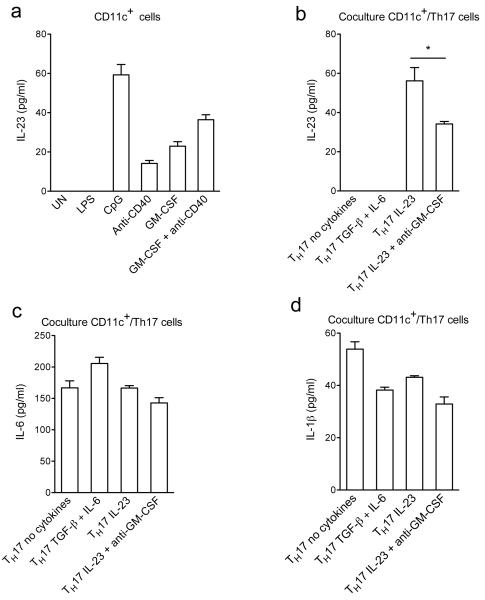

TH17 cells induce IL-23 production from CD11c+ cells

Previous studies have demonstrated that GM-CSF can augment production of proinflammatory cytokines by APCs21,28. Production of IL-6 and IL-1β by purified splenic CD11c+ cells was induced by CpG and LPS but not by anti-CD40 (data not shown). IL-23 production was induced by GM-CSF, CpG and to a lesser extent by anti-CD40, while LPS had no effect (Fig. 7a). GM-CSF enhanced IL-23 expression induced by anti-CD40, suggesting that GM-CSF produced by T cells can enhance IL-23 production by APCs. To test this hypothesis, we co-cultured CD11c+ cells with TH17 cells that differ in their capacity to produce GM-CSF. TH17 cells treated with TGF-β plus IL-6 or no added cytokines did not induce production of IL-23, while TH17 cells treated with IL-23 triggered secretion of IL-23 from CD11c+ cells, which was blocked by neutralization of GM-CSF (Fig. 7b). Levels of IL-1β and IL-6 in TH17 cell co-cultures were similar in all conditions tested (Fig. 7c,d). Taken together these data show that IL-23 can amplify its own production via induction of GM-CSF secretion by TH17 cells.

Figure 7. GM-CSF secreted by TH17 cells augments production of IL-23 by CD11c+ cells.

(a) CD11c+ cells isolated from splenocytes of C57BL/6 mice were stimulated with LPS, CpG, anti-CD40, rGM-CSF or left untreated (UN) for 24 h. (b), (c) and (d) Differentiated OT-II TH17 cells were cultured overnight in the presence of indicated cytokines, washed extensively, and then cocultured with CD11c+ cells and OVA323-339. Cytokine concentrations in supernatants were measured by ELISA. *p < 0.01. Data are representative of two independent experiments (error bars, s.e.m).

Given that GM-CSF affected IL-23 expression by APCs, we examined if it also modulates their IL-23R expression and therefore regulates autocrine/paracrine effects of IL-23 on APCs. Bone marrow-derived DCs expressed little or no IL-23R, and various types of stimulation in combination with GM-CSF did not upregulate expression of IL-23R (Supplementary Fig. 14). CD11b+ cells isolated from spleen did not express IL-23R, nor did they upregulate its expression in response to various stimuli and GM-CSF. In contrast, CD11c+ from spleen did express IL-23R, which was markedly upregulated by stimulation with LPS and CpG. However, GM-CSF had no effect on their IL-23R expression. Our findings are consistent with published work showing expression of IL-23R by only a small percentage of CD11b+ and CD11c+ cells from spleen29.

DISCUSSION

We examined regulation of GM-CSF production and found that IL-1β and IL-23 strongly upregulated GM-CSF expression by TH17 cells, which is required for EAE development. These findings identify the IL-23/TH17/GM-CSF axis as the major pathway in pathogenesis of autoimmune CNS inflammation and likely other autoimmune diseases. Th1 cells also produced GM-CSF and responded to IL-1β by increasing its production, making them another possible source of GM-CSF in EAE. However, recent findings that majority of CNS-infiltrating Th1 cells originate form Th17 cells30 blurs the distinction between these two Th lineages and makes unclear which one is the principal source of GM-CSF in EAE. A plausible model can be proposed where Th17 cells and their Th1 progeny (ex-Th17 cells) are essential in EAE, which includes a bulk of GM-CSF production, while classical Th1 cells play marginal role.

In a transfer model of colitis, RORγt-deficient T cells failed to induce disease and when restimulated ex vivo, they produced significantly less IL-17A, GM-CSF and IFN-γ than did RORγt-sufficient T cells31. We found that IL-17A+GM-CSF+ cells express higher levels of RORγt than IL-17A+GM-CSF−cells, indicating that RORγt may participate in GM-CSF expression in TH17 cells. However, RORγt-deficient cells produced large quantities of GM-CSF in TH17-polarizing conditions, demonstrating that this transcription factor is not required for GM-CSF production by CD4+ T cells. This conclusion is consistent with the fact that highly polarized wild-type TH1 cells, which do not express RORγt, also produce GM-CSF. In contrast to purified CD4+ T cells, splenocytes of Rorc−/− mice immunized with MOG35-55 did not produce GM-CSF upon ex vivo re-stimulation with the peptide whereas activation of the same splenocytes with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 resulted in abundant GM-CSF secretion. Taken together, our data show that RORγt is not absolutely needed for GM-CSF expression in CD4+ T cells, as strong mitogenic activation in vitro induces its production irrespective of RORγt, whereas CD4+ T cells that developed in vivo seem to require RORγt for optimal GM-CSF production. RORγt and RORα play synergistic and partially redundant functions during TH17 polarization32,33. Given that RORγt and RORα bind highly homologous DNA motifs, it is possible that RORα can compensate for the absence of RORγt in GM-CSF expression as well.

Expression of T-bet in both TH1 and TH17 cells is necessary for their encephalitogenicity26. Given that T-bet has the role of a master transcription factor in TH1 lineage differentiation, the requirement for its expression in development of encephalitogenic TH1 cells is apparent. However, its role in development/function of TH17 cells is less clear. Given that encephalitogenicity of TH1 and TH17 cells depends on both T-bet and GM-CSF, we hypothesized that T-bet plays a role in GM-CSF production. However, wild-type and Tbx21−/− TH1 and TH17 cells had similar production of GM-CSF and similar responses to the cytokines that modify GM-CSF expression. We also found that the lack of T-bet does not impact expression of CCR6 on TH17 cells, which eliminates the possibility that impaired encephalitogenicity of Tbx21−/− TH17 cells is caused by a defect in expression of this chemokine receptor. It has been proposed that T-bet influences function of TH17 cells by directly regulating expression of IL-23R34 and/or being required for IL-23 signaling35. However, in our experiments the enhancement of IL-17A and GM-CSF production by IL-23 was even stronger in Tbx21−/− than in wild-type cells, suggesting that T-bet is not required for IL-23R expression or signaling.

The CCR6-CCL20 axis is essential for the entry of TH17 cells into the CNS in the early phase of EAE36. The failure of Csf2−/− TH17 cells to induce EAE was not due to their inability to migrate to the CNS, given that wild-type and Csf2−/− TH17 cells expressed similar levels of CCR6 and CCL20 before transfer and infiltrated the CNS to a comparable degree. Similar results were obtained when wild-type and Csf2−/− TH1 cells were used to transfer EAE.

Our data and findings of others demonstrate that GM-CSF induces IL-23 in APCs, which in turn induce GM-CSF expression by TH17 cells, resulting in amplification of the inflammatory response21,28,37. Given that a variety of lymphocyte subsets, such as Tc17, γδT and NKT cells, express IL-23 receptor38-40 and can produce GM-CSF37,41,42, then the IL-23/GM-CSF amplification loop likely involves these cell types in addition to TH17 cells. In the effector phase of EAE, GM-CSF produced by encephalitogenic T cells is required for development of disease by activation of CNS microglia20. Given that microglia are known producers of IL-2343, production of GM-CSF in the CNS by encephalitogenic T cells can in turn induce IL-23 production and promote local activation or expansion/maturation of pathogenic TH17 cells.

Importantly, IL-23-deficient mice develop EAE when exogenous IL-23 is delivered into the CNS, indicating that IL-23 can act on already developed TH17 cells16. Sonderegger et al. demonstrated that GM-CSF produced by T cells indirectly promoted TH17 differentiation and proliferation through stimulation of IL-6 and IL-23 production by DCs and macrophages21. Our data indicate that GM-CSF also plays a role in maintenance of TH17 phenotype, as the vast majority of Csf2−/− TH17 cells ceased IL-17A production and started to produce IFN-γ, while a much higher proportion of Csf2+/+ cells retained TH17 phenotype. Given that TH cells do not express the GM-CSF receptor, the effect of GM-CSF in maintenance of TH17 phenotype must be indirect, perhaps through the action of GM-CSF on APCs, which in turn secrete TH17-promoting cytokines (i.e. IL-6, IL-23).

A recent publication by Hirota et al. proposes that TH17 and ex-TH17 cells primarily contribute to CNS inflammation, as a surprisingly small number of classical TH1 cells is found in the CNS during EAE, and they produced small amounts of cytokines including GM-CSF30. Thus, even though classical TH1 cells can produce GM-CSF it appears that they are not an important source of this cytokine in EAE. It is not known if TH17 to TH1 phenotype switch is required for productive EAE pathogenesis, or if TH17 cells would establish productive CNS inflammation without the contribution of ex-TH17 cells. T-bet is required for encephalitogenicity of TH17 cells26 and for the switch from TH17 to TH1 phenotype, raising the possibility that ex-TH17 cells are crucial in EAE pathogenesis.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that GM-CSF is required for the encephalitogenicity of both TH1 and TH17 cells. IL-23 induces production of GM-CSF in TH17 cells while IL-1β potently enhances GM-CSF production in both TH1 and TH17. Our findings suggest that IL-23-induced GM-CSF production in TH17 cells contributes to their phenotypic maturation into competent effectors. However, in addition to induction of GM-CSF, IL-23 likely has other effects on TH17 cells that promote their encephalitogenicity. We propose a positive feedback loop where IL-23 produced by APCs induces production of GM-CSF by TH17 cells, which in turn stimulates production of IL-23 in APCs. Increased/prolonged production of IL-23 results in stronger and longer-lasting TH17 responses, causing more profound inflammation. The role of GM-CSF in the pathology of MS is currently not known, but animal studies, including ours, strongly suggest that blocking GM-CSF activity may be a successful therapeutic strategy in MS.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are very grateful to P. Gonnella for critical review, K. Regan for editorial assistance and S. Yu for technical assistance. We also thank KaloBios Pharmaceuticals, Inc. for generously providing anti-GM-CSF. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the National Multiple Sclerosis Society and the M.E. Groff Foundation.

Appendix

METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6 (H-2b), 2D2 (H-2b), OT-II (H-2b), Rorc−/− (H-2b) and B10.PL (H-2u) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Tbx21−/− (H-2b) mice were purchased from Taconic. Myelin basic protein (MBP)-TCR transgenic mice specific for MBPAc1-11 and MBP-TCR-Csf2−/− mice have been described previously20. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Thomas Jefferson University.

Reagents

Anti-CD3 (145-2C11) and anti-CD28 (37.51) were purchased from BD Biosciences. The following antibodies for flow cytometry were from BD Biosciences: anti-CD4 (RM4-5), anti-CD69 (H1.2F3), anti-CD44 (IM7), anti-IFN-γ (XMG1.2), anti-IL-17A (TC11-18H10), anti-GM-CSF (MP1-22E9), anti-CCR6 (140706) and anti-CD16/32 (2.4G2). Anti-RORγt (AFKJS-9) and anti-T-bet (4B10) were from eBioscience. Anti-GM-CSFRα (M-20) and β (K-17) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-IL-1R (JAMA-147) was purchased from Biolegend. Neutralizing antibodies against IFN-γ (H22), IL-10 (AF-417-NA), IL-23p19 (AF1619) and IL-4 (AB-404-NA), all recombinant cytokines and Duoset ELISA kits used to quantify IL-17A, GM-CSF, IL-21, IL-22, IL-23, IL-6, IL-1β and IL-10 were from R&D Systems.

Cell preparation and culture

Naïve CD4+CD25−CD62LhiCD44lo T cells sorted by flow cytometry, or total splenocytes were cultured in IMDM supplemented with 5% FBS (Gibco BRL; Invitrogen), 100 μg/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 0.5 □2-mercaptoethanol. Purified CD4+ T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 (1 μg/ml) and anti-CD28 (1 μg/ml) in TH17 conditions (2 ng/ml TGF-β, 20 ng/ml IL-6) during 72 h. Differentiated TH17 cells were then rested 2 days in the presence of IL-2 (2 ng/ml), washed and replated for a second stimulation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 in the presence either of TGF-β plus IL-6, IL-23 (10 ng/ml), TGF-β plus IL-6 and IL-23 or medium during 72 h. Splenocytes from wild-type-, Csf2−/−-MBPAc1-11 transgenic mice or 2D2 mice were stimulated in the presence of MBPAc1-11 (5 μg/ml) or MOG35-55 peptide (20 μg/ml) respectively in TH17 or TH1 conditions (IL-12; 2 ng/ml) for 72 h. Differentiated TH17 cells were then rested 2 days in the presence of IL-2 (2 ng/ml), washed and replated for a second stimulation with peptide in the presence either of TGF-β plus IL-6, IL-23 (10 ng/ml) or medium. Differentiated TH1 cells were rested 2 days in the presence of IL-2 (10 ng/ml), washed and replated for a second stimulation with peptide in the presence of IL-12 (2 ng/ml) and IL-2 (10 ng/ml). Where indicated in figure legends, cultures were supplemented with anti-mouse IFN-γ (5 μg/ml), anti-mouse IL-4 (5 μg/ml), anti-mouse IL-10 (10 μg/ml), anti-mouse IL-23p19 (10 μg/ml), IL-1β (10 ng/ml) or TNF (10 ng/ml). After each stimulation period, cells were used for flow cytometric analysis and supernatants were used for cytokine measurement by ELISA.

Induction of EAE

For induction of active EAE, female 8- to 10-wk-old wild-type or Rorc−/− mice were immunized s.c. with 150 μg of MOG35–55 in CFA containing 5 mg/ml Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra (Difco), at two sites on the back. Mice were injected with 200 ng of pertussis toxin (Difco) in PBS i.p. on days 0 and 2.

For passive transfer of EAE, splenocytes from wild-type-, Csf2−/−MBPAc1-11 transgenic mice or 2D2 mice were stimulated in the presence of MBPAc1-11 (5μg/ml) or MOG35-55 peptide (20 μg/ml) respectively in TH1 or TH17 conditions as indicated above. After the second stimulation, CD4+ T cells were purified by magnetic microbeads cell sorting (MiltenyiBiotec) and were injected (5×106 cells/mouse) into healthy or sublethally irradiated (400 rad) syngeneic mice via the tail vein. Mice were given 200 ng of pertussis toxin i.p. on days 0 and 2 post cell transfer. EAE was clinically assessed by daily scoring using a 0 to 5 scale as follows: partially limp tail, 0.5; completely limp tail, 1; limp tail and waddling gait, 1.5; paralysis of one hind limb, 2; paralysis of one hind limb and partial paralysis of the other hind limb, 2.5; paralysis of both hind limbs, 3; ascending paralysis, 3.5; paralysis of trunk, 4; moribund, 4.5; death, 5.

Anti-GM-CSF treatment

Anti-GM-CSF monoclonal antibody (clone 22E9.11; ATCC) was kindly provided by KaloBios Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (South San Francisco). Anti-GM-CSF (400 mg diluted in 0.2 ml of PBS) was injected intraperitoneally into mice every second day starting on day 2 after EAE induction until day 35. As control, mice received control Rat IgG Abs (Jackson Immunoresearch) using the same injection protocols as above.

Isolation of CNS infiltrating cells

EAE mice were sacrificed and brains and spinal cords were removed and pooled after transcardial perfusion with PBS. Tissues were mechanically dissociated through a 100-μm strainer and washed with PBS. The resultant pellet was fractionated on a 60-30% Percoll step gradient by centrifugation at 300xg for 20 min. Infiltrating mononuclear cells were harvested from the interface, washed, counted, and analyzed by flow cytometry as described below.

Isolation of CD11c+ cells and coculture with TH cells

Spleens of C57BL/6 mice were digested during 30 min with collagenase plus Dnase I (Roche Applied Biosciences) at 37°C, and CD11c+ cells were purified by MACS using anti-CD11c magnetic beads (MiltenyiBiotec). Isolated CD11c+ cells (3×105 cells per well in 96 well-plate) were activated for 24 h with the following stimuli: LPS (1 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich), CpG (1 μM; Invivogen), rGM-CSF (10 ng/ml; R&D Systems) or anti-CD40 (4 μg/ml; eBioscience). For coculture experiments, 3×105 CD11c+ cells were cultivated for 24 h with OVA323-339 (20 μg/ml) and 6×105 differentiated OT-II TH17 cells. Concentration of anti-GM-CSF was 10 μg/ml.

Flow cytometry

For all intracellular staining, cells were stimulated for 4 h with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (50 ng/ml) and ionomycin (500 ng/ml) (both from Sigma) and treated with GolgiPlug (1 μg per 1×106 cells; BD Pharmingen). In the staining procedure, Fc receptors on cells were first blocked with anti-CD16/32 (2.4G2; BD Pharmingen) and surface and intracellular staining was performed following manufacturer’s instructions for staining using Fix & Perm reagents (Caltag Laboratories). Data were acquired on a FACSAria (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Treestar).

Real-time PCR

Total RNA from T cells was isolated by Trizol extraction (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and cDNA was synthesized with a reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). Primer pairs for quantitative real-time PCR were from Applied Biosystems Gene expression was analyzed by TaqMan real-timePCR (Applied Biosystems). Ribosomal 18S RNA was used as an endogenous control in all experiments. Error bars indicate SEM values calculated from −ΔΔCt values from triplicate PCR reactions, according to Applied Biosystems protocols.

Primers from Applied Biosystems

18s, Mm03928990_g1; Rorc, Mm01261022_m1; Rora, Mm00443103_m1; Ahr, Mm00478932_m1; CCR6, Mm01323931_m1; CCL20; Mm01268754_m1; Il23r, Mm00519943_m1.

Statistics

An unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis. For clinical EAE data, the area under the curve was calculated for each mouse over the indicated time period and these values were used to compare groups with an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test. Differences with P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goverman J. Autoimmune T cell responses in the central nervous system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:393–407. doi: 10.1038/nri2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bettelli E, et al. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:235–238. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elyaman W, et al. IL-9 induces differentiation of TH17 cells and enhances function of FoxP3+ natural regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:12885–12890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812530106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korn T, et al. IL-21 initiates an alternative pathway to induce proinflammatory T(H)17 cells. Nature. 2007;448:484–487. doi: 10.1038/nature05970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mangan PR, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta induces development of the T(H)17 lineage. Nature. 2006;441:231–234. doi: 10.1038/nature04754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM, Stockinger B. TGFbeta in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity. 2006;24:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGeachy MJ, et al. The interleukin 23 receptor is essential for the terminal differentiation of interleukin 17-producing effector T helper cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:314–324. doi: 10.1038/ni.1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGeachy MJ, et al. TGF-beta and IL-6 drive the production of IL-17 and IL-10 by T cells and restrain T(H)-17 cell-mediated pathology. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1390–1397. doi: 10.1038/ni1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haak S, et al. IL-17A and IL-17F do not contribute vitally to autoimmune neuro-inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:61–69. doi: 10.1172/JCI35997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uyttenhove C, Sommereyns C, Theate I, Michiels T, Van Snick J. Anti-IL-17A autovaccination prevents clinical and histological manifestations of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1110:330–336. doi: 10.1196/annals.1423.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nowak EC, et al. IL-9 as a mediator of Th17-driven inflammatory disease. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1653–1660. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coquet JM, Chakravarti S, Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI. Cutting edge: IL-21 is not essential for Th17 differentiation or experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2008;180:7097–7101. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kreymborg K, et al. IL-22 is expressed by Th17 cells in an IL-23-dependent fashion, but not required for the development of autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2007;179:8098–8104. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sonderegger I, Kisielow J, Meier R, King C, Kopf M. IL-21 and IL-21R are not required for development of Th17 cells and autoimmunity in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1833–1838. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang XO, et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by IL-17F. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1063–1075. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cua DJ, et al. Interleukin-23 rather than interleukin-12 is the critical cytokine for autoimmune inflammation of the brain. Nature. 2003;421:744–748. doi: 10.1038/nature01355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eugster HP, Frei K, Kopf M, Lassmann H, Fontana A. IL-6-deficient mice resist myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-induced autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2178–2187. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199807)28:07<2178::AID-IMMU2178>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuki T, Nakae S, Sudo K, Horai R, Iwakura Y. Abnormal T cell activation caused by the imbalance of the IL-1/IL-1R antagonist system is responsible for the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Int Immunol. 2006;18:399–407. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McQualter JL, et al. Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor: a new putative therapeutic target in multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med. 2001;194:873–882. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.7.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ponomarev ED, et al. GM-CSF production by autoreactive T cells is required for the activation of microglial cells and the onset of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2007;178:39–48. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sonderegger I, et al. GM-CSF mediates autoimmunity by enhancing IL-6-dependent Th17 cell development and survival. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2281–2294. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Infante-Duarte C, Horton HF, Byrne MC, Kamradt T. Microbial lipopeptides induce the production of IL-17 in Th cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:6107–6115. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mosmann TR, Cherwinski H, Bond MW, Giedlin MA, Coffman RL. Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J Immunol. 1986;136:2348–2357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyamoto T, et al. Myeloid or lymphoid promiscuity as a critical step in hematopoietic lineage commitment. Dev Cell. 2002;3:137–147. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park LS, Friend D, Gillis S, Urdal DL. Characterization of the cell surface receptor for granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1986;261:4177–4183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Y, et al. T-bet is essential for encephalitogenicity of both Th1 and Th17 cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1549–1564. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghoreschi K, et al. Generation of pathogenic T(H)17 cells in the absence of TGF-beta signalling. Nature. 2010;467:967–971. doi: 10.1038/nature09447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleetwood AJ, Lawrence T, Hamilton JA, Cook AD. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (CSF) and macrophage CSF-dependent macrophage phenotypes display differences in cytokine profiles and transcription factor activities: implications for CSF blockade in inflammation. Journal of immunology. 2007;178:5245–5252. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Awasthi A, et al. Cutting edge: IL-23 receptor gfp reporter mice reveal distinct populations of IL-17-producing cells. Journal of immunology. 2009;182:5904–5908. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirota K, et al. Fate mapping of IL-17-producing T cells in inflammatory responses. Nature immunology. 2011;12:255–263. doi: 10.1038/ni.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leppkes M, et al. RORgamma-expressing Th17 cells induce murine chronic intestinal inflammation via redundant effects of IL-17A and IL-17F. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:257–267. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang XO, et al. T helper 17 lineage differentiation is programmed by orphan nuclear receptors ROR alpha and ROR gamma. Immunity. 2008;28:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ivanov II, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126:1121–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gocke AR, et al. T-bet regulates the fate of Th1 and Th17 lymphocytes in autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2007;178:1341–1348. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Y, et al. Anti-IL-23 therapy inhibits multiple inflammatory pathways and ameliorates autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1317–1326. doi: 10.1172/JCI25308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reboldi A, et al. C-C chemokine receptor 6-regulated entry of TH-17 cells into the CNS through the choroid plexus is required for the initiation of EAE. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:514–523. doi: 10.1038/ni.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verreck FA, et al. Human IL-23-producing type 1 macrophages promote but IL-10-producing type 2 macrophages subvert immunity to (myco)bacteria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:4560–4565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400983101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rachitskaya AV, et al. Cutting edge: NKT cells constitutively express IL-23 receptor and RORgammat and rapidly produce IL-17 upon receptor ligation in an IL-6-independent fashion. J Immunol. 2008;180:5167–5171. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu-Kuo JM, Austen KF, Katz HR. Post-transcriptional stabilization by interleukin-1beta of interleukin-6 mRNA induced by c-kit ligand and interleukin-10 in mouse bone marrow-derived mast cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1996;271:22169–22174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.22169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ciric B, El-behi M, Cabrera R, Zhang GX, Rostami A. IL-23 drives pathogenic IL-17-producing CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:5296–5305. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamazaki T, et al. CCR6 regulates the migration of inflammatory and regulatory T cells. Journal of immunology. 2008;181:8391–8401. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheibanie AF, Tadmori I, Jing H, Vassiliou E, Ganea D. Prostaglandin E2 induces IL-23 production in bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. Faseb J. 2004;18:1318–1320. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1367fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li J, et al. Differential expression and regulation of IL-23 and IL-12 subunits and receptors in adult mouse microglia. J Neurol Sci. 2003;215:95–103. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(03)00203-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.