Abstract

Abstract

A conflict of interest is defined as “a set of conditions in which professional judgment concerning a primary interest (such as a patient’s welfare or the validity of research) tends to be unduly influenced by a secondary interest (such as financial gain)” [Thompson DF. Understanding financial conflicts of interest. N Engl J Med 1993;329(8):573–576]. Because financial conflict of interest (fCOI) can occur at different stages of a study, and because it can be difficult for investigators to detect their own bias, particularly retrospectively, we sought to provide funders, journal editors and other stakeholders with a standardized tool that initiates detailed reporting of different aspects of fCOI when the study begins and continues that reporting throughout the study process to publication. We developed a checklist using a 3-phase process of pre-meeting item generation, a stakeholder meeting and post-meeting consolidation. External experts (n = 18), research team members (n = 12) and research staff members (n = 4) rated or reviewed items for some or all of the 7 major iterations. The resulting Financial Conflicts of Interest Checklist 2010 consists of 4 sections covering administrative, study, personal financial, and authorship information, which are divided into 6 modules and contain a total of 15 items and their related sub-items; it also includes a glossary of terms. The modules are designed to be completed by all investigators at different points over the course of the study, and updated information can be appended to the checklist when it is submitted to stakeholder groups for review. We invite comments and suggestions for improvement at http://www.openmedicine.ca/fcoichecklist and ask stakeholder groups to endorse the use of the checklist.

A conflict of interest is defined as “a set of conditions in which professional judgment concerning a primary interest (such as a patient's welfare or the validity of research) tends to be unduly influenced by a secondary interest (such as financial gain).”1 Conflict of interest in biomedical research is a complex issue that has received a great deal of attention. The focus of the 2009 Institute of Medicine report on conflict of interest highlights the importance of this issue.2 When there are financial interests in research studies there is concern that these relationships may influence research outcomes.3 Despite the importance of this issue, there is considerable variability in the way that these relationships have been reported.2,3 To protect research participants and maintain public trust in research, it is important that potential financial conflicts of interest (fCOIs) are disclosed and steps are taken, where indicated, to manage their effects.2

Investigators may not always recognize their own potential conflicts of interest and therefore would benefit from a structured method of documenting and reporting fCOI to stakeholders for assessment purposes.2,4 When we began this project in January 2007, various fCOI reporting disclosures were required by different stakeholder groups such as funders,5 academic institutions,6 and journal editors.7 These disclosures were not coordinated and were typically collected using different reporting formats (e.g., fCOI forms, fCOI statements). This meant that investigators might need to complete multiple different conflict of interest reporting disclosures for their study in order to meet the needs of different stakeholders.

We sought to provide stakeholders with a single structured checklist that contains detailed information about different aspects of fCOI. Further, we placed this information within the context of a specific clinical research study to facilitate assessment of the potential impact of the financial relationship on the research. By using a prospective format, potential conflicts can be identified at an early stage in the research process and managed where required. The checklist is initiated when the study begins and is updated throughout the study process to publication. Although we designed the checklist for clinical research studies, we recognize that other types of studies have the potential to be influenced by fCOIs.

Developing the Financial Conflicts of Interest Checklist 2010

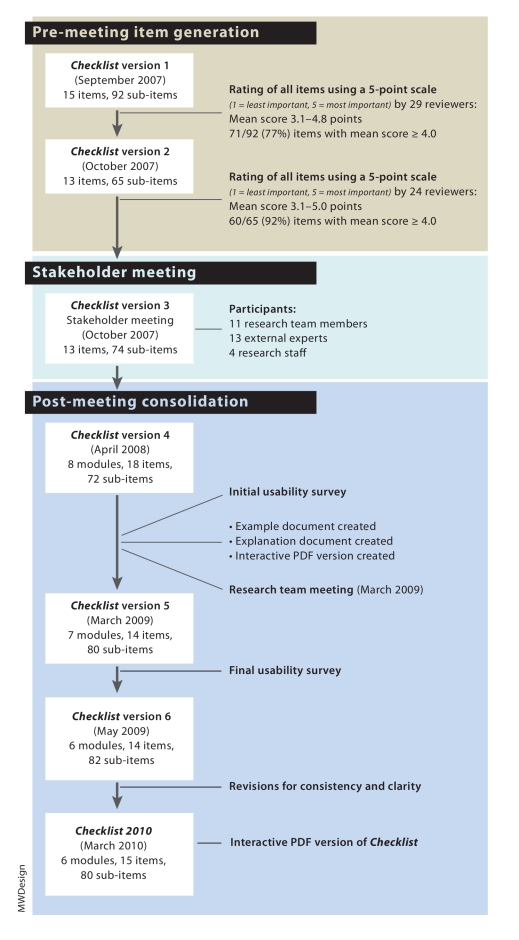

We developed the checklist using a 3-phase process of pre-meeting item generation, a stakeholder meeting, and post-meeting consolidation. This process, shown in Figure 1, was adapted from one described in a recent report on developing health research reporting guidelines.8 Contributors to the development of this checklist are listed in the Acknowledgments.

Figure 1.

Financial Conflicts of Interest Checklist 2010 development process

Pre-meeting item generation

The checklist items were generated initially by our research team, whose members have expertise in research, ethics boards, law and policy, trial registration, research administration, clinical research and research guideline development—specifically the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) and Enhancing QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research (EQUATOR) Network—and were based primarily on the published literature. We identified potential items from international initiatives targeting specific aspects of fCOI. For example, items related to trial registration were derived from the World Health Organization trial registration initiative,9 and items related to roles in manuscripts were drawn from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) guidelines on authorship in medical publishing4,7 and the World Association of Medical Editors guidelines on authorship.10

After compiling an initial list of 15 items and 92 sub-items, we reviewed it using 3 groups: external experts (n = 18) with expertise in trial registration, research guideline development (CONSORT, EQUATOR), ethics review, government administration policy, health law, medical journals and media; members of the research team (n = 12); and members of our research staff (n = 4). Research staff members were included to provide a perspective from non-experts with experience in the research process.

Reviewers were asked to rate the importance of each of the items using a 5-point scale (1 = least important, 5 = most important) and to provide free-text suggestions for improving them. On the basis of these responses, we developed a second version of the checklist and, 1 month later, sent it to the participants for review. Not all of the reviewers were available for both rating sessions: 29 provided feedback to version 1, and 24 provided feedback to version 2.

Stakeholder meeting

A total of 28 people participated in a day-long stakeholder meeting in October 2007 in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. In attendance were 11 research team members and 4 research staff; 13 external experts participated using web-teleconference connections from 4 countries. We presented draft version 3 of the checklist for item discussion and identified areas for revision. The meeting was organized into 4 thematic sessions reflecting the requirements and concerns of major stakeholder groups (clinical trial registry users, journal editors, funders and policymakers, and legal and ethics review board representatives). Each external expert participated in 1 session based on his or her area of expertise. Each session began with an overview of the checklist project, followed by a description of the particular thematic area; the session chair then led a discussion focusing on items that received discrepant ratings in the pre-meeting reviews.

Post-meeting consolidation

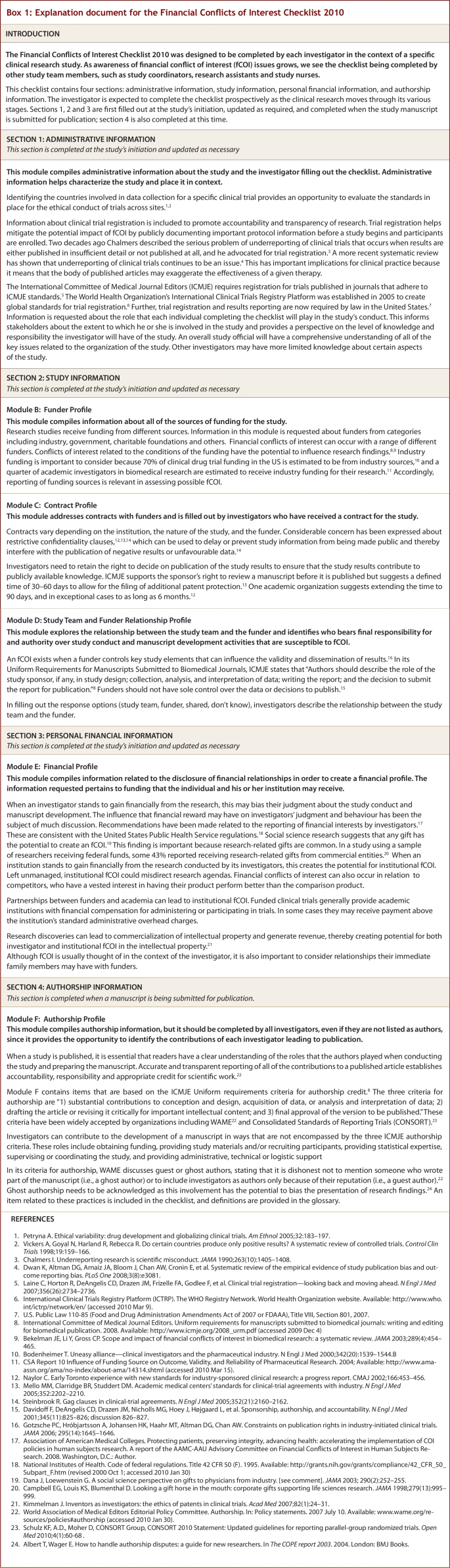

The post-meeting consolidation phase involved 3 steps. First, the research team incorporated the changes suggested at the stakeholder meeting into draft version 4 of the checklist—including dividing the items into modules—and then pilot-tested this version for usability with a small group of 6 investigators. We also created an example document showing examples of good reporting, an explanation document providing evidence and rationales for the items, and an interactive PDF version of the checklist.

Second, the research team met in Toronto for a 1-day consolidation meeting in March 2009 and reviewed the checklist by module and item. We reworded and reorganized items for greater clarity, decided to create a glossary to facilitate shared understanding and usage of key terms used in the items, and discussed how to improve the usability of the PDF version. We also had further discussions on how we envisioned the checklist would be implemented in practice.

In the third step of the post-meeting consolidation phase, we incorporated the most recent changes into draft version 5 of the checklist. Definitions for the glossary terms were incorporated as roll-over pop-ups attached to the terms in the PDF. We revised the corresponding example and explanation documents and pilot-tested the checklist again for usability. After successive revisions for consistency and clarity to the draft version 6 checklist and the corresponding interactive PDF, version 7 of the Financial Conflicts of Interest Checklist 2010 was created.

Ethical review and approval of the checklist process was obtained from the Baycrest Centre and Women’s College Research Institute Ethics Board, where the principal investigator was located.

The Financial Conflicts of Interest Checklist 2010

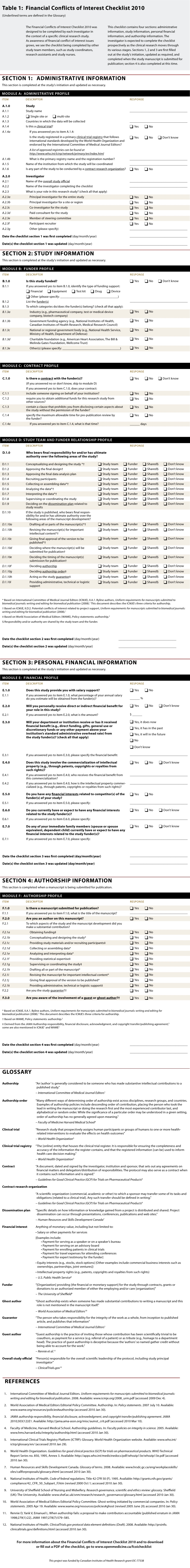

The Financial Conflicts of Interest Checklist 2010 (online Table 1) consists of a 15-item form and a glossary of terms with definitions derived from sources obtained from our literature review. The checklist is also available as an interactive PDF (see the online Appendix). A feature of the PDF format is that it uses “skip logic”; it presents to investigators only selections relevant to them at the time of checklist completion based on their answers. The glossary is incorporated into the PDF through pop-ups that provide the definition when a mouse rolls over a glossary term.

Table 1.

Financial Conflicts of Interest Checklist 2010

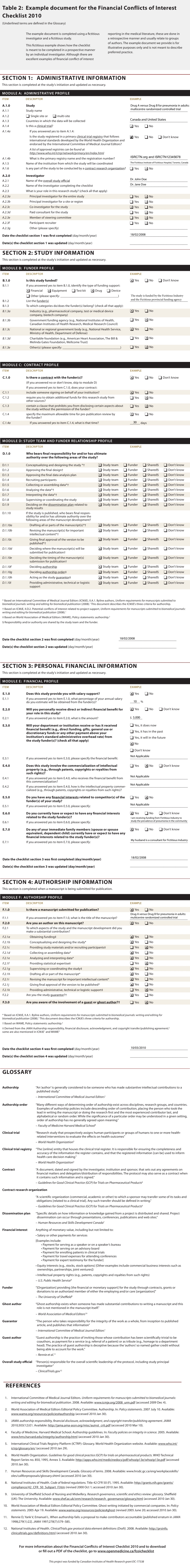

The 4 sections of the checklist cover administrative information, study information, personal financial information and authorship information. These sections are divided into 6 modules containing a total of 15 items and their related sub-items. The Administrative Information section contains module A, which compiles administrative information about the study and investigator, and the date(s) when the checklist was first filled out and subsequently updated. The Study Information section contains modules B to D, which create a funder profile, contract profile, and study team and funder relationship profile respectively. The Personal Financial Information section contains module E, which creates a financial profile for each investigator of the study and author of any study publication. Finally, the Authorship Information section contains module F, which creates an authorship profile for each author involved in manuscript preparation. We have also provided an example document (online Table 2), which presents examples of good reporting, and an explanation document (online Box 1), which presents rationales and evidence for each of the 6 modules.

Table 2.

Example document for the Financial Conflicts of Interest Checklist 2010

Box 1.

Explanation document for the Financial Conflicts of Interest Checklist 2010

The checklist was designed as a living document that is updated as the study progresses. In general, sections 1 to 3 will be completed at study initiation and updated as necessary (for example, section 3, the Personal Financial Information section, would require updating if the investigator’s financial profile changed); section 4 will be completed when a manuscript is being prepared for publication. We anticipate that updated information would be appended to the originally completed checklist to maintain a permanent record of information related to fCOI throughout the course of the study.

We recognize that clinical research and, in particular, clinical trials are generally conducted by a team of investigators. We recommend that each investigator independently complete the entire checklist. When the checklist is submitted to a stakeholder for review, the person most knowledgeable about the study, such as the overall study official (in the case of clinical trials) or study guarantor (in the case of a manuscript submission), would collate sections of the checklist that have shared information (i.e., module A: Administrative Profile, module B: Funder Profile and module C: Contract Profile).

We pilot-tested the checklist twice during the post-meeting consolidation phase. Of the 17 participants in these usability surveys, 13 (76%) had served as an investigator in a randomized trial. Eleven (65%) respondents reported no difficulty in answering the questions. Although the checklist should be completed at different stages of the study process, for the purposes of determining usability respondents were asked to estimate the time required to complete the entire checklist: 16 (94%) required less than 20 minutes.

Discussion

We have created a checklist that aims to promote transparency at all stages of the research and publication process. An important feature of our checklist is that, as a record completed by investigators as the study evolves, it can be given to the various stakeholders who are involved at different stages of the clinical research process—funding agencies, research ethics boards, trial registries, research administrators and journal editors—which is a more consistent, efficient and effective approach than providing each group with separate, disjointed disclosures. As well, since the type of fCOI information required by stakeholders varies substantially, use of the checklist may help standardize the information.

Prospective completion of the checklist means that there is an ability to elicit fCOI disclosures throughout the study’s “life stages” (e.g., from study inception to dissemination) and to maintain a public record of this information for its duration. There are 2 benefits to identifying potential fCOI situations at an early stage. First, it allows appropriate management to minimize harms; for example, the situation can be referred to a conflict of interest committee. The Institute of Medicine report Conflict of interest in medical research, education, and practice2 outlines steps for identifying and responding to such a committee. Second, it leads to more accurate reporting of fCOI. Investigators may be in an fCOI situation while they are conducting a study but divest themselves of it by the time they are submitting the study results for publication; such an fCOI may not be readily apparent to journal editors. The ICMJE recently published a new disclosure form for competing interests that is completed by authors at the end of a study, during the publication phase.11 The form is used by journal editors, and consensus for the form’s use has been built among all ICMJE journals. Given that the disclosure is occurring at the end of the research process, the opportunity to intervene and manage the fCOI is lost.

The checklist may have an educational role in that it is designed to be completed by each investigator. We recognize that clinical research is generally conducted by a team of investigators. When all investigators are asked to complete the entire checklist, irrespective of their role in the study, they will become sensitized to important issues about their study. Academic policies do not always provide investigators with clear guidance to assist them in identifying and reporting situations that may be relevant to fCOI. Further, national surveys of fCOI policies in academic settings suggest that these policies are often incomplete,6,12,13 fragmented12 and difficult for investigators to understand,12,14 all of which limit their practical usability by investigators. Although the checklist will likely initially be completed by investigators only, it is also relevant to other study team members who may be affected by fCOI, such as study coordinators, research assistants and study nurses.

The checklist has been designed so that a completed version can be attached along with a completed CONSORT checklist in the setting of a clinical trial.15 The checklist can have an application beyond clinical research studies, and we anticipate that it will be adapted for use for other types of studies, such as basic science research. It can also be adapted for use outside of the research setting. For example, modified versions could be completed by grant review panel members making funding decisions, guideline panel members making decisions about best practices, board members making decisions about the direction of an academic organization, and by expert witnesses providing expert opinions in court proceedings or tribunals. Accordingly, we designed the checklist with sections, modules and items so that it can be tailored for use in a range of settings.

The checklist has limitations. First, our checklist was designed to focus exclusively on financial conflicts of interest. We recognize that there are non-financial conflicts of interest, but these are known to be difficult to define.16 Financial conflicts of interest are the most well recognized and the most quantifiable.1 Second, although there are only 15 items, some users may feel daunted by the detail requested in a few of the sub-items. Our pilot testing revealed a checklist completion time of less than 20 minutes. Importantly, the entire checklist need not—and likely should not—be completed at one time. As we have recommended, different modules should be completed at different stages of the research. As users become more familiar with the checklist, and become aware of the information it compiles, the time required to complete it will likely decrease. In any case, the checklist can serve as a useful repository of essential administrative information, and the time taken to complete the checklist may be considered a worthy investment in ensuring accurate and transparent disclosure of fCOI.

Conclusion

We developed the checklist to help investigators report comprehensive structured information about fCOI to multiple stakeholder groups. We invite comments and suggestions for adaptations and improvement of the next iteration of the checklist at http://www.openmedicine.ca/fcoichecklist. We also call for stakeholder groups to endorse the use of this checklist to improve transparency and mitigate fCOI in clinical research.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter Anderson for technical assistance. We also thank the external experts, listed below, who were collaborators on this project and who provided their valuable insight for our checklist item development.

External experts: Douglas G Altman, DSc, Centre for Statistics in Medicine (Oxford, UK); Alan Cassels, MPA, School of Health Information Sciences, University of Victoria (Victoria, Canada); Padraig Darby, MB, MRCPsych, FRCP(C), Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, University of Toronto (Toronto, Canada); Jocelyn Downie, BA, MA, MLitt, LLB, LLM, SJD, Dalhousie University (Halifax, Canada); Susan Ehringhaus, JD, Association of American Medical Colleges (Washington DC, USA); Laurel Evans, BA, LLB, University of British Columbia (Vancouver, Canada); Davina Ghersi, MPH, PhD, WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (Geneva, Switzerland); David Henry, MBChB, MRCP, FRCP (Edin), Institute for Clinical and Evaluative Sciences (Toronto, Canada); Ron Heslegrave, PhD, University Health Network (Toronto, Canada); Karmela Krleža-Jerić, MD, MSc, DSc, Knowledge Synthesis and Exchange Branch, Knowledge Translation, Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Ottawa, Canada); Christine Laine, MD, MPH, FACP, Annals of Internal Medicine; Ana Marusic, MD, PhD, Croatian Medical Journal, and Council of Science Editors, Zagreb University School of Medicine (Croatia); MM Mello, JD, PhD, Harvard School of Public Health (Boston, USA); Gregory J. Meyer, PhD, Journal of Personality Assessment; Udo Schuklenk, PhD, Queen’s University (Kingston, Canada); Jane Smith, MSc, British Medical Journal; Ross Upshur, MD, MSC, University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics (Toronto, Canada); Margaret A Winker, MD, FACP, Journal of American Medical Association

Research team: An-Wen Chan, MD, DPhil, Women’s College Research Institute, Women’s College Hospital, and Department of Medicine, University of Toronto (Toronto, Canada); Lorraine E Ferris, PhD, LLM, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto; Jennifer Gold, LLB, MPH, Ontario Medical Association (Toronto, Canada); Andrea Gruneir, PhD, Women’s College Research Institute, Women’s College Hospital; John Hoey, MD, Queen’s University (Kingston, Canada); Joel Lexchin, MSc, MD, School of Health Policy and Management, York University (Toronto, Canada),Emergency Department, University Health Network (Toronto), and Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto; James Maskalyk, MD, Division of Emergency Medicine, University of Toronto; David Moher, PhD, Ottawa Methods Centre, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, and Department of Epidemiology and Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa (Ottawa, Canada); Paula A Rochon,MD, MPH, Women’s College Research Institute, Women’s College Hospital, and Department of Medicine, University of Toronto; David L Streiner, PhD, CPsych, Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto; Nathan Taback, PhD, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto; Marleen Van Laethem, MHSc, Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, and Joint Centre for Bioethics, University of Toronto

Research staff: Peter Anderson, Women’s College Research Institute (Toronto, Canada); Sunila R Kalkar, MBBS MD, MEd, Women’s College Research Institute and Women’s College Hospital (Toronto, Canada); Melanie Sekeres, MSc, Department of Physiology, University of Toronto (Toronto, Canada); Wei Wu, MSc, Women’s College Research Institute, Women’s College Hospital

Biographies

Paula A Rochon, MD, MPH, is senior scientist at Women’s College Research Institute at Women’s College Hospital, Toronto, and professor at the Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

John Hoey, MD, is adjunct professor at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont.

An-Wen Chan, MD, DPhil, is a Phelan scientist at Women’s College Research Institute, Women’s College Hospital, Toronto, and assistant professor at the Department of Medicine, University of Toronto.

Lorraine E Ferris, PhD, LLM, is professor at Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto.

Joel Lexchin, MSc, MD, is professor at the School of Health Policy and Management, York University, Toronto, emergency physician at the Emergency Department, University Health Network, Toronto, and associate professor at the Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto.

Sunila R Kalkar, MBBS MD, MEd, is research coordinator at Women’s College Research Institute and Women’s College Hospital, Toronto.

Melanie Sekeres, MSc, is a graduate student at the Department of Physiology, University of Toronto, Toronto.

Wei Wu, MSc, is statistical analyst at Women’s College Research Institute, Women’s College Hospital, Toronto.

Marleen Van Laethem, MHSc, is research ethicist at the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute, Toronto, and member at the Joint Centre for Bioethics, University of Toronto, Toronto.

Andrea Gruneir, PhD, is a scientist at Women’s College Research Institute, Women’s College Hospital, Toronto.

James Maskalyk, MD, is assistant professor at the Division of Emergency Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto.

David L Streiner, PhD, CPsych, is professor at the Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto.

Jennifer Gold, LLB, MPH, is legal counsel, Ontario Medical Association, Toronto.

Nathan Taback, PhD, is assistant professor at Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto.

David Moher, PhD, is senior scientist at the Ottawa Methods Centre, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, and an associate professor at the Department of Epidemiology & Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ont.

Appendix

Appendix 1.

Interactive PDF Financial Conflicts of Interest Checklist 2010

Footnotes

Competing interests: Joel Lexchin was retained by a law firm representing Apotex to provide expert testimony about the effects of promotion on the sales of medications. He has also been retained as an expert witness by the Canadian federal government in its defence of a lawsuit launched challenging the ban on direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs in Canada. John Hoey and James Maskalyk are associate editors and David Moher is a contributing editor at Open Medicine; none of them was involved in reviewing the article or deciding on its acceptance for publication. No conflicts are reported for the rest of the authors.

Contributors: Paula A Rochon conceived and designed the project, drafted the manuscript and approved it for publication. Joel Lexchin contributed to the conception and design of the checklist, participated in developing the checklist and analyzing the research, and contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript and approved it for publication. Sunila R Kalkar and Wei Wu contributed to the conception and design of the checklist, participated in developing the checklist, performed the data analysis, and contributed to the writing of the final paper and approved it for publication. John Hoey, An-Wen Chan, Lorraine E Ferris, Melanie Sekeres, Marleen Van Laethem, James Maskalyk, David L Streiner, Nathan Taback and David Moher contributed to the conception and design of the checklist, participated in developing the checklist and analyzing the research, and contributed to the writing of the final paper and approved it for publication. Andrea Gruneir participated in analyzing and interpreting the data and revising the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved it for publication. Jennifer Gold was involved in the conception of the checklist, conducted some of the literature reviews, attended the January 2007 meeting, helped develop the checklist, read through the final manuscript and approved it for publication. Paula Rochon is the study guarantor.

References

- 1.Thompson D F. Understanding financial conflicts of interest. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(8):573–576. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199308193290812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lo B, Baldwin WH, Bellini L, Bero L, Campbell E, Childress JF, Corr PB, Dorman T, Grady D, Jost TS, Kelch RP, Krughoff RM, Lowenstein G, Perlmutter J, Powe NR, Thompson DF, Williams DA. In: Conflict of interest in medical research, education, and practice [consensus report] Bernard Lo, Marilyn J Field., editors. National Academy of Sciences; 2009. [accessed 2010 Jan 30]. http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2009/Conflict-of-Interest-in-Medical-Research-Education-and-Practice.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bekelman Justin E, Li Yan, Gross Cary P. Scope and impact of financial conflicts of interest in biomedical research: a systematic review. JAMA. 2003;289(4):454–465. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.4.454. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12533125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals: writing and editing for biomedical publication. 2008. accessed 2009 Dec 4 http://www.icmje.org/2008_urm.pdf. [PubMed]

- 5.National Institutes of Health. Conflict of interest. [accessed 2010 March 14]. http://www.grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/coi/

- 6.Ehringhaus S, Korn D. U.S. medical school policies on individual financial conflicts of interest: results of an AAMC survey. Washington (DC): Association of American Medical Colleges; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals: writing and editing for biomedical publication. 2004 October. accessed 2009 Dec 4 http://www.icmje.org/2004_urm.pdf. [PubMed]

- 8.Moher David, Schulz Kenneth F, Simera Iveta, Altman Douglas G. Guidance for developers of health research reporting guidelines. PLoS Med. 2010 Feb 16;7(2):e1000217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000217. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. International Clinical Trials Registry Platform. The WHO Registry Network. [accessed 2010 Mar 4]. http://www.who.int/ictrp/network/en/

- 10.World Association of Medical Editors Editorial Policy Committee. Authorship. In: Policy statements. 2007. Jul 10, [accessed 2010 Mar 4]. http://www.wame.org/resources/policies#authorship. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drazen Jeffrey M, Van Der Weyden Martin B, Sahni Peush, Rosenberg Jacob, Marusic Ana, Laine Christine, Kotzin Sheldon, Horton Richard, Hébert Paul C, Haug Charlotte, Godlee Fiona, Frizelle Frank A, de Leeuw Peter W, Deangelis Catherine D. Uniform format for disclosure of competing interests in ICMJE journals. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(2):125–126. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-2-200901190-00160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rochon PA, Sekeres M, Lexchin J, Moher D, Wu W, Kalkar SR, et al. Institutional financial conflicts of interest at Canadian academic health science centres: a national survey. Open Med. In press. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Ehringhaus Susan H, Weissman Joel S, Sears Jacqueline L, Goold Susan Dorr, Feibelmann Sandra, Campbell Eric G. Responses of medical schools to institutional conflicts of interest. JAMA. 2008;299(6):665–671. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.6.665. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=18270355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams-Jones B, MacDonald C. Conflict of interest policies at Canadian universities: clarity and content. J Acad Ethics. 2008;6(1):79–90. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D the CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Open Med. 2010;4(1):e60–e68. http://www.openmedicine.ca/article/view/352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.PLoS Medicine Editors. Making sense of non-financial competing interests. PLoS Med. 2008;5(9):e199. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050199. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0050199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]