Abstract

Background

The integrity of the intestinal epithelium is critical for the absorption and retention of fluid and nutrients. The intestinal epithelium also provides a barrier between the intestinal bacteria and the body's immune surveillance. Therefore, intestinal epithelial barrier function is critically important, and disruption of the intestinal epithelium results in rapid repair of the damaged area.

Methods

We evaluated the requirement for protein kinase C iota (PKCι) in intestinal epithelial homeostasis and response to epithelial damage using a well-characterized mouse model of colitis. Mice were analyzed for the clinical, histological and cellular effects of dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) treatment.

Results

Knock out of the mouse PKCι gene (Prkci) in the intestinal epithelium (Prkci KO mice) had no effect on normal colonic homeostasis, however, Prkci KO mice were significantly more sensitive to DSS-induced colitis and death. After withdrawal of DSS, Prkci KO mice exhibited a continued increase in apoptosis, inflammation and damage to the intestinal microvasculature, and a progressive loss of trefoil factor 3 (TFF3) expression, a regulatory peptide important for intestinal wound healing. Knockdown of PKCι expression in HT-29 cells reduced wound healing and TFF3 expression, while addition of exogenous TFF3 restored wound healing in PKCι-depleted cells.

Conclusions

Expression of PKCι in the intestinal epithelium protects against DSS-induced colitis. Our data suggest that PKCι reduces DSS-induced damage by promoting intestinal epithelial wound healing through the control of TFF3 expression.

Keywords: protein kinase C iota, colitis, wound healing, trefoil factor 3, apoptosis, dextran sodium sulfate, permeability

Introduction

The intestinal epithelium forms a physical barrier that separates the luminal contents of the gut from the body's circulation and immune surveillance. Physical disruption of this barrier results in rapid epithelial cell migration to heal the wound in a process called restitution (1). Failure to rapidly heal wounds in the intestinal epithelium results in breach of this barrier by bacteria, promoting activation of the innate immune system. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the intestinal epithelium with clinical symptoms including diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloody stools and weight loss. Histological features of this disease include colonic crypt loss, ulcer formation and infiltration of macrophages and neutrophils. The exact mechanism of initiation and propagation of IBD is unknown and therefore, difficult to treat. IBD is a particularly serious disease, because in addition to pain, discomfort and disruption of normal routine, it is a major risk factor for colon cancer (2). It is therefore important to understand the complex processes that regulate the response to damage to the intestinal epithelium.

An animal model of IBD has been developed that allows analysis of the molecular mechanism(s) of intestinal epithelial cell damage, immune response and healing of the intestinal barrier (3). In this model, dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) is administered to mice orally for several days to induce acute colitis (3, 4). DSS-induced symptoms such as weight loss, intestinal bleeding and shortening of the colon, correlate with pathologic and histologic alterations in the colon (3). DSS mediates direct damage to the intestinal epithelial cells, particularly in the distal colon, resulting in disruption of the intestinal barrier and cytokine production by the intestinal epithelial cells (3). DSS-induced permeability of the intestinal epithelium allows bacterial breach of the mucosal barrier, infiltration of immune cells to the site of injury and release of inflammatory mediators, often resulting in additional damage to the intestinal epithelium (3). The intestinal epithelium rapidly responds to superficial wounds with a process called restitution, which does not require cellular proliferation, in which intestinal epithelial cells migrate to fill the wounded area and re-form an intact barrier (1). Deeper injuries require a more complex process, supported by contributions from non-epithelial cells, in which intestinal epithelial cell restitution is followed by proliferation to repopulate the wounded area and cellular differentiation (1). Epithelial cell restitution heals the damage to the epithelial barrier with subsequent resolution of the elevated inflammation (1). A better understanding of the process of response to intestinal epithelial damage and subsequent recovery will identify new therapeutic targets for treatment of IBD.

Atypical PKCι is expressed in essential all tissues of the body, including the intestinal epithelium (5–8). We have demonstrated a role for PKCι in the initiation and progression of colon cancer (6, 9). PKCι has also been implicated in tight junction formation (10) as well as in the regulation of epithelial barrier integrity (11). Furthermore, atypical PKCs regulate directional migration of epithelial cells (12). In this study, we utilized a well-characterized transgenic mouse line to evaluate the effect of inhibition of PKCι expression in the intestinal epithelium on basal homeostasis and susceptibility to DSS-induced colitis and in vitro wound healing. Genetic knock out of the mouse PKCι gene (Prkci) in the intestinal epithelium (Prkci KO) had no obvious effect on the normal colonic epithelium. However, Prkci KO mice exhibited increased clinical symptoms and histological damage in response to acute DSS treatment. Even after withdrawal of DSS, intestinal inflammation and apoptosis continued to increase in Prkci KO mice, suggesting that intestinal epithelial cells lacking PKCι are less able to heal DSS-induced wounds. In support of this possibility, expression of trefoil factor 3 (TFF3), an intestinal peptide that promotes wound healing and protects against DSS-induced colitis, was significantly repressed in Prkci KO mice recovering from DSS treatment. Depletion of PKCι in HT-29 cells also reduced wound healing and expression of TFF3, whereas addition of exogenous TFF3 reconstituted wound healing in PKCι-depleted colon cancer cells, suggesting that regulation of TFF3 expression is a mechanism by which intestinal epithelial cell PKCι protects against DSS-induced colitis.

Materials and Methods

Prkci KO mice

Floxed Prkci (Prkcif/f) mice (previously called floxed PKC-λ or PKCλfl/fl mice), and cre-mediated knock out of PKCι expression (Prkci KO) in the intestinal epithelium (with Crerecombinase under control of the mouse villin 1 promoter, villin-Cre)(13) have been described previously (9, 14). In all studies, littermates were utilized as controls. Mice were housed in microisolator cages in a pathogen-free barrier facility and maintained at a constant temperature and humidity on a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle. Mice were provided with a standard irradiated rodent chow throughout the experimental protocol and filtered water ad libitum, except as specified for experimental protocols. All of the animal experiments and procedures performed were approved by the Mayo Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Isolation of colon and colonic epithelium

Immediately after CO2 asphyxiation, colons were isolated from cecum to rectum, flushed with cold PBS, measured, and flash frozen for isolation of mRNA. Isolated colon was also fixed in 10% buffered formalin for histological analysis. For evaluation of PKCι mRNA expression, colonic crypts were prepared from freshly isolated colon using a previously described protocol (15).

DSS colitis protocol

3–5 month old mice were administered 3% DSS (MP Biomedical, 36–50 kDa) in the drinking water for 5 days, then returned to normal drinking water until the experimental endpoint. Mice were weighed daily. Both male and female mice were utilized in the DSS colitis protocol. Each gender of mice was distributed evenly between control- and DSS-treated groups. We found no evidence of gender-related differences in DSS-induced colitis, weight loss, proliferation or apoptosis.

Hemoccult analysis

Fecal samples were collected from mice throughout the DSS protocol and analyzed for occult blood using the Hemoccult Sensa paper test strips (Beckmann Coulter, Palo Alto, CA). Test strips were analyzed three days after the samples were isolated, and scored according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Endoscopy and confocal endomicroscopy

Endoscopy was performed using a Karl Storz (Tuttlingen, Germany) endoscope system that includes a rigid telescope with incorporated fiber optic light transmission. Mice remained under isofluorane anesthesia during the entire endoscopy procedure. Saline solution was flushed into the colon to clear feces for endoscopic imaging. Probe-based confocal endomicroscopy was performed using a Cellvizio LAB Fluorescence imaging system (VisualSonics, Ontario, Canada) and Angio-SPARK™ 680-IVM nanoparticles (VisEn Medical, Bedford, MA) excited at 660 nm. The Angio-SPARK™ probe (250 μM, VisEn Medical, Bedford, MA) was administered by retro-orbital injection (100 μl/mouse) immediately before imaging. Images were acquired using both the Karl Storz and VisualSonics ImageCell™ software.

Histological determination of colitis score

Formalin-fixed mouse colon was embedded and sectioned and H&E-stained slides were viewed using an automated image analysis system (Aperio Spectrum, Vista, CA). Colitis score was generated based on a published protocol (4, 16). The colitis score was calculated as the sum of crypt damage, extent and severity of inflammation scores, multiplied by the percent involvement score.

Intestinal permeability

In vivo intestinal permeability was analyzed in mice treated with DSS for 4 days. Four hours prior to sacrifice, mice were administered 0.6mg/g of body weight Fluorescein Isothiocyanate (FITC)-Dextran (4,000 kDa, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) by oral gavage. At the time of euthanasia, serum was collected by cardiac puncture as described previously (17). Serum was analyzed using a fluorescence plate reader (excitation 490 nm, emission 520nm; SpectraMax M5, Molecular Devices, Silicon Valley, CA) and FITC concentrations in the serum were calculated using standard curves generated by serial dilutions of FITC-dextran.

mRNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis

Total RNA was isolated from mouse colon and HT-29 cells using the RNAqueous Isolation Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Isolated mRNA was subjected to qPCR using TaqMan Gene Expression Assay primer and probe sets (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). qPCR analysis was carried out using 10 ng of cDNA on an Applied Biosystems 7900 thermal cycler. Data were evaluated using the SDS 2.3 software package. Data were normalized to glyceraldehyde- 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA abundance to control for RNA concentration. All data are expressed as 2−[CT(target) − CT(GAPDH)].

Analysis of colonic epithelial cell inflammation, apoptosis and proliferation

One hour prior to harvest, mice were injected with 50 μg/kg 5'-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdUrd). Colon sections were stained for infiltrating macrophage (anti-F4/80 as described (18)), cleaved caspase-3 (Cleaved Caspase-3 Asp175, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc) and BrdUrd incorporation. Images of stained slides were captured using the T2 ScanScope console (Aperio Technologies). Apoptosis (cleaved caspase-3) and proliferative (BrdUrd) analysis was performed using an automated thresholding algorithm specific for nuclear staining (provide with the ImageScope analysis software) (17, 19). The apoptotic index was calculated as the ratio of cleaved caspase-3-positive intestinal epithelial cell nuclei to the sum of all epithelial cell nuclei. The proliferative index was calculated for each colon sample as the ratio of BrdUrd-positive intestinal epithelial cell nuclei to the sum of all intestinal epithelial cell nuclei. A minimum of 20,000 intestinal epithelial cell nuclei were analyzed for BrdU incorporation and cleaved caspase-3 staining.

Knock down of human PKCι and TFF3 expression and immunoblot analysis

HT-29 human colon cancer cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection and maintained in a 5% CO2 humidified tissue culture incubator under recommended media conditions. Lentiviral vectors carrying short hairpin RNA interference (RNAi) constructs were generated and used to obtain stable transfectants as described previously (20). The sequences targeted by RNAi constructs are: PKCι: GCCTGGATACAATTAACCATT and TFF3: TGGAGTGCCTTGGTGTTTCAA. PKCι protein expression was determined by immunoblot analysis of total cell lysates.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assessed by MTT assay (CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution, Promega) as recommended by the manufacturer. Cells (3 × 103) were cultured 7 days and analyzed daily for viability on days 3–7.

Proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was assessed using a BrdUrd labeling and detection enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells (3×103 cells/well) were cultured for 24 hours and then assayed for BrdUrd incorporation. Absorbance was measured at 370 and 492 nm with a microplate reader. The OD ratio was calculated for each group and presented relative to NT control (100%) as the effect on proliferation.

Apoptosis assay

Subconfluent HT-29 cells were treated with 3% DSS in complete media for 72 hours. At the end of the treatment period, floating and attached cells were isolated, spun onto a slide and fixed in 2% formalin. Cells were stained with DAPI and analyzed using a fluorescent microscope. Four random areas of the slide were photographed at 20× magnification and apoptotic cells were detected by well-characterized nuclear morphological alterations. Apoptotic index was calculated as the percent apoptotic cells divided by the total DAPI staining cells.

Wound healing

HT-29 cells were plated on 35 mm dishes with 2 mm grid and allowed to grow to confluence. Once cells reached confluence, media was replaced with serum-free media for 24 hours. Confluent cell monolayers were wounded with a pipet tip, washed, and serum-free media replaced. Wounded areas were photographed at time 0 and 24 hours later, and NIH Image J software was used to quantitate the area of wound restitution. In some wound healing assays, purified TFF-3 (21) was included at the time the wound was created until the end of the assay.

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA analysis was used to evaluate the significance of differences between genotypes. Student t-test was used to evaluate the significance of differences in wound healing between different wound healing assays. P<0.05 was considered significant for all analyses.

Results

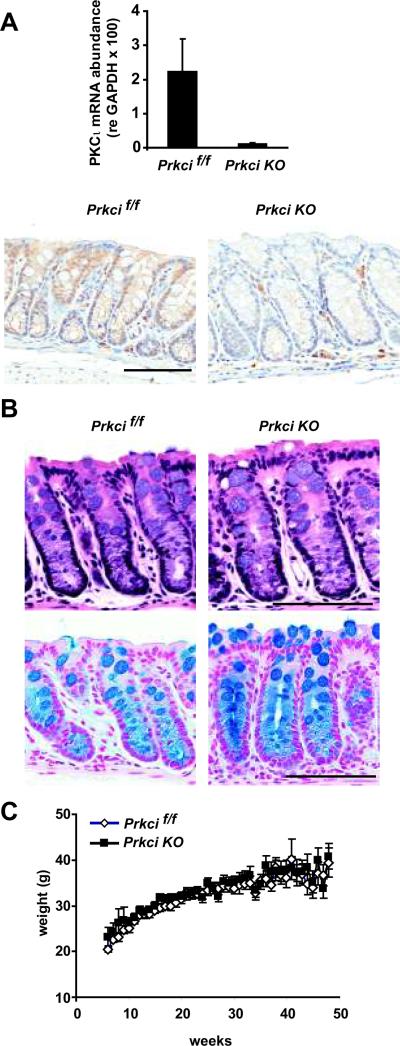

Bi-transgenic Prkcif/f × Vil-cre (Prkci KO) mice, in which the Prkci gene has been disrupted by Cre-mediated excision of the floxed Prkci alleles, expressed significantly less PKCι mRNA and protein in the colonic epithelium compared to Prkcif/f mice in which the Prkci gene is floxed, but not recombined (Figure 1A). Prkci KO mice did not exhibit any obvious differences in colon crypt structure, organization or cellular differentiation, compared to Prkcif/f mice (Figure 1B). Knock out of PKCι in the colonic epithelium had no effect on mouse growth over the first year of life (Figure 1C) or survival (data not shown). These data suggest that PKCι is not required for normal homeostasis or function of the colonic epithelium.

Figure 1. Characterization of PKCι knockout in the colonic epithelium.

A) Top panel: PKCι mRNA abundance was determined by qPCR analysis of mRNA isolated from distal colonic crypts of Prkcif/f and Prkci KO mice. Bars=average±SEM. n=3. Lower panel: Immunohistochemical analysis of PKCι expression in the distal colon of Prkcif/f and Prkci KO mice. Bar=100 μm. B) Knockout of PKCι in the intestinal epithelium does not alter colon crypt morphology or goblet cell distribution. H&E (top) and alcian blue (bottom) staining of Prkcif/f and Prkci KO mouse colon. Bar=100 μm. C) No effect of PKCι knockout in intestinal epithelium on mouse weight gain over one year. For consistency, only weights of male mice are plotted. Bars=average±SEM. n=9–14/group.

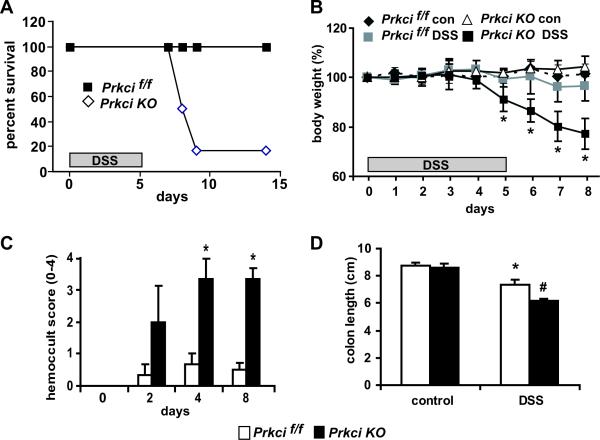

We next evaluated the effect of ablation of PKCι in the colonic epithelium on the response to acute colitis, modeled in mice by DSS-mediated damage to the intestinal epithelium (3). Prkcif/f and Prkci KO mice were administered DSS for 5 days as a 3% solution in the drinking water and then returned to normal drinking water. Our initial observation was a significant decrease in survival of the DSS-treated Prkci KO mice during the recovery period of the DSS protocol (days 6–14) to 17%, compared to 100% survival of Prkcif/f mice on the same treatment protocol (Figure 2A). A closer evaluation of DSS-treated mice over the first eight days of the acute DSS protocol (5 days 3% DSS treatment, followed by 3 days of regular drinking water) revealed that Prkci KO mice lost significantly more weight than Prkcif/f mice on days 6–8, the recovery period of the DSS protocol (Figure 2B). Consistent with this observation, Prkci KO mice exhibited a significant increase in the presence of occult blood, and a significantly greater reduction in colon length (Figure 2C and D).

Figure 2. Prkci KO mice are significantly more sensitive to DSS-induced colitis and death.

Prkcif/f and Prkci KO mice were administered 3% DSS in the drinking water for five days and then returned to normal drinking water. A) Survival curve for Prkcif/f and Prkci KO mice over a 14 day experimental time course. Mice were determined to not survive if they were found dead or euthanasia was deemed necessary by the veterinary staff for humane reasons. n=5,6 mice/group. B) Effect of 3% DSS administration on Prkcif/f and Prkci KO mouse body weight. Bar=average±SEM. n=6, p<0.05. C) Occult blood was analyzed in feces collected from Prkcif/f and Prkci KO mice during the DSS protocol. *p<0.05 vs DSS-treated Prkcif/f mice from the same day. Bar=average±SEM. n=3–6/group. D) Prkcif/f and Prkci KO mice were harvested on day 8 of the DSS protocol and the length of colons assessed. *p<0.05 vs control-treated Prkcif/f mice, #p<0.05 vs control-treated Prkci KO mice and DSS-treated Prkcif/f mice. n=6.

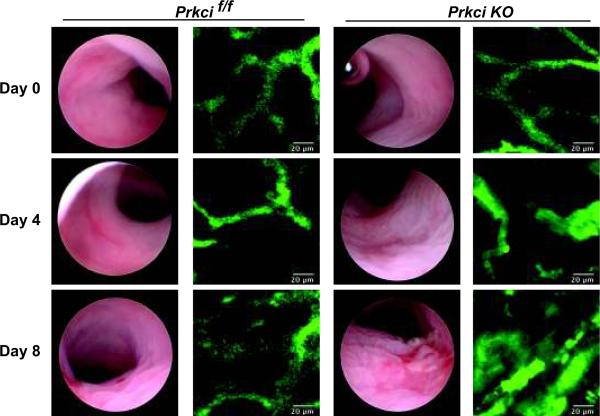

Correlating with the increased clinical signs of colitis, endoscopic analysis revealed macroscopic signs of colitis in DSS-treated Prkci KO mice (Figure 3, day 4) that continued to worsened upon withdrawal of DSS (Figure 3, day 8). In contrast DSS-treated Prkcif/f mice exhibited only mild macroscopic alterations (Figure 3, day 4 and 8). No obvious alterations were observed in the colons of untreated Prkci KO mice (Figure 3, day 0).

Figure 3. Prkci KO mice are significantly more sensitive to DSS-induced macroscopic injury and mucosal vascular alterations.

Prkcif/f and Prkci KO mice were administered 3% DSS in the drinking water for five days and then returned to normal drinking water for an additional three days. Mice were evaluated by endoscopy for signs of macroscopic damage. Mucosal erosions and ulcerations were more prominent in Prkci KO mice than in Prkcif/f mice. The colonic microvasculature was evaluated using confocal endomicroscopy and visualized by AngioSpark™ nanoparticles excited at 660 nm. Prkci KO mice exhibited increased dilation, convolution, and leakage of the microvasculature, corresponding to the increased macroscopic damage.

The pathology of IBD and DSS-induced colitis is accompanied by changes in the microvascular including disruption of the normal capillary network, vessel dilation and leakiness (22, 23). It is now known that the intestinal microvasculature plays an important role in the inflammation and pathogenesis of IBD (reviewed by Danese (24). We therefore evaluated the colonic microvasculature of Prkcif/f and Prkci KO mice throughout the DSS protocol. AngioSpark™ probe, comprised of pegylated fluorescent nanoparticles that remain within the intravascular space for up to 24 hours, was utilized for vascular imaging. Using confocal endomicroscopy to detect the AngioSpark™ nanoparticles, we were able to visualize the mucosal microvasculature (Figure 3), revealing the typical honeycomb structure of the colonic blood vessels (22, 25) in untreated (day 0) Prkcif/f and Prkci KO mice (Figure 3). By day 8 of the DSS protocol, Prkcif/f mice developed some minor leakiness of the microvasculature, while DSS-treated Prkci KO mice exhibited dilation and leakiness of the mucosal blood vessels and a significant loss of the normal microvascular structure (Figure 3) (22), corresponding to the increased macroscopic damage observed in Prkci KO mice (Figure 3).

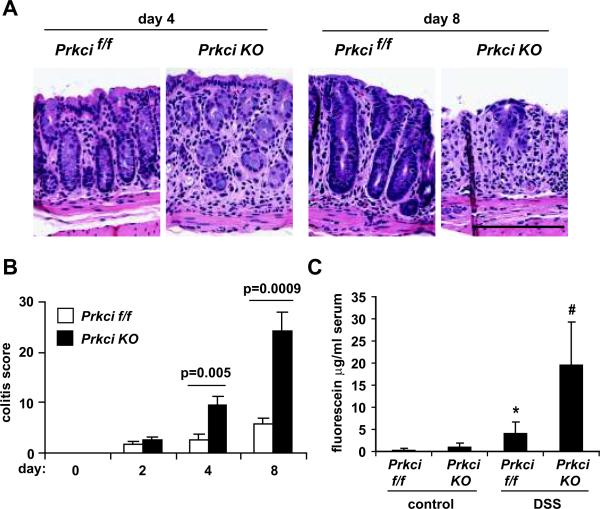

Histological analysis confirmed increased colitis in DSS-treated Prkci KO mice, characterized by increased edema and loss of crypt structure (Figure 4A, day 4). While mild crypt hyperplasia, indicative of epithelial repair, could be observed in the recovering colonic epithelium of Prkcif/f mice, Prkci KO mice exhibited progressive and extensive loss of colonic epithelial cells at this time point (Figure 4A, day 8). Quantitative analysis of the severity of DSS-induced colitis over the experimental time course was performed using a previously validated histological scoring system that assesses inflammation severity, inflammation extent, crypt damage and percent of tissue affected (4). A similar, low level of colitis was detected in both mouse genotypes after 2 days of DSS treatment (Figure 4B), However, the colitis score of DSS-treated Prkci KO mice continued to increase significantly and was dramatically higher than Prkcif/f mice at later time points (Figure 4B). Taken together, these data all demonstrate a significantly higher level of colitis in DSS-treated Prkci KO mice.

Figure 4. Prkci KO mice are more susceptible to DSS-induced damage to the colonic epithelium.

A) Representative H&E stained distal colon sections from mice treated with DSS as described in Figure 3. Bar=100 μm. B) H&E stained distal colon sections were evaluated for crypt damage, extent and severity of inflammation and the overall incidence of damage and a colitis score was calculated (described in Materials and Methods). Bars=average±SEM. n=3–6/group. C) After four days DSS treatment, mice were evaluated for intestinal epithelial permeability, as described in Materials and Methods. Bar=average±SEM. *p=0.05 vs control-treated Prkcif/f mice, #p=0.02 vs control-treated Prkci KO mice and p=0.004 vs DSS-treated Prkcif/f mice. n=3–6/group.

Disruption of the intestinal epithelial barrier is thought to be one of the initial mechanisms by which DSS induces colitis. We therefore evaluated the intestinal epithelial barrier function of DSS- and control-treated Prkci KO and Prkcif/f mice (Figure 4C). Mice were administered FITC-dextran by oral gavage and analyzed 4 hours later for serum FITC. No significant difference in intestinal epithelial barrier function was detected in control-treated Prkci KO and Prkcif/f mice; however, serum FITC levels were significantly higher in Prkci KO mice after 4 days of DSS treatment (Figure 4C), indicating that Prkci KO mice are significantly more sensitive to DSS-induced disruption of the intestinal epithelial barrier.

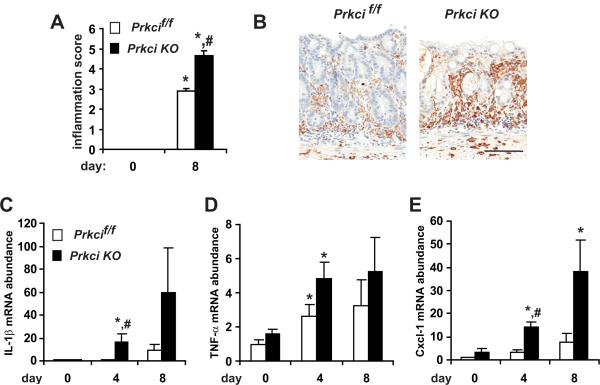

A major pathological feature of IBD is excessive inflammation in the colonic epithelium. The mouse DSS model of IBD is characterized by an inflammatory response in the distal colon (3, 4, 26). H&E staining suggested increased infiltration of inflammatory cells in the colon tissue of DSS-treated Prkci KO mice (Figure 4A). The severity and extent of inflammation are two parameters included in the colitis score presented in Figure 4. Analysis of the inflammation parameters alone reveals a significant increase in the inflammation score of DSS-treated Prkci KO mice (Figure 5A). This observation was confirmed by detection of increased infiltrating macrophages in DSS-treated mice (Figure 5B). The inflammatory response to DSS can also be detected as an increase in inflammatory cytokine mRNA in the distal colon (3, 4, 27). We evaluated expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines known to be induced in the colon by DSS treatment (3). DSS induced IL-1β (Figure 5C) and CXCL1 (also known as KC, Figure 5E) to a significantly higher level in Prkci KO mouse colon, while the expression of TNF-α was induced similarly in both genotypes (Figure 5D). None of the inflammatory cytokines analyzed were significantly elevated in the colons of untreated Prkci KO mice (Figure 5), consistent with a lack of effect of ablation of PKCι on intestinal barrier permeability in the undamaged colon (Figure 4C).

Figure 5. DSS induces significantly more inflammation in Prkci KO mice.

A) DSS-treated Prkci KO mice exhibit a significantly higher inflammation score (sum of inflammation extent and severity) calculated as described in Materials and Methods). B) Increased infiltration of macrophage in DSS-treated Prkci KO mice. Bar=100 μm. C–E) qPCR analysis of mRNA abundance of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the distal colon of Prkcif/f (open bars) and Prkci KO (closed bars) mice treated with DSS as described in Figure 3. C) IL-1β, D) TNF-α and E) CXCL-1 mRNA abundance was normalized to GAPDH and expressed relative to control-treated Prkcif/f mice. Bar=average±SEM. n=5–7/group. *p<0.05 vs control-treated mice of same genotype. #p<0.05 vs same day DSS-treated Prkcif/f mice.

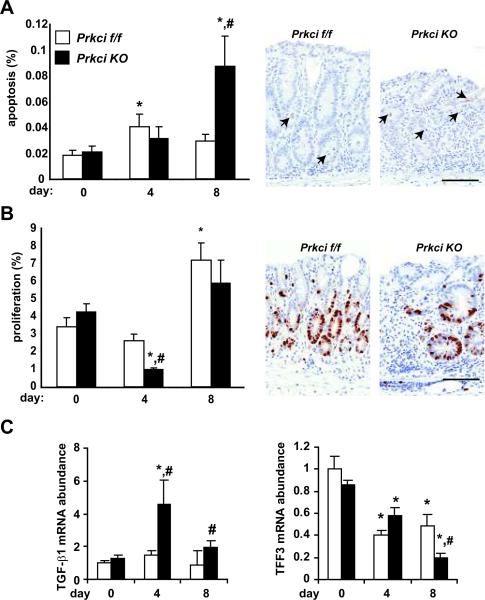

In order to further investigate the mechanism of increased DSS-induced colitis in Prkci KO mice, we evaluated the effect of Prkci knock out on DSS-induced disruption of homeostasis and turnover of the colonic epithelium. DSS-induced apoptosis is thought to be due initially to DSS-induced death of cells of the colonic epithelium, followed by further cell death secondary to the immune response to bacterial infiltration of the wounded intestinal epithelium. We analyzed the level of apoptosis in distal colon intestinal epithelial cells in DSS- and control-treated Prkci KO and Prkcif/f mice, detected by the presence of cleaved caspase-3. As expected, there was no significant difference in the level of apoptosis in untreated Prkci KO and Prkcif/f mice (Figure 6A). DSS treatment resulted in a small increase in apoptosis in the distal colon of both genotypes of mice, but the increase only reached statistically significance in Prkcif/f mice (Figure 6A). During recovery from DSS, the level of apoptosis in the colonic epithelium of DSS-treated Prkcif/f mice returned to near basal levels (Figure 6A). In contrast, apoptosis in the DSS-treated Prkci KO mouse colon increased significantly after withdrawal of DSS, resulting in a dramatically higher level of apoptosis than in the Prkcif/f mice (Figure 6A). These data suggest that the increase in histological damage, fecal blood and colitis score in Prkci KO mice observed on day 4 is probably not due to increased sensitivity to DSS-induced apoptosis. Rather, the high level of colonic epithelial cell apoptosis detected in Prkci KO mice after DSS withdrawal, occurring during what should be the recovery phase, suggests a mechanism involving defective recovery or repair of intestinal injury. It should be noted that the high level of loss of intestinal epithelial cells and the infiltration of inflammatory cells in the DSS-treated colons, particularly in Prkci KO mice, may have affected the accuracy of the measurements of both intestinal epithelial cell proliferation and apoptosis. However, to the extent that our measurements are affected by these factors, the values presented would represent an underestimation of the effect of loss of PKCι.

Figure 6. DSS-treated Prkci KO mice exhibit alterations in DSS-induced colonic epithelial cell apoptosis, proliferation and expression of wound healing peptides.

Prkcif/f (open bars) and Prkci KO (closed bars) mice treated with DSS as described in Figure 3 were evaluated for distal colon epithelial cell A) apoptosis (cleaved caspase-3) and B) proliferation (BrdUrd incorporation) as described in Materials and Methods and C) expression of restitution-promoting peptides. A) Apoptosis is induced in Prkci KO mice after withdrawal from DSS. Bars=mean+/−SEM, n=9–18/group. Representative images of cleaved caspase-3 staining in day 8 colon are shown. Arrows indicate positive-staining cells. Bar=100 μm. B) Epithelial cell proliferation is suppressed in DSS-treated Prkci KO mice. Bars=mean+/−SEM, n=9–15/group. Representative images of BrdU staining in day 8 colon are shown. Bar=100 μm. C) Colonic expression of restitution-promoting peptides in DSS-treated mice. qPCR analysis of mRNA abundance of TGF-β1 (left) and TFF3 (right) in the distal colon. mRNA abundance was normalized to GAPDH and expressed relative to control-treated Prkcif/f mice. Bar=average±SEM. n=6–7/group. *p≤0.05 vs control-treated mice of same genotype; #p<0.05 vs same day DSS-treated Prkcif/f mice

We next investigated the effect of loss of PKCι expression on distal colonic epithelial cell proliferation. No significant difference in basal intestinal epithelial cell proliferation was observed in Prkci KO mice (Figure 6B). DSS treatment significantly decreased colonic epithelial cell proliferation in Prkci KO mice, while the reduction in colonic epithelium proliferation was much less pronounced in Prkcif/f mice (Figure 6B). After withdrawal of DSS, distal colon epithelial cell proliferation increased in both genotypes of mice, and was not significantly different between genotypes (Figure 6B). These data suggest that the Prkci KO mice respond to DSS with an initial suppression of proliferation.

The enhanced and prolonged inflammation and apoptosis observed in Prkci KO mouse colons after withdrawal of DSS suggested that Prkci KO mice may have a wound healing defect that prevents restitution of the DSS-induced damage to the colonic epithelium, allowing continued bacterial infiltration and resulting in a sustained inflammatory response which, in turn, induce additional apoptosis of the colonic epithelium. Many cytokines and growth factors, including TGF-β, promote epithelial cell restitution (1, 28, 29). In many cases, the restitution-enhancing effects of cytokines have been shown to be mediated via modulation of TGF-β expression (29, 30). We therefore measured TGF-β mRNA in the colons of DSS-treated Prkci KO and Prkcif/f mice (Figure 6C, left panel). DSS significantly increased TGF-β mRNA in Prkci KO mouse colon, in contrast to Prkcif/f mice, suggesting that increased sensitivity to DSS-induced colitis observed in Prkci KO mice is not due to a lack of TGF-β.

Trefoil factor 3 (TFF3) is another intestinal peptide implicated in epithelial wound restitution (1, 28, 31, 32). In vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that TFF3 promotes epithelial wound healing and restitution of DSS-damaged intestinal epithelium via a mechanism that is not well understood (33, 34). As previously characterized in human IBD and in DSS-induced colitis in mice (35–37), TFF3 expression decreased with the induction of colitis (Figure 6C, right panel). The DSS-induced decrease in TFF3 was significantly more pronounced in Prkci KO mice after DSS withdrawal (Figure 6C, right panel). These data suggest that reduced TFF3 in the colons of DSS-treated Prkci KO mice may prevent healing of DSS-induced damage to the colonic epithelium.

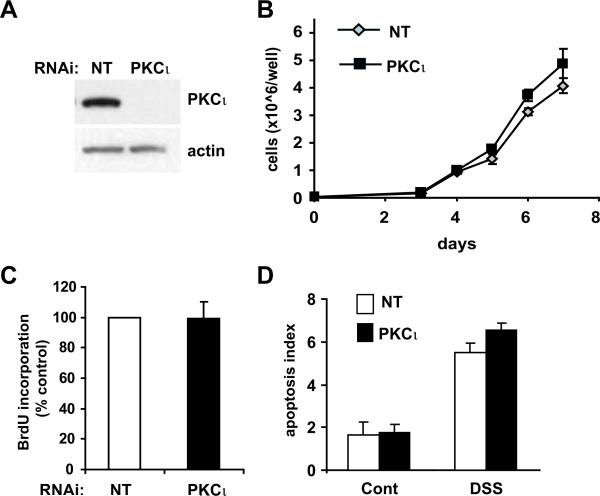

To further investigate the mechanism by which PKCι regulates susceptibility to DSS-induced colitis, we evaluated the requirement for PKCι in HT-29 cell homeostasis and wound healing. Knock down (KD) of PKCι expression was achieved by lenti-viral-mediated expression of a PKCι-directed RNAi construct (Figure 7A). PKCι KD did not reduce HT-29 cell growth or proliferation (Figure 7B and C). Likewise, PKCι KD cells did not increase HT-29 basal apoptosis or sensitivity to DSS-induced apoptosis in vitro (Figure 7D). These data indicate that PKCι does not mediate basal intestinal epithelial cell proliferation or resistance to DSS-induced apoptosis, supporting our in vivo observations.

Figure 7. PKCι KD does not affect cellular proliferation or apoptosis in vitro.

A) Immunoblot analysis of PKCι in HT-29 cells stably expressing either non target (NT) or a PKCι-specific RNAi constructs. Actin expression is shown as a loading control. B) Growth of HT-29 cells stably carrying either NT or PKCι RNAi was determined by MTT colorimetric assay over a 7 day time course. C) Cellular proliferation was assessed by BrdUrd incorporation as described in Materials and Methods. D) PKCι KD does not increase sensitivity to apoptosis. HT-29 cells were exposed to diluent (Cont) or 3% DSS for 72 hours and then assessed for apoptosis as described in Materials and Methods. Experiments were performed in triplicate and are representative of two independent experiments. Mean +/−SEM is plotted.

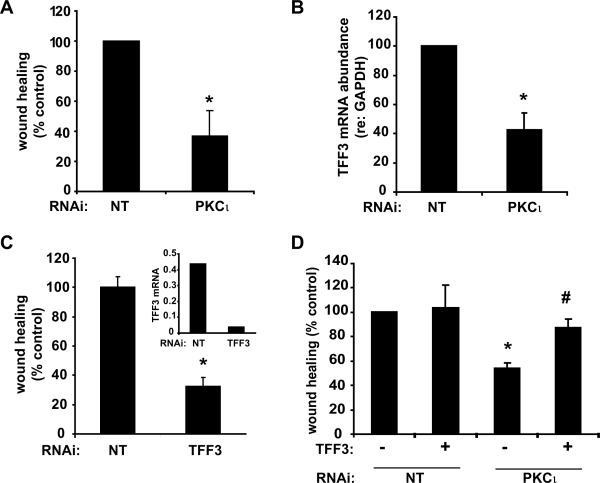

We next investigated the effect of PKCι KD on HT-29 cell wound healing. PKCι KD significantly inhibited healing of a scratch-wounded HT-29 cell monolayer (Figure 8A). PKCι KD cells expressed significantly less TFF3 than HT-29 cells carrying non-targeting RNAi (NT) (Figure 8B), suggesting a mechanism for the reduction in wound healing. To confirm the role of TFF3 in epithelial cell wound healing in vitro, we stably expressed TFF3-directed RNAi in HT-29 cells (Figure 8C, inset). TFF3 KD inhibited HT-29 scratch wound healing (Figure 8C), confirming an important role of TFF3 in wound healing. Significantly, addition of exogenous TFF3 monomer (21) to the culture media reconstituted wound healing in PKCι KD cells (Figure 8D), suggesting that decreased TFF3 expression is responsible for the reduced wound healing in PKCι KD cells. Neither TFF3 RNAi, nor the addition of exogenous TFF3 to the culture media altered the expression of PKCι (data not shown).

Figure 8. PKCι KD inhibits wound healing and TFF3 expressionin vitro.

A) Scratch-wound healing assay of HT-29 cell monolayer was performed as described in Materials and Methods. *p=0.001 versus NT cells, n=6/group. B) qPCR analysis of TFF3 mRNA expression in HT-29 NT and PKCι RNAi cells. n=5, *p=0.01. C) TFF3 KD significantly reduces TFF3 expression and HT-29 scratch-wound healing. Analyses were performed in triplicate and are representative of three independent experiments. Inset: TFF3-targeted RNAi significantly reduces TFF3 mRNA expression. mRNA abundance was normalized to GAPDH expression. Plot is representative of results of two independent experiments. D) Addition of exogenous TFF3 (6.7 ng/ml) to HT-29 scratch-wound healing assay reconstitutes the inhibitory effect of PKCι RNAi. Mean +/−SEM of four independent experiments is plotted. *p=0.004 vs control-treated NT RNAi. #p=0.03 vs control-treated PKCι RNAi.

Discussion

PKCι has been implicated in the establishment and maintenance of intestinal epithelial cell junctions, cell polarity and epidermal barrier formation (10, 38, 39). In this study, we investigated the effect of genetic ablation of PKCι on mouse colonic epithelial integrity, homeostasis and response to damage. Previously, we determined that knock out of PKCι in the small intestinal epithelium had no overt effect on either the morphological organization of the intestinal crypt/villus or the expression and subcellular distribution of β-catenin (9). We now demonstrate that PKCι ablation in the colonic epithelium has no obvious effect on colonic crypt morphology, cytokine gene expression, animal growth or survival. In addition, we observed no effect of Prkci KO on animal weight, colonic epithelial cell homeostasis or basal intestinal epithelial barrier permeability. Because PKCι has been implicated to play a role in the destruction or remodeling of epithelial cell junctions (11), we evaluated the response of Prkci KO mice to DSS-induced colitis. After four days of DSS administration, Prkci KO mice exhibited significantly higher clinical and histological signs of colitis than Prkcif/f mice. However, the level of intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis in Prkci KO mice was similar to Prkcif/f mice at this time point, and proliferation of Prkci KO colonic epithelium was significantly less than in Prkcif/f mice, suggesting that the increased colitis and mortality observed in Prkci KO mice at later time points may be due to a defect in the ability of intestinal epithelial cells to respond to DSS-induced damage. Consistent with this possibility, the difference in colonic inflammation between the genotypes becomes even more pronounced after withdrawal of DSS, during what should be the recovery phase of the DSS protocol. This is likely due to the recruitment of cells of the innate immune system to the site of unrepaired damage to the colonic epithelium and possibly facilitated by increased vascular leakiness (40, 41). Histologically, Prkci KO mice continue to lose colonic epithelial cells after withdrawal of DSS, corresponding to a dramatic increase in epithelial cell apoptosis on day 8. Since the most dramatic differences in clinical symptoms, colitis score and inflammation between Prkci KO and Prkcif/f mice occurred after DSS withdrawal, we hypothesized that Prkci KO mice have a defect in wound healing that results in progressive inflammation and epithelial damage, manifested in precipitous weight loss, fecal blood loss and eventually death.

The intestinal epithelium is constantly subjected to physical, chemical and bacterial insults, which requires rapid restitution to restore the integrity of the intestinal barrier. TGF-β is known to regulate susceptibility to, and to promote restitution of, injury to intestinal epithelial cells (29, 42). However, Prkci KO mice did not appear to have a defect in TGF-β expression, suggesting that the increased damage to the intestinal epithelium of Prkci KO mice was not due to reduced TGF-β expression.

Another factor that regulates intestinal wound healing is trefoil factor 3 (TFF3), also known as intestinal trefoil factor. Unlike other regulatory peptides, which mediate their effects on the basolateral surface of the injured epithelium, TFF3 acts at the apical surface of the intestinal epithelium, through a TGF-β-independent mechanism (28). TFF3 is expressed at a high concentration in the intestine, and is thought to mediate its effects via binding a low affinity receptor that has not yet been indentified (43). Several growth factors that protect against colitis induce TFF3 expression in the intestinal epithelium (4, 36), and TFF3 reduces the severity of DSS-induced colitis in mice (44). TFF3 has been characterized to mediate cell migration, wound healing and promotion of cell survival (34, 45, 46). TFF3 KO mice exhibit normal colonic homeostasis, but these mice are dramatically more sensitive DSS-induced colitis and death (32), a phenotype identical to that described here for Prkci KO mice. DSS-treated Prkci KO mice express reduced TFF3, suggesting the increased DSS-induced injury is due to PKCι regulation of TFF3 expression in the injured epithelium. PKCι KD in HT-29 cells inhibits TFF3 expression and wound healing, but does not sensitize cells to apoptosis, suggesting that the increased damage in vivo is also due to an epithelial wound healing defect. In this mouse model, villin-Cre-mediated knock out of PKCι occurs selective in the intestinal epithelial cells (13). Since PKCι KD in HT-29 cells also inhibits TFF3 expression, this suggests that PKCι regulates TFF3 expression in a cell autonomous manner. Future studies will be required to investigate the mechanism by which PKCι regulates TFF3 expression in intestinal epithelial cells.

The requirement for PKCι for recovery from DSS-induced colitis suggested that PKCι expression may be regulated by DSS exposure. However, we did not detect a significant effect of DSS treatment on PKCι mRNA or protein expression (data not shown). These results indicate that recovery from DSS treatment requires only basal expression of PKCι. Future studies will investigate whether the colonic response to colitis involves alterations in PKCι subcellular localization, protein interactions and/or kinase activity.

In summary, we demonstrate that while ablation of PKCι in the intestinal epithelium has no obvious effect on colonic homeostasis and animal health, loss of PKCι significantly increases susceptibility to DSS-induced colitis and death. The progressively worsening histological damage, inflammation and apoptosis observed in DSS-treated Prkci KO mice upon DSS withdrawal, is consistent with a wound healing defect. DSS-treated Prkci KO mice also expressed significantly less TFF3 in their colons than DSS-treated Prkcif/f mice. PKCι KD in HT-29 cells reduced TFF3 expression and suppressed wound healing in vitro. Exogenous TFF3 recovered in vitro wound healing in PKCι depleted HT-29 cells, suggesting that regulation of TFF3 expression may be a mechanism by which PKCι expression regulates the intestinal epithelial cell wound healing in vitro and in vivo. While regulation of TFF3 expression and intestinal epithelial wound healing is a likely mechanism by which PKCι expression protects against DSS-induced colitis, it is important to emphasize that PKCι may play a role in additional, as yet uncharacterized, signaling pathways in the colonic epithelium that may also contribute to susceptibility to colitis.

Acknowledgements

Grant support: NIH grants CA094122 (N.R. Murray) and CA081436 (A.P. Fields), and The Mayo Clinic Foundation. The authors thank Brandy Edenfield and Justin Weems of the Mayo Clinic, for excellent technical support, Dr. Brian Necela of the Mayo Clinic for expert advice, Dr. Lars Thim of Novo Nordisk A/S for providing the purified, recombinant TFF3, and the Mayo Clinic RNA Interference Technology Resource for RNAi reagents.

Sources of support: NIH grants CA094122 (N.R. Murray) and CA081436 (A.P. Fields), and The Mayo Clinic Foundation.

Abbreviations used

- PKC

protein kinase C

- qPCR

quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction

- BrdUrd

5-bromo-2`-deoxyuridine

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- RNAi

RNA interference

- DSS

dextran sulfate sodium

- TFF3

trefoil factor 3

References

- 1.Sturm A, Dignass AU. Epithelial restitution and wound healing in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:348–353. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Munkholm P. Review article: the incidence and prevalence of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18(Suppl 2):1–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.18.s2.2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yan Y, Kolachala V, Dalmasso G, et al. Temporal and spatial analysis of clinical and molecular parameters in dextran sodium sulfate induced colitis. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams KL, Fuller CR, Dieleman LA, et al. Enhanced survival and mucosal repair after dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in transgenic mice that overexpress growth hormone. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:925–937. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.22470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kovac J, Oster H, Leitges M. Expression of the atypical protein kinase C (aPKC) isoforms iota/lambda and zeta during mouse embryogenesis. Gene Expr Patterns. 2007;7:187–196. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray NR, Jamieson L, Yu W, et al. Protein kinase C{iota} is required for Ras transformation and colon carcinogenesis in vivo. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:797–802. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200311011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wald FA, Oriolo AS, Mashukova A, et al. Atypical protein kinase C (iota) activates ezrin in the apical domain of intestinal epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:644–654. doi: 10.1242/jcs.016246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selbie LA, Schmitz-Peiffer C, Sheng Y, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of PKC iota, an atypical isoform of protein kinase C derived from insulin-secreting cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24296–24302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray NR, Weems J, Braun U, et al. Protein kinase C betaII and PKCiota/lambda: collaborating partners in colon cancer promotion and progression. Cancer Res. 2009;69:656–662. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helfrich I, Schmitz A, Zigrino P, et al. Role of aPKC isoforms and their binding partners Par3 and Par6 in epidermal barrier formation. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:782–791. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banan A, Zhang LJ, Farhadi A, et al. Critical role of the atypical {lambda} isoform of protein kinase C (PKC-{lambda}) in oxidant-induced disruption of the microtubule cytoskeleton and barrier function of intestinal epithelium. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:458–471. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.074591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shin K, Wang Q, Margolis B. PATJ regulates directional migration of mammalian epithelial cells. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:158–164. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madison BB, Dunbar L, Qiao XT, et al. Cis elements of the villin gene control expression in restricted domains of the vertical (crypt) and horizontal (duodenum, cecum) axes of the intestine. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33275–33283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204935200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farese RV, Sajan MP, Yang H, et al. Muscle-specific knockout of PKC-lambda impairs glucose transport and induces metabolic and diabetic syndromes. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2289–2301. doi: 10.1172/JCI31408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su W, Bush CR, Necela BM, et al. Differential expression, distribution, and function of PPAR-gamma in the proximal and distal colon. Physiol Genomics. 2007;30:342–353. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00042.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dieleman LA, Palmen MJ, Akol H, et al. Chronic experimental colitis induced by dextran sulphate sodium (DSS) is characterized by Th1 and Th2 cytokines. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;114:385–391. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00728.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fields AP, Calcagno SR, Krishna M, et al. Protein kinase Cbeta is an effective target for chemoprevention of colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1643–1650. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Necela BM, Su W, Thompson EA. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates cross-talk between peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and nuclear factor-kappaB in macrophages. Immunology. 2008;125:344–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02849.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scotti ML, Bamlet W, Smyrk TC, et al. Protein kinase C iota is required for pancreatic cancer cell transformed growth and tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2064–2074. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frederick LA, Matthews JA, Jamieson L, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-10 is a critical effector of protein kinase Ciota-Par6alpha-mediated lung cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:4841–4853. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thim L, Woldike HF, Nielsen PF, et al. Characterization of human and rat intestinal trefoil factor produced in yeast. Biochemistry. 1995;34:4757–4764. doi: 10.1021/bi00014a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLaren WJ, Anikijenko P, Thomas SG, et al. In vivo detection of morphological and microvascular changes of the colon in association with colitis using fiberoptic confocal imaging (FOCI) Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:2424–2433. doi: 10.1023/a:1020631220599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Binstadt BA, Patel PR, Alencar H, et al. Particularities of the vasculature can promote the organ specificity of autoimmune attack. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:284–292. doi: 10.1038/ni1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Danese S. Inflammation and the mucosal microcirculation in inflammatory bowel disease: the ebb and flow. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007;23:384–389. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32810c8de3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ravnic DJ, Konerding MA, Tsuda A, et al. Structural adaptations in the murine colon microcirculation associated with hapten-induced inflammation. Gut. 2007;56:518–523. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.101824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cario E, Gerken G, Podolsky DK. Toll-like receptor 2 controls mucosal inflammation by regulating epithelial barrier function. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1359–1374. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sina C, Arlt A, Gavrilova O, et al. Ablation of gly96/immediate early gene-X1 (gly96/iex-1) aggravates DSS-induced colitis in mice: role for gly96/iex-1 in the regulation of NF-kappaB. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:320–331. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dignass A, Lynch-Devaney K, Kindon H, et al. Trefoil peptides promote epithelial migration through a transforming growth factor beta-independent pathway. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:376–383. doi: 10.1172/JCI117332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dignass AU, Podolsky DK. Cytokine modulation of intestinal epithelial cell restitution: central role of transforming growth factor beta. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1323–1332. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90136-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sturm A, Sudermann T, Schulte KM, et al. Modulation of intestinal epithelial wound healing in vitro and in vivo by lysophosphatidic acid. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:368–377. doi: 10.1053/gast.1999.0029900368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vandenbroucke K, Hans W, Van Huysse J, et al. Active delivery of trefoil factors by genetically modified Lactococcus lactis prevents and heals acute colitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:502–513. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mashimo H, Wu DC, Podolsky DK, et al. Impaired defense of intestinal mucosa in mice lacking intestinal trefoil factor. Science. 1996;274:262–265. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5285.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taupin D, Podolsky DK. Trefoil factors: initiators of mucosal healing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:721–732. doi: 10.1038/nrm1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalabis J, Rosenberg I, Podolsky DK. Vangl1 protein acts as a downstream effector of intestinal trefoil factor (ITF)/TFF3 signaling and regulates wound healing of intestinal epithelium. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6434–6441. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512905200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Podolsky DK, Gerken G, Eyking A, et al. Colitis-associated variant of TLR2 causes impaired mucosal repair because of TFF3 deficiency. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:209–220. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsuura M, Okazaki K, Nishio A, et al. Therapeutic effects of rectal administration of basic fibroblast growth factor on experimental murine colitis. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:975–986. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ciacci C, Di Vizio D, Seth R, et al. Selective reduction of intestinal trefoil factor in untreated coeliac disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;130:526–531. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.02011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suzuki A, Ishiyama C, Hashiba K, et al. aPKC kinase activity is required for the asymmetric differentiation of the premature junctional complex during epithelial cell polarization. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3565–3573. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Izumi Y, Hirose T, Tamai Y, et al. An atypical PKC directly associates and colocalizes at the epithelial tight junction with ASIP, a mammalian homologue of Caenorhabditis elegans polarity protein PAR-3. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:95–106. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang D, Wang H, Brown J, et al. CXCL1 induced by prostaglandin E2 promotes angiogenesis in colorectal cancer. J Exp Med. 2006;203:941–951. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Froicu M, Cantorna MT. Vitamin D and the vitamin D receptor are critical for control of the innate immune response to colonic injury. BMC Immunol. 2007;8:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-8-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beck PL, Rosenberg IM, Xavier RJ, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta mediates intestinal healing and susceptibility to injury in vitro and in vivo through epithelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:597–608. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63853-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chinery R, Cox HM. Immunoprecipitation and characterization of a binding protein specific for the peptide, intestinal trefoil factor. Peptides. 1995;16:749–755. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(95)00045-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kjellev S, Thim L, Pyke C, et al. Cellular localization, binding sites, and pharmacologic effects of TFF3 in experimental colitis in mice. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1050–1059. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9256-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taupin DR, Kinoshita K, Podolsky DK. Intestinal trefoil factor confers colonic epithelial resistance to apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:799–804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu D, el-Hariry I, Karayiannakis AJ, et al. Phosphorylation of beta-catenin and epidermal growth factor receptor by intestinal trefoil factor. Lab Invest. 1997;77:557–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]