Abstract

During landing and cutting, females exhibit greater frontal plane moments at the knee (internal knee adductor moments or external knee abduction moments) and favor use of the knee extensors over the hip extensors to attenuate impact forces when compared to males. However, it is not known when this biomechanical profile emerges. The purpose of this study was to compare landing biomechanics between sexes across maturation levels. One hundred and nineteen male and female soccer players (9–22 years) participated. Subjects were grouped based on maturational development. Lower extremity kinematics and kinetics were obtained during a drop-land task. Dependent variables included the average internal knee adductor moment and sagittal plane knee/hip moment and energy absorption ratios during the deceleration phase of landing. When averaged across maturation levels, females demonstrated greater internal knee adductor moments (0.06±0.03 vs. 0.01±0.02 Nm/kg*m; P<0.005), knee/hip extensor moment ratios (2.0±0.1 vs. 1.4±0.1 Nm/kg*m; P<0.001), and knee/hip energy absorption ratios (2.9±0.1 vs. 1.96±0.1 Nm/kg*m; P<0.001) compared to males. Higher knee adductor moments combined with disproportionate use of knee extensors relative to hip extensors observed in females reflects a biomechanical pattern that increases ACL loading. This biomechanical strategy already was established in pre-pubertal female athletes.

Keywords: knee adductor moment, drop land, energy absorption, maturation

Introduction

When comparing males and females participating in similar sports, females have been reported to have a 3–5 times greater incidence of non-contact ACL injury.(Agel et al. 2005; Messina et al. 1999; Myklebust et al. 1998) The risk for ACL injury has been reported to increase with age and maturation.(Hewett et al. 2007; Michaud et al. 2001) In particular, post-pubertal athletes are thought to be at the greatest risk for ACL injury. (Garrett et al. 2006)

Sex related differences in anatomical, hormonal and neuromuscular factors are thought to contribute to the disproportionate incidence of ACL injury in females. With respect to neuromuscular factors, sex differences in lower extremity biomechanics during the performance of athletic tasks are believed to put females at greater risk for injury than their male counterparts. In general, females exhibit differences in knee mechanics that are thought to increase strain on the ACL. For example, females have been shown to perform landing and cutting tasks with less knee flexion,(Decker et al. 2003; Lephart et al. 2002; Malinzak et al. 2001; McLean et al. 2005; McLean et al. 2004; Salci et al. 2004; Sell et al. 2006; Yu et al. 2005) increased quadriceps activity, (Malinzak et al. 2001; Sigward & Powers 2006) and greater knee extensor moments when compared to males.(Chappell et al.2002; Salci et al. 2004) In addition, females have been shown to exhibit greater knee valgus angles (Ford et al. 2003; Ford et al. 2006; Kernozek et al. 2005; Malinzak et al. 2001; McLean et al. 2004; Salci et al. 2004; Sell et al. 2006; Yu et al. 2005; Pappas et al. 2007; Sell et al. 2006) and knee valgus moments (Chappell et al.2002; McLean et al. 2005; Sigward & Powers 2006) when compared to their male counterparts. Increased frontal plane loading of the knee is of particular concern as it has been reported that and knee abduction angles and external knee abduction moments (ie. internal knee adductor moments) are predictors of ACL injury.(Hewett et al. 2005)

Pollard and colleagues (2010) have reported that the higher knee valgus moments and angles observed in female athletes is reflective of a movement strategy in which there is greater emphasis on knee extensors over hip extensors to decelerate the body center of mass. These authors reported that females who exhibited greater knee valgus angles and moments had lower hip extensor moments and less energy absorption at the hip and higher knee extensor moments and greater energy absorption at the knee during the deceleration phase of a drop-jump task.(Pollard et al. 2010) More specifically, females who exhibited greater knee valgus moments and angles had greater knee to hip extensor moment ratios and higher knee to hip extensor energy absorption ratios compared to females who exhibited smaller knee valgus moments and angles (2.5 vs. 1.5 and 3.5 vs. 2.3, respectively).(Pollard 2010)

Although females differ from males in the performance of sports activities it is not known at what age these biomechanical differences emerge. The development of movement strategies is thought to be influenced by physical maturation. Observable changes in height and weight occur during adolescence, a time period that can span from 9–18 years of age. Concurrent with these changes, increases in muscular strength and strength related performance occur. (Bale et al. 1992; Quatman et al. 2006) During puberty, differences between males and females are magnified as a result of distinct hormonal changes between the sexes. (Beunen & Malina 1988; Roemmich & Rogol 1995; Tanner 1962) It is generally assumed that the growing disparity in strength and performance accounts for the larger proportion of ACL injuries in athletes 14–18 years old. (Griffin et al. 2006) Given that sex differences in skeletal growth, body composition and muscle development occur at the onset of puberty, it is likely that the emergence of sex differences in the performance of sport related activities occurs at this time.

To date, existing research regarding the influence of maturation and sex on lower extremity biomechanics on the performance of athletic tasks is inconsistent(Hewett et al. 2004; Quatman et al. 2006; Swartz et al. 2005; Yu et al. 2005) . Yu and colleagues (2005) reported that kinematic differences between males and females emerge at approximately 12 years and continue to increase with age. However, this study only considered the effects of age without regard to physical maturation. Given that the timing of hormonal and physical changes differs by almost 2 years between males and females and varies considerably within the sexes, (Roemmich & Rogol 1995) stratification of subjects by age provides little insight into the effects of maturation. Two studies that classified subjects by stage of maturation report contradictory results. Hewett and colleagues (2004) reported that sex differences in the knee valgus angle at initial contact of a drop-land task were not evident in pre-pubertal athletes, but emerged in post-pubertal athletes. In contrast, a study comparing pre-pubertal and post-pubertal males and females found that pre-pubertal athletes performed a drop land with smaller hip and knee flexion angles and greater knee valgus when compared to post-pubertal athletes.(Swartz et al. 2005) The disparate findings between the studies of Hewett et al.(2004) and Swartz et al.(2005) may be attributed to differences in the maturational stratification of subjects. Hewett et al. (2004) classified subjects as pre-pubertal, early pubertal or post-pubertal with the average age of the subjects in the post-pubertal group being 15.6 years. In contrast, Swartz and colleagues (2005) only classified subjects as being pre-pubertal or post-pubertal with the average age of subjects in the post-pubertal group being 23.9 years old. Currently, no study has comprehensively evaluated sex differences across all levels of maturation (i.e. pre-pubertal to young adult).

Given the inconsistencies of the previous work in this area, the purpose of the current study was to compare landing biomechanics between male and female soccer athletes across different stages of maturational development. We theorized that sex differences in landing biomechanics would emerge in the post-pubertal group. More specifically, we hypothesized that post-pubertal females would exhibit higher internal knee adductor moments and a greater tendency to use the knee extensors over the hip extensors to attenuate impact forces when compared to post-pubertal males.

Materials and methods

Subjects

One hundred and nineteen soccer players (59 male and 60 females) between the ages of 9 and 22 participated in this study. At the time of recruitment, all subjects were participating in organized soccer at the club or collegiate level. Training schedules typically required athletes at each level to participate in practice or competition 3 to 5 days a week. Subjects had no complaints of lower extremity pain or injury and were excluded from participation if they reported any of the following: 1) history of previous ACL injury or repair, 2) previous injury that resulted in ligamentous laxity at the ankle, hip or knee, or 3) presence of any medical or neurological condition that would impair their ability to perform a landing task.

Subjects were divided into four groups based on their stage of maturational development: pre-pubertal, pubertal, post-pubertal or young adult (Table 1). As stages of pubertal development generally coincide with changes in physical characteristics (Bale 1992) the presence or absence of secondary sex characteristics (i.e. stage of pubic hair development) is generally used to classify pubertal stages. While observational evaluation of these characteristics is considered the gold standard,(Tanner 1962) less intrusive methods of self report have been validated. (Leone & Comtois 2007; Schlossberger et al. 1992; Schmitz et al. 2004) The classification of subjects was based on scores obtained from a self-report of Tanner stages for pubic hair development from figured drawings (Schlossberger et al. 1992; Tanner 1962; Schmitz 2004 et al.) and the modified Pubertal Maturation Observational Scale (PMOS). (Davies & Rose 2000; Davies & Gavin 1997) For improved accuracy, parents assisted participants under the age of 18 in identifying Tanner stage and completing the PMOS. In cases where scores from the PMOS and the Tanner scale did not match, subjects were excluded from the study.

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics (Mean (SD)

| Female | Male | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pre- pubertal (n=15) |

Pubertal (n=15) |

post- pubertal (n=14) |

young adult (n=15) |

pre- pubertal (n=16) |

Pubertal (n=15) |

post- pubertal (n=14) |

young adult (n=15) |

|

| age (yrs) | 10.2 (0.8) | 12.5 (0.7) | 15.7 (1.1) | 19.3 (1.1) | 11.4 (1.0) | 13.3 (1.2) | 15.6 (1.1) | 19.8 (1.4) |

| height (cm) | 144.9(7.2) | 156.6 (6.8) | 166.3 (6.7) | 166.1 (5.7) | 146.9 (8.9) | 160.6 (9.7) | 176.4 (7.4) | 181.5 (7.2) |

| weight (kg) | 37.3 (6.4) | 47.8 (8.9) | 59.7 (6.8) | 64.9(6.9) | 37.9 (5.6) | 52.4 (7.8) | 69.7 (10.2) | 78.0 (6.6) |

For both males and females, a self reported Tanner staging for pubic hair of 1 classified them as pre pubertal, 2–4 as pubertal, and 5 as post-pubertal or young adult. Post-pubertal and young adult groups were further differentiated by age. Participants over the age of 18 (close to or past the age of skeletal maturity) were admitted to the young-adult group.

Tanner stage classification was supported with items identified on the modified Pubertal Maturation Observational Scale (PMOS) (Davies & Rose 2000; Davies & Gavin 1997). The PMOS categorization is based on an unobtrusive observation of 8 secondary sex characteristics such as muscle development, increased perspiration with physical activity, acne, facial or body hair, deepening of the voice, menarche and breast development, in addition to parent report of less obvious characteristics such as growth spurt. Based on the number of items identified on the PMOS questionnaire, subjects were classified as follows: 1 or less: pre-pubertal; 2–5 with growth spurt: pubertal; 6 or greater with growth spurt completed: post-pubertal. A growth spurt was defined as an increase in height 3 to 4 inches in the past year.

Procedures

Testing took place at the Jaquelin Perry Musculoskeletal Biomechanics Research Laboratory at the University of Southern California. All procedures were explained to each subject and informed consent was obtained as approved by the Institutional Review Board for the University of Southern California Health Sciences Campus. Parental consent and youth assent were obtained for all subjects under the age of 18.

Kinematic data were collected using an eight-camera, motion analysis system at a sampling frequency of 250 Hz (Vicon, Oxford Metrics LTD, Oxford, England). Reflective markers (10 mm spheres) placed on specific boney landmarks (see below for details) where used to quantify segment motion. Ground reaction forces were obtained using two AMTI force platforms at a rate of 1500 Hz (Model #OR6-61, Advanced Mechanical Technologies, Inc., Newton, MA, USA).

Reflective markers were placed bilaterally over the following anatomical landmarks: 1st and 5th metatarsal heads, medial and lateral malleoli, medial and lateral femoral epicondyles, greater trochanters, iliac crests, and a single marker on the joint space between the fifth lumbar and the first sacral spinous processes. In addition, reflective markers secured to rigid plates were placed bilaterally on the lateral surfaces of the subject’s thigh, leg and heel counter of the shoe. The rigid plates, iliac crest markers and lumbar marker remained on the subject during testing. All other markers were removed following a static calibration trial. To control for the potential influence of varying footwear, subjects were fitted with same style of cross-training shoe (New Balance Inc., Boston, MA, USA).

Participants performed 4 trials of a drop landing task from a 36 cm platform. Subjects were instructed to drop off the platform and land with their feet on adjacent force plates and to jump as high as they could after landing. Good to excellent within and between day reliability has been established for kinematic and kinetic variables during this task. (Ford et al. 2007) Subjects were not given any verbal cues on landing or jumping technique. Practice trials were permitted to allow subjects to become familiar with the procedures and instrumentation.

Data Reduction

Coordinate data were digitized using Vicon Workstation software and filtered using a fourth-order zero-lag Butterworth 12-Hz low-pass filter. Visual3D™ software (C-Motion, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA) was used to calculate three dimensional knee and hip kinematics and net joint moments. Joint kinematics were calculated using a joint coordinate system approach (Grood et al. 1984). Internal net joint moments were calculated using standard inverse dynamics equations (Bresler 1950), and were normalized to body mass times height. Sagittal plane joint power of the hip and knee was computed as the scalar product of angular velocity and net joint moment. The energy absorbed at the hip and knee was calculated by integrating the respective power-time curves during the deceleration phase of landing.

The landing cycle was identified as the period from foot contact to toe-off as determined by the force plate recordings. For the purposes of this study, only the deceleration phase of the drop land task was examined. The deceleration phase was defined as the period between foot contact to peak knee flexion. Data were obtained from each subjects’ dominant limb (defined as the leg used to kick a ball).

The biomechanical variables of interest included the average knee adductor moment as well as the knee/hip extensor moment ratio and the knee/hip energy absorption ratio during the deceleration phase of the drop land task. The rationale for evaluating the knee adductor moment was based on the work of Hewett et al.(2005) who reported a high external knee abduction moment (equivalent to an internal knee adductor moment) was a predictor of ACL injury. The justification for evaluating the ratio variables was based on the findings of Pollard et al.(2010) who reported that females who exhibited greater knee valgus moments had lower hip extensor moments and less energy absorption at the hip and higher knee extensor moments and greater energy absorption at the knee during the deceleration phase of a drop-jump task.

To examine the relative contributions of the hip and knee to deceleration of the center of mass during landing, the knee and hip extensor moments as well as energy absorbed at these joints were averaged across the deceleration phase. The average knee to hip extensor moment ratio and the average knee to hip energy absorption ratio were then calculated by dividing the respective values at each joint. Using these ratios, a value greater than “1” would indicate a greater contribution of the knee relative to the hip while a value of less than “1” would indicate a greater contribution of the hip relative to the knee. All variables were averaged over the 4 trials.

Statistical Analysis

To assess differences between sexes across maturational stages, two-way ANOVAs (sex × maturation) were performed (P < 0.05). This analysis was repeated for each dependent variable of interest. In the event of a significant main effect of maturation or a significant interaction between sex and maturation, Least Significant Difference (LSD) post-hoc testing was performed. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software (Chicago, IL, USA) and a significance value of P <0.05.

Results

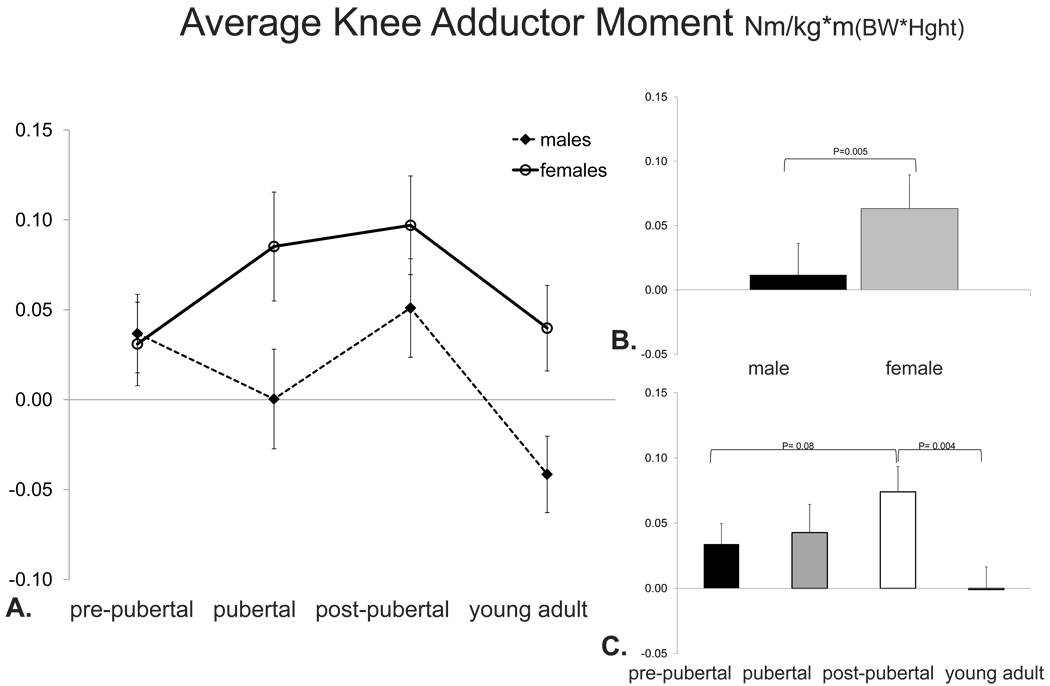

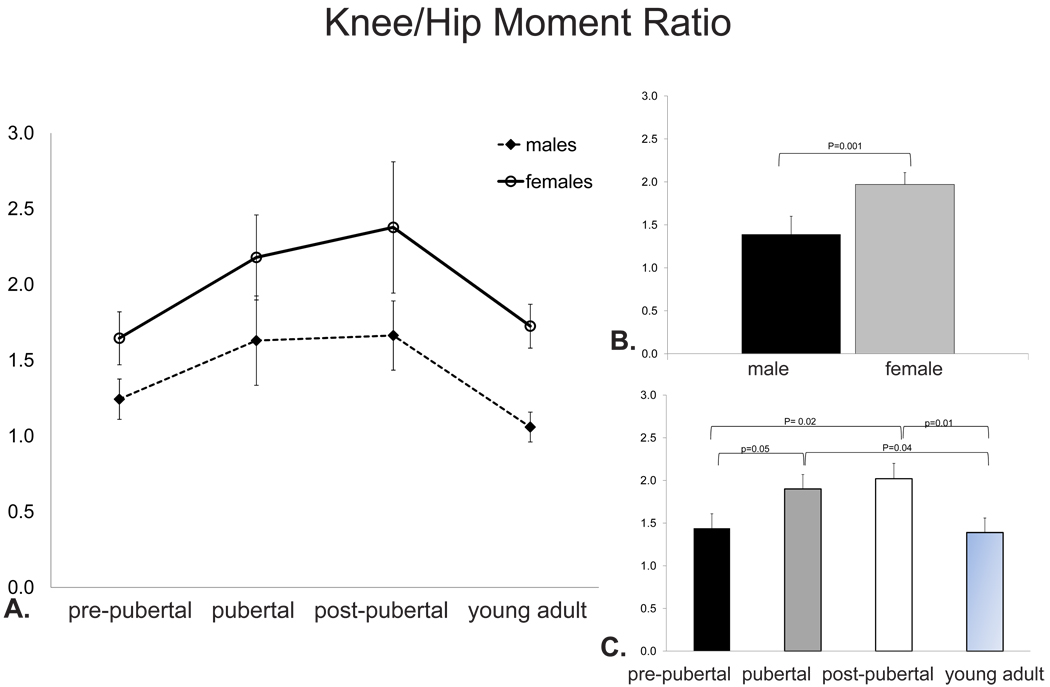

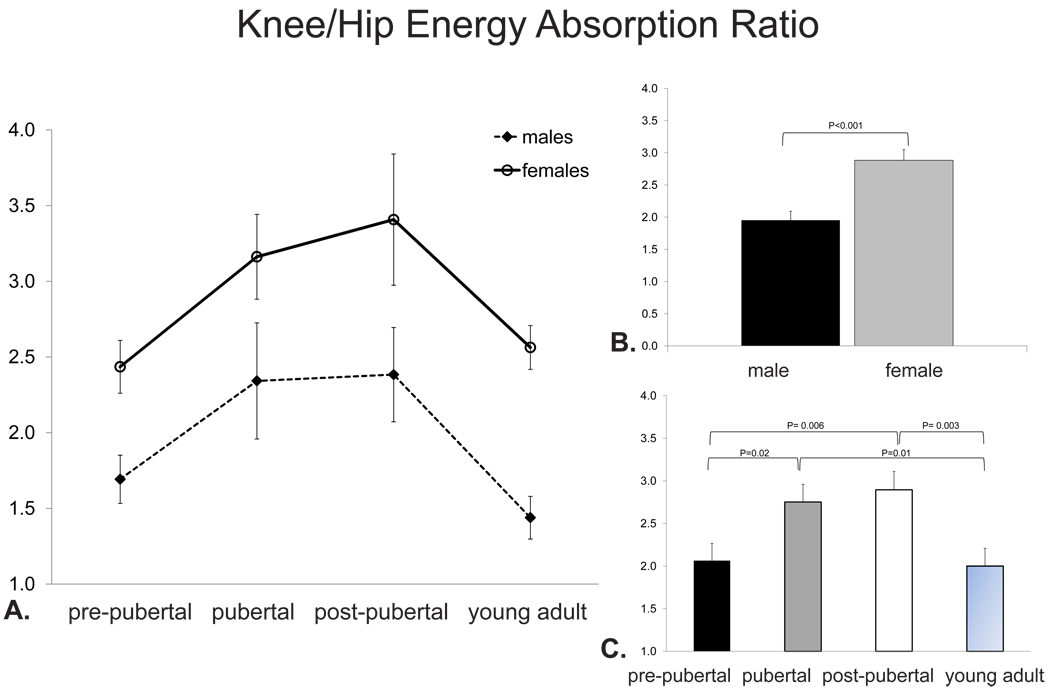

No significant sex × maturation interactions were observed for any of the variables of interest. Significant main effects for sex and maturation were found for the average knee adductor moment (P=0.005, power=0.81 and P=0.04, power=0.67, respectively; Figure 1), knee/hip extensor moment ratio (P=0.001, power=0.92 and P=0.02, power=0.76, respectively; Figure 2), and knee/hip energy absorption ratio (P< 0.001, power=0.99 and P=0.003, power=0.90, respectively; Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Average knee frontal plane moment (Nm/mass*height) A) individual group data stratified by sex and maturation, B) data collapsed across maturation levels, C) data collapsed across sex. Data represents mean ± standard error.

Figure 2.

Knee/hip extensor moment ratio A) individual group data stratified by sex and maturation, B) data collapsed across maturation levels, C) data collapsed across sex. Data represents mean ± standard error.

Figure 3.

Knee/hip energy absorption ratio A) individual group data stratified by sex and maturation, B) data collapsed across maturation levels, C) data collapsed across sex. Data represents mean ± standard error.

When averaged across all maturation groups, females (0.06 ± 0.03 Nm/kg*m) demonstrated significantly greater average knee adductor moments than males (0.01 ± 0.02 Nm/kg*m; P< 0.005; Figure 1B). When averaged across sex, post-pubertal athletes exhibited greater average knee adductor moments (0.074 ± 0.02 Nm/kg*m) than the young adult athletes (−0.001 ± 0.02 Nm/kg*m; P=0.004; Figure 1C). No other group differences were observed.

When averaged across all maturation groups, females demonstrated greater knee/hip extensor moment ratios than males (P=0.001; Figure 2B). When averaged across sex, pubertal athletes had a greater knee/hip extensor moment ratios than the pre-pubertal and young adult athletes (p=0.05 and 0.04, respectively; Figure 2C). In addition, post-pubertal athletes had a larger knee/hip extensor moment ratio than the pre-pubertal and young adult athletes (P=0.02 and 0.01, respectively; Figure 2C). No other group differences were observed.

When averaged across maturation groups, females exhibited significantly greater knee/hip energy absorption ratios compared to males (P< 0.001; Figure 3B) When averaged across sex, pubertal athletes had a larger knee/hip energy absorption ratio than the pre-pubertal and young adult athletes (P=0.02 and 0.01, respectively; Figure 3B). In addition, post-pubertal athletes had a larger knee/hip energy absorption ratio than the pre-pubertal and young adult athletes (P=0.006 and 0.003, respectively; Figure 3C). No other group differences were observed.

Discussion

Consistent with previous literature in this area, the results of the current study indicate that female athletes exhibit a biomechanical profile during landing that is thought to place them at an increased risk for ACL injury. In particular, females exhibited significantly greater knee adductor moments. When averaged across maturation groups, females exhibited average knee adductor moments that were more than 5 times greater than those demonstrated by males. This finding is of concern as the internal knee adductor moment has been shown to be a predictor of ACL injury risk.(Hewett et al. 2005) Our finding of increased internal knee adductor moments in female athletes is consistent with several studies. (Chappell et al. 2002; McLean et al. 2005; Sigward & Powers 2006)

Pollard et al.(2010) have reported that a movement strategy in which there is greater emphasis on knee extensors over hip extensors to decelerate the body center of mass may underlie the higher knee adductor moments observed in females. This premise is supported by the current study in that females exhibited 30% and 32% larger knee/hip moment and energy absorption ratios than males, respectively. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have reported that males tend to engage the hip to a greater extent than females during landing.(Decker et al.2003). Given the importance of the hip extensors in modifying landing stiffness,(DeVita & Skelly 1992) the diminished utilization of the hip musculature in the female group is suggestive of impaired sagittal plane shock absorption. The combined finding of diminished utilization of the hip extensors and higher knee adductor moments in the female athletes may reflect a landing strategy that that relies more on the frontal plane to attenuate impact forces that should ideally be absorbed by the sagittal plane hip musculature.

Contrary to our hypothesis, the sex specific biomechanical profile described above did not emerge post-puberty. In fact, sex differences in landing biomechanics already were present in pre-pubertal athletes. This finding is in contrast to Hewett and colleagues (2004) who found that sex differences in frontal plane angles were not present in pre-pubertal and early pubertal groups, but were evident in the post-pubertal athletes. Our findings do indicate however, that differences between males and females become magnified post-puberty. This was illustrated by the fact that the largest sex differences in the knee/hip extensor moment and energy absorption ratios were evident in the post-pubertal groups (Figures 2–3).

In addition to sex related differences, our data lend support to the theory that biomechanical strategies are influenced by maturation. When averaged across sex, pubertal and post-pubertal athletes had significantly greater knee/hip moment and energy absorption ratios than both the pre-pubertal and young adult athletes. As evident in Figures 2 and 3, the knee to hip sagittal plane moment and energy absorption ratios followed the same trend, increasing from the pre-pubertal group, peaking in the post-pubertal group before returning to pre-pubertal levels in the young adult group. Interestingly, the peak in average knee adductor moments corresponded to the peak in sagittal plane knee to hip moment and energy absorption ratios (Figure 3).

In contrast to previous studies, the current investigation included a maturation group classified as young adult. The addition of this group provided additional insight into changes in performance following puberty, but during a period of more stable growth. During stages of maturation associated with rapid growth (pubertal and post-pubertal) large increases in the knee/hip moment and energy absorption ratios were evident (Figures 2–3). During stages associated with stable growth (pre-pubertal and early adult) the knee/hip moment and energy absorption ratios and knee adductor moments actually were lowest. Interestingly, the pre-pubertal and early adult groups (averaged across sex) did not differ for any variable analyzed. The similarity of pre-pubertal athletes and young adult athletes may be attributed to the fact that the young adult group reached a stable period of growth; however, it also is possible that the young adult group is representative of a group of athletes with good biomechanics who have successfully participated in soccer throughout the developmental years without sustaining a major injury.

Perspectives

The higher knee adductor moments and disproportionate use of the knee extensors relative to the hip extensors observed in females reflects a biomechanical pattern that places greater mechanical loads on the knee joint and ACL. Contrary to our hypothesis, the biomechanical profile exhibited by females did not emerge post-puberty, but instead, was already present in pre-pubertal athletes. Our findings suggest that the implementation of injury prevention strategies should be considered at this stage of maturational development.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01 AR053073-02).

References

- Agel J, Arendt EA, Bershadsky B. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury in National Collegiate Athletic Association Basketball and Soccer: A 13-Year Review. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:524–531. doi: 10.1177/0363546504269937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale P, Mayhew JL, Piper FC, Ball TE, Willman MK. Biological and performance variables in relation to age in male and female adolescent athletes. J Sports MedPhysFitness. 1992;32:142–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beunen G, Malina RM. Growth and physical performance relative to the timing of the adolescent spurt. ExercSport SciRev. 1988;16:503–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresler BF, J P. The forces and moments in the leg during level walking. Transactions of the ASME. 1950;72:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell JD, Yu B, Kirkendall DT, Garrett WE. A comparison of knee kinetics between male and female recreational athletes in stop-jump tasks. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:261–267. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300021901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PL, Gavin WJ. Society for Research in Child Development. Washington D.C: 1997. Convergent validity of two instruments assessing stages of pubertal development. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PL, Rose JD. Motor skills of typically developing adolescents: awkwardness or improvement? PhysOccupTherPediatr. 2000;20:19–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker MJ, Torry MR, Wyland DJ, Sterett WI, Richard Steadman J. Gender differences in lower extremity kinematics, kinetics and energy absorption during landing. Clin Biomech. 2003;18:662–669. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(03)00090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVita P, Skelly WA. Effect of landing stiffness on joint kinetics and energetics in the lower extremity. Med Sci Sports Exer. 1992;24:108–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford KR, Myer GD, Hewett TE. Valgus knee motion during landing in high school female and male basketball players. Med Sci Sport Exer. 2003;35:1745–1750. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000089346.85744.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford KR, Myer GD, Hewett TE. Reliability of landing 3D motion analysis: implications for longitudinal analyses. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:2021–2028. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e318149332d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford KR, Myer GD, Smith RL, Vianello RM, Seiwert SL, Hewett TE. A comparison of dynamic coronal plane excursion between matched male and female athletes when performing single leg landings. Clin Biomech. 2006;21:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett WE, Jr, Swiontkowski MF, Weinstein JN, Callaghan J, Rosier RN, Berry DJ, Harrast J, Derosa GP. the Research Committee of The American Board of Orthopaedic S. American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery Practice of the Orthopaedic Surgeon: Part-II, Certification Examination Case Mix. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:660–667. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin LY, Albohm MJ, Arendt EA, Bahr R, Beynnon BD, DeMaio M, Dick RW, Engebretsen L, Garrett WE, Jr, Hannafin JA, Hewett TE, Huston LJ, Ireland ML, Johnson RJ, Lephart S, Mandelbaum BR, Mann BJ, Marks PH, Marshall SW, Myklebust G, Noyes FR, Powers C, Shields C, Jr, Shultz SJ, Silvers H, Slauterbeck J, Taylor DC, Teitz CC, Wojtys EM, Yu B. Understanding and Preventing Noncontact Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries: A Review of the Hunt Valley II Meeting, January 2005. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1512–1532. doi: 10.1177/0363546506286866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grood ES, Suntay WJ, Noyes FR, Butler DL. Biomechanics of the knee-extension exercise. Effect of cutting the anterior cruciate ligament. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery - American Volume. 1984;66:725–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR. Decrease in Neuromuscular Control About the Knee with Maturation in Female Athletes. J Bone Joint Surg. 2004;86:1601–1608. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200408000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR, Heidt RS, Colosimo AJ, McLean SG, van den Bogert AJ, Paterno MV, Succop P. Biomechanical Measures of Neuromuscular Control and Valgus Loading of the Knee Predict Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Risk in Female Athletes: A Prospective Study. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:492–501. doi: 10.1177/0363546504269591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewett TE, Shultz SJ, Griffin LY, Medicine AOSfS, editors. Understanding and Preventing Noncontact ACL Injuries. Champaign Human Kinetcs; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kernozek TW, Torry MR, H VH, Cowley H, Tanner S. Gender differences in frontal and sagittal plane biomechanics during drop landings. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37:1003–1012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone M, Comtois AS. Validity and reliability of self-assessment of sexual maturity in elite adolescent athletes. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2007;47:361–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lephart S, Ferris C, Riemann B, Myers J, Fu F. Gender differences in strength and lower extremity kinematics during landing. Clin Sport Med. 2002:162–169. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200208000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinzak RA, Colby SM, Kirkendall DT, Yu B, Garrett WE. A comparison of knee joint motion patterns between men and women in selected athletic tasks. Clin Biomech. 2001;16:438–445. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(01)00019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean SG, Huang X, van den Bogert AJ. Association between lower extremity posture at contact and peak knee valgus moment during sidestepping: Implications for ACL injury. Clin Biomech. 2005;20:863–870. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean SG, Lipfert SW, van den Bogert AJ. Effect of gender and defensive opponent on the biomechanics of sidestep cutting. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:1008–1016. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000128180.51443.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina DF, Farney WC, DeLee JC. The incidence of injury in Texas high school basketball. A prospective study among male and female athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:294–299. doi: 10.1177/03635465990270030401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud PA, Renaud A, Narring F. Sports activities related to injuries? A survey among 9–19 year olds in Switzerland. Injury Prevention. 2001;7:41–45. doi: 10.1136/ip.7.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myklebust G, Maehlum S, Holm I, Bahr R. A prospective cohort study of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in elite Norwegian team handball. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1998;8:149–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.1998.tb00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas E, Hagins M, Sheikhzadeh A, Nordin M, Rose D. Biomechanical differences between unilateral and bilateral landings from a jump: Gender differences. Clin J Sport Med. 2007;17:263–268. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e31811f415b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard CD, Sigward SM, Powers CM. Limited hip and knee flexion during landing is associated with increased frontal plane knee motion and moments. Clinical Biomechanics. 2010;25:142–146. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quatman CE, Ford KR, Myer GD, Hewett TE. Maturation Leads to Gender Differences in Landing Force and Vertical Jump Performance: A Longitudinal Study. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2006;34:806–813. doi: 10.1177/0363546505281916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roemmich JN, Rogol AD. Physiology of growth and development. Its relationship to performance in the young athlete. Clin Sport Med. 1995;14:483–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salci Y, Kentel BB, Heycan C, Akin S, Korkusuz F. Comparison of landing maneuvers between male and female college volleyball players. Clin Biomech. 2004;19:622–628. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlossberger NM, Turner RA, Irwin CE., Jr Validity of self-report of pubertal maturation in early adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1992;13:109–113. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(92)90075-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz KE, Hovell MF, Nichols JF, Irvin VL, Keating K, Simon GM, Gehrman C, Jones KL. A validation study of early adolescents' pubertal self-assessments. J Early Adolesc. 2004;24:357–384. [Google Scholar]

- Sell TC, Ferris CM, Abt JP, Tsai Y-S, Myers JB, Fu FH, Lephart SM. The Effect of Direction and Reaction on the Neuromuscular and Biomechanical Characteristics of the Knee During Tasks That Simulate the Noncontact Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Mechanism. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:43–54. doi: 10.1177/0363546505278696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigward SM, Powers CM. The influence of gender on knee kinematics, kinetics and muscle activation patterns during side-step cutting. Clin Biomech. 2006;21:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz EE, Decoster LC, Russell PJ, Croce RV. Effects of Developmental Stage and Sex on Lower Extremity Kinematics and Vertical Ground Reaction Forces During Landing. J Athl Train. 2005;40:9–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner JM. Growth at Adolescence. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Yu B, McClure SB, Onate JA, Guskiewicz KM, Kirkendall DT, Garrett WE. Age and Gender Effects on Lower Extremity Kinematics of Youth Soccer Players in a Stop-Jump Task. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1356–1364. doi: 10.1177/0363546504273049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]