Abstract

Sulfatases are potential therapeutic biopharmaceuticals, as mutations in sulfatase genes leads to inherited disease. Mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS) Type II is caused by mutations in the lysosomal enzyme, iduronate 2-sulfatase (IDS). MPS-II affects the brain and enzyme replacement therapy is ineffective for the brain, because IDS does not cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB). To deliver IDS across the human BBB, the sulfatase has been re-engineered as an IgG-sulfatase fusion protein with a genetically engineered monoclonal antibody (MAb) against the human insulin receptor (HIR). The HIRMAb part of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein acts as a molecular Trojan horse to ferry the fused IDS across the BBB. Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell were stably transfected to produce the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein. The fusion protein was triaged to the lysosomal compartment of MPS-II fibroblasts based on confocal microscopy, and 300 ng/mL medium concentrations normalized IDS enzyme activity in the cells. The HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein was tritiated and injected intravenously into the adult Rhesus monkey at a low dose of 0.1 mg/kg. The IDS enzyme activity in plasma was elevated 10-fold above the endogenous level, and therapeutic plasma concentrations were generated in vivo. The uptake of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein in the brain was sufficiently high to produce therapeutic concentrations of IDS in the brain following IV administration of the fusion protein.

Keywords: iduronate 2-sulfatase, monoclonal antibody, drug delivery, insulin receptor, brain

Introduction

Mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS) Type II (MPS-II), also known as Hunter's syndrome, is an X-linked recessive inborn error of metabolism caused by mutations in the gene encoding the lysosomal enzyme, iduronate-2-sulfatase (IDS) (Wilson et al, 1990). Patients with MPS-II are treated with enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) using recombinant human IDS (Muenzer et al, 2006). However, many patients with MPS-II have brain involvement (Al Sawaf et al, 2008). ERT is not effective in the brain (Wraith et al, 2008), because IDS, like other large molecule biopharmaceuticals, does not cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB). In order to penetrate the brain from blood, protein therapeutics such as IDS must be re-engineered to enable receptor-mediated transport across the BBB (Pardridge, 2008). This is possible with the engineering of an IgG-enzyme fusion protein, wherein the IgG part acts as a molecular Trojan horse (MTH). The IgG is a monoclonal antibody (MAb) against an endogenous BBB receptor, such as the human insulin receptor (HIR), and binding of the HIRMAb to the endogenous BBB insulin receptor triggers receptor-mediated transport across the BBB. The human BBB expresses the insulin receptor (Pardridge et al, 1985), and the BBB insulin receptor mediates the transfer of endogenous insulin from blood into brain (Duffy and Pardridge, 1987). Similarly, the BBB insulin receptor mediates the brain uptake of a peptidomimetic MAb, such as a murine HIRMAb (Pardridge et al, 1995). The HIRMAb has been genetically engineered as either a chimeric or humanized MAb (Boado et al, 2007). Recently, a HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein has been transiently expressed in COS cells (Lu et al, 2010). The COS-derived HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein was shown to retain high IDS enzyme activity and high affinity binding to the HIR. The purpose of the present study was to engineer and clone a line of stably transfected Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells producing the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein, to characterize the purified fusion protein, and to assess the in vivo pharmacokinetics, brain uptake, and IDS enzyme activity following an intravenous (IV) injection in the Rhesus monkey.

Materials and Methods

Engineering of tandem vector and production of CHO line

The cDNA encoding the human IDS cDNA, minus the sequence encoding the signal peptide, was fused to the carboxyl terminus of the CH3 region of the heavy chain (HC) of the chimeric HIRMAb. A tandem vector was engineered in which the expression cassettes encoding this fusion HC, as well as the HIRMAb light chain (LC), and the murine dihydrofolate reductase, were all placed on a single plasmid DNA (Boado et al, 2009a). The 3 expression cassettes spanned 10,107 nucleotides. The light chain was comprised of 234 amino acids (AA), which included a 20 AA signal peptide. The predicted molecular weight of the light chain is 23,398 Da with a predicted isoelectric point (pI) of 5.45. The fusion protein of the HIRMAb heavy chain and IDS was comprised of 989 AA, which included a 19 AA signal peptide. The predicted molecular weight of the heavy chain, without glycosylation, is 108,029 Da with a predicted pI of 6.03. The domains of the fusion heavy chain include a 113 AA variable region of the heavy chain of the HIRMAb, a 330 AA human IgG1 constant region, a 2 AA linker (Ser-Ser), and the 525 AA human IDS.

The tandem vector plasmid DNA was linearized and CHO cells, adapted to serum free medium (SFM), were electroporated with the tandem vector, selected with G418 and hypoxanthine-thymine deficient medium, and amplified with graded increases of methotrexate up to 80 nM. The CHO line underwent 2 successive rounds of 1 cell/well dilutional cloning, and positive clones were selected by measurement of medium human IgG concentrations by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The CHO line was stable through multiple generations, and produced medium IgG levels of 10–20 mg/L in shake flasks at a cell density of 1–2 million cells/mL in SFM.

Purification and analysis of fusion protein

The CHO cells were propagated in 1 L bottles, until 2.4L of conditioned SFM was collected. The medium was ultra-filtered with a 0.2 um Sartopore-2 sterile-filter unit (Sartorius Stedim Biotech, Goettingen, Germany), and applied to a 25 mL protein A Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (GE Life Sciences, Chicago, IL) column equilibrated in 25 mM Tris/25 mM NaCl/5 mM EDTA/pH=7.1. Following application of the sample, the column was washed with 25 mM Tris/1 M NaCl/5 mM EDTA/pH=7.1, and the fusion protein was eluted with 0.1 M sodium acetate/pH=3.7. The acid eluate was pooled, Tris was added to 0.05 M, NaCl was added to 0.15 M, the pH was increased to pH=5.5, and the solution was stored sterile-filtered at 4°C or −70°C.

The identity of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein was verified by human IgG and human IDS Western blotting. For the human IgG Western blot, the primary antibody was a goat anti-human IgG (H+L) (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). For the human IDS Western blot, the primary antibody was a goat anti-human IDS antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). For both blots, the secondary antibody was a biotinylated horse anti-goat IgG antibody (Vector Labs). The purity of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein was verified by reducing and non-reducing sodium dodecylsulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) using a 4–15% gradient gel for the reducing SDS-PAGE and a 7.5% gel for the non-reducing SDS-PAGE. The prestained molecular weight (MW) standards were obtained from Fermentas (Glen Burnie, MD) and from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) for the reducing and non-reducing gels, respectively. Fusion protein purity was also assessed by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) using a high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system. The protein A purified HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein was applied to two 7.8 mm × 30 cm TSK-GEL G3000SWXL columns (Tosoh Bioscience, Tokyo, Japan) in series, under isocratic conditions at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min with a Perkin-Elmer Series 200 pump. The absorbance at 280 nm was detected with a Shimadzu SPD-10A UV-VIS detector and a Shimadzu CR-8 chart recorder. The elution of blue dextran-2000, apoferritin, and alcohol dehydrogenase was measured under the same elution conditions. Sub-visible particles in the final formulation of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein were measured by the light obscuration method (Nelson Labs, Salt Lake City, UT).

The potency of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein was evaluated by measurement of the affinity of binding of the fusion protein to the HIR extracellular domain (ECD), as described previously (Boado et al, 2009a). IDS enzyme activity was measured using a 2-step fluorometric enzymatic assay (Voznyi et al, 2001), as described previously (Lu et al, 2010), at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 1.0 ug/mL. The IDS enzyme substrate, 4-methylumbelliferyl α-L-iduronide-2-sulphate, was purchased from Moscerdam Substrates (Rotterdam, The Netherlands).

HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein uptake by Hunter fibroblasts

Type II MPS Hunter fibroblasts (GM00298) and healthy human fibroblasts (GM00497) were obtained from the Coriell Institute for Medical Research (Camden, NJ), and grown in 6-well cluster dishes to confluency for a dose-response study and a time-response study. For the dose-response study, the medium was aspirated, wells washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and incubated with 1 mL of Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) without serum, along with a range of concentrations of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein, for 2 hours at 37°C. The medium was aspirated, and the wells were washed extensively (1 mL/well, 5 washes) with PBS, and the monolayer was taken up in 0.3 mL/well of lysis buffer (5 mM sodium acetate, 0.2% Triton X-100, pH=4.0), freeze-thawed 4 times, and microfuged for 10 min 4°C. The supernatant was removed for IDS enzyme activity and bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay. The uptake of the fusion protein was expressed as nmol/hr of IDS enzyme activity per mg protein. For the time-response study, the Hunter fibroblasts were incubated with 6 ug/mL of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein for 2 hours, followed by aspiration of the medium and washing of the wells with 1.5 mL SFM 3 times. DMEM plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), without the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein, was then added to the wells, and the cells were incubated at 37°C for 2 to 96 hours. The medium was aspirated, and intracellular IDS enzyme activity was measured as described for the dose-response study.

Confocal microscopy was performed with the Type II MPS Hunter fibroblasts, which were grown overnight in DMEM with 10% FBS to >50% confluency in Lab-Tek chamber slide plates (Thermo Scientific, Rochester, NY). The medium was aspirated, the wells washed well with PBS, and the cells were treated with fresh DMEM with no serum and containing 10 ug/mL of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein. Following a 24 hr incubation at 37°C, the medium was aspirated, the wells washed extensively with cold PBS, and the cells were fixed with 100% cold methanol for 20 min at −20°C. Following a PBS wash, the plates were blocked with 10% donkey serum, and then co-labeled with 10 ug/mL of a goat anti-IDS antibody (R&D Systems), and 10 ug/ml of a mouse MAb to human lysosomal associated membrane protein (LAMP)-1 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Negative control antibodies were the same concentrations of either goat or mouse IgG. The secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were 5 ug/mL each of Alexa Fluor-488 conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (green channel) and Alexa Fluor-594 conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (red channel). The washed slides were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium containing 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Vector Labs). Confocal microscopy was performed with a Leica TCS SP2 AOBS inverted fluorescence microscope with a Leitz P1 Apo 100× oil immersion objective and a Leica confocal laser scanning adapter utilizing argon (476 and 488 nm), new diode (561 nm) and helium-neon (633 nm) lasers, respectively. Optical sections (1 um, resolution 300 nm) were obtained sequentially through the z-plane of each sample.

Rhesus monkey brain uptake and pharmacokinetics

The HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein was radiolabeled with 3H-N-succinimidyl propionate (American Radiolabeled Chemicals, St. Louis, MO) to a specific activity of 1.5 uCi/ug and a trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitability of 99%. The IDS enzyme activity of the [3H]-HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein was measured with the fluorometric enzyme assay and was 64 ± 9 nmol/hr/ug protein. An adult female Rhesus monkey, 4.8 kg, was obtained from Covance (Alice, TX). The animal was injected intravenously (IV) with 828 uCi of [3H]-HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein by bolus injection over 30 seconds in the left femoral vein. The dose of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein was 0.1 mg/kg. The animal was initially anesthetized with intramuscular ketamine, and anesthesia was maintained by 1% isoflurane by inhalation. All procedures were carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as adopted and promulgated by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Following intravenous drug administration, femoral venous plasma was obtained at 1, 2.5, 5, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min for determination of 3H radioactivity. The animal was euthanized, and samples of major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, skeletal muscle, and omental fat) were removed, weighed, and processed for determination of radioactivity. The cranium was opened and the brain was removed. Samples of frontal cortical gray matter, frontal cortical white matter, cerebellar gray matter, cerebellar white matter, and choroid plexus were removed for radioactivity determination.

Samples (~2 gram) of frontal cortex were removed for capillary depletion analysis to confirm transport of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein across the BBB. The capillary depletion method separates the vascular tissue in brain from the post-vascular compartment (Triguero et al, 1990). Based on measurements of the specific activity of brain capillary-specific enzymes, such as γ-glutamyl transpeptidase or alkaline phosphatase, the post-vascular supernatant is >95% depleted of brain vasculature (Triguero et al, 1990). To separate the vascular and post-vascular compartments, the brain was homogenized in 8 mL cold PBS in a tissue grinder. The homogenate was supplemented with 9.4 mL cold 40% dextran (70 kDa, Sigma Chemical Co.), and an aliquot of the homogenate was taken for radioactivity measurement. The homogenate was centrifuged at 3200 g at 4°C for 10 min in a fixed angle rotor. The brain microvasculature quantitatively sediments as the pellet, and the post-vascular supernatant is a measure of capillary depleted brain parenchyma (Triguero et al, 1990). The vascular pellet and supernatant were counted for 3H radioactivity in parallel with the homogenate. The volume of distribution (VD) was determined for each of the 3 fractions from the ratio of total 3H radioactivity in the fraction divided by the total 3H radioactivity in the 120 min terminal plasma. Plasma and tissue samples were analyzed for 3H radioactivity with a liquid scintillation counter (Tricarb 2100TR, Perkin Elmer, Downers Grove, IL). All samples for 3H counting were solubilized in Soluene-350 and counted in Opti-Fluor O (Perkin Elmer).

The 3H adioactivity in plasma, DPM/mL, was converted to % injected dose (ID)/mL, and the %ID/mL was fit to a bi-exponential equation,

The intercepts (A1, A2) and the slopes (k1, k2) were used to compute the median residence time (MRT), the central volume of distribution (Vc), the steady state volume of distribution (Vss), the area under the plasma concentration curve (AUC), and the systemic clearance (CL), as described previously (Pardridge et al, 1995). Non-linear regression analysis used the AR subroutine of the BMDP Statistical Software (Statistical Solutions Ltd, Cork, Ireland). Data were weighted by 1/(%ID/mL)2.

Primate plasma removed at 1 or 120 min after IV injection of the [3H]-HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein was analyzed with gel filtration fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) using a 1 × 30 cm Superose 6HR column (GE Life Sciences, Chicago, IL) and a Perkin-Elmer Series 200 pump. The absorbance at 280 nm was detected with a Shimadzu SPD-10A UV-VIS detector and a Shimadzu CR-8 chart recorder. The elution volume of blue dextran-2000 was used as a measure of the column void volume. The injection sample was comprised of 50 uL of plasma diluted to 200 uL with PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST). The column was eluted at 0.25 mL/min in PBST. Fractions (0.5 mL) were counted for 3H as described above.

Measurement of immunoreactive HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein by ELISA

The concentration of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein in plasma was measured with a 2-site sandwich ELISA, using the HIR ECD as the capture reagent, and an anti-IDS antibody as the detector reagent. The assay was designed so that immunoreactivity would be measured only on the intact HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein, and requires the presence of both parts of the fusion protein, the HIRMAb moiety and the IDS moiety, in order to measure a positive signal. A murine MAb against the HIR (ab36550, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was plated in 96-well plates overnight at 4°C in 0.1 M NaHCO3/8.3 (100 ng/well); this antibody binds an epitope on the HIR that is spatially removed from the HIRMAb binding site. The solution was removed by aspiration, the wells were washed with 0.01 M Tris/0.15 M NaCl/7.4 (TBS) and 100 uL (200 ng)/well of lectin affinity purified HIR ECD was added followed by a 90 min incubation at room temperature (RT). The wells were washed with TBS/0.05% Tween-20 (TBST), and either the primate plasma sample, diluted in PBS, or the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein reference standard, was added in 100 uL/well followed by a 60 min incubation at RT. A goat anti-human IDS antibody (4 ug/mL) was applied in a volume of 100 uL, followed by a 30 min incubation at RT. Following washing with TBST, a conjugate of rabbit anti-goat IgG and alkaline phosphatase (#AP-1000, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) was applied in a volume of 100 uL (500 ng)/well followed by a 45 min incubation at RT. The wells were washed with TBST, and 100 uL/well of p-nitrophenylphosphate (#P5994, Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) was incubated in the dark at RT for 30 min. The color development was terminated by the addition of 100 uL/well of 1.2M NaOH, and color development was measured with an ELISA plate reader at 405 nm. The limit of detection was 1 ng/well of HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein. Assay specificity was demonstrated by showing that high concentrations (10,000 ng/mL) of either the HIRMAb or human IgG1 caused no reaction in the ELISA. The standard curve was determined with 0–1000 ng/mL solutions of HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein and was curvilinear, which was fit with a non-linear regression analysis using the AR subroutine of the BMDP Statistical Software. The blank-corrected absorbance (Abs) was fit to Abs = [(Amax*S)/(EC50 + S)], where S=the concentration of HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein, Amax=the maximal absorbance, and EC50=the concentration of HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein that produces a 50% increase in absorbance.

Results

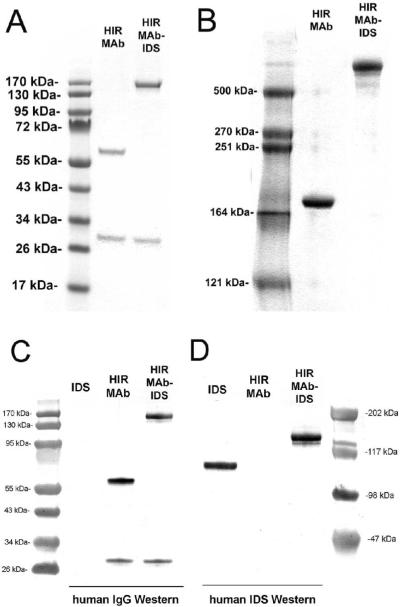

The CHO-derived HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein was purified by protein A to homogeneity on SDS-PAGE (Figure 1). The HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein and the chimeric HIRMAb use the same LC, which migrates with a molecular weight (MW) of 25 kDa, whereas the size of the HC of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein, 143 kDa, is larger than the size of the HC of the HIRMAb, 64 kDa (Figure 1A), owing to fusion of the IDS to the antibody HC. On the non-reducing gel, the HIRMAb migrates at a MW of 176 kDa, whereas the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein migrates as a dimer of 568 kDa (Figure 1B). The HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein also migrates as a dimer on SEC HPLC (Methods). The sub-visible particles in the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein formulation were low, 27 per mL, for particles with a diameter of ≤ 10 um, and 2 per mL, for particles with a diameter of ≤ 25 um. The anti-human IgG antibody reacts with the LC and HC of both the HIRMAb and the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein, but not with human IDS (Figure 1C). The anti-human IDS antibody reacts only with IDS and the HC of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein, but not with the HIRMAb (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

(A) Reducing SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining of the chimeric HIRMAb and the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein. The calculated MW of the light chain is 25 kDa, and the calculated MW of the heavy chain of the HIRMAb and the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein is 64 kDa and 143 kDa, respectively. (B) On the non-reducing gel, the calculated MW of the HIRMAb and the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein is 176 kDa and 568 kDa, respectively. The MWs were calculated from a linear regression of the migration of the MW standards. (C) Western blot with a primary antibody against human IgG. (D) Western blot with a primary antibody against human IDS. The proteins tested are human recombinant IDS, the chimeric HIRMAb, and the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein.

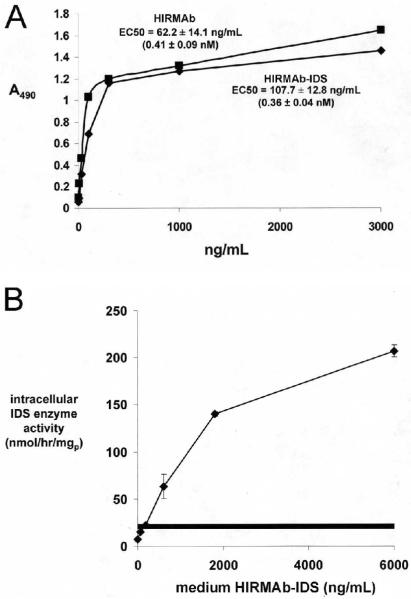

Fusion of IDS to the HC of the HIRMAb does not impair binding to the HIR, as the EC50 of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein binding to the HIR, 0.36 ± 0.04 nM, is equal to the EC50, 0.41 ± 0.09 nM, of the HIRMAb binding to the HIR (Figure 2A). The IDS enzyme specific activity of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein was 63 ± 3 nmol/hr/ug protein, as measured with the fluorometric assay (Methods).

Figure 2.

(A) Binding to the HIR is saturable for the chimeric HIRMAb and the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein. The EC50 was determined by non-linear regression analysis. (B) Intracellular IDS enzyme activity is increased in Hunter fibroblasts in proportion to the concentration of medium HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein. Cells were incubated with fusion protein for 2 hours, washed, and lysed for measurement of intracellular enzyme activity. Data are mean ± SE (n=3 dishes/point). The horizontal bar is the IDS enzyme activity in healthy human fibroblasts (17 ± 2 nmol/hr/mg protein).

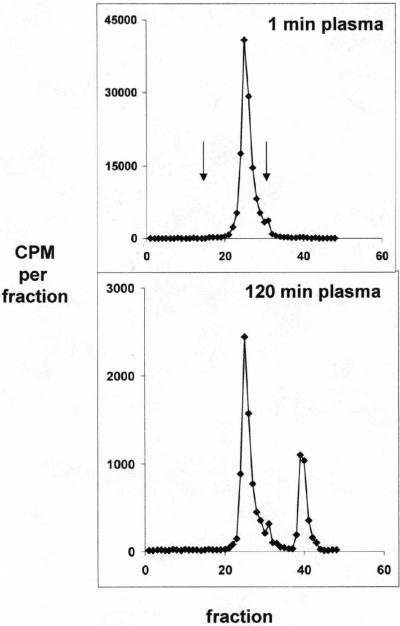

Confocal microscopy of Hunter fibroblasts shows these cells internalize the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein (Figure 3A), and the fusion protein co-localizes with LAMP1, a marker of the lysosomal compartment (Figure 3C). Incubation of Hunter fibroblasts with graded increases in medium HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein for 2 hours results in an increase in intracellular IDS enzyme activity (Figure 2B). A concentration of 300 ng/mL HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein produces an intracellular IDS enzyme activity equal to the IDS activity measured in healthy human fibroblasts, 17 ± 2 nmol/hr/mg protein (Figure 2B). The intracellular IDS enzyme activity in Hunter fibroblasts increased from <5 nmol/hr/mg protein, for the untreated cell, to 140 ± 11 nmol/hr/mg protein after 2 hours of incubation with 6 ug/mL of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein. Following the 2 hour treatment with the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein, the Hunter fibroblasts were washed and incubated further up to 96 hours. The intracellular IDS enzyme activity decayed slowly in the Hunter fibroblasts with a half-time of 3 days (Table I).

Figure 3.

Hunter fibroblasts were incubated with the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein (10 ug/mL) for 24 hours and then fixed with 100% methanol and immune stained for confocal microscopy. The fixed cells were stained with a goat polyclonal antibody to human IDS (panel A: red channel), and a mouse monoclonal antibody to human lysosomal associated membrane protein (LAMP)-1 (panel B: green channel). The overlap image in panel C shows sequestration of the the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein within lysosomes. Panels C and D show the nuclei labeled with DAPI (blue channel). Panel D is an overlap image of negative control primary antibodies.

Table I.

Time-response study of intracellular IDS enzyme activity in Hunter fibroblasts after a 2-hour exposure to the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein

| Time (hours) | Intracellular IDS activity (nmol/hr/mgp) |

|---|---|

| 0 | <5 |

| 2 | 140± 11 |

| 24 | 105 ± 7 |

| 48 | 77 ± 4 |

| 72 | 76 ± 3 |

| 96 | 56 ± 6 |

Mean±SE (n=4 plates/time point). Cells were exposed to the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein (6 ug/mL) in the medium for 2 hours, washed extensively to remove the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein, and incubated up to 96 hours in fresh medium without HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein.

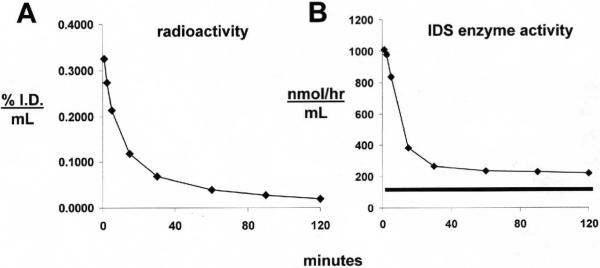

The HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein was tritiated and the [3H]-HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein was injected IV in an adult Rhesus monkey at a low dose of 0.1 mg/kg. The time course of plasma radioactivity is shown in Figure 4A, and these data are expressed as a percent of injected dose (ID)/mL plasma. The percent of total plasma radioactivity that was precipitable by TCA was 99 ± 1%, 99 ± 1%, 99 ± 1%, 99 ± 1%, 99 ± 1%, 90 ± 1%, 80 ± 1%, and 72 ± 1%, respectively at 1, 2.5, 5, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min after IV injection. The plasma radioactivity profile, expressed as %ID/mL, was fit to a 2-exponential equation (Methods) to yield the pharmacokinetics (PK) parameters shown in Table II. The [3H]-the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein is rapidly cleared from blood with a mean residence time of 60 ± 3 minutes, a systemic volume of distribution (Vss) that is double the central compartment volume (Vc), and a high rate of systemic clearance, 2.33 ± 0.04 mL/min/kg (Table II). The plasma IDS enzyme activity was increased 10-fold over the basal value following the IV injection of 0.1 mg/kg HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein, and these data are shown in Figure 4B. The time courses of plasma IDS enzyme activity and plasma radioactive the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein are parallel (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The plasma concentration of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein, expressed as a % of injected dose (ID)/mL plasma (A) and the plasma IDS enzyme activity (B) in the adult Rhesus monkey is plotted against time after a single IV injection of 0.1 mg/kg of the fusion protein. The mean ± SD of plasma IDS enzyme activity in the un-injected Rhesus monkey, 129 ± 2 nmol/hr/mL, is shown by the horizontal bar in panel B.

Table II.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein

| parameter | units | value |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | %ID/mL | 0.253 ± 0.010 |

| A2 | %ID/mL | 0.088 ± 0.006 |

| k1 | min-1 | 0.117 ± 0.010 |

| k2 | min-1 | 0.0131 ± 0.0008 |

| MRT | min | 60 ± 3 |

| Vc | mL/kg | 61 ± 2 |

| Vss | mL/kg | 140 ± 5 |

| AUC|120 | %IDmin/mL | 7.5 ± 0.1 |

| AUCss | %IDmin/mL | 8.9 ± 0.2 |

| CL | mL/min/kg | 2.33 ± 0.04 |

Parameters computed from the plasma profile in Figure 4A.

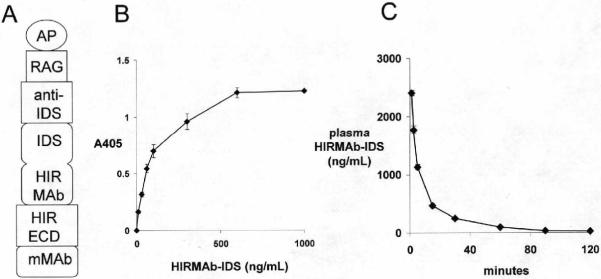

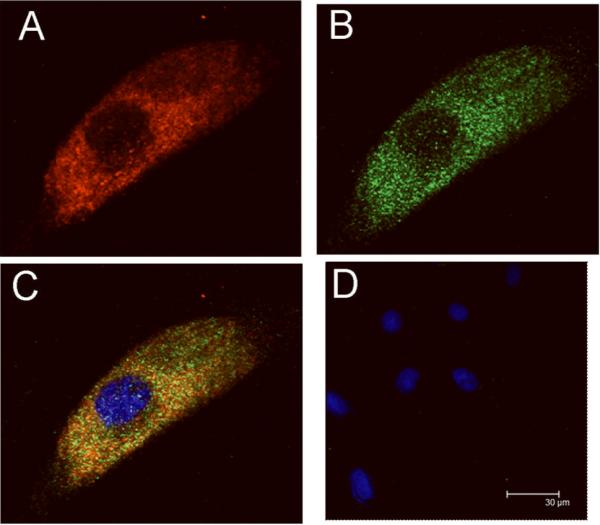

The plasma concentration of immunoreactive the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein was measured with a sandwich ELISA that detects both the HIRMAb and IDS parts of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein (Figure 5A). The standard curve is shown in Figure 5B, which was fit by nonlinear regression (Methods) to convert absorbance signals obtained with monkey plasma into concentrations of immunoreactive HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein, which are shown in Figure 5C. The metabolic stability of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein in vivo was assessed with gel filtration FPLC of primate plasma taken at 1 min (Figure 6, top panel) and 120 min (Figure 6, bottom panel) after IV injection. The plasma radioactivity at 120 min after IV injection is comprised of a major peak, which co-migrates with the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein, and a minor peak that migrates in the salt volume of the column, which correlates with the appearance of TCA-soluble metabolites in plasma at 120 min after injection.

Figure 5.

(A) Design of the 2-site ELISA used to measure the concentration of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein. A mouse monoclonal antibody (mMAb) against the HIR is plated, which captures the HIR ECD derived from CHO cells. The HIRMAb part of the fusion protein binds the HIR ECD, and the IDS part of the fusion protein is bound by a goat anti-IDS antibody, which is bound by a conjugate of a rabbit anti-goat (RAG) antibody and alkaline phosphatase (AP). Both parts of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein, IDS and the HIRMAb, must be intact in order to register a signal in the assay. (B) HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein ELISA standard curve is saturable. The maximal absorbance, Amax, 1.35 ± 0.04, and the EC50, 93.6 ± 9.8, were computed by non-linear regression analysis (Methods). (C) The concentration of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein in primate plasma after a single IV injection of 0.1 mg/kg of fusion protein is plotted vs the time after IV injection.

Figure 6.

Gel filtration elution profile of [3H]-radioactivity in primate plasma removed at 1 min (top panel) and 120 min (bottom panel) after IV injection of [3H]-HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein. In the top panel, the first and second arrows represent the elution volume of blue dextran-2000 and albumin, respectively. The minor peak eluting at fraction 40 in the 120 min profile represents low molecular weight [3H]-metabolites generated from the in vivo metabolism of the [3H]-HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein.

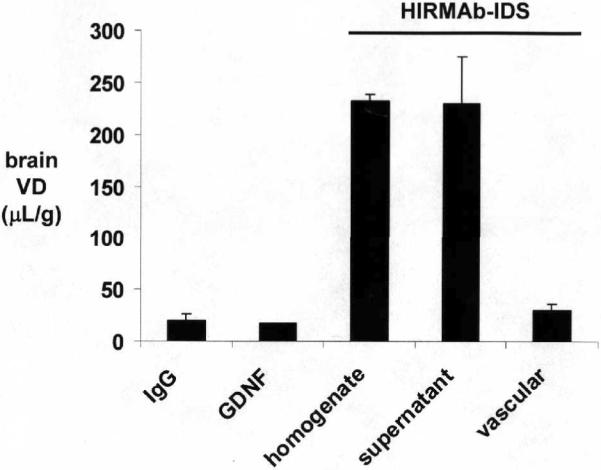

The volume of distribution (VD) of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein in brain homogenate at 2 hours after injection is high, 232 ± 6 uL/gram, compared to the brain VD of a non-specific IgG, 20 ± 6 ul/gram, or the VD, 17 ±1 uL/gram, of a protein, glial derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), that does not cross the BBB (Figure 7). The high brain VD for the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein indicates the fusion protein is either sequestered by the brain vasculature, or has penetrated the BBB and entered brain parenchyma. The VD of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein in the post-vascular supernatant, 230 ± 45 uL/gram, is high compared to the VD of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein in the vascular pellet of brain, 30 ± 7 uL/gram (Figure 7), which indicates that the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein has traversed the BBB and penetrated the brain parenchyma. The VD of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein in the choroid plexus of the primate brain, 637 uL/gram, was high compared to the VD of a non-specific IgG in the Rhesus monkey choroid plexus, which is 139 ± 9 (Pardridge et al, 1995). The organ uptake of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein, expressed as % of injected dose (ID) per 100 gram wet organ weight, in the Rhesus monkey is listed in Table III for brain and peripheral organs. The major organs accounting for the removal of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein from plasma are liver and spleen (Table III).

Figure 7.

The brain homogenate volume of distribution (VD) is shown for 3 proteins: (a) a non-specific IgG, which is a marker of the brain blood volume, (b) GDNF, which is a molecule that does not cross the BBB (Boado and Pardridge, 2009), and (c) the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein. In addition, the brain VD for the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein is shown for the post-vascular supernatant and the vascular pellet in primate brain. Comparison of the VD of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein in the post-vascular supernatant and the vascular pellet shows that 90% of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein taken up by the Rhesus monkey brain has moved through the vascular barrier and penetrated brain parenchyma.

Table III.

Organ uptake of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein in the Rhesus monkey

| organ | Organ uptake (%ID/100 grams) |

|---|---|

| Frontal gray | 0.75 ± 0.01 |

| Frontal white | 0.83 ± 0.07 |

| Cerebellar gray | 0.68 ± 0.08 |

| Cerebellar white | 0.77 ± 0.03 |

| heart | 0.33 ± 0.03 |

| liver | 13.5 ± 3.0 |

| spleen | 13.6 ± 2.5 |

| lung | 0.83 ± 0.29 |

| Skeletal muscle | 0.16 ± 0.03 |

| fat | 0.65 ± 0.13 |

Data are mean ± SE of triplicates samples from one monkey.

Discussion

The results of this study are consistent with the following conclusions. First, a stably transfected CHO line has been cloned that secretes high levels of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein in serum free medium, and that the secreted HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein retains both high IDS enzyme activity and high affinity binding to the HIR with a low nM EC50 (Figure 2A). Second, the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein localizes to the lysosomal compartment (Figure 3), normalizes intracellular IDS activity at a medium concentration of 300 ng/mL (Figure 2B), and has a tissue half-time of 3 days in Hunter fibroblasts (Table I). Third, the PK study shows that the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein is rapidly cleared from blood, and has a high systemic volume of distribution and high plasma clearance rate (Table II). Fourth, a low dose of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein, 0.1 mg/kg IV, produces a plasma IDS enzyme activity that is 10-fold greater than the endogenous enzyme activity (Figure 4B), and produces a plasma concentration of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein (Figure 5C), which normalizes intracellular IDS enzyme activity in target cells (Figure 2B). Fifth, the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein penetrates the BBB of the adult Rhesus monkey, as shown by the high VD in the post-vascular supernatant (Figure 7) with a brain uptake of 0.8% injected dose/100 gram brain (Table III).

Recombinant IDS is used to treat MPS-II (Muenzer et al, 2006). However, the CNS is involved in many patients with MPS-II and enzyme replacement therapy does not treat the brain of MPS-II (Wraith et al, 2008). The failure to treat the brain is due to the lack of transport of IDS across the BBB. The BBB problem is illustrated by measurements of IDS enzyme activity in the plasma and brain compartments following the IV administration of IDS. If the brain/plasma ratio equals the brain blood volume, then the enzyme is confined to the brain plasma volume with no BBB penetration. The brain plasma volume is equal to the brain VD of a non-specific IgG that does not cross the BBB, and this value is 20 uL/gram or 0.020 (Figure 7). Similarly, the brain/plasma ratio of IDS enzyme activity in the mouse at 4 hours after IV injection of human IDS is 0.015 (Polito et al, 2010), which is evidence that IDS does not cross the BBB. In order to produce a form of IDS that can penetrate the brain in MPS-II, human IDS was re-engineered as an IgG-IDS fusion protein (Lu et al, 2010). The HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein is formed by fusion of the 525 amino acid human IDS to the carboxyl terminus of the heavy chain of the chimeric HIRMAb. The HIRMAb binds the insulin receptor on the human BBB, and the Rhesus monkey BBB, and this binding triggers brain penetration of the fusion protein via transport across the endogenous insulin receptor on the BBB (Pardridge et al, 1995).

IDS is a member of a family of sulfatases that requires a post-translational modification to activate enzyme activity (Zito et al, 2005). A cysteine residue in the amino terminal part of the enzyme is converted to N-formyl glycine by sulfatase modifying factor 1 (SUMF1). The IDS enzyme activity of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein, 63 ± 3 nmol/hr/ug protein (Results), is comparable to recombinant IDS (Zareba, 2007). Therefore, the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein secreted by the CHO cell is modified by the endogenous SUMF1 without the requirement for cotransfection of the host cell line with the SUMF1 gene. The HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein is a hetero-tetrameric protein comprised of 2 heavy chains and 2 light chains (Figure 1), and the MW based on amino acid composition, and without glycosylation, is 262,854 Da (Methods). The HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein migrates as a dimer of about 560 kDa in native SDS-PAGE (Figure 1B) and on SEC HPLC (Results). The dimerization of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein is most likely formed by the dimerization of the IDS moiety. Lysosomal enzymes, such as iduronidase (IDUA), exist as dimers in the native state (Ruth et al, 2000). The HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein retains high affinity for the HIR, as shown by the low nM EC50 of binding to the HIR (Figure 2A). The affinity for the HIR of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein is equal to the binding affinity of the HIRMAb without the fused IDS (Figure 2A).

The HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein is triaged to the lysosomal compartment following uptake by Hunter fibroblasts, as demonstrated by confocal microscopy (Figure 3). The intracellular IDS enzyme activity is increased in proportion to the medium concentration of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein, and a medium fusion protein concentration of 300 ng/mL normalizes the intracellular IDS enzyme activity (Figure 3). The intracellular IDS enzyme activity has a tissue half-time of 3 days following a 2 hour exposure of Hunter fibroblasts to the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein (Table I).

The tissue half-time of IDS is likely shorter in vivo than what is observed in cell culture. Following the IV administration of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein in the Rhesus monkey, the fusion protein is rapidly removed from the plasma compartment, based on measurements of radioactivity (Figure 4A), IDS enzyme activity (Figure 4B), or HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein immunoreactivity (Figure 5C). The mean residence time in plasma is 1 hour, and the systemic volume of distribution, Vss, is more than double the central volume of distribution, Vc (Table II). The systemic clearance of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein, 2.3 mL/min/kg (Table II), is high and comparable to the systemic clearance in the Rhesus monkey of the HIRMAb-IDUA fusion protein, 1.1 mL/min/kg (Boado et al, 2008). The peripheral organs accounting for the rapid systemic clearance of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein are primarily liver and spleen, although the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein is taken up by all tissues (Table III). Similarly, HIRMAb systemic clearance in the Rhesus monkey is mediated primarily by liver and spleen (Pardridge et al, 1995). Owing to the rapid clearance in vivo, degradation of a minor fraction of the injected fusion protein is measureable within 2 hours of administration, based on determinations of plasma TCA-soluble radioactivity (Results) or gel filtration FPLC of primate plasma (Figure 7).

The dose of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein administered in this study, 0.1 mg/kg IV, is approximately 10-fold lower than the projected therapeutic dose of 1 mg/kg. Nevertheless, the 0.1 mg/kg dose of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein generates a plasma IDS enzyme activity that is 10-fold greater than the endogenous IDS enzyme activity in the Rhesus monkey (Figure 4B). The 0.1 mg/kg dose of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein produces plasma concentrations of the fusion protein (Figure 5C) that normalize the intracellular IDS enzyme activity in Hunter fibroblasts (Figure 2B). The effect of 0.1 mg/kg HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein on plasma glucose was not measured in this study, as prior work with the HIRMAb-IDUA fusion protein shows no effect on glucose concentration in plasma, urine, or cerebrospinal fluid following the intravenous administration of fusion protein doses ranging from 0.2–20 mg/kg (Boado et al, 2009a).

The reversal of lysosomal storage products in brain requires that the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein undergo net transport through the BBB, as opposed to sequestration by the vascular insulin receptor in brain. The BBB insulin receptor is a transport system for circulating insulin as shown by emulsion autoradiography of brain following systemic administration (Duffy and Pardridge, 1987). The capillary depletion method was developed to demonstrate the net transport of biopharmaceuticals through the BBB and into brain parenchyma (Triguero et al, 1990), and this method has been validated by microscopy of brain. The uptake of the HIRMAb fusion protein by brain cells beyond the BBB was demonstrated in the Rhesus monkey by emulsion and film autoradiography (Boado and Pardridge, 2009). HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein uptake by Rhesus monkey brain was assessed with the capillary depletion method, as shown in Figure 7. The VD of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein in the post-vascular supernatant is higher than the VD in the vascular compartment by nearly 8-fold, which is evidence that the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein penetrates the BBB and enters brain parenchyma. The HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein may then access the intracellular compartment of brain cells via endocytosis mediated by the insulin receptor, which is expressed on brain cells (Zhao et al, 1999). The HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein is then triaged to the lysosomal compartment (Figure 3). The brain uptake of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein, 0.7–0.8 % ID/100 gram brain (Table III), is high compared to the brain uptake of a large molecule that does not cross the BBB in the Rhesus monkey. The brain uptake in the Rhesus monkey of GDNF, which has a comparable plasma AUC as the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein at 2 hours after IV injection, is 0.033 % ID/100 gram brain (Boado and Pardridge, 2009). The brain VD of GDNF is 17 ± 1 uL/gram in the Rhesus monkey, which is equal to the blood volume of brain and indicative of a lack of transport across the BBB (Boado and Pardridge, 2009). Therefore, the brain uptake of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein is >20-fold greater than the uptake expected for a molecule that is confined to the plasma compartment of brain in the Rhesus monkey.

The goal of HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein therapy of the brain in MPS-II is to provide sufficient intracellular IDS enzyme activity so as to deplete the brain cell of lysosomal storage products. While it may not be possible to completely normalize IDS enzyme activity in brain in MPS-II with therapeutic doses of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein, the correction of lysosomal storage products is possible with the exposure of cells to small doses of lysosomal enzyme that are 1–2% of normal enzyme levels (Muenzer and Fisher, 2004). Estimates of the IDS enzyme activity in brain that may be produced with a 1 mg/kg dose of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein is made possible by the data reported in this study. For a 7 kg Rhesus monkey, an HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein injection dose (ID) of 1 mg/kg, an IDS enzyme specific activity of 60,000 units/mg protein, and a brain uptake of 0.8%, the brain IDS enzyme activity is projected to be 3400 units/brain. Given a brain weight of 100 grams in the Rhesus monkey, and 100 mg protein/gram brain, the IDS enzyme activity is projected to be 0.34 units/mg protein. The IDS enzyme activity in the human brain is not known. However, the IDS enzyme activity in mouse brain, as measured with the fluorometric enzyme assay employed in this work, is 2.8 units/mg protein (Tomatsu et al, 2007). Therefore, the 1 mg/kg dose of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein is projected to produce a brain IDS enzyme activity that is 12% of normal levels, assuming the IDS enzyme activity in human and mouse brain is comparable. The therapeutic efficacy of the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein cannot be tested in the mouse, because the HIRMAb part of the fusion protein only cross-reacts with the insulin receptor of Old World primates such as the Rhesus monkey (Pardridge et al, 1995). There is no known MAb against the mouse insulin receptor that can be used as a BBB MTH in the mouse. However, a surrogate BBB MTH has been engineered for the mouse, which is a chimeric MAb against the mouse transferrin receptor (TfR) (Boado et al 2009b). Chimeric TfRMAb fusion proteins have been engineered, which have high rates of penetration of the brain in the mouse (Zhou et al, 2010).

In summary, the present study describes the engineering of a stably transfected CHO line producing the HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein designed to treat the brain in MPS-II. The fusion protein retains both high IDS enzyme activity and high affinity binding to the HIR. The HIRMAb-IDS fusion protein is transported across the BBB in the Rhesus monkey in vivo at rates that are projected to produce therapeutic effects in the brain of MPS-II.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIH grant R43-NS-067707-01. The authors are indebted to Winnie Tai and Phuong Tram for technical support. Confocal laser scanning microscopy was performed at the CNSI Advanced Light Microscopy/Spectroscopy Shared Resource Facility at UCLA, supported with funding from a NIH-NCRR shared resources grant (CJX1-443835-WS-29646) and a NSF Major Research Instrumentation grant (CHE-0722519).

Abbreviations

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- HIR

human insulin receptor

- MAb

monoclonal antibody

- TfR

transferring receptor

- MPS

Mucopolysaccharidosis

- IDS

iduronate 2-sulfatase

- SUMF1

sulfatase modifying factor 1

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- ERT

enzyme replacement therapy

- IV

intravenous

- PK

pharmacokinetics

- MTH

molecular Trojan horse

- HC

heavy chain

- LC

light chain

- AA

amino acid

- SFM

serum free medium

- MW

molecular weight

- ECD

extracellular domain

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- LAMP

lysosomal associated membrane protein

- VD

volume of distribution

- TCA

trichloroacetic acid

- BCA

bicinchoninic acid

References

- Al Sawaf S, Mayatepek E, Hoffmann B. Neurological findings in Hunter disease: pathology and possible therapeutic effects reviewed. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2008;31:473–480. doi: 10.1007/s10545-008-0878-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boado RJ, Zhou QH, Lu JZ, Hui EK, Pardridge WM. Pharmacokinetics and brain uptake of a genetically engineered bifunctional fusion antibody targeting the mouse transferrin receptor. Mol. Pharm. 2010;7:237–244. doi: 10.1021/mp900235k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boado RJ, Pardridge WM. Comparison of blood-brain barrier transport of GDNF and an IgG-GDNF fusion protein in the Rhesus monkey. Drug Metab. Disp. 2009;37:2299–2304. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.028787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boado RJ, Hui EK-W, Lu JZ, Pardridge WM. AGT-181: Expression in CHO cells and pharmacokinetics, safety, and plasma iduronidase enzyme activity in Rhesus monkeys. J. Biotechnol. 2009a;144:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boado RJ, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Pardridge WM. Engineering and expression of a chimeric transferrin receptor monoclonal antibody for blood-brain barrier delivery in the mouse. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009b;102:1251–1258. doi: 10.1002/bit.22135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boado RJ, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Pardridge WM. Humanization of anti-human insulin receptor antibody for drug targeting across the human blood-brain barrier. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2007;96:381–391. doi: 10.1002/bit.21120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boado RJ, Zhang Y, Xia CF, Wang Y, Pardridge WM. Genetic engineering of a lysosomal enzyme fusion protein for targeted delivery across the human blood-brain barrier. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2008;99:475–484. doi: 10.1002/bit.21602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy KR, Pardridge WM. Blood-brain barrier transcytosis of insulin in developing rabbits. Brain Res. 1987;420:32–38. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90236-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu JZ, Hui EK-W, Boado RJ, Pardridge WM. Genetic engineering of a bifunctional IgG fusion protein with iduronate-2-sulfatase. Bioconj. Chem. 2010;21:151–156. doi: 10.1021/bc900382q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muenzer J, Fisher A. Advances in the treatment of mucopolysaccharidosis type I. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350:1932–1934. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muenzer J, Wraith JE, Beck M, Giugliani R, Harmatz P, Eng CM, Vellodi, Martin AR, Ramaswami U, Gucsavas-Calikoglu M, Vijayaraghavan S, Wendt S, Puga AC, Ulbrich B, Shinawi M, Cleary M, Piper D, Conway AM, Kimura A. A phase II/III clinical study of enzyme replacement therapy with idursulfase in mucopolysaccharidosis II (Hunter syndrome) Genet. Med. 2006;8:465–473. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000232477.37660.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardridge WM. Re-engineering biopharmaceuticals for delivery to brain with molecular Trojan horses. Bioconjug. Chem. 2008;19:1327–1338. doi: 10.1021/bc800148t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardridge WM, Eisenberg J, Yang J. Human blood-brain barrier insulin receptor. J. Neurochem. 1985;44:1771–1778. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1985.tb07167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardridge WM, Kang YS, Buciak JL, Yang J. Human insulin receptor monoclonal antibody undergoes high affinity binding to human brain capillaries in vitro and rapid transcytosis through the blood-brain barrier in vivo in the primate. Pharm. Res. 1995;12:807–816. doi: 10.1023/a:1016244500596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polito VA, Abbondante S, Polishchuk RS, Nusco E, Salvia R, Cosma MP. Correction of CNS defects in the MPSII mouse model via systemic enzyme replacement therapy. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:4871–4885. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruth L, Eisenberg D, Neufeld EF. Alpha-L-iduronidase forms semi-crystalline spherulites with amyloid-like properties. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2000;56:524–528. doi: 10.1107/s090744490000007x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomatsu S, Vogler C, Montano AM, Gutierrez M, Oikawa H, Dung VC, Orii T, Noguchi A, Sly WS. Murine model (Galns(tm(C76S)slu)) of MPS IVA with missense mutation at the active site cysteine conserved among sulfatase proteins. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2007;91:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triguero D, Buciak J, Pardridge WM. Capillary depletion method for quantification of blood-brain barrier transport of circulating peptides and plasma proteins. J. Neurochem. 1990;54:1882–1888. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voznyi YV, Keulemans JL, van Diggelen OP. A fluorimetric enzyme assay for the diagnosis of MPS II (Hunter disease) J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2001;24:675–680. doi: 10.1023/a:1012763026526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PJ, Morris CP, Anson DS, Occhiodoro T, Bielicki J, Clements PR, Hopwood JJ. Hunter syndrome: isolation of an iduronate-2-sulfatase cDNA clone and analysis of patient DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1990;87:8531–8535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wraith JE, Scarpa M, Beck M, Bodamer OA, De Meirleir L, Guffon L, Meldgaard Lund A, Malm G, Van der Ploeg AT, Zeman J. Mucopolysaccharidosis type II (Hunter syndrome): a clinical review and recommendations for treatment in the era of enzyme replacement therapy. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2008;167:267–77. doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0635-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zareba G. Idursulfase in Hunter syndrome treatment. Drugs Today (Barc) 2007;43:759–767. doi: 10.1358/dot.2007.43.11.1157619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W, Chen H, Xu H, Moore E, Meiri N, Quon MJ, Alkon DL. Brain insulin receptors and spatial memory. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:34893–34902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zito E, Fraldi A, Pepe S, Annunziata I, Kobinger G, Di Natale PD, Ballabio A, Cosma MP. Sulphatase activities are regulated by the interaction of sulphatase-modifying factor 1 with SUMF2. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:655–660. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]