Abstract

Background

Long-term functional brain effects of adolescent alcohol abuse remain uncertain, partially because of difficulties in distinguishing inherited deficits from neuronal effects of ethanol and by confounds associated with alcohol abuse, especially nicotine exposure. We conducted a longitudinal twin study to determine neurocognitive effects of adolescent alcohol abuse, as measured with the auditory event-related potential (ERP) component P3, a putative marker of genetic vulnerability to alcoholism.

Methods

Twin pairs (N = 177; 150 selected for intrapair concordance/ discordance for alcohol-related problems at age 18½) were recruited from ongoing studies of twins born 1975–1979 in Finland. Alcohol and tobacco use were assessed with questionnaires at ages 16, 17, 18½, and ∼25, and by a structured psychiatric interview concurrent with the ERP testing at mean age 25.8. During ERP recordings, subjects were instructed to detect target tones within a train of frequent “standards” and to ignore occasional “novel” sounds. To distinguish familial factors from ethanol effects, ERP and self-reported alcohol use measures were incorporated into hierarchical multiple regression (HMR) analysis, and intrapair differences in ERP were associated with intrapair differences in alcohol variables.

Results

Novel-sound P3 amplitude correlated negatively with self-reported alcohol use in both between- and within-family analyses. No similar effect was observed for target-tone P3. HMR results suggest that twins' similarity for novel-sound P3 amplitude is modulated by their alcohol use, and this effect of alcohol use is influenced by genetic factors.

Conclusions

Our results, from a large sample of twins selected from a population-based registry for pairwise concordance/discordance for alcohol problems at 18½, demonstrate that adolescent alcohol abuse is associated with subtle neurophysiological changes in attention and orienting. The changes are reflected in decreased novel-sound P3 amplitude and may be modified by genetic factors.

Keywords: Adolescents, Alcohol Abuse, Event-Related Potentials, P3, Twin Study

Longitudinal Functional Brain effects resulting from adolescent alcohol abuse are difficult to definitively document. But there is evidence that the adolescent brain may be more vulnerable to the effects of addictive substances, because extensive neuromaturational processes are occurring during this developmental period (Clark et al., 2008; Lubman et al., 2007). Brain constituents actively developing during adolescence include the prefrontal cortex, limbic system areas, and white matter myelin. Deficits or developmental delays in these structures and their functions are suggestive of disrupted developmental trajectories in early-onset substance users, although there is growing evidence that high-risk youths have premorbid neurobiological vulnerabilities (Clark et al., 2008; Lubman et al., 2007). One magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study of adolescent-onset alcohol users suggested that the total hippocampal volume correlates positively with the age at onset and negatively with the duration of the alcohol use disorder (De Bellis et al., 2000). Another MRI study (De Bellis et al., 2005) found a smaller prefrontal cortex associated with early-onset drinking. Genetic factors contribute to individual differences in trajectories of adolescent drinking (Jackson et al., 2009; Madden et al., 2000; McGue et al., 2001; Rose et al., 2001; Viken et al., 2007) to the development of adolescent-onset alcohol disorders (Pagan et al., 2006) and to neurophysiological abnormalities in adolescents at elevated risk for alcoholism (Begleiter et al., 1984; Hill et al., 2000, 2001). Early initiation of alcohol use is robustly predictive of later alcoholism disorder (DeWit et al., 2000) and to certain attentional deficits observed in adult alcoholics (Ahveninen et al., 2000). Grant and colleagues (2006) found that the genetic factors influencing early-onset regular drinking also contribute to later alcohol dependence and drug abuse, but the association was not entirely explained by shared genes (nor by shared family environments).

Effects of alcohol on brain function can be studied by using auditory event-related potentials (ERPs), stimulus-averaged electroencephalogram (EEG) epochs. The ERP component P3, elicited by targets or by unexpected “deviants” embedded within a train of repetitive nontarget stimuli, has been employed extensively in alcohol research. Both auditory and visual studies suggest that P3 is reduced and/ or delayed in chronic alcoholics (Porjesz and Begleiter, 1997). But the interpretation of such evidence is uncertain: previous family (Begleiter et al., 1987; Patterson et al., 1987; Perlman et al., 2009; Pfefferbaum et al., 1991) and twin studies (Carlson et al., 2002; Perlman et al., 2009; Yoon et al., 2006) suggest that these P3 phenomena could be genetic markers of vulnerability to alcohol abuse, rather than consequences of it. That interpretation is supported by evidence (Almasy et al., 1999; Katsanis et al., 2007; O'Connor et al., 1994; Wright et al., 2001) that P3 amplitude is moderately heritable, with heritability estimates ranging from 39 to 79%, and by analogous evidence of inheritance of P3 latency (Almasy et al., 1999; Polich and Burns, 1987; Rogers and Deary, 1991). A meta-analysis by van Beijsterveldt and van Baal (2002) found meta-heritability estimates of 60% for P3 amplitude and 51% for P3 latency. And longitudinal twin studies demonstrate familial factors substantially contribute to the age-to-age phenotypic stability of P3 across 18 months of adolescence (van Beijsterveldt et al., 2001).

P3 consists of 2 major subcomponents: novel-sound P3 (P3a), a subcomponent thought to be associated with involuntary attention switching to stimulus changes (Escera et al., 2000), with further study suggesting it is a complex signal that comprises alerting, orienting, and executive control processes triggered by an unexpected stimulus (SanMiguel et al., 2010). P3a is thought to originate from frontal areas where stimulus-driven disruption of attention arouses activation related to dopaminergic processes (Polich, 2007; Polich and Criado, 2006). Target-tone P3 (P3b), the other subcomponent, putatively reflects conscious stimulus evaluation, target detection, and working memory functions, and is thought to originate from temporal-parietal activity related to norepinephrine processes (Polich, 2007; Polich and Criado, 2006; Polich and Herbst, 2000). Both P3a and P3b are diminished and delayed in chronic alcoholics (Hada et al., 2000; Porjesz and Begleiter, 1997), but these abnormalities could be markers of inherited risk for alcoholism, as well (Almasy et al., 1999; O'Connor et al., 1994; Wright et al., 2001). P3a and P3b variations are hypothesized to relate how alcohol and other substance use affects differential neurotransmitter levels within and between individuals (Polich and Criado, 2006).

High-risk drinking patterns and alcohol abuse are associated with other types of substance use and abuse, especially tobacco use and nicotine dependence. Alcohol dependence and regular tobacco use share genetic covariance, even when sociodemographic and personality variables, as well as histories of other psychopathologies are taken into account (Bierut et al., 2000; Li et al., 2007; Madden et al., 2000). Furthermore, the joint trajectories of smoking and drinking across adolescence appear to be more heritable than either one alone (Jackson et al., 2009). Accordingly, P3 measures of alcoholism risk in young adults may be modulated by concurrent smoking status. Studies of young adults suggest that the reduction of visual P3 amplitude in those at elevated risk for alcoholism is enhanced by current smoking patterns (Anokhin et al., 2000; Polich and Ochoa, 2004). Moreover, in these studies tobacco smoking accounted for a larger proportion of the total variance than did alcoholism risk per se. Alcohol abuse and dependence in adolescence is often associated with behavioral psychopathology: behavioral disorders that commonly co-occur with alcohol use disorders in adolescents include conduct disorders and antisocial personality, and mood and anxiety disorders. Behavioral disorders may both precipitate alcohol use disorders and result from them (Clark and Bukstein, 1998).

Here, we addressed the longitudinal effects of adolescent alcohol abuse on brain function in co-twins highly concordant and discordant for their self-reported alcohol problems in late adolescence. Alcohol use was assessed on 4 occasions between ages 16 and 25. We hypothesized that even when genetic and common environmental factors are controlled, a correlation between alcohol abuse and P3 measures will remain, and we tested that hypothesis in both between-family and within-family associations.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Twin pairs were recruited from FinnTwin16-25 (FT16-25), a longitudinal study of 5 consecutive birth cohorts of Finnish twins. FT16-25 was initiated during 1991 when twins from the first cohort, born in 1975, were sequentially enrolled over 12 months time as twins reached age 16. After 60 months of baseline data-collection from all 5 cohorts was completed, pair-wise response rates exceeded 88%, yielding baseline data on 2,733 twin pairs. Subsequent follow-up assessments were made at age 17, 18½, and 25. From all participating twins in these questionnaire studies, 448 twin pairs were selected for laboratory studies conducted in Helsinki. One or both co-twins were never reached in 16 of the invited pairs; an additional 32 pairs were ineligible for participation, because 1 or both co-twins were living outside Finland (N = 13); because 1 or both co-twins was ill, in late stages of pregnancy, or handicapped (N = 18); or deceased (N = 1). Of the 436 eligible pairs successfully contacted and invited to participate, 300 (68.8%) did so. The first 177 of these normally hearing twin pairs (plus individual twins from 4 twin pairs in which only 1 co-twin contributed ERP data) completed a full-day study protocol including EEG/ERP assessments; these 177 twin pairs (46 monozygotic [MZ], 131 dizygotic [DZ], including 49 brother-sister twin pairs) and individual twins from 4 other twin pairs contributed data for the results we here report. These 358 individual twins (187 females, 171 males) ranged in age from 23 to 28 (mean age = 25.8, SD = 1.0) at the time of ERP assessments. Travel and overnight accommodation were provided for twins coming from a distance, and all participant twins were paid a modest incentive. All study protocols were approved by the IRB at Indiana University and by the Ethics Committee of the Helsinki metropolitan hospital district.

Twin pairs for laboratory study were selected on the basis of their extreme discordance and concordance (EDAC) for self-reported scores on the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; White and Labouvie, 1989) at age 18½. For a description of the realized samples for laboratory studies, including protocols not assessing ERPs and randomly selected as well as EDAC selected twins, see Latvala and colleagues (2011), where Supplementary Table 2, available online, provides summary RAPI scores for twins from discordant, concordant, and randomly selected pairs, by their zygosity. EDAC-selected twins were invited for a laboratory protocol that included a structured psychiatric interview, anthropometric measures, group and individual neuropsychological testing, a blood or saliva sample, and for the first 181 twin pairs, EEG/ERP measures. Zygosity determination of all same-sex twin pairs in the laboratory subsamples was made from multiple genetic markers assayed at laboratories of the National Public Health Institute in Helsinki.

Procedure

Alcohol use patterns were assessed with questionnaires containing common item content administered at ages 16, 17, 18½, and 23 to 25 years and, for laboratory-studied twins, by an interview at age 25 (Semi-Structured Assessment for Genetics of Alcoholism [SSAGA]), yielding Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised [DSM-III-R] diagnosis of alcohol dependence. Questionnaires included extensive assessments of health habits and lifestyle, including a 22-item RAPI (White and Labouvie, 1989) at ages 18½ and 23 to 25, and an 11-item Malmö-Modified Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (Mm-MAST) (Dick et al., 2011; Seppä et al., 1990), as well as a lifetime measure of maximum number of drinks consumed in a 24-hour period (MAX-D24) at age 23 to 25. Adolescent RAPI scores are predictive of alcohol dependency diagnoses in early adulthood, correlating ∼0.5 with symptom counts and with a ∼75% probability that late adolescent RAPI scores will be higher among those with a diagnosis at age 25 follow-up than among those without (Dick et al., 2011). Lifetime self-report of MAX-D24 is predictive of diagnosis, as well, and both measures offer quantitative measures to grade drinking habits of nonalcoholic individuals (Saccone et al., 2000). The heritability of the logarithm transformation of MAX-D24, analogous to the transformation used in this study, approximates 50% (A. Heath, unpublished data). These variables were recoded as continuous measures, and a logarithm transformation was conducted so that they would better meet the assumptions of normality. Smoking habits were classified into 2 classes, smoking currently and not smoking currently, from the questionnaire administered at ages 23 to 25. We categorized “smoking currently” as smoking at least once a week and “not smoking currently” as smoking less often or not at all. Distributions of demographic characteristics, alcohol use measures and covariates for the studied twins, by zygosity, are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distributions, Means, and Standard Deviations (SD) of Extremely Discordant and Concordant (EDAC) and Randomly Selected Twin Samples, Alcohol Variables and Covariates in Monozygotic (MZ) and Dizygotic (DZ) Twin Individuals

| MZ (N = 94) |

DZ (N = 264) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 25.9 (1.1) | 25.7 (1.0) |

| Female, n (%) | 57 (60.6) | 130 (49.2) |

| Male, n (%) | 37 (39.4) | 134 (50.8) |

| EDAC sample: Concordant alcohol use, n (%) | 37 (39.4) | 74 (28.0) |

| EDAC sample: discordant alcohol use, n (%) | 41 (43.6) | 151 (57.2) |

| Non-EDAC sample, n (%) | 16 (17.0) | 39 (14.8) |

| RAPI18, mean (SD) | 36.2 (9.4) | 34.2 (9.3) |

| RAPI25, mean (SD) | 33.0 (10.0) | 30.9 (8.7) |

| Mm-MAST, mean (SD) | 5.8 (2.8) | 5.1 (3.0) |

| MAX-D24, mean (SD) | 19.3 (8.2) | 20.0 (9.9) |

| Alcohol abuse or dependence, n (%) | 55 (58.5) | 130 (49.2) |

| Alcohol dependence symptoms, mean (SD) | 2.9 (1.9) | 2.7 (2.1) |

| Current smokers: smoking at least once a week, n (%) | 46 (48.9) | 111 (42.1) |

| Drug abuse or dependence, n (%) | 0 | 3 (1.1) |

| Antisocial personality disorder, n (%) | 7 (7.5) | 14 (5.3) |

| Depressive disorder, n (%) | 27 (28.7) | 80 (30.3) |

| Anxiety disorder, n (%) | 13 (13.8) | 17 (6.4) |

| Educational level: high school graduates, n (%) | 62 (66.0) | 152 (57.6) |

| Married or cohabiting with spouse, n (%) | 42 (44.7) | 130 (49.2) |

Alcohol variables include Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index at age 18 (RAPI18), Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index at age 25 (RAPI25), Malmö-Modified Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (Mm-MAST) at age 25, and “Maximum number of drinks consumed in a 24-hour period” (MAX-D24) at age 25. N = 358 individual twins.

Stimuli and Tasks

Our ERP paradigms were modified from Knight (1984, 1996) and Knight et al. (1989). Subjects were binaurally presented with a quasi-random sequence of 1,000-Hz standard (p = 0.68) and 1,500-Hz target tones (p = 0.16), and physically complex unique novel sounds (p = 0.16), 60 dB over the subjective hearing threshold at a 1.2-second interstimulus interval (NeuroStim; Neurosoft Inc., Charlotte, NC). The duration of standard and target tones was 40 milliseconds (10 milliseconds rise/fall time) and that of the novel sounds 75 to 358 milliseconds. The sequence included 600 sounds and was divided into 3 blocks of 200 sounds each. Subjects were instructed to press a button upon hearing a target, but not to respond to standards or novel sounds. The mean duration of recordings including instructions was 20 minutes. The main experiment was preceded by a training session, consisting of 50 target tones, for which subjects were instructed to press a button every time upon hearing a target.

EEG Recordings and Analysis

Nose-referenced EEG was recorded (low pass 100 Hz, sampling rate 500 Hz) using a 64-channel electrode cap (Virtanen et al., 1996) in an electrically shielded room. Stimulus-locked 900-millisecond EEG epochs (100-millisecond prestimulus baseline) were filtered off-line at 0.01 to 24 Hz, and averaged off-line separately for the standards, targets, and novel sounds. Horizontal and vertical eye movements were monitored with electro-oculogram (EOG) electrodes placed below and lateral to the left eye. Epochs containing deflections >150 μV at any of the EOG or EEG channels were rejected.

The novel-sound N2 and P3 were quantified from novel-minus-standard difference ERPs. The target N2 and P3 were quantified from the subtraction between the target ERPs and training-session ERPs including only targets, to control for activities related to motor preparation. Amplitude averages of the F-line (F1, Fz, and F2), C-line (C1, Cz, and C2), and P-line (P1, Pz, P2) electrodes were calculated at the peak latency determined from the electrode location where each component was expected to be maximal. In addition to reducing the number of statistical comparisons, this procedure was expected to reduce the account of uncorrelated noise across the individual electrodes within a set and, subsequently, to improve the signal/noise ratio (SNR) of our ERP measures. The novel-sound N2 latency was determined from the most negative peak at FCz (an electrode between Fz- and Cz-lines) at 150 to 350 milliseconds poststimulus, the novel-sound P3 latency from the most positive peak at Cz at 200 to 550 milliseconds, the target N2 latency from the most negative peak at Cz at 150 to 350 milliseconds, and the target P3 latency from the most positive peak at CPz (an electrode between Cz- and Pz-lines) at 200 to 550 milliseconds. The latencies of standard-tone N1 (50 to 150 milliseconds poststimulus) and P2 (150 to 300 milliseconds poststimulus onset) components were determined at the FCz. Mean latencies and amplitudes of novel P3, target P3 and standard P2 are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Grand Mean Latencies and Amplitudes of Novel P3, Target P3, and Standard P2 (SD in Parentheses)

| Latency (milliseconds) | Frontal amp. (μV) | Central amp. (μV) | Parietal amp. (μV) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Novel P3 | 297 (37.2) | 12.6 (7.0) | 17.4 (8.0) | 14.9 (7.2) |

| Target P3 | 403 (78.2) | 5.6 (7.5) | 9.7 (8.0) | 16.1 (8.1) |

| Standard P2 | 225 (33.6) | 3.4 (3.2) | 6.9 (3.5) | 5.7 (3.1) |

N for Novel P3 = 294 twins; Target P3, 216; Standard P2, 304.

Statistical Analysis

Hierarchical Multiple Regression

Alcohol effects on brain function were analyzed using a hierarchical multiple regression (HMR) analysis of the amplitude and latency values of ERPs and self-reported alcohol use measures. An HMR approach was used to model the influence of a co-twin's measured effects on the ERP variables being studied in each twin, taking into account other covariates of the twin and variables common to both co-twins of each pair, including their zygosity. The HMR analysis permits testing for main effects and interactions among genetic factors, alcohol use, and ERP change: Heitmann and colleagues (1997), Kaprio and colleagues (1987), and Rose and colleagues (1988) illustrate HMR analyses of other measures.

These HMR models were constructed to predict ERP value in 1 twin (twin A) from the ERP value of the co-twin (twin B), that pair's zygosity; the alcohol use for twin A, and the two-way cross-product terms of zygosity and twin B ERP value, zygosity and twin A alcohol use, and twin B ERP value and twin A alcohol use; finally, the three-way interaction term of zygosity, alcohol use, and twin B ERP value was obtained. The analyses yielded significance tests for genetic effects and evaluated the modulation of such genetic effects by the ERP value of the co-twin and alcohol use. Furthermore, all models included the main effects of smoking status and gender. Table 3 specifies the hierarchical models and interprets their meaning when significant. Note that the main effects of zygosity, gender, smoking and alcohol use, and interactions among them can affect only the ERP values of individual twins, rather than the pair-wise similarity in ERP values of twin pairs. Determining such effects are not, accordingly, our primary goal. Instead, we target interactions that influence intrapair resemblance, and, of these, we particularly focus on the two-way interactions that test whether intrapair similarities in the twins' ERP values change with their alcohol use. These interactions are the central focus of our analyses. Three-way interactions test whether genetic influences (indexed by MZ vs. DZ comparisons) modulate pairwise differences associated with alcohol use; these are of obvious interest, as well. But because we selected twin pairs based on their intrapair similarities and differences for adolescent alcohol-related problems, and because larger differences are less often observed among MZ twin pairs, the three-way interactions in these results must be interpreted with caution and regarded as suggestive only, pending confirmation in a fully representative twin sample.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analysis for the Amplitude and Latency Values of Event-Related Potentials (ERPs) and Self-Reported Alcohol Use Measures

| Terms affecting | Interpretation of term when it is significant |

|---|---|

| Individual ERP values | |

| Zygosity | ERP values differ in MZ and DZ twins |

| Gender | ERP values differ in twins of different gender |

| Smoking | ERP values differ in twins of different smoking habits |

| Alcohol use | ERP values differ in twins of different alcohol use |

| Zygosity × alcohol use | Alcohol use effects on ERP values differ in MZ and DZ twins |

| Intrapair differences in ERP values | |

| Co-twin's ERP value | Similarity in twins' ERP values independent of twin type |

| Zygosity × co-twin's ERP value | Similarity in twins' ERP values depends on their zygosity |

| Co-twin's ERP value × alcohol use | Similarity in twins' ERP values depends on their alcohol use |

| Zygosity × co-twin's ERP value × alcohol use | Effect of alcohol use on twins' similarity depends on zygosity |

DZ, dizygotic; MZ, monozygotic.

Correlational Analyses

In other analyses, we tested for an association of ERP variables with alcohol measures via their correlations. First, in between-family analysis of twins as individuals, we correlated individual alcohol measures with ERP variables for all twins in which both co-twins had usable data, the same samples used for HMR analysis. Then, in 2 within-family analyses, we exploited the paired co-twin structure of our data. These within-family analyses control for unmeasured—and often unknown—between family confounds (e.g., known confounds include parental drinking history, family structure and status, household environment) that could mediate associations of brain function and drinking history among adolescents. In the first approach, we compared ERP measures in co-twins from twin pairs discordant for DSM-III-R diagnosis of alcohol disorder; discordant co-twins, especially discordant MZ co-twins, offer an incisive analytic tool (Dick et al., 2000), although, often, when both predictor (here, drinking measures) and outcome (here, ERP measures) are moderately heritable, discordant co-twins will be limited in number, and power will be constrained. In a second within-family analysis, we used all twin pairs with usable data from both co-twins on both sets of measures and correlated intrapair differences in drinking measures with intrapair differences in ERP variables; the quasi-continuous nature of both drinking and ERP measures was expected to give this analysis necessary power for within-family confirmation of effects of drinking on ERP amplitude and latency.

Results

Sample Selection

Selection of twins for the ERP laboratory study was based on their intrapair differences in RAPI scores (22 items with 4 response alternatives to yield a 66-point potential range) at age 18½. Extremely RAPI-discordant twin pairs were of major interest for their informational yield in planned candidate gene studies and for evaluating possible effects of differential exposure to alcohol during adolescence in within-family comparisons. RAPI scores at age 18½ significantly correlated (0.39) in the full sample of > 2,500 twin pairs, and to no surprise, more highly for MZ than same-sex DZ twin pairs. Accordingly, RAPI-discordant co-twins are disproportionately DZ twin pairs; RAPI-discordant MZ twin pairs are more often twin sisters than twin brothers, and in extremely RAPI-discordant brother–sister twin pairs, it is the brother, more often than the sister, who has the high RAPI score in late adolescence.

DZ twins comprise nearly three-fourths of the realized sample for ERP study, rather than the two-thirds of the full population sample from which the sample was selected. Means and variances of adolescent RAPI scores of the 358 ERP-studied twins, and, more important, their mean absolute intrapair RAPI differences and the variances of those differences are substantially elevated from the full sample of twins assessed at that age. The mean absolute difference in RAPI scores at age 18½ for twin pairs selected for laboratory study approached 1.7 times that of the full sample of twins (N = 5,080) from which it was drawn, and the variance of those absolute differences among selected twin pairs was elevated 1.4 times above that of the full sample. Twins selected for RAPI-discordance (with an intrapair difference ≥10 points on the 66-point possible range of RAPI scores) approximate the upper one-sixth of the distribution of intrapair RAPI differences across all ∼2,500 twin pairs in the epidemiological sample from which they were drawn. Similar, but substantially smaller, effects were found for individual RAPI and Mm-MAST scores and their intrapair differences at age 25. EDAC selection was clearly effective, for it yielded a selected sample of twins with markedly elevated rates of diagnosed alcohol dependency or abuse (51.6% of the 358 individual twins selected for ERP study), a sample unusually informative for within-family study of effects of adolescent alcohol exposure, albeit a selected sample not fully representative of the base population from which it was drawn. For all analyses, we used all twins from twin pairs in which both co-twins had usable ERP data, necessarily deleting pairs in which 1 or both co-twins had unusable ERP results. After pairwise deletion, the analyzed samples were the same for both correlational and HMR analyses with realized samples of 152 twin pairs for P2, 147 pairs for novel P3, and for target P3, for which SNR is smaller, a sample of 108 twin pairs; 90% of the pairs with usable ERP data were pairs for whom we had all of the drinking outcome data from both co-twins.

Behavioral Task Performance

In the main experiment, the average reaction time to targets was 451 milliseconds (SD = 75) and hit rate was 96.1% (SD = 5.3). In the training session, the average reaction time was 286 milliseconds (SD = 114) and hit rate 99.6% (SD = 3.4). We calculated correlations across reaction times and hit rates with alcohol use variables. Commonly, there were no statistically significant correlations, but we found some single ones; in the main experiment, reaction time correlated negatively with alcohol use, as measured with MAX-D24 (r = −0.15, p < 0.05) and hit rate correlated positively with alcohol use, as measured with RAPI at age 18 (r = 0.17, p < 0.05). In the training session, hit rate correlated positively with alcohol use, measured with MAX-D24 (r = 0.16, p < 0.05).

Between-Family Association of ERPs with Alcohol Use

Phenotypic correlations of novel and target P3 and standard P2 with 4 measures of alcohol use using twins as individuals are presented in Table 4. All 3 novel-sound P3 (novel P3) amplitude values correlated negatively and the P2 latency positively (with p < 0.001) with lifetime report of “Maximum number of drinks consumed in a 24-hour period,” MAX-D24. Target P3 latencies correlated negatively (p < 0.05) with each of the 3 other self-reports of alcohol use including RAPI from the questionnaire at age 18½.

Table 4.

Phenotypic Correlations (Pearson) of P3 and P2 for Twins as Individuals (N for Novel P3 = 294; Target P3, 216; Standard P2, 304) with Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index at Age 18 (RAPI18), Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index at Age 25 (RAPI25), “Maximum Number of Drinks Consumed in a 24-Hour Period” (MAX-D24), and Malmö-Modified Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (Mm-MAST) at Age 25

| RAPI18 | RAPI25 | MAX-D24 | Mm-MAST | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Novel P3 | ||||

| Latency | ||||

| Frontal amp. | −0.20*** | |||

| Central amp. | −0.21*** | |||

| Parietal amp. | −0.18** | |||

| Target P3 | ||||

| Latency | −0.15* | −0.15* | −0.12§ | |

| Frontal amp. | ||||

| Central amp. | ||||

| Parietal amp. | ||||

| Standard P2 | ||||

| Latency | 0.22*** | |||

| Frontal amp. | ||||

| Central amp. | ||||

| Parietal amp. | −0.10§ |

Only statistically significant, and trend-level, results are shown.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001,

p < 0.10.

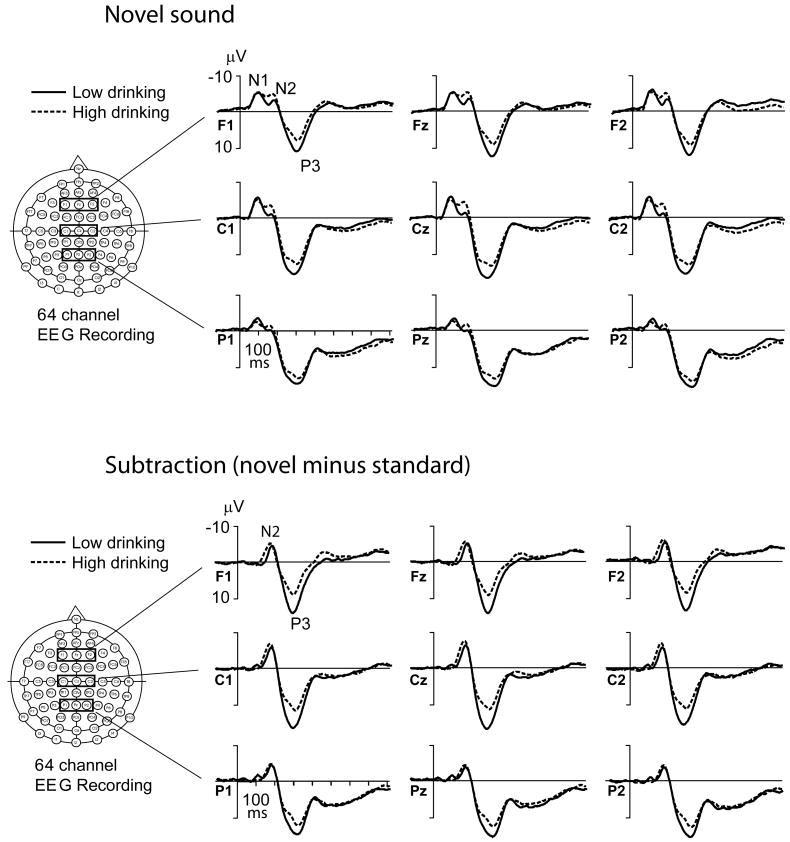

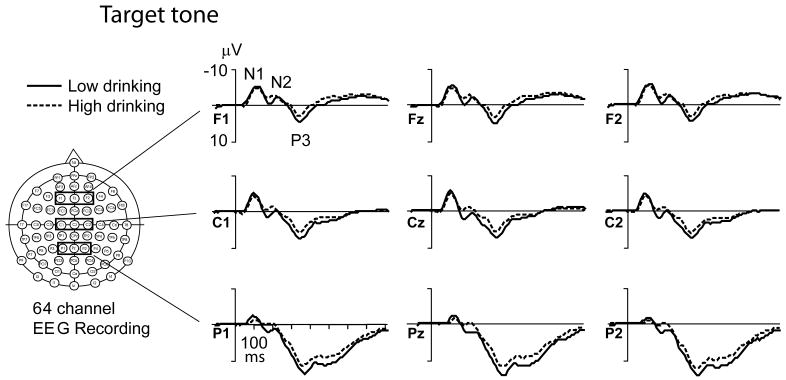

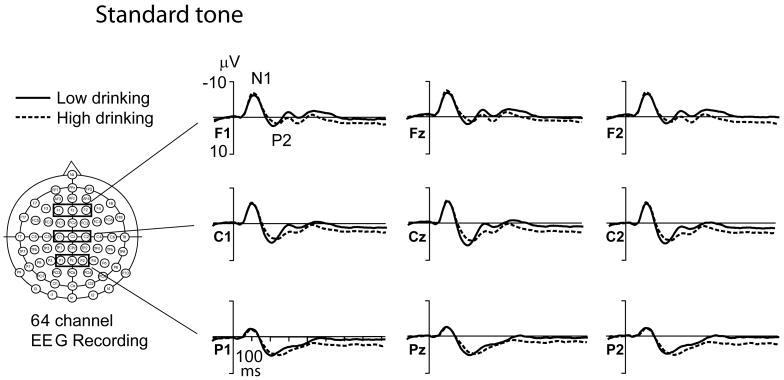

Novel P3 amplitude correlated negatively, and novel P3 latency correlated positively, with alcohol use, especially as indexed by high-density drinking. Figure 1 compares grand-average ERPs to novel sounds and grand-average difference ERPs to novel versus standard tones in 2 subgroups (N = 36 individual twins in each) representing the extremes (highest and lowest deciles) of self-reported high-density drinking, MAX-D24. Figure 2 shows the grand-average ERPs to target tones, and Fig. 3 the grand-average ERPs to standard tones in these same 2 groups on N = 36 each.

Fig. 1.

Grand-average event-related potential (ERP) waves (novel) and difference waves (novel minus standard) in “Low-drinking” and “High-drinking” twins, indicating a decrease of P3 amplitude for the novel sounds associated with alcohol use, as measured with the variable “Maximum number of drinks consumed in a 24-hour period” (MAX-D24) at age 25. “Low-drinking” twins are those in the lowest decile (N = 36) of maximum drinks consumed in a 24-hour period (MAX-D24 mean = 6.7, SD = 2.4) and “High-drinking” twins are those in the highest drinking decile (N = 36, MAX-D24 mean = 36.7, SD = 3.4) drawn from the total ERP twin sample.

Fig. 2.

Grand-average event-related potential (ERP) waves in “Low-drinking” and “High-drinking” twins for the target tones. Alcohol use is measured with the variable “Maximum number of drinks consumed in a 24-hour period” (MAX-D24) at age 25. Same 2 groupings, N = 36 each, as in Fig. 1. EEG, electroencephalogram.

Fig. 3.

Grand-average event-related potential (ERP) waves in “Low-drinking” and “High-drinking” twins for the standard tones. Alcohol use is measured with the variable “Maximum number of drinks consumed in a 24-hour period” (MAX-D24) at age 25. Same 2 groupings, N = 36 each, as in Fig. 1. EEG, electroencephalogram.

Within-Family Association of ERPs with Alcohol Use

We conducted within-family analyses among twin pairs discordant for alcohol diagnosis (DSM-III-R) at age 25, testing for P3 and P2 differences with paired-samples t-tests. Given substantial heritability for symptom counts and high concordance for diagnosis in this selected sample of twins, of whom half satisfied diagnostic criteria, our sample of discordant pairs was small (N = 20), and these analyses yielded no statistically significant results. Pairs were defined discordant when 1 co-twin met criteria for DSM-III-R diagnosis of alcohol dependence and the co-twin was symptom-free, that is, fulfilled none of the alcohol dependence criteria on SSAGA interview at age 25.

However, using all pairs with usable ERP data and quasi-continuous outcome measures for greater statistical power, we correlated within-pair difference scores of ERP variables with within-pair differences in alcohol use/abuse (self-reported alcohol use measures and alcohol dependence criteria symptom counts). Results show that the 3 novel P3 amplitude values correlated negatively, and statistically significantly, with 1 measure of alcohol use. The difference scores of novel P3 frontal (r = −0.28, p < 0.01), central (r = −0.23, p < 0.01), and parietal (r = −0.20, p < 0.05) amplitudes correlated negatively with difference scores of high-density alcohol use, measured by MAX-D24. High-density drinking was associated with low amplitude novel P3. Within-pair differences in this lifetime measure of high-density drinking were as closely associated with within-pair differences in novel P3 amplitudes as were the correlations of MAX-D24 across twins as individuals (see column 3 of Table 4): intrapair difference correlations matched the magnitude of interindividual correlations of these variables. The association was not reduced by controlling for between family confounds. The other 3 self-report measures of alcohol use we used, including self-reported alcohol problems at age 18½ and 25, showed not such robust associations with any P3 variable.

MAX-D24 was not associated with target P3 either. Notably, this was not a consequence of twin pair selection, although the realized sample for target P3 was smaller than that for novel P3. Within-pair correlations across the 108 twin pairs common to both novel and target P3 yielded parallel results, with a significant and slightly higher correlation of MAX-D24 with novel P3, and with no change in its negligible correlation with target P3.

HMR Analyses of P3

A significant genetic influence on target P3 generation was found, but no significant associations of target P3 with alcohol use were observed. In contrast, variation in novel P3 latency was attributed to gene–environment interactions. P3 latency correlated positively with the Mm-MAST, and the effects of the Mm-MAST on P3 latency were significantly modified by genetic influences (Table 5). Similarly, the variation in parietal amplitude of novel P3 was attributable to gene–environment interaction. The effect of alcohol abuse, as measured with RAPI at age 18, on parietal amplitude of novel P3 was modified significantly by genetic influences. At the same time, P3 amplitude correlated negatively with RAPI (Table 6).

Table 5.

Regression Coefficients (β) and Standard Errors (SE) of the Novel P3 of Twin A from the Main Effects as well as Two- and Three-Way Interactions of the Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analyses with Malmö-Modified Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (Mm-MAST) at Age 25

| Latency | Frontal amp. | Central amp. | Parietal amp. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| P3twin B | 0.26*** | 0.06 | 0.35*** | 0.06 | 0.38*** | 0.07 | ||

| Zygosity | ||||||||

| Gender | 2.14* | 0.99 | 2.88** | 1.15 | 1.88§ | 1.12 | ||

| Smoking | −3.54*** | 0.98 | −4.42*** | 1.13 | −4.40*** | 1.10 | ||

| Mm-MAST | 5.67 | 4.59 | 8.77§ | 5.29 | 10.58* | 5.19 | ||

| Zygosity × Mm-MAST | −99.43§ | 57.47 | ||||||

| Zygosity × P3twin B | 0.35§ | 0.19 | 0.35* | 0.15 | ||||

| P3twin B × Mm-MAST | ||||||||

| Zygosity × P3twin B × Mm-MAST | 3.62** | 1.46 | ||||||

Only statistically significant, and trend-level, results are shown. N = 147 twin pairs.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001,

p < 0.10.

Table 6.

Regression Coefficients (β) and Standard Errors (SE) of the Novel P3 of Twin A from the Main Effects as well as Two- and Three-Way Interactions of the Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analyses with Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI) at Ages 18 and 25

| Latency | Frontal amp. | Central amp. | Parietal amp. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| P3twin B | 18 | 0.11§ | 0.06 | 0.27*** | 0.06 | 0.35*** | 0.06 | 0.37*** | 0.07 |

| 25 | 0.27*** | 0.06 | 0.36*** | 0.06 | 0.37*** | 0.08 | |||

| Zygosity | 18 | ||||||||

| 25 | |||||||||

| Gender | 18 | 2.35* | 0.96 | 2.88** | 1.09 | ||||

| 25 | 2.05* | 0.97 | 2.67* | 1.13 | |||||

| Smoking | 18 | −3.41*** | 0.97 | −4.23*** | 1.09 | −4.38*** | 1.07 | ||

| 25 | −3.47*** | 0.96 | −4.22*** | 1.11 | −4.06*** | 1.10 | |||

| RAPI | 18 | ||||||||

| 25 | 5.31§ | 3.12 | |||||||

| Zygosity × RAPI | 18 | ||||||||

| 25 | |||||||||

| Zygosity × P3twin B | 18 | 0.39* | 0.18 | 0.24§ | 0.14 | 0.35* | 0.15 | ||

| 25 | 0.37* | 0.18 | 0.26§ | 0.14 | 0.39* | 0.15 | |||

| P3twin B × RAPI | 18 | ||||||||

| 25 | −0.87* | 0.40 | |||||||

| Zygosity × P3twin B × RAPI | 18 | −2.64** | 0.97 | ||||||

| 25 | |||||||||

Only statistically significant, and trend-level, results are shown. N = 147 twin pairs.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001,

p < 0.10.

Individual variation in the frontal amplitude of novel P3 was influenced by effects of alcohol and by gene–environment interactions. In these models, alcohol abuse, as measured with RAPI at age 25, was significantly associated with variation of novel P3 amplitude. Specifically, the amplitude of novel P3 correlated negatively with RAPI, and P3 amplitude correlated negatively with alcohol use (Table 6). HMR results show that alcohol use, as measured with MAX-D24, a lifetime report of “Maximum number of drinks consumed in a 24-hour period,” was marginally significantly associated with variation in P3 amplitude (Table 7).

Table 7.

Regression Coefficients (β) and Standard Errors (SE) of the Novel P3 of Twin A from the Main Effects as well as Two- and Three-Way Interactions of the Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analyses with “Maximum Number of Drinks Consumed in a 24-hour Period” (MAX-D24) at Age 25, With and Without Smoking as Covariate

| Latency | Frontal amp. | Central amp. | Parietal amp. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| With smoking | ||||||||

| P3twin B | 0.27*** | 0.06 | 0.36*** | 0.07 | 0.37*** | 0.08 | ||

| Zygosity | ||||||||

| Gender | 2.84* | 1.44 | ||||||

| Smoking | −3.45*** | 0.99 | −4.18*** | 1.15 | −3.91*** | 1.14 | ||

| MAX-D24 | ||||||||

| Zygosity × MAX-D24 | ||||||||

| Zygosity × P3twin B | 0.34§ | 0.19 | 0.36* | 0.16 | ||||

| P3twin B × MAX-D24 | −0.32§ | 0.17 | ||||||

| Zygosity × P3twin B × MAX-D24 | ||||||||

| Without smoking | ||||||||

| P3twin B | 0.27*** | 0.07 | 0.36*** | 0.07 | 0.38*** | 0.08 | ||

| Zygosity | ||||||||

| Gender | 3.08* | 1.50 | ||||||

| MAX-D24 | ||||||||

| Zygosity × MAX-D24 | ||||||||

| Zygosity × P3twin B | −0.34§ | 0.19 | −0.43** | 0.17 | ||||

| P3twin B × MAX-D24 | −0.43* | 0.17 | −0.32§ | 0.19 | ||||

| Zygosity × P3twin B × MAX-D24 | ||||||||

Only statistically significant, and trend-level, results are shown. N = 147 pairs.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001,

p < 0.10.

We then carried out corresponding analyses for the P3 values and our several alcohol use measures without including tobacco variable. These supplemental analyses excluding the tobacco variable were highly consistent with the main analyses in which they were included (Table 7).

Frontal P2 amplitude also reflected effects of gene– environment interactions. The effect of alcohol abuse, as measured with RAPI at age 18, was modified significantly by genetic influences on the P2 amplitude (β = −3.46, p < 0.05, SE = 1.44). At the same time, P2 amplitude correlated negatively with RAPI. Similar effects were found for variation in P2 frontal amplitude: the measure of high-density drinking MAX-D24 was significantly associated with variation in P2 amplitude and the association between alcohol use and variation in frontal P2 amplitude was modified significantly by genetic influences on frontal P2 amplitude (β = −0.39, p < 0.05, SE = 0.18).

Discussion

Our analyses address a long-standing question: Does adolescent alcohol abuse have demonstrable effects on neurophysiological function in early adulthood? Our results, most consistently found in an association of a lifetime report of high-density drinking with novel P3, offer some positive answers. Maximum number of drinks consumed in a 24-hour period, MAX-24D, significantly correlated (negatively), across all 358 twins, with the amplitude of novel P3 from all 3 measured electrode sites. Importantly, and convincingly, the between-family association of MAX-24D with novel P3 amplitude was fully confirmed in within-family analysis of twin pairs, an analysis that correlated intrapair differences in MAX-24D with intrapair differences in novel P3 amplitudes for all 177 twin pairs. The magnitude of these correlations was modest, but we emphasize that the pairwise correlations of intrapair differences (ranging from −0.20 to −0.28 across the 3 P3 sites) were fully consistent with the parallel correlations based on the twins as individuals (−0.18 to −0.21). Correlations of intrapair differences in alcohol use with intrapair differences in P3 offer some within-family control for many unmeasured between-family confounds, including family history and parental alcohol use, confounds that could mediate any association between drinking patterns of young adults and their neurophysiological functions. Accordingly, the consistency in our 2 sets of correlational results offers evidence of an association between binge drinking and novel P3 amplitude, with additional evidence that the association is unlikely because of unmeasured third variable family confounds.

In complementary analyses, we addressed the effect of alcohol use on P3 by incorporating ERP measures and longitudinal self-reports of alcohol use from these Finnish twins into HMR analyses. The HMR analyses offer additional evidence that co-twin similarity for novel P3 is modulated by the twins' alcohol use and abuse. Some of the HMR results suggest three-way interactions in which these associations are modified by genetic similarity. But because our laboratory sample of twins was selected, pairwise, for the co-twins' concordance/discordance for adolescent alcohol problems, inferences of genetic effects from this sample must be made with caution.

Why did we find evidence of adolescent alcohol effects on P3 that have eluded others? We found that both alcohol use and genetic factors play significant roles in P3 generation but only for novel P3. For target P3, the focus of many earlier studies, a significant genetic influence on generation was observed, but in the absence of significant associations or interactions with alcohol use. Might novel P3 be specifically sensitive to alcohol effects? Amplitude of P3 to novel sounds correlated negatively with self-reported alcohol use, as measured with RAPI and MAX-D24. P3 elicited by novel sounds may correspond to a “novelty P3,” sharing resemblance with the P3a subcomponent, elicited specifically by perceptually novel “distracter” stimuli in easy discrimination conditions (such as ours). This “novelty P3,” analogous to the P3 to novel stimuli in our data has a frontal/central maximum amplitude distribution, and it is thought to be associated with redirection of attention monitoring (Polich, 2007; Polich and Criado, 2006). Consistent with previous studies in chronic alcoholics (Hada et al., 2000;Rodriguez Holguin et al., 1999a), subjects with more severe drinking histories than our twin subjects, our results thus suggest that long-term neuronal effects of alcohol abuse are reflected by reduced amplitude of P3 to novel sounds. This result may seem to contradict a previous interpretation that novel P3 amplitude is a genetic marker of vulnerability to, rather than consequence of, alcohol abuse (Hada et al., 2001; Porjesz and Begleiter, 1997; Rodriguez Holguin et al., 1999b). It is, therefore, important to note that the clearest associations with genetic predisposition to alcoholism have been found in the visual modality, specifically associated with target P3s, instead of novelty detection (Polich et al., 1994). Our analyses also suggest, albeit tentatively, that genetic factors influence the association between adolescent alcohol abuse and diminished P3 to novel sounds. Stated differently, the detrimental neuronal effects reflected by the novel P3 diminution might be most severe in individuals with an inherited dispositional sensitivity to ethanol. At the same time, there are essential methodological differences between the above-mentioned studies (Hada et al., 2001; Porjesz and Begleiter, 1997; Rodriguez Holguin et al., 1999b) and ours. Our subjects were selected for ERP study on the basis of their individual drinking histories, not the drinking histories of (1 or both of) their parents. Furthermore, we studied twin pairs selected for their concordance/discordance in drinking-related problems in late adolescence. A longitudinal twin-family design (twin pairs concordant or discordant for their own alcohol use with pairs varying in familial risks for alcohol abuse) may provide a better separation of familial risk from risks resulting from individual drinking history than a typical high-risk familial design.

Our HMR analysis also showed a significant positive correlation between novel P3 latency and self-reported alcohol use. Specifically, delayed novel P3 latency was associated with drinking patterns and problems measured with Mm-MAST. This result, consistent with previous studies suggesting delayed P3 to novel sounds in chronic alcoholics (Biggins et al., 1995), is consistent with the hypothesis that novel P3 latency mainly reflects the effects of ethanol, instead of inherited predisposition. Here, also, our analyses tentatively suggest that genetic factors influence the association between excessive adolescent alcohol use and delayed P3 to novel sounds.

Our paradigm was modified from earlier auditory P3 studies (Knight, 1984, 1996; Knight et al., 1989) on patients with cortex lesions. Interestingly, prefrontal lesions seemed to cause a pattern of P3 changes, a reduced novel-sound P3 at frontal sites and a normal target P3 (Knight, 1984), which resembles our P3 findings associated with adolescent alcohol use. Previous studies suggest that the maturation of prefrontal association areas continues (at least) until the early 20s (e.g., Sowell et al., 1999), and these regions could, thus, be specifically vulnerable to the effects of early-onset ethanol use (Clark et al., 2008; De Bellis et al., 2005; Lubman et al., 2007). Accordingly, we suggest that the correlation between adolescent alcohol use and novel P3 amplitude could be related to prefrontal dysfunctions. Consistent with this interpretation, the negative correlation between novel P3 amplitude and alcohol use was specifically significant in the frontal electrode sites, while the inherited effects were more predominant parietal.

Using a stimulus paradigm similar to ours, Knight (1996) found a pattern analogous to the present results, concentrating on novel P3, in patients suffering from lesions in medial temporal cortex. This area is one of the potential generator sites of novel-sound P3 (Escera et al., 2000), and also a region that suggested to be specifically sensitive to structural effects of early-onset alcohol use (Clark et al., 2008; De Bellis et al., 2000). We speculate that the novel P3 reduction associated with adolescent alcohol use could thus be partially contributed by subtle functional changes in the medial temporal lobe. Given the well-documented role of these areas (as well as frontal areas) in memory and learning, we suggest that these subtle brain changes could interfere with academic performance and lead to experiencing failures that foster increased adolescent alcohol use (Bergen et al., 2005)—a high-risk pathway to later alcohol dependence (Grant et al., 2006).

We also found some significant associations between changes in standard-tone P2 and adolescent alcohol use, as measured with RAPI, and with MAX-D24. Auditory P2 component was proposed by Crowley and Colrain (2004) as mainly reflecting stimulus feature evaluation, and P2 amplitude appears to be under partial genetic control (Katsanis et al., 2007). Our results suggest that both alcohol use and genetic factors could independently modulate P2. Alcohol use was associated with P2 changes and that relationship seems to be modified by genetic similarity. P2 amplitude correlated negatively with self-reported alcohol use, consistent with previous studies suggesting P2 reductions after acute ethanol use (Jääskeläinen et al., 1996) and in chronic alcoholics (Romani and Cosi, 1989).

Finally, smoking habits significantly correlated with P3 amplitude. However, supplemental HMRs without inclusion of the tobacco variable show that smoking per se was not a statistically significant confound. The supplemental analyses were highly consistent with the main analysis in which smoking was included.

Our results suggest that alcohol effects on ERPs may be most sensitively found in novel P3 and suggest, as well, that measures of high-density drinking may more sensitively reveal such effects than either drinking-related problems (e.g., RAPI or Mm-MAST) or DSM-III-R diagnoses of alcohol disorder. Both of these suggestive results require replication, as they may reflect the specific nature of our longitudinal study design, our EDAC sample selection that yielded a high prevalence of alcohol dependency, and our assessment of high-density drinking patterns and ERPs at mean age 25. Persistence of alcohol effects to later ages is uncertain.

A potential confound in studies such as ours is the association of comorbid psychopathology with alcohol abuse and dependence in adolescence (Clark and Bukstein, 1998). One way to deal with this problem is to exclude all subjects with symptoms of other problems. However, it has been shown that using tight exclusion criteria can seriously impair the generalizability of results obtained (Humphreys and Weisner, 2000).

In conclusion, our several analyses of ERPs in an informative sample of young adult twins suggest that novel P3 amplitude correlates negatively with alcohol use and abuse, an association that may reflect altered involuntary attention attributable to gene–environment interactions of dispositional vulnerabilities with high-density drinking histories. This could suggest an impaired involuntary attention shifting from interactive genetic–environmental effects. Novel P3 latency, which was attributed to gene–environment interactions, also correlated positively with alcohol use. We conclude by emphasizing again that drinking patterns of our twin subjects were studied from mid-adolescence into young adulthood with their ERP assessments conducted at a mean age of 25 years; and that of the multiple measures of alcohol use we related to P3, high-density drinking yielded the most consistent evidence. Our results suggest that subtle neurophysiological changes in sound processing and in attention and orienting to environmental changes can be induced by alcohol use during adolescence and early adulthood. That suggestive result invites and awaits definitive confirmation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R37AA012502 and R01AA08315), the Academy of Finland (Center of Excellence in Complex Disease Genetics, and grants 1211486, 118555, 100499), Emil Aaltonen Foundation, Finnish Cultural Foundation, Jenny and Antti Wihuri Foundation, Finnish Foundation for Alcohol Studies, Ella and Georg Ehrnrooth Foundation, and Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation. NIH Awards R01MH083744, R01HD040712, R01NS037462, and R01NS048279 supported JA. We thank Pasi Piiparinen for help with data acquisition.

References

- Ahveninen J, Jääskeläinen I, Pekkonen E, Hallberg A, Hietanen M, Näätänen R, Schröger E, Sillanaukee P. Increased distractibility by task-irrelevant sound changes in abstinent alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:1850–1854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almasy L, Porjesz B, Blangero J, Chorlian DB, O'Connor SJ, Kuperman S, Rohrbaugh J, Bauer LO, Reich T, Polich J, Begleiter H. Heritability of event-related brain potentials in families with a history of alcoholism. Am J Med Genet. 1999;88:383–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anokhin AP, Vedeniapin AB, Sirevaag EJ, Bauer LO, O'Connor SJ, Kuperman S, Porjesz B, Reich T, Begleiter H, Polich J. The P300 brain potential is reduced in smokers. Psychopharmacology. 2000;149:409–413. doi: 10.1007/s002130000387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begleiter H, Porjesz B, Bihari B, Kissin B. Event-related brain potentials in boys at risk for alcoholism. Science. 1984;225:1493–1496. doi: 10.1126/science.6474187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begleiter H, Porjesz B, Rawlings R, Eckardt M. Auditory recovery function and P3 in boys at high risk for alcoholism. Alcohol. 1987;4:315–321. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(87)90029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen HA, Martin G, Roeger L, Allison S. Perceived academic performance and alcohol, tobacco and marijuana use: longitudinal relationships in young community adolescents. Addict Behav. 2005;30:1563–1573. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierut LJ, Schuckit MA, Hesselbrock V, Reich T. Co-occurring risk factors for alcohol dependence and habitual smoking: results from the collaborative study on the genetics of alcoholism. Alcohol Res Health. 2000;24:233–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggins CA, MacKay S, Poole N, Fein G. Delayed P3a in abstinent elderly male chronic alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:1032–1042. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb00985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SR, Iacono WG, McGue M. P300 amplitude in adolescent twins discordant and concordant for alcohol use disorders. Biol Psychol. 2002;61:203–227. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(02)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Bukstein OG. Psychopathology in adolescent alcohol abuse and dependence. Alcohol Health Res World. 1998;22:117–147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Thatcher DL, Tapert SF. Alcohol, psychological dysregulation, and adolescent brain development. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:375–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley KE, Colrain IM. A review of the evidence for P2 being an independent component process: age, sleep and modality. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115:732–744. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2003.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bellis MD, Clark DB, Beers SR, Soloff PH, Boring AM, Hall J, Kersh A, Keshavan MS. Hippocampal volume in adolescent-onset alcohol use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:737–744. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bellis MD, Narasimhan A, Thatcher DL, Keshavan MS, Soloff P, Clark DB. Prefrontal cortex, thalamus, and cerebellar volumes in adolescents and young adults with adolescent-onset alcohol use disorders and comorbid mental disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1590–1600. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000179368.87886.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWit DJ, Adlaf EM, Offord DR, Ogborne AC. Age at first alcohol use: a risk factor for the development of alcohol disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:745–750. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Aliev F, Viken R, Kaprio J, Rose RJ. Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI) scores predict alcohol dependence diagnoses seven years later. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01432.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Johnson JK, Viken RJ, Rose RJ. Testing between-family associations in within-family comparisons. Psychol Sci. 2000;11:409–413. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escera C, Alho K, Schröger E, Winkler I. Involuntary attention and distractibility as evaluated with event-related brain potentials. Audiol Neurotol. 2000;5:151–166. doi: 10.1159/000013877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JD, Scherrer JF, Lynskey MT, Lyons MJ, Eisen SA, Tsuang MT, True WR, Bucholz KK. Adolescent alcohol use is a risk factor for adult alcohol and drug dependence: evidence from a twin design. Psychol Med. 2006;36:109–118. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hada M, Porjesz B, Begleiter H, Polich J. Auditory P3a assessment of male alcoholics. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:276–286. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00236-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hada M, Porjesz B, Chorlian DB, Begleiter H, Polich J. Auditory P3a deficits in male subjects at high risk for alcoholism. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:726–738. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitmann BL, Kaprio J, Harris JR, Rissanen A, Korkeila M, Koskenvuo M. Are genetic determinants of weight gain modified by leisure-time physical activity? A prospective study of Finnish twins. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66:672–678. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.3.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SY, De Bellis MD, Keshavan MS, Lowers L, Shen S, Hall J, Pitts T. Right amygdala volume in adolescent and young adult offspring from families at high risk for developing alcoholism. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:894–905. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SY, Shen S, Lowers L, Locke J. Factors predicting the onset of adolescent drinking in families at high risk for developing alcoholism. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:265–275. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00841-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Weisner C. Use of exclusion criteria in selecting research subjects and its effect on the generalizability of alcohol treatment outcome studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:588–594. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jääskeläinen IP, Näätänen R, Sillanaukee P. Effect of acute ethanol on auditory and visual event related potentials: a review and reinterpretation. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40:284–291. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00385-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Rose RJ, Kaprio J. National Cancer Institute. Phenotypes and Endophenotypes: Foundations for Genetic Studies of Nicotine Use and Dependence. Tobacco Control Monograph No 20. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and HumanServices, National Institute of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2009. Trajectories of tobacco use from adolescence to adulthood: are the most informative phenotypes tobacco specific? NIH Publication No. 09-6366, August 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M, Langinvainio H, Romanov K, Sarna S, Rose RJ. Genetic influences on use and abuse of alcohol: a study of 5638 adult Finnish twin brothers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1987;11:349–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1987.tb01324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsanis J, Iacono WG, McGue MK, Carlson SR. P300 event-related potential heritability in monozygotic and dizygotic twins. Psychophysiology. 2007;34:47–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight RT. Decreased response to novel stimuli after prefrontal lesions in man. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1984;59:9–20. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(84)90016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight RT. Contribution of human hippocampal region to novelty detection. Nature. 1996;383:256–259. doi: 10.1038/383256a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight RT, Scabini D, Woods DL, Clayworth CC. Contributions of temporal-parietal junction to the human auditory P3. Brain Res. 1989;502:109–116. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90466-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latvala A, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Dick DM, Vuoksimaa E, Viken RJ, Suvisaari J, Kaprio J, Rose RJ. Genetic origins of the association between verbal ability and alcohol dependence symptoms in young adulthood. Psychol Med. 2011;41:641–51. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li TK, Volkow ND, Baler RD, Egli M. The biological bases of nicotine and alcohol co-addiction. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubman DI, Yücel M, Hall WD. Substance use and the adolescent brain: a toxic combination? J Psychopharmacol. 2007;21:792–794. doi: 10.1177/0269881107078309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden PA, Bucholz KK, Martin NG, Heath AC. Smoking and the genetic contribution to alcohol-dependence risk. Alcohol Res Health. 2000;24:209–214. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Iacono WG, Legrand LN, Elkins I. Origins and consequences of age at first drink, II. Familial risk and heritability. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1166–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor S, Morzorati S, Christian JC, Li TK. Heritable features of the auditory oddball event-related potential: peaks, latencies, morphology and topography. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1994;92:115–125. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(94)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagan J, Rose RJ, Viken RJ, Pulkkinen L, Kaprio J, Dick DM. Genetic and environmental influences on stages of alcohol use across adolescence into young adulthood. Behav Genet. 2006;36:483–497. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9062-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson BW, Williams HL, McLean GA, Smith LT, Schaeffer KW. Alcoholism and family history of alcoholism: effects on visual and auditory event-related potentials. Alcohol. 1987;4:265–274. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(87)90022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman G, Johnson W, Iacono WG. The heritability of P300 amplitude in 18-year-olds is robust to adolescent alcohol use. Psychophysiology. 2009;46:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00850.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum A, Ford J, White P, Mathalon D. Event-related potentials in alcoholic men: P3 amplitude reflects family history but not alcohol consumption. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1991;15:839–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1991.tb00611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polich J. Updating P300: an integrative theory of P3a and P3b. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118:2128–2148. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polich J, Burns T. P300 from identical twins. Neuropsychologia. 1987;25:299–304. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(87)90143-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polich J, Criado J. Neuropsychology and neuropharmacology of P3a and P3b. Int J Psychophysiol. 2006;60:172–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polich J, Herbst K. P300 as a clinical assay: rationale, evaluation and findings. Int J Psychophysiol. 2000;38:3–19. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(00)00127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polich J, Ochoa CJ. Alcoholism risk, tobacco smoking, and P300 event-related potential. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115:1374–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polich J, Pollock VE, Bloom FE. Meta-analysis of P300 amplitude from males at risk for alcoholism. Psychol Bull. 1994;115:55–73. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porjesz B, Begleiter H. Event-related potentials in coa's. Alcohol Health Res World. 1997;21:236–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Holguin S, Porjesz B, Chorlian DB, Polich J, Begleiter H. Visual P3a in male alcoholics and controls. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999a;23:582–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Holguin S, Porjesz B, Chorlian DB, Polich J, Begleiter H. Visual P3a in male subjects at high risk for alcoholism. Biol Psychiatry. 1999b;46:281–291. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00247-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers TD, Deary I. The P300 component of the auditory event-related potential in monozygotic and dizygotic twins. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991;83:412–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1991.tb05566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romani A, Cosi V. Event-related potentials in chronic alcoholics during withdrawal and abstinence. Neurophysiol Clin. 1989;19:373–384. doi: 10.1016/s0987-7053(89)80090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose RJ, Dick DM, Viken RJ, Kaprio J. Gene–environmental interaction in patterns of adolescent drinking: regional residency moderates longitudinal influences on alcohol use. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:637–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose RJ, Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J, Sarna S, Langinvainio H. Shared genes, shared experiences, and similarity of personality: data from 14,288 adult Finnish co-twins. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:161–171. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saccone NL, Kwon JM, Corbett J, Goate A, Rochberg N, Edenberg HJ, Foroud T, Li TK, Begleiter H, Reich T, Rice JP. A genome screen of maximum number of drinks as an alcoholism phenotype. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2000;96:632–637. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20001009)96:5<632::aid-ajmg8>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SanMiguel I, Morgan HM, Klein C, Linden D, Escera C. On the functional significance of novelty-P3: facilitation by unexpected novel sounds. Biol Psychol. 2010;83:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seppä K, Sillanaukee P, Koivula T. The efficiency of a questionnaire in detecting heavy drinkers. Br J Addict. 1990;85:1639–1645. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1990.tb01654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Holmes CJ, Jernigan TL, Toga AW. In vivo evidence for post-adolescent brain maturation in frontal and striatal regions. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:859–861. doi: 10.1038/13154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beijsterveldt CEM, van Baal GCM. Twin and family studies of the human electroencephalogram: a review and a meta-analysis. Biol Psychol. 2002;61:111–138. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(02)00055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beijsterveldt CEM, van Baal GCM, Molenaar PCM, Boomsma DI, de Geus EJC. Stability of genetic and environmental influences on P300 amplitude: a longitudinal study in adolescent twins. Behav Genet. 2001;31:533–543. doi: 10.1023/a:1013389226795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viken RJ, Kaprio J, Rose RJ. Personality at ages 16 and 17 and drinking problems at ages 18 and 25: genetic analysis of data from FinnTwin16-25. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2007;10:25–32. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen J, Rinne T, Ilmoniemi RJ, Näätänen R. MEG-compatible multichannel EEG electrode array. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1996;96:568–570. doi: 10.1016/s0013-4694(96)96575-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. J Stud Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright MJ, Hansell NK, Geffen GM, Geffen LB, Smith GA, Martin NG. Genetic influence on the variance in P3 amplitude and latency. Behav Genet. 2001;31:555–565. doi: 10.1023/a:1013393327704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon HH, Iacono WG, Malone SM, McGue M. Using the brain P300 response to identify novel phenotypes reflecting genetic vulnerability for adolescent substance misuse. Addict Behav. 2006;31:1067–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]