Abstract

LIN28B is a homolog of LIN28 which induces pluripotency when expressed in conjunction with OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4 in somatic fibroblasts. LIN28B represses biogenesis of let-7 microRNAs and is implicated in both development and tumorigenesis. Recently, we have determined that LIN28B overexpression occurs in colon tumors. We conducted a comprehensive analysis of Lin28b protein expression in human colon adenocarcinomas. We found that LIN28B overexpression correlates with reduced patient survival and increased probability of tumor recurrence. In order to elucidate tumorigenic functions of LIN28B, we constitutively expressed LIN28B in colon cancer cells and evaluated tumor formation in vivo. Tumors with constitutive Lin28b expression exhibit increased expression of colonic stem cell markers LGR5 and PROM1, mucinous differentiation, and metastasis. Together, our findings point to a function for LIN28B in promoting colon tumor pathogenesis, especially metastasis.

Keywords: LIN28B, LIN28, let-7, colon cancer, differentiation, metastasis

Introduction

LIN28B is a homolog of LIN28 (1), a heterochronic gene initially described in C. elegans as a regulator of developmental timing (2–5). LIN28 induces pluripotency when expressed in somatic fibroblasts in conjunction with OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4 (6). Lin28 and Lin28b each contain a cold shock domain and retroviral-type (CCHC) zinc fingers that confer RNA-binding ability (2, 7) and inhibit biogenesis of tumor-suppressive microRNAs of the let-7 family (8–11).

LIN28 and LIN28B are implicated in multiple developmental processes, largely as a consequence of their ability to repress let-7 biogenesis. In C. elegans, let-7 is critical to the larval fate transition, and vulval specification (12); Lin-28 mutants reiterate larval fates (2). In human embryonic stem cells, relief of let-7 suppression via LIN28 down-regulation occurs during differentiation (13). During neuronal differentiation, LIN28 is also specifically down-regulated, and constitutive expression blocks gliogenesis in favor of neurogenesis (14). LIN28B mutations are associated with delayed onset of puberty in humans (15), which can be modeled via constitutive expression of LIN28 in mice (16). Induction of LIN28 overexpression in transgenic mice expands transit-amplifying cells in the intestinal crypt compartment causing gut pathology and death (16), thus suggesting potential roles for LIN28 and LIN28B in intestinal and colonic development and disease.

LIN28 and LIN28B are implicated in tumorigenesis in different cancers, but LIN28B overexpression in human cancers has been demonstrated more frequently (17). For example, LIN28B is overexpressed in hepatocellular carcinomas (1). In addition, an analysis of LIN28 and LIN28B expression in various cancers pointed to LIN28B as perhaps the more relevant homolog in tumorigenesis (17). This study implicates roles for LIN28B in Wilms’ tumors where the c-myc binding site on LIN28B’s promoter is frequently demethylated, and chronic myeloid leukemia where expression of LIN28B occurs more commonly in blast crisis. Moreover, LIN28B overexpression occurs in non-small cell lung cancer, breast cancer, melanoma, while aberrations in LIN28 expression were not as readily identifiable (17).

LIN28B may be up-regulated as a consequence of APC mutation, which occurs in the vast majority of colon tumors, resulting in sustained β-catenin stabilization and upregulation of the Wnt pathway targets (18, 19). The oncogenic transcription factor c-myc is an established target of the Wnt pathway that functions in part via transcriptional activation of LIN28B (18, 20). Accordingly, increased LIN28B expression in colon tumors may occur as a consequence of elevated c-myc levels and Wnt pathway deregulation (2, 18, 20). Yet, the role of LIN28B in tumorigenesis in vivo remains to be determined.

We examined LIN28B expression in human colon tumors in tissue microarrays and found that LIN28B overexpression correlates with reduced patient survival and increased probability of tumor recurrence. In order to elucidate further roles of LIN28B in colon tumorigenesis, we constitutively expressed LIN28B in colon cancer cell lines and subsequently evaluated tumor promoting properties of LIN28B-expressing cells in xenografted nude athymic mice. Surprisingly, we observed increased differentiation with glandular formation in LIN28B-expressing tumors. However, while smaller than vector-only controls, the LIN28B-expressing tumors have a greater tendency to metastasize. Additionally, we conducted gene expression profile analyses of colon cancer cell lines, primary xenograft tumors, and metastases constitutively expressing LIN28B. We found stem cell-related genes, including the colonic stem cell markers LGR5 and PROM1, to be up-regulated as a function of constitutive LIN28B expression. Taken together, our findings support a role for LIN28B in the progression of colon cancer.

Materials and Methods

Tumor Tissue Microarray Analysis

A uniform cohort of 228 (133 males and 95 females) patients with colon carcinoma (88 in stage 2, and 140 in stage 3) diagnosed between November 1993 and October 2006 was selected. Rectal tumors were excluded. The age of the patients ranged from 35 to 88 years (mean: 66.4 years). The majority of the tumors (156) were located on the left colon; i.e.: 132 sigmoid, 13 splenic flexure, and 11 in the descendent colon, while 72 tumors were located on the right colon; i.e: 26 caecum, 24 ascendent, 14 transverse, and 8 in the hepatic flexure. Seven patients had synchronous tumors. Tumor size varied from 1.6 to 14 cm (mean: 3.8 cm). Six tumors were of grade 1, 212 of grade 2, and 10 of grade 3. Tissue samples were obtained from patients under Institutional Review Board approval. Two cores of normal mucosa and two cores of tumor tissue for each patient were paraffin-embedded in ordered microarrays. Tumor microarrays were sectioned in preparation for immunohistochemical staining. Lin28b staining intensity was scored by a pathologist - 1 was used to signify low Lin28b intensity, 2 for intermediate intensity, and 3 for high. Logrank tests (Mantel–Cox and Breslow) were performed to compare survival and recurrence distributions of intensity groups (1–2 vs 3). Correlation of staining intensity with survival and recurrence was determined via Chi-square analysis; 95% confidence interval calculated for confirmation of statistical significance.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded tissue microarrays and xenograft tumors were incubated at 60° C prior to de-waxing and rehydration. Antigen retrieval was done by placing sections in 10 μM citric acid (pH 6) and microwaving for 15 minutes. Endogenous peroxidases were quenched in 15 ml hydrogen peroxide and 185 ml of water. Tissues were washed with PBS prior to treatment with Avidin D and Biotion using Vectastain (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). Samples were washed again with PBS prior to treatment with Starting Block (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) for 10 minutes. Tissues were incubated in Lin28b (1:200; Cell Signaling, Boston, MA) or GFP (1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) primary antibodies diluted in PBT (10X PBS, 10% BSA, 10% Triton X-100 in ddH2O) at 4° C overnight. Samples were washed with PBS on the following day, incubated in secondary antibody (1:1000), washed and then treated with ABC Peroxidase Staining Kit (Pierce, Rockford IL) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. For detection, a DAB Peroxidase Detection Kit (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) was used and color development was monitored using a light microscope. The development process was terminated removing DAB and rinsing the sections with ddH2O for 1 min prior to counterstaining with hematoxylin.

Generation of constitutive LIN28B-expressing cell lines

DLD-1 and LoVo cells were obtained from ATCC (a recognized vendor) in 2000 and stored in liquid nitrogen prior to resuscitation in 2009 (cell lines were authenticated by ATCC via DNA fingerprinting and cytogenetic analyses). Stable LIN28B expression in DLD-1 and LoVo cells was achieved using MSCV-PIG-LIN28B and empty vector control plasmids (gifts from Dr. Joshua Mendell). We transfected Phoenix A cells with 30ug plasmid DNA, and monitored transfection efficiency via detection of GFP expression by light microscopy prior to virus collection. Viral containing supernatant was collected 48hrs post-transfection, filtered through a 0.45μm membrane, immediately placed in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80° C for later use. DLD-1 and LoVo cells were infected by applying virus-containing media plus polybrene (4 μg/ml) to cells, then subjecting them to centrifugation at 1000g for 90 minutes. Inoculated cells were selected in puromycin, expanded, and subsequently sorted for high GFP intensity and corresponding LIN28B expression.

Xenograft tumors

CrTac:NCr-Foxn1nu nude athymic mice (Taconic, Hudson, NY) were irradiated with 5 Gray 2–3 hours prior to injection of cells. Empty vector and LIN28B-expressing DLD-1 and LoVo cells were trypsinized and washed in PBS and resuspended at a concentration of 2 × 107 cells/ml. 50 μl of cell suspensions were mixed with 50 μl of BD Matrigel™ Basement Membrane Matrix (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) to achieve a volume of 100 μl containing 1 × 106 cells per injection. Cells were injected subcutaneously into the rear flanks of mice sedated with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg. Following injection, mice were monitored periodically and sacrificed after 6 weeks. All mice were cared for in accordance with University Laboratory Animal Resources (ULAR) requirements.

Detection of GFP fluorescence by image analysis

Xenografted nude mice were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) and measured fluorescence intensity using a small animal imaging system (Kodak, Rochester, NY). Net tumor intensity was calculated over a fixed region of interest (ROI) that encompasses the dimensions of the largest tumor. Statistical significance of comparisons between empty vector and LIN28B tumors was determined by applying student’s t-test, where p<0.05 is statistically significant.

Gene expression analysis in xenograft tumors

Mice were euthanized in accordance with ULAR standards prior to excision of xenograft tumors. Extraneous tissues were dissected away and discarded, tumors were then immediately placed into RNAlater (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and maintained on ice until storage at −80° C. Tumor tissue was homogenized mechanically in RNAlater (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and homogenized particulates were collected via centrifugation at 4° C. RNA was isolated from homogenized tissues using a mirVana RNA isolation kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). For detection of mature let-7a and let-7b microRNAs, Taqman® MicroRNA Assay kits (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) were employed to synthesize probe-specific cDNA from 10ng of total RNA per sample. Probe-specific cDNA was amplified using proprietary primers (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, California) and TaqMan® Universal PCR Master Mix, No AmpErase UNG (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). PCR amplifications were performed in triplicate and normalized to levels of endogenous U47. The statistical significance of comparisons between empty vector DLD1 and LoVo versus LIN28B-DLD1 and LIN28B-LoVo cells was evaluated by applying student’s t-test, with p<0.05 considered significant. For detection of mRNA transcripts, cDNA was synthesized from 3 μg isolated RNA per sample using random oligomers and SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Synthesized cDNA was then subjected to gene expression analysis via real-time qPCR using the ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). Transcripts were amplified and detected using specific probes with β-actin serving as an endogenous control (Ambion, Austin, TX). Fold change for each transcript was determined by normalization to empty vector controls.

Microarray analysis

RNA was isolated using a mirVana kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) from empty vector and LIN28B expressing DLD-1 and LoVo colon cancer cell lines, primary xenograft tumors, and LIN28B-expressing mesenteric metastases. Triplicate RNA isolates were submitted to the Penn Microarray Facility. Quality control tests of the total RNA samples were performed using Agilent Bioanalyzer and Nanodrop spectrophotometry. 100ng of total RNA was then converted to first-strand cDNA using reverse transcriptase primed by a poly(T) oligomer that incorporated a synthetic RNA sequence. Second-strand cDNA synthesis was followed by ribo-SPIA (Single Primer Isothermal Amplification, NuGEN Technologies Inc. San Carlo, CA) for linear amplification of each transcript. The resulting cDNA was fragmented, assessed by Bioanalyzer, and biotinylated. cDNA yields were added to Affymetrix hybridization cocktails, heated at 99°C for 2 min and hybridized for 16 h at 45°C to Affymetrix Human Gene 1.0 ST Array GeneChips (Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara CA). The microarrays were then washed at low (6X SSPE) and high (100mM MES, 0.1M NaCl) stringency and stained with streptavidin-phycoerythrin. Fluorescence was amplified by adding biotinylated anti-streptavidin and an additional aliquot of streptavidin-phycoerythrin stain. A confocal scanner was used to collect fluorescence signal after excitation at 570 nm. All protocols were conducted as described in the NuGEN Ovation manual and the Affymetrix GeneChip Expression Analysis Technical Manual.

Bioinformatics Analysis

Three independent biological replicates for each condition were assayed on microarrays. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering by sample was performed to confirm that replicates within each condition grouped with most similarity, and to identify any outlier samples. Significance Analysis of Microarrays (SAM v3.0, www-stat.stanford.edu/~tibs/SAM/) was used to generate lists of statistically significant differentially expressed genes in pairwise comparisons of replicate averages between conditions. Constitutive LIN28B expression in vitro resulted in 13,156 genes with higher RNA abundance, and 15,771 genes with lower RNA abundance when compared to empty vector controls. Candidate genes from the in vitro analysis were filtered by fold-change (threshold = 5 fold) and the resulting gene lists were tested for over-representation. Constitutive LIN28B expression in vivo resulted in 11,242 genes with higher RNA abundance in LIN28B metastases vs. control, and 17,579 genes were lower than in control. Candidate genes were further filtered by fold-change (threshold = 4 fold) and the resulting gene lists were tested for over-representation of Gene Ontology annotation categories using the DAVID Bioinformatics Resources (david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov).

To stratify patients with colon cancer according to the similarity of their gene expression patterns to LIN28B-specific gene expression signature, we adopted a previously developed model (21–23). Briefly, we first identified genes whose expression was significantly associated with expression of LIN28B from cell culture. A highly stringent cut-off (P < 0.001) was applied to avoid inclusion of potential false-positive genes during training of prediction models. Expression data from selected genes (704 genes) were then combined to form a classifier according to compound covariate predictor (CCP) algorithm and the robustness of the classifier was estimated by misclassification rate determined during the leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) in the training set (data from cell culture). When applied to gene expression data from the patients (n = 290, GSE14333), prognostic significance was estimated by Kaplan-Meier plots and log-rank tests between 2 predicted subgroups of patients. After LOOCV, sensitivity and specificity of prediction models were estimated by the fraction of samples correctly predicted.

Results

Aberrant LIN28B expression correlates with reduced patient survival

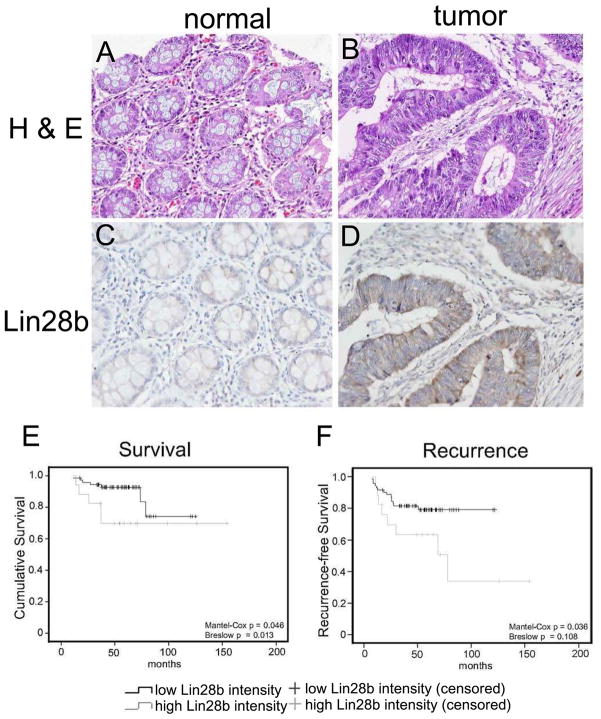

In order to determine potential roles of LIN28B in colon cancer pathogenesis, we examined LIN28B expression in human colon tumors and matched adjacent normal mucosa. Tumor and adjacent normal tissue samples resected from patients receiving adjuvant 5-fluorouracil were paraffin-embedded in duplicate on to tissue microarrays. Immunohistochemistry was perfomed for Lin28b and staining intensity was scored by a pathologist blinded to clinical information. Lin28b staining in normal colon is faint; by contrast, intense Lin28b staining was observed in colon tumors (Figure 1a–d; Supplementary Figure 1). Colon tumor samples were further analyzed via logrank tests (Mantel–Cox and Breslow) comparing overall survival and recurrence distributions of intensity groups. This revealed a correlation between low intensity Lin28b staining in stage I and II colon tumors with higher patient survival (Mantel-Cox p value = 0.046; Breslow, p value = 0.013) and lower probability of tumor recurrence (Mantel-Cox p value = 0.036; Breslow p value = 0.108) (Figure 1e–f).

Figure 1. LIN28B overexpression in colon carcinomas correlates with reduced survival and increased probability of tumor recurrence.

(A–D) Representative H&E and IHC for Lin28b in matched normal mucosa and colon carcinomas in tissue microarrays. Lin28b staining is intense in a subset of colon tumors. (E) Lin28b expression and patient survival. High Lin28b staining intensity in stage I and II colon cancers correlates with reduced patient survival. (F) Lin28b and tumor recurrence. High Lin28b staining intensity in stage I and II tumors correlates with increased probability of tumor recurrence.

LIN28B tumors exhibit reduced size and glandular differentiation

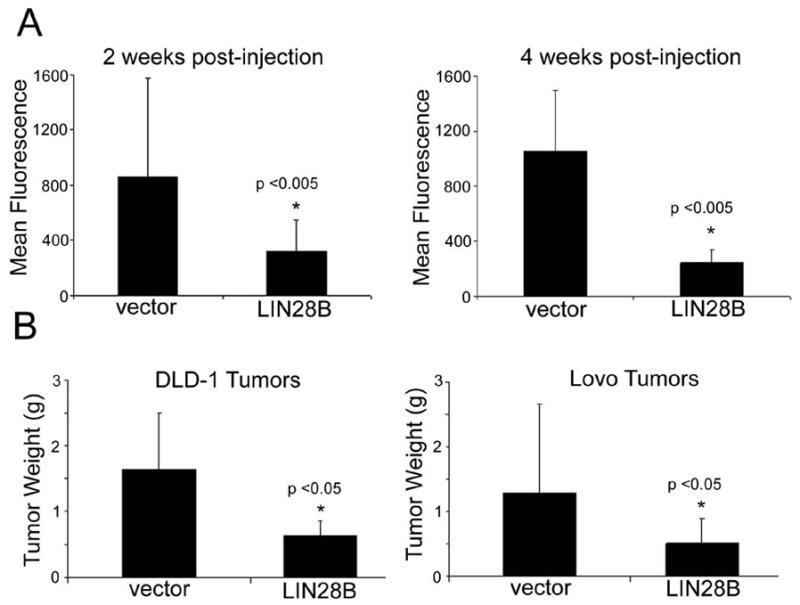

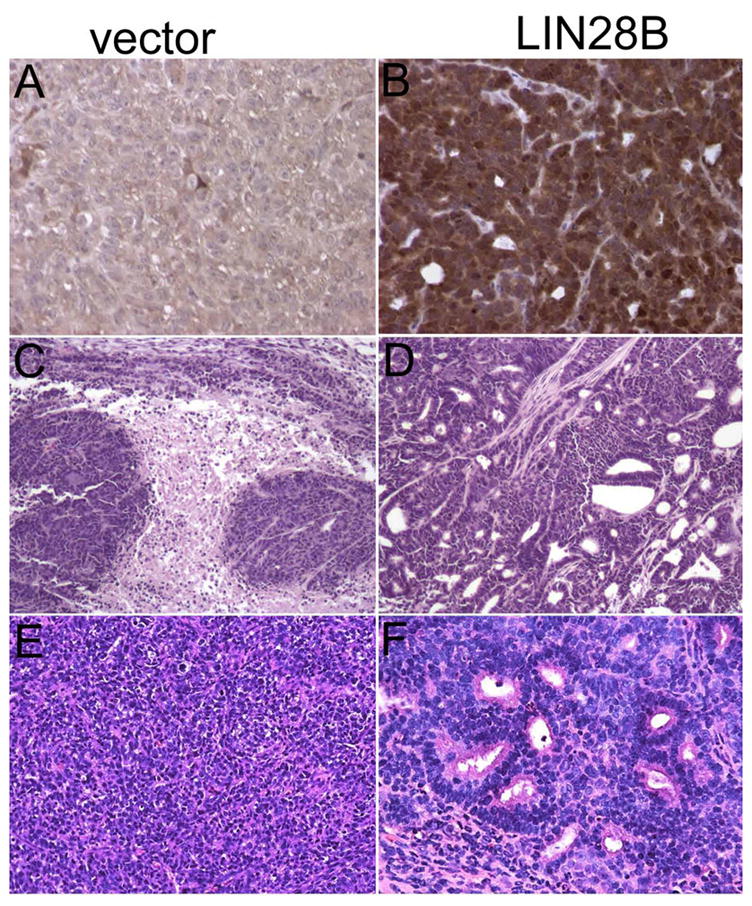

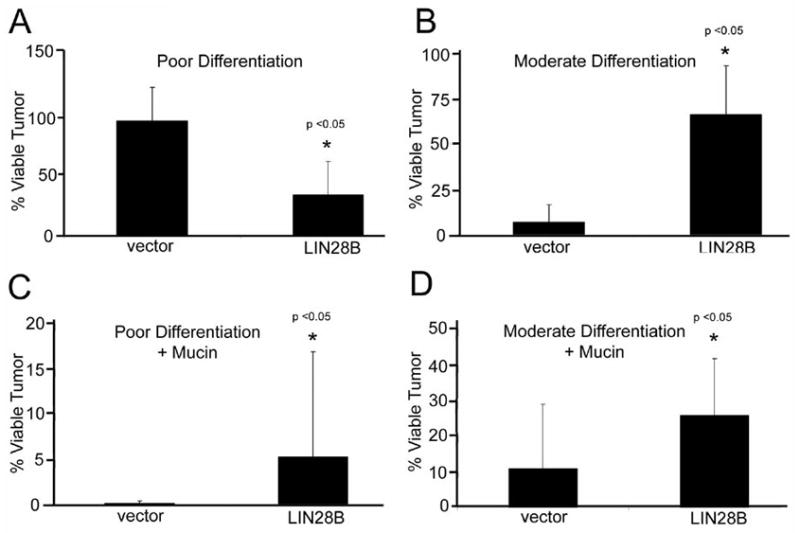

Given that high Lin28b levels in colon tumors correlate with increased probability of tumor recurrence in patients, we hypothesized a biological role for LIN28B in colon cancer pathogenesis. In order to elucidate this further, we constitutively expressed LIN28B in DLD-1 and LoVo colon cancer cells. We then established xenograft tumors by injecting 1 × 106 cells subcutaneously into the rear flanks of nude athymic mice. We initially monitored tumor development via detection of GFP fluorescence (expressed from the MSCV-PIG retroviral vector) in a total of 83 xengografted mice: 41 empty vector controls and 42 LIN28B-overexpressing tumors. At two and four weeks post-injection, we found that LIN28B tumors emitted less fluorescence (Figure 2a–b). This observation corresponds to a smaller tumor mass observed in LIN28B-expressing tumors (Figure 2c–d). We next confirmed LIN28B overexpression in tumors via immunohistochemistry (Figure 3a–b). In addition, mature let-7 microRNAs, which are repressed by Lin28b, are reduced in the presence of constitutive LIN28B expression in xenograft tumors (Supplementary Figure 2). Surprisingly, LIN28B tumors exhibited increased areas of moderate differentiation, increased glandular formation, and increased mucin production, in contrast to empty vectors tumors that are poorly differentiated and rarely exhibit mucinous, gland-like structures (Figure 3c–f). Viable tumor areas were scored for poor and moderate differentiation, as well as mucin production revealing statistically significant differences between empty-vector and LIN28B-expressing xenograft tumors (Figure 4). However, Ki-67 and caspase-3 staining did not reveal significant differences (data not shown).

Figure 2. LIN28B tumors have reduced size.

(A) LIN28B tumors emit less fluorescence than controls. GFP intensity of xenograft tumors was assessed at bi-weekly intervals; at each interval, fluorescence intensity for LIN28B tumors was less than controls. Representative 2 and 4 week analyses of a single cohort injected with vector-LoVo or LIN28B-LoVo cells. (B) LIN28B tumors are smaller than controls. Tumor weights 6 weeks post-injection and extraction.

Figure 3. Histopathological examination of empty vector and LIN28B-expressing primary tumors.

(A and B) Confirmation of LIN28B overexpression in tumors. Immunohistochemical detection of Lin28b in vector-LoVo and LIN28B-LoVo xenografts; representative of 83 tumors tested (200× magnification). (C–F) H&E staining of xenograft tumors. Empty vector tumors which exhibit broad areas of necrosis (C), and poor differentiation (E) while LIN28B-expressing tumors exhibit fewer necrotic areas (D), moderate differentiation, glandular formation, and increased mucin production (F); 100× magnification in C and D, 200× in E and F.

Figure 4. Differentiation and mucin production in LIN28B tumors.

(A) Poor differentiation in xenograft tumors. Area exhibiting poor differentiation scored as a percentage of viable tumors. LIN28B-expressing tumors exhibit fewer areas of poor differentiation. (B) Moderate differentiation in xenograft tumors. Area exhibiting moderate differentiation scored as a percentage of viable tumors. Moderate differentiation is increased in LIN28B-expressing tumors. (C) Mucin positivity in poorly differentiated tumor areas. Mucin was detected via mucicarmine staining. Mucin positivity in poorly differentiated area scored as a percentage of viable tumor. (D) Mucin positivity in moderately differentiated tumor areas. Mucin positivity in poorly differentiated scored as a percentage of viable tumor. Differentiation is increased in LIN28B-expressing tumors. Mucin production is increased in LIN28B-expressing tumors.

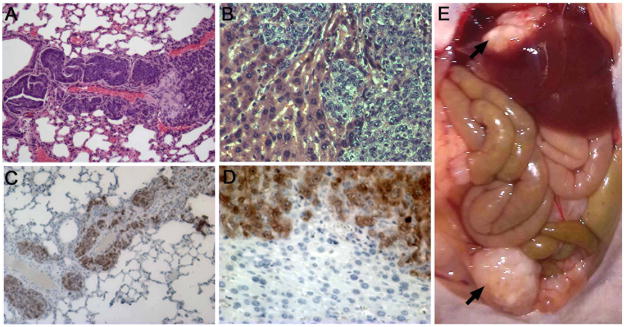

LIN28B tumors metastasize to multiple organs

During necropsy, we observed mesenteric and liver metastases in mice xenografted with LIN28B-expressing cells upon gross examination (Figure 5e), which prompted extensive examination of internal organs. While we did not observe metastases in any mice in the empty vector control group, we did note liver, lung, perisplenic adipose, lymph node, and mesenteric metastases in mice bearing tumors with constitutive LIN28B expression (Figure 5a–b). We confirmed that these metastases were derived from xenografted cells via immunohistochemical GFP detection, which is unique to xenografted cells (Figure 5c–d). Overall, we identified metastases in approximately 17% of mice xenografted with LIN28B-expressing cells (7 of 42). Thus, constitutive LIN28B expression in colon cancer cells confers metastatic ability in at least a subset of tumors (Fisher’s exact one-tailed probability = 0.0065).

Figure 5. A subset of LIN28B-expressing primary tumors metastasize.

(A) Lung metastasis from a LIN28B-DLD1 subcutaneous tumor. H&E staining. (B) Liver metastasis from a LIN28B-LoVo subcutaneous tumor. Hematoxylin and eosin staining; note invasion of metastasis into normal liver (C and D) Metastases are GFP-positive. Immunohistochemistry for GFP expressed from MSCV-PIG retroviral vector confirms that these tissue originated from xenograft injections. (E) Metastases visible upon gross examination. Arrows indicate liver and mesenteric metastases from LIN28B-LoVo tumors (magnification = 100× in panels A and B; 200× in panels C and D).

Stem-cell like gene expression profile induced by constitutive LIN28B expression

We next performed microarray analysis on total RNA isolated from empty vector and LIN28B-expressing cell lines and primary tumors, as well as LIN28B-LoVo metastases. We identified more than 184 transcripts (164 up-regulated; 20 down-regulated) that are more than 5-fold changed with constitutive LIN28B expression in vitro (accession numbers GSM646687- GSM646692). Some transcripts up-regulated by LIN28B have reported roles in stem cell biology including the hematopoietic stem cell marker, KIT (also called CD117 or c-KIT), as well as the intestinal stem cell markers LGR5 (leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein coupled receptor 5) and PROM1 (prominin 1) (Table I). Of note, LGR5 is a transcriptional target of canonical Wnt signaling (24, 25). Additional Wnt targets including DKK1 (Dickkopf-related protein 1) (26, 27) and CCND2 (cyclin D2) (28, 29) are up-regulated by LIN28B overexpression as well (Table I). These results were verified by RT-qPCR (data not shown).

Table I. Selected Transcripts up-regulated by Lin28b.

| Transcripts up-regulated by constitutive Lin28b expressionin vitroa | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Fold Change* (Vector vs. LIN28B) |

| LGR5 | leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 5 | 7.2 |

| PROM1 | prominin 1 | 22.6 |

| KIT | v-kit Hardy-Zuckerman 4 feline sarcoma viral oncogene homolog | 36.6 |

| HMGA2 | high mobility group AT-hook 2 | 2.6 |

| IGF2BP1 | insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein 1 | 9.4 |

| CCND2 | cyclin D2 | 6.6 |

| DKK1 | dickkopf homolog 1 | 37.1 |

| Transcripts up-regulated in Lin28b-expressing metastasesin vivob | ||

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Fold Change* (Tumor vs. Met) |

| CHI3L1 | chitinase 3-like 1 | 4.4 |

| KLK6 | kallikrein-related peptidase 6 | 4.3 |

| TNS4 | tensin 4 | 4.6 |

selected transcripts up-regulated by constitutive LIN28B expression in colon cancer cells in vitro.

selected transcripts up-regulated in metastases derived from primary xenograft tumors constitutively expressing LIN28B in vivo.

Fold changes indicated are the mean of three experimental replicates.

In addition, we identified more than 22 genes that are more than 4-fold up-regulated, and 57 genes that are more than 4-fold down-regulated by constitutive LIN28B expression in vivo (accession numbers GSM646700- GSM646708). Many genes that are up-regulated with constitutive LIN28B expression in vitro are also increased by constitutive LIN28B expression in vivo, including the stem cell markers LGR5 (24) and PROM1 (30), and the let-7 targets HMGA2 (High-mobility group AT-hook 2) (31, 32) and IGF2BP1 (Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 1) (33); these results were verified by RT-qPCR analysis (data not shown). Overall, the expression profile of empty vector tumors varies dramatically from that of LIN28B-expressing primary tumors (Supplementary Figure 3a). Notably, the expression profile of LIN28B metastases also differs from that of LIN28B primary xenograft tumors (Supplementary Figure 3a). Some genes specifically modulated in LIN28B metastases versus LIN28B primary tumors have described roles in migration, invasion, and metastasis, such as TNS4 (Tensin 4), CHI3L1 (Chitinase 3-like-1), and KLK6 (Kallikrein 6) (Table I).

Since we observed metastases with constitutive LIN28B expression in cells, we sought to determine whether the gene expression profile induced by LIN28B resembled that of naturally occurring metastatic human colon tumors. Therefore, we cross-compared the LIN28B-specific gene expression signature with that of patients with colon adenocarcinomas. For this analysis, we used publicly available gene expression data from 290 patients with colon adenocarcinomas (37). When patients were stratified according to the LIN28B-specific gene expression signature (Supplementary Figure 3b), disease-free survival of patients with tumors bearing gene expression patterns similar to the LIN28B signature is significantly shorter (P = 0.02, by log-rank test, Supplementary Figure 3b), indicating that LIN28B in colon cancer may influence clinical outcome in patients with colon cancer by promoting early metastasis. Specificity and sensitivity for correctly predicting LIN28B overexpression during LOOCV were both 1.0.

Discussion

We found that increased Lin28b staining intensity in non-metastatic colon tumors correlates with reduced overall survival and increased probability of tumor recurrence in patients receiving adjuvant 5-fluorouracil. We then examined tumor-promoting properties of LIN28B-expressing colon cancer cells via tumorigenesis studies in nude athymic mice. Primary xenograft tumors that constitutively express LIN28B display decreased size and increased differentiation characterized by glandular formation relative to empty vector controls. Yet, LIN28B-expressing xenograft tumors are capable of metastasis, which is not observed with empty vector xenograft tumors do not.

We have demonstrated increased LIN28B expression in primary colon tumors, which may be the result of increased LIN28B transcriptional activity mediated by c-myc. Since c-myc is a transcriptional target of canonical Wnt signaling, it is possible that LIN28B is up-regulated in colon tumors as a consequence of APC mutation (or other changes that deregulate Wnt signaling), which occurs in the majority of sporadic colon tumors. The ability of c-myc to transactivate LIN28 has not been described and may account for differential properties of LIN28 and LIN28B in colon cancer. However, it is important to note that distinct functions have not been described for either homolog to date, and it is possible that the two are completely redundant.

Although our findings reveal potential roles for LIN28B in colon cancer metastasis, it is surprising for genes that promote tumorigenesis and/or metastasis to simultaneously enhance differentiation. Thus, our finding that primary tumors constitutively expressing LIN28B are smaller and more differentiated than their empty vector counterparts is intriguing. Given that constitutive LIN28 expression in undifferentiated cells blocks gliogenesis in favor of neurogenesis (14), it is possible that LIN28B overexpression in colonic epithelial cells results in restriction of cell fate as observed previously in neuronal cells. Similar phenotypes have previously been described in the intestine. For example, loss of the Math1 (also called Atoh1) transcription factor leads to depletionof goblet, enteroendocrine, and Paneth cells, while permittingenterocyte differentiation in the intestinal epithelium (38).

Furthermore, LIN28B up-regulates the colonic epithetlial stem cell markers LGR5 and PROM1. In the intestine, expression of the cell surface protein PROM1 is restricted to the crypt and adjacent epithelial cells (30), while expression of the orphan receptor LGR5 occurs exclusively in cycling columnar cells within the crypt base (24). Since LGR5 and PROM1 mark intestinal and colonic epithelial stem cells, up-regulation of these factors by LIN28B suggests possible roles for LIN28B in intestinal stem cells.

Our finding that high Lin28b staining intensity in primary human colon tumors correlates with reduced patient survival and increased probability of tumor recurrence is especially intriguing given that LIN28B-expressing xenograft tumors metastasize in the context of a more differentiated primary tumor. While low tumor grade usually corresponds to early stage and better prognosis, metastasis and poor prognosis is observed in a subset of low-grade tumors (39, 40). Given that we find both differentiation and metastasis with constitutive LIN28B expression in primary tumors, LIN28B overexpression may mark low grade tumors with poor prognostic potential. Thus, LIN28B may serve as a potential diagnostic marker that may prove to be an invaluable tool in colon cancer where early diagnosis is critical to survival.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by R01-DK056645 (AR, CK), The Hansen Foundation, National Colon Cancer Research Alliance (EIF), and grants from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (SAF2010-19273), Asociación Española contra el Cáncer (Fundación Científica y Junta de Barcelona), and Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (2009 SGR 849). Catrina King is a Pfizer Animal Health scholarship recipient and a student of the University of Pennsylvania combined VMD/PhD program. We thank Dr. Joshua Mendell for gifts of LIN28B expression vectors, as well as Ben Rhoades and Louise Wang for technical assistance. We also acknowledge help from the NIH/NIDDK P30-DK050306 Center for Molecular Studies in Digestive and Liver Diseases and its Morphology, Molecular Biology and Cell Culture Core Facilities. We thank the Penn Microarray Facility, including Drs. John Tobias and Don Baldwin, Dr. Daqing Li of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology/Head & Neck Surgery for use of the Kodak small animal imaging system, and Colleen Bressinger for assistance with biostatistical analysis.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Guo Y, Chen Y, Ito H, Watanabe A, Ge X, Kodama T, et al. Identification and characterization of lin-28 homolog B (LIN28B) in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Gene. 2006;384:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moss EG, Lee RC, Ambros V. The cold shock domain protein LIN-28 controls developmental timing in C. elegans and is regulated by the lin-4 RNA. Cell. 1997;88:637–46. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81906-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Euling S, Ambros V. Heterochronic genes control cell cycle progress and developmental competence of C. elegans vulva precursor cells. Cell. 1996;84:667–76. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Euling S, Ambros V. Reversal of cell fate determination in Caenorhabditis elegans vulval development. Development. 1996;122:2507–15. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.8.2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ambros V, Horvitz HR. Heterochronic mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1984;226:409–16. doi: 10.1126/science.6494891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–20. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moss EG, Tang L. Conservation of the heterochronic regulator Lin-28, its developmental expression and microRNA complementary sites. Dev Biol. 2003;258:432–42. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hagan JP, Piskounova E, Gregory RI. Lin28 recruits the TUTase Zcchc11 to inhibit let-7 maturation in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1021–5. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heo I, Joo C, Cho J, Ha M, Han J, Kim VN. Lin28 mediates the terminal uridylation of let-7 precursor MicroRNA. Mol Cell. 2008;32:276–84. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lehrbach NJ, Armisen J, Lightfoot HL, Murfitt KJ, Bugaut A, Balasubramanian S, et al. LIN-28 and the poly(U) polymerase PUP-2 regulate let-7 microRNA processing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1016–20. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rybak A, Fuchs H, Smirnova L, Brandt C, Pohl EE, Nitsch R, et al. A feedback loop comprising lin-28 and let-7 controls pre-let-7 maturation during neural stem-cell commitment. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:987–93. doi: 10.1038/ncb1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson SM, Grosshans H, Shingara J, Byrom M, Jarvis R, Cheng A, et al. RAS is regulated by the let-7 microRNA family. Cell. 2005;120:635–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Viswanathan SR, Daley GQ, Gregory RI. Selective blockade of microRNA processing by Lin28. Science. 2008;320:97–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1154040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balzer E, Heine C, Jiang Q, Lee VM, Moss EG. LIN28 alters cell fate succession and acts independently of the let-7 microRNA during neurogliogenesis in vitro. Development. 2010;137:891–900. doi: 10.1242/dev.042895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tommiska J, Wehkalampi K, Vaaralahti K, Laitinen EM, Raivio T, Dunkel L. LIN28B in constitutional delay of growth and puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;95:3063–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu H, Shah S, Shyh-Chang N, Shinoda G, Einhorn WS, Viswanathan SR, et al. Lin28a transgenic mice manifest size and puberty phenotypes identified in human genetic association studies. Nat Genet. 42:626–30. doi: 10.1038/ng.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Viswanathan SR, Powers JT, Einhorn W, Hoshida Y, Ng TL, Toffanin S, et al. Lin28 promotes transformation and is associated with advanced human malignancies. Nat Genet. 2009;41:843–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He TC, Sparks AB, Rago C, Hermeking H, Zawel L, da Costa LT, et al. Identification of c-MYC as a target of the APC pathway. Science. 1998;281:1509–12. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powell SM, Zilz N, Beazer-Barclay Y, Bryan TM, Hamilton SR, Thibodeau SN, et al. APC mutations occur early during colorectal tumorigenesis. Nature. 1992;359:235–7. doi: 10.1038/359235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang TC, Zeitels LR, Hwang HW, Chivukula RR, Wentzel EA, Dews M, et al. Lin-28B transactivation is necessary for Myc-mediated let-7 repression and proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3384–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808300106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JS, Heo J, Libbrecht L, Chu IS, Kaposi-Novak P, Calvisi DF, et al. A novel prognostic subtype of human hepatocellular carcinoma derived from hepatic progenitor cells. Nat Med. 2006;12:410–6. doi: 10.1038/nm1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee JS, Chu IS, Mikaelyan A, Calvisi DF, Heo J, Reddy JK, et al. Application of comparative functional genomics to identify best-fit mouse models to study human cancer. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1306–11. doi: 10.1038/ng1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JS, Chu IS, Heo J, Calvisi DF, Sun Z, Roskams T, et al. Classification and prediction of survival in hepatocellular carcinoma by gene expression profiling. Hepatology. 2004;40:667–76. doi: 10.1002/hep.20375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, Kujala P, van den Born M, Cozijnsen M, et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van der Flier LG, Sabates-Bellver J, Oving I, Haegebarth A, De Palo M, Anti M, et al. The Intestinal Wnt/TCF Signature. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:628–32. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niida A, Hiroko T, Kasai M, Furukawa Y, Nakamura Y, Suzuki Y, et al. DKK1, a negative regulator of Wnt signaling, is a target of the beta-catenin/TCF pathway. Oncogene. 2004;23:8520–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chamorro MN, Schwartz DR, Vonica A, Brivanlou AH, Cho KR, Varmus HE. FGF-20 and DKK1 are transcriptional targets of beta-catenin and FGF-20 is implicated in cancer and development. EMBO J. 2005;24:73–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shtutman M, Zhurinsky J, Simcha I, Albanese C, D’Amico M, Pestell R, et al. The cyclin D1 gene is a target of the beta-catenin/LEF-1 pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5522–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tetsu O, McCormick F. Beta-catenin regulates expression of cyclin D1 in colon carcinoma cells. Nature. 1999;398:422–6. doi: 10.1038/18884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snippert HJ, van Es JH, van den Born M, Begthel H, Stange DE, Barker N, et al. Prominin-1/CD133 marks stem cells and early progenitors in mouse small intestine. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2187–94. e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayr C, Hemann MT, Bartel DP. Disrupting the pairing between let-7 and Hmga2 enhances oncogenic transformation. Science. 2007;315:1576–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1137999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee YS, Dutta A. The tumor suppressor microRNA let-7 represses the HMGA2 oncogene. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1025–30. doi: 10.1101/gad.1540407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyerinas B, Park SM, Shomron N, Hedegaard MM, Vinther J, Andersen JS, et al. Identification of let-7-regulated oncofetal genes. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2587–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghosh MC, Grass L, Soosaipillai A, Sotiropoulou G, Diamandis EP. Human kallikrein 6 degrades extracellular matrix proteins and may enhance the metastatic potential of tumour cells. Tumour Biol. 2004;25:193–9. doi: 10.1159/000081102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bockholt SM, Burridge K. Cell spreading on extracellular matrix proteins induces tyrosine phosphorylation of tensin. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:14565–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mizoguchi E. Chitinase 3-like-1 exacerbates intestinal inflammation by enhancing bacterial adhesion and invasion in colonic epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:398–411. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jorissen RN, Gibbs P, Christie M, Prakash S, Lipton L, Desai J, et al. Metastasis-Associated Gene Expression Changes Predict Poor Outcomes in Patients with Dukes Stage B and C Colorectal Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7642–51. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang Q, Bermingham NA, Finegold MJ, Zoghbi HY. Requirement of Math1 for secretory cell lineage commitment in the mouse intestine. Science. 2001;294:2155–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1065718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eschrich S, Yang I, Bloom G, Kwong KY, Boulware D, Cantor A, et al. Molecular staging for survival prediction of colorectal cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3526–35. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mesker WE, Liefers GJ, Junggeburt JM, van Pelt GW, Alberici P, Kuppen PJ, et al. Presence of a high amount of stroma and downregulation of SMAD4 predict for worse survival for stage I–II colon cancer patients. Cell Oncol. 2009;31:169–78. doi: 10.3233/CLO-2009-0478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.